Whole-Brain Imaging for Neural Pathways: Techniques, Applications, and Future Directions in Neuroscience Research

This article provides a comprehensive overview of current whole-brain imaging techniques for mapping neural pathways, addressing the critical needs of researchers and drug development professionals.

Whole-Brain Imaging for Neural Pathways: Techniques, Applications, and Future Directions in Neuroscience Research

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of current whole-brain imaging techniques for mapping neural pathways, addressing the critical needs of researchers and drug development professionals. It explores foundational principles of brain connectivity, details cutting-edge methodological approaches from microscopy to clinical imaging, and offers practical insights for troubleshooting and optimization. By critically comparing the validation metrics and comparative advantages of technologies like ComSLI, CLARITY, DTI, and fMRI, this resource serves as an essential guide for selecting appropriate imaging strategies in both basic research and clinical trial contexts, ultimately supporting more effective neuroscience investigation and therapeutic development.

Understanding Brain Connectivity: Fundamental Principles and Exploration Goals

The BRAIN Initiative's Vision for Comprehensive Neural Circuit Mapping

The Brain Research Through Advancing Innovative Neurotechnologies (BRAIN) Initiative was launched in 2014 as a large-scale, collaborative effort to revolutionize our understanding of the mammalian brain. Its core philosophy is to understand the brain as a complex system that gives rise to the diversity of functions allowing interaction with and adaptation to our environments, which is necessary to promote brain health and treat neurological disorders [1]. A primary focus has been the creation of a comprehensive functional neuroscience ecosystem, sometimes referred to as the 'BRAIN Circuits Program,' which aims to decipher the dynamic neural circuits underlying behavior and cognition [1].

A cornerstone of this vision is the development of technologies for large-scale and whole-brain optical imaging of neuronal activity. The mission is to capture and manipulate the dynamics of large neuronal populations at high speed and high resolution over large brain areas, which is essential for decoding how information is represented and processed by neural circuitry [2]. This involves mapping the brain across multiple scales—from individual synapses to entire circuits—to ultimately construct a detailed blueprint of brain connectivity and function [3] [4].

Core Imaging Technologies for Circuit Mapping

Whole-Brain Optical Imaging at the Mesoscopic Level

Optical imaging provides a powerful tool for brain mapping at the mesoscopic level, offering submicron lateral resolution that can resolve the structure of cells, axons, and dendrites [4]. A key challenge is that classical optical methods like confocal and two-photon microscopy have limited imaging depth. Whole-brain optical imaging overcomes this through two primary technical routes [4]:

- Tissue Clearing-Based Techniques: These methods render biological samples transparent by using refractive index matching to eliminate scattering. They can be categorized as:

- Hydrophobic methods: Use organic solvents for fast and complete transparency (e.g., DISCO, iDISCO, uDISCO, vDISCO).

- Hydrophilic methods: Use water-soluble reagents for better biocompatibility (e.g., SeeDB, CUBIC).

- Hydrogel-based methods: Secure biomolecules in situ through crosslinking (e.g., CLARITY, PACT/PARS).

- Histological Sectioning-Based Techniques: These methods involve physically sectioning the brain into thin slices, which are then imaged and computationally reconstructed into a 3D volume.

Emerging Imaging Modalities and Applications

Ca2+ imaging techniques, using genetically encoded indicators like GCaMP, allow for high-speed optical recording of neuronal activity, enabling researchers to observe the dynamics of functional brain networks [2]. Other advanced modalities include light-sheet microscopy for whole-brain functional imaging at cellular resolution, and multifocus microscopy for high-speed volumetric imaging [2]. These technologies are being applied not only in rodent models but also in non-human primates, which are essential for understanding complex cognitive functions and brain diseases. For instance, the Japan Brain/MINDS project uses marmosets, while the China Brain Science Project focuses on macaques [4].

Key Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Mesoscale Connectomic Mapping of a Mouse Brain

This protocol outlines the steps for generating a comprehensive structural and functional map of a defined brain region, based on the groundbreaking MICrONS project [3].

1. Animal Preparation and In Vivo Functional Imaging:

- Surgical Procedure: Under deep anesthesia, perform a craniotomy over the target brain region (e.g., visual cortex).

- Two-Photon Calcium Imaging: Use a two-photon microscope to record neural activity from the target region while the animal is presented with visual stimuli (e.g., movies, YouTube clips). This establishes a functional map.

- Perfusion and Fixation: Transcardially perfuse the animal with a fixative (e.g., paraformaldehyde) to preserve the brain tissue.

2. Tissue Processing and Electron Microscopy:

- Embedding and Sectioning: Embed the fixed brain region in resin. Using an ultra-microtome, serially section the tissue block into ultra-thin slices (approximately 25,000 slices, each 1/400th the width of a human hair).

- Electron Microscopy Imaging: Acquire high-resolution images of every section using an array of automated electron microscopes.

3. Computational Reconstruction and Analysis:

- Image Alignment and 3D Volume Reconstruction: Use automated computational pipelines and machine learning algorithms to align the serial EM images and reconstruct a continuous 3D volume.

- Automated Segmentation and Tracing: Employ artificial intelligence (AI) to identify and trace individual neurons, axons, dendrites, and synapses within the 3D volume.

- Circuit Analysis: Analyze the reconstructed connectome to identify connection rules, cell types, and network motifs. Integrate the structural data with the previously acquired functional imaging data to link structure with function.

Protocol 2: Whole-Brain Immunohistochemistry and Imaging with Tissue Clearing

This protocol details the use of tissue clearing to image an entire mouse brain without physical sectioning, enabling brain-wide quantification of cells and circuits [4].

1. Perfusion, Fixation, and Brain Extraction:

- Deeply anesthetize the mouse and perform transcardial perfusion first with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) followed by 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA).

- Carefully extract the whole brain and post-fix in 4% PFA for 24 hours at 4°C.

2. Tissue Clearing and Immunostaining (Using Hydrogel-Based CLARITY):

- Hydrogel Embedding: Incubate the brain in a solution of acrylamide/bis-acrylamide, formaldehyde, and thermal initiator to form a hydrogel-monomer mix. Polymerize at 37°C for 3 hours to create a hydrogel-tissue hybrid.

- Lipid Extraction (Electrophoresis): Place the hydrogel-embedded brain in a clearing chamber filled with SDS-based clearing solution (200mM boric acid, 4% SDS, pH 8.5). Apply an electrical field (∼30-40V) for 7-10 days to actively remove lipids.

- Refractive Index Matching: After clearing and washing, incubate the sample in a refractive index matching solution (e.g., FocusClear or 88% Histodenz) for 2-3 days until the tissue becomes transparent.

- Immunostaining (Optional): For labeling specific antigens, the cleared brain can be incubated with primary antibodies for 5-7 days, followed by secondary antibodies for another 5-7 days, with constant shaking.

3. Light-Sheet Microscopy and Data Analysis:

- Mounting: Mount the cleared brain in the imaging chamber filled with refractive index matching solution.

- Imaging: Use a light-sheet microscope to acquire tiled Z-stack images of the entire brain. The use of dual light sheets and orthogonal detection is recommended for improved resolution and speed.

- Data Processing: Stitch the acquired tiles, and use computational tools for cell counting, tracing of neuronal projections, and registration to a standard brain atlas.

Quantitative Data and Scaling

The data generated by BRAIN Initiative-funded projects is massive and requires careful consideration of scale and resolution. The table below summarizes key quantitative benchmarks for neural circuit mapping projects.

Table 1: Quantitative Benchmarks for Neural Circuit Mapping

| Parameter | Mouse Brain (MICrONS Project) | Mouse Brain (Whole) | Marmoset Brain | Macaque Brain |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sample Volume Mapped | 1 mm³ (visual cortex) | ~420 mm³ [4] | ~7,780 mm³ [4] | ~87,350 mm³ [4] |

| Neuron Count | 84,000 neurons [3] | ~70 million [4] | ~630 million [4] | ~6.37 billion [4] |

| Synapse Count | ~500 million [3] | ~10s to 100s of billions (est.) | ~100s of billions to trillions (est.) | ~1,000s of billions (est.) |

| Neuronal Wire Length | ~5.4 kilometers [3] | ~100s of kilometers (est.) | ~1,000s of kilometers (est.) | ~10,000s of kilometers (est.) |

| Data Volume | 1.6 Petabytes [3] | ~Exabyte scale (est.) | ~10s of Exabytes (est.) | ~100s of Exabytes (est.) |

Table 2: Recommended Imaging Parameters for Different Research Goals [4]

| Research Goal | Recommended Voxel Size (XYZ) | Estimated Data for Mouse Brain |

|---|---|---|

| Cell Body Counting | (1.0 µm)³ | ~1 TB |

| Dendritic Arbor Mapping | (0.5 µm)³ | ~10 TB |

| Axonal Fiber Tracing | (0.3 x 0.3 x 1.0) µm | ~5 TB |

| Complete Connectome (EM) | (4 x 4 x 40) nm | >1 PB |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Successful execution of neural circuit mapping experiments relies on a suite of specialized reagents and tools.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Tools for Neural Circuit Mapping

| Reagent/Tool | Function/Description | Example Use Cases |

|---|---|---|

| GCaMP Calcium Indicators | Genetically encoded fluorescent sensors that change intensity upon neuronal calcium influx, a proxy for action potentials. | In vivo functional imaging of neuronal population dynamics in behaving animals [2]. |

| Adeno-Associated Virus (AAV) Tracers | Viral vectors for delivering genetic material (e.g., fluorescent proteins, opsins) to specific neuron populations. Used for anterograde and retrograde tracing. | Mapping input and output connections of specific brain regions (e.g., rAAV2-retro for retrograde labeling) [5]. |

| Monosynaptic Rabies Virus System | A modified rabies virus used for retrograde tracing that only infects neurons presynaptic to a starter population, allowing single-synapse resolution input mapping. | Defining the complete monosynaptic input connectome to a targeted cell type [5]. |

| CLARITY Reagents | A hydrogel-based tissue clearing method. Reagents include acrylamide, formaldehyde, and SDS for lipid removal. | Creating a transparent, macromolecule-preserved whole brain for deep-tissue immunolabeling and imaging [4]. |

| CUBIC Reagents | A hydrophilic tissue clearing method using aminoalcohols (e.g., Quadrol) that delipidate and decolorize tissue while retaining fluorescent signals. | Whole-body and whole-brain clearing for high-throughput phenotyping and cell census studies [4]. |

| Optogenetic Actuators (e.g., Channelrhodopsin) | Light-sensitive ion channels (e.g., Channelrhodopsin-2) that can be expressed in specific neurons to control their activity with millisecond precision using light. | Causally testing the function of specific neural circuits in behavior [5]. |

| Chemogenetic Actuators (e.g., DREADDs) | Designer Receptors Exclusively Activated by Designer Drugs; engineered GPCRs that modulate neuronal activity upon application of an inert ligand (e.g., CNO). | Long-term, non-invasive manipulation of specific neural circuits for behavioral studies and therapeutic exploration [5]. |

Impact and Future Directions in Neurotherapy

The structural and functional insights gained from BRAIN Initiative research are directly informing the development of novel neurotherapeutic strategies. By understanding the "blueprint" of healthy neural circuits, researchers can identify how specific circuits are disrupted in disease and develop targeted interventions [5].

Key advancements include:

- Precision Neuromodulation: Techniques like Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation (TMS) are being refined to target specific dysfunctional circuits, such as the ventromedial prefrontal cortex (VMPFC)-amygdala circuit in substance use disorders, to improve emotional regulation and decision-making [5].

- Circuit-Guided Cell Therapy: Stem cell treatments are being combined with neurogenesis-promoting strategies to repair damaged circuits, showing promise for recovery after stroke and in neurodegenerative diseases [5].

- Multifunctional Probes: Tools like Tetrocysteine Display of Optogenetic Elements (Tetro-DOpE) allow for real-time monitoring and modification of neuronal populations, increasing the precision of circuit-level interventions [5].

The BRAIN Initiative's investment in fundamental, disease-agnostic neuroscience has created an ecosystem that is accelerating the transition toward precision neuromedicine. By providing the tools, maps, and fundamental principles of brain circuit operation, the initiative is laying the groundwork for more effective, targeted, and personalized treatments for a wide range of neurological and psychiatric disorders [1] [5].

The study of key neuroanatomical structures—gray matter, white matter, and neural networks—has been revolutionized by advances in whole brain imaging techniques. These non-invasive methods allow researchers to quantitatively investigate the structure and function of neural pathways in both healthy and diseased states [6]. Neuroimaging serves as a critical window into the mind, enabling the mapping of complex brain networks and providing insights into the neural underpinnings of various cognitive processes and neurological disorders [7] [6]. This field combines neuroscience, computer science, psychology, and statistics to objectively study the human brain, with recent technological developments allowing unprecedented resolution in visualizing and quantifying brain structures and their interactions [8] [6].

Quantitative Comparison of Gray and White Matter Properties

Advanced neuroimaging techniques have enabled the precise quantitative comparison of gray and white matter properties across different conditions and field strengths. These measurements provide crucial insights into brain microstructure and function.

Table 1: Quantitative Magnetic Resonance Imaging Comparison of Normal vs. Ectopic Gray Matter

| Parameter | Normal Gray Matter (NGM) | Gray Matter Heterotopia (GMH) | Statistical Significance | Measurement Technique |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CBF (PLD 1.5s) | 52.69 mL/100 g/min | 31.96 mL/100 g/min | P<0.001 | Arterial Spin Labeling (ASL) |

| CBF (PLD 2.5s) | 56.93 mL/100 g/min | 35.13 mL/100 g/min | P<0.001 | Arterial Spin Labeling (ASL) |

| Normalized CBF | Significantly higher | Significantly lower | P<0.001 | ASL normalized against white matter |

| T1 Values | Distinct profile | Distinct profile | P<0.001 | MAGiC quantitative sequence |

| T2 Values | No significant difference from GMH | No significant difference from NGM | P>0.05 | MAGiC quantitative sequence |

| Proton Density | No significant difference from GMH | No significant difference from NGM | P>0.05 | MAGiC quantitative sequence |

Table 2: Technical Specifications of Imaging Systems for Gray-White Matter Contrast Analysis

| Parameter | 1.5 Tesla MRI | 3.0 Tesla MRI | Significance/Application |

|---|---|---|---|

| Single-slice CNR(GM-WM) | 13.09 ± 2.35 | 17.66 ± 2.68 | P<0.001, superior at 3T [9] |

| Multi-slice CNR (0% gap) | 7.43 ± 1.20 | 8.61 ± 2.55 | P>0.05, not significant [9] |

| Multi-slice CNR (25% gap) | 9.73 ± 1.37 | 12.47 ± 3.31 | P<0.001, superior at 3T [9] |

| CNR Reduction Rate (0% gap) | 0.38 ± 0.09 | 0.47 ± 0.13 | P=0.02, larger effect at 3T [9] |

| Spatial Resolution | Standard | Up to 1 mm voxels [6] | Enables study of smaller brain structures |

| BOLD Signal Change | Standard | 1-2% on 3T scanner [7] | Varies across brain regions and event types |

Experimental Protocols for Neural Pathways Research

Protocol 1: Quantitative Assessment of Gray Matter Heterotopia Using Advanced MRI

Background: Gray matter heterotopia (GMH) involves abnormal migration of cortical neurons into white matter and is often associated with drug-resistant epilepsy [10]. This protocol uses quantitative MRI techniques to characterize differences between ectopic and normal gray matter.

Materials and Equipment:

- 3.0 T MRI system (e.g., SIGNA Architect, GE HealthCare)

- T1 BRAVO sequence parameters: TR 7,800 ms, TE 31 ms, slice thickness 1 mm, FOV 256 mm × 230 mm, matrix size 256×256, flip angle 8°

- T2-weighted imaging parameters: TR 4,500 ms, TE 120 ms, slice thickness 5 mm, slice gap 1.5 mm, FOV 240 mm × 240 mm, matrix size 320×256, flip angle 111°

- Arterial Spin Labeling (ASL) sequences with postlabeling delays of 1.5 s and 2.5 s

- MAGiC (Magnetic Resonance Image Compilation) sequence based on 2D fast spin echo technology

Procedure:

- Subject Preparation: Enroll patients with complete imaging data and confirmed GMH diagnosis. Ensure inclusion criteria: presence of cortical-like signal nodule within normal white matter and history of at least three epileptic seizures or abnormal EEG findings.

- Data Acquisition: Perform complete MRI protocol including T1 BRAVO, T2WI, MAGiC, and ASL sequences with dual postlabeling delays.

- Quantitative Measurements: Manually measure regions of interest (ROIs) for GMH, normal gray matter (NGM), and normal white matter (NWM). For patients with multiple GMH, record each separately but treat as one patient for clinical statistics.

- Data Normalization: Normalize quantitative values obtained from GMH and NGM against contralateral white matter visually identified as normal.

- Statistical Analysis: Use paired-sample t-tests to compare quantitative values between NGM and GMH before and after normalization.

Applications: This protocol is particularly valuable for preoperative planning in epilepsy surgery and understanding the functional differences between ectopic and normal gray matter tissues [10].

Protocol 2: Functional Connectivity and Network Analysis Using BrainNet Viewer

Background: The human brain is organized into complex structural and functional networks that can be represented using connectomics [11]. This protocol details the visualization and analysis of these neural networks.

Materials and Equipment:

- MATLAB environment with BrainNet Viewer toolbox

- Brain surface templates (e.g., Ch2, ICBM152)

- Node and edge files defining brain network parcellation

- Network analysis toolkits (Brain Connectivity Toolbox, Graph-theoRETical Network Analysis toolkit)

Procedure:

- Data Preparation: Prepare input files containing connectome information:

- Brain surface file (.nv): Contains number of vertices, coordinates, number of triangle faces, and vertex indices

- Node file (.node): Includes x, y, z coordinates, node color index, node size, and node labels

- Edge file (.edge): Association matrix representing connections between nodes

- Volume file: Functional connectivity map, statistical parametric map, or brain atlas

Toolbox Configuration: Load the combination of files in BrainNet Viewer GUI. Adjust figure configuration parameters including output layout, background color, surface transparency, node color and size, edge color and size, and image resolution.

Network Visualization: Generate ball-and-stick models of brain connectomes. Implement volume-to-surface mapping and construct ROI clusters from volume files.

Connectome Analysis: Apply graph theoretical algorithms to measure topological properties including small-worldness, modularity, hub identification, and rich-club configurations.

Output Generation: Export figures in common image formats or demonstration videos for further analysis and publication.

Applications: This protocol enables researchers to investigate relationships between brain network properties and population attributes including aging, development, gender, intelligence, and various neuropsychiatric disorders [11].

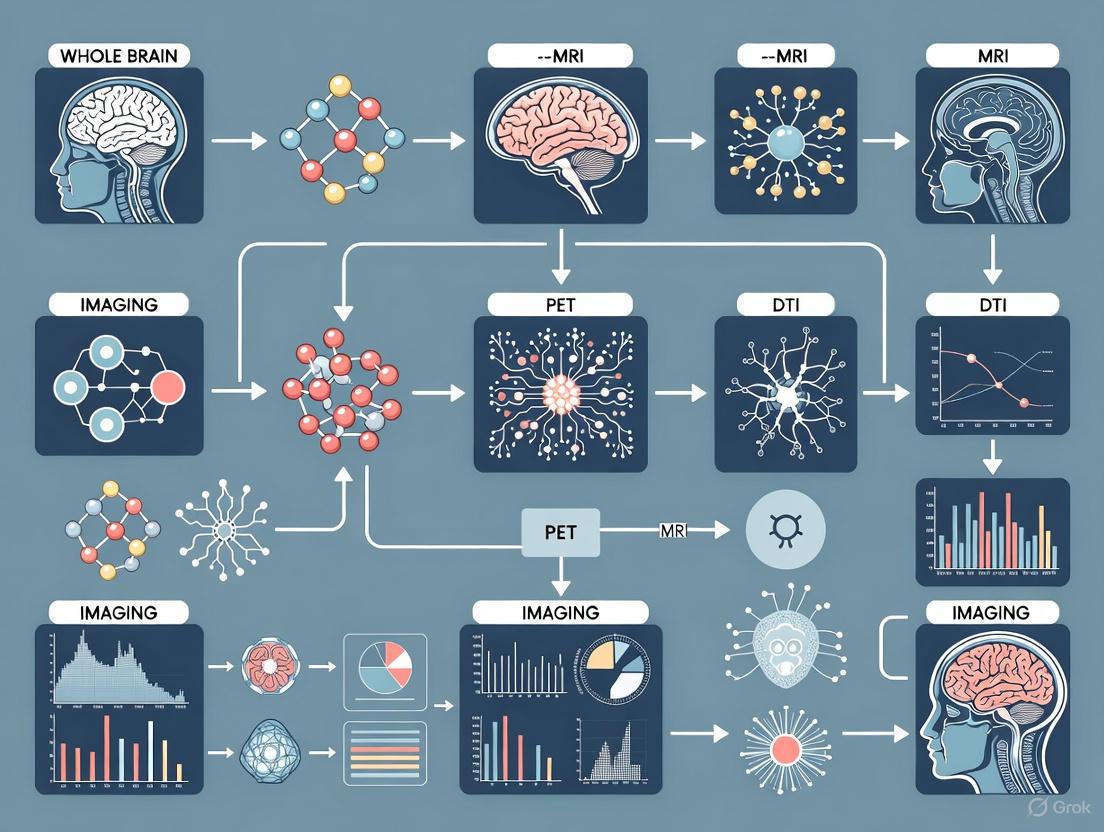

Visualization of Neuroimaging Workflows and Signaling Pathways

Figure 1: Comprehensive workflow for neuroimaging analysis from data acquisition to clinical interpretation, highlighting the integration of structural and functional imaging techniques.

Figure 2: Relationship between key neuroanatomical structures and specialized imaging modalities used for their investigation in neural pathways research.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Neural Pathways Imaging

| Item | Function/Application | Example Specifications |

|---|---|---|

| 3.0 T MRI Scanner | High-field magnetic resonance imaging for structural and functional studies | SIGNA Architect (GE HealthCare); enables voxel sizes as small as 1 mm [6] |

| Arterial Spin Labeling (ASL) | Non-invasive measurement of cerebral blood flow without contrast agents | Postlabeling delays of 1.5 s and 2.5 s; TR 4,838 ms, TE 57.4 ms [10] |

| MAGiC Sequence | Quantitative mapping of T1, T2, and proton density values in a single scan | Based on 2D fast spin echo; FOV 24 cm × 19.2 cm; TR 4,000 ms; TE 21.4 ms [10] |

| BrainNet Viewer | Graph-theoretical network visualization toolbox for connectome mapping | MATLAB-based GUI; supports multiple surface templates and network files [11] |

| EEG Recording System | Measurement of electrical brain activity with high temporal resolution | 64-256 electrodes; captures event-related potentials and oscillatory activity [7] |

| FDG-PET Tracer | Assessment of glucose metabolism in brain regions | [18F]fluorodeoxyglucose; particularly useful for epilepsy and dementia evaluation [8] |

| Graph Analysis Toolboxes | Quantification of network properties (small-worldness, modularity, hubs) | Brain Connectivity Toolbox (BCT), GRETNA, NetworkX [11] |

Connectomics is an emerging subfield of neuroanatomy explicitly aimed at quantitatively elucidating the wiring of brain networks with cellular resolution and quantified accuracy [12]. The term "connectome" describes the complete, precise wiring diagram of neuronal connections in a brain, encompassing everything from individual synapses to entire brain-wide networks [12]. Such wiring diagrams are indispensable for realistic modeling of brain circuitry and function, as they provide the structural foundation upon which neural computation is built [12]. The only complete connectome produced to date remains that of the small worm Caenorhabditis elegans, which has just 302 neurons [12], highlighting the immense technical challenge of mapping more complex nervous systems.

The field has developed extremely rapidly in the last five years, with particularly impactful developments in insect brains [13]. Increased electron microscopy imaging speed and improvements in automated segmentation now make complete synaptic-resolution wiring diagrams of entire fruit fly brains feasible [13]. As methods continue to advance, connectomics is progressing from mapping localized circuits to tackling entire mammalian brains, enabling researchers to test hypotheses of circuit function across a variety of behaviours including learned and innate olfaction, navigation, and sexual behaviour [13].

Imaging Technologies for Connectome Reconstruction

Connectome reconstruction requires imaging technologies capable of resolving neural structures across multiple scales, from nanometer-resolution synapses to centimeter-scale whole brains. The table below summarizes the primary imaging modalities used in connectomics research.

Table 1: Imaging Technologies for Connectome Reconstruction

| Technology | Resolution | Scale | Primary Applications | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Electron Microscopy (EM) [13] [12] | 4×4×30 nm³ [14] | Local circuits to whole insect brains [13] | Synaptic-resolution connectivity mapping | Sample preparation complexity, massive data volumes |

| Serial Block-Face SEM (SBEM) [15] | ~4×4×30 nm³ [14] | Up to ~1 mm³ volumes [14] | Dense reconstruction of cortical microcircuits | Limited volume size, sectioning artifacts |

| Focused Ion Beam SEM (FIB-SEM) [13] | ~4×4×30 nm³ [14] | Smaller volumes than SBEM | Subcellular analysis, morphological diversity | Smaller volumes than SBEM |

| Computational Scattered Light Imaging (ComSLI) [16] | Micrometer resolution [16] | Human tissue samples | Fiber orientation mapping in historical specimens | Lower resolution than EM |

| Light Microscopy (LM) [12] | Diffraction-limited | Whole brains | Cell type identification, sparse labeling | Cannot resolve individual synapses |

Electron microscopy approaches, particularly serial-section transmission EM and focused ion beam scanning EM, have proven essential for synaptic-resolution connectomics [13]. These methods provide the nanometer resolution necessary to unambiguously identify synapses, gap junctions, and other forms of adjacency among neurons in complex neural systems [17]. Recent advances have made pipelines more robust through improvements in sample preparation, image alignment, and automated segmentation methods for both neurons and synapses [13].

A promising development is Computational Scattered Light Imaging (ComSLI), a fast and low-cost computational imaging technique that exploits scattered light to visualize intricate networks of fibers within human tissue [16]. This method requires only a rotating LED lamp and a standard microscope camera to record light scattered from samples at different angles, making it accessible to any laboratory [16]. Unlike many specialized techniques, ComSLI can image specimens created using any preparation method, including tissues preserved and stored for decades, opening new possibilities for studying historical specimens and tracing the lineage of hereditary diseases [16].

Connectome Reconstruction Workflows

The process of reconstructing connectomes from imaging data involves multiple steps, each with specific technical challenges and required solutions. The typical workflow includes data acquisition, registration, segmentation, proofreading, and analysis [14].

Table 2: Connectomics Workflow Steps and Challenges

| Workflow Step | Key Tasks | Technical Challenges | Tools & Solutions |

|---|---|---|---|

| Data Acquisition [14] | Sample preparation, EM imaging | Signal-to-noise ratio, contrast artifacts, data volume (petabytes) [14] | MBeam viewer for quality assessment [14] |

| Registration [14] | Align image tiles into 2D sections, then into 3D volume | Stitching accuracy, handling massive data | RHAligner visualization scripts [14] |

| Segmentation [14] | Identify cell membranes, classify neurons and synapses | Distinguishing tightly packed neural structures | RhoANAScope for image and label overlay [14] |

| Proofreading [13] [14] | Correct segmentation errors | Labor-intensive, requires expert knowledge | Dojo, Guided Proofreading [14] |

| Analysis [14] | Extract connectivity graphs, analyze network properties | Modeling complex networks, visualization | 3DXP, Neural Data Queries [14] |

Diagram 1: Connectomics reconstruction workflow

Automated Reconstruction with Artificial Intelligence

Substantial progress has been made in automating connectome reconstruction through artificial intelligence approaches. RoboEM represents a significant advance—an artificial intelligence-based self-steering 3D "flight" system trained to navigate along neurites using only 3D electron microscopy data as input [15]. This system mimics the process of human flight-mode annotation in 3D but does so automatically, substantially improving automated state-of-the-art segmentations [15].

RoboEM can replace manual proofreading for complex connectomic analysis problems, reducing computational annotation costs for cortical connectomes by approximately 400-fold compared to manual error correction [15]. When applied to challenging reconstruction tasks such as resolving split errors (incomplete segments) and merger errors (incorrectly joined segments), RoboEM successfully handled 76% of ending queries and 78% of chiasma queries without errors, performing comparably to human annotators [15].

Experimental Protocols for Connectome Generation

Sample Preparation for Synaptic-Resolution Connectomics

Objective: Prepare brain tissue for synaptic-resolution electron microscopy imaging.

Materials:

- Brain tissue samples (fresh or preserved)

- Resin embedding materials

- Ultramicrotome for sectioning

- Heavy metal stains (osmium tetroxide, uranyl acetate)

- Automated tape-collecting ultramicrotome (ATUM) for large volumes [15]

Procedure:

- Fixation: Perfuse tissue with glutaraldehyde and paraformaldehyde fixatives to preserve ultrastructure.

- Staining: Apply heavy metal stains to enhance membrane contrast for EM imaging.

- Dehydration: Gradually replace water with organic solvents (ethanol or acetone).

- Embedding: Infuse with resin and polymerize to create solid blocks.

- Sectioning: Cut ultrathin sections (30-40 nm thickness) using an ultramicrotome.

- Collection: For large volumes, use ATUM to collect sections on tape for automated imaging [15].

Quality Control: Assess section quality by light microscopy, check for wrinkles, tears, or staining artifacts.

Computational Scattered Light Imaging (ComSLI) Protocol

Objective: Map fiber orientations in neural tissue using scattered light patterns.

Materials:

- Standard microscope with camera

- Rotating LED lamp

- Tissue samples (fresh, preserved, or historical specimens)

- Computational processing software

Procedure:

- Sample Mounting: Place tissue sample on microscope slide.

- Illumination: Illuminate sample with LED lamp at multiple rotation angles.

- Image Acquisition: Capture scattered light patterns at each angle.

- Pattern Analysis: Compute fiber orientations from light scattering patterns.

- Mapping: Generate orientation maps color-coded for fiber direction and density.

Applications: This fast, low-cost method can reveal densely interconnected fiber networks in healthy tissue and deterioration in disease models like Alzheimer's [16]. It successfully imaged a brain tissue specimen from 1904, demonstrating unique capability with historical samples [16].

Data Management and Visualization Solutions

Connectomics generates massive datasets that pose significant informatics challenges. A typical 1mm³ volume of brain tissue imaged at 4×4×30nm³ resolution produces 2 petabytes of image data [14]. Managing these datasets requires specialized informatics infrastructure.

The BUTTERFLY middleware provides a scalable platform for handling massive connectomics data for interactive visualization [14]. This system outputs image and geometry data suitable for hardware-accelerated rendering and abstracts low-level data wrangling to enable faster development of new visualizations [14]. The platform includes open source Web-based applications for every step of the typical connectomics workflow, including data management, informative queries, 2D and 3D visualizations, interactive editing, and graph-based analysis [14].

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Connectomics

| Resource | Type | Function | Access |

|---|---|---|---|

| Virtual Fly Brain [13] | Database | Drosophila neuroanatomy resource with rich vocabulary for cell types | https://virtualflybrain.org |

| neuPrint [13] | Analysis Tool | Connectome analysis platform for EM segmentation data | https://neuprint.janelia.org |

| FlyWire [13] | Community Platform | Dense reconstruction proofreading community for fly brain data | https://flywire.ai |

| Neuroglancer [13] | Visualization | WebGL-based viewer for volumetric connectomics data | https://github.com/google/neuroglancer |

| natverse [13] | Analysis Tool | Collection of R packages for neuroanatomical analysis | https://natverse.org |

| Butterfly Middleware [14] | Data Management | Scalable platform for massive connectomics data visualization | Open source |

The Human Connectome Project has developed comprehensive informatics tools for quality control, database services, and data visualization [18]. Their approach includes standardized operating procedures to maintain data collection consistency over time, quantitative modality-specific quality assessments, and the Connectome Workbench visualization environment for user interaction with HCP data [18].

Multi-Modal Integration and Analysis

A powerful trend in modern connectomics is the integration of structural connectivity data with other modalities including transcriptomics, physiology, and behavior. This multi-modal approach enriches the interpretation of wiring diagrams and strengthens links between neuronal connectivity and brain function [13].

Machine learning approaches can predict neurotransmitter identity from EM data with high accuracy, aiding in the interpretation of connectivity features and supporting functional observations [13]. Single-cell transcriptomic approaches are increasingly prevalent, with comprehensive whole adult data now available for integration with connectomic cell types [13].

A 2025 study demonstrated the integration of morphological information from Patch-seq to predict transcriptomically defined cell subclasses of inhibitory neurons within a large-scale EM dataset [19]. This approach successfully classified Martinotti cells into somatostatin-positive MET-types with distinct axon myelination and synaptic output connectivity patterns, revealing unique connectivity rules for predicted cell types [19].

Diagram 2: Multi-modal data integration

Applications in Neural Pathways Research

Connectomics has enabled fundamental discoveries about neural pathway organization and function across multiple species and brain regions. In the mouse retina, connectomic reconstruction of the inner plexiform layer revealed the precise wiring underlying direction selectivity [17]. In Drosophila, complete wiring diagrams have provided insights into interconnected modules with hierarchical structure, recurrence, and integration of sensory streams [13].

Comparative connectomics across development, experience, sex, and species is establishing strong links between neuronal connectivity and brain function [13]. Comparing individual connectomes helps determine which circuit features are robust and which are variable, addressing key questions about the relationship between structure and function in neural systems [13].

The application of connectomics to disease states is particularly promising. ComSLI has demonstrated clear deterioration in the integrity and density of fiber pathways in Alzheimer's disease tissue, with one of the main routes for carrying memory-related signals becoming barely visible [16]. Such findings highlight the potential of connectomic approaches to reveal the structural basis of neurological disorders.

Whole-brain imaging represents a paradigm shift in neuroscience, enabling the precise dissection of neural pathways across multiple scales. This Application Note details integrated methodologies for three complementary objectives: the localization of neural structures at single-cell resolution, the mapping of functional and structural connectivity, and the prediction of clinical outcomes through network-level analysis. Framed within a broader thesis on advanced neural pathway research, these protocols provide a foundational toolkit for scientists aiming to bridge microscopic anatomy with system-level brain function, with direct implications for drug discovery and the study of neurological disorders.

Localization: Whole-Brain Cellular Phenotyping

The precise localization and quantification of cells across the entire brain is a cornerstone of mesoscopic analysis, providing a structural basis for understanding neural circuits.

Experimental Protocol: Whole-Brain Tissue Clearing and Light-Sheet Imaging

Title: Protocol for iDISCO+ Tissue Clearing and Light-Sheet Microscopy of the Mouse Brain [20]

Objective: To prepare and image an intact postnatal day 4 (P4) mouse brain for whole-brain, single-cell resolution analysis.

Workflow Diagram:

Procedure:

- Perfusion and Fixation: Administer pentobarbital (100 mg/kg, i.p.) to achieve a surgical plane of anesthesia. Perform transcardial perfusion first with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) to clear blood, followed by ice-cold 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA) containing a gadolinium-based MRI contrast agent. Post-fix the intact skull in 4% PFA for 24 hours at 4°C [20].

- Pre-Clearing MRI (Optional): Incubate the skinless skull in PBS with 3% gadolinium for 23 days at 4°C. Image using a 9.4T MRI system with a spin-echo sequence (60 µm isotropic resolution). This provides a pre-clearing anatomical reference to quantify tissue shrinkage [20].

- iDISCO+ Tissue Clearing:

- Dehydrate the sample in a series of methanol/H₂O gradients.

- Delipidate in dichloromethane.

- Perform refractive index matching by immersion in dibenzyl ether (DBE), rendering the brain transparent [20].

- Light-Sheet Fluorescence Microscopy (LSFM): Image the cleared brain using a light-sheet microscope. The protocol enables rapid acquisition of the entire brain at cellular resolution, generating terabytes of image data [20].

- Computational Analysis with NuMorph: Process the LSFM data to correct intensity variations, stitch image tiles, align channels, and perform automated nuclei counting. Register the resulting dataset to a standard brain atlas for region-specific quantification [20].

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 1: Essential Reagents for Whole-Brain Clearing and Imaging

| Reagent / Material | Function | Application Note |

|---|---|---|

| Paraformaldehyde (PFA) | Cross-linking fixative | Preserves tissue architecture; 4% solution is standard for perfusion [20]. |

| Gadolinium Contrast Agent | MRI signal enhancement | Used for pre-clearing magnetic resonance imaging to measure initial brain volume [20]. |

| Methanol and Dichloromethane | Dehydration and delipidation | Organic solvents in iDISCO+ protocol that remove water and lipids, key for clearing [20]. |

| Dibenzyl Ether (DBE) | Refractive index matching medium | Final immersion medium (RI~1.56) that renders the tissue transparent for LSFM [20]. |

| Anti-NeuN/Anti-GFP Antibodies | Immunohistochemical labeling | Allows specific targeting of neurons or fluorescent proteins in cleared tissue [4]. |

| NuMorph Software | Nuclear segmentation & analysis | Quantifies all nuclei and nuclear markers within annotated brain regions [20]. |

Connectivity: Mapping the Mammalian Connectome

Moving beyond static localization, understanding brain function requires mapping the intricate web of structural and functional connections, known as the connectome.

Multi-Scale Connectivity Analysis Workflow

Title: Multi-Scale Mammalian Connectome Analysis [21]

Objective: To identify and compare information transmission pathways in mammalian brain networks across species (mouse, macaque, human).

Workflow Diagram:

Protocol: MultiLink Analysis for Case-Control Connectomics

Title: Sparse Connectivity Analysis with MultiLink Analysis (MLA) [22]

Objective: To identify the multivariate relationships in brain connections that best characterize the differences between two experimental groups (e.g., healthy controls vs. patients).

Procedure:

- Data Preparation: Represent each subject's brain connectivity as a vectorized connectivity matrix. Assemble these into an

n × pdata-matrixX, wherenis the number of subjects andpis the number of connections. Encode group membership in an indicator matrixY[22]. - Sparse Discriminant Analysis (SDA): Apply a regularized linear discriminant analysis to find discriminant vectors

βkthat solve the convex optimization problem [22]:

min ‖Yθk - Xβk‖² + η‖βk‖₁ + γβkᵀΩβkTheℓ₁-norm penalty (η‖βk‖₁) enforces sparsity, selecting a minimal set of discriminative connections.

- Stability Selection: Iterate the SDA model over multiple bootstrap subsamples of the dataset. Retain only the connections that are consistently selected across iterations, ensuring robust and reproducible feature selection [22].

- Subnetwork Identification: The final output is a sparse subnetwork of connections that reliably differentiates the two groups, providing an interpretable biomarker for the condition under study [22].

Table 2: Comparative Information Transmission in Mammalian Brains [21]

| Species | Brain Weight | Neuron Count | Selective Transmission | Parallel Transmission |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mouse | ~0.42 g | ~70 million | Predominant mode | Limited |

| Macaque | ~87.35 g | ~6.37 billion | Predominant mode | Limited |

| Human | ~1350 g | ~86 billion | Limited | Predominant mode |

Note: Parallel transmission in humans acts as a major connector between unimodal and transmodal systems, potentially supporting complex cognition.

Table 3: Performance of Connectivity-Based Classification [23]

| Classification Approach | Accuracy | Sensitivity | Specificity | AUC |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Region-Based | 74% | 78% | 76% | 0.69 - 0.80 |

| Pathway-Based | 83% | 86% | 78% | 0.75 - 0.90 |

Note: The pathway-based approach infers activity across 59 pre-defined brain pathways, outperforming single-region analysis for classifying Alzheimer's disease and amnestic mild cognitive impairment.

Prediction: From Connectivity to Clinical Outcomes

The ultimate application of connectome analysis is the development of predictive models for disease classification and progression.

Protocol: Brain Pathway Activity Inference for AD Classification

Title: Inference of Disrupted Brain Pathway Activities in Alzheimer's Disease [23]

Objective: To classify Alzheimer's disease (AD) and amnestic mild cognitive impairment (aMCI) patients from cognitively normal (CN) subjects based on inferred brain pathway activities.

Workflow Diagram:

Procedure:

- Data Acquisition & Preprocessing: Acquire resting-state fMRI (RS-fMRI) data from AD, aMCI, and CN subjects. Preprocess using FSL 4.1, including motion correction, spatial smoothing, and registration to MNI standard space [23].

- Functional Connectivity Matrix: Parcellate the brain into 116 regions using the Automated Anatomical Labeling (AAL) atlas. Extract the average BOLD time series from each region and compute a 116 x 116 pairwise functional connectivity matrix for each subject [23].

- Integrate Brain Pathway Database: Curate a set of 59 brain pathways from literature, each comprising anatomically separate but functionally connected regions involved in specific behavioral domains (e.g., cognition, emotion, sensation) [23].

- Pathway Activity Inference: For each of the 59 pathways, use an exhaustive search algorithm to infer a single activity value that best represents the integrated functional connectivity within that pathway for a given subject [23].

- Classification: Use the inferred activity levels of the 59 pathways as features in a classifier (e.g., support vector machine) to discriminate between patient groups and controls. This pathway-based approach has been shown to outperform models based on single-region activities [23].

Integrated Discussion

The synergy between localization, connectivity, and prediction creates a powerful framework for holistic brain research. High-resolution cellular localization provides the ground truth for structural connectomes, while functional connectivity reveals the dynamic interactions within these networks. Ultimately, the integration of these data layers enables robust predictive models of brain function and dysfunction.

Techniques like tissue clearing and light-sheet microscopy [24] [4] [20] have revolutionized our ability to localize cells and projections across the entire brain, providing unprecedented mesoscopic detail. The discovery that human brains exhibit a fundamentally different, parallel information routing architecture compared to mice and macaques [21] highlights the critical importance of cross-species connectomics. This finding was made possible by graph- and information-theory models that move beyond simple connectivity to infer information-related pathways. Finally, translating these insights into clinically actionable tools is demonstrated by pathway-based classifiers, which successfully handle the heterogeneity of neurological disorders like Alzheimer's disease to achieve high classification accuracy [22] [23].

For drug development professionals, this integrated approach offers a clear path from mechanistic studies in animal models to human clinical application. The protocols detailed herein provide a roadmap for identifying novel therapeutic targets, validating their role within brain networks, and developing biomarkers for patient stratification and treatment efficacy monitoring.

The quest to visualize the brain's intricate architecture began in earnest in the 1870s with Camillo Golgi's development of the "black reaction," a staining technique that revolutionized neuroscience by revealing entire neurons for the first time [25]. This seminal breakthrough provided the foundational tool that enabled Santiago Ramón y Cajal to formulate the neuron doctrine, which established that neurons are discrete cells that communicate via synapses [25]. The Golgi staining technique, which involves hardening neural tissue in potassium dichromate followed by immersion in silver nitrate to randomly stain approximately 1-10% of neurons black against a pale yellow background, allowed scientists to trace individual neuronal projections through dense brain tissue for the first time [25]. This historical technique has evolved through numerous modifications and continues to inform twenty-first-century research, now integrated with advanced computational methods that enable whole-brain mapping at single-cell resolution [25] [26]. This application note traces this technological evolution, providing detailed protocols and analytical frameworks for researchers investigating neural pathways in both basic research and drug development contexts.

Golgi Staining: Foundational Protocol and Modern Adaptations

Original Golgi Staining Methodology

The classical Golgi staining protocol developed by Camillo Golgi involves a series of precise chemical processing steps designed to impregnate a small subset of random neurons for detailed morphological analysis [25] [27]. The original procedure requires careful execution under specific conditions to achieve consistent results:

- Tissue Hardening: Fresh brain samples are immersed in a 2.5% potassium dichromate solution for up to 45 days to harden the soft neural tissue [25].

- Silver Impregnation: Samples are subsequently transferred to a 0.5-1% silver nitrate solution for varying durations, which deposits metallic silver within randomly selected neurons, staining them black while leaving surrounding tissue relatively transparent [25].

- Dehydration and Sectioning: Following impregnation, tissues are dehydrated through an alcohol series, sliced into 100μm sections (approximately the thickness of a paper sheet) using a microtome, cleared in turpentine, and mounted on slides with gum damar for preservation [25].

Table 1: Key Solutions for Traditional Golgi Staining

| Solution Component | Concentration | Function | Processing Time |

|---|---|---|---|

| Potassium Dichromate | 2.5% | Tissue hardening & fixation | Up to 45 days |

| Silver Nitrate | 0.5-1% | Neuronal impregnation | Variable, 1-3 days |

| Ethanol Series | 50-100% | Tissue dehydration | 5-10 min per step |

| Turpentine | 100% | Tissue clearing | 5-10 min |

| Gum Damar | N/A | Mounting medium | Permanent preservation |

Modern Golgi-Cox Modifications

The Golgi-Cox method represents a significant advancement over the original technique, offering improved reliability and reduced precipitation artifacts [28] [27]. This modification uses mercuric chloride, potassium dichromate, and potassium chromate in combination to impregnate neurons, followed by ammonia development to reveal the stained cells [27]. The protocol has been extensively optimized for consistency:

- Solution Preparation: Three stock solutions (5% w/v each of potassium dichromate, mercuric chloride, and potassium chromate) are prepared in double-distilled water and stored in the dark at room temperature [27]. The working Golgi-Cox solution is prepared by mixing 50ml potassium dichromate, 50ml mercuric chloride, 40ml potassium chromate, and 100ml dd-H₂O, then allowing the solution to settle for 48 hours before use [27].

- Impregnation Protocol: Freshly dissected brain tissue (either perfused or non-perfused) is immersed in Golgi-Cox solution and stored in complete darkness at room temperature for 7-10 days, with solution change after the first 24 hours [27]. For human autopsy tissue, impregnation may extend beyond 10 weeks to ensure complete staining [29].

- Sectioning and Development: Tissue is protected with a sucrose-polyvinylpyrrolidone-ethylene glycol cryoprotectant solution, sectioned at 200μm using a vibratome, and developed through a series of steps including ammonia treatment, sodium thiosulfate fixation, dehydration through ethanol and butanol, clearing in xylene, and mounting on gelatin-coated slides [27].

Figure 1: Original Golgi Staining Workflow

Heat-Enhanced Rapid Golgi-Cox Staining

Recent innovations have significantly reduced the impregnation time required for Golgi-Cox staining through temperature optimization. By maintaining tissue blocks at 37±1°C during chromation, complete neuronal staining can be achieved within just 24 hours compared to weeks with traditional methods [28] [30]. The rapid protocol follows these critical steps:

- Temperature-Controlled Impregnation: Brain blocks (5mm thick) are immersed in Golgi-Cox solution and maintained at 37°C in an incubator for 24 hours, dramatically accelerating the metallic ion infusion into neurons [28] [30].

- Quality Assessment: Staining initiation is identified by distinct black nucleation spots within neurons without surrounding spillover, with complete staining defined by well-demarcated soma, axons, and dendrites [30].

- Enhanced Permeability: The addition of 0.1-0.2% sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) or 0.5% Triton X-100 to the Golgi-Cox solution further improves stain penetration, particularly when combined with elevated temperatures [28].

For even faster processing, a 2025 modification demonstrates that incubation at 55°C enables high-quality staining of 100μm-thick mouse brain sections in merely 24 hours while maintaining compatibility with immunostaining techniques, enabling correlative analysis of neuronal morphology and protein expression [31].

Table 2: Evolution of Golgi Staining Methodologies

| Method | Key Components | Impregnation Time | Key Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Original Golgi (1873) | Potassium dichromate, Silver nitrate | 45+ days | High-resolution neuronal detail | Inconsistent, extremely long processing |

| Golgi-Cox Modification | Mercuric chloride, Potassium dichromate, Potassium chromate | 7-80 days | More reliable, better dendritic detail | Still time-consuming, mercury toxicity |

| NeoGolgi (2014) | Extended impregnation (>10 weeks), rocking platform | 10+ weeks | Exceptional for human autopsy tissue, stable for years | Very long processing time |

| Heat-Enhanced (2010) | 37°C incubation, Golgi-Cox solution | 24 hours | Rapid, reproducible, inexpensive | Requires temperature control |

| Ultra-Rapid (2025) | 55°C incubation, Golgi-Cox solution | 24 hours | Fastest method, immunostaining compatible | Very new method, limited validation |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Solutions

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Golgi Staining and Whole-Brain Imaging

| Reagent/Solution | Composition/Example | Primary Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Golgi-Cox Impregnation Solution | Potassium dichromate, Mercuric chloride, Potassium chromate in dd-H₂O | Random neuronal impregnation via metal deposition | Golgi-Cox staining [27] |

| Tissue Cryoprotectant Solution | Sucrose, PVP, Ethylene glycol in phosphate buffer | Prevents ice crystal formation, maintains tissue integrity | Tissue protection pre-sectioning [27] |

| Ammonia Developer | 3:1 Ammonia:dd-H₂O | Reduces metallic salts to reveal stained neurons | Post-sectioning development [27] |

| CUBIC Reagents | Aminoalcohol-based chemical cocktails | Tissue clearing via refractive index matching | Whole-brain imaging [26] |

| Lipophilic Tracers | DiI, DiO, DiD combinations | Multicolor neuronal membrane labeling | "DiOlistic" labeling [29] |

Computational Integration: From Microscopy to Whole-Brain Modeling

Whole-Brain Imaging and Clearing Techniques

The integration of chemical clearing methods with advanced microscopy has enabled unprecedented visualization of neural pathways at the whole-brain scale. The CUBIC (Clear, Unobstructed Brain Imaging Cocktails and Computational Analysis) method represents a significant advancement in this domain, featuring:

- Chemical Cocktails: Aminoalcohol-based solutions that efficiently clear entire adult brains while preserving fluorescent proteins and enabling immunostaining [26].

- Single-Cell Resolution: When coupled with light-sheet or single-photon excitation microscopy, CUBIC enables comprehensive imaging of neural structures throughout the entire brain with single-cell resolution [26].

- Computational Analysis: Advanced image processing pipelines quantify neural activities and morphological changes in response to experimental manipulations or environmental stimuli [26].

This approach facilitates time-course expression profiling of complete adult brains, enabling researchers to track developmental changes, disease progression, and treatment effects across entire neural systems rather than being limited to sampled regions [26].

Estimating Effective Connectivity from Neuroimaging

Modern computational neuroscience has developed sophisticated approaches to infer effective connectivity (EC) - the directed influence between brain regions - from structural and functional neuroimaging data. A novel computational framework introduced in 2019 enables:

- Whole-Brain Coverage: Estimation of effective connectivity across the entire connectome rather than being limited to predefined regions of interest [32].

- Gradient Descent Optimization: The approach employs iterative optimization that adjusts structural connectivity weights to maximize similarity between empirical and model-based functional connectivity [32].

- Nonlinear Neural Mass Modeling: Utilizes a supercritical Hopf bifurcation model that captures the oscillatory nature of BOLD signals and incorporates region-specific responsiveness to inputs [32].

The algorithm follows the principle: ΔEC(i,j) = ε(FCemp(i,j) - FCmod(i,j)), where effective connections are updated based on the difference between empirical and model functional connectivity, with ε representing a learning constant [32]. This method has demonstrated particular utility in tracking the development of language pathways from childhood to adulthood, revealing how effective connections between core language regions strengthen with maturation [32].

Figure 2: Computational Estimation of Effective Connectivity

Advanced Computational Intelligence Methods

The increasing complexity of whole-brain imaging data has necessitated the development of advanced computational approaches for data processing and interpretation:

- Deep Learning Architectures: Convolutional neural networks enable automated segmentation of brain structures and lesion detection from MRI data, with fully connected conditional random fields refining the segmentation boundaries [33].

- Transfer Learning: Pre-trained models adapted to specific neuroimaging tasks address challenges of limited labeled datasets, particularly valuable for rare neurological conditions [34].

- Multi-View and Multi-Task Learning: These approaches integrate heterogeneous data sources (e.g., structural MRI, DTI, fMRI) to improve prediction accuracy for clinical outcomes such as seizure classification or cognitive decline [34].

- Fuzzy Systems: Handle uncertainty and missing data in neuroimaging datasets, providing robust analytical frameworks when dealing with the inherent variability of biological systems [34].

These computational methods have demonstrated particular utility in traumatic brain injury assessment, where they help standardize interpretation of neuroimaging findings and improve correlation with clinical outcomes [33].

Integrated Applications in Neuroscience Research and Drug Development

Correlative Morphological and Molecular Analysis

The integration of traditional Golgi staining with modern molecular techniques represents a powerful approach for comprehensive neurological assessment. The recently developed rapid heat-enhanced Golgi-Cox method maintains compatibility with immunostaining, enabling researchers to:

- Correlate Structure and Function: Simultaneously visualize neuronal dendritic morphology and microglial activation states in disease models, revealing interactions between Golgi-stained neurons and microglial processes [31].

- Assess Therapeutic Efficacy: Quantify drug-induced changes in dendritic spine density and complexity while concurrently monitoring neuroinflammatory responses in the same tissue samples [31].

- Leverage Transgenic Models: Combine Golgi staining with fluorescent protein markers in transgenic animals to study specific neuronal populations within complex circuits [31].

This integrated approach provides a more comprehensive dataset from limited biological samples, particularly valuable in preclinical drug development where both morphological and neuroinflammatory endpoints are critical indicators of therapeutic potential.

Translational Applications in Disease Modeling

Advanced Golgi methodologies coupled with computational analysis have enabled significant insights into neurodevelopmental and neurodegenerative disorders:

- Schizophrenia Research: Golgi analysis of human autopsy tissue has revealed decreased basilar dendrites of pyramidal cells in the medial prefrontal cortex, providing morphological correlates of cognitive dysfunction [29].

- Developmental Studies: Whole-brain effective connectivity mapping has illuminated the maturation of language pathways from childhood to adulthood, showing strengthening of specific corticocortical connections with cognitive development [32].

- Neurotoxicology: Rapid Golgi-Cox protocols enable efficient screening of drug candidates for potential neurodevelopmental toxicity by quantifying changes in dendritic arborization and spine density [28] [31].

- Traumatic Brain Injury: Computational analysis of neuroimaging data helps standardize TBI assessment and improves correlation with long-term functional outcomes, addressing significant heterogeneity in patient responses [33].

The continued refinement of these integrated histological and computational approaches will accelerate both basic neuroscience discoveries and the development of novel therapeutics for neurological and psychiatric disorders. By bridging historical staining techniques with modern computational analytics, researchers can now interrogate neural pathways across multiple scales - from individual dendritic spines to whole-brain networks - providing unprecedented insights into brain function in health and disease.

Advanced Imaging Modalities: Technical Approaches and Research Applications

Computational Scattered Light Imaging (ComSLI) represents a transformative advancement in the visualization of microscopic fiber networks within biological tissues. This innovative technique enables researchers to map the orientation and density of neural pathways and other tissue fibers at micrometer resolution using a simple, cost-effective setup. Unlike traditional methods that require specialized equipment and specific sample preparations, ComSLI works with any histology slide, including formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded (FFPE) sections, fresh-frozen samples, and even decades-old archival specimens [35]. This breakthrough is particularly significant for whole brain imaging techniques, as it provides unprecedented access to the intricate wiring of neural networks that form the brain's communication infrastructure.

The fundamental principle underlying ComSLI is based on light-scattering physics: microscopic fibers scatter light predominantly perpendicular to their main axis [36]. By systematically analyzing how light scatters from a tissue sample under different illumination angles, ComSLI reconstructs detailed fiber orientation maps without the need for specialized stains or expensive instrumentation. This accessibility democratizes high-resolution fiber mapping, enabling both small research laboratories and clinical pathology departments to uncover new insights from existing tissue collections [16].

Technical Specifications and Performance Metrics

ComSLI delivers exceptional performance in mapping tissue microarchitecture, with capabilities that surpass existing methodologies in several key aspects. The table below summarizes the quantitative performance data and technical specifications of ComSLI:

Table 1: ComSLI Performance Specifications and Technical Parameters

| Parameter | Specification | Comparative Advantage |

|---|---|---|

| Spatial Resolution | Micrometer-scale (~7 μm) [36] | Exceeds clinical dMRI resolution by 2-3 orders of magnitude |

| Sample Compatibility | FFPE, fresh-frozen, stained, unstained, decades-old specimens [37] [35] | Unprecedented versatility compared to method-specific techniques |

| Equipment Requirements | Rotating LED light source + standard microscope camera [16] | Significantly lower cost than MRI, electron microscopy, or synchrotron-based methods |

| Fiber Crossing Detection | Resolves multiple fiber orientations per pixel [36] | Superior to polarization microscopy and structure tensor analysis |

| Processing Time | Rapid acquisition and processing [38] | Faster than raster-scanning techniques (SAXS, SALS) |

| Field of View | Entire human brain sections [36] | Combines macroscopic coverage with microscopic resolution |

The technical capabilities of ComSLI are further demonstrated by its ability to resolve fiber orientation distributions (μFODs) across multiple scales. At the native 7 μm resolution, approximately 7% of brain pixels contain detectable crossing fibers, but this percentage rises dramatically to 87% and 95% at 500 μm and 1 mm resolutions respectively [36]. This multi-scale analysis capability provides crucial insights for interpreting dMRI data, as it reveals that conventional MRI voxels typically contain multiple crossing fiber populations that would be misinterpreted as single orientations due to resolution limitations.

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

ComSLI Setup and Data Acquisition Protocol

The implementation of ComSLI requires a straightforward experimental setup that can be established in most research laboratories. The following protocol details the essential steps for configuring the system and acquiring scattering data:

Equipment Assembly: Mount a rotatable LED light source around a standard microscope camera. The LED should be positioned at approximately 45° elevation relative to the sample plane [36]. Ensure the camera is equipped with a small-acceptance-angle lens to optimize signal detection.

Sample Mounting: Place the tissue section on a standard microscope slide. No specialized preparation is required—ComSLI works with FFPE sections, fresh-frozen samples, stained or unstained specimens, regardless of storage history [37] [35].

Data Acquisition: Illuminate the sample with the LED light source at multiple rotation angles (typically covering 0-360°). At each angle, capture a high-resolution image of the scattered light pattern using the microscope camera. The number of angular increments can be optimized based on resolution requirements, with finer angular steps providing more detailed orientation information [36].

Signal Processing: For each image pixel, compile the light intensity values across all illumination angles to generate an angular scattering profile I(φ). This profile exhibits characteristic peaks where the scattering intensity is maximized perpendicular to the fiber orientation [36].

The entire acquisition process is significantly faster than raster-scanning techniques like small-angle X-ray scattering (SAXS) and requires only basic optical components compared to specialized microscopy methods.

Fiber Orientation Mapping and Tractography Protocol

Once scattering data is acquired, computational analysis transforms the raw images into detailed fiber orientation maps and tractograms:

Orientation Extraction: Analyze the scattering profile I(φ) for each pixel to identify peak positions using peak detection algorithms. The mid-position between peak pairs indicates the predominant fiber orientation within that pixel [36].

Multi-directional Resolution: For pixels containing crossing fibers, the scattering profile will exhibit multiple peak pairs. Advanced fitting algorithms can disentangle these complex signatures to resolve multiple fiber orientations within a single micrometer-scale pixel [36].

μFOD Calculation: Aggregate orientation information across spatial scales to compute microstructure-informed fiber orientation distributions (μFODs). These distributions represent the probability density of fiber orientations within defined regions of interest, from microscopic clusters to MRI-scale voxels [36].

Tractography: Adapt diffusion MRI tractography tools to utilize the micron-resolution orientation data. Generate orientation distribution functions (ODFs) informed by the microscopic fiber orientations, then implement fiber tracking algorithms to reconstruct continuous axonal pathways through white and gray matter [36].

This protocol enables the reconstruction of detailed whole-brain connectomes from histology sections, providing ground-truth data for validating in vivo imaging techniques and investigating microstructural alterations in disease states.

Research Reagent Solutions and Essential Materials

The accessibility of ComSLI stems from its minimal equipment requirements and compatibility with standard laboratory materials. The following table details the essential components for implementing ComSLI:

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Equipment for ComSLI Implementation

| Component | Function | Specifications/Alternatives |

|---|---|---|

| LED Light Source | Provides directional illumination | Rotatable array with precise angular control; various intensities acceptable |

| Microscope Camera | Captures scattered light patterns | Standard research-grade microscope camera; high dynamic range beneficial |

| Tissue Sections | Imaging specimen | FFPE, fresh-frozen, stained/unstained; any thickness 5-20 μm; decades-old samples suitable |

| Microscope Slides | Sample support | Standard histological slides; no specialized coatings required |

| Computational Resources | Data processing and analysis | Standard workstation; MATLAB, Python, or similar for custom analysis scripts |

| Mounting Media | Sample preservation (optional) | Various media compatible with different preparation methods |

Notably, ComSLI does not require specialized stains, contrast agents, or proprietary reagents. The method leverages the inherent light-scattering properties of tissue microstructures, making it compatible with existing histology collections without additional processing [35]. This retroactive applicability transforms millions of archived slides into valuable data sources for microstructural research.

Applications in Neural Pathway Research and Beyond

Neuroscience and Neurodegenerative Disease Applications

ComSLI has demonstrated exceptional utility in neuroscience research, particularly for investigating the microstructural basis of neural connectivity and its alterations in pathological conditions:

Hippocampal Circuitry in Alzheimer's Disease: Application of ComSLI to hippocampal tissue from Alzheimer's patients revealed striking microstructural deterioration, with marked reduction in the dense fiber crossings that normally characterize this region [35]. Critically, the perforant pathway—a main route for memory-related signals—was barely detectable in Alzheimer's tissue compared to healthy controls [37] [35]. This finding provides a structural correlate for the memory deficits that define the disease.

Multiple Sclerosis Lesion Characterization: In MS tissue, ComSLI successfully identified nerve fiber direction even in areas with significant myelin damage [38]. Furthermore, the technique could differentiate between regions with primarily myelin loss versus those with axonal degeneration, providing crucial pathological discrimination that could inform treatment strategies and disease monitoring.

Historical Neuropathology: ComSLI has successfully visualized fiber architecture in brain sections prepared as early as 1904 [16] [35]. This capability enables contemporary researchers to revisit historical neuropathological collections, potentially uncovering microstructural signatures of disease progression and therapeutic responses across different temporal and treatment contexts.

Non-Neural Tissue Applications

While initially developed for neural tissue, ComSLI's versatility extends to multiple tissue types where fiber organization dictates physiological function:

Muscle Tissue: In tongue muscle, ComSLI revealed layered fiber orientations that correspond to the complex movements required for speech and swallowing [37] [35]. Similar principles apply to other muscular structures throughout the body.

Skeletal Tissue: Bone collagen fibers imaged with ComSLI demonstrate alignment patterns that follow lines of mechanical stress, providing insights into skeletal biomechanics and adaptation [16] [35].

Vascular Networks: Arterial walls examined with ComSLI show alternating layers of collagen and elastin fibers with distinct orientations that provide both structural integrity and elasticity under pulsatile blood flow [37].

These diverse applications highlight ComSLI's potential as a universal tool for investigating tissue microstructure across organ systems and research domains.

Comparative Workflow: ComSLI vs. Traditional Imaging Methods

The diagram below illustrates the streamlined workflow of ComSLI compared to traditional fiber imaging techniques, highlighting key advantages in accessibility and information yield:

Integration with Whole Brain Imaging Techniques

Within the broader context of whole brain imaging, ComSLI occupies a unique niche that bridges resolution scales from microscopic to macroscopic. While diffusion MRI provides in vivo connectivity information at millimeter resolution, and electron microscopy delivers nanometer-level ultrastructural details from minute tissue volumes, ComSLI offers micrometer-resolution fiber mapping across entire brain sections [36]. This positions ComSLI as an ideal validation tool for interpreting dMRI-based tractography, particularly for resolving complex fiber configurations that exceed dMRI's crossing angle sensitivity of approximately 40-45° [36].

The integration of ComSLI with other whole brain imaging approaches creates a powerful multi-scale framework for connectome research. ComSLI can ground-truth dMRI findings by revealing the actual fiber configurations within MRI voxels, while also providing spatial context for targeted electron microscopy studies. Furthermore, ComSLI's compatibility with standard histology stains enables direct correlation between cellular architecture, molecular markers, and fiber pathway organization in the same tissue section [36].

For drug development applications, ComSLI offers a platform for investigating how therapeutic interventions affect neural connectivity at the microstructural level. By applying ComSLI to tissue from animal models or post-mortem human brains, researchers can quantify drug-induced changes in fiber density, orientation complexity, and pathway integrity—metrics that could serve as valuable biomarkers for treatment efficacy.

Computational Scattered Light Imaging represents a paradigm shift in microstructural imaging, transforming ordinary histology slides into rich sources of fiber orientation data through a simple yet powerful physical principle. Its minimal equipment requirements, compatibility with diverse sample types, and ability to resolve complex fiber networks position ComSLI as an accessible yet sophisticated tool for neural pathway research. As adoption grows, ComSLI promises to accelerate discoveries in basic neuroscience, neurodegenerative disease mechanisms, and therapeutic development by making high-resolution fiber mapping available to researchers regardless of their resources or technical specialization. The technique's demonstrated success in revealing previously invisible microstructural alterations in Alzheimer's disease, multiple sclerosis, and other conditions underscores its potential to advance our understanding of brain function and dysfunction at its most fundamental level.

The quest to understand the intricate wiring of the brain requires methods that can provide a comprehensive, high-resolution view of neural circuits within their native, three-dimensional context. Traditional histological techniques, which rely on physical sectioning of tissue, are inherently destructive and prone to introducing errors in the reconstruction of long-range projections and complex cellular relationships. CLARITY (Clear Lipid-exchanged Acrylamide-hybridized Rigid Imaging/Immunostaining/Insitu-hybridization-compatible Tissue-hYdrogel) represents a transformative advance in this field. Developed by the Chung Lab, it is a hydrogel-based tissue clearing method that overcomes these limitations by rendering entire organs, including the brain and spinal cord, optically transparent and macromolecule-permeable while preserving structural and molecular integrity [39] [40]. This technique allows researchers to image intact tissues at high resolution, facilitating detailed interrogation of neural circuits in both health and disease, and is compatible with a wide range of tissues from zebrafish to post-mortem human samples [39] [41]. By enabling the visualization of the "projectome," CLARITY serves as a critical tool within the broader thesis of whole-brain imaging, bridging the gap between cellular-level detail and system-level circuit mapping.

Principles of CLARITY

The core innovation of CLARITY lies in its ability to separate lipids, which are the primary source of light scattering in tissue, from the structural and molecular components of interest, such as proteins and nucleic acids. This is achieved through a process of hydrogel-tissue hybridization [39] [40].

In this process, a hydrogel solution—composed of acrylamide monomers, a thermal initiator, and formaldehyde—is perfused into the fixed tissue. The monomers infiltrate the tissue and, upon polymerization, form a porous mesh that covalently binds to and encapsulates biomolecules like proteins and nucleic acids. This creates a hybrid structure where the endogenous biomolecules are anchored to a stable, external scaffold.

The lipid membranes, which are not incorporated into this hydrogel network, are then removed through a process called delipidation. This is typically accomplished by perfusing the tissue with a strong ionic detergent, such as Sodium Dodecyl Sulfate (SDS). The removal of lipids eliminates the major barrier to light penetration and antibody diffusion, resulting in a transparent, nanoporous sample that retains its original architecture and is accessible to large molecular probes like antibodies [39] [40]. The resulting cleared tissue is both optically transparent and structurally intact, enabling deep-tissue imaging and multiplexed molecular labeling in three dimensions.

Application Notes and Protocols

CLARITY has been successfully adapted for use across a wide variety of species and tissue types, from whole zebrafish and mouse brains to human clinical samples [41]. The following section outlines the primary protocol and key variations.

Core CLARITY Workflow

The diagram below illustrates the primary workflow for the Passive CLARITY Technique (PACT), a common and accessible variation of the method.

Detailed Experimental Protocol

Hydrogel Monomer Solution (prepare fresh and keep ice-cold):

- UltraPure water: 26 mL

- 40% Acrylamide solution: 4 mL

- 10X PBS: 4 mL

- 32% PFA: 5 mL

- Initiator solution (e.g., VA-044, 10% stock): 1 mL

- Note: Always add reagents in the specified order. The solution can be stored at -20°C for future use.

Delipidation/ Clearing Buffer (pH 8.5):

- SDS: 200 mM

- Boric Acid: Adjust to pH 8.5

- Lithium hydroxide monohydrate: 20 mM

Refractive Index Matching Solution (RIMS):

- N-methyl-D-glucamine: 23.5% (w/v)

- Diatrizoic acid: 29.4% (w/v)