Validating Neuroplasticity Markers Across Species: Bridging the Translational Gap for Drug Development

This article provides a comprehensive roadmap for the validation of neuroplasticity markers across different species, a critical step in translating preclinical findings into effective human therapeutics.

Validating Neuroplasticity Markers Across Species: Bridging the Translational Gap for Drug Development

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive roadmap for the validation of neuroplasticity markers across different species, a critical step in translating preclinical findings into effective human therapeutics. Aimed at researchers and drug development professionals, it explores the fundamental molecular mechanisms of neuroplasticity, evaluates advanced measurement techniques from animal models to human applications, addresses key challenges in cross-species comparison, and establishes robust validation frameworks. By synthesizing current research and emerging methodologies, this work aims to enhance the predictive validity of neuroplasticity biomarkers, ultimately accelerating the development of novel treatments for neurological and psychiatric disorders.

Core Mechanisms of Neuroplasticity: From Molecules to Neural Circuits

Neuroplasticity, a fundamental property of the nervous system, refers to the brain's remarkable capacity to adapt its structure and function in response to experience, environmental demands, and injury throughout the lifespan. This dynamic process encompasses a spectrum of mechanisms ranging from molecular and cellular changes to large-scale network reorganization [1] [2]. Once believed to be a static organ after critical developmental periods, the brain is now recognized as highly malleable, continuously refining its circuits through mechanisms including synaptic strengthening and weakening, axonal sprouting, cortical remapping, and in specific regions, the generation of new neurons (adult neurogenesis) [3] [4].

Understanding neuroplasticity is paramount for developing novel therapeutic interventions for neurological and psychiatric disorders. Research has established that impaired neuroplasticity constitutes a core pathophysiological mechanism in conditions such as depression, stroke, and Alzheimer's disease [1] [5]. Conversely, interventions that harness or enhance neuroplasticity—including rehabilitation, pharmacotherapy, and targeted cognitive training—hold promise for facilitating functional recovery. This review objectively compares key manifestations of neuroplasticity across different experimental contexts and species, providing a critical analysis of the supporting data and methodologies that underpin our current understanding.

Comparative Analysis of Neuroplasticity Manifestations

The following tables summarize quantitative findings and characteristics of neuroplasticity across various research domains, highlighting both the diversity and common principles of neural adaptation.

Table 1: Software Variability in Quantifying Hippocampal Volume – A Critical Comparison

| Software Application | Left Hippocampus Mean Difference (mm³) | Right Hippocampus Mean Difference (mm³) | Intraclass Correlation (ICC) | Key Finding |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| FreeSurfer (FS) | -209 | -232 | 0.88 (LH), 0.86 (RH) | Showed highest consistency vs. mean of all methods [6] |

| SPM-Neuromorphometrics | -820 | -745 | Data Not Provided | Moderate agreement [6] |

| SPM-Hammers | -1474 | -1547 | Data Not Provided | Low agreement [6] |

| Quantib | -680 | -723 | 0.36 (RH) | Low agreement, particularly for right hippocampus [6] |

| GIF | 891 | 982 | Data Not Provided | Moderate agreement [6] |

| STEPS | 2218 | 2188 | 0.42 (LH) | Lowest agreement vs. mean of all methods [6] |

Table 2: Occupational Neuroplasticity – Meta-Analysis Findings from Expert vs. Novice Studies

| Brain Metric | Brain Region | Expert vs. Novice Difference | Proposed Functional Correlation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Functional Activation | Left Precentral Gyrus (BA6) | Stronger activation in experts | Motor planning and execution [2] |

| Functional Activation | Left Middle Frontal Gyrus (BA6) | Stronger activation in experts | Cognitive control and motor learning [2] |

| Functional Activation | Right Inferior Frontal Gyrus (BA9) | Stronger activation in experts | Complex cognitive processing [2] |

| Gray Matter Volume | Bilateral Superior Temporal Gyrus (BA22) | Greater volume in experts | Auditory processing and integration [2] |

| Gray Matter Volume | Right Putamen | Greater volume in experts | Motor skill automatization and learning [2] |

Table 3: Interspecies Comparison of Key Neuroplasticity Features

| Feature | Rodents (e.g., Mice/Rats) | Non-Human Primates | Humans |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hippocampal Neurogenesis Rate | High and relatively stable in adulthood [4] | Sharply decreases after juvenile stage; 10x lower than rodents [4] | Persistent through life, but rate is debated; steep decline after childhood reported [4] |

| Neuronal Maturation Rate | Faster maturation rate [4] | Protracted maturation, longer functional window [4] | Slow maturation, similar to primates [4] |

| Subventricular Zone-Olfactory Bulb Neurogenesis | Robust, with a clear rostral migratory stream [3] [4] | Reduced compared to rodents [4] | Highly controversial; likely present in children but rare/absent in adults [4] |

| Cortical Immature Neurons (cINs) | Present, but drop rapidly with age [3] | Data Not Provided | More abundant and widespread in gyrencephalic species; maintained at advanced ages [3] |

Key Experimental Protocols in Neuroplasticity Research

Volumetric MRI Analysis for Hippocampal Atrophy

Objective: To quantify the agreement and variability across different automated software applications for measuring hippocampal volume, a key biomarker in conditions like Alzheimer's disease [6].

Methodology:

- Population: A clinically relevant sample is selected, typically including both patients with confirmed hippocampal atrophy (e.g., Alzheimer's dementia) and age-/gender-matched healthy controls [6].

- MRI Acquisition: High-resolution isovoxel T1-weighted magnetization-prepared rapid gradient-echo (MPRAGE) sequences are acquired using a 3 Tesla MRI scanner to ensure consistent image quality [6].

- Software Processing: The same MRI datasets are processed through multiple, well-established volumetric software packages. In a seminal study, these included FreeSurfer (FS), Statistical Parametric Mapping (SPM) using two different atlases (Neuromorphometrics and Hammers), Geodesic Information Flows (GIF), Similarity-and-Truth-Estimation-for-Propagated-Segmentations (STEPS), and the commercial platform Quantib [6].

- Statistical Analysis: Agreement is assessed by:

- Comparing categorization of volumes into quartiles.

- Calculating Intraclass Correlation Coefficients (ICCs) between each method and the mean of all methods.

- Employing Bland-Altman statistics to visualize the amount of disagreement across the data spread [6].

Key Data Output: Hippocampal volume in mm³ for each subject from each software, allowing for direct comparison of absolute values and inter-method reliability [6].

EEG as a Biomarker for Rehabilitation-Induced Neuroplasticity

Objective: To identify neuroplasticity changes via electroencephalogram (EEG) signals and associate them with functional improvements during post-stroke gait rehabilitation, comparing different therapy frequencies [7].

Methodology:

- Study Design: A randomized, single-blinded, controlled trial among subacute stroke individuals.

- Intervention: Participants are randomized into an Intervention Group (IG) receiving high-frequency gait training (3 times/week) and a Control Group (CG) receiving low-frequency training (once/week) for 12 weeks. Training includes strengthening, balance, and gait exercises [7].

- Outcome Measures:

- Functional Measures: Assessed at pre- (R0) and post-intervention (R1), including the 6-Minute Walk Test (6MWT), Motor Assessment Scale (MAS), Berg Balance Scale (BBS), and Modified Barthel Index (MBI) [7].

- EEG Measures: Resting-state EEG is recorded at R0 and R1 using a 32-electrode cap. Key quantitative indices are derived:

- Delta to Alpha Ratio (DAR)

- Delta+Theta to Alpha+Beta Ratio (DTABR) [7].

- Statistical Analysis: Changes in functional and EEG measures are calculated. The core analysis investigates the association between the change in EEG indices (DAR, DTABR) and the change in functional scores, with the hypothesis that correlations will be stronger in the high-frequency IG [7].

Key Data Output: Correlation coefficients demonstrating the relationship between neurophysiological changes (EEG indices) and functional recovery, providing an objective measure of a dose-response relationship in neuroplasticity [7].

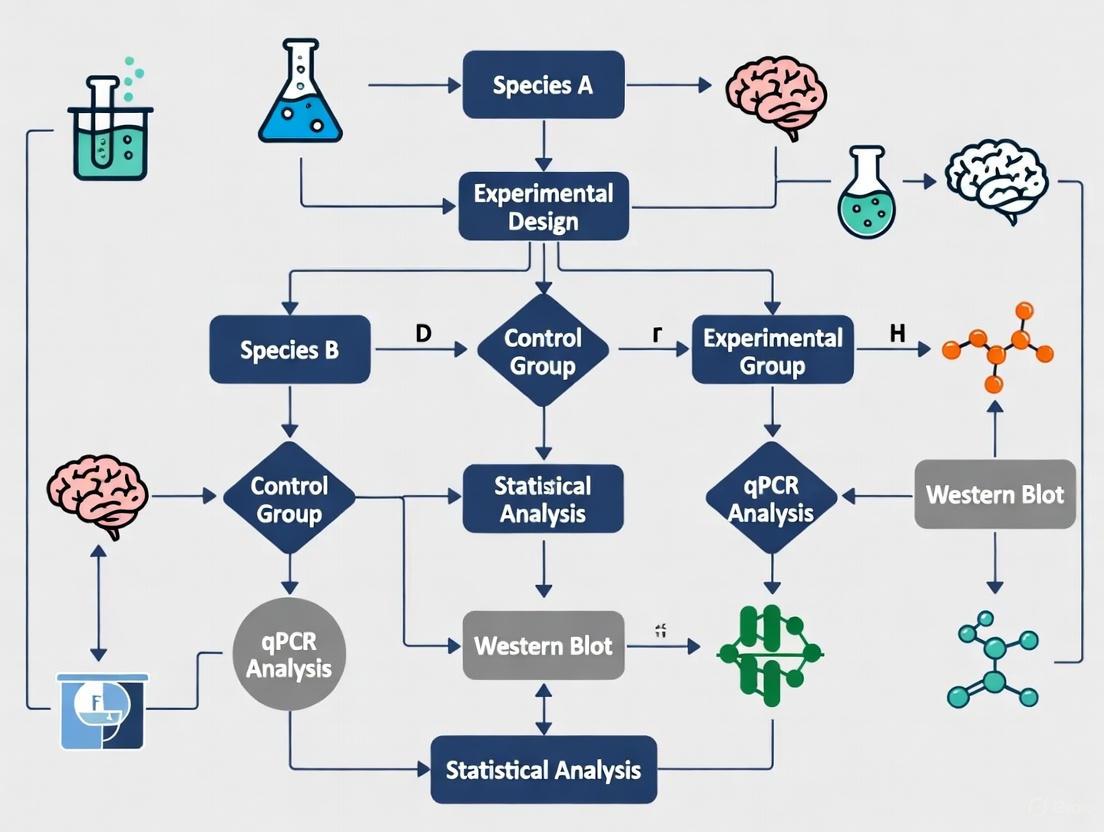

Signaling Pathways and Neuroplasticity Workflows

The following diagrams illustrate key molecular pathways and experimental designs relevant to neuroplasticity research.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 4: Essential Reagents and Tools for Neuroplasticity Research

| Research Tool / Reagent | Primary Function in Neuroplasticity Research | Example Application |

|---|---|---|

| BrdU (Bromodeoxyuridine) | Thymidine analog that incorporates into DNA during synthesis; labels dividing cells for birth-dating and tracking new neuron survival and integration [4]. | Validating adult neurogenesis in post-mortem human hippocampal tissue [4]. |

| DCX (Doublecortin) Antibody | Immunohistochemical marker for immature and migrating neurons; used to identify and quantify neuroblasts and young neurons [3] [4]. | Detecting newly generated neurons in the dentate gyrus; caution required as it may also label non-newly born "dormant" neurons in some contexts [3]. |

| PSA-NCAM Antibody | Marker for polysialylated neural cell adhesion molecule, expressed on immature neurons with high synaptic plasticity; indicates structural remodeling [4]. | Studying neuronal maturation and synaptic reorganization in the post-stroke brain [4]. |

| BDNF ELISA Kits | Quantify levels of Brain-Derived Neurotrophic Factor (BDNF), a key protein supporting neuronal survival, differentiation, and synaptic plasticity [1]. | Measuring BDNF changes in serum or post-mortem brain tissue in depression models and after antidepressant treatments like ketamine [1]. |

| qEEG Analysis Software | Computes quantitative indices from electroencephalogram (EEG) data, such as Delta/Alpha Ratio (DAR), to serve as non-invasive biomarkers of brain state and plasticity [7]. | Objectively monitoring neuroplasticity changes in response to rehabilitation frequency in stroke patients [7]. |

| Volumetric MRI Software (e.g., FreeSurfer) | Automated segmentation and quantification of brain structure volumes (e.g., hippocampus) from MRI scans to assess atrophy or growth [6]. | Tracking disease progression in Alzheimer's or measuring experience-dependent structural changes in experts like taxi drivers [6] [2]. |

The comparative data presented herein underscores that neuroplasticity is not a single, universally conserved process but a multifaceted tool used differently across species, brain regions, and experimental contexts. The stark differences in hippocampal volumetry between software platforms highlight a critical methodological challenge: the lack of a gold standard can impede the translation of research findings into clinical practice [6]. Similarly, the interspecies variations in neurogenesis rates and persistence demand careful consideration when extrapolating mechanistic insights from rodent models to human patients [3] [4].

Promisingly, convergent evidence from molecular, structural, and functional studies is weaving a coherent narrative. The rapid synaptogenesis induced by ketamine in rodent models provides a plausible biological substrate for its clinical effects, bridging molecular plasticity with system-level recovery [1]. Furthermore, the application of accessible technologies like qEEG to objectively measure neuroplasticity in response to rehabilitation dose offers a path toward more personalized and effective therapeutic regimens [7]. Future research must continue to leverage multi-modal approaches and cross-species comparative studies to validate robust biomarkers of neuroplasticity, ultimately accelerating the development of interventions that effectively harness the brain's innate capacity for change.

This guide provides a comparative analysis of three central molecular systems governing neuroplasticity: Brain-Derived Neurotrophic Factor (BDNF), Polysialylated Neural Cell Adhesion Molecule (PSA-NCAM), and Glutamate Receptors. The dynamic interplay between these molecules regulates synaptic strength, structural remodeling, and cognitive functions. Understanding their coordinated actions is crucial for validating neuroplasticity markers across species and developing targeted therapeutic interventions for neurological and psychiatric disorders. The following sections synthesize experimental data, methodologies, and key research tools to objectively compare their functions, interactions, and translational relevance.

Molecular and Functional Profiles

The table below summarizes the core characteristics, primary functions, and experimental readouts for BDNF, PSA-NCAM, and glutamate receptors.

Table 1: Comparative Molecular Profiles of Key Neuroplasticity Players

| Molecular Player | Primary Isoforms/Subtypes | Core Function in Neuroplasticity | Key Experimental Readouts |

|---|---|---|---|

| BDNF | proBDNF, mature BDNF [8] | Enhances excitatory synaptic transmission; promotes dendritic growth & spine formation [8] [9] | Increased mEPSC frequency/amplitude [10]; CREB phosphorylation [9] |

| PSA-NCAM | NCAM-120, NCAM-140, NCAM-180 (all can be polysialylated) [11] | Reduces cell adhesion, facilitates structural plasticity & synaptic remodeling [11] [12] | Expression levels (Western blot); LTP/LTD impairment after enzymatic removal [11] |

| Glutamate Receptors | NMDA, AMPA, Kainate [11] [13] | Mediate fast excitatory transmission; NMDA-R crucial for synaptic calcium signaling & LTP [11] [9] | Receptor phosphorylation [9]; single-channel open probability [9]; synaptic current kinetics [10] |

Quantitative Comparison of Plasticity Effects

Direct experimental data from model systems highlight the quantifiable impact of each molecule on synaptic form and function.

Table 2: Experimental Data on Synaptic and Structural Effects

| Parameter Measured | Experimental System | BDNF Effect | PSA-NCAM Effect | Glutamate Receptor (NMDA) Effect |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Excitatory Synaptic Current Frequency | Cultured hippocampal neurons (rodent) | Increased from ~0.9 Hz to ~2.2 Hz after long-term BDNF [10] | Modulates signaling; indirect effect on network activity [11] | Not Applicable (Directly mediates currents) |

| Excitatory Synaptic Current Amplitude | Cultured hippocampal neurons (rodent) | Increased from ~74 pA to ~146 pA after long-term BDNF [10] | PSA potentiates AMPA receptor currents [11] | Not Applicable (Directly mediates currents) |

| Impact on LTP/LTD | CA3-CA1 synapses (rodent) | Facilitates LTP induction [8] [14] | Ablation of polysialyltransferases impairs LTP and LTD [11] | Directly required for LTP induction |

| Dendritic Growth/Complexity | Cortical neurons (rodent) | Promotes dendritic arbor development [9] | Promotes axonal branching & outgrowth during development [11] [12] | NMDA-R activation is essential for BDNF-induced growth [9] |

Experimental Protocols for Key Assays

Protocol: Assessing BDNF's Impact on Synaptic Transmission

This electrophysiology protocol is used to quantify BDNF-induced changes in synaptic strength [10].

- Primary Neuron Culture: Prepare dissociated hippocampal cultures from postnatal day 1-2 rodents.

- Treatment: Apply mature BDNF (e.g., 20 nM) to the culture medium for a defined period (24 hours to 4 days for chronic effects). Include control cultures without BDNF.

- Electrophysiological Recording: Use whole-cell patch-clamp recordings at a holding potential of -70 mV. Record spontaneous postsynaptic currents (PSCs).

- Pharmacological Isolation: To isolate specific currents:

- Data Analysis: Analyze recorded traces for frequency (number of events per second) and amplitude (peak current in pA) of PSCs. Compare BDNF-treated and control groups.

Protocol: Localizing Endogenous BDNF at Synapses

This super-resolution microscopy protocol determines the precise synaptic localization of BDNF [14].

- Sample Preparation: Use long-term cultured hippocampal neurons (>21 days in vitro) to ensure mature synapses.

- Fixation and Immunostaining: Fix neurons and perform immunofluorescence using rigorously validated anti-BDNF antibodies. Co-stain for pre- and postsynaptic markers (e.g., Bassoon for presynapse, Homer for postsynapse).

- Super-Resolution Imaging: Perform direct Stochastic Optical Reconstruction Microscopy (dSTORM). Acquire two-color dSTORM images with a spatial resolution of ~20 nm.

- Image Analysis: Quantify the localization of BDNF immuno-signals relative to the synaptic scaffold proteins. BDNF signals appear as ~60 nm granules, with the vast majority found within the presynaptic compartment [14].

Signaling Pathways and Molecular Interactions

The following diagrams illustrate the core interactions and experimental workflows involving BDNF, PSA-NCAM, and glutamate receptors.

Cooperative BDNF-Glutamate Signaling in Dendritic Development

PSA-NCAM Modulation of Synaptic Signaling

Workflow: Integrated Neuroplasticity Marker Validation

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

This table catalogs critical reagents for investigating these neuroplasticity markers, with applications spanning molecular, cellular, and functional analyses.

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Neuroplasticity Research

| Reagent / Tool | Function / Application | Example Use-Case |

|---|---|---|

| Recombinant Mature BDNF | Activate TrkB signaling; acute or chronic treatment of neuronal cultures [10] | Studying enhancement of excitatory synaptic transmission (mEPSCs) [10] |

| Endoneuraminidase (EndoN) | Enzymatically digest polysialic acid (PSA) from NCAM [11] | Probing functional role of PSA-NCAM in LTP, learning, and memory [11] |

| Phospho-Specific Antibodies | Detect phosphorylation of CREB, NR1, NR2B subunits [9] | Mapping activation of BDNF and glutamate receptor signaling pathways [9] |

| Validated Anti-BDNF Antibodies | Detect endogenous BDNF for imaging (e.g., dSTORM) and Western blot [14] | Precise sub-synaptic localization of native BDNF protein [14] |

| GAP-43 Antibodies / Assays | Monitor neuronal growth and plasticity; readout of BDNF/AMPA-R signaling [13] | Assessing neurotrophic effects and neuronal remodeling [13] |

| Positive AMPA Receptor Modulators | Allosterically potentiate AMPA receptor function [13] | Elevating endogenous BDNF & GAP-43 levels as a neuroprotective strategy [13] |

| Lentiviral Vectors (e.g., Cre, shRNA) | Genetic manipulation (knockdown, overexpression) in primary neurons [14] | Cell-type specific or conditional gene manipulation (e.g., BDNF deletion) [14] |

Cross-Species Validation and Biomarker Potential

Translating findings from model systems to humans requires cross-species validation. Serum biomarkers like GDF-10 and uPAR, which are involved in axonal sprouting and tissue remodeling, show promise for monitoring recovery in stroke patients undergoing rehabilitation [5]. The BRAIN Initiative emphasizes integrating molecular, structural, and functional data across species to establish robust, clinically relevant markers of brain health and disease [15]. The cooperative mechanisms between BDNF, PSA-NCAM, and glutamate receptors are evolutionarily conserved, making them central targets for this validation pipeline and for the development of novel therapeutics for neuropsychiatric and neurodegenerative disorders.

Synaptic plasticity, the ability of synapses to strengthen or weaken over time in response to increases or decreases in their activity, is fundamental to brain function. Long-term potentiation (LTP) and long-term depression (LTD) represent two primary forms of sustained synaptic plasticity that work in concert to refine neural circuits, enabling learning, memory, and cognitive flexibility [16]. These processes operate as complementary forces—the yin and yang of synaptic plasticity—maintaining homeostasis while allowing experience-dependent adaptation. Beyond their physiological roles, understanding the precise molecular mechanisms of LTP and LTD has become crucial for validating neuroplasticity markers across species, particularly in preclinical drug development for neurological and psychiatric disorders. This guide provides a comprehensive comparison of LTP and LTD mechanisms, their molecular correlates, and the experimental approaches used to study them across different model systems.

Core Mechanisms: A Comparative Analysis of LTP and LTD

Induction and Expression Mechanisms

The induction of LTP and LTD hinges on specific patterns of neural activity and subsequent calcium signaling that determine the direction of synaptic change. N-methyl-D-aspartate receptors (NMDARs) serve as the critical coincidence detectors in both processes, with their voltage-dependent magnesium block providing the molecular basis for Hebbian plasticity [17] [18].

Table 1: Comparative Induction Mechanisms of LTP and LTD

| Feature | Long-Term Potentiation (LTP) | Long-Term Depression (LTD) |

|---|---|---|

| Stimulation Pattern | High-frequency stimulation (e.g., 100 Hz) | Low-frequency stimulation (e.g., 1 Hz for 10-15 min) [16] |

| NMDA Receptor Activation | Strong depolarization removes Mg²⁺ block, allowing substantial Ca²⁺ influx [17] | Partial depolarization permits moderate Ca²⁺ influx through NMDA receptors [16] |

| Calcium Dynamics | Large, rapid increase in postsynaptic Ca²⁺ | Modest, sustained increase in postsynaptic Ca²⁺ [16] |

| Downstream Signaling | Activation of calcium/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II (CaMKII), protein kinases [19] | Activation of protein phosphatases (PP1, PP2A, calcineurin) [16] |

| AMPAR Trafficking | Synaptic insertion of GluA1/GluA2-containing AMPARs [19] | Internalization of GluA2-containing AMPARs from postsynaptic membrane [19] |

Table 2: Expression Profiles of LTP and LTD

| Characteristic | LTP | LTD |

|---|---|---|

| Presynaptic Changes | Increased neurotransmitter release probability; redistribution of synaptophysin [20] | Minimal change in release probability [20] |

| Postsynaptic Changes | Increased AMPAR number and conductance; spine enlargement [16] | Decreased AMPAR number and conductance; spine shrinkage [16] |

| Structural Plasticity | Increased spine head size; stabilization of synapses [16] | Reduced spine size; potential synapse elimination [16] |

| Temporal Duration | Hours to lifetime of organism [16] | Hours to days [16] |

| Computational Role | Information storage; memory formation [16] [19] | Circuit refinement; memory updating; homeostasis [16] |

Molecular Correlates and Signaling Pathways

The distinct calcium dynamics triggered by LTP and LTD induction protocols activate different enzymatic cascades that ultimately determine the direction of synaptic change. LTP-inducing stimuli generate a large, rapid calcium rise that preferentially activates calcium/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II (CaMKII) and protein kinase C (PKC), leading to phosphorylation of existing AMPARs and promotion of synaptic delivery of new receptors [19]. In contrast, the modest calcium elevation during LTD induction activates calcium-sensitive phosphatases such as calcineurin, which dephosphorylate AMPARs and facilitate their clathrin-mediated endocytosis [16] [19].

The following diagram illustrates the key molecular pathways involved in LTP and LTD:

Molecular Signaling in LTP and LTD

Experimental Methodologies Across Species

Electrophysiological Approaches

Electrophysiological recording techniques remain the gold standard for investigating synaptic plasticity across species. These approaches enable precise quantification of changes in synaptic strength following specific induction protocols.

Table 3: Electrophysiological Protocols for Inducing Plasticity

| Method | Protocol Details | Typical Preparation | Measured Output |

|---|---|---|---|

| High-Frequency Stimulation (LTP) | 100 Hz, 1 sec tetanus; or theta-burst stimulation (5 bursts of 4 pulses at 100 Hz, separated by 200 ms) [16] | Rodent hippocampal slices; anesthetized or freely moving rodents | Sustained increase in field excitatory postsynaptic potential (fEPSP) slope or population spike amplitude |

| Low-Frequency Stimulation (LTD) | 1 Hz stimulation for 10-15 minutes [16] | Rodent hippocampal or cortical slices; anesthetized rodents | Sustained decrease in fEPSP slope or amplitude |

| Spike-timing-dependent plasticity (STDP) | Repeated presynaptic activation followed by postsynaptic spiking within precise time windows (typically ±20 ms) | Cortical or hippocampal cultures or slices | Timing-dependent LTP or LTD |

| Chemically-induced LTP/LTD | Application of NMDA or DHPG (mGluR agonist) to induce chemical LTD [20] | Acute brain slices | Receptor-specific plasticity without electrical stimulation |

Translational Approaches in Humans

Non-invasive electroencephalography (EEG) recordings of visually evoked potentials (VEPs) have emerged as promising translational biomarkers for assessing LTP-like plasticity in humans. Different modulation protocols induce plasticity with distinct temporal profiles, enabling researchers to select paradigms based on experimental objectives [21].

Table 4: VEP-Based Plasticity Protocols in Humans

| Modulation Protocol | Stimulation Parameters | Plasticity Time Course | Best Suited For |

|---|---|---|---|

| Low-Frequency Stimulation | 10 min at 2 reversals per second (rps) [21] | Transient changes peaking at 2 min, dissipating within 12 min [21] | Brief plasticity assessments; drug screening |

| Repeated Low-Frequency | Three 10 min blocks at 2 rps [21] | Sustained changes persisting up to 22 min [21] | Longer-lasting plasticity evaluation |

| High-Frequency Stimulation | 9 Hz tetanic modulation [21] | Sharp but brief increases in plasticity [21] | Acute potentiation studies |

| Theta-Pulse Stimulation | Theta-frequency pattern stimulation [21] | Moderate but prolonged changes lasting up to 28 min [21] | Stable, sustained plasticity measures |

The following diagram illustrates a typical experimental workflow for VEP-based plasticity assessment in humans:

VEP Plasticity Assessment Workflow

Neuroplasticity Markers in Health and Disease

Molecular Markers of Synaptic Plasticity

Specific proteins serve as key markers for tracking synaptic plasticity changes in both experimental models and human studies. These markers can be categorized into presynaptic, postsynaptic, and glial components, each providing different insights into plasticity mechanisms.

Table 5: Key Molecular Markers of Synaptic Plasticity

| Marker Category | Specific Markers | Association with Plasticity | Detection Methods |

|---|---|---|---|

| Presynaptic Markers | Synaptophysin (decreased after LTP) [20] | Vesicle recycling and neurotransmitter release | Immunogold EM, immunohistochemistry, Western blot |

| Postsynaptic Receptors | Phospho-GluA1 (Ser831), GluA2 internalization [19] | AMPAR trafficking during LTP/LTD | Phospho-specific antibodies, surface biotinylation |

| Scaffolding Proteins | PSD-95, Homer, Shank | Postsynaptic density organization | Immunohistochemistry, proteomics |

| Calcium Signaling | CaMKII, calcineurin | Plasticity direction determination | Activity assays, phospho-proteomics |

| Structural Markers | Dendritic spine morphology (head size, neck length) | Structural correlates of functional changes | Two-photon imaging, electron microscopy |

Dysregulated Plasticity in Disease States

Alterations in LTP and LTD mechanisms underlie various neurological and psychiatric disorders, providing valuable targets for therapeutic intervention. Recent research has identified specific plasticity deficits across different conditions.

In Alzheimer's disease (AD), amyloid-β (Aβ) oligomers drive excessive internalization of GluA2-containing AMPARs, leading to synaptic depression and cognitive impairment [19]. Transgenic mouse models expressing familial AD mutations show normal engram formation but failed memory retrieval, with optogenetic reactivation of engram neurons rescuing memory deficits—indicating that storage remains intact while access is impaired [19]. Similarly, major depressive disorder, bipolar disorder, and schizophrenia demonstrate impaired VEP-related plasticity, while antidepressant interventions including selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors and ketamine enhance plasticity measures in these paradigms [21].

The diagram below illustrates how AMPAR trafficking disruptions contribute to synaptic deficits in Alzheimer's disease models:

AMPAR Trafficking in Alzheimer's Models

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 6: Key Research Reagents for Synaptic Plasticity Studies

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Research Application | Key Findings Enabled |

|---|---|---|---|

| Transgenic Mouse Models | Drd1a-TdTomato/Drd2-EGFP mice [22]; APP/PS1 mice [19] | Cell-type-specific plasticity; disease modeling | Revealed opposing roles of D1/D2 neurons in reward; identified Aβ-induced AMPAR trafficking defects |

| Viral Vectors | AAV-RAM-d2TTA::TRE-EGFP (engram labeling) [19] | Targeted neuronal population labeling | Enabled identification and manipulation of engram ensembles |

| Activity Reporters | c-Fos, SomaGCaMP7 [19] | Neural activity mapping | Identified reward-responsive neuronal populations |

| Receptor Antagonists | NMDA receptor antagonists (AP5, MK-801) | Pathway blockade | Established NMDAR necessity for LTP induction and memory |

| Kinase/Phosphatase Modulators | CaMKII inhibitors; phosphatase inhibitors | Signaling pathway manipulation | Determined necessity of specific enzymes for plasticity |

| AMPAR Trafficking Tools | GluA2 cytoplasmic tail peptides [19] | Interference with specific AMPAR interactions | Demonstrated role of GluA2 endocytosis in LTD and memory silencing |

Cross-Species Validation of Neuroplasticity Markers

The translation of synaptic plasticity findings across species requires careful validation of conserved mechanisms and markers. Several key approaches have emerged to bridge this translational gap:

Electrophysiological Correlates: The preservation of NMDAR-dependent LTP and LTD mechanisms from rodents to humans provides a fundamental basis for cross-species comparison. While induction protocols may vary, the core molecular machinery involving NMDAR activation, calcium signaling, and AMPAR trafficking remains largely conserved [16] [21].

Imaging Biomarkers: VEP-based plasticity measures in humans share key properties with cellular LTP, including NMDAR dependency, input specificity, and persistence [21]. These non-invasive paradigms enable direct comparison with slice electrophysiology and in vivo animal studies, facilitating biomarker validation for drug development.

Molecular Conservation: Key molecular markers such as phospho-GluA1, synaptophysin, and PSD-95 show conserved roles in synaptic plasticity across species [19] [20]. This molecular conservation enables the use of these markers as translational endpoints in preclinical to clinical research.

Behavioral Correlates: Plasticity measures across species correlate with cognitive functions, particularly memory performance [21] [23]. The inverted U-shape association between second language engagement and hippocampal gray matter volume in bilingual young adults demonstrates experience-dependent structural plasticity that mirrors functional plasticity observed in animal models [23].

The consistent findings across molecular, physiological, and behavioral levels provide a robust framework for validating neuroplasticity markers in cross-species research, particularly for developing therapies targeting cognitive dysfunction in neuropsychiatric disorders.

The brain's remarkable capacity to adapt, often termed neuroplasticity, relies heavily on the structural remodeling of neurons, particularly the formation and reorganization of synapses. This review focuses on two core components of this process: dendritic remodeling, the physical reshaping of a neuron's dendritic arbor, and synaptogenesis, the formation of new synapses. Within the context of modern neuroscience research, a critical challenge is the translation of findings from model organisms to humans. This guide objectively compares key experimental models and their outcomes, framing the data within the broader thesis of validating neuroplasticity markers across species. Understanding the strengths and limitations of each model is essential for researchers and drug development professionals aiming to bridge this translational gap.

Table 1: Quantitative Comparisons of Structural Plasticity Findings Across Models

| Experimental Model | Key Structural Finding | Quantitative Change | Technique Used | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rat Hippocampus (LTP) | Increase in small dendritic spines | >3x increase in density of small spines (PSD <0.05 µm²) | 3DEM | [24] |

| Remodeling of shaft Smooth Endoplasmic Reticulum (SER) | Significant decrease in shaft SER volume | 3DEM | [24] | |

| Mouse Orbitofrontal Cortex (Memory Trace) | Spine maturation on Memory Trace (MT) neurons | Higher proportion of mature spine types vs. non-MT neurons | In vivo imaging, chemogenetics | [25] |

| Drosophila LNv Neurons (Sensory Experience) | Dendritic filopodia dynamics | Significant reduction in dynamic branches from 48-72 h AEL to 96-120 h AEL | Time-lapse 3D imaging | [26] |

| Human Audiovisual Association | Cortical thickness & functional connectivity | Increased functional connectivity & cortical thickness in trained right hemisphere | fMRI, cortical thickness analysis | [27] |

Core Mechanisms: Signaling Pathways in Structural Plasticity

Structural plasticity is governed by complex, activity-dependent signaling pathways that converge on the neuronal cytoskeleton. A primary trigger is calcium influx through the NMDA receptor (NMDAR), which activates enzymes like Calcium/Calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II (CaMKII) [28] [29]. This kinase is a central node, implicated in both strengthening synaptic efficacy and stabilizing dendritic arbors. Downstream, the Rho family of GTPases (e.g., Rho, Rac, Cdc42) acts as a master regulator of the actin cytoskeleton, directly controlling the motility of dendritic filopodia, the growth of spines, and their morphological maturation [29] [30].

Recent research has elucidated a local, Golgi apparatus-independent secretory pathway within dendrites that is crucial for supplying membrane and proteins like glutamate receptors during plasticity. As detailed in [24], this pathway involves the smooth endoplasmic reticulum (SER) and recycling endosomes (REs). During Long-Term Potentiation (LTP), the SER provides local membrane resources, and REs are elevated in small spines, facilitating the insertion of AMPA receptors and spine growth [24] [28].

The following diagram illustrates the core signaling pathways and key cellular organelles involved in activity-dependent structural plasticity.

Experimental Models and Methodologies: A Detailed Comparison

A diverse array of experimental models is employed to study structural plasticity, each offering unique advantages and constraints. The choice of model is critical, as it directly influences the translatability of the findings.

Table 2: Comparison of Key Experimental Protocols in Structural Plasticity Research

| Model / Paradigm | Induction Method | Key Measured Output | Temporal Resolution | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rodent Hippocampal LTP (in vitro) | Theta-burst stimulation (TBS) of afferent pathways [24] | Spine density & morphology; SER/endosome volume via 3DEM [24] | Hours post-induction (e.g., 2 hrs) [24] | High cellular resolution; controlled environment | Limited behavioral correlation; acute slice preparation |

| Mouse Motor Skill Learning (in vivo) | Single-pellet reaching task or rotarod training [28] | Spine formation/elimination rate on L5 pyramidal neurons [28] | Days to weeks [28] | Direct link to learning and behavior | Technically challenging; complex data analysis |

| Drosophila LNv Development (ex vivo) | Altered visual sensory experience [26] | Dendritic filopodia dynamics & branch persistence [26] | Minutes to hours (time-lapse) [26] | Powerful genetics; accessible for live imaging | Evolutionary distance from mammals |

| Human Audiovisual Association (in vivo) | Passive exposure to paired auditory/visual stimuli [27] | Resting-state fMRI connectivity & cortical thickness (MRI) [27] | Single session (pre/post) [27] | Direct human data; whole-brain perspective | Indirect measure of synapses; low spatial resolution |

Cross-Species Validation and Technical Challenges

A critical consideration in this field is the significant interspecies variation in plastic processes. For instance, the genesis of new neurons (adult neurogenesis) is widespread and lifelong in fish but quite reduced in both its spatial extent and duration in mammals [3]. Even between mice and humans, there are remarkable differences; neurogenic activity in the lateral ventricle drops sharply by two years of age in humans but persists at high rates in aging mice [3]. This highlights that plasticity is not a uniform brain function but a biological tool that has been adapted for different functions across species.

Technical challenges further complicate cross-species comparisons. A key pitfall is the misinterpretation of cellular markers. For example, the protein doublecortin (DCX) is widely used as a marker for newborn neurons in neurogenic niches. However, DCX-positive neurons in the cerebral cortex layer II are often not newly born but are "dormant" immature neurons that persist post-development [3] [31]. This makes it crucial to pair immaturity markers with cell division markers (e.g., Ki67, BrdU) for conclusive results. Furthermore, the widespread proliferation of oligodendrocyte progenitor cells (OPCs) in the adult brain parenchyma can be a confounding element when quantifying cell proliferation, as OPCs are the major dividing cell population outside of neurogenic zones [3].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

The following table details key reagents and tools essential for conducting research in dendritic remodeling and synaptogenesis.

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Structural Plasticity Studies

| Reagent / Tool | Function / Application | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Fos2A-iCreER Mice | Genetic access to neurons active during a specific time window (memory trace ensembles) [25] | Labeling and chemogenetic manipulation of orbitofrontal cortex neurons active during memory encoding [25]. |

| DREADDs (Gi/Gq) | Chemogenetic silencing (Gi) or activation (Gq) of specific neuronal populations [25] | Testing necessity and sufficiency of memory trace neurons for flexible behavior [25]. |

| Serial Section Electron Microscopy (3DEM) | High-resolution 3D reconstruction of subcellular organelles (SER, endosomes, spines) [24] | Quantifying changes in SER volume and spine morphology following LTP induction [24]. |

| Two-Photon Microscopy | In vivo or ex vivo high-resolution time-lapse imaging of dendritic structures [28] [26] | Tracking the formation and elimination of dendritic spines over days during motor learning [28] [26]. |

| DCX, Ki67, BrdU | Immunohistochemical markers for neuronal immaturity (DCX) and cell proliferation (Ki67, BrdU) [3] | Identifying and quantifying adult-born neurons; requires combinatorial use for specificity [3]. |

| snRNA-seq | Single-nucleus RNA sequencing to profile transcriptomes of individual cells from postmortem tissue [31] | Identifying novel gene expression signatures of neuronal senescence (neurescence) in human brain [31]. |

The objective comparison of experimental data reveals both conserved principles and critical differences in structural plasticity across species. Core mechanisms, such as the role of NMDAR-CaMKII signaling and actin cytoskeleton remodeling, appear widely conserved from Drosophila to mammals [29] [26]. However, the rates, spatial extent, and lifelong persistence of plastic processes like synaptogenesis and adult neurogenesis show significant adaptive variation [3]. For drug development professionals, this underscores the importance of a multi-species, comparative approach. Relying solely on rodent models carries the risk of overlooking human-specific plastic capacities or pathologies. Future research must prioritize the standardization of methods across laboratories and species [3], and the development of more specific, histologically viable markers—such as the paired marker CDKN2D/ETS2 for neuronal senescence [31]—to truly validate the translational potential of neuroplasticity markers for human therapeutic applications.

Neurotrophic signaling pathways are fundamental regulators of neuronal survival, plasticity, and function in the nervous system. The tropomyosin receptor kinase B (TrkB) and p75 neurotrophin receptor (p75NTR) serve as primary receptors for brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) and other neurotrophins, activating divergent downstream signaling cascades that elicit contrasting cellular responses [32] [33]. While these receptors can function independently, emerging evidence indicates they also engage in complex interactions that modulate neuronal fate, synaptic plasticity, and cellular differentiation [34] [35]. Understanding the precise mechanisms of TrkB and p75NTR signaling is crucial for developing targeted therapeutic interventions for neurological disorders, neurodegenerative diseases, and stroke recovery [32] [5] [36].

This review provides a comprehensive comparison of TrkB and p75NTR signaling pathways, focusing on their structural characteristics, downstream effectors, and functional outcomes. We present experimental data from key studies that elucidate the distinct and interactive nature of these receptor systems, with particular emphasis on their roles in cellular survival, apoptosis, and neural circuit modulation. The integration of these findings across multiple experimental models and species provides critical insights for validating neuroplasticity markers and developing novel therapeutic strategies.

Receptor Structures and Ligand Interactions

Structural Characteristics and Binding Properties

TrkB and p75NTR represent distinct classes of neurotrophin receptors with specialized structural features and ligand binding properties. TrkB is a receptor tyrosine kinase that forms dimers upon ligand binding, activating its intracellular kinase domain through autophosphorylation [33]. In contrast, p75NTR belongs to the tumor necrosis factor receptor superfamily and contains a death domain in its cytoplasmic region, enabling it to initiate apoptotic signaling cascades under specific conditions [33].

The ligand affinity and selectivity of these receptors differ significantly. TrkB exhibits high-affinity binding for mature BDNF and NT-4/5, with dissociation constants (Kd) in the nanomolar range [33]. p75NTR serves as a lower-affinity receptor for all neurotrophins, including mature BDNF and its precursor (proBDNF), with binding affinities typically in the nanomolar to micromolar range [37] [33]. This differential binding affinity provides a mechanism for contextual neurotrophin signaling, where the cellular response depends on ligand concentration, receptor expression levels, and the local microenvironment.

Table 1: Structural and Ligand-Binding Properties of TrkB and p75NTR

| Feature | TrkB | p75NTR |

|---|---|---|

| Receptor Type | Tyrosine kinase | TNF receptor superfamily |

| Intracellular Domains | Tyrosine kinase domain | Death domain |

| High-Affinity Ligands | Mature BDNF, NT-4/5 | proBDNF (preferential) |

| Low-Affinity Ligands | NT-3 | All mature neurotrophins |

| Typical Kd Values | ~10⁻¹¹ M (NGF for TrkA) [33] | ~10⁻⁹ M [33] |

| Coreceptor Interactions | p75NTR, Trk isoforms | Trk receptors, sortilin |

Context-Dependent Receptor Interactions

The interaction between TrkB and p75NTR adds considerable complexity to neurotrophin signaling. Research demonstrates that these receptors can form complexes after ligand binding and internalization, particularly in early endosomes of hippocampal neurons [34]. This association occurs following BDNF binding and requires phosphorylation of TrkB, suggesting the complex formation regulates signaling rather than initial ligand binding [34].

The functional outcome of TrkB-p75NTR interactions appears to be context-dependent, influenced by cell type, neurotrophin concentration, and receptor expression ratios. In hippocampal neurons, the association of TrkB with p75NTR is necessary for optimal activation of the PI3K-Akt signaling pathway but not the Erk pathway, indicating selective modulation of downstream signaling branches [34]. This cooperative signaling enhances neuronal survival in trophic deprivation models, highlighting the physiological significance of receptor crosstalk [34].

Downstream Signaling Pathways and Effectors

TrkB-Mediated Survival and Plasticity Pathways

TrkB activation initiates several well-characterized signaling cascades that promote neuronal survival, differentiation, and synaptic plasticity. The primary pathways include:

PI3K-Akt Pathway: BDNF binding to TrkB triggers phosphorylation of specific tyrosine residues in the intracellular domain, creating docking sites for phosphoinositide 3-kinase (PI3K). This leads to Akt activation, which phosphorylates downstream targets including BAD, caspase-9, and transcription factors of the Forkhead family, suppressing apoptotic signals and enhancing cell survival [34] [33].

MAPK/Erk Pathway: TrkB activation also recruits adaptor proteins that activate the Ras-MAPK pathway, culminating in Erk phosphorylation. This pathway regulates gene expression through transcription factors like CREB, influencing neuronal differentiation, synaptic plasticity, and long-term potentiation [34] [37].

PLCγ Pathway: Phospholipase C gamma (PLCγ) binds to phosphorylated TrkB, leading to hydrolysis of phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate (PIP2) into inositol trisphosphate (IP3) and diacylglycerol (DAG). This generates calcium release from intracellular stores and protein kinase C (PKC) activation, modulating synaptic transmission and plasticity [32].

Table 2: Major Downstream Signaling Pathways Activated by TrkB and p75NTR

| Signaling Pathway | Primary Receptor | Key Effectors | Biological Outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|

| PI3K-Akt | TrkB | PI3K, Akt, BAD, GSK-3β | Cell survival, growth, metabolism [34] |

| MAPK/Erk | TrkB | Ras, Raf, MEK, Erk, CREB | Differentiation, plasticity, gene expression [34] [37] |

| PLCγ | TrkB | PLCγ, IP3, DAG, PKC | Synaptic plasticity, calcium signaling [32] |

| NF-κB | p75NTR | IκB kinase, NF-κB | Survival, inflammation (context-dependent) [33] |

| RhoA | p75NTR | Rho GTPase, ROCK | Growth cone collapse, neurite retraction [33] |

| JNK | p75NTR | JNK, c-Jun | Apoptosis, stress response [33] |

p75NTR-Mediated Signaling and Functional Outcomes

p75NTR activates several distinct signaling pathways that can promote either survival or apoptosis depending on cellular context and receptor interactions:

NF-κB Pathway: p75NTR engagement can activate the transcription factor NF-κB through interactions with TRAF family proteins, promoting neuronal survival under specific conditions. This pathway requires cell stress for direct p75NTR-mediated activation and involves complex regulation [33].

RhoA Signaling: p75NTR modulates the activity of RhoA GTPase, which regulates actin cytoskeleton dynamics. This pathway mediates growth cone collapse and inhibits neurite outgrowth, particularly in the presence of myelin-derived inhibitors [33].

JNK Pathway: Through interactions with various adaptor proteins, p75NTR can activate c-Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK), leading to phosphorylation of c-Jun and other transcription factors that promote apoptosis, particularly in the absence of Trk signaling [33].

The functional outcomes of p75NTR signaling are highly context-dependent. In the presence of Trk receptors, p75NTR often enhances neurotrophin binding affinity and specificity, promoting survival signals. However, when expressed alone or during neural injury, p75NTR can initiate apoptotic programs through its death domain and JNK activation [33].

Figure 1: Neurotrophin Signaling Pathways Through TrkB and p75NTR. Mature BDNF primarily activates TrkB receptors, promoting survival and plasticity pathways. proBDNF preferentially binds p75NTR, initiating pathways that can lead to growth cone collapse or apoptosis. Under specific conditions, receptor complexes form, enhancing specific downstream signaling.

Experimental Data and Cross-Species Validation

Quantitative Assessment of Signaling Outcomes

Direct comparison of experimental data reveals the contrasting signaling properties of TrkB and p75NTR pathways. Studies using receptor-specific inhibitors and genetic manipulations have quantified the contributions of these receptors to various cellular processes:

In hippocampal neuron cultures, BDNF treatment (25 ng/mL) induces association between TrkB and full-length p75NTR after ligand binding and receptor internalization [34]. When p75NTR is absent, BDNF-mediated activation of the PI3K-Akt pathway is significantly impaired, while Erk signaling remains largely unaffected, demonstrating pathway-specific modulation [34]. This selective signaling impairment translates to functional deficits, as p75NTR knockout neurons show reduced survival rescue by BDNF in trophic deprivation models [34].

Research on long-term synaptic plasticity demonstrates that BDNF-TrkB signaling promotes slowly developing long-lasting synaptic enhancement (RISE) coupled with synaptogenesis, while proBDNF-p75NTR signaling induces long-lasting synaptic suppression (LOSS) accompanied by synapse elimination [37]. Pharmacological masking of TrkB receptors not only inhibits RISE but converts the response to LOSS, indicating that BDNF can activate p75NTR signaling when TrkB is unavailable [37]. Similarly, masking p75NTR during LTD induction converts synaptic suppression to enhancement, revealing the bidirectional plasticity controlled by these receptor systems.

Table 3: Experimental Evidence for Contrasting TrkB and p75NTR Functions

| Experimental Model | TrkB-Mediated Effects | p75NTR-Mediated Effects | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hippocampal Neurons (Culture) | Promotes survival via PI3K-Akt; BDNF (25 ng/ml) | Necessary for optimal Akt activation; knockout impairs survival | [34] |

| Organotypic Slice Cultures | RISE: synaptic enhancement, synaptogenesis | LOSS: synaptic suppression, elimination | [37] |

| Neural Stem Cells (SVZ) | Low [BDNF] promotes self-renewal via TrkB | High [BDNF] enhances differentiation via p75NTR | [35] |

| Stroke Rehabilitation (Human) | Associated with recovery markers (GDF-10, uPAR) | Potential role in neural repair mechanisms | [5] |

| Inflammation Model (Mice) | BDNF prevents LPS-induced GABAergic marker reduction | Not specifically measured in this study | [38] |

Concentration-Dependent Signaling Effects

The concentration of neurotrophins emerges as a critical factor determining signaling outcomes through TrkB and p75NTR. In adult neural stem cells (NSCs) from the mouse subventricular zone, low BDNF concentrations (primarily activating TrkB) promote self-renewal and proliferation, while higher BDNF concentrations (engaging p75NTR) potentiate TrkB-dependent effects and promote differentiation along the oligodendrocyte lineage [35].

This concentration-dependent effect demonstrates how the same ligand can elicit different cellular responses based on receptor engagement patterns. The use of p75NTR antagonists reduces BDNF-enhanced NSC proliferation and oligodendrocyte commitment, confirming the specific contribution of this receptor to fate determination [35]. These findings have significant implications for therapeutic applications, suggesting that precise control of neurotrophin levels may be necessary to achieve desired outcomes in neural repair strategies.

Methodological Approaches and Research Tools

Key Experimental Protocols

Investigation of TrkB and p75NTR signaling employs specialized methodological approaches that enable precise manipulation and measurement of receptor activities:

Receptor Interaction Studies: The association between TrkB and p75NTR has been demonstrated through immunoprecipitation and FRET analysis in hippocampal neurons [34]. For immunoprecipitation, neurons are treated with BDNF (25 ng/mL) for various durations, lysed with detergent buffers containing protease and phosphatase inhibitors, and subjected to immunoprecipitation with anti-p75NTR antibodies followed by Western blot analysis with TrkB antibodies [34]. Acceptor photobleaching FRET using Alexa 488 (donor) and Alexa 555 (acceptor) fluorophores confirms close proximity between these receptors after BDNF stimulation [34].

Receptor Masking Experiments: Function-blocking antibodies against TrkB and p75NTR have been used to elucidate their respective contributions to synaptic plasticity [37]. In organotypic hippocampal slice cultures, application of TrkB-blocking antibodies after LTP induction converts the expected synaptic enhancement (RISE) to suppression (LOSS), while p75NTR-blocking antibodies during LTD induction convert synaptic suppression to enhancement [37]. These experiments require careful timing of antibody application relative to stimulation protocols to distinguish effects on development versus maintenance of plasticity.

Neural Stem Cell Differentiation Assays: Adult NSCs from mouse SVZ are cultured as neurospheres in DMEM/F12 medium supplemented with B27, glutamax, heparin, EGF (20 ng/mL), and FGF (10 ng/mL) [35]. For differentiation studies, neurospheres are dissociated with accutase and plated at low density (5 cells/μL) in mitogen-completed medium with varying BDNF concentrations. Self-renewal capacity is quantified by counting newly formed neurospheres after 5 days, while differentiation is assessed through immunostaining for lineage-specific markers [35].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 4: Key Research Reagents for Investigating TrkB and p75NTR Signaling

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Research Application | Experimental Function |

|---|---|---|---|

| Receptor Ligands | Recombinant BDNF (25-50 ng/ml) [34] [38] | Survival, plasticity studies | Activates TrkB and p75NTR signaling pathways |

| Function-Blocking Antibodies | Anti-TrkB [37]; Anti-p75NTR (MAB365) [34] [37] | Receptor specificity studies | Blocks specific receptor function to isolate signaling contributions |

| Cell Culture Models | Hippocampal neurons [34]; SVZ NSCs [35]; Organotypic slices [37] | Pathway analysis | Provides physiological context for signaling studies |

| Signaling Inhibitors | PI3K inhibitors (e.g., LY294002); MEK inhibitors (e.g., U0126) | Pathway dissection | Blocks specific downstream signaling branches |

| Detection Methods | Western blot (pAkt, pErk) [34]; FRET [34]; qPCR [38] | Signal measurement | Quantifies pathway activation and receptor interactions |

| Animal Models | p75NTR knockout mice [34]; Conditional TrkB knockouts | In vivo validation | Determines physiological relevance of signaling mechanisms |

Implications for Therapeutic Development

The contrasting signaling properties of TrkB and p75NTR present both challenges and opportunities for therapeutic development. In stroke rehabilitation, biomarkers associated with neurotrophic signaling show promise for monitoring recovery. Serum levels of GDF-10 and uPAR, molecules involved in neuroplasticity, correlate with functional improvements during rehabilitation, suggesting their potential as biomarkers for tracking neurotrophic pathway activation [5]. Specifically, decreased endostatin and increased GDF-10 levels during the first month of rehabilitation associate with greater sensorimotor and functional improvements [5].

For neurodegenerative diseases, the balance between TrkB and p75NTR signaling may influence disease progression. The development of small molecules that selectively activate TrkB while inhibiting p75NTR-mediated apoptotic signaling represents a promising therapeutic strategy [32]. However, delivery challenges remain significant, as neurotrophic factors have limited blood-brain barrier penetration and short half-lives [32]. Innovative approaches including viral vectors, stem cell therapies, and biomaterial-based delivery systems are under investigation to overcome these limitations.

The role of neurotrophic signaling in neuropsychiatric disorders is increasingly recognized. Recent evidence demonstrates that BDNF infusion can prevent LPS-induced reductions in GABAergic interneuron markers (somatostatin, cortistatin, and neuropeptide Y) in mouse hippocampus, suggesting a protective role against inflammation-driven circuitry dysfunction [38]. These findings position BDNF signaling as a potential therapeutic target for conditions involving GABAergic dysfunction, such as schizophrenia and depression.

TrkB and p75NTR receptors mediate contrasting yet complementary signaling pathways that collectively regulate neuronal survival, plasticity, and circuit function. While TrkB primarily activates survival-promoting pathways (PI3K-Akt, MAPK/Erk, PLCγ), p75NTR can initiate both pro-survival and pro-apoptotic signals depending on cellular context and receptor interactions. The formation of TrkB-p75NTR complexes adds regulatory complexity, enabling fine-tuning of downstream signaling responses.

Experimental evidence across multiple models—from cultured neurons to animal studies and human biomarker research—demonstrates the functional significance of these signaling pathways in health and disease. The concentration-dependent effects of neurotrophins, the spatial and temporal regulation of receptor expression, and the balance between mature neurotrophins and their precursors collectively determine cellular outcomes. Future therapeutic strategies targeting neurotrophic signaling must account for this complexity, potentially through receptor-specific approaches or combinatorial treatments that optimize the balance between survival and plasticity signals while minimizing apoptotic activation.

The validation of neurotrophic pathway biomarkers across species strengthens the translational potential of these findings, offering promising avenues for diagnosing neurological conditions, monitoring treatment responses, and developing novel interventions that harness the regenerative capacity of neurotrophic signaling.

Critical Periods and Induced Plasticity (iPlasticity) Across Development

The development of neural circuits is not a static process but is profoundly shaped by experience during specific developmental windows. Critical periods are strictly defined epochs in early postnatal life when the development and maturation of functional properties of the brain are strongly dependent on experience or environmental influences [39]. During these windows, experience instructs neural networks to develop into a specific configuration that cannot be replaced by alternative connectivity patterns, leading to irreversible consequences for brain function [40]. A classic example is the critical period for ocular dominance in the visual system, where monocular deprivation leads to a permanent reduction in cortical responsiveness to the deprived eye if it occurs during this specific window [39]. In contrast, sensitive periods represent broader time windows of gradual plasticity where experience leads to many possible network configurations that can compensate for each other and remain subject to remodeling throughout development and adulthood [40].

The concept of a critical period was first articulated in the 1920s by Charles Stockard, who demonstrated that birth defects in fish embryos resulting from extreme temperatures or toxic chemicals were more likely during periods of rapid cell growth [39]. This concept was later extended to behavioral development through Konrad Lorenz's work on imprinting in ducklings, and ultimately to brain development through the seminal work of David Hubel and Torsten Wiesel on the visual system [39]. Contemporary research has refined our understanding, demonstrating that while these periods represent heightened plasticity, their effects may be more malleable than initially thought, especially through targeted interventions [41].

Understanding the mechanisms governing these plastic epochs is crucial for developing interventions for neurodevelopmental disorders and brain injury. This review synthesizes cross-species evidence on critical period mechanisms and the emerging paradigm of iPlasticity—the induced reinstatement of juvenile-like plasticity in the adult brain [42]. We compare experimental approaches across model organisms and highlight validated neuroplasticity markers with translational potential for therapeutic development.

Molecular and Circuit Mechanisms Governing Critical Period Timing

The opening and closure of critical periods are regulated by a complex interplay of molecular brakes, excitatory-inhibitory balance, and specific signaling pathways. Research across species has identified conserved mechanisms that control these developmental windows, offering potential targets for therapeutic intervention.

Cortical Inhibition and the Parvalbumin Interneuron System

A fundamental mechanism regulating critical period timing involves the maturation of GABAergic inhibition, particularly through parvalbumin-positive (PV+) interneurons [43] [42]. The onset of critical periods coincides with the maturation of these interneurons and the formation of perineuronal nets (PNNs)—specialized extracellular matrix structures that enwrap PV+ interneurons and stabilize synaptic connections [42].

Table 1: Key Molecular Regulators of Critical Period Plasticity

| Molecule/Pathway | Function in Critical Periods | Effect on Plasticity | Experimental Evidence |

|---|---|---|---|

| Parvalbumin (PV+) Interneurons | Establishment of E:I balance; critical period trigger | Delayed maturation extends plasticity; enhanced maturation accelerates closure | Visual cortex OD plasticity; slice electrophysiology [43] [42] |

| Perineuronal Nets (PNNs) | Stabilization of synaptic circuits; structural brake | Enzymatic degradation reopens plasticity in adults | Chondroitinase ABC treatment in visual cortex [42] |

| Lynx1 | Endogenous nicotinic receptor inhibitor | Deletion extends plasticity to adulthood | Visual cortex plasticity in Lynx1 KO mice [43] |

| BDNF/TrkB Signaling | Promotes interneuron maturation; synaptic plasticity | Overexpression accelerates critical period onset | BDNF overexpression studies [44] [42] |

| Oxytocin | GABA polarity switch at birth | Correct timing essential for normal development | Role in ASD models [40] |

| Thalamic Adenosine | Regulates thalamocortical LTD | Increased expression limits TC plasticity in adults | Auditory cortex slice experiments [43] |

The excitation-inhibition (E:I) balance in cortical circuits is crucial for critical period regulation. During development, the maturation of inhibitory circuits initially lags behind excitatory circuitry [39]. The subsequent establishment of appropriate E:I balance marks the onset of the critical period, while its stabilization contributes to closure [43]. In the auditory cortex, for example, E:I balance is established in thalamorecipient layer 4 neurons by postnatal day 12 in rats, coinciding with the critical period for tonal receptive field plasticity [43].

Signaling Pathways and Molecular Brakes

Beyond inhibitory circuitry, several molecular pathways act as "brakes" to limit plasticity after critical period closure. Lynx1, an endogenous inhibitor of nicotinic receptors that exhibits higher expression in adults, constrains plasticity in the visual cortex—its deletion extends plasticity into adulthood [43]. Similarly, the BDNF/tropomyosin kinase receptor B (TrkB) pathway is critical for activity-dependent plasticity processes, including neurogenesis, neuronal differentiation, and synaptic weight regulation [42].

In the auditory system, a thalamic adenosine hypothesis has been proposed, where adenosine accumulation at thalamocortical synapses contributes to the loss of plasticity in adults [43]. These molecular brakes represent potential targets for reopening plasticity in the mature brain.

iPlasticity: Reopening Critical Periods in the Adult Brain

The concept of iPlasticity (induced juvenile-like plasticity) refers to the drug-induced reinstatement of a juvenile-like plastic state in the adult brain [42]. This phenomenon demonstrates that the molecular machinery for heightened plasticity persists in adulthood but is actively suppressed, and can be reactivated through targeted interventions.

Pharmacological Induction of Plasticity

Antidepressants, particularly selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), have shown remarkable ability to reactivate critical period-like plasticity in adult animals. Chronic fluoxetine treatment, when paired with specific training or experience, reopens plasticity in the adult visual cortex, promotes fear extinction, and facilitates the reversal of maladaptive behaviors [42]. This effect is associated with dematuration of PV+ interneurons—a regression to a more immature state characterized by molecular and physiological changes that reduce their inhibitory efficacy [42].

Table 2: Experimental Models of iPlasticity Induction

| Intervention | Experimental Model | Plasticity Outcome | Mechanistic Insights |

|---|---|---|---|

| Chronic Fluoxetine | Adult rat visual cortex; monocular deprivation | Ocular dominance shift; recovery from amblyopia | Reduced intracortical inhibition; increased BDNF; PV+ interneuron dematuration [42] |

| Environmental Enrichment | Rodent models of early adversity | Normalization of HPA axis; reversal of behavioral deficits | Epigenetic modifications; increased synaptic complexity [41] [45] |

| Chondroitinase ABC | Adult mouse visual cortex | Reopening of OD plasticity | PNN degradation; disrupted circuit stabilization [42] |

| Lynx1 Deletion | Adult mouse visual cortex | Extended plasticity to P60 | Disinhibition of nicotinic receptors [43] |

| Psychedelics (e.g., DOI) | Rat claustrum-ACC pathway | Reversal of LTD to LTP | 5-HT2A receptor activation; metaplasticity [46] |

Recently, psychedelic compounds have emerged as powerful inducers of plasticity. These substances, including DOI and psilocybin, activate serotonin 2A receptors (5-HT2AR) and can reopen juvenile-like critical periods for social reward learning in adult mice [46]. In the claustrum-anterior cingulate cortex pathway, the psychedelic DOI reverses the polarity of synaptic plasticity from long-term depression to long-term potentiation [46]. This represents a form of metaplasticity—where the prior history of synaptic activity modifies future plasticity—and may underlie the lasting therapeutic effects of psychedelics in psychiatric disorders.

Cross-Species Validation of Plasticity Markers

Cross-species approaches have been instrumental in validating biomarkers of neuroplasticity. These studies combine genetic and molecular investigations in animals with neuroimaging in humans, providing complementary insights across different scales of resolution [44]. For example, research on fear extinction has demonstrated parallel behaviors in rodents and humans, with impaired extinction in both species associated with the BDNF Met allele and altered fronto-amygdalar circuitry [44]. Similarly, developmental studies show reduced fear extinction during adolescence in both mice and humans, linked to distinct synaptic plasticity patterns in the ventromedial prefrontal cortex [44].

Diagram 1: Mechanisms of iPlasticity Induction. This flowchart illustrates how various interventions target specific molecular and cellular pathways to reactivate juvenile-like plasticity in adult brains, leading to functional recovery and enhanced learning.

Experimental Models and Methodologies for Plasticity Research

Key Experimental Protocols

Visual Cortex Monocular Deprivation Protocol: The ocular dominance shift paradigm represents the gold standard for studying critical period plasticity [42] [39]. In this protocol, one eyelid is surgically closed for a specific duration during the critical period (typically P20-P45 in mice). Visual evoked potentials (VEPs) are then recorded from the binocular region of the primary visual cortex to quantify neuronal responses to stimulation of each eye. The ocular dominance index is calculated as the ratio of contralateral to ipsilateral VEP responses, with shifts indicating experience-dependent plasticity [42]. In iPlasticity studies, this protocol is combined with interventions like chronic fluoxetine administration (typically 3-5 weeks via drinking water) in adult animals to test the reopening of plasticity [42].

Fear Extinction Training: This behavioral paradigm examines plasticity in emotional circuits and has strong cross-species validity [44]. Animals are first trained to associate a neutral conditioned stimulus (CS, e.g., tone) with an aversive unconditioned stimulus (US, e.g., foot shock). After consolidation of this fear memory, extinction training involves repeated presentations of the CS without the US. The reduction in conditioned fear responses (e.g., freezing in rodents, galvanic skin response in humans) measures extinction learning, which depends on prefrontal-amygdala circuitry [44]. This protocol has been used to demonstrate impaired extinction in BDNF Met allele carriers across species [44].

Thalamocortical Slice Electrophysiology: To investigate monosynaptic mechanisms of plasticity, acute brain slices containing the auditory thalamus and cortex are prepared from mice at different developmental stages [43]. Thalamocortical long-term potentiation and depression are induced using pairing protocols that correlate presynaptic thalamic stimulation with postsynaptic cortical depolarization. This approach revealed that thalamocortical synapses lose their plasticity abruptly after postnatal day 15 in mice, coinciding with critical period closure [43].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Research Reagents for Plasticity Studies

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Research Application | Function in Experimental Design |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pharmacological Agents | Fluoxetine, Chondroitinase ABC, DOI | iPlasticity induction; critical period reopening | Target specific molecular pathways (serotonin, extracellular matrix) to remove plasticity brakes [42] [46] |

| Genetic Models | BDNF Met allele mice, Lynx1 KO, PV-Cre lines | Mechanism testing; cross-species validation | Identify causal genes; cell-type specific manipulation; model human genetic variations [43] [44] |

| Viral Vectors | AAV-hSyn-EGFP, DIO-opsins | Circuit mapping; functional manipulation | Label specific projections; optogenetic/chemogenetic control of defined circuits [46] |

| Activity Reporters | c-Fos, Arc, GCaMP | Neural activity mapping | Identify plasticity-related neural ensembles; monitor circuit dynamics in vivo [44] |

| Electrophysiology Systems | Multi-electrode arrays, patch-clamp rigs | Synaptic plasticity quantification | Measure LTP/LTD; characterize E:I balance; single-neuron properties [43] [46] |

Comparative Analysis of Plasticity Across Model Systems

Cross-species approaches provide complementary insights into neuroplasticity mechanisms by leveraging the unique advantages of different model organisms. Rodent models enable precise molecular and cellular manipulation through genetic tools and detailed circuit mapping, while human studies provide essential validation through neuroimaging and behavioral assessment [44]. Non-human primate studies bridge this gap with closer physiological and anatomical similarity to humans.

The BDNF Val66Met polymorphism exemplifies successful cross-species validation. Both humans and mice carrying the Met allele show impaired fear extinction, accompanied by reduced vmPFC activation and elevated amygdala activity [44]. This translational approach confirms the role of BDNF in prefrontal-amygdala circuitry and provides a genetic model for testing novel therapeutics for anxiety disorders.

Similarly, developmental studies reveal conserved patterns of adolescent plasticity across species. Both human and rodent adolescents show reduced fear extinction compared to children and adults, linked to distinct synaptic plasticity patterns in the ventromedial prefrontal cortex [44]. These parallel findings strengthen the translational relevance of developmental plasticity mechanisms.

Diagram 2: Cross-Species Validation Approach. This diagram illustrates how rodent models and human studies provide complementary data that converges to validate neuroplasticity mechanisms and interventions across species.

Implications for Therapeutic Development and Future Directions

The mechanistic understanding of critical periods and iPlasticity opens promising avenues for therapeutic interventions in neurodevelopmental disorders, brain injury, and psychiatric conditions. The recognition that molecular brakes actively suppress plasticity in the adult brain suggests they can be targeted to restore adaptive plasticity when needed.

Combination therapies that pair plasticity-inducing drugs with targeted rehabilitation show particular promise. Clinical studies demonstrate that patients with depression respond better to SSRIs combined with psychotherapy than to either treatment alone [42]. This aligns with the iPlasticity principle: SSRIs may reopen a plastic state, while psychotherapy provides the targeted experience to guide circuit reorganization [42]. Similarly, in animal models, fluoxetine treatment enables recovery from amblyopia in adult rats only when combined with visual training [42].

Future research should focus on several key areas: First, developing cell-type specific interventions that can precisely target plasticity regulators without widespread system effects. Second, establishing biomarkers of plastic states to identify optimal timing for interventions. Third, understanding individual differences in critical period timing and plasticity capacity, potentially informed by genetic variants like BDNF Met. Finally, exploring non-pharmacological approaches to induce iPlasticity, such as exercise or environmental enrichment, which have shown beneficial effects on brain function across species [45].

The continued integration of cross-species approaches will be essential for translating these findings into effective therapies. As we refine our understanding of how to safely harness the brain's plastic potential, we move closer to treatments that can genuinely restore function by remodeling neural circuits, rather than merely managing symptoms.

Measuring Neuroplasticity: From Animal Models to Human Biomarkers

This guide provides an objective comparison of Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation (TMS), Theta-Burst Stimulation (TBS), and Direct Current Stimulation (tDCS) for researchers validating neuroplasticity markers across species. It synthesizes current experimental data, detailed methodologies, and key reagents to inform therapeutic development.

Comparative Performance of Neuromodulation Techniques

The following tables summarize the key electrophysiological effects, therapeutic outcomes, and technical specifications of these neuromodulation techniques, based on recent clinical and pre-clinical findings.

Table 1: Electrophysiological Effects and Neuroplasticity Markers

| Technique | Electrophysiological Readout | Impact on Cortical Excitability | Molecular Markers of Neuroplasticity |

|---|---|---|---|

| TBS (iTBS) | Motor Evoked Potential (MEP) facilitation [47] | Increased excitability (LTP-like) [47] | Increased c-Fos expression (excitatory neurons) [48] |

| TBS (cTBS) | Motor Evoked Potential (MEP) reduction [47] | Decreased excitability (LTD-like) [47] | Increased GAD-65 expression (inhibitory neurons); suppressed c-Fos [48] |

| tDCS (anodal) | Shift in resting membrane potential [48] | Increased excitability [48] | Augmented long-term potentiation (LTP) in animal models [49] |

| tDCS (cathodal) | Shift in resting membrane potential [48] | Decreased excitability [48] | Effects on long-term depression (LTD) [49] |

| rTMS (HF) | MEP amplitude increase [50] | Increased excitability [50] | Modulates beta-band oscillations in PD [51] |

| tBES | MEP changes; LFP voltage dynamics [52] [48] | Polarity- and pattern-dependent plasticity [48] | Induces short-term plasticity in human iEEG [52] |

Table 2: Therapeutic Efficacy and Protocol Parameters

| Technique | Reported Clinical Efficacy | Typical Protocol Parameters | Spatial Resolution |

|---|---|---|---|

| iTBS | Non-inferior to HF-rTMS for depression [47]; Improved working memory response time [49] | 600 pulses; 3-pulse 50 Hz bursts at 5 Hz; 80% AMT [47] [49] | Moderate (focal cortical) |

| cTBS | Induction of inhibitory effects [47] | 300-600 pulses; continuous train [47] | Moderate (focal cortical) |