Unlocking Memory: Neural Mechanisms of Sleep-Dependent Consolidation and Clinical Implications

This article synthesizes current research on the neural mechanisms through which sleep facilitates long-term memory consolidation.

Unlocking Memory: Neural Mechanisms of Sleep-Dependent Consolidation and Clinical Implications

Abstract

This article synthesizes current research on the neural mechanisms through which sleep facilitates long-term memory consolidation. Aimed at researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it explores the foundational roles of specific sleep oscillations—slow waves, spindles, and hippocampal ripples—and their coordination in active systems consolidation. It further reviews cutting-edge methodological approaches for investigating and modulating these processes, examines how disruptions in sleep architecture contribute to memory deficits in clinical populations, and validates key mechanistic theories through meta-analytic and comparative evidence. The conclusion highlights emerging therapeutic strategies and future directions for targeting sleep to enhance cognitive function and treat memory-related disorders.

Core Machinery of Sleep-Mediated Memory: Oscillations, Synaptic Plasticity, and Systems Consolidation

This whitepaper delineates the mechanisms of active systems consolidation, a process whereby memories are gradually stabilized and transformed into long-term storage during sleep through structured dialogue between the hippocampus and neocortex. We synthesize recent neurophysiological and computational evidence demonstrating that sleep oscillations, including slow oscillations, spindles, and sharp-wave ripples, orchestrate the repeated reactivation of hippocampal memory traces and their subsequent integration into neocortical networks. This review provides a detailed framework for researchers and drug development professionals, highlighting specific experimental protocols, key quantitative data, and essential research reagents that underpin this critical neurobiological process.

Memory consolidation is the process that transforms newly encoded, labile memory traces (engrams) into stable long-term memories. The Complementary Learning Systems (CLS) framework posits a division of labor between the hippocampus and neocortex, where the hippocampus enables rapid encoding of episodic information using sparse, pattern-separated codes, while the neocortex employs overlapping, distributed representations adept at extracting semantic structure [1]. Historically, consolidation was viewed as a slow, passive process. The contemporary model of active systems consolidation establishes that sleep provides a unique neurophysiological environment wherein memories are actively and repeatedly reactivated, leading to their gradual redistribution and transformation [2].

This process is not a simple transfer of data. Instead, the hippocampus acts as a teacher, guiding the reorganization of neocortical circuits to incorporate new information without catastrophically interfering with existing knowledge. This "dialogue" is fundamental to building structured knowledge of the world over time and is implicated in the abstraction of gist and the formation of semantic memory [1] [2]. Understanding its mechanisms is paramount for developing therapeutic interventions for memory disorders.

Core Mechanisms of the Hippocampal-Neocortical Dialogue

The dialogue between the hippocampus and neocortex is facilitated by a precise interplay of neurophysiological events and learning mechanisms.

Neuronal Ensemble Reactivation and Replay

A cornerstone of active systems consolidation is the reactivation or replay of hippocampal neuronal firing patterns that occurred during prior wakefulness. This replay occurs predominantly during slow-wave sleep (SWS) and is often initiated by hippocampal sharp-wave ripples (SWRs) [2].

- Temporal Dynamics: Replay events often preserve the temporal order of the original experience. In rodents, the sequential firing of place cells observed during spatial exploration is re-expressed during subsequent SWS on a compressed timescale [2].

- Systems-Level Coordination: Hippocampal replay is not isolated. It occurs in coordination with neuronal firing in prefrontal, parietal, and sensory cortices, as well as subcortical structures like the striatum and amygdala, often with a temporal delay of 40–50 ms, suggesting a hippocampally-initiated spread of activity [2].

- Causal Evidence: Disruption of SWRs during post-learning sleep impairs subsequent memory recall, providing direct causal evidence for their role in consolidation [2].

The Orchestrating Role of Sleep Oscillations

The transition from wake to sleep induces a profound change in brain neurochemistry, characterized by a reduction in acetylcholine levels. This disinhibits hippocampal output and creates a brain state primed for systems consolidation [2]. This state is defined by nested brain oscillations.

NREM Sleep Oscillations and Systems Consolidation

- Slow Oscillations (<1 Hz): Originating in the neocortex, the SO Up-State provides a temporal window of heightened excitability that facilitates the synchronization of other oscillatory events [2].

- Sleep Spindles (12-16 Hz): These thalamocortical oscillations are believed to gate information transfer from the hippocampus to the neocortex. The coincidence of spindles with SO Up-States and hippocampal SWRs is a robust predictor of memory consolidation [1] [2].

- Sharp-Wave Ripples (150-250 Hz): These high-frequency bursts in the hippocampus package the reactivated memory information for broadcast to the neocortex [2].

The hierarchical coupling of these rhythms (SOs → Spindles → SWRs) creates a precise mechanism for timing hippocampal-neocortical communication to optimize synaptic plasticity.

NREM/REM Sleep Alternation and Computational Insights

The distinct stages of sleep play complementary roles. While NREM sleep, with its tightly coupled hippocampal-neocortical dynamics, is ideal for reinstating high-fidelity new memories, REM sleep may facilitate the integration of these memories with existing knowledge structures [1].

Computational models demonstrate how alternating between NREM-like and REM-like states can solve the problem of continual learning in non-stationary environments. In these models:

- NREM: The hippocampus strongly drives the neocortex, helping to "teach" it new, specific attractor states.

- REM: With reduced hippocampal-cortical coupling, the neocortex can more freely explore its existing representational space, effectively rehearsing old memories and protecting them from being overwritten by new information [1].

This alternation enables graceful integration of new information (NREM) with the protection of old knowledge (REM), preventing catastrophic interference [1].

Quantitative Data and Experimental Evidence

Key Neurophysiological Correlates of Consolidation

Table 1: Quantitative Metrics of Sleep-Associated Memory Consolidation

| Metric / Phenomenon | Typical Value / Frequency | Functional Significance | Associated Brain Region |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sharp-Wave Ripple (SWR) | 150-250 Hz [2] | Packages hippocampal memory replay for broadcast. | Hippocampus |

| Sleep Spindle | 12-16 Hz [2] | Facilitates information transfer & cortical plasticity. | Thalamocortical |

| Slow Oscillation (SO) | <1 Hz (0.5-1 Hz) [2] | Synchronizes widespread neural ensembles; provides temporal framework. | Neocortex |

| Reactivation Delay (Hipp→Ctx) | 40-50 ms [2] | Indicates direction of information flow (hippocampus to cortex). | Hippocampus → Neocortex |

| Theta Coherence during Encoding | 4-10 Hz [2] | Predicts strength of subsequent reactivation; associated with salience. | Hippocampus-Prefrontal Cortex |

Behavioral and Systems-Level Outcomes

Table 2: Impact of Sleep on Different Memory Domains

| Memory Type | Effect of Sleep (vs. Wake) | Primary Sleep Stage Involved | Key Supporting Evidence |

|---|---|---|---|

| Declarative (Episodic) | Enhanced recall and reduced forgetting [3] [2] | Slow-Wave Sleep (SWS) | fMRI showing hippocampal-neocortical coupling during SWS predicts recall. |

| Procedural (Motor Skill) | Performance speed and accuracy gains [3] | Both SWS & REM | Sleep-dependent gains without further practice. |

| Emotional Memory | Preservation of affective tone; integration with context [2] | REM (debated) | Selective preservation of emotional objects after sleep. |

| Generalization & Insight | Increased ability to extract gist and rules [1] [2] | NREM/REM alternation | Problem-solving insight increased after sleep. |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

To investigate hippocampal-neocortical dialogue, researchers employ a combination of behavioral, electrophysiological, and pharmacological techniques.

Protocol: Assessing Sleep-Dependent Memory Consolidation in Rodents

Objective: To determine the causal role of specific sleep oscillations in memory consolidation.

Experimental Workflow for Rodent Sleep-Memory Research

Behavioral Training & Encoding:

- Task: Rodents perform a hippocampus-dependent task (e.g., spatial navigation in a Morris water maze or novel object location task).

- Neural Recording: Simultaneously, record electrophysiological signals (EEG, local field potentials (LFP)) from the hippocampus and relevant cortical areas (e.g., prefrontal cortex). Single-unit activity can be recorded to identify place cells.

- Salience Manipulation: To tag memories for preferential consolidation, incorporate novel, aversive, or reward-associated stimuli [2].

Post-Training Sleep Session:

- Allow the animal to sleep for a defined period (e.g., 1-2 hours).

- Continuously record neural activity to identify sleep stages (SWS, REM) and oscillatory events (SWRs, spindles).

Experimental Manipulation (Intervention):

- SWR Disruption: Upon online detection of a hippocampal SWR, deliver a mild auditory stimulus or optogenetic inhibition of hippocampal CA1 neurons to disrupt the replay event without awakening the animal [2].

- Control Group: A yoked control group receives the same stimuli randomly, not time-locked to SWRs.

Memory Retrieval Test:

- After the sleep period, test the animal's memory in the learned task.

- Quantitative Measure: Compare performance (e.g., time to find platform, preference for novel location) between the experimental and control groups. Successful consolidation is inferred from superior performance in the control group.

Protocol: Investigating Systems Consolidation in Humans

Objective: To track the gradual corticalization of memories using neuroimaging.

- Encoding: Participants learn paired-associate words or spatial memories during fMRI scanning.

- Sleep: Participants either sleep or remain awake. Polysomnography (PSG) is used to monitor sleep architecture.

- Retrieval: After sleep (or immediately, or after a delay), participants are tested on the learned material while undergoing fMRI.

- Analysis:

- Activation Shift: Look for a change in the neural correlates of retrieval from being heavily hippocampal-dependent after waking to becoming more neocortex-dependent (e.g., in medial prefrontal cortex) after sleep [2].

- Functional Connectivity: Analyze the strength of hippocampal-cortical functional connectivity during SWS using simultaneous EEG-fMRI. Stronger connectivity during sleep predicts better subsequent recall [1].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagents & Methodologies

Table 3: Essential Reagents and Tools for Investigating Active Systems Consolidation

| Tool / Reagent | Category | Primary Function in Research |

|---|---|---|

| Optogenetics (e.g., ChR2, NpHR) | Neuromodulation | Causally links specific neuronal populations (e.g., CA1 cells firing during SWRs) to memory consolidation by allowing precise inhibition/activation of these cells during sleep [2]. |

| Chemogenetics (DREADDs) | Neuromodulation | Allows longer-term, receptor-mediated manipulation of neural activity in specific circuits (e.g., hippocampal outputs) across full sleep-wake cycles. |

| Polysomnography (PSG) Setup | Electrophysiology | The gold standard for classifying sleep stages in humans and animals via EEG, EOG, and EMG. |

| High-Density EEG / Neuropixels | Electrophysiology | Enables high-resolution recording of brain oscillations (EEG) and single-unit activity (Neuropixels) across multiple brain regions simultaneously. |

| fMRI (with simultaneous EEG) | Neuroimaging | Tracks large-scale brain systems-level changes (corticalization) associated with memory consolidation over time. |

| c-Fos / Arc Immunohistochemistry | Molecular Biology | Tags neurons that were active during a specific behavioral epoch (e.g., encoding), allowing visualization of memory engrams and their reactivation during sleep. |

| Dopamine Receptor Agonists/Antagonists | Pharmacology | Tests the role of dopaminergic signaling (e.g., from VTA), which can tag salient memories for privileged consolidation during sleep [2]. |

The evidence is compelling that the hippocampal-neocortical dialogue during sleep is an active, structured process fundamental to long-term memory formation. The orchestrated interplay of SWRs, spindles, and slow oscillations facilitates the selective reactivation and gradual transformation of memories, enabling their integration into pre-existing cortical networks. For drug development, targeting the neurophysiological substrates of this dialogue—such as enhancing the coupling of sleep oscillations or modulating the tagging of salient memories—presents a promising avenue for treating memory impairments associated with aging, neurodegeneration, and psychiatric disorders. Future research must continue to bridge molecular mechanisms with systems-level dynamics to fully elucidate this foundational process of memory.

Long-term memory formation is a major function of sleep, during which mnemonic representations initially reliant on the hippocampus are transformed into more stable, neocortical stores. This process, known as active systems consolidation, is particularly facilitated by non-rapid eye movement (NREM) sleep [2]. During this offline period, the brain engages in a sophisticated dialog between the hippocampus and neocortex, preventing interference from conscious information processing and enabling the stabilization of memories [4]. The mechanistic underpinning of this hippocampo-neocortical dialog relies on the precise, hierarchical coordination of three cardinal neuronal oscillations that characterize NREM sleep: slow oscillations (SOs), sleep spindles, and hippocampal ripples [4] [5]. Under the global control of SOs, sleep spindles cluster hippocampal ripples, creating precisely timed temporal windows for the transfer of local information from the hippocampus to distributed neocortical sites [4]. This tripartite mechanism provides the temporal scaffold necessary for neuronal information transfer in the absence of external stimuli.

Research employing intracranial electroencephalogram (iEEG) recordings in humans has confirmed that these three oscillations are functionally coupled in the hippocampus itself, offering a mechanistic account for information transfer during sleep [4]. The depolarizing SO up-states facilitate the emergence of spindles, which in turn bundle local information units (ripples) to shuttle them to the neocortex for long-term storage. This review synthesizes evidence from neurophysiological and behavioral studies to explore the mechanisms of this hierarchical nesting, its role in memory consolidation, experimental methodologies for its investigation, and emerging therapeutic interventions that target these oscillations to enhance memory function.

The Hierarchical Nesting Model

The hierarchical nesting model posits that slow oscillations, spindles, and ripples do not occur in isolation but are systematically coupled in a temporally precise structure. This coupling creates optimal conditions for memory consolidation by coordinating the timing of hippocampal memory trace reactivation with periods of heightened cortical receptivity [4] [5].

Slow Oscillations: The Master Regulator

Slow oscillations (SOs), occurring at approximately 0.5-1 Hz, reflect global fluctuations in neuronal excitability resulting from alternating phases of joint hyperpolarization (down-states) and depolarization (up-states) in large neuron populations [4]. These high-amplitude waves emerge spontaneously in neocortical regions, particularly prefrontal areas, and travel as waves across the entire neocortex, hippocampus, and thalamus [4]. The SO up-states create a permissive environment for neuronal activity by depolarizing membrane potentials and increasing cortical excitability, thereby facilitating the emergence of thalamocortical sleep spindles and enabling synaptic plasticity necessary for long-term memory formation [5]. The down-states, in contrast, represent periods of generalized neuronal silence and hyperpolarization, which are thought to contribute to synaptic downscaling—a process that helps maintain synaptic homeostasis while preserving memory traces [2].

Sleep Spindles: The Temporal Coordinator

Sleep spindles are brief bursts of oscillatory activity between 11-16 Hz that are generated through interactions between reticular thalamic neurons and thalamocortical cells [4]. These waxing-and-waning waveforms typically last less than 500 milliseconds and are triggered by corticothalamic input during SO up-states [5]. While spindles occur throughout NREM sleep, those coupled with SOs during slow-wave sleep (SWS) are proposed to be particularly critical for memory consolidation, as opposed to spindles in N2 sleep which may primarily serve to raise arousal thresholds and protect sleep continuity [5]. Spindles are not uniform in their characteristics; fast spindles (12-16 Hz) are modulated by SO up-states in the hippocampus, whereas slow spindles (8-12 Hz) show different modulation patterns and may serve distinct functions [4]. Through their rhythmic structure, spindles create precise temporal windows that cluster and organize hippocampal ripples for targeted information transfer to cortical networks.

Hippocampal Ripples: The Information Carriers

Hippocampal ripples are high-frequency oscillations (~80-100 Hz in humans, ~200 Hz in rodents) that originate in the CA1 subregion and accompany the reactivation of local memory traces [4] [2]. These brief, high-frequency bursts coincide with the repeated replay of firing patterns in hippocampal neuron ensembles that were active during prior learning experiences [2]. Ripples occur during sharp-wave events, which are thought to represent synchronous population activity in CA3 that drives reactivation in CA1. The hierarchical model demonstrates that spindles cluster these ripples in their troughs, providing fine-tuned temporal frames for the hypothesized transfer of hippocampal memory traces to the neocortex [4]. This nested organization ensures that hippocampal information is released at optimal moments for cortical integration, facilitating the gradual transformation of labile hippocampal-dependent memories into stable cortical representations.

Table 1: Characteristics of the Three Cardinal Oscillations in Human NREM Sleep

| Oscillation Type | Frequency Range | Origin | Primary Function |

|---|---|---|---|

| Slow Oscillations (SOs) | ~0.5-1 Hz | Prefrontal Neocortex | Global coordinator of excitability; groups spindles and ripples |

| Sleep Spindles | 12-16 Hz (fast) | Thalamocortical Networks | Temporal coordinator; clusters hippocampal ripples |

| Hippocampal Ripples | 80-100 Hz (human) | Hippocampal CA1 | Information carriers; accompany memory trace reactivation |

Experimental Evidence and Methodologies

Key Findings from Human Intracranial Recordings

Direct evidence for the hierarchical nesting of SOs, spindles, and ripples comes from intracranial electroencephalogram (iEEG) recordings in epilepsy patients, which provide unparalleled spatial and temporal resolution for measuring these electrophysiological events [4]. In a seminal 2015 study, researchers analyzed iEEG from hippocampal depth electrodes implanted bilaterally in 12 patients with pharmaco-resistant epilepsy, recording during natural sleep for an average of 10.65 hours per night [4]. Using cross-frequency phase-amplitude coupling analyses, the study demonstrated that spindles were significantly modulated by the up-state of SOs, with spindle power showing a 45.6% increase during SO up-states compared to pre-SO intervals [4]. Furthermore, spindles were found to cluster ripples in their troughs, providing the temporal structure for coordinated information transfer.

Employing event-locked analysis and comodulogram approaches, the researchers detected an average of 545 SOs, 821 spindles, and 166 ripples per participant in the hippocampus during NREM sleep [4]. The preferred phases of SO-spindle modulation clustered significantly around the SO up-state across participants, confirming the systematic temporal relationship between these oscillations. Notably, this coupling was specific to fast spindles (12-16 Hz) in the hippocampus, whereas SOs recorded at scalp electrodes grouped both fast and slow spindles, suggesting regional specialization in cross-frequency coupling [4].

Neuronal Ensemble Reactivation and Replay

Complementing the oscillation coupling findings, studies in rodents and humans have demonstrated that hippocampal neuronal ensembles active during waking experiences are spontaneously reactivated during subsequent sleep, particularly during sharp-wave ripple events [2]. This replay preserves the temporal order of firing observed during encoding and is thought to drive the gradual transformation and integration of memory representations in neocortical networks [2]. In humans, functional MRI and EEG studies provide indirect evidence for such memory replay during sleep, while intracranial recordings in epilepsy patients have shown that stimulus-specific gamma-band patterns during picture encoding are reactivated by ripples during subsequent sleep, with the timing of replay predicting later recall versus forgetting of items [2].

The coordination between hippocampal replay and sleep oscillations extends beyond the hippocampus proper. Simultaneous recordings from multiple brain regions reveal that hippocampal reactivations occur in coordination with neuronal firing in the neocortex, striatum, amygdala, and ventral tegmental area, often with a temporal delay of 40-50 milliseconds between hippocampus and other areas [2]. This temporal pattern suggests that ripple-associated memory reactivations originating in the hippocampus spread to extra-hippocampal networks, gradually strengthening cortical memory traces through repeated co-activation.

Table 2: Quantitative Parameters from Human Hippocampal Recordings During NREM Sleep

| Parameter | Average Value | Measurement Details |

|---|---|---|

| SO Density | 3.7 events/minute | Detected in hippocampal iEEG |

| Spindle Density | 5.4 events/minute | Fast spindles (12-16 Hz) in hippocampus |

| Ripple Density | 1.2 events/minute | ~80-100 Hz oscillations in hippocampus |

| SO-Spindle PAC | Preferred phase: 160° | Phase-amplitude coupling in hippocampal SO up-state |

| Spindle Power Increase | 45.6% (SD=40.5) | During SO up-state vs. pre-SO baseline |

| Maximum Power Frequency | 14.5 Hz (SD=2.8) | Within spindle range during SO up-state |

Experimental Protocols and Detection Algorithms

The investigation of SO-spindle-ripple coupling employs sophisticated detection algorithms and analytical approaches. For identifying discrete oscillatory events in electrophysiological recordings, researchers typically implement established detection algorithms with specific parameters [4]:

SO Detection: SOs are identified based on their characteristic frequency (~0.75 Hz) and amplitude criteria, with down-states (troughs) and up-states (peaks) defined relative to the oscillation phase. In scalp EEG, SO up-states correspond to negative peaks, while in iEEG depth recordings, this relationship is inverted [4].

Spindle Detection: Spindles are detected as brief oscillations in the 12-16 Hz range with characteristic waxing-and-waning amplitude morphology. Algorithms typically apply bandpass filtering followed by amplitude thresholding and duration criteria (e.g., 0.5-3 seconds) [4].

Ripple Detection: Hippocampal ripples are identified as high-frequency bursts (~80-100 Hz in humans) that exceed a certain amplitude threshold relative to background activity. Detection often involves filtering in the ripple frequency band and applying root-mean-square smoothing before event extraction [4].

For analyzing cross-frequency coupling, phase-amplitude coupling (PAC) analysis is employed to quantify whether the amplitude of a faster oscillation (e.g., spindles) is systematically modulated by the phase of a slower oscillation (e.g., SOs) [4]. This can be visualized using time-frequency representations (TFRs) time-locked to events of interest, or through comodulograms that simultaneously assess PAC across a wider range of frequency pairs [4]. The robustness of these analytical approaches has been demonstrated through their sensitivity to a wide range of detection thresholds, with results remaining consistent across different parameter settings [4].

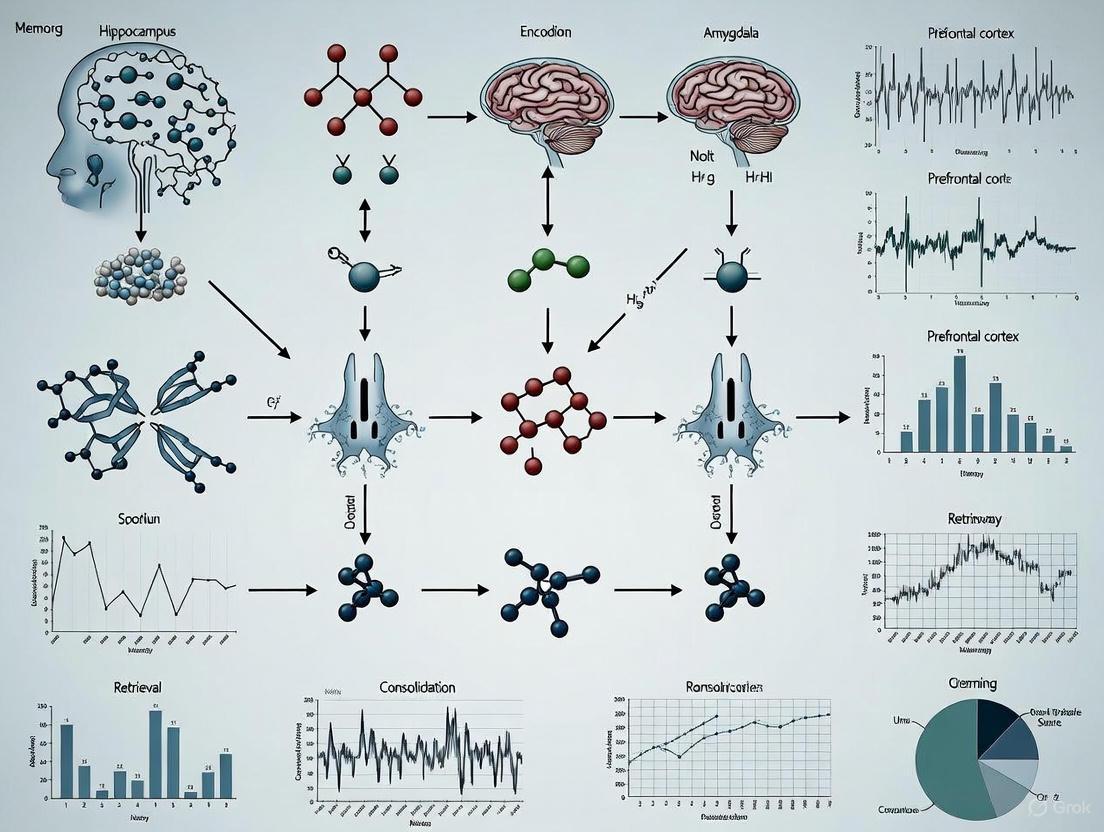

Diagram 1: Hierarchical Nesting of Sleep Oscillations in Memory Consolidation. This diagram illustrates the temporal and functional relationships between slow oscillations, sleep spindles, and hippocampal ripples during NREM sleep. SO up-states trigger spindles, which in turn cluster ripples in their troughs, creating precise timing windows for memory trace reactivation and systems consolidation.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagents and Methodologies

Investigating the triad of SOs, spindles, and ripples requires specialized methodological approaches and analytical tools. The following table summarizes key resources and techniques employed in this research domain.

Table 3: Essential Methodologies for Investigating Sleep Oscillation Coupling

| Methodology/Resource | Function/Application | Key Specifications |

|---|---|---|

| Intracranial EEG (iEEG) | Direct recording of hippocampal oscillations in humans | Depth electrodes implanted bilaterally in hippocampus; typically 10+ hours recording during natural sleep [4] |

| Scalp EEG | Non-invasive measurement of sleep architecture and oscillations | High-temporal resolution recording; electrodes placed according to 10-20 system; includes central (Cz) derivation [4] |

| Phase-Amplitude Coupling (PAC) Analysis | Quantifies modulation of faster oscillation amplitude by slower oscillation phase | Cross-frequency coupling analysis; event-locked time-frequency representations and comodulograms [4] |

| Oscillation Detection Algorithms | Automated identification of SOs, spindles, and ripples in continuous recordings | Established detection criteria with adjustable thresholds; robust across parameter variations [4] |

| Transcranial Direct Current Stimulation (tDCS) | Non-invasive neuromodulation to enhance slow-wave activity | Anodal stimulation of frontocortical regions during SWS; increases slow-wave activity and memory retention [5] |

| Closed-Loop Auditory Stimulation | Timed sensory stimulation to enhance oscillation coupling | Precisely timed auditory cues during SO up-states to augment spindle activity and memory consolidation [5] |

Implications for Therapeutic Interventions and Future Research

The mechanistic understanding of SO-spindle-ripple coupling has inspired novel therapeutic approaches aimed at enhancing memory consolidation, particularly in populations with disrupted sleep architecture. Emerging neuromodulation techniques, such as transcranial direct current stimulation (tDCS) and closed-loop auditory stimulation, leverage EEG-based insights to enhance SWS and improve memory outcomes [5]. These interventions typically target slow oscillations to augment their amplitude and regularity, thereby strengthening the temporal framework for spindle generation and ripple coupling.

Studies employing anodal tDCS over frontocortical regions during SWS have demonstrated increased slow-wave activity and improved retention of declarative memories [5]. Similarly, closed-loop auditory stimulation systems deliver precisely timed auditory cues during SO up-states, which has been shown to augment subsequent spindle activity and strengthen memory consolidation [5]. These approaches represent promising non-pharmacological interventions for counteracting age-related memory decline and mitigating memory deficits associated with neurological disorders that disrupt SWS microstructure, such as epilepsy and depression [5].

Future research directions include refining these stimulation approaches to achieve more precise targeting of oscillation coupling, evaluating their long-term efficacy across diverse populations, and exploring combination therapies that simultaneously enhance multiple components of the SO-spindle-ripple triad. Additionally, further investigation is needed to understand how disruptions to SWS—due to lifestyle factors, ageing, neurological disorders, or pharmacological agents—differentially impact oscillation coupling and memory consolidation [5]. Such research holds promise for developing targeted interventions to optimize sleep-dependent memory processes and preserve cognitive function across the lifespan.

The Synaptic Homeostasis Hypothesis (SHY) proposes a fundamental function of sleep: to renormalize synaptic strength that has accumulated throughout the brain as a result of plasticity during wakefulness [6] [7]. During wake, the brain adapts to an ever-changing environment, and this learning is largely mediated by synaptic potentiation within relevant neural circuits. This strengthening occurs through various mechanisms, including long-term potentiation (LTP), which enhances synaptic transmission and increases the consumption of cellular energy and supplies [7] [8]. However, a net increase in synaptic strength creates several challenges: it saturates the ability to learn, reduces the selectivity of neuronal responses by degrading the signal-to-noise ratio (S/N), and increases cellular stress [7] [9]. SHY posits that sleep is the price the brain pays for this waking plasticity; it is the period when the brain, disconnected from the environment, can systematically downscale synaptic strength to restore homeostasis, thereby recovering learning capacity and improving S/N while preserving the most robust memory traces [7] [8].

Core Principles and Neurobiological Constraints of SHY

The hypothesis is built upon key neurobiological and informational constraints faced by neurons. Energetically, neuronal firing is expensive, and informationally, a neuron acts as a bottleneck, integrating thousands of inputs to produce a binary output—to fire or not to fire [7]. This forces neurons to fire sparsely and selectively, responding primarily to "suspicious coincidences" of input that signal meaningful environmental regularities [7]. To communicate these detections effectively, synapses carrying these signals must be strong. Consequently, SHY outlines several heuristic rules for neuronal plasticity [7]:

- Learning by Potentiation in Wake: Synaptic potentiation should be the primary mechanism for new learning during wakefulness, allowing signals about salient events to percolate through the brain.

- Wake-Linked Plasticity: This potentiation should occur during wakefulness when learning is guided by environmental feedback, preventing the maladaptive strengthening of fantasies during sleep.

- Renormalization in Sleep: Synaptic renormalization, through net depression, should occur during sleep. In this off-line state, spontaneous brain activity allows for a comprehensive sampling of the brain's overall statistical knowledge, avoiding the biased sampling of the immediate "here and now" that characterizes wakefulness [7]. This process solves the plasticity-stability dilemma by preventing the forgetting of older memories in favor of recent experiences [7].

Molecular Mechanisms of Synaptic Downscaling

Synaptic downscaling is a form of homeostatic plasticity that reduces synaptic strength in a multiplicative manner, proportionally weakening synapses to preserve their relative weights and the information they encode [10]. This section details the key molecular players and pathways involved.

Key Immediate Early Genes and Proteins

The following table summarizes the critical immediate early genes and their functions in synaptic downscaling.

Table 1: Key Immediate Early Genes in Synaptic Downscaling

| Molecule | Primary Function | Role in Downscaling |

|---|---|---|

| Polo-like kinase 2 (Plk2/SNK) | Activity-induced serine/threonine kinase [10] | Is both necessary and sufficient for downscaling; phosphorylates synaptic proteins to promote spine shrinkage and AMPA receptor endocytosis [10]. |

| Homer1a | Activity-regulated scaffolding protein [10] | Disrupts postsynaptic density architecture, facilitating internalization of AMPA receptors and contributing to synaptic depression [10]. |

| Arc (Activity-regulated cytoskeleton-associated protein) | Interacts with endocytic machinery [10] | Promotes the internalization of AMPA-type glutamate receptors, a primary mechanism for reducing synaptic strength [10]. |

| Narp (Neuronal activity-regulated pentraxin) | Secreted protein that aggregates AMPA receptors [10] | Contributes to the homeostatic adjustment of synaptic AMPA receptor content in response to network activity [10]. |

Visualization of the Downscaling Pathway

The diagram below illustrates the core molecular pathway triggered by sustained neuronal activity to mediate synaptic downscaling.

Additional Molecular Mechanisms

Beyond IEGs, other critical processes contribute to downscaling. Protein degradation via the ubiquitin-proteasome system is employed to remove key synaptic proteins. For instance, Plk2 phosphorylates the spine-associated Rap GTPase activating protein (SPAR), leading to its ubiquitination and degradation, which facilitates spine shrinkage [10]. Furthermore, transcriptional repression pathways are activated to suppress the synthesis of synaptic proteins, thereby shifting the balance towards a less potentiated synaptic state [10].

Experimental Evidence and Methodologies

Evidence for SHY comes from biochemical, electrophysiological, and anatomical studies demonstrating that synaptic strength is higher after wake and lower after sleep.

Key Experimental Findings

Table 2: Summary of Key Experimental Evidence for SHY

| Experimental Approach | Key Finding | Citation |

|---|---|---|

| Ultrastructural Imaging (EM) | The axon-spine interface (synaptic size) decreased by ~18% after 6-8 hours of sleep compared to wake in mouse cortex [8]. | [8] |

| Electrophysiology (in vivo fEPSP) | Field excitatory postsynaptic potentials (fEPSPs) in rodent cortex and hippocampus increase with wake duration and decrease during sleep [8]. | [8] |

| Biochemistry (Synaptoneurosomes) | Cortical and hippocampal synaptoneurosomes show ~20-40% higher levels of GluA1 and phosphorylated CaMKII after sleep deprivation vs. sleep [9]. | [9] |

| In vivo Plasticity (Optogenetics) | During SWS-like cortical Up states, presynaptic stimulation alone induces synaptic depression; only inputs contributing to postsynaptic spiking are protected [11]. | [11] |

| Two-photon Spine Imaging | Dendritic spine/filopodia density in mouse somatosensory cortex decreased by ~5% after 2 hours of sleep and increased by ~5% after 2 hours of sleep deprivation [9]. | [9] |

Detailed Experimental Protocol: In Vivo Synaptic Plasticity During Network Oscillations

A pivotal study directly investigated how cortical network states gate synaptic plasticity rules in vivo [11]. The following workflow details the methodology.

Workflow Explanation: This protocol utilizes urethane-anesthetized mice exhibiting spontaneous Slow-Wave-Sleep (SWS)-like dynamics (Up-Down states) [11]. Researchers perform whole-cell recordings from layer 2/3 pyramidal neurons in the barrel cortex while using a closed-loop system to optogenetically stimulate presynaptic layer 4 afferents specifically during either Up or Down states [11]. Different pairing protocols are applied to test plasticity rules:

- During Down states: Pairing presynaptic stimulation with a postsynaptic spike within a 10ms window induces conventional STDP (t-LTP or t-LTD) [11].

- During Up states: Presynaptic stimulation alone, without a postsynaptic spike, leads to synaptic depression. Inputs that successfully contribute to postsynaptic spiking are protected from this weakening [11]. The key outcome is that slow-wave oscillations gate plasticity rules, creating a bias toward synaptic depression during Up states that provides an input-specific downscaling mechanism, improving the signal-to-noise ratio in cortical circuits [11].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents

Table 3: Essential Reagents for Studying Synaptic Downscaling

| Reagent / Tool | Function in Research |

|---|---|

| GABAA Receptor Antagonists (e.g., Bicuculline, Picrotoxin) | Chemically induce chronic network hyperactivity in neuronal cultures to trigger homeostatic synaptic downscaling [10]. |

| Channelrhodopsin-2 (ChR2) | Used for optogenetic stimulation of specific presynaptic pathways (e.g., L4 to L2/3) with high temporal precision during in vivo electrophysiology [11]. |

| Phosphospecific Antibodies (e.g., pCaMKIIα) | Serve as molecular readouts for plasticity-related signaling activity in tissue samples across sleep-wake states [12]. |

| RNA Interference (RNAi) | Knocks down expression of specific genes (e.g., Plk2) in neurons to test their necessity for the downscaling process [10]. |

| Serial Block-Face Scanning Electron Microscopy (SBEM) | Provides high-resolution ultrastructural data to quantify changes in synaptic size and morphology between sleep and wake conditions [8]. |

Integration with Memory Consolidation and Current Debates

SHY is a key component in the broader thesis of memory consolidation during sleep. It is integrated into the active systems consolidation theory, which posits that memories are reactivated and redistributed from the hippocampus to the neocortex during sleep [13]. Within this framework, global synaptic downscaling is thought to work in tandem with local synaptic potentiation. The downscaling globally reduces the strength of synapses, which diminishes background noise and saves energy, while simultaneously protecting and thereby effectively strengthening the recently activated, memory-relevant circuits that undergo reactivation and local potentiation [13]. This synergy is thought to enhance the signal-to-noise ratio of memories, leading to their consolidation.

However, the field actively debates the exclusivity of net synaptic weakening during sleep. Some studies report sleep-dependent synaptic strengthening in specific circuits following learning [9]. Furthermore, research suggests that sleep can promote both synaptic homeostasis and restructuring, with mechanisms like long-term potentiation (LTP) potentially occurring near transitions between slow-wave sleep (SWS) and REM sleep, leading to a reorganization of synaptic weight patterns rather than simple, uniform downscaling [12]. This indicates that the competing theories of synaptic homeostasis and synaptic embossing are not mutually exclusive but may represent complementary stages of a complex memory consolidation process [12].

The formation of long-term memories relies on a sophisticated molecular dialogue between synapses and the nucleus, a process critically orchestrated during sleep. This whitepaper delineates the foundational mechanisms whereby immediate-early genes (IEGs) act as genomic gatekeepers, synaptic tagging and capture (STC) provides a synapse-specific addressing system, and protein synthesis delivers the functional effector molecules for memory consolidation. Within the context of sleep-dependent memory processing, we synthesize current experimental evidence, present quantitative data on gene expression and plasticity, detail key methodological protocols, and visualize core signaling pathways. This resource is designed to equip researchers and drug development professionals with the mechanistic insights and practical tools necessary to advance the study of memory and its disorders.

Memory consolidation involves the conversion of labile short-term memories into stable long-term forms, a process that is markedly enhanced during sleep [14]. At the cellular level, this requires de novo gene transcription and protein synthesis to stabilize synaptic changes. The molecular triad of IEGs, protein synthesis, and synaptic tagging forms a functional unit that solves a fundamental challenge: how to achieve synapse-specific plasticity within a neuron possessing thousands of synapses, each with a unique history of activity.

The Synaptic Tagging and Capture (STC) hypothesis provides an elegant solution by dissociating the initial, local events at a synapse from the subsequent, cell-wide availability of plasticity-related products (PRPs) [15]. According to this model, a stimulating event sets a local "tag" at activated synapses while simultaneously triggering the synthesis of PRPs, which can then be captured by tagged synapses to stabilize the change in synaptic strength. Immediate-early genes function as critical initiators of this process, serving as rapid-response genes that are transcribed without the need for de novo protein synthesis, many of which encode transcription factors or direct effector proteins that regulate synaptic plasticity [16] [17]. The specific molecular architecture of IEGs facilitates their rapid induction, enabling them to act as a gateway to the genomic response required for long-term memory.

Core Molecular Mechanisms

Immediate-Early Genes: Gateways to the Genomic Response

Immediate-early genes are defined by their rapid and transient upregulation in response to neural activity, independent of new protein synthesis. They represent a standing response mechanism that is activated at the transcription level as a first round of response to stimuli [16].

Functional Classification of IEGs

IEGs can be broadly classified into two functional categories based on their protein products and downstream effects, as detailed in Table 1.

Table 1: Functional Classification of Key Neuronal Immediate-Early Genes

| Gene Symbol | Name | Protein Function | Role in Plasticity |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fos, Jun | FBJ osteosarcoma oncogene, Jun proto-oncogene | Transcription factors (AP-1 complex) | Regulate expression of downstream late-response genes [16] |

| Egr1/Zif268 | Early growth response 1 | Zinc-finger transcription factor | Critical for synaptic plasticity and memory consolidation [16] [18] |

| Arc/Arg3.1 | Activity-regulated cytoskeleton-associated protein | Direct effector protein, regulates AMPA receptor endocytosis | Mediates homeostatic scaling and synaptic depotentiation [15] [16] |

| Homer1a | Homer protein homolog 1A | Scaffolding protein at postsynaptic density | Modulates metabotropic glutamate receptor signaling [16] |

Genomic and Regulatory Features Enabling Rapid Response

The exceptional induction kinetics of IEGs—often reaching peak expression within 30 minutes of stimulation—are facilitated by distinct genomic architectural features [17]. Compared to delayed primary response genes and secondary response genes, IEGs possess:

- Short primary transcripts with fewer exons, enabling rapid transcription and processing.

- High-affinity TATA boxes in their core promoters, facilitating efficient transcription initiation.

- Over-representation of transcription factor binding sites (e.g., for CREB, SRF) in upstream regulatory sequences.

- Constitutively accessible promoter chromatin states, maintained through histone acetylation, which preclude the need for slow chromatin remodeling events [16] [17].

The rapid shut-off of IEG expression is equally critical and is achieved through mRNA destabilizing elements in the 3' untranslated regions (UTRs) and rapid proteolysis of the translated proteins [16].

Synaptic Tagging and Capture: A Synapse-Specific Addressing System

The Synaptic Tagging and Capture hypothesis explains how the persistence of synaptic potentiation is determined not solely at the moment of encoding but can be influenced by neural activity both before and after the event [15].

The Revised STC Hypothesis

The original hypothesis has been revised based on key findings that the induction of a synapse-specific 'tagged' state and the expression of long-term potentiation (LTP) are dissociable. Furthermore, the synthesis of plasticity-related products (PRPs) occurs not only in the soma but also in dendrites, allowing for compartmentalized protein availability [15]. The core steps of the revised STC model are:

- Induction and Tag Setting: The induction of synaptic plasticity (e.g., by a weak tetanus) sets a local, protein synthesis-independent 'tag' at the activated synapse. This tag serves as a hypothetical molecular marker.

- PRP Synthesis and Availability: Strong stimulation (e.g., a strong tetanus) or other neuromodulatory events elsewhere on the neuron triggers the synthesis of PRPs. These can be proteins or mRNAs synthesized in the soma or locally in dendrites.

- Capture and Stabilization: Diffusible PRPs are captured specifically by synapses that possess a tag. This interaction stabilizes the initial plastic change, converting early-LTP into protein synthesis-dependent late-LTP (L-LTP).

- Cross-Capture: Evidence suggests that a common pool of PRPs can be captured to stabilize both LTP and long-term depression (LTD), indicating that the tag, not the identity of the PRP, may determine the direction of plasticity [15] [19].

This model accounts for behavioral phenomena like "behavioral tagging," where a weak memory event, which alone would be transient, can be consolidated into a long-term memory if it is associated with a novel or arousing experience that provides the necessary PRPs [15].

Local Protein Synthesis: Compartmentalized Control of the Synaptic Proteome

The local translation of mRNA in dendrites provides a critical mechanism for achieving input-specificity in synaptic plasticity, solving the problem of targeting gene products to a small fraction of the thousands of synapses a neuron possesses.

- mRNA Trafficking: A subset of neuronal mRNAs, including those encoding key IEGs like Arc and Homer1a, are transported to dendritic compartments in a translationally repressed state. This transport is mediated by cis-acting elements in their 3'UTRs (e.g., dendritic targeting elements) and trans-acting RNA-binding proteins like ZBP1 [19].

- Local Translation Activation: Synaptic activity triggers the release of translational repression and the local synthesis of proteins. This allows for rapid, synapse-autonomous modification of the synaptic proteome without involving the somatic nucleus.

- Protein Homeostasis: Local protein degradation via the ubiquitin-proteasome system works in concert with local synthesis to maintain synaptic protein homeostasis, facilitating the removal of existing proteins to make way for newly synthesized ones during plasticity [19].

Signaling Pathways and Molecular Interactions

The molecular events of memory consolidation are governed by specific signaling cascades that connect synaptic activity to nuclear gene expression and local protein synthesis. The following diagram illustrates the core signaling pathway from synaptic activation to the synthesis of Plasticity-Related Proteins (PRPs).

Figure 1: Core Signaling Pathway from Synaptic Activation to PRP Synthesis and Capture. Synaptic activity triggers calcium influx through NMDA receptors and voltage-gated channels, leading to the parallel activation of local synaptic tagging mechanisms (via CaMKII) and nuclear gene transcription (via the CaMKIV/CaMKK pathway and CREB phosphorylation). IEGs are rapidly transcribed, leading to the synthesis of PRP mRNAs, which are transported to dendrites for local translation. PRPs are then captured by tagged synapses to stabilize LTP.

Distinct Kinase Roles in STC

Pharmacological studies using extended in vitro LTP protocols have dissected the distinct contributions of calcium/calmodulin-dependent protein kinases (CaMKs):

- CaMKII in Tag Setting: Transient inhibition of CaMKII with KN-93 during weak tetanization blocks the setting of the synaptic tag, preventing the subsequent stabilization of early-LTP into late-LTP, without affecting the synthesis of PRPs [20].

- CaMKIV in PRP Synthesis: Inhibition of the CaMKK-CaMKIV pathway with STO-609 does not prevent tag setting but blocks the synthesis and/or availability of PRPs, thereby impairing the conversion of early-LTP to late-LTP in a separate, strongly tetanized pathway [20].

This demonstrates a clear functional dissociation: CaMKII is critical for the local, synapse-specific process of tag setting, while the CaMKK-CaMKIV axis is essential for the cell-wide regulation of PRP synthesis, likely through the phosphorylation of transcription factors like CREB.

Quantitative Data and Experimental Evidence

Gene Expression Kinetics and Classification

Global expression profiling following growth factor stimulation in human glioblastoma cells has provided a quantitative framework for classifying induced genes, as summarized in Table 2. This classification is directly analogous to the gene expression program initiated by neuronal activity during learning.

Table 2: Quantitative Classification of Activity-Induced Genes Based on Expression Kinetics and Protein Synthesis Dependence

| Gene Class | % of Induced Genes | Peak Induction Time | Protein Synthesis Dependence | Key Functional Roles |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Immediate-Early Genes (IEGs) | 37% (49/133) | ~30 minutes | Independent | Transcriptional regulators (e.g., Fos, Egr1); gateway to genomic response [17] |

| Delayed Primary Response Genes | 44% (58/133) | 2-4 hours | Independent | Effector proteins (e.g., structural proteins, signaling molecules) [17] |

| Secondary Response Genes | 19% (26/133) | 2-4 hours | Dependent | Downstream effectors whose induction relies on IEG protein products [17] |

Sleep-Dependent Memory and Affective Processing

Human studies utilizing sleep and sleep deprivation paradigms provide direct behavioral and physiological evidence for the role of sleep in memory consolidation, aligning with the molecular mechanisms of STC and IEG function.

- Short-term Preservation: Sleep, compared to sleep deprivation, equally preserves both negative and neutral memories over a 12-hour period, maintaining their affective tones [14].

- Long-term Affective Depotentiation: At a 60-hour delayed test, sleep leads to a significant reduction in the emotional response to negative memories, effectively depotentiating their affective tone while sleep deprivation does not [14].

- Neural Correlates: Event-related potential (ERP) data show that sleep-deprived individuals process remote emotional memories with a different neurocognitive signature, including an enhanced Late Positive Component (LPC), suggesting less efficient or altered reconciliation of memory and emotion traces [14].

This temporal dynamic—preservation followed by selective affective depotentiation—suggests that sleep actively participates in both stabilizing memory content and regulating its emotional valence, processes that likely involve IEG-driven restructuring of synaptic networks.

Essential Methodologies and Protocols

This section details key experimental protocols used to investigate IEG function and synaptic tagging, providing a toolkit for researchers in the field.

In Vitro Synaptic Tagging and Capture Protocol

This electrophysiological protocol in hippocampal brain slices is the gold standard for studying STC and allows for the pharmacological dissection of underlying mechanisms [20].

- Preparation: Hippocampal slices (400 μm) from rodents are maintained in an interface chamber at 32°C with continuous perfusion of artificial cerebrospinal fluid (aCSF). Test stimulation is delivered at a very low frequency (e.g., 0.0067 Hz) to minimize baseline molecular activity.

- Pathway Independence: Three independent stimulating electrodes are positioned in the stratum radiatum of CA1 to activate separate synaptic inputs converging on the same population of postsynaptic neurons. Independence is verified by the absence of paired-pulse facilitation between pathways.

- Stimulation Protocols:

- Strong Tetanization: Three trains of 100 pulses at 100 Hz, delivered at 10-minute intervals. This protocol reliably induces late-LTP (L-LTP), which requires protein synthesis and lasts >10 hours.

- Weak Tetanization: A single theta-burst stimulation (e.g., four trains of five pulses at 100 Hz). This protocol induces early-LTP (E-LTP), which is protein synthesis-independent and decays to baseline within 2-3 hours.

- Tag-Capture Interaction: To demonstrate STC, a weak tetanus is applied to one pathway (sets a tag) either shortly before or after a strong tetanus to a separate pathway (provides PRPs). The persistence of E-LTP on the weak pathway is monitored. Conversion of E-LTP to L-LTP on the weak pathway indicates successful "capture" of PRPs.

- Pharmacological Dissection: Kinase inhibitors (e.g., KN-93 for CaMKII, STO-609 for CaMKK) can be applied during specific time windows to dissect their roles in tag setting versus PRP synthesis. Rapid drug washout is critical for these reversible inhibition experiments.

Assessing IEG Function with Antisense Oligonucleotides

Localized disruption of specific IEGs in vivo allows researchers to establish a causal link between their expression and long-term memory consolidation [18].

- Design: Antisense oligonucleotides (ODNs), typically 15-25 bases long, are designed to be complementary to the translation start site of the target IEG mRNA (e.g., Arc, c-fos). Mismatch or scrambled ODNs serve as controls.

- Administration: ODNs are dissolved in artificial CSF and administered via intracerebral injection (e.g., into the hippocampus or amygdala) in a volume of 0.5-1.0 μl. A common protocol involves injections 1-2 hours before behavioral training to allow for sufficient knockdown during the critical consolidation window.

- Behavioral Testing: Animals are trained on a learning task (e.g., contextual fear conditioning, Morris water maze). Knockdown of a necessary IEG typically impairs long-term memory (LTM) tested 24 hours or more post-training, while leaving short-term memory (STM) intact (tested within a few hours). This double dissociation confirms the role of the IEG in consolidation rather than acquisition or retrieval.

- Validation: In situ hybridization or immunohistochemistry is performed on brain tissue to confirm the reduction in target mRNA or protein levels in the injected region.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Investigating IEGs and Synaptic Tagging

| Reagent / Tool | Function / Target | Key Application in Research |

|---|---|---|

| KN-93 | Reversible CaMKII inhibitor | Dissecting the role of CaMKII in synaptic tag setting during STC protocols [20] |

| STO-609 | CaMKK inhibitor (blocks CaMKIV activation) | Inhibiting the synthesis/availability of PRPs by blocking nuclear signaling to CREB [20] |

| Antisense Oligonucleotides | Sequence-specific mRNA knockdown | Causally linking specific IEGs (e.g., Arc, Zif268) to long-term memory consolidation in vivo [18] |

| Anisomycin / Puromycin | Protein synthesis inhibitors | Establishing the requirement for new protein synthesis in L-LTP and long-term memory; used in STC experiments [15] [19] |

| catFISH (cellular Compartment Analysis of Temporal Activity by FISH) | RNA fluorescence in situ hybridization | Visualizing the temporal dynamics of IEG mRNA (e.g., Arc) transcription and localization in neurons following behavior or stimulation [18] |

| c-Fos-GFP Transgenic Mice | Activity-dependent GFP reporter | Identifying and functionally characterizing neuronal ensembles activated by specific experiences or behaviors [16] |

The interplay between IEGs, synaptic tagging, and local protein synthesis constitutes a core molecular framework for understanding memory consolidation, a process optimized during sleep. The STC hypothesis provides a mechanistic explanation for how the fate of a memory trace is not sealed at the moment of encoding but can be influenced by subsequent experiences and brain states, allowing for the selective stabilization of salient information. The functional and genomic distinction between IEGs and delayed response genes underscores a sophisticated temporal regulation of the plasticity-associated transcriptome.

Future research directions will likely focus on:

- Elucidating the Molecular Identity of the synaptic tag and the complete repertoire of PRPs.

- Understanding Sleep-Specific Modulation: Determining how sleep rhythms (e.g., slow oscillations, spindles) precisely coordinate the dialogue between synapses and the nucleus to enhance tag-PRP interactions.

- Disease Modeling and Drug Discovery: Investigating how disruptions in these fundamental processes contribute to neuropsychiatric disorders (e.g., PTSD, schizophrenia, Alzheimer's disease) characterized by memory dysfunction. The IEG and STC machinery present promising targets for novel therapeutic strategies aimed at modulating maladaptive memory traces or boosting cognitive function.

Within the field of sleep research, a central thesis posits that sleep facilitates memory consolidation through active neural processing. This whitepaper examines the specialized contributions of the two primary sleep stages—slow-wave sleep (SWS) and rapid eye movement (REM) sleep—to this process. While historically, SWS was strongly linked to declarative memory and REM to procedural and emotional memory, contemporary research reveals a more complex, interactive framework. Evidence from human electroencephalography (EEG) studies, targeted memory reactivation (TMR) experiments, and investigations into sleep disorders indicates that these stages operate through distinct yet complementary neurophysiological mechanisms. SWS is characterized by synchronized oscillatory activity that facilitates hippocampo-neocortical dialogue, whereas REM sleep provides a unique neurochemical environment crucial for processing emotional salience and integrating memories. Understanding this specialization is critical for developing therapeutic interventions for memory impairment in aging, neurological disorders, and sleep pathologies.

Neural Signatures and Functional Specialization

The architecture of sleep is defined by distinct neural oscillations that underpin specialized memory functions.

Slow-Wave Sleep (SWS) Mechanisms

SWS, also known as N3 sleep or deep sleep, is dominated by high-amplitude, low-frequency brain waves that create an optimal environment for consolidating declarative memories (facts and events) [5].

- Slow Oscillations (0.5–1 Hz): These represent synchronized neuronal activity alternating between depolarizing "up-states" and hyperpolarizing "down-states," facilitating cortical excitability and synaptic plasticity [5].

- Sleep Spindles (11–16 Hz): These brief, rhythmic bursts originate from the thalamus and are temporally coupled with slow oscillation up-states. Spindles that occur during SWS, as opposed to N2 sleep, are particularly critical for memory consolidation due to this precise temporal coupling [5].

- Hippocampal Sharp-Wave Ripples: High-frequency oscillations (~80-100 Hz) in the hippocampus that coordinate with thalamocortical spindles to facilitate the transfer of memory traces from temporary hippocampal storage to long-term neocortical networks [21].

The tripartite coupling of slow oscillations, spindles, and ripples is now recognized as an active, mechanistic process that orchestrates system-level memory consolidation. This coordinated rhythm enables the selective reactivation of memory traces and promotes synaptic changes necessary for long-term storage [5].

REM Sleep Mechanisms

REM sleep, characterized by desynchronized EEG, muscle atonia, and rapid eye movements, supports distinct aspects of memory processing, particularly for emotional and procedural memories.

- Neurogenesis and Memory Consolidation: Activity in adult-born neurons (ABNs) within the hippocampus during REM sleep is necessary for the consolidation of contextual fear memories, as demonstrated in optogenetic studies [22].

- Emotional Memory Processing: REM sleep has traditionally been associated with the processing of emotionally charged material. However, recent TMR evidence presents a paradox: reactivating emotional stimuli during REM can impair memory, suggesting a potential role in forgetting or emotional tone regulation rather than simple strengthening [23].

- Circadian Regulation: As a circadian-controlled process, REM sleep predominates in the late sleep cycle and may function as a "window-like mechanism" that prepares the brain for the return to consciousness, thereby stabilizing memories before awakening [24].

Table 1: Comparative Neural Oscillations and Their Functions in Memory Consolidation

| Sleep Stage | Primary Oscillations | Neural Origins | Functional Role in Memory |

|---|---|---|---|

| Slow-Wave Sleep | Slow Oscillations (0.5-1 Hz) | Neocortex | Synchronizes hippocampal-neocortical dialogue |

| Sleep Spindles (11-16 Hz) | Thalamus | Facilitates synaptic plasticity & memory transfer | |

| Sharp-Wave Ripples (80-100 Hz) | Hippocampus | Reactivates and strengthens memory traces | |

| REM Sleep | Theta Rhythm (4-10 Hz) | Hippocampus | Supports synaptic plasticity & emotional memory |

| Ponto-Geniculo-Occipital Waves | Brainstem | Potential role in sensory experience integration |

Quantitative Data Synthesis in Memory Consolidation

Research across multiple paradigms provides quantitative evidence for the distinct memory functions of SWS and REM sleep.

SWS and Declarative Memory Enhancement

The integrity of SWS microstructure strongly predicts declarative memory performance. Studies measuring the slow-wave index (a composite of slow-wave duration, amplitude, and frequency) find positive correlations with overnight retention on verbal learning tasks such as the Word Sequence Learning Test (WSLT) [21]. Furthermore, the precise temporal coupling between slow oscillations and spindles is enhanced following intensive declarative learning, with coherence increases observed during post-learning sleep periods [5]. Disruption of SWS, particularly in conditions like obstructive sleep apnea (OSA), quantitatively impairs memory consolidation. The oxygen desaturation index (ODI-3%) and apnea-hypopnea index (AHI) during NREM sleep show significant negative correlations with WSLT-Memory Index Scores [21].

REM Sleep and Emotional Memory

The relationship between REM sleep and emotional memory consolidation reveals complex interactions. One TMR study found that reactivating emotional stimuli during REM sleep unexpectedly increased memory error by 22% for reactivated items versus 11% for non-reactivated items, suggesting an impairing effect [23]. Conversely, the benefit of TMR during SWS for emotional memories was strongly correlated with the product of time spent in REM and SWS (%SWS × %REM), with a Spearman's correlation of rs = 0.66 [23]. This indicates that while REM sleep may not directly strengthen emotional memories, it may interact with SWS in a complementary fashion.

Table 2: Quantitative Relationships Between Sleep Parameters and Memory Performance

| Sleep Parameter | Memory Type | Correlation/Direction | Experimental Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Slow-Wave Index | Declarative (Verbal) | Positive correlation with recall [21] | Polysomnography with Word Sequence Learning Test |

| SO-Spindle Coupling | Declarative | Increased coherence post-learning [5] | EEG during post-learning sleep |

| ODI-3% / AHI in NREM | Declarative | Negative correlation with retention [21] | Obstructive Sleep Apnea patients |

| TMR during REM | Emotional Declarative | 22% vs 11% error (impaired) [23] | Targeted Memory Reactivation paradigm |

| SWS×REM Product | Emotional Declarative | rs = 0.66 with cueing benefit [23] | Targeted Memory Reactivation during SWS |

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Targeted Memory Reactivation (TMR) During Sleep

TMR has emerged as a powerful tool for causally investigating sleep-dependent memory consolidation.

- Protocol Objective: To determine the causal role of specific sleep stages in consolidating declarative and emotional memories [23].

- Stimuli Preparation: Participants encode associative memories (e.g., object-location pairs) paired with distinctive auditory or olfactory cues. Emotional valence is manipulated using International Affective Picture System (IAPS) images or emotionally charged narratives [23].

- Cueing Procedure: During specific sleep stages (SWS or REM), cues associated with a subset of memories are re-presented without awakening the participant. Cue delivery is precisely timed to coincide with specific oscillatory events (e.g., slow oscillation up-states) [23].

- Memory Assessment: Post-sleep recall is tested for both cued and non-cued items. The cueing benefit (CB) is calculated as: %ΔError for non-reactivated - %ΔError for reactivated items, with higher CB indicating better memory for reactivated items [23].

- EEG Monitoring: Concurrent polysomnography records neural responses to cues, including event-related changes in delta/theta power and spindle activity [23].

Slow-Wave Sleep Enhancement Protocols

Several methodologies have been developed to directly modulate SWS activity and assess effects on memory.

- Transcranial Direct Current Stimulation (tDCS): Application of anodal tDCS to frontocortical regions during SWS-rich sleep periods enhances slow-wave activity (<3 Hz) and improves declarative memory retention. Stimulation parameters typically use low currents (0.5-1 mA) applied in a oscillatory pattern synchronized with endogenous slow oscillations [5].

- Closed-Loop Auditory Stimulation: This technique delivers brief auditory stimuli (e.g., clicks) phase-locked to the up-states of endogenous slow oscillations. The protocol enhances the amplitude of slow oscillations and strengthens their coupling with sleep spindles, leading to improved overnight memory consolidation [5].

- Pharmacological Enhancement: Although not detailed in the search results, several studies referenced the use of pharmacological agents to increase slow wave activity or spindle density, thereby enhancing memory for emotional items [23].

Signaling Pathways and System Workflows

The following diagrams visualize the key neural mechanisms and experimental workflows discussed in this whitepaper.

SWS Memory Consolidation Mechanism

SWS Consolidation Pathway

Emotional Memory Processing Across Sleep Stages

Emotional Memory Processing

Targeted Memory Reactivation Workflow

TMR Experimental Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Materials and Methodologies for Sleep-Memory Research

| Tool/Reagent | Primary Function | Research Application |

|---|---|---|

| Polysomnography (PSG) | Records sleep architecture and neural oscillations | Objective measurement of sleep stages (SWS, REM) and EEG features (slow oscillations, spindles) [5] [21] |

| Targeted Memory Reactivation (TMR) | Causal manipulation of memory processing | Reactivating specific memories during sleep with auditory/olfactory cues to test consolidation hypotheses [23] |

| Transcranial Direct Current Stimulation (tDCS) | Non-invasive brain stimulation | Enhancing slow-wave activity during SWS to improve declarative memory consolidation [5] |

| Closed-Loop Auditory Stimulation | Phase-locked sensory stimulation | Boosting slow oscillation amplitude and SO-spindle coupling by delivering sounds at precise oscillation phases [5] |

| Word Sequence Learning Test (WSLT) | Assess declarative memory consolidation | Measuring pre- to post-sleep changes in verbal recall; calculating Memory Index Scores [21] |

| Optogenetic Systems | Cell-type specific neural manipulation | Causally testing role of specific neuron populations (e.g., adult-born neurons) in memory consolidation during REM sleep [22] |

The evidence synthesized in this whitepaper underscores a sophisticated division of labor between SWS and REM sleep in memory consolidation. SWS provides the neural conditions for stabilizing and integrating declarative memories through precisely coupled oscillatory events, while REM sleep contributes to emotional memory processing and system-level integration in ways that are still being elucidated. The emerging paradigm suggests these stages operate as complementary components of a sequential memory processing system rather than serving isolated functions.

Future research should focus on refining non-invasive neuromodulation techniques to selectively enhance the specific oscillatory couplings identified as crucial for memory consolidation. Longitudinal studies examining how age-related declines in sleep architecture contribute to memory impairment could inform therapeutic interventions for neurodegenerative diseases. Furthermore, integrating neuroimaging with high-density EEG could provide deeper insights into the large-scale network dynamics that coordinate sleep-dependent memory processing across the brain. For drug development professionals, these findings highlight promising targets for cognitive enhancement therapies aimed at restoring healthy sleep architecture in clinical populations.

Advanced Tools and Causal Interventions: From Optogenetics to Targeted Stimulation

The study of the neural mechanisms underlying memory consolidation during sleep relies heavily on advanced electrophysiological recording techniques. Polysomnography (PSG) represents the gold standard for comprehensive sleep monitoring, providing a multi-parameter assessment of physiological states during sleep. In parallel, high-density electroencephalography (HD-EEG) has emerged as a powerful tool for investigating the cortical dynamics and functional brain connectivity that support memory processes. These techniques enable researchers to capture the complex neural oscillations and architectural changes that occur throughout sleep cycles, providing critical insights into how memories are processed, stabilized, and integrated overnight.

Within the context of memory consolidation research, these electrophysiological tools have been instrumental in validating the Active Systems Consolidation framework, which posits that coordinated interactions between hippocampal and neocortical networks during sleep facilitate the gradual reorganization of memories. This technical guide examines the capabilities, applications, and methodological considerations of PSG and HD-EEG specifically for investigating these neural mechanisms, with particular emphasis on their utility in basic research and pharmaceutical development for cognitive disorders.

Technical Foundations: PSG vs. HD-EEG

Core Configurations and Capabilities

Polysomnography (PSG) employs a standardized montage typically consisting of 4-6 electroencephalography (EEG) channels supplemented by electrooculography (EOG), electromyography (EMG), and additional physiological sensors for comprehensive sleep assessment. This configuration is designed to classify sleep stages according to established criteria and diagnose sleep disorders through the simultaneous monitoring of brain activity, eye movements, muscle tone, cardiac rhythm, and respiratory effort. The strength of PSG lies in its ability to provide a holistic view of sleep architecture and physiology, making it indispensable for clinical sleep medicine and foundational sleep research [25] [26].

High-Density EEG (HD-EEG) utilizes substantially increased electrode arrays, typically featuring 64 to 256 channels systematically distributed across the scalp according to the 10-10 or 10-5 international systems. This dense spatial sampling dramatically improves spatial resolution compared to standard PSG, enabling more precise source localization and functional connectivity analysis. The technical advantage of HD-EEG is its capacity to capture detailed topographical patterns of neural activity and investigate large-scale brain networks with millisecond temporal resolution, making it particularly valuable for studying the complex cortical dynamics that support cognitive functions, including memory processing during sleep [27].

Table 1: Technical Configuration Comparison between PSG and HD-EEG

| Parameter | Standard PSG | HD-EEG |

|---|---|---|

| Typical EEG Channels | 4-6 electrodes | 64-256 electrodes |

| Supplementary Sensors | EOG, EMG, EKG, respiratory effort, airflow, leg movements | Typically limited to EOG and EMG |

| Spatial Resolution | Limited (∼7 cm inter-electrode distance) | High (∼1-3 cm inter-electrode distance) |

| Temporal Resolution | Millisecond range | Millisecond range |

| Primary Sleep Application | Sleep stage scoring, disorder diagnosis | Sleep oscillation analysis, brain network mapping |

| Memory Research Utility | Architecture-to-memory correlations | Connectivity, source localization, network dynamics |

Performance and Applications in Research

Research comparing these modalities has demonstrated complementary strengths and limitations. A study comparing single-channel forehead EEG to standard PSG found strong overall agreement in sleep stage scoring (kappa = 0.67), with particularly high agreement for REM sleep and combined N2-N3 sleep. However, stage N1 identification showed poor sensitivity (0.2) in the forehead derivation due to the absence of occipital electrodes needed for alpha rhythm detection [26]. This pattern of results highlights the context-dependent utility of different electrode configurations for specific research questions.

The enhanced spatial sampling of HD-EEG provides critical advantages for detecting subtle neurological changes associated with cognitive decline. A 2019 study directly comparing different electrode configurations found that HD-EEG (256-channel) correctly identified the expected weakening of small-world network properties in Alzheimer's Disease patients, while the standard 10-20 system (18-channel) configuration failed to detect these alterations [27]. This demonstrates that HD-EEG offers significantly improved sensitivity for identifying connectomic changes in neurological disorders that affect memory function.

Table 2: Research Applications and Performance Evidence

| Research Application | Optimal Modality | Key Findings from Literature |

|---|---|---|

| Sleep Architecture Analysis | PSG | Gold standard for sleep stage classification according to AASM criteria [26] |

| Sleep-Dependent Memory Consolidation | PSG/HD-EEG | SO-spindle coupling correlates with memory retention across domains [28] |

| Brain Network Changes in Neurodegeneration | HD-EEG | Detects weakened small-world properties in AD/MCI patients missed by standard EEG [27] |

| Nocturnal Event Characterization | Extended-PSG (18-channel EEG) | Combined PSG-EEG diagnosed sleep disorders in 93% and abnormal EEG in 38% of cases with paroxysmal events [29] |

| Longitudinal At-home Monitoring | Single-channel EEG | Substantial agreement with PSG (kappa=0.67) enables multi-night home assessment [26] |

Electrophysiological Signatures of Memory Consolidation

Neural Oscillations and Temporal Coupling

The precise temporal coupling of neural oscillations during non-rapid eye movement (NREM) sleep constitutes a fundamental mechanism for memory consolidation. The hierarchical integration of slow oscillations (SOs, ~1 Hz), sleep spindles (~10-16 Hz), and hippocampal sharp-wave ripples (~80-150 Hz) creates optimal temporal windows for information transfer between hippocampal and neocortical networks. According to the Active Systems Consolidation framework, this triple coupling enables the reactivation of memory traces acquired during wakefulness, facilitating their gradual integration into long-term cortical storage [28].

Slow oscillations originate primarily from neocortical networks and coordinate the rhythmic alternation between periods of neuronal depolarization (up-states) and hyperpolarization (down-states). This synchronization provides a temporal framework that gates the occurrence of thalamocortical sleep spindles, which preferentially cluster during SO up-states. Spindles in turn create favorable conditions for plastic changes in cortical circuits through burst-induced calcium influx in cortical pyramidal cells. Meanwhile, hippocampal sharp-wave ripples, which encompass the reactivation of waking neuronal assemblies, become nested in the troughs of thalamocortical spindles, creating a precise chain of events that supports system-level consolidation [28].

Empirical Evidence from Coupling Studies