The Hidden Wiring: How Anorexia Nervosa Hijacks the Brain

Exploring the neurobiological basis of a misunderstood disorder

Introduction: More Than a Choice

Anorexia nervosa is not a lifestyle choice, a phase, or a simple desire to be thin. It is a severe biologically based brain disorder with one of the highest mortality rates of any psychiatric condition 1 . For decades, society has misunderstood this illness, attributing it to vanity or poor parenting.

However, cutting-edge neuroscience reveals a far more complex picture: anorexia involves distinct genetic vulnerabilities, altered brain structure and function, and fundamental disruptions in how the brain processes reward, punishment, and fear 2 3 .

Key Fact

Anorexia has the highest mortality rate of any psychiatric disorder, estimated at 5-10% per decade

The Faulty Wiring: Brain Circuits Gone Awry

The Genetic Blueprint

Research has consistently demonstrated that anorexia nervosa has a strong heritable component, with genetics accounting for approximately 50-80% of the risk of developing the disorder 1 .

This genetic vulnerability manifests primarily through temperament and personality traits that create a predisposition for developing anorexia. Landmark genetic studies are now underway to identify the specific variations in DNA that contribute to this risk.

The Neural Circuitry of Disorder

Modern neuroimaging techniques have allowed scientists to identify specific brain networks that function differently in people with anorexia nervosa.

| Network Name | Main Brain Regions | Typical Function | Altered Function in AN |

|---|---|---|---|

| Reward System | Ventral striatum, orbitofrontal cortex | Processing pleasure, motivation | Reduced response to food reward |

| Salience Network | Anterior cingulate, insula | Detecting important stimuli | Heightened threat detection from food |

| Default Mode Network | Medial prefrontal cortex, posterior cingulate | Self-referential thinking | Excessive self-focus, rumination |

| Executive Control | Dorsolateral prefrontal cortex | Decision-making, flexibility | Overcontrol of food intake |

Neurochemistry of Starvation: When Hunger Changes the Brain

Dopamine and Serotonin Imbalances

The brain's chemical messaging systems are profoundly affected in anorexia nervosa. Dopamine, a neurotransmitter crucial for reward processing and motivation, appears to be dysregulated.

Similarly, serotonin—a key regulator of mood, anxiety, and appetite—functions abnormally. PET imaging studies have shown higher serotonin 1A-receptor binding in both active anorexia and after recovery, suggesting this may be a trait characteristic rather than a state effect 2 .

Did You Know?

Starvation has an anxiolytic (anxiety-reducing) effect for those with anorexia. Food restriction temporarily reduces anxiety, creating a powerful negative reinforcement cycle that helps explain why anorexia becomes self-perpetuating despite its devastating physical consequences 1 .

The Minnesota Starvation Experiment: A Window into the Starved Mind

Methodology and Purpose

In November 1944, as World War II raged in Europe, physiologist Ancel Keys and psychologist Josef Brozek launched a groundbreaking study at the University of Minnesota to determine the most effective way to rehabilitate famine victims 4 .

The researchers recruited 36 healthy young men from Civilian Public Service units. All were physically and mentally healthy and had expressed a genuine interest in helping with postwar relief efforts.

Research from the mid-20th century provided early insights into starvation effects

Remarkable Results and Analysis

The psychological changes observed during the semi-starvation phase were profound and mirrored many symptoms of anorexia nervosa:

| Psychological Domain | During Semi-Starvation | During Rehabilitation |

|---|---|---|

| Food-Related Thoughts | Intense preoccupation, recipe collecting | Gradual reduction but persistent focus |

| Eating Behaviors | Ritualistic eating, food hoarding | Binge eating, continued rituals |

| Mood | Depression, anxiety, irritability | Slow improvement, emotional volatility |

| Social Functioning | Withdrawal, isolation | Gradual re-engagement |

| Cognitive Function | Poor concentration, narrowed interests | Slow return to baseline |

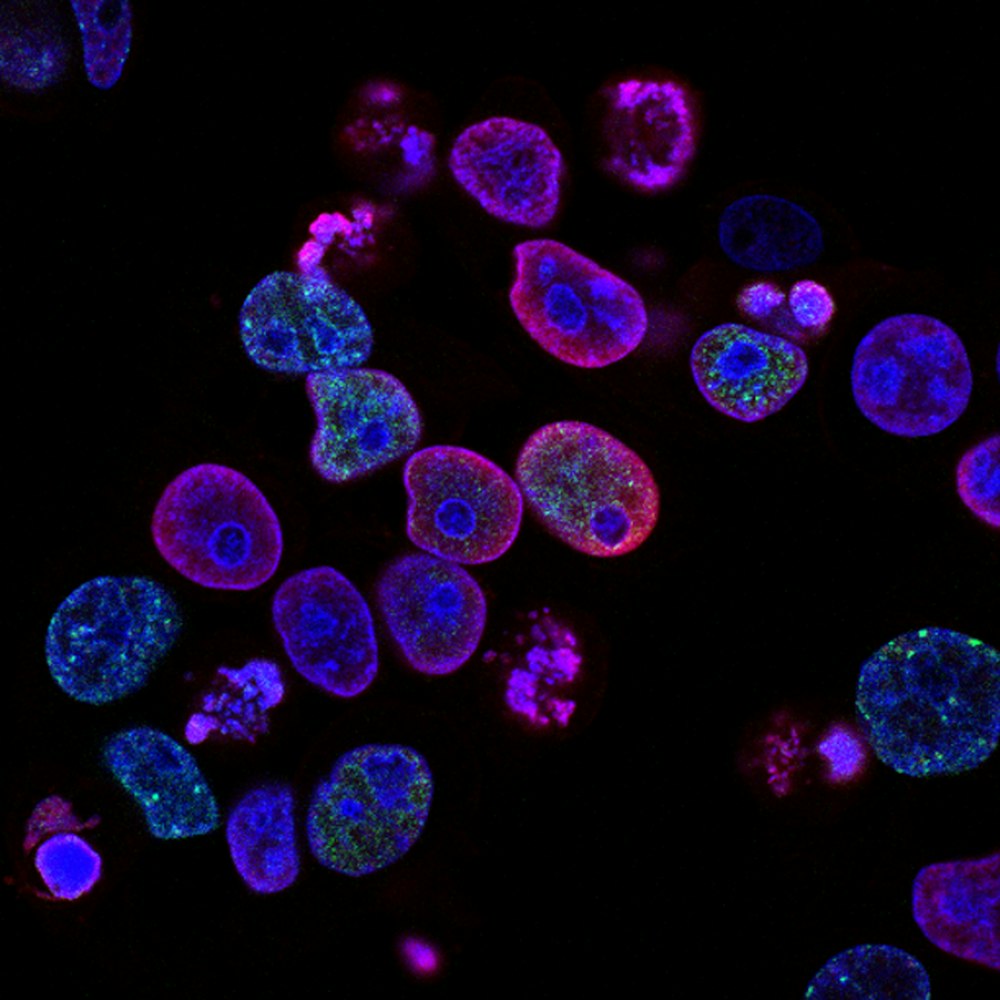

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Understanding the neurobiology of anorexia requires sophisticated tools and techniques. Researchers use a variety of specialized approaches to unravel the complex brain changes associated with the disorder.

Structural MRI

Measures gray and white matter volume to identify reduced brain volume in starvation and partial reversal with weight restoration.

fMRI

Maps brain activity during tasks to reveal altered reward processing and heightened fear response to food.

Genetic Analysis

Identifies risk genes and heritability patterns to understand specific vulnerability genes associated with anorexia.

Beyond Starvation: Future Directions and Treatment Implications

The neurobiological understanding of anorexia is already transforming treatment approaches. New interventions are focusing on targeting the underlying neurobiology rather than just the surface symptoms.

Innovative Neurobiologically-Informed Treatment

A five-day program that teaches adults with anorexia and their supports about the genetic and brain basis of the disorder 1 .

Promising Approaches

- Neuromodulation techniques

- Cognitive remediation therapy

- Family-based treatments

- Targeted medications

Treatment Effectiveness

Conclusion: Toward a Neurobiological Understanding

The emerging neurobiological research on anorexia nervosa paints a complex picture of a brain disorder with strong genetic underpinnings, distinct neurostructural and neurofunctional abnormalities, and altered neurochemical functioning.

Rather than being driven primarily by social factors or personal choices, anorexia appears to stem from biological vulnerabilities that interact with environmental triggers to produce the devastating illness we see.

While much remains to be discovered, the neurobiological approach offers real hope for developing better treatments and ultimately preventing this devastating disorder.

References

References will be listed here in the final version.