Technical Challenges in Addiction Neurocircuitry Analysis: From Foundational Models to Clinical Translation

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of the technical challenges in addiction neurocircuitry research, addressing the needs of researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals.

Technical Challenges in Addiction Neurocircuitry Analysis: From Foundational Models to Clinical Translation

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of the technical challenges in addiction neurocircuitry research, addressing the needs of researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals. It explores the foundational framework of addiction neurocircuitry, particularly the three-stage cycle model encompassing binge/intoxication, withdrawal/negative affect, and preoccupation/anticipation stages. The content examines methodological advances including computational modeling, neuroimaging, and neuromodulation techniques, while addressing troubleshooting challenges such as individual variability, model limitations, and technical barriers in brain stimulation. Finally, it evaluates validation approaches and comparative efficacy of different analytical methods, offering insights for future biomedical research and clinical application development.

Deconstructing the Addiction Cycle: Core Neurocircuitry Frameworks and Conceptual Challenges

FAQs: Core Neurocircuitry Framework

What is the three-stage addiction cycle and its associated neurocircuitry? The three-stage addiction cycle is a heuristic model that describes addiction as a chronic, relapsing disorder characterized by a spiral of impulsivity and compulsivity. The stages are binge/intoxication, withdrawal/negative affect, and preoccupation/anticipation. Each stage is mediated by specific, though overlapping, neurocircuits [1].

- Binge/Intoxication: This stage is focused on the pleasurable effects of the drug and is primarily associated with the ventral tegmental area (VTA) and the ventral striatum (including the nucleus accumbens), key components of the brain's dopamine system [1].

- Withdrawal/Negative Affect: This stage occurs when drug access is prevented and is characterized by a negative emotional state. It is primarily mediated by the extended amygdala [1].

- Preoccupation/Anticipation (Craving): This stage involves the craving for the drug and the loss of control over drug-seeking. It engages a distributed network including the orbitofrontal cortex-dorsal striatum, prefrontal cortex, basolateral amygdala, hippocampus, and insula [1].

What are the common functional connectivity findings across Substance Use Disorders (SUDs)? A 2025 meta-analysis of resting-state functional magnetic resonance imaging (rs-fMRI) studies identified consistent disruptions within the cortical-striatal-thalamic-cortical circuit across various SUDs [2]. Key findings are summarized in the table below.

Table 1: Common Resting-State Functional Connectivity (rsFC) Alterations in SUD [2]

| Seed Region | Hyperconnectivity Observed With | Hypoconnectivity Observed With |

|---|---|---|

| Anterior Cingulate Cortex (ACC) | Inferior Frontal Gyrus, Lentiform Nucleus, Putamen | — |

| Prefrontal Cortex (PFC) | Superior Frontal Gyrus, Striatum | Inferior Frontal Gyrus |

| Striatum | Superior Frontal Gyrus | Median Cingulate Gyrus |

| Thalamus | — | Superior Frontal Gyrus, dorsal ACC, Caudate Nucleus |

| Amygdala | — | Superior Frontal Gyrus, ACC |

What are the key dopaminergic alterations observed in human addiction? Positron Emission Tomography (PET) studies have consistently shown lower availability of striatal dopamine D2/3 receptors (D2/3R) in individuals with cocaine, methamphetamine, alcohol, and opioid use disorders compared to healthy controls [3]. This hypodopaminergic state is associated with negative affect, craving, and reduced motivation for natural rewards [3].

Troubleshooting Guides & Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Targeting Dissociable Neurocircuits with Deep TMS

This protocol details a method to modulate the two key prefrontal-striatal circuits implicated in AUD, providing a model for circuit-specific intervention [4].

- Objective: To examine the capacity of two distinct theta-burst dTMS protocols to recalibrate the weakened dlPFC (executive control) and heightened vmPFC (limbic control) pathways in individuals with Alcohol Use Disorder (AUD) [4].

- Design: Randomized, single-blind, sham-controlled crossover trial [4].

- Participants: 30 adults (aged 18-49) with moderate to severe AUD [4].

- Interventions:

- Active iTBS to dlPFC: Intermittent TBS is applied using an H-coil to increase neuronal excitability in the weakened dorsolateral prefrontal cortex pathway.

- Active cTBS to vmPFC: Continuous TBS is applied using an H-coil to decrease neuronal excitability in the heightened ventromedial prefrontal cortex pathway.

- Sham Control: A sham condition is used to control for non-specific effects of stimulation.

- Outcome Measures:

- Primary: Change in effective connectivity within targeted circuits, assessed via spectral Dynamic Causal Modeling (spDCM) of resting-state fMRI data [4].

- Secondary: Changes in cognitive tests of executive control and decision-making [4].

- Exploratory: Laboratory measures of craving, and longitudinal tracking of daily craving and alcohol consumption over 90 days [4].

Challenge: Inconsistent rs-fMRI Findings Across SUD Studies

Symptoms: Reported functional connectivity changes for the same seed region (e.g., striatum) vary significantly between studies, showing both increased and decreased connectivity with frontal regions [2].

Diagnosis & Solution: The inconsistency often stems from heterogeneity in study parameters. Table 2: Troubleshooting Inconsistent rs-fMRI Findings in SUD Research

| Potential Cause | Impact on Results | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Heterogeneous SUD Populations | Varying substances of abuse, stages of addiction, and comorbidities introduce noise. | Implement strict participant stratification by primary substance, dependence severity, and abstinence duration. Conduct substance-specific meta-analyses [2]. |

| Small Sample Sizes | Underpowered studies produce unreliable and non-replicable findings. | Prioritize large-scale, collaborative studies. Use meta-analytic techniques (e.g., SDM-PSI) to pool data from multiple studies for increased power [2]. |

| Varied Analytical Methodologies | Differences in preprocessing pipelines, seed placement, and statistical thresholds affect outcomes. | Adopt and publish standardized, consensus-based preprocessing and analytical protocols. Use validated, anatomical or functional seeds. |

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 3: Key Reagents and Resources for Addiction Neurocircuitry Research

| Resource / Reagent | Application / Function |

|---|---|

| Deep TMS (dTMS) H-coil | Enables non-invasive modulation of deeper cortical and subcortical nodes (e.g., vmPFC, striatum) compared to traditional figure-eight coils, allowing direct targeting of addiction-relevant circuits [4]. |

| Spectral Dynamic Causal Modeling (spDCM) | A computational method applied to fMRI data to infer the directed (effective) connectivity between brain regions, quantifying how one region influences another [4]. |

| Theta-Burst Stimulation (TBS) | A patterned form of rTMS that mimics endogenous brain rhythms. Intermittent (iTBS) increases cortical excitability, while continuous (cTBS) decreases it, allowing bidirectional circuit control [4]. |

| GLP-1 Receptor Agonists (e.g., Semaglutide) | A class of drugs emerging as a potential new therapeutic. Preclinical and early clinical trials suggest they modulate neurobiological pathways underlying addictive behaviors and may reduce alcohol use and craving [5]. |

| Ultrahigh-Resolution fMRI | An emerging technology capable of resolving activations in individual cortical layers, promising a more nuanced understanding of circuit-specific dopaminergic signaling [3]. |

| Neuromelanin-Sensitive MRI | A non-invasive proxy for measuring dopamine function and metabolism in the substantia nigra, providing insights into the integrity of the dopaminergic system in vivo [3]. |

Emerging Frontiers & Novel Signaling Pathways

The Role of GLP-1 in Addiction Glucagon-Like Peptide-1 Receptor Agonists (GLP-1RAs), used for diabetes and obesity, are under investigation for SUD. The pathway involves GLP-1R activation within the central nervous system, which is thought to curb addictive behaviors by modulating reward-related neurocircuitry. Early studies show:

- AUD: Low-dose semaglutide reduced alcohol self-administration and craving in a randomized controlled trial [5].

- Opioid Use Disorder (OUD): Rodent models show GLP-1RAs reduce self-administration of heroin, fentanyl, and oxycodone, and reduce reinstatement of drug-seeking [5].

- Tobacco Use Disorder: Preclinical data indicate reduced nicotine self-administration, with initial clinical trials suggesting potential for reducing cigarette use [5].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What are the primary functions of the four key neural networks in addiction neurocircuitry? These regions form a interconnected circuit that drives different stages of the addiction cycle [6]. The Ventral Tegmental Area (VTA) is crucial for initial drug reward and reinforcement through dopamine release [7] [8]. The Ventral Striatum (particularly the Nucleus Accumbens) is the hub for integrating reward and motivation signals, mediating the acute reinforcing effects of drugs [9] [6]. The Extended Amygdala (including central amygdala, bed nucleus of stria terminalis) becomes critical during withdrawal, generating negative affect and stress via systems like CRF and norepinephrine [10] [6]. The Prefrontal Cortex (PFC), especially orbitofrontal, anterior cingulate, and dorsolateral regions, governs executive function; its dysfunction leads to loss of control over drug intake, compulsivity, and impaired decision-making [11] [6].

Q2: What rodent behavioral models are best for studying specific aspects of substance use disorder? Different models recapitulate specific behavioral criteria of Substance Use Disorder. The table below summarizes the primary application and neural substrates of common models.

Table 1: Rodent Behavioral Models for Substance Use Disorder Research

| Behavioral Model | Primary Addictive Phenomena Modeled | Key Neural Circuits Involved | Experimental Readout |

|---|---|---|---|

| Conditioned Place Preference (CPP) [7] | Contextual reward learning & relapse | VTA, Ventral Striatum [7] | Time spent in drug-paired context vs. neutral context |

| Drug Self-Administration [7] | Escalated intake, motivation, relapse | VTA, Ventral Striatum, Dorsal Striatum, PFC [7] [9] | Number of operant responses (e.g., lever presses) for drug infusion |

| Behavioral Sensitization [7] | Progressive neuroadaptations to repeated drug exposure | VTA, Ventral Striatum [7] | Increase in drug-induced locomotor activity over repeated injections |

| Cued Reinstatement [7] [6] | Drug relapse triggered by cues | Ventral Striatum, Basolateral Amygdala, PFC [6] | Resumption of drug-seeking in response to a conditioned cue |

Q3: How do dopamine circuits functionally diverge in addiction-like behaviors? Mesostriatal (VTA to Ventral Striatum) and nigrostriatal (SNc to Dorsal Striatum) dopamine circuits have dissociable roles. The table below outlines their distinct contributions.

Table 2: Functional Roles of Dopamine Circuits in Addiction-like Behaviors

| Circuit Feature | Mesostriatal Pathway (VTA → Ventral Striatum) | Nigrostriatal Pathway (SNc → Dorsal Striatum) |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Behavioral Role | Motivational "pull"; goal-directed behavior, cue-reward learning [8] | Behavioral "push"; habit formation, movement invigoration [8] |

| Role in Addiction | Initial drug reward, positive reinforcement, cue-induced craving [8] [6] | Transition to compulsive, habitual drug use [8] |

| Relevant SUD Criteria | Impaired control (escalated use) [8] | Risky use, social impairment (perseveration despite harm) [8] |

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem 1: Lack of Cell-Type Specificity in Circuit Manipulation

Issue: Traditional lesions or pharmacological manipulations affect multiple neuronal populations, confounding interpretation of results from dense, heterogeneous regions like the VTA [7].

Solution: Utilize modern, cell-type-specific tools.

- Recommended Technique: Optogenetics or Chemogenetics (DREADDs).

- Sample Protocol (DREADDs):

- Stereotaxic Injection: Inject a Cre-inducible viral vector (e.g., AAV-hSyn-DIO-hM3D(Gq)-mCherry) into the target region (e.g., VTA) of transgenic Cre-driver mice (e.g., DAT-Cre for dopamine neurons) [9].

- Incubation: Allow 3-4 weeks for viral expression.

- Administration: Administer the designer ligand (e.g., CNO, 1-3 mg/kg, i.p.) prior to behavioral testing.

- Validation: Confirm expression and functionality post-hoc via immunohistochemistry and/or in vivo electrophysiology.

Problem 2: Differentiating Direct vs. Indirect Pathway Activity in the Striatum

Issue: The striatum's direct (dMSNs) and indirect (iMSNs) pathway neurons are intermingled, making selective study difficult [9].

Solution: Leverage pathway-specific biomarkers and tools.

- Recommended Technique: Pathway-specific transgenic mice or FISH.

- Identification Guide:

- Experimental Application: Use ex vivo electrophysiology in brain slices from D1-Cre or D2-Cre mice to measure drug-induced synaptic plasticity specific to each pathway [12].

Problem 3: Measuring Compulsive-like Behavior in Rodents

Issue: Simple drug self-administration does not capture the core addiction criterion of "use despite adverse consequences" [7].

Solution: Implement progressive ratio or punishment-based schedules of reinforcement.

- Recommended Assay: Punished Drug Seeking.

- Detailed Protocol:

- Stable Self-Administration: Train rats to self-administer a drug (e.g., cocaine, 0.75 mg/kg/infusion, 2h sessions) on a fixed-ratio 1 (FR1) schedule until stable intake is achieved.

- Introduce Aversion: In subsequent test sessions, deliver a mild footshock (e.g., 0.2-0.3 mA, 0.5s duration) contingent upon drug infusion. This can be done on all infusions or on a subset.

- Quantify Compulsion: The proportion of animals that continue to self-administer the drug despite the footshock is considered to exhibit a compulsive, addiction-like phenotype [6]. Compare the number of infusions earned on punishment days to baseline.

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Addiction Neurocircuitry Studies

| Reagent / Tool | Primary Function | Example Application |

|---|---|---|

| Cre-driver Mouse Lines (e.g., DAT-Cre, D1-Cre, D2-Cre) | Enables genetic access to specific neuronal populations [9] | Targeting dopamine neurons or specific striatal pathways for manipulation or imaging. |

| Chemogenetic Tools (DREADDs) | Chemically remote control of neuronal activity [9] | Manipulating specific circuit elements during behavioral tests without implanted hardware. |

| Channelrhodopsin (ChR2) & Archaerhodopsin (ArchT) | Precise optogenetic activation or inhibition of neurons with light [12] | Establishing causal links between circuit activity and behavior with millisecond precision. |

| AAV Vectors (e.g., AAV5, AAV9) | Efficient delivery of genetic constructs to the brain [9] | Expressing opsins, DREADDs, or sensors in a region- and cell-type-specific manner. |

| Fiber Photometry Systems | Recording population-level calcium or neurotransmitter dynamics in vivo [8] | Measuring real-time activity of a defined neural population during drug-related behaviors. |

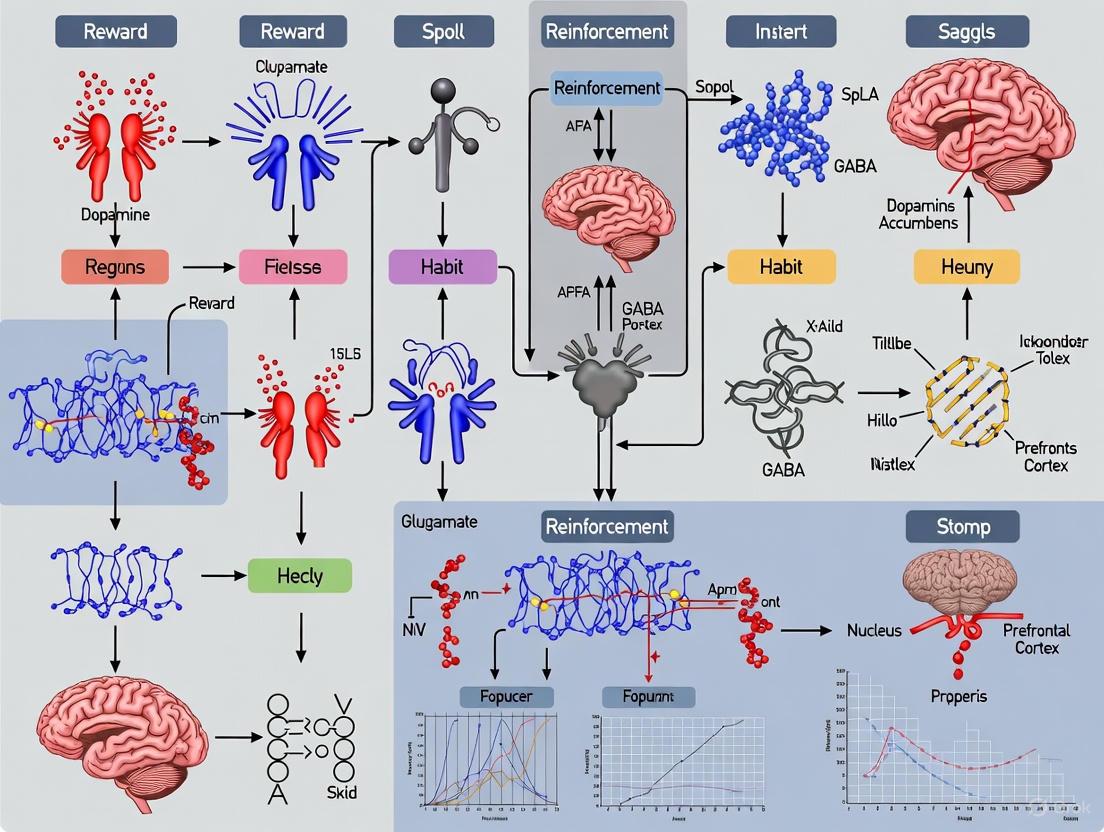

Visualizations: Key Addiction Neurocircuitry

The Three-Stage Addiction Cycle

Striatal Circuitry in Addiction

Prefrontal Cortex Dysfunction in Addiction (iRISA Model)

Addiction is a chronic relapsing disorder characterized by a compulsive pattern of drug seeking and use, which can be understood through the framework of a three-stage cycle: binge/intoxication, withdrawal/negative affect, and preoccupation/anticipation (craving) [13] [6]. Each stage is mediated by specific neurotransmitter systems acting within distinct brain circuits, and their dysregulation presents key technical challenges for researchers aiming to dissect these mechanisms [13] [14].

The core neurocircuitry involves the basal ganglia (critical for reward and habit formation in the binge/intoxication stage), the extended amygdala (central to the negative emotional state of withdrawal), and the prefrontal cortex (responsible for the executive function deficits and craving seen in the preoccupation/anticipation stage) [13]. The following diagram illustrates the interplay of these circuits and neurotransmitters across the addiction cycle.

Troubleshooting Guides: Key Neurotransmitter Systems

This section addresses common experimental challenges in studying the primary neurotransmitter systems implicated in addiction.

FAQ: Investigating the Mesolimbic Dopamine System

Q: What is the primary function of dopamine in addiction? A: Dopamine in the mesolimbic pathway (VTA to NAc) is crucial for the rewarding and reinforcing effects of drugs during the binge/intoxication stage. All major drugs of abuse directly or indirectly increase extracellular dopamine in the NAc, reinforcing drug-taking behavior [15] [16]. Fast and steep dopamine release is associated with the subjective "high" [13].

Q: My microdialysis data shows inconsistent dopamine release across different drug classes. Is this expected? A: Yes. While all addictive drugs increase NAc dopamine, they achieve this through distinct primary molecular targets [16]. For example, opioids do so by disinhibiting VTA dopamine neurons via GABA interneurons, while stimulants like cocaine directly block the dopamine transporter (DAT). Your results should align with the specific mechanism of the drug you are studying. Refer to Table 1 for details.

Q: How can I model the transition from goal-directed to habitual drug seeking? A: This transition involves a shift in the locus of dopaminergic control from the ventral striatum (NAc) to the dorsal striatum. Experimental designs should incorporate extended access self-administration protocols and use neural activity markers or receptor quantification to track this ventral-to-dorsal progression [13] [6].

FAQ: Probing the Opioid Peptide System

Q: Besides their own rewarding effects, how do opioid peptides influence other drug addictions? A: The endogenous opioid system, particularly mu-opioid receptors (MOR), critically modulates the rewarding properties of non-opioid drugs like alcohol, cocaine, and nicotine [16]. For example, alcohol consumption has been shown to induce endogenous opioid release in the human orbitofrontal cortex and NAc [13].

Q: Why does the opioid antagonist naltrexone show variable efficacy in clinical trials for alcoholism? A: This is a key translational challenge. Preclinical studies reliably show naltrexone reduces alcohol intake, but human clinical outcomes can be influenced by compliance issues and genetic variability in the opioid system [15]. Technical considerations for your research should include investigating individual differences in MOR expression or function.

FAQ: Analyzing the Brain Stress Systems (CRF and Dynorphin)

Q: What is the primary role of CRF and dynorphin in the addiction cycle? A: Corticotropin-releasing factor (CRF) and dynorphin are key mediators of the negative emotional state of withdrawal [13] [14]. During the withdrawal/negative affect stage, CRF systems in the extended amygdala become hyperactive, while dynorphin (a kappa-opioid receptor agonist) exerts aversive effects. This "dark side of addiction" drives negative reinforcement—taking the drug to relieve this dysphoric state.

Q: My CRF measurements in the amygdala are highly variable during withdrawal. What factors should I control for? A: Key factors include the duration of drug access (limited vs. extended), the time point of measurement after cessation, and environmental conditions like stress. The stress response is dynamic, and these factors significantly influence the magnitude of CRF and dynorphin system engagement [13].

FAQ: Assessing the Glutamate System and Executive Function

Q: How does glutamate contribute to craving and relapse? A: In the preoccupation/anticipation stage, glutamatergic projections from the prefrontal cortex to the NAc and extended amygdala become dysregulated [13] [14]. This is thought to underpin the intense craving and compromised executive control that can trigger relapse. A key mechanism is the incubation of craving, mediated by changes in AMPA receptor subunits in the NAc [6].

Q: What techniques can I use to study these prefrontal glutamate projections? A: Optogenetic or chemogenetic manipulation of specific prefrontal glutamatergic pathways during cue-induced reinstatement tests in animal models is a powerful approach. In humans, MR spectroscopy can measure glutamate levels, while functional connectivity MRI can assess the integrity of these circuits [13] [17].

The following tables consolidate key quantitative neurochemical changes and drug mechanisms to aid experimental design and data interpretation.

Table 1: Neurotransmitter Dynamics Across the Addiction Cycle [13]

| Addiction Stage | Neurotransmitter/Neuromodulator | Direction of Change |

|---|---|---|

| Binge/Intoxication | Dopamine | Increase |

| Opioid Peptides | Increase | |

| Serotonin | Increase | |

| GABA | Increase | |

| Withdrawal/Negative Affect | Corticotropin-Releasing Factor (CRF) | Increase |

| Dynorphin | Increase | |

| Norepinephrine | Increase | |

| Dopamine | Decrease | |

| Serotonin | Decrease | |

| Neuropeptide Y | Decrease | |

| Preoccupation/Anticipation | Glutamate | Increase |

| Dopamine | Increase | |

| Corticotropin-Releasing Factor (CRF) | Increase |

Table 2: Primary Neurotransmitter Mechanisms of Major Drugs of Abuse [15] [16]

| Drug Class | Primary Molecular Target | Net Effect on Reward Pathway |

|---|---|---|

| Opioids | Mu-Opioid Receptor (MOR) agonist | ↑DA in NAc (via disinhibition of VTA GABA neurons) |

| Stimulants | Cocaine: DAT blockerAmphetamines: DAT reversal/VMAT2 blocker | ↑DA in NAc (directly increases synaptic DA) |

| Alcohol | Multiple: enhances GABA-A, inhibits NMDA, ↑MOR | ↑DA in NAc (complex indirect modulation) |

| Nicotine | Nicotinic Acetylcholine Receptor (nAChR) agonist | ↑DA in NAc (direct activation of VTA DA neurons) |

| Cannabis | Cannabinoid CB1 Receptor agonist | Modulates GABA/Glu release, influencing VTA DA activity |

Standard Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Intracranial Self-Stimulation (ICSS) to Measure Brain Reward Function

- Purpose: To assess the hedonic state ("reward threshold") in animal models, particularly during drug withdrawal, which is a key marker of the withdrawal/negative affect stage [13].

- Methodology:

- Surgery: Implant a stimulating electrode into the medial forebrain bundle (MFB) in rats or mice.

- Training: Train subjects to press a lever to receive a brief electrical stimulus to the MFB.

- Threshold Determination: Use a psychophysical method (e.g., the "discrete-trial current-intensity" procedure) to determine the minimum current intensity required for the animal to perceive the stimulus as rewarding.

- Testing: Measure reward thresholds at baseline, during chronic drug administration, and at various time points during withdrawal. Elevated thresholds indicate a state of anhedonia (diminished reward function) [13].

- Technical Note: This model directly links to the human experience of dysphoria and anhedonia during abstinence.

Protocol 2: Drug Self-Administration and Reinstatement

- Purpose: The gold standard for modeling drug taking, seeking, and relapse in animals [6].

- Methodology:

- Surgery: Implant an intravenous catheter for drug delivery.

- Acquisition: Train animals to perform an operant response (e.g., nose-poke or lever-press) to receive a drug infusion, typically paired with a conditioned cue (light or tone).

- Extinction: Remove the drug and associated cues. The operant response no longer results in drug delivery.

- Reinstatement Test: Trigger drug-seeking behavior (measured as responses on the previously active lever) by:

- A priming dose of the drug (drug-induced reinstatement).

- Presentation of the drug-associated cue (cue-induced reinstatement).

- Exposure to a stressor (stress-induced reinstatement).

- Technical Note: This protocol effectively models the three stages of the addiction cycle and is ideal for testing potential anti-craving or relapse-prevention medications [13].

Key Signaling Pathways

The transition to addiction involves complex intracellular adaptations within the defined neurocircuitry. The diagram below outlines a generalized signaling cascade triggered by chronic drug exposure, leading to transcriptional changes that underlie long-term neuroplasticity.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Addiction Neurobiology

| Reagent / Tool | Primary Function / Target | Example Application in Addiction Research |

|---|---|---|

| Dopamine Receptor Antagonists (e.g., SCH 23390 for D1, Eticlopride for D2) | Pharmacological blockade of dopamine receptors. | Used to dissect the role of specific DA receptor subtypes in drug reward and reinforcement in self-administration models [13]. |

| Opioid Receptor Antagonists (e.g., Naltrexone, Naloxone) | Broad opioid receptor blockade. | To test the involvement of endogenous opioid systems in the rewarding effects of alcohol, opioids, and other drugs [15] [16]. |

| CRF Receptor Antagonists (e.g., R121919, CP-154,526) | Blockade of CRF1 receptors. | Used to investigate the role of brain stress systems in withdrawal-induced anxiety and stress-induced reinstatement of drug seeking [13] [14]. |

| Kappa-Opioid Receptor Agonists/Antagonists (e.g., U50,488 (agonist), Nor-BNI (antagonist)) | Modulation of the dynorphin/KOR system. | To probe the aversive, stress-like effects of dynorphin during withdrawal and its impact on drug seeking [13]. |

| AMPA/NMDA Receptor Modulators (e.g., NBQX for AMPA, MK-801 for NMDA) | Glutamate receptor blockade. | To study the role of glutamatergic transmission in the prefrontal-striatal-amygdala circuits underlying craving and relapse [13] [6]. |

| DAT/SERT Inhibitors (e.g., GBR 12909 for DAT, Citalopram for SERT) | Selective blockade of monoamine transporters. | To isolate the effects of specific monoamine systems in psychostimulant reward and toxicity [16]. |

FAQs: Core Neurocircuitry Concepts

Q1: What is the fundamental neuroanatomical shift observed in the transition to addiction?

The transition is characterized by a ventral to dorsal striatal shift in control over drug-seeking behavior. Initially, goal-directed actions are driven by the ventral striatum (VS), particularly the nucleus accumbens, which processes reward and incentive salience. As addiction progresses, control shifts to the dorsal striatum (DS), which mediates habitual and compulsive behaviors. This represents a move from impulsive to compulsive drug use [1] [13] [18].

Q2: How are "impulsivity" and "compulsivity" defined in the context of addiction stages?

- Impulsivity: A predisposition toward rapid, unplanned reactions to stimuli without regard for negative consequences. This dominates the early stages of addiction and is largely associated with positive reinforcement mechanisms [1] [13].

- Compulsivity: The manifestation of perseverative, repetitive actions that are excessive and inappropriate. This dominates the later stages and is largely associated with negative reinforcement—performing the behavior to reduce a negative emotional state [1] [13].

Q3: What are the key neurotransmitter systems involved in this transition?

Different neurotransmitter systems are dysregulated across the three stages of the addiction cycle [13]:

Table: Key Neurotransmitter Changes in the Addiction Cycle

| Addiction Stage | Neurotransmitter | Direction of Change |

|---|---|---|

| Binge/Intoxication | Dopamine | Increase [13] |

| Opioid Peptides | Increase [13] | |

| Withdrawal/Negative Affect | Dopamine | Decrease [13] |

| Corticotropin-Releasing Factor (CRF) | Increase [13] | |

| Dynorphin | Increase [13] | |

| Preoccupation/Anticipation | Glutamate | Increase [13] |

Q4: What functional connectivity patterns distinguish ventral and dorsal striatum in addiction?

Resting-state functional connectivity (rsFC) studies reveal distinct patterns. In cocaine dependence, for example:

- Ventral Striatum (VS): Shows increased connectivity with the left inferior frontal cortex (IFC) and decreased connectivity with the hippocampus. These changes are correlated with higher impulsivity scores and recent cocaine use severity [19].

- Dorsal Striatum (DS): Shows increased connectivity with the orbitofrontal cortex (OFC), a pattern less directly correlated with impulsivity or recent use, potentially indicating a shift towards habitual processing [19].

Troubleshooting Guides & Experimental Protocols

Guide 1: Measuring Ventral-to-Dorsal Striatal Shifts Using Resting-State fMRI

Challenge: Inconsistent or weak findings when attempting to replicate ventral-to-dorsal shifts in human cohorts.

Solutions:

- Precise Seed Definition: Use well-validated, standardized atlases (e.g., Harvard-Oxford Subcortical Atlas) to define ventral (e.g., nucleus accumbens) and dorsal (e.g., caudate, putamen) striatal seeds for functional connectivity analysis. Avoid using small, arbitrary spherical seeds [19] [18].

- Cohort Stratification: Do not treat all individuals with a substance use disorder as a single group. Stratify your cohort based on addiction severity, duration of use, or behavioral measures of impulsivity/compulsivity to detect stage-specific connectivity changes [19].

- Control for Confounds: Rigorously account for age, sex, smoking status, and other substance use (e.g., alcohol) in your statistical models, as these can significantly influence functional connectivity measures [19].

Detailed Protocol: Seed-Based Functional Connectivity Analysis [19] [18]

- Data Acquisition: Acquire high-resolution T1-weighted anatomical and resting-state BOLD fMRI images on a 3T scanner (e.g., multi-band sequence to increase temporal resolution).

- Preprocessing: Process data using standard pipelines (e.g., fMRIPrep, CONN). Steps should include realignment, slice-time correction, normalization to standard space (e.g., MNI), and smoothing with an isotropic Gaussian kernel.

- Seed Placement: Define seed regions of interest (ROIs) for the Ventral Striatum and Dorsal Striatum.

- Time-Series Extraction: For each subject, extract the mean BOLD time series from each seed ROI.

- Connectivity Calculation: Compute the temporal correlation (e.g., Pearson's correlation) between the seed time series and the time series of every other voxel in the brain.

- Statistical Analysis: Convert correlation coefficients to Z-scores using Fisher's transformation. Compare Z-scores between patient and control groups using a general linear model (e.g., in SPM, FSL), including appropriate covariates.

Guide 2: Modeling the Transition in Animal Studies

Challenge: Designing an animal model that effectively captures the progression from voluntary, impulsive drug use to compulsive drug-seeking.

Solutions:

- Use Extended Access Models: Move beyond short-access (e.g., 1-2 hour) self-administration sessions. Implement "long-access" models (e.g., 6+ hours) which promote escalation of intake, a key feature of the transition to addiction [1] [13].

- Incororate Compulsion-Like Measures: Design protocols that measure drug-seeking despite adverse consequences. This can be done by pairing drug infusions with a punishing stimulus (e.g., a mild footshock) and observing which animals continue to self-administer, indicating compulsivity [13].

- Probe Cue-Induced Reinstatement: After extinction of drug-seeking behavior, re-present drug-associated cues. The degree of reinstatement is a model of craving and relapse, key elements of the "preoccupation/anticipation" stage [1] [13].

Guide 3: Targeting Specific Neurocircuits for Intervention

Challenge: Translating neurocircuitry findings into potential interventions.

Solutions & Protocol: Computational Modeling for Intervention Prediction [20] Recent research uses biophysical models of frontostriatal circuits to simulate "virtual interventions" and predict the most effective targets for restoring healthy dynamics.

- Model Construction: Develop a computational model of the interacting ventromedial (VS-OFC) and dorsolateral (DS-lateral PFC) circuits based on known anatomy and neurotransmitter actions.

- Parameter Estimation: Fit the model to empirical resting-state fMRI data from individuals with addiction (or OCD as a model of compulsivity) and healthy controls to identify disease-specific parameters (e.g., strengths of neural couplings) [20].

- Virtual Intervention Simulation: Systematically simulate changes to the model parameters (e.g., increasing dorsolateral cortico-striatal coupling while decreasing ventromedial coupling) to see which combination best restores the functional connectivity pattern observed in healthy controls [20].

- Validation: Test the model's predictions using longitudinal data, correlating simulated parameter changes with actual fluctuations in symptom severity over time. This approach can prioritize targets for neuromodulation therapies like TMS [20].

Signaling Pathways & Neurocircuitry Diagrams

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table: Essential Reagents and Models for Investigating Striatal Transitions

| Item/Category | Function/Description | Example Application |

|---|---|---|

| Long-Access Self-Administration Model | An animal model where subjects have extended (6+ hrs) daily access to a drug, leading to escalated intake and compulsive-like seeking. | Modeling the transition from controlled to uncontrolled drug use; studying escalation neurobiology [13]. |

| Dopamine Receptor Antagonists | Pharmacological agents that block dopamine receptors (e.g., D1-like and D2-like receptor antagonists). | Local microinfusions to dissect the role of specific striatal subregion dopamine signaling in drug-seeking habits [13]. |

| Resting-State fMRI | A non-invasive neuroimaging technique that measures spontaneous brain activity to infer functional connectivity between regions. | Identifying hyper- and hypoconnectivity between ventral/dorsal striatum and cortical regions in human addiction [19] [18]. |

| Circuit-Specific Optogenetics | A technique using light to control the activity of genetically defined neurons in specific brain pathways. | Causally testing the role of specific VTA→VS or VTA→DS pathways in drug reward and relapse [1]. |

| Dynamic Causal Modeling (DCM) | A computational method for inferring effective connectivity (directed influence) between brain regions from fMRI data. | Modeling the directional influence between PFC and striatum and how it is altered in addiction [18] [20]. |

Troubleshooting Guides

Guide 1: Troubleshooting Target Identification in Addiction Neurocircuitry

Problem: Inconsistent results when trying to identify key brain targets for therapeutic neuromodulation in addiction.

Solution: Employ a connectivity-based approach, as lesion locations disrupting addiction map to a common brain circuit rather than a single region [21].

- Map Lesion Locations: Precisely map the anatomical locations of brain lesions from patients who experienced addiction remission onto a standard brain atlas.

- Compute Network Connectivity: Use a normative human connectome dataset (e.g., from 1,000 subjects) to calculate the functional connectivity network associated with each lesion location.

- Identify the Remission Network: Compare connectivity patterns of remission-associated lesions versus non-remission lesions. The resulting network shows positive connectivity to dorsal cingulate, lateral prefrontal cortex, and insula, and negative connectivity to medial prefrontal and temporal cortex [21].

Prevention: When designing neuromodulation trials, target hubs within this identified circuit (e.g., paracingulate gyrus, left frontal operculum) rather than a single anatomical structure.

Guide 2: Troubleshooting the Three-Stage Addiction Cycle Model in Preclinical Models

Problem: Difficulty in modeling the full, chronic-relapsing nature of human addiction in animal studies.

Solution: Deconstruct the addiction cycle into discrete, testable stages and employ behavioral paradigms specific to each [13] [6].

- Stage: Binge/Intoxication

- Core Dysfunction: Positive reinforcement and habit formation.

- Validated Protocol: Drug self-administration. Measure the escalation of intake with prolonged access to model the transition from controlled use to binge-like patterns [6].

- Stage: Withdrawal/Negative Affect

- Core Dysfunction: Reward deficits and stress surfeits.

- Validated Protocol: After chronic drug self-administration, impose abstinence and measure anxiety-like behaviors (e.g., elevated plus maze) and reward thresholds (e.g., intracranial self-stimulation) [6].

- Stage: Preoccupation/Anticipation (Craving)

- Core Dysfunction: Executive function deficits and craving.

- Validated Protocol: Cue-induced reinstatement of drug-seeking after extinction. This models relapse triggered by drug-associated cues [6].

Prevention: Use animal models that incorporate individual diversity, complex environments with alternative reinforcers, and the influence of stress to better model human vulnerability and resilience [13].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: What are the primary neurobiological circuits involved in addiction, and what are their core functions?

Addiction involves a dramatic dysregulation of three key motivational circuits [13] [6]:

- Basal Ganglia Circuit: Central to the

binge/intoxicationstage. It mediates the rewarding effects of drugs and the development of incentive salience and compulsive drug-seeking habits. - Extended Amygdala Circuit: Central to the

withdrawal/negative affectstage. It is responsible for the increases in negative emotional states (dysphoria, anxiety, irritability) and stress-like responses during drug withdrawal. - Prefrontal Cortex Circuit: Central to the

preoccupation/anticipationstage. It is involved in craving, deficits in executive function, and compromised inhibitory control, which contribute to relapse.

FAQ 2: How do neurotransmitter systems shift across the different stages of the addiction cycle?

The neurochemical landscape changes dramatically as an individual progresses through the addiction cycle. The table below summarizes key neurotransmitter alterations [13].

Table 1: Neurotransmitter Dynamics in the Addiction Cycle

| Stage | Neurotransmitter | Direction of Change |

|---|---|---|

| Binge/Intoxication | Dopamine | Increase [13] |

| Opioid Peptides | Increase [13] | |

| γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA) | Increase [13] | |

| Withdrawal/Negative Affect | Corticotropin-Releasing Factor (CRF) | Increase [13] |

| Dynorphin | Increase [13] | |

| Dopamine | Decrease [13] | |

| Endocannabinoids | Decrease [13] | |

| Preoccupation/Anticipation | Glutamate | Increase [13] |

| Hypocretin (Orexin) | Increase [13] | |

| Corticotropin-Releasing Factor (CRF) | Increase [13] |

FAQ 3: What is the key evidence for a shared neurocircuitry across different substance use disorders?

Human lesion studies provide causal evidence. Research shows that brain lesions resulting in remission of nicotine addiction are characterized by a specific pattern of functional connectivity. This same connectivity pattern is also associated with a reduced risk of alcoholism, suggesting a common network is disrupted [21]. This network involves positive connectivity to the dorsal cingulate, lateral prefrontal cortex, and insula, and negative connectivity to the medial prefrontal and temporal cortex [21].

FAQ 4: What are the main technical challenges in defining functional boundaries within addiction neurocircuitry?

- Spatial Overlap: The same brain structures (e.g., striatum, prefrontal cortex) are involved in multiple, distinct functions (reward, habit, executive control). Disentangling these roles is complex [13] [22].

- Temporal Dynamics: The neurocircuitry of addiction is not static. The dominant circuits and neuroadaptations shift from positive to negative reinforcement and from impulsive to compulsive behavior as the disorder progresses [13] [6].

- Individual Variability: Neurobiological factors underlying the transition from controlled use to addiction vary significantly between individuals, making it difficult to define a single "addicted brain" circuit map [13].

- Circuit Integration: These circuits do not operate in isolation. They form a complex, integrated network where dysfunction in one node can dysregulate the entire system, making it difficult to assign a specific behavior to a single region [22].

Experimental Protocols & Workflows

Protocol 1: Lesion Network Mapping to Identify Therapeutic Brain Targets

This methodology is used to identify brain circuits causally involved in addiction remission by analyzing lesions in patients who spontaneously recovered [21].

- Primary Materials: Database of patients with focal brain lesions and detailed behavioral history (e.g., smoking status); Normative human connectome dataset (e.g., from 1000 subjects); Standard brain atlas software.

- Step-by-Step Workflow:

- Patient Stratification: Identify two independent cohorts of patients who were daily smokers at the time of brain lesion. Stratify them into those who remitted (quit easily, no relapse, no craving) and those who did not.

- Lesion Mapping: Precisely trace each patient's lesion location and map it to a standard brain atlas (e.g., MNI space).

- Network Computation: For each lesion location, compute the functional connectivity pattern across the entire brain using the normative connectome data. This creates a "connectivity map" for every lesion.

- Statistical Comparison: Voxel-wise comparison of connectivity maps from the remission group versus the non-remission group to identify a common "addiction remission network."

- Validation: Test the generalizability of the identified network in an independent cohort (e.g., patients with alcohol addiction risk scores) and assess its specificity against other neuropsychological variables.

Protocol 2: Validating the Three-Stage Addiction Cycle in Rodent Models

This protocol outlines established methods for modeling the core stages of addiction in animals, allowing for the investigation of underlying neurocircuitry [13] [6].

- Primary Materials: Intravenous catheters for self-administration; Operant conditioning chambers; Microdialysis or fast-scan cyclic voltammetry equipment; Drugs of abuse (e.g., cocaine, heroin).

- Step-by-Step Workflow:

- Binge/Intoxication Stage:

- Procedure: Train rats to self-administer a drug (e.g., cocaine) by pressing a lever. Progress from short access (1-2 hours) to extended or intermittent long access (6+ hours) to promote escalation of intake.

- Measure: Number of infusions earned; breakpoint on a progressive ratio schedule.

- Withdrawal/Negative Affect Stage:

- Procedure: After stable escalation, impose a period of forced abstinence.

- Measure: Anxiety-like behaviors (e.g., time in open arms of an elevated plus maze); reward thresholds (intracranial self-stimulation); levels of stress neurotransmitters (e.g., CRF in the amygdala via microdialysis).

- Preoccupation/Anticipation (Craving) Stage:

- Procedure: After extinction of drug-seeking (lever presses no longer deliver drug), present previously drug-paired cues (e.g., light, tone).

- Measure: Number of non-reinforced lever presses during cue presentation (reinstatement of drug-seeking).

- Binge/Intoxication Stage:

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Research Materials for Addiction Neurocircuitry Analysis

| Item | Function & Application |

|---|---|

| Normative Human Connectome Dataset | A large-scale map of human brain connectivity used as a reference to compute the network effects of focal brain lesions or stimulation sites [21]. |

| Animal Models of Addiction | Preclinical models (typically rodent) that recapitulate specific stages of addiction (binge, withdrawal, relapse) for controlled investigation of neurocircuitry and neuropharmacology [13] [6]. |

| Functional Magnetic Resonance Imaging (fMRI) | Non-invasive neuroimaging technique used in humans to measure brain activity (via BOLD signal) in response to drug cues or during rest, allowing for functional connectivity analysis [21] [23]. |

| Drug Self-Administration Apparatus | Operant conditioning chambers used in animal research where subjects perform an action (e.g., lever press) to receive intravenous infusions of a drug, modeling drug-taking behavior [6]. |

| Lesion Network Mapping Software | Computational tools for mapping brain lesions to a standard atlas and calculating their connectivity profiles using the connectome, enabling the identification of symptom-specific brain circuits [21]. |

| Neuromodulation Techniques (TMS / DBS) | Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation (TMS) and Deep Brain Stimulation (DBS) are used to test the causal role of specific brain circuits by modulating their activity, with potential therapeutic applications [21]. |

Advanced Methodologies in Circuit Analysis: From Computational Models to Neuromodulation

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

General Framework Questions

Q1: What are the key differences between model-based and model-free reinforcement learning in the context of addiction research?

Model-based and model-free reinforcement learning represent two distinct computational approaches for understanding decision-making processes, which are often impaired in addiction.

Model-Free RL: This is a reflexive system where agents learn action values directly from experience without building an internal model of the environment. It associates actions with outcomes through trial and error, creating habitual behaviors. In addiction, this system becomes overactive, leading to compulsive drug-seeking behaviors even when outcomes are no longer desirable [24] [25].

Model-Based RL: This is a deliberative system where agents learn and utilize an internal model of the environment's dynamics to plan actions. It can simulate future states and outcomes before taking action. Addiction research suggests this system becomes compromised, reducing flexible, goal-directed behavior [24] [25].

The transition from model-based to model-free control represents a core computational mechanism in the development of compulsive habits in addiction [25].

Q2: How can Bayesian inference help address uncertainty in computational models of addiction neurocircuitry?

Bayesian inference provides a mathematical framework for updating beliefs (probability distributions) about model parameters as new data becomes available. This is particularly valuable in addiction research due to the high variability in patient responses and neural adaptations.

- Prior Distributions: Researchers can incorporate existing knowledge (e.g., from previous studies or theoretical constraints) as prior probabilities [26].

- Posterior Distributions: As new experimental data is collected (likelihood), Bayesian methods combine priors with data to form updated posterior distributions, which represent refined knowledge about neurocircuitry parameters [26].

- Quantifying Uncertainty: Unlike point estimates, posterior distributions naturally capture uncertainty, allowing researchers to make direct probability statements about parameters, such as the strength of a synaptic connection or the effect of a pharmacological intervention [26].

This approach is especially useful for modeling complex, multi-stage addiction processes and for integrating diverse data types within a single coherent framework [27].

Q3: What common computational challenges arise when fitting reinforcement learning models to human behavioral data in addiction studies?

Researchers often encounter several technical challenges when applying RL models to clinical populations:

- Parameter Identifiability: Different combinations of learning rates, discount factors, and inverse temperature parameters can produce identical choice patterns, making the true underlying mechanism difficult to discern.

- Model Misspecification: Standard RL models may not capture all relevant cognitive processes, such as attention or working memory deficits, which are often impaired in addiction.

- Exploration-Exploitation Dilemma: Addicted individuals often exhibit altered exploration strategies, which standard epsilon-greedy or softmax policies may not fully capture [24].

- Credit Assignment: Determining which actions led to rewarding or aversive outcomes is particularly challenging in complex environments with delayed consequences, a deficit that may be central to addiction [25].

Technical Implementation Questions

Q4: How do I choose an appropriate exploration strategy for my reinforcement learning agent in a novel behavioral task?

The choice of exploration strategy depends on your action space and research question:

- Discrete Action Spaces: Epsilon-greedy strategies are commonly used, where the agent selects a random action with probability ε (exploration) and the best-known action otherwise (exploitation). The ε parameter is typically high initially and decays over time [24].

- Continuous Action Spaces: Adding random noise to actions or using entropy regularization in the loss function encourages exploration by making the policy less certain about its choices [24].

- Advanced Methods: For more sophisticated exploration, intrinsic motivation methods like "curiosity" drive exploration by rewarding the agent for visiting novel states or for taking actions where outcomes are hard to predict [24].

Q5: What are the essential steps for implementing Markov Chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) methods for Bayesian model estimation?

Proper implementation of MCMC requires careful attention to several steps:

Algorithm Selection: Choose an appropriate sampling algorithm based on your model structure:

- Metropolis-Hastings: General-purpose algorithm applicable to many problems

- Gibbs Sampling: Efficient when conditional distributions are known and easy to sample from

- Hamiltonian Monte Carlo (HMC) & NUTS: More advanced algorithms that better explore complex, high-dimensional parameter spaces [26]

Convergence Diagnostics: Always assess whether your chains have properly converged to the target posterior distribution using:

- Trace Plots: Visual inspection should show stable fluctuation around a mean value ("fat hairy caterpillar" appearance)

- Gelman-Rubin Statistic (R-hat): Values should be close to 1 (typically <1.1) to indicate convergence

- Effective Sample Size (ESS): Should be sufficiently large to ensure reliable estimates [26]

Model Checking: Validate your model using posterior predictive checks to ensure it can generate data similar to your actual observations [26].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: RL Agent Fails to Learn Optimal Policy

| Symptoms | Potential Causes | Solutions | Related Addiction Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Agent consistently chooses suboptimal actions | Poor balance between exploration and exploitation | Systematically decay exploration rate (ε); implement intrinsic curiosity rewards [24] | Models addictive behavior where exploration of alternatives diminishes |

| Unstable learning curves | Learning rate too high | Reduce learning rate; implement adaptive learning rate schedules | Analogous to maladaptive learning in addiction with heightened reward sensitivity |

| Agent fails to generalize | Incorrect state representation | Include task-relevant features in state space; consider feature engineering | Reflects impaired state representation in addiction neurocircuitry |

| Q-values diverge to infinity | Insufficient regularization | Apply gradient clipping; implement reward scaling | Models compulsive behavior where value representations become pathological |

Problem: Bayesian Model Estimation Issues

| Symptoms | Potential Causes | Solutions | Diagnostic Tools |

|---|---|---|---|

| MCMC chains fail to converge | Poor initialization; model misspecification | Run multiple chains from different starting points; simplify model structure | Gelman-Rubin statistic (R-hat >> 1.1) [26] |

| High autocorrelation in samples | Inefficient sampling algorithm | Switch to HMC/NUTS; reparameterize model | Effective Sample Size (ESS) diagnostic [26] |

| Poor model fit to data | Inappropriate likelihood function | Conduct posterior predictive checks; compare alternative models | Posterior predictive p-values [26] |

| Computational bottlenecks | High-dimensional parameter space | Implement variational inference approximations; use more efficient software (e.g., Stan) [26] | Memory usage and iteration time |

Problem: Translating Computational Models to Addiction Phenomena

| Challenge | Technical Issue | Potential Solutions | Theoretical Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Modeling transition from goal-directed to habitual behavior | Determining relative contribution of model-based vs. model-free systems | Use two-step task designs with computational modeling to decompose contributions [25] | Addiction may involve a shift from model-based to model-free control dominance [25] |

| Capturing compulsive drug-seeking despite negative consequences | Standard RL agents avoid negative states | Implement asymmetric learning for positive vs. negative outcomes; alter baseline reward expectations [27] | Proposed models include raised reward thresholds in addiction [27] |

| Modeling craving and relapse | Standard RL frameworks poorly capture internal states | Incorporate interoceptive states into state representation; use active inference frameworks [25] | Craving may stem from incorrect beliefs about physiological states [25] |

Experimental Protocols & Methodologies

Protocol 1: Two-Step Task for Decomposing Model-Based and Model-Free Control

This behavioral task is widely used to quantify the relative contributions of model-based and model-free decision systems, which are often imbalanced in addiction [25].

Workflow Diagram: Two-Step Task Computational Analysis

Step-by-Step Methodology:

Task Structure: Participants make two sequential choices. The first choice leads to one of two second-stage states with probabilistic transitions (typically 70% common, 30% rare transitions).

Data Collection: Record choices and reaction times at both decision stages across multiple trials (typically 200-300 trials).

Computational Modeling: Fit hybrid RL models that include both model-based and model-free components:

- Model-Free Component: Updates action values based on reinforcement history using temporal difference learning

- Model-Based Component: Uses knowledge of the task structure (transition probabilities) to plan actions

Parameter Estimation: Estimate individual subject parameters using maximum likelihood or hierarchical Bayesian methods, focusing on:

- Learning rates for each system

- Relative weighting of model-based vs. model-free control

- Decision noise parameters

Clinical Correlation: Relate individual differences in computational parameters to addiction severity, craving measures, or neural activity [25].

Protocol 2: Hierarchical Bayesian Modeling of Addiction Longitudinal Data

This protocol describes how to implement Bayesian methods for analyzing longitudinal clinical data in addiction research, which often features multiple levels of variability (within-subject, between-subject, across time).

Workflow Diagram: Hierarchical Bayesian Modeling

Step-by-Step Methodology:

Model Specification:

- Define the hierarchical structure: individual-level parameters drawn from group-level distributions

- Specify appropriate likelihood functions for your data type (e.g., Bernoulli for binary outcomes, Gaussian for continuous)

- Choose weakly informative priors that regularize estimates without dominating the data

Computational Implementation:

- Code model in probabilistic programming languages like Stan, PyMC, or JAGS

- Implement appropriate MCMC sampling (NUTS is recommended for complex models)

- Run multiple chains from dispersed initial values

Convergence Diagnostics:

- Check R-hat statistics (<1.1 indicates convergence)

- Examine trace plots for good mixing

- Calculate effective sample size to ensure sufficient independent samples

Model Validation:

- Perform posterior predictive checks to assess model fit

- Compare with alternative models using information criteria (LOO, WAIC)

- Conduct sensitivity analyses to check prior influence

Result Interpretation:

- Report posterior means and credible intervals for key parameters

- Visualize posterior distributions to communicate uncertainty

- Make probabilistic statements about hypotheses (e.g., "There is 92% probability that the treatment reduces craving") [26]

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Computational Frameworks & Software

| Tool Name | Type | Primary Function | Application in Addiction Research |

|---|---|---|---|

| Stan | Probabilistic Programming | Bayesian inference using HMC/NUTS sampling | Hierarchical modeling of clinical trial data; dose-response modeling [26] |

| Python RLlib | Reinforcement Learning Library | Scalable RL implementation for various algorithms | Modeling decision-making processes at computational level [24] |

| MATLAB Computational Psychiatry Pack | Model Fitting Toolkit | Maximum likelihood and Bayesian estimation of cognitive models | Fitting RL models to behavioral data from addicted individuals |

| JAGS | Bayesian Analysis Tool | Gibbs sampling for Bayesian models | Alternative to Stan for models where conditional distributions are tractable [26] |

| AI Gym | RL Environment | Standardized environments for testing RL agents | Developing and validating novel RL models of addictive behavior |

Conceptual Frameworks for Addiction Modeling

| Framework | Key Components | Addiction Application | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Model-Based vs Model-Free RL | Dual-system architecture of decision-making | Transition from goal-directed to habitual drug use [25] | [24] [25] |

| Active Inference | Bayesian belief updating with precision weighting | Compulsive drug seeking as faulty belief updating [25] | [25] |

| Reinforcement Learning Theory of Addiction | Temporal difference learning with dopamine | Drug-induced hijacking of natural reward learning [27] | [27] |

| Bayesian Brain Hypothesis | Predictive coding and precision estimation | Aberrant salience attribution in addiction [25] | [25] |

Quantitative Data Reference Tables

Table 1: Typical Parameter Ranges in RL Models of Addiction

| Parameter | Healthy Controls | Addicted Individuals | Computational Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Model-Based Weight | 0.5-0.8 | 0.2-0.5 | Reduced goal-directed control in addiction [25] |

| Learning Rate (Reward) | 0.2-0.4 | 0.3-0.6 | Heightened sensitivity to drug rewards [27] |

| Learning Rate (Punishment) | 0.3-0.5 | 0.1-0.3 | Reduced sensitivity to negative outcomes [27] |

| Inverse Temperature | 3-10 | 5-15 | Increased choice rigidity in addiction |

| Discount Factor (γ) | 0.8-0.95 | 0.5-0.8 | More steeply discounted future rewards [27] |

Table 2: Bayesian Model Comparison Metrics

| Metric | Formula | Interpretation | Advantages |

|---|---|---|---|

| Watanabe-Akaike Information Criterion (WAIC) | -2(log pointwise predictive density - effective number of parameters) | Lower values indicate better predictive accuracy | Fully Bayesian; works for singular models |

| Leave-One-Out Cross Validation (LOO) | Σ log p(yi|y{-i}) | Out-of-sample prediction accuracy | More robust than WAIC for influential observations |

| Bayes Factor | p(D|M1)/p(D|M2) | Relative evidence for one model over another | Direct Bayesian model comparison |

| Postior Model Probability | p(M|D) ∝ p(D|M)p(M) | Absolute probability of a model given data | Requires specifying prior model probabilities |

Troubleshooting Guides

Resting-State fMRI (rs-fMRI) Preprocessing and Analysis

Q1: How do I address common artifacts in rs-fMRI data, such as head motion and physiological noise? Excessive head motion and physiological noise (e.g., from cardiac and respiratory cycles) are major confounds in rs-fMRI, as they can mimic or obscure genuine neural signals in functional connectivity analysis [28].

- Head Motion: Implement rigorous motion correction during preprocessing. Scrub volumes with framewise displacement exceeding 0.2-0.5 mm. Include motion parameters as regressors in your general linear model.

- Physiological Noise: Use data-driven methods like ICA to identify and remove noise components related to physiological processes. If possible, record cardiac and respiratory rhythms during the scan and use them for retrospective correction.

- Low-Frequency Drift: Apply a high-pass filter (typically with a cutoff around 0.008-0.01 Hz) to remove slow scanner drifts that can dominate the BOLD signal.

Q2: What steps should I take if my functional connectivity matrices show poor test-retest reliability? Poor reliability can stem from insufficient data quality or suboptimal analytical choices [28].

- Increase Scan Duration: The reliability of functional connectivity estimates increases with scan length. Aim for at least 10-15 minutes of resting-state data.

- Ensure Sufficient Preprocessing: Verify that all standard preprocessing steps (motion correction, normalization, smoothing, band-pass filtering, and nuisance regression) have been correctly applied.

- Check Network Definitions: The reliability of connectivity matrices depends on the accurate definition of nodes (brain regions) and edges (connections). Use standardized, well-validated brain atlases for parcellation.

Effective Connectivity and Spectral DCM

Q3: How do I resolve model convergence issues or poor parameter identifiability in Spectral DCM? Spectral DCM infers effective connectivity by fitting a model to the cross-spectral density of the data [29]. Convergence issues often relate to model specification.

- Simplify the Model: Begin with a smaller network of brain regions (3-4 nodes). Large, overly complex models with many free parameters can be poorly identified and fail to converge.

- Check Priors: DCM uses Bayesian estimation with prior distributions on parameters. Ensure you are using appropriate priors. Very tight priors can prevent the model from fitting the data, while overly wide priors can lead to instability.

- Inspect Data Quality: As with all fMRI analyses, ensure your input time series are of high quality, with minimal artifacts. Noisy data can prevent the algorithm from finding a clear optimum.

Q4: What does it mean if a change in effective connectivity does not correlate with a change in functional connectivity? This is an expected scenario, not necessarily an error. Effective connectivity represents the directed, causal influence one neural region exerts over another, measured in Hz (rate of change) [29]. Functional connectivity is a measure of undirected, statistical dependence (e.g., correlation) between regions [30]. A single change in a directed effective connection can redistribute activity across the entire network, leading to complex changes in all pairwise correlations. Therefore, the brain region pairs showing the largest changes in functional connectivity may not be the same as those with the largest changes in effective connectivity [29].

General Technical Challenges

Q5: How can I programmatically generate reproducible and high-quality visualizations of my connectivity results? Relying on manual adjustments in GUI-based tools hinders replication and scalability [31].

- Adopt Code-Based Tools: Use well-documented software packages within programming environments like R (

cowplot,ggseg), Python (Matplotlib,Nilearn), or MATLAB. These allow you to generate publication-ready figures directly from code. - Leverage Templates: Utilize online resources and code-sharing platforms to find templates for brain connectivity visualizations, such as heat maps and connectomes.

- Enable Batch Processing: Code-based visualization allows you to easily iterate over multiple subjects or conditions, which is essential for quality control in large datasets [31].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q: What is the fundamental difference between functional and effective connectivity? A: Functional connectivity is a statistical description of "what" brain regions are synchronized. It quantifies temporal correlations or dependencies (e.g., using Pearson correlation) but does not imply direction or causality. Effective connectivity describes "how" and in "which direction" regions influence each other, modeling the causal impact one neural system exerts over another [30]. In essence, functional connectivity is a correlation, while effective connectivity is a causal estimate [29].

Q: When should I choose Spectral DCM over other effective connectivity methods like Granger Causality or Structural Equation Modeling? A: The choice depends on your data and research question. Spectral DCM is ideal for resting-state fMRI where there are no controlled experimental inputs, as it models endogenous neural fluctuations [29]. It is a state-space model that distinguishes between hidden neural states and observed BOLD signals. Granger Causality is a non-parametric method often applied to electrophysiological data like EEG with high temporal resolution [30]. Structural Equation Modeling (SEM) requires a pre-specified anatomical model to test the strength of connections between regions but is less flexible for exploring novel network dynamics [32].

Q: Can these neuroimaging techniques inform addiction treatment development? A: Yes. By mapping the neurocircuitry of addiction, these techniques can identify specific network dysfunctions as biomarkers and treatment targets. For example, addiction involves a three-stage cycle (binge/intoxication, withdrawal/negative affect, preoccupation/anticipation) mediated by dysregulation in specific circuits like the basal ganglia, extended amygdala, and prefrontal cortex [13]. Effective connectivity analysis with Spectral DCM could pinpoint the precise directional dysfunction within this circuit (e.g., weakened prefrontal control over the striatum), which can then be targeted with neuromodulation therapies or tracked as a biomarker of treatment response.

Q: What are the key limitations of fMRI for measuring neural activity? A: fMRI has two primary limitations [28] [33]:

- Indirect Measurement: fMRI measures the Blood-Oxygen-Level-Dependent (BOLD) signal, which is a hemodynamic response correlated with neural activity, not the electrical activity of neurons themselves.

- Temporal Resolution: The BOLD response is slow, unfolding over 1-5 seconds, which is much slower than the millisecond-scale dynamics of neural firing.

Data Presentation

Comparison of Neuroimaging Modalities

Table 1: Key characteristics of functional neuroimaging techniques relevant to connectivity analysis.

| Technique | Spatial Resolution | Temporal Resolution | Primary Use in Connectivity | Key Advantage |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| fMRI | Medium-High | Low (seconds) | Functional & Effective Connectivity | Whole-brain coverage; non-invasive; no radiation [33]. |

| EEG/QEEG | Low | Very High (milliseconds) | Functional Connectivity | Directly measures neural electrical activity; excellent for fast dynamics [30]. |

| MEG | Medium | Very High (milliseconds) | Functional & Effective Connectivity | Combines good spatial localization with high temporal resolution [30]. |

| SPECT | Medium | Very Low (minutes) | Functional Connectivity (broad) | Provides a broader overview of brain function over time [33]. |

Key Metrics for Connectivity Analysis

Table 2: Common metrics and their interpretations in functional and effective connectivity studies.

| Metric | Connectivity Type | Interpretation | Typical Use Case |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pearson Correlation | Functional | Linear, undirected statistical dependence between two time series. | Identifying nodes within a resting-state network (e.g., Default Mode Network) [28]. |

| Dynamic Causal Modeling (DCM) | Effective | A Bayesian framework to infer the directed influence between regions and how it is modulated by experimental conditions. | Testing how a cognitive task or drug challenge alters causal pathways in a pre-defined network [29]. |

| Granger Causality | Effective | A time-series-based measure where if past values of signal X improve the prediction of signal Y, then X "Granger-causes" Y. | Analyzing directed influences in high-temporal-resolution data like EEG [30]. |

| Structural Equation Modeling (SEM) | Effective | Tests the causal strength of connections within a pre-specified anatomical model. | Testing hypotheses about network interactions based on known neuroanatomy [32]. |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Conducting a Resting-State fMRI Experiment

Aim: To acquire data for estimating whole-brain functional connectivity networks at rest.

- Participant Preparation: Screen for MRI contraindications. Instruct the participant to lie still with their eyes open, fixating on a cross-hair, and to let their mind wander without falling asleep.

- Data Acquisition: Use a standard EPI sequence on a 3T MRI scanner. Acquisition parameters: TR = 2000 ms, TE = 30 ms, voxel size = 3x3x3 mm³, whole-brain coverage, ~10-15 minutes duration (300-450 volumes).

- Preprocessing Pipeline:

- Slice Timing Correction: Correct for acquisition time differences between slices.

- Realignment: Correct for head motion using a rigid-body transformation.

- Coregistration: Align the functional images to the participant's high-resolution T1-weighted anatomical scan.

- Normalization: Warp the images to a standard stereotaxic space (e.g., MNI).

- Spatial Smoothing: Apply a Gaussian kernel (e.g., 6-8 mm FWHM) to increase signal-to-noise ratio.

- Nuisance Regression: Regress out signals from white matter, cerebrospinal fluid, and the global signal, along with the 24 motion parameters.

- Band-Pass Filtering: Apply a filter (e.g., 0.008-0.09 Hz) to retain low-frequency fluctuations of interest.

Protocol 2: Applying Spectral DCM to rs-fMRI Data

Aim: To estimate the directed effective connectivity within a defined brain network during rest [29].

- Region of Interest (ROI) Selection:

- Based on your hypothesis (e.g., a reward network in addiction), select key ROIs (e.g., Ventral Striatum, Prefrontal Cortex, Amygdala).

- Extract the principal eigenvariate of the BOLD time series from each ROI.

- Model Specification:

- Define a model architecture (the "A" matrix) that specifies which regions are allowed to be connected.

- Set Bayesian priors on the strength and variance of these connections.

- Model Estimation:

- Use the spectral DCM algorithm (e.g., as implemented in SPM12) to fit the model. The algorithm optimizes the effective connectivity parameters to best explain the observed cross-spectral density of the ROI time series.

- Model Comparison & Inference:

- If you have multiple competing model architectures, use Bayesian model selection to identify the model that best explains the data.

- For the winning model, inspect the posterior parameter estimates to determine the strength and direction (excitatory/inhibitory) of the effective connections.

Signaling Pathways and Workflows

Diagram 1: Spectral DCM estimation from BOLD signal.

Diagram 2: Simplified addiction neurocircuitry model.

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 3: Essential research reagents and computational tools for connectivity analysis.

| Item / Tool | Function / Purpose | Example / Note |

|---|---|---|

| fMRI Scanner | Acquires the BOLD signal by measuring changes in blood oxygenation related to neural activity. | Typically a 3T or 7T MRI scanner with appropriate head coils [28]. |

| Standardized Brain Atlas | Provides a parcelation of the brain into distinct regions for defining network nodes. | Automated Anatomical Labeling (AAL), Harvard-Oxford Atlas. |

| Preprocessing Software | Corrects for artifacts and standardizes data before analysis. | FSL, SPM, AFNI, fMRIPrep. |

| Spectral DCM Toolbox | Software implementation for performing Spectral DCM analysis. | Available within the SPM12 software package [29]. |

| Programmatic Visualization Library | Generates reproducible, high-quality figures of brain networks and connectivity matrices. | Nilearn (Python), ggseg (R), BrainNet Viewer (MATLAB) [31]. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) and Troubleshooting

This section addresses common technical and methodological questions researchers encounter when applying neuromodulation techniques to study addiction neurocircuitry.

Q1: What are the most effective cortical targets and parameters for reducing drug craving in substance use disorders (SUDs)?

A1: Targeting the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (DLPFC) is most supported by evidence. A 2024 systematic review and meta-analysis found that repetitive Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation (rTMS) applied to the left DLPFC produced medium to large effect sizes in reducing substance use and craving [34]. For Transcranial Direct Current Stimulation (tDCS), protocols often use anodal stimulation of the right DLPFC (to enhance inhibitory control) or cathodal stimulation of the left DLPFC (to reduce reward-based motivation), also yielding medium effect sizes, though results are more variable [34]. The efficacy is significantly higher when multiple stimulation sessions are applied rather than single sessions [34].

Q2: A subject in our Deep TMS study experienced a seizure. What are the immediate steps and how should the incident be investigated?

A2: Although rare, seizures can occur. Immediate steps include [35]:

- Cease stimulation immediately.

- Ensure medical safety; manage the seizure following standard medical protocols (e.g., protecting from injury).

- Transport to emergency services if necessary.

- Report the event to your Institutional Review Board (IRB) and the device manufacturer.

A thorough investigation should review:

- Subject eligibility: Screen for pre-existing neurological conditions, brain injury, or history of seizures [35] [36].

- Concomitant medications: Review medications, particularly those known to lower the seizure threshold (e.g., high doses of antidepressants) [35].

- Substance use: Assess recent alcohol or drug consumption, as high alcohol intake the night before treatment has been linked to seizure occurrence during TMS [35].

- Device parameters: Verify that stimulation intensity and pattern were within recommended safety guidelines [36].

Q3: Our DBS system for addiction research is yielding suboptimal symptom relief. What is a systematic approach to troubleshooting?

A3: Suboptimal outcomes in DBS can arise from multiple factors. A systematic troubleshooting clinic model, as developed by the University of Florida, involves a comprehensive, multi-disciplinary evaluation [37]:

- Clinical Re-evaluation: Re-assess the patient's current status, including standardized rating scales in different medication and stimulation states. This can take 1-2 hours [37].

- Lead Placement Verification: Import post-operative MRI or CT imaging into a 3-D brain atlas to verify the location of the DBS lead. A misplaced or sub-optimally placed lead is a common cause of failure [37].

- Programming Optimization: Systematically test the thresholds for clinical benefit and side effects on every contact of the DBS lead. Based on this mapping, attempt to reprogram the patient with new parameters [37].

- Medication Adjustment: Review and adjust concomitant medications, as the interaction between stimulation and medication is critical [37].

- Surgical Re-evaluation: If the lead is confirmed to be misplaced and reprogramming is ineffective, surgical repositioning may be considered [37].

Q4: What are the critical safety contraindications for Deep TMS and TBS studies?

A4: The primary safety concern involves the interaction of the magnetic field with metal or implanted electronic devices [35] [36].