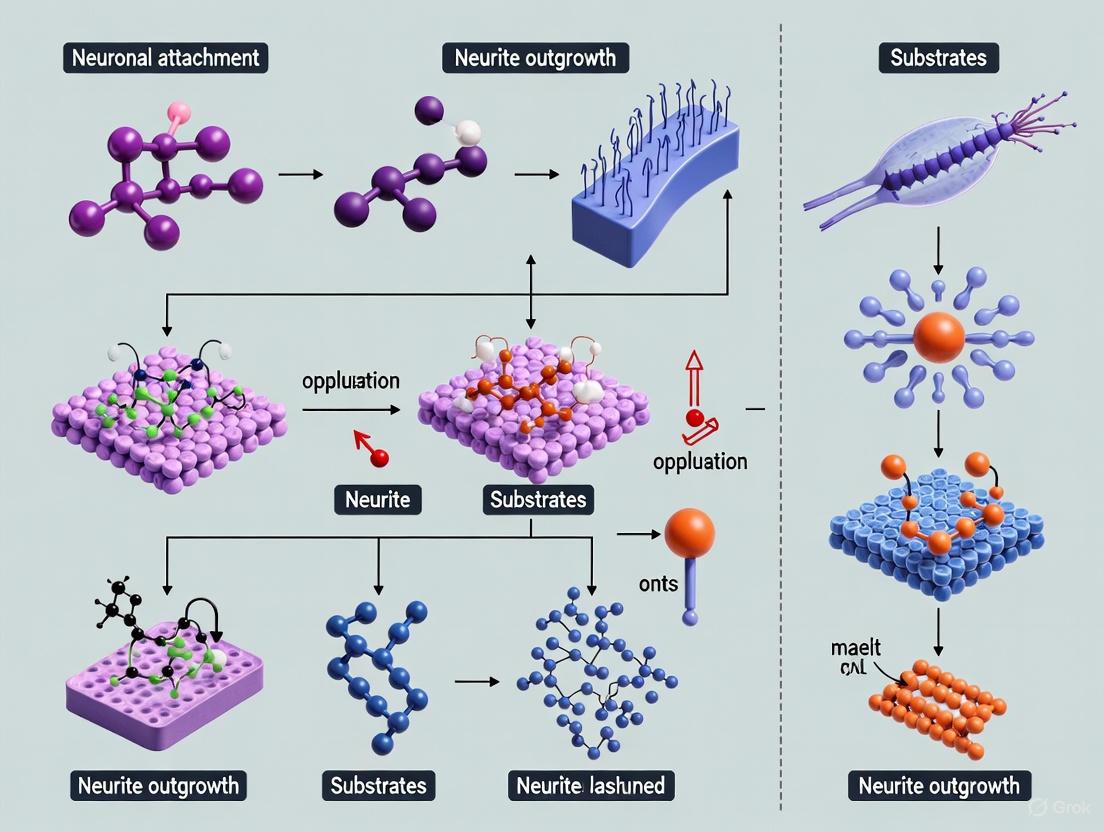

Strategic Enhancement of Neuronal Attachment and Neurite Outgrowth for Advanced Biomedical Applications

This article provides a comprehensive resource for researchers and drug development professionals seeking to optimize in vitro neuronal models.

Strategic Enhancement of Neuronal Attachment and Neurite Outgrowth for Advanced Biomedical Applications

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive resource for researchers and drug development professionals seeking to optimize in vitro neuronal models. It covers the foundational principles of neuron-substrate interactions, detailing established and emerging methodologies for promoting attachment and outgrowth. The content further explores advanced troubleshooting, optimization strategies, including dynamic platforms and glial co-culture, and concludes with rigorous validation and comparative analysis techniques to ensure reliable, quantifiable outcomes for both basic research and high-throughput screening applications.

The Blueprint for Growth: Core Principles of Neuron-Substrate Interactions

Technical Troubleshooting Guide: FAQs for Neuronal Cell Culture

This guide addresses common challenges in experimental workflows aimed at improving neuronal attachment and neurite outgrowth on engineered substrates.

FAQ 1: My neuronal cells are not adhering properly to my RGD-functionalized substrate. What could be wrong?

- Potential Cause: The RGD motif may be presented in a suboptimal conformation or density, or it may be competing with adsorbed serum proteins.

- Troubleshooting Steps:

- Check Peptide Conformation: The linear RGD peptide has significantly lower affinity (100-1000 fold) for integrins compared to the native RGD loop in fibronectin. Consider using a cyclic RGD variant or engineering the motif within a cysteine-constrained loop (e.g., CTGRGDSPAC, or "FNCC") to mimic the natural β-hairpin turn found in fibronectin, which dramatically enhances cell attachment and spreading [1].

- Evaluate Substrate Fouling: If your biomaterial is highly adsorptive, it will rapidly coat itself with serum proteins (e.g., fibronectin, vitronectin) from your culture media. This creates a complex background that can overshadow your synthetic RGD peptide. In some cases, high densities of synthetic RGD can even compete with and inhibit the robust signaling from adsorbed native proteins. Test cell adhesion in reduced-serum conditions or use non-fouling materials (e.g., certain PEG hydrogels) to ensure your RGD motif is the dominant adhesive signal [2].

- Verify Integrin Expression: Ensure your neuronal cell type expresses RGD-sensitive integrins, such as αvβ3 or α5β1. If not, alternative motifs may be required.

FAQ 2: I have good cell adhesion, but neurite outgrowth is poor. How can I promote outgrowth specifically?

- Potential Cause: Adhesion is necessary but not sufficient for neurite outgrowth. The substrate may lack specific outgrowth-promoting motifs or present inhibitory cues.

- Troubleshooting Steps:

- Incorporate Specific Outgrowth Motifs: Neurite outgrowth is driven by specific sequences beyond the standard RGD.

- The VFDNFVLK peptide from the fnD domain of tenascin-C is a potent promoter of neurite extension and can even overcome inhibition from chondroitin sulfate proteoglycans [3].

- For α4β1 integrin-mediated outgrowth, ensure your fibronectin substrate includes the IIICS/V region containing the LDV motif. The interaction between this domain and α4β1 is a strong promoter of neurite outgrowth, and it requires the adaptor protein paxillin for signaling [4].

- Use a Combination of Proteins: Laminin is consistently one of the most effective matrices for neurite outgrowth. Consider coating with laminin alone or in combination with other proteins. Studies show neurite growth is more pronounced on laminin than on fibronectin or collagen [5].

- Check the Status of Your Fibronectin: Native, intact plasma fibronectin may not support adhesion or outgrowth for all neuronal types. Denaturation can sometimes uncover cryptic RGD sites, enhancing its functionality [6].

- Incorporate Specific Outgrowth Motifs: Neurite outgrowth is driven by specific sequences beyond the standard RGD.

FAQ 3: My in vitro results with RGD peptides are promising, but they fail in animal models. Why?

- Potential Cause: The in vivo environment is far more complex, with rapid protein adsorption and different integrin signaling dynamics.

- Troubleshooting Steps:

- Pre-adsorb with Serum Proteins: Perform a pre-test by exposing your RGD-functionalized implant to serum or placing it in vivo for a short period (e.g., 30 minutes), then retrieving it and evaluating cell adhesion in vitro. This can reveal if protein adsorption is interfering with your peptide's function [2].

- Consider Alternative Motifs: For certain applications, non-RGD peptides may be more effective. For example, the DGEA peptide (derived from collagen I) was shown to enhance osteoblastic differentiation where RGD was inhibitory in a bone formation model [2].

- Optimize Peptide Density: A high density of RGD peptides can sometimes lead to excessive adhesion, reducing cell motility and process extension. Titrate the concentration of RGD on your surface to find an optimal range for neurite outgrowth.

The following tables summarize key experimental findings from the literature to guide your experimental design.

Table 1: Neurite Outgrowth Performance of Different ECM Molecules

| ECM Molecule / Peptide | Key Motif(s) | Relative Neurite Outgrowth | Key Integrins Involved | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Laminin-1 | SIKVAV (and others) | +++ (Most pronounced) [5] | α1β1, α3β1, α6β1, α7β1 [4] | A classic and highly effective promoter of neurite outgrowth. |

| Fibronectin (V120 region) | RGD + IIICS/V (LDV) | ++ (Enhanced) [4] | α4β1, α5β1 [4] | Outgrowth is highly dependent on α4β1-paxillin interaction. |

| Tenascin-C (fnD domain) | VFDNFVLK | +++ (Dramatically increased) [3] | To be determined | Potent outgrowth promotion; can overcome inhibitory cues. |

| Collagen I | DGEA | + | α1β1, α2β1 [4] | Supports baseline outgrowth. |

| RGD peptide (linear) | RGD | + to ++ (Variable) [2] | αvβ3, α5β1, others | Effectiveness highly dependent on presentation and context. |

Table 2: Functional Comparison of RGD Presentations

| RGD Format | Example | Cell Adhesion | Neurite Outgrowth | Key Findings & Mechanisms |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Linear Peptide | GRGDSP | + | + | Low affinity; susceptible to competition; signaling is weaker than full-length proteins [2]. |

| Cysteine-Constrained Loop (FNCC) | CTGRGDSPAC | +++ | ++ | Mimics native fibronectin loop; enhances α5β1 integrin binding, cell spreading, and focal adhesion formation [1]. |

| In Native Fibronectin | RGD in FN-III10 | ++ | ++ | Requires synergy site (PHSRN in FN-III9); essential for embryonic development [7]. |

| In Denatured Fibronectin | N/A | +++ | Not specified | Denaturation uncovers cryptic RGD sites, dramatically enhancing adhesion compared to native FN [6]. |

Experimental Protocols for Key Assays

Protocol 1: Evaluating the Role of α4 Integrin-Paxillin Interaction in Neurite Outgrowth

This protocol is adapted from research demonstrating the critical role of the α4-paxillin interaction in neurite outgrowth on embryonic fibronectin substrates [4].

- 1. Cell Preparation:

- Use PC12 cells (a model for PNS neurons) that do not natively express α4 integrin.

- Transfect cells with constructs expressing:

- Wild-type α4 integrin.

- Mutant α4 integrin (e.g., E983A/Y991A) that cannot bind paxillin.

- Empty vector control.

- 2. Substrate Coating:

- Coat culture surfaces with recombinant fibronectin fragments containing the V120 region (which includes the IIICS/V domain with the α4β1-binding site).

- Use laminin or collagen-coated surfaces as controls for α4-independent outgrowth.

- 3. Neurite Outgrowth Assay:

- Plate transfected PC12 cells on the coated surfaces.

- Culture for 24-48 hours in serum-free medium supplemented with 50 ng/mL NGF to induce neuronal differentiation.

- Fix and stain cells for β-tubulin III (to visualize neurons and neurites).

- 4. Data Analysis:

- Quantify neurite outgrowth by measuring the length of the longest neurite per cell or the percentage of cells with neurites longer than the cell body diameter.

- Expected Outcome: Cells expressing wild-type α4 will show significantly enhanced neurite outgrowth on FN V120 compared to controls. Cells expressing the paxillin-binding-deficient α4 mutant will show outgrowth levels similar to the negative control, confirming the importance of this specific interaction.

Protocol 2: Testing the Efficacy of a Tenascin-Derived Peptide against Inhibitory Substrates

This protocol uses the VFDNFVLK peptide to overcome inhibition, such as that from the glial scar component CSPG [3].

- 1. Substrate Preparation:

- Coat glass coverslips with a mixture of inhibitory chondroitin sulfate proteoglycans (CSPGs).

- Co-add or pre-coat with the synthetic VFDNFVLK peptide. Use laminin-1 as a positive control and CSPGs alone as a negative control.

- 2. Cell Plating and Culture:

- Dissociate and plate primary dorsal root ganglion (DRG) neurons or other relevant neuronal cells onto the prepared substrates.

- Culture cells in a defined neuronal medium for 24-72 hours.

- 3. Analysis:

- Fix and immunostain for neuronal markers (e.g., β-tubulin III) and actin (phaloidin) to visualize cell morphology.

- Quantify total neurite length per neuron or the number of neurite crossings over a defined area.

- Expected Outcome: Neurons on CSPGs + VFDNFVLK will exhibit significantly longer and more extensive neurites compared to those on CSPGs alone, demonstrating the peptide's ability to promote outgrowth in an inhibitory environment.

Signaling Pathway and Experimental Workflow Diagrams

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents for Neuronal Substrate Research

| Reagent | Function/Application | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Recombinant Spider Silk (4RepCT) | A versatile, biocompatible biomaterial that can be genetically engineered to present specific adhesion motifs like RGD or FNCC [1]. | Allows for controlled presentation of peptides. Less adsorptive than some materials, reducing confounding protein adsorption. |

| Synthetic Peptide VFDNFVLK | A potent neurite outgrowth-promoting peptide derived from the fnD domain of tenascin-C [3]. | Can be used to coat surfaces or incorporate into hydrogels. Particularly useful for overcoming inhibitory environments like those containing CSPGs. |

| Recombinant Fibronectin Fragments (e.g., V120) | Contains the IIICS/V region that binds α4β1 integrin, crucial for studying α4-mediated neurite outgrowth [4]. | Essential for experiments focusing on the α4β1-paxillin signaling axis. |

| Paxillin Mutants (e.g., ΔLD4) | Used to dissect the role of paxillin domains in integrin signaling. The LD4 domain is critical for promoting neurite outgrowth [4]. | Transfection of dominant-negative mutants can pinpoint specific protein functions in neuronal signaling. |

| Hydroxyapatite (HA) Biomaterials | A highly adsorptive biomaterial used to study the effects of protein adsorption on synthetic peptide performance [2]. | Useful for modeling the complex in vivo environment where competition with serum proteins occurs. |

| Poly(Ethylene Glycol) (PEG) Hydrogels | A synthetic, non-fouling polymer that resists protein adsorption. Ideal as a "blank slate" for functionalization with specific peptides [8]. | Provides high control over the cellular microenvironment by eliminating confounding signals from adsorbed proteins. |

Core Concepts and Definitions

What are the fundamental mechanisms of topographical guidance? Topographical guidance, or contact guidance, is the phenomenon where cells sense and align with physical features on a substrate. The growth cone, a highly motile structure at the tip of a growing axon, translates these physical cues into localized cytoskeletal remodeling, directing axon outgrowth and turning [9] [10]. This process is driven by the dynamic reorganization of actin filaments and microtubules within the cell [10].

What is the role of immobilized chemical ligands? Immobilized chemical ligands are bio-active molecules (e.g., proteins like laminin or peptides like RGD) covalently bound or adsorbed to a substrate. They primarily influence neuronal attachment and neurite outgrowth by engaging specific cell surface receptors, such as integrins. This engagement triggers intracellular signaling pathways that promote cell adhesion, survival, and cytoskeletal reorganization [9].

How do these cues differ in their mode of action? The primary distinction lies in how the signal is presented and sensed:

- Physical/Topographical Cues: Provide a continuous, structural scaffold. Cells respond to the shape and geometry of the environment through mechanotransduction [10].

- Chemical/Ligand Cues: Provide discrete, molecular signals. Cells respond through specific receptor-ligand binding and biochemical signaling cascades [9].

Table 1: Key Characteristics of Physical and Chemical Cues

| Characteristic | Topographical Guidance | Immobilized Ligands |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Nature | Physical, mechanical | Biochemical, molecular |

| Sensing Mechanism | Mechanosensing; whole-cell response | Receptor-ligand binding (e.g., integrins) |

| Typical Features | Grooves, ridges, fibers, pores [10] | Laminin, Poly-D-Lysine, RGD peptides [11] |

| Key Cellular Process | Contact guidance; cytoskeletal alignment [9] | Focal adhesion formation; signal transduction [9] |

| Spatial Presentation | Often anisotropic or isotropic patterns [10] | Can be patterned or homogeneous |

Troubleshooting Guides and FAQs

Substrate Preparation and Coating

Issue: Neurons are piling into clumps and not adhering evenly to the substrate.

- Potential Cause: Degradation of the coating substrate.

- Solution:

- If using Poly-L-Lysine (PLL), which is susceptible to enzymatic degradation, switch to the more stable Poly-D-Lysine (PDL) [11].

- For persistent issues, consider switching to a non-peptide alternative like dendritic polyglycerol amine (dPGA), which is highly resistant to degradation because it lacks peptide bonds [11].

Issue: Poor neuronal attachment or neurite outgrowth on fabricated topographies.

- Potential Cause: Incompatible surface chemistry or insufficient coating on the topographical features.

- Solution:

- Ensure your topographical substrate (e.g., PDMS, silicon) is properly sterilized and coated with an adhesion-promoting molecule like PDL or laminin before seeding cells [10].

- The coating protocol may need optimization for complex 3D structures to ensure uniform coverage.

Cell Culture and Health

Issue: Low cell viability or unhealthy neuronal cultures after seeding.

- Potential Causes and Solutions:

- Dissection Damage: For primary neurons, use embryonic tissue (e.g., E17-19 in rats) and gentle mechanical trituration during dissociation. Consider using papain instead of trypsin for digestion to reduce RNA degradation [11].

- Incorrect Plating Density: Plate cells at an appropriate density. For rat primary hippocampal neurons, a standard density for histology is 25,000 - 60,000 cells/cm² [11].

- Suboptimal Medium: Use a serum-free medium like Neurobasal supplemented with B27 and GlutaMAX to support neurons while minimizing glial overgrowth [11].

Issue: Excessive glial cell contamination in primary neuronal cultures.

- Potential Cause: Proliferation of non-neuronal cells from the dissected tissue.

- Solution: Use culture media optimized for neurons (e.g., Neurobasal/B27). If high purity is critical, a low concentration of cytosine arabinoside (AraC) can be used to inhibit glial proliferation, but be aware of its potential neurotoxic side effects [11].

Experimental and Assay Outcomes

Issue: Neurons are not aligning with grooved topographical patterns as expected.

- Potential Causes and Solutions:

- Feature Size Mismatch: The dimensions of the grooves may not be optimal. Test a range of groove widths and depths (from nano- to micro-scale), as neuronal response is highly dimension-dependent [9] [10].

- Anisotropic vs. Isotropic Cues: Verify that your pattern is anisotropic (directionally dependent, like parallel grooves). Neurons will not align on isotropic topographies (e.g., random pits or posts) [10].

Issue: High variability in neurite outgrowth measurements.

- Potential Cause: Inconsistent quantification methods.

- Solution: Implement a standardized, quantitative method for assessment. Common metrics include:

Table 2: Quantitative Metrics for Assessing Neuronal Response

| Metric | Description | Typical Measurement Method |

|---|---|---|

| Neurite Length | Average length of cellular extensions per cell [9] | Fluorescence microscopy & image analysis |

| Alignment Angle | Angle of neurite outgrowth relative to the topographical cue [9] | Circular statistics; angular binning |

| Branching Degree | Number of branch points per neurite [9] | Skeletonization of neurite traces |

| Adhesion Strength | Percentage of cells that remain attached after gentle washing [9] | Cell counting pre- and post-wash |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Creating and Coating Microgrooved Substrates for Contact Guidance Studies

Methodology Summary (based on common practices from literature [10]):

- Substrate Fabrication: Microgrooves are typically fabricated on silicon or polymer surfaces (e.g., PLGA, PDMS) using techniques like photolithography or replica molding.

- Sterilization: Sterilize substrates by immersion in 70% ethanol for 15-30 minutes, followed by exposure to UV light for at least 1 hour.

- Surface Coating:

- Prepare a sterile aqueous solution of Poly-D-Lysine (PDL) at a concentration of 0.1 mg/mL.

- Cover the entire surface of each substrate with the PDL solution.

- Incubate at 37°C for a minimum of 1 hour, or at room temperature overnight.

- Aspirate the PDL solution and wash the substrates three times with sterile distilled water.

- Allow substrates to air dry completely in a sterile environment before cell seeding.

Protocol 2: Culturing Primary Hippocampal Neurons for Outgrowth Assays

Methodology Summary [11]:

- Dissection: Dissect hippocampal tissue from embryonic day 17-19 (E17-E19) rat pups.

- Dissociation: Gently dissociate the tissue using a papain-based dissociation system or gentle mechanical trituration with a fire-polished Pasteur pipette. Avoid bubbles to prevent cell shearing.

- Plating:

- Resuspend the cell pellet in pre-warmed, serum-free neuronal culture medium (e.g., Neurobasal Medium supplemented with B27 and GlutaMAX).

- Count cells and plate at the desired density (e.g., 25,000 - 60,000 cells/cm² for histology) onto pre-coated substrates.

- Maintenance:

- Conduct half-medium changes every 3-7 days to replenish nutrients.

- Maintain cultures in a humidified incubator at 37°C with 5% CO₂.

Signaling Pathway and Experimental Workflow Diagrams

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Reagent Solutions for Neuronal Cell Culture and Substrate Engineering

| Reagent/Material | Function | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Poly-D-Lysine (PDL) | Positively charged polymer coating that promotes neuronal attachment to glass or plastic surfaces [11]. | Standard substrate coating for 2D cultures and 3D topographies. |

| Laminin | Extracellular matrix protein that engages integrin receptors; promotes robust neurite outgrowth [9]. | Coating for enhanced differentiation and outgrowth assays. |

| Neurobasal Medium | Serum-free medium optimized for the long-term health of primary neurons [11]. | Base medium for maintaining hippocampal and cortical cultures. |

| B27 Supplement | Defined serum-free supplement containing hormones, antioxidants, and other neuronal survival factors [11]. | Added to Neurobasal Medium to support neuronal growth and minimize glial proliferation. |

| Cytosine Arabinoside (AraC) | Antimitotic agent that inhibits DNA synthesis; used to control glial cell proliferation [11]. | Added to cultures for short periods to obtain highly pure neuronal populations. |

| Papain Dissociation System | Enzyme-based system for gentle tissue dissociation, minimizing damage to sensitive neuronal cells [11]. | Preferred over trypsin for dissociating embryonic brain tissue. |

The Impact of Substrate Stiffness and Surface Energy on Neuronal Adhesion

Core Concepts: Stiffness and Surface Energy

The mechanical and physical properties of a cell culture substrate are critical instructive cues for neuronal cells. Substrate stiffness, typically measured as Young's modulus (E) in kilopascals (kPa) or megapascals (MPa), directly influences neuronal adhesion, viability, neurite outgrowth, and network formation. Cells sense this stiffness through a process called mechanotransduction. Simultaneously, surface energy, a property influenced by surface chemistry and nanoscale topography, governs protein adsorption and the initial cell-to-substrate attachment. An optimal combination of these parameters is essential for successful neuronal culture experiments.

The table below summarizes the primary effects of these two parameters on neuronal phenotypes.

Table 1: Key Effects of Substrate Stiffness and Surface Energy on Neurons

| Parameter | Key Effects on Neuronal Cells | Recommended Range / Type |

|---|---|---|

| Substrate Stiffness | - Soft, brain-like stiffness (∼0.1-1 kPa) promotes neurite branching and neuronal network activity [12] [13].- Stiffer substrates (∼GPa range of plastic) enhance neural stem cell differentiation and synaptic connectivity in hippocampal networks [12].- Very soft substrates (∼0.5 kPa) can select for neuronal over glial cell growth [14]. | 0.1 kPa - 5 kPa (to mimic brain parenchyma) [15] [12] |

| Surface Energy / Chemistry | - Disordered, nanoscale heterogeneities (e.g., mixed CH3/OH groups) promote robust PC12 cell adhesion and spontaneous differentiation [16].- High-energy surfaces (e.g., OH-terminated) and very low-energy surfaces (e.g., ordered CH3-terminated) can resist cell adhesion [16].- Chitosan serves as a effective adhesion factor supporting neuronal differentiation and maturation of hiPSCs [17]. | Nanoscale chemical heterogeneities; specific coatings (e.g., Chitosan, PDL/Laminin) [16] [18] [17] |

| Coatings | - Poly-D-lysine (PDL) with laminin is highly effective for PC-12 cell attachment under mechanical stress [18].- The optimal coating protocol (mixture vs. sequential layers) can be cell-type dependent [18]. | Cell-type specific (e.g., PDL/Laminin mixture for PC-12; sequential coating for RGCs) [18] |

Troubleshooting Guides & FAQs

Frequently Asked Questions

Q1: My primary neurons are detaching during my experiments, especially when I change the media. What could be the cause and how can I improve adhesion?

- A: This is a common issue often related to suboptimal substrate coating or excessive mechanical stress.

- Verify Your Coating: Ensure you are using an appropriate coating. A mixture of Poly-D-Lysine (PDL) and Laminin has been shown to provide excellent attachment for neuronal cells, even under mechanical stimulation [18]. Note that the best coating strategy (e.g., a mixture vs. sequential layers) may depend on your specific cell type [18].

- Check Coating Protocol: Confirm that your coating reagents are fresh and that you are following the recommended concentrations and incubation times. Inadequate washing after coating can also leave toxic residues.

- Minimize Fluid Shear: When changing media, avoid pipetting directly onto the cell layer. Add and remove media gently from the side of the culture vessel.

Q2: I am trying to mimic the brain's mechanical environment, but my neurite outgrowth is poor. What substrate stiffness should I be using?

- A: Neurons are highly sensitive to stiffness, and a mismatch can inhibit outgrowth.

- Target Brain-Like Stiffness: For most neuronal cultures, aim for a soft substrate with a Young's modulus between 0.1 kPa and 5 kPa to mimic the mechanical properties of brain parenchyma [15] [12] [14].

- Use Appropriate Materials: Standard tissue culture plastic (∼GPa) is far too rigid. Use tunable hydrogels like polyacrylamide (PA) or polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS) to achieve the desired softness [15] [12] [14].

- Confirm Stiffness Experimentally: Do not rely solely on vendor specifications or recipes. Use Atomic Force Microscopy (AFM) or other methods to confirm the elastic modulus of your prepared substrates.

Q3: My neuronal networks seem less active than expected. How can substrate properties influence network activity and synaptic function?

- A: Substrate properties directly modulate electrophysiological maturity and network connectivity.

- Stiffness and Calcium Signaling: Culturing hippocampal neurons on stiffer PDMS substrates (∼457 kPa) enhances voltage-gated calcium channel currents, increases the amplitude and frequency of spontaneous calcium oscillations, and strengthens excitatory synaptic connectivity and transmission compared to softer substrates (∼46 kPa) [12].

- Surface Topography and Clustering: Surfaces with nanoscale roughness can promote the formation of highly interconnected neuronal networks with "small-world" topological properties, which are associated with enhanced computational efficiency [13]. Ensuring your surface promotes cell clustering may improve overall network activity.

Q4: I am differentiating stem cells into neurons. Does the substrate only affect final maturation, or also the initial differentiation?

- A: The substrate plays an instructive role from the very beginning. The mechanical and chemical cues are critical for guiding stem cells toward a neuronal lineage.

- Stiffness Guides Fate: Soft substrates (0.1-1 kPa) that mimic the brain have been shown to promote the neuronal differentiation of human mesenchymal stem cells (hMSCs), while stiffer substrates promote muscle or bone cell fates [19].

- Surface Chemistry is Key: Beyond stiffness, the surface chemistry is vital for initial attachment and subsequent differentiation. Materials like Chitosan have been demonstrated to support the adhesion and early-stage neuronal differentiation of human induced pluripotent stem cells (hiPSCs) as effectively as standard matrices like Matrigel [17].

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Fabricating and Characterizing Tunable PDMS Substrates for Stiffness Studies

This protocol outlines the creation of PDMS substrates with stiffnesses relevant to neuronal research [15] [12] [13].

Workflow Diagram: Creating PDMS Substrates

Materials:

- SYLGARD 184 Silicone Elastomer Kit (Dow Corning)

- Scale and mixing vessels

- Vacuum desiccator or centrifuge for degassing

- Oven (65°C)

- Molds (e.g., Petri dishes)

- Oxygen plasma cleaner (optional, for surface activation)

- Coating solutions (e.g., Poly-D-Lysine, Laminin)

Step-by-Step Method:

- Mixing: Thoroughly mix the PDMS elastomer base and curing agent in the desired weight-to-weight ratio. To achieve softer substrates, use a higher base-to-curing agent ratio. For example:

- Degassing: Place the mixed PDMS in a vacuum desiccator until all air bubbles are removed. This ensures uniformity.

- Curing: Pour the degassed mixture into your desired mold and cure in an oven at 65°C for at least 2 hours. Thicker layers may require longer curing times.

- Surface Preparation: After curing, peel the PDMS substrates from the mold. To render the surface hydrophilic for coating, treat with oxygen plasma for 1-2 minutes.

- Coating: Immediately after plasma treatment, coat the substrates with your chosen adhesion factors (e.g., PDL, Laminin, or their mixture) following standard sterile protocols.

- Validation: It is critical to validate the stiffness of your final substrates using techniques like Atomic Force Microscopy (AFM) or rheology.

Protocol 2: Isolating and Culturing Primary Neurons on Engineered Substrates

This protocol describes the general process for obtaining and maintaining primary neuronal cultures, a cornerstone of neuroscientific research [20].

Materials:

- Brain tissue from rodent (e.g., E18 rat or postnatal mouse pups)

- Dissection tools

- Enzymes: Papain or Trypsin

- Dissociation solution (e.g., HBSS)

- Cell strainers (70 µm, 40 µm)

- Coated substrates (from Protocol 1)

- Neuronal culture medium (e.g., Neurobasal with B-27 supplement)

Step-by-Step Method:

- Dissection: Rapidly and carefully dissect the desired brain region (e.g., hippocampus, cortex) in ice-cold, oxygenated dissection buffer.

- Meninges Removal: Remove the meninges completely, as they contain non-neuronal cells that can contaminate the culture.

- Tissue Dissociation:

- Mechanically mince the tissue into small pieces with a scalpel.

- Incubate the tissue pieces in a pre-warmed enzymatic solution (e.g., Papain, 20 U/mL) for 20-30 minutes at 37°C to digest extracellular matrix proteins.

- Gently triturate the tissue 10-15 times using a fire-polished Pasteur pipette to create a single-cell suspension.

- Cell Separation:

- Pass the cell suspension through a 70 µm cell strainer to remove large clumps.

- Optionally, use a Percoll gradient or immunomagnetic beads (e.g., against CD11b for microglia depletion) to further purify the neuronal population [20].

- Plating and Culture:

- Centrifuge the cell suspension, resuspend the pellet in complete neuronal medium, and count the cells.

- Plate the cells at the desired density onto your pre-coated substrates.

- Maintain cultures in a 37°C, 5% CO2 incubator. Change half of the medium every 3-4 days.

Signaling Pathways & Mechanotransduction

The beneficial effects of soft, brain-like substrates on neural cells are mediated by specific intracellular signaling pathways. Research indicates that the EGFR/PI3K/AKT pathway is a key mediator.

Diagram: Signaling Pathway on Soft Substrates

RNA-Seq and bioinformatics analysis on PC12 cells have confirmed that the promoting effects of soft substrates are linked to the upregulation of the EGFR/PI3K/AKT pathway. This leads to improved cell viability, cell cycle progression, and enhanced neuroprotective effects of chemicals [15].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

Table 2: Key Reagents and Materials for Neuronal Substrate Research

| Item | Function / Application in Research | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| PDMS (Polydimethylsiloxane) | A tunable elastomer for creating substrates of varying stiffness [15] [12] [13]. | Stiffness is controlled by the base-to-crosslinker ratio; requires surface activation (plasma) for coating. |

| Polyacrylamide (PA) Gels | Hydrogel for creating very soft, biologically relevant substrates (0.1 - 50 kPa) [14]. | Stiffness tuned by acrylamide/bis-acrylamide ratio; requires functionalization with adhesion ligands. |

| Poly-D-Lysine (PDL) | A positively charged polymer that coats surfaces to enhance neuronal attachment [18]. | Often used as a base coating; can be used alone or in combination with other proteins like laminin. |

| Laminin | An extracellular matrix protein that promotes neurite outgrowth and strong cell adhesion [18]. | Frequently used in combination with PDL. Optimal concentration and combination are cell-type dependent. |

| Chitosan | A natural biopolymer that serves as an effective adhesion factor for stem cell-derived neurons [17]. | Presents a viable alternative to animal-derived matrices like Matrigel for hiPSC neuronal differentiation. |

| Enzymes (Papain/Trypsin) | Used for the enzymatic digestion of tissue to isolate primary cells [20]. | Concentration and incubation time must be optimized to balance cell yield and viability. |

Troubleshooting Guides and FAQs

Frequently Asked Questions

Q1: My conducting polymer film is delaminating from the electrode substrate. What could be causing this and how can I improve adhesion?

A: Delamination is frequently caused by poor substrate preparation or overly rapid polymerization. Ensure your working electrode (e.g., Pt, ITO glass) is thoroughly cleaned by sequential sonication in solvents like hexane, methanol, and methylene chloride [21]. For electrodeposition, use a controlled technique like cyclic voltammetry rather than a constant high potential, which can create mechanically unstable films. Incorporating an adhesion layer or using dopants that improve interfacial properties can also enhance stability [22].

Q2: I am not observing the expected increase in neurite outgrowth despite electrical stimulation. What are the critical parameters to verify?

A: First, confirm your polymer is in its conductive (oxidized) state and that the electrical stimulus is properly applied. Key parameters include:

- Stimulation Setup: Use a three-electrode configuration with your polymer film as the working electrode. A common effective protocol is a steady, low potential (e.g., 100 mV) applied for several hours (e.g., 2h) [21].

- Cell Condition: Ensure cells are responsive. For PC-12 cells, "prime" them with Nerve Growth Factor (NGF, e.g., 25 ng/ml) for 24 hours prior to seeding and maintain NGF in the medium during experiments [21].

- Polymer Characterization: Verify that your film has a favorable fibrillar or nanostructured morphology, which is known to provide topographical cues that synergize with electrical stimulation [22].

Q3: The conductivity of my PANI-based coating is low under physiological conditions (pH ~7.4). How can I address this?

A: The high conductivity of pure PANI is primarily observed in acidic environments. A common and effective strategy is to create a hybrid structure by depositing a second polymer, such as PEDOT, over the PANI layer. This PEDOT layer can maintain stable conductivity at physiological pH while leveraging the beneficial cellular properties of PANI [22].

Q4: My polymer films are non-porous and show poor cellular integration. How can I improve the morphology for neural interfaces?

A: A non-porous, smooth surface limits tissue integration. To create a favorable 3D structure:

- Explore electrochemical synthesis parameters that lead to the formation of fibrillar nanostructures [22].

- Consider using sequential deposition of two different conducting polymers (e.g., PANI followed by PEDOT), which can naturally form a fibrous, high-surface-area network during synthesis [22].

Experimental Protocols for Key Experiments

Protocol 1: Electrodeposition of Hybrid PANI-PEDOT Films on Pt Electrodes

This protocol is adapted from the synthesis of hybrid coatings that demonstrated superior electrochemical properties and support for neural outgrowth [22].

- Setup: Use a three-electrode system with a Pt-coated substrate as the working electrode, an Ag/AgCl reference electrode, and a Pt-coated titanium rod as the auxiliary/counter electrode.

- Polyaniline (PANI) Deposition: Electrochemically polymerize aniline from an acidic aqueous solution onto the Pt working electrode. Use cyclic voltammetry (CV), initiating the polymerization at a potential of 0.9 V vs. Ag/AgCl. Monitor the development of characteristic redox peaks during the process [22].

- PEDOT Deposition: Subsequently, deposit PEDOT over the PANI layer. The sequential deposition of these two polymers results in the formation of a coating with a fibrillar morphology [22].

- Characterization: Characterize the resulting hybrid film. Expected outcomes include moderate hydrophilicity (contact angle around 49 ± 7°), low impedance (165 ± 6 Ω at 1 kHz), and high capacitance (19.9 mC/cm²) [22].

Protocol 2: In Vitro Neurite Outgrowth Assay with Electrical Stimulation

This protocol is based on classic and contemporary methods for assessing the biofunctionality of conductive substrates [21] [22].

- Cell Culture:

- Use rat PC-12 cells or primary neural cells (e.g., rat-derived embryonic ventral mesencephalon cells).

- For PC-12 cells, culture in DMEM supplemented with horse serum and fetal bovine serum. "Prime" the cells by adding 25 ng/ml of NGF 24 hours before seeding onto the polymer films to induce a neuronal phenotype [21].

- Electrical Stimulation:

- After cells have attached and spread on the polymer film for 24 hours, apply an electrical stimulus.

- Use the conductive polymer film as the anode. Place a cathode (e.g., a gold wire) at the opposite end of the culture well.

- Apply a constant potential of 100 mV for 2 hours using a potentiostat. Maintain cells in a CO2 incubator during stimulation [21].

- Analysis:

- After a further incubation period (e.g., 24 hours post-stimulation), fix the cells and analyze neurite outgrowth.

- Use image analysis software to measure neurite lengths. A successful experiment on a polymer like polypyrrole should show a statistically significant increase in median neurite length compared to unstimulated controls (e.g., ~18.1 μm vs. ~9.5 μm) [21].

Data Presentation

Table 1: Electrochemical and Physical Properties of Neural Interface Coatings

This table summarizes key quantitative data from research on conductive polymer coatings, providing benchmarks for your own experimental results.

| Polymer Material | Impedance (at 1 kHz) | Capacitance | Contact Angle | Key Morphological Feature | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hybrid PANI-PEDOT | 165 ± 6 Ω | 19.9 mC/cm² | 49° ± 7° | Fibrillar morphology | [22] |

| PEDOT:PSS | Information Not Provided | Information Not Provided | Relatively non-porous surface | [22] |

Table 2: Quantitative Neurite Outgrowth Results

This table compares the effects of different conductive polymer substrates and electrical stimulation on neurite extension.

| Experimental Condition | Cell Type | Median Neurite Length | Stimulation Details | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Polypyrrole (PP) with Electrical Stimulation | Rat PC-12 | 18.14 μm (n=5643) | 100 mV for 2 hours | [21] |

| Polypyrrole (PP) Control (No Stimulation) | Rat PC-12 | 9.5 μm (n=4440) | None | [21] |

| Tissue Culture Polystyrene Control | Rat PC-12 | ~9.5 μm | None | [21] |

| Hybrid PANI-PEDOT Coating | Rat embryonic ventral mesencephalon | Supported neural outgrowth and adhesion | Information Not Provided | [22] |

The Scientist's Toolkit

Research Reagent Solutions

This table lists essential materials used in the featured experiments for developing and testing conductive polymer-based neural interfaces.

| Reagent / Material | Function / Purpose | Example from Research |

|---|---|---|

| PEDOT & Polyaniline (PANI) | Intrinsically Conductive Polymers (ICPs) used to create electroactive coatings that reduce impedance and provide topographical/electrical cues. | Sequential deposition creates a hybrid fibrillar structure [22]. |

| Polypyrrole (PPy) | An electrically conductive polymer used as a substrate to apply electrical stimulation directly to cells. | Oxidized polypyrrole films served as the anode for electrical stimulation [21]. |

| Nerve Growth Factor (NGF) | A neurotrophic factor that induces differentiation of certain cell types (like PC-12) into a neuronal phenotype, enabling neurite outgrowth. | Used to "prime" PC-12 cells at 25 ng/ml 24h before seeding [21]. |

| Indium Tin Oxide (ITO) Glass | A transparent, conductive substrate used for the electrochemical synthesis of polymer films and for in vitro microscopy. | Served as the working electrode for polypyrrole film deposition [21]. |

| Poly(styrenesulfonate) - PSS | A dopant ion used during polymerization to incorporate negative charges, achieving charge neutrality and influencing properties like wettability. | Used as the dopant for polypyrrole synthesis [21]. |

| Pt-coated Substrates | A highly conductive, inert working electrode for electrodeposition of polymers and subsequent use as a neural interface. | Used as the base electrode for creating PANI-PEDOT hybrid films [22]. |

Experimental Workflow and Signaling Visualization

Experimental Workflow for Conductive Polymer Neuro-Interface

Pathways to Neural Integration

The Critical Role of Glial Co-culture in Long-Term Neuronal Health and Network Integrity

Troubleshooting Guides

Poor Neuronal Health and Survival in Co-culture

Problem: Neurons show poor attachment, unhealthy morphology, or cell death after several days in co-culture.

| Possible Cause | Diagnostic Steps | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Insufficient trophic support from glial cells | Measure BDNF, GDNF, or NGF levels in medium; check glial cell health and density [23]. | Pre-condition medium with healthy astrocytes; ensure proper glial cell ratio (typically 1:1 to 1:10 neuron:glia) [24]. |

| Pro-inflammatory glial activation | Check for elevated IL-6, TNF-α, or nitric oxide in medium; assess microglial morphology (amoeboid vs. ramified) [25] [26]. | Use lower microglia proportions; induce M2 anti-inflammatory phenotype with IL-4 (10-20 ng/mL) [23] [26]. |

| Inadequate cell contact or distance | Verify cell proximity (<500 µm for contact-dependent effects); check compartment connectivity in microfluidic devices [25]. | Adjust co-culture geometry; use microfluidic platforms with 800-1200 µm long microchannels to permit process extension [25]. |

Prevention Tips:

- Always use mitomycin C (1 µg/mL, 12-16 hours) or similar anti-mitotic treatment on proliferative cells (e.g., Schwann cells, astrocytes) before co-culture to prevent overgrowth [27].

- For 3D systems, optimize hydrogel composition (e.g., 2.0 mg/mL Collagen I) to support both neuronal and glial viability [28].

Insufficient Neurite Outgrowth and Network Formation

Problem: Neurons survive but show limited neurite extension, branching, or functional synaptic connections.

| Possible Cause | Diagnostic Steps | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Lack of extracellular matrix cues | Immunostain for laminin, fibronectin; test neurite outgrowth on ECM-coated substrates alone [23]. | Use engineered silk fibroin or collagen I hydrogels to provide guided growth paths [23] [28]. |

| Deficient neuronal activity | Perform Ca2+ imaging or electrophysiology to check spontaneous activity [29]. | Maintain physiological activity with 5-15 spikes per burst via optimized culture conditions; avoid complete silencing [29]. |

| Improper glial maturation | Check for key glial markers: GFAP (astrocytes), Iba1 (microglia), MBP (oligodendrocytes) [25] [26]. | Differentiate glial cells fully before co-culture (e.g., 30+ days for astrocytes); use validated protocols [25]. |

Prevention Tips:

- Include ascorbic acid (50 µg/mL) in the medium to promote myelination and neurite ensheathment [27].

- For basal forebrain neurons co-cultured with hippocampal neurons, the target-derived trophic support significantly promotes BFCNs growth and axon extension (reaching 1681.9 ± 351.8 µm by week 5) without exogenous growth factors [28].

Uncontrolled Glial Activation and Neuroinflammation

Problem: Glial cells exhibit excessive pro-inflammatory responses, damaging neurons.

| Possible Cause | Diagnostic Steps | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Unintended endotoxin contamination | Test for LPS in media/components; check for elevated TNF-α, IL-1β [25]. | Use endot-free reagents; include polymyxin B (1-5 µg/mL) in some experiments as control. |

| Over-stimulation with inflammatory agents | Measure multiple cytokines (pro- and anti-inflammatory); check C3 complement levels [25]. | Titrate stimuli carefully: use LPS at 10-100 ng/mL, TNF-α/IL-1β at 10-50 ng/mL for 24h max [25]. |

| Loss of homeostatic glial functions | Assess synaptic phagocytosis; measure TGF-β, IL-10 levels [25] [23]. | Include TGF-β (2 ng/mL) to promote homeostatic microglia; use serum-free conditions to reduce baseline activation. |

Prevention Tips:

- Characterize glial activation states comprehensively—don't rely on single markers. Include both M1 (CD68, IL-6) and M2 (Arg1, IL-10) markers [26].

- In microglia-astrocyte co-cultures, TNF-α/IL-1β stimulation increases IL-10, suggesting complex cross-talk [25].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is the optimal neuron-to-glia ratio for long-term co-culture? The ideal ratio depends on the specific research goals and cell types. For microglia-neuron interactions, start with lower ratios (1:5 to 1:10) to prevent excessive neuroinflammation. For astrocyte-neuron co-cultures, 1:1 to 1:3 ratios often work well. In a 3D vascularized tri-culture model, the proportion of M2 microglia supported neurovascular maturation, while M1 microglia were strongly inhibitory [23]. Always conduct a ratio optimization experiment for your specific system.

Q2: How can I maintain co-cultures for extended periods (≥1 month)? Successful long-term culture requires:

- Using anti-mitotic treatment (e.g., mitomycin C) on proliferative glial cells before co-culture [27]

- Implementing 3D hydrogel systems (e.g., Collagen I) that better mimic the brain microenvironment [28]

- Regular half-medium changes (weekly) to remove waste while preserving trophic factors [28]

- Avoiding repeated mechanical disruption; use transwell or microfluidic systems for separation [25] [26]

Q3: How do I distinguish between direct cell-contact effects and soluble factor-mediated effects? Several experimental approaches can separate these mechanisms:

- Use transwell systems (0.4-1.0 µm pores) to permit soluble factor exchange but prevent physical contact [26]

- Implement microfluidic platforms with microtunnels that allow process extension but not cell migration [25]

- Condition medium from one cell type and apply to another [30]

- For lipid transfer studies, a "sandwich" co-culture system with separate coverslips has been successfully used [30]

Q4: What are the key markers to verify functional neuron-glia interactions? Essential markers include:

Table: Key Verification Markers for Functional Neuron-Glia Interactions

| Interaction Type | Structural Markers | Functional Assays | Signaling Molecules |

|---|---|---|---|

| Neuron-Astrocyte | GFAP, βIII-tubulin, GLAST | Glutamate uptake, neuronal survival | BDNF, GDNF, NGF, SDF-1/CXCR4 [23] |

| Neuron-Microglia | Iba1, NeuN, P2Y12 | Phagocytosis, cytokine secretion | IL-6, TNF-α, IL-10, C3 complement [25] [26] |

| Neuron-Oligodendrocyte | MBP, neurofascin, MOG | Myelin formation, conduction velocity | BDNF, NT-3, CNTF [27] |

| Overall Network | Synaptophysin, PSD-95 | Ca2+ imaging, MEA recording | Spontaneous activity patterns [29] |

Q5: How can I model neuroinflammatory conditions in co-culture? Controlled neuroinflammation can be induced using:

- LPS (10-100 ng/mL for 24 hours) to trigger classic microglial activation [25]

- Cytokine mixtures (TNF-α + IL-1β, 10-50 ng/mL each) to simulate neuroinflammatory environments [25]

- Poly I:C (a viral mimetic) to model maternal immune activation effects on neural development [26]

- Importantly, coculture conditions themselves can modulate inflammatory responses—LPS stimulation in microglia-astrocyte cocultures induced lower secretion of several inflammatory mediators compared to monocultures [25]

Table: Cytokine Secretion Profiles in Glial Co-culture Systems Under Inflammatory Stimulation

| Cell Culture Configuration | Stimulus | IL-6 (pg/mL) | TNF-α (pg/mL) | IL-10 (pg/mL) | Nitric Oxide (µM) | Key Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Microglia monoculture | LPS (100 ng/mL) | 1250 ± 320 | 980 ± 215 | 45 ± 12 | 28 ± 6 | Strong pro-inflammatory response [25] |

| Astrocyte monoculture | TNF-α/IL-1β (50 ng/mL) | 680 ± 145 | 25 ± 8 | 22 ± 7 | 5 ± 2 | Cell-type specific response [25] |

| Microglia-Astrocyte coculture | LPS (100 ng/mL) | 650 ± 185 | 510 ± 135 | 85 ± 20 | 15 ± 4 | Dampened inflammatory response [25] |

| Microglia-Astrocyte coculture | TNF-α/IL-1β (50 ng/mL) | 420 ± 125 | 30 ± 10 | 110 ± 25 | 8 ± 3 | Enhanced anti-inflammatory signaling [25] |

| SIM-A9 microglia | Poly I:C | 450 ± 95 | 320 ± 75 | N/R | 12 ± 3 | Supports NSPC differentiation initially [26] |

Table: Neuronal Morphometric Outcomes in Different Co-culture Systems

| Co-culture System | Neurite Length (µm) | Branching Complexity | Synapse Density | Long-term Survival | Key Requirements |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BFN-HPC 3D coculture | 1681.9 ± 351.8 (axons by week 5) | High, elaborate arbors | Functional connections | >2 months | Collagen I hydrogel, exogenous factor-free [28] |

| LPeD1 neurons with CM | Varies with activity patterns | Higher with >10 spikes/burst | Activity-dependent | Several weeks | Physiological activity patterns essential [29] |

| ND7/23-IFRS1 | Sufficient for myelination | Moderate | Myelinated contacts | 21+ days | Ascorbic acid, NGF, CNTF [27] |

| hiNSCs with M2 microglia & hVOs | Enhanced outgrowth | Improved with M2 microglia | Increased | Several weeks | SDF-1/CXCR4 signaling [23] |

Experimental Protocols

Purpose: To investigate inflammatory interactions between microglia and astrocytes while maintaining distinct microenvironments.

Materials:

- Human iPSC-derived microglia and astrocytes

- Microfluidic coculture platform with interconnecting microtunnels

- LPS, TNF-α, IL-1β for inflammatory stimulation

- Immunocytochemistry reagents (Iba1, GFAP, C3 antibodies)

- Cytokine ELISA kits (IL-6, TNF-α, IL-10)

Procedure:

- Differentiate microglia and astrocytes from human iPSCs using established protocols

- Seed astrocytes in one compartment and microglia in the other of the microfluidic platform

- Culture for 24-48 hours to allow process extension through microtunnels

- Stimulate with LPS (100 ng/mL) or TNF-α/IL-1β (50 ng/mL each) for 24 hours

- Collect conditioned media for cytokine analysis

- Fix cells for immunocytochemistry (Iba1 for microglia, GFAP for astrocytes, C3 for complement)

- Quantify microglial migration toward astrocyte compartment

Key Considerations:

- This platform enables spontaneous migration of microglia toward astrocytes

- Inflammatory stimulation elicits cell type-specific responses

- LPS stimulation in cocultures induces lower secretion of several inflammatory mediators compared to monocultures

- TNF-α/IL-1β stimulation increases IL-10 in cocultures, suggesting complex crosstalk

Purpose: To examine bidirectional lipid transport between neurons and glia without direct physical contact.

Materials:

- Primary hippocampal neurons and mixed glial cells from postnatal rat pups

- Poly-d-lysine-coated coverslips

- Fluorescently labeled fatty acids (e.g., BODIPY FL C16)

- Fluorescence microscope with imaging software

- ImageJ software with analysis plugins

Procedure:

- Culture primary neurons and glial cells on separate poly-d-lysine-coated coverslips

- Pulse neuronal cultures with fluorescently labeled fatty acids (5-20 µM for 4-24 hours)

- Wash neurons to remove unincorporated fatty acids

- Incubate neuron-covered and glia-covered coverslips together in a "sandwich" configuration

- Fix cells after appropriate incubation period (2-24 hours)

- Image glial cells for fluorescent fatty acid incorporation

- Quantify lipid droplet number, size, and fluorescence intensity using ImageJ

Key Considerations:

- This system allows study of bidirectional lipid transfer

- Can be adapted for different cell types and fatty acid probes

- Control for phagocytosis of cellular debris using appropriate inhibitors

- Lipid droplet formation in astrocytes indicates successful transfer

Research Reagent Solutions

Table: Essential Reagents for Glial Co-culture Experiments

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Function/Purpose | Working Concentration |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cell Sources | Human iPSC-derived microglia/astrocytes [25]; SIM-A9 microglial cell line [26]; IFRS1 Schwann cells [27]; Primary hippocampal/basal forebrain neurons [28] | Provide biologically relevant cells for co-culture | Varies by protocol |

| Soluble Factors | NGF (10 ng/mL) [27]; CNTF (10 ng/mL) [27]; Ascorbic acid (50 µg/mL) [27]; BDNF, GDNF; IL-4 (10-20 ng/mL) for M2 polarization [26] | Promote neuronal survival, differentiation, myelination, and modulate glial phenotype | See specific protocols |

| Inflammatory Stimuli | LPS (10-100 ng/mL) [25]; TNF-α + IL-1β (10-50 ng/mL each) [25]; Poly I:C [26] | Model neuroinflammatory conditions; study glial activation | 24-hour treatment typical |

| Hydrogel/3D Matrix | Collagen I (2.0 mg/mL) [28]; Silk fibroin scaffolds [23]; Matrigel | Provide 3D microenvironment supporting long-term culture and neurovascular organization | Optimize for specific cell types |

| Inhibitors/Treatments | Mitomycin C (1 µg/mL, 12-16h) [27]; Y27632 (5 µM) [27]; Ca2+ channel blockers [29] | Suppress proliferative cells; enhance neurite outgrowth; study activity-dependence | Pre-treatment before co-culture |

| Analysis Reagents | Iba1, GFAP, βIII-tubulin antibodies; C3 complement marker [25]; ELISA kits for cytokines | Characterize cell types, activation states, and functional outcomes | Follow manufacturer protocols |

Signaling Pathways in Glial-Neuronal Communication

This diagram illustrates the SDF-1/CXCR4 signaling axis identified in a 3D vascularized tri-culture system where M2 microglia cooperate with human vascular organoids to promote neuronal differentiation of human-induced neural stem cells [23].

From Theory to Bench: Proven Protocols and Advanced Assay Systems

This technical support guide is framed within a research thesis focused on improving neuronal attachment and neurite outgrowth on substrates. The protocols and troubleshooting advice herein are designed to assist researchers in consistently cultivating two fundamental neuronal models: the PC12 cell line, derived from rat pheochromocytoma, and primary cultures of Dorsal Root Ganglion (DRG) neurons [31] [32]. Optimizing these cultures is critical for reliable research in neurotoxicity, neuroprotection, and drug development.

Section 1: The PC12 Cell Line Model

Background and Applications

The PC12 cell line is one of the most commonly used models in neuroscience research. These cells, derived from a rat adrenal medulla pheochromocytoma, can be differentiated into a neuron-like phenotype using Nerve Growth Factor (NGF), developing extensive neurite outgrowths and expressing characteristic neuronal markers [31] [33]. They are invaluable for studies on neurosecretion, neuroinflammation, and synaptogenesis. It is crucial to know that two main variants are available:

- PC12 (ATCC CRL-1721): Grows in suspension as cell clusters and adheres poorly to non-coated surfaces [31].

- PC12 Adh (ATCC CRL-1721.1): An adherent phenotype that attaches readily to surfaces and has a faster growth rate [31].

Table 1: Key Characteristics of PC12 Cell Line Variants

| Feature | PC12 Cell Line (ATCC CRL-1721) | PC12 Adh Cell Line (ATCC CRL-1721.1) |

|---|---|---|

| Cell Type | Cluster of floating cells | Adherent cells |

| Morphology | Small and irregular shape | Polygonal shape |

| Baseline Culture Medium | RPMI-1640 with 10% DHS, 5% FBS | Ham’s F-12K with 15% DHS, 2.5% FBS |

| Adhesion Requirement | Requires coated surfaces (e.g., collagen) | Adheres well to plastic and coated surfaces |

Detailed Protocol: Culturing and Differentiating PC12 Cells

A. Standard Culture Conditions

- Growth Medium: Use DMEM-Hi supplemented with 15% Fetal Bovine Serum (FBS) [34].

- Substrate Coating: Plate cells on collagen-coated plates to facilitate attachment, especially for the suspension variant [31] [34].

- Coating Protocol: Dilute rat tail collagen (e.g., BT-274) 1:5 in sterile PBS. Add to culture dishes (e.g., 400 µl for a 10 cm dish), spread evenly, and allow to dry overnight in a sterile hood. Coated plates are stable for 2-3 weeks [34].

- Splitting Cells: When 70-90% confluent, split cells at a ratio of 1:5. PC12 cells do not typically require trypsin; they can be dislodged by gently sucking media and using the flow to wash cells off the plate. Always keep at least 20% conditioned media when splitting, as the cells rely on its factors [34].

- Freezing Cells: For a 70-90% confluent 10 cm dish, dislodge cells, collect via low-speed centrifugation, and resuspend in freezing medium (DMEM-Hi with 20% FBS and 10% DMSO). Freeze at -80°C overnight before transferring to liquid nitrogen for long-term storage [34].

B. Differentiation Protocol

- Preparation: Start with cells at 50-70% confluency [34].

- Differentiation Medium: Use growth medium supplemented with 50 ng/mL NGF [34]. The origin of NGF (rat or human) does not significantly impact the outcome [31].

- Medium Changes: Change to fresh NGF-containing media every 2-3 days. When changing, remove only 75% of the old media and replace it with new, pre-warmed media to maintain conditioning [34].

- Timeline: Differentiation is typically complete after 5-7 days for adherent PC12 cells. The traditional suspension variant may require up to 14 days of incubation with NGF to achieve optimal neurite outgrowth [31] [35].

The workflow and key signaling pathway for PC12 differentiation is summarized in the diagram below:

PC12 Troubleshooting Guide & FAQs

Q1: My PC12 cells are not attaching properly. What should I do?

- A: This is common with the traditional suspension variant. Ensure you are using an appropriate coating. Collagen coating is the most versatile, while poly-D-lysine is also effective. For PC12 Adh, coating is less critical, but still recommended for optimal differentiation [31].

Q2: I am not seeing sufficient neurite outgrowth after NGF treatment. How can I improve this?

- A: First, verify your NGF concentration and freshness. A concentration of 50-100 ng/mL is standard. Ensure you are changing the NGF-containing media every 48-72 hours, as the factor degrades. Second, confirm the cell confluency; differentiation is most efficient starting from 50-70% confluency. Finally, for the suspension cell line, be patient, as full differentiation can take up to 14 days [31] [34].

Q3: Which PC12 variant should I use for my neurobiological study?

- A: The traditional PC12 (suspension) line is often preferred for neurobiological studies after NGF differentiation, as it exhibits well-characterized neuronal biomarkers like doublecortin (DCX) and NeuN. The adherent variant (PC12 Adh) does not express DCX and shows atypical cytoplasmic localization of NeuN, the role of which is not fully understood [31].

Section 2: Dorsal Root Ganglion (DRG) Neuron Model

Background and Applications

DRG neurons are primary cells that transmit somatosensory information, including pain, touch, and temperature [36]. Cultures of DRG neurons contain not only neurons but also satellite glial cells and macrophages, providing a more physiologically complex model for studying pain pathways, neuroinflammation, and the effects of inflammatory mediators like Lipopolysaccharide (LPS) [32].

Detailed Protocol: Isolating and Culturing DRG Neurons

This protocol is adapted for postnatal (4-6 week old) rats. For embryonic isolation (e.g., E15), an immunopanning technique can be used for further purification [36].

- Dissection and Dissociation: After euthanasia, quickly dissect out the dorsal root ganglia. Place them in cold, sterile buffer. Clean the ganglia of connecting nerves and root fibers. Enzymatically dissociate the tissue using a solution like collagenase/dispase, typically for 90 minutes at 37°C [32].

- Trituration and Plating: After enzymatic digestion, triturate the ganglia gently using a fire-polished Pasteur pipette to create a single-cell suspension. Plate the cells on poly-D-lysine/laminin-coated coverslips or dishes to promote neuronal attachment [32].

- Culture Medium: Maintain cells in a suitable neurobasal medium supplemented with growth factors (e.g., B27, NGF) and antibiotics [32].

- Experimental Stimulation: Mature DRG cultures can be used for calcium imaging or electrophysiology. To study inflammation, cultures can be stimulated with LPS (1-10 µg/ml) for 2 hours, which induces the release of cytokines like TNF-α and IL-6 and enhances neuronal responses to stimuli like capsaicin [32].

The experimental workflow for DRG neuron culture and stimulation is as follows:

DRG Neuron Troubleshooting Guide & FAQs

Q1: My DRG neuronal yield is low after dissociation. What could be the issue?

- A: The age of the animal impacts neuronal yield and properties. Neurons from younger animals have different electrophysiological properties [37]. Ensure the enzymatic digestion is not overly prolonged and that trituration is gentle to avoid mechanical damage. Using a defined, serum-free medium can help suppress the overgrowth of non-neuronal cells, preserving neurons [32].

Q2: How can I temporarily store or ship live DRG neurons?

- A: Recent research shows that Hibernate A media is excellent for temporary storage. Whole DRGs or dissociated neurons can be stored in this media at 4°C for 4-16 hours (or even >24 hours for shipping) with good recovery of neuronal yield, electrophysiological properties, and capsaicin responses [38].

Q3: The glial cells in my culture are overgrowing the neurons. How can I control this?

- A: The use of cytostatic agents like cisplatin (5-10 µg/ml) can be employed. Cisplatin significantly reduces the number of macrophages and suppresses the growth of satellite glial cells without immediately impairing the vitality or stimulus-induced Ca²⁺ signals of DRG neurons [32].

Section 3: Reagent Toolkit for Neuronal Culture

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents for PC12 and DRG Culture

| Reagent | Function | Application Note |

|---|---|---|

| Collagen | Extracellular matrix protein for cell attachment | Most versatile coating for PC12 cells; crucial for suspension variant [31] [34]. |

| Poly-D-Lysine (PDL) | Synthetic polymer coating to enhance attachment | Good for PC12 Adh cells and for coating dishes for DRG neurons [31]. |

| Nerve Growth Factor (NGF) | Differentiation factor | Induces neuronal phenotype in PC12 cells (50-100 ng/mL). Also a supplement for DRG neuron survival [31] [34]. |

| NGF Origin (Rat vs. Human) | Source of growth factor | Human or rat recombinant NGF are both effective for PC12 differentiation [31]. |

| Lipopolysaccharide (LPS) | Inducer of inflammatory response | Used in DRG cultures (1-10 µg/ml) to model neuroinflammation and study neuron-glia interactions [32]. |

| Hibernate A Media | Preservation medium | Enables temporary cold storage and shipping of live DRG neurons and tissue [38]. |

| Capsaicin | TRPV1 channel agonist | Used to stimulate and identify nociceptive neurons in DRG cultures in Ca²⁺ imaging experiments [32]. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: My neuronal cultures are detaching after about a week. What could be the cause and how can I prevent it?

A1: Neuronal detachment after 7-10 days is a common problem often linked to the instability of adsorbed PLL coatings. A 2023 study demonstrated that covalently grafting PDL to glass coverslips using (3-glycidyloxypropyl)trimethoxysilane (GOPS) significantly improved long-term stability. Neurons on these grafted surfaces showed more dense and extended networks and enhanced synaptic activity compared to standard adsorbed PLL [39] [40] [41].

Q2: What is the difference between single and double-coating with ECMs, and when should I use each method?

A2: The choice depends on your cell type and research goals:

- Single Coating (e.g., PLO or PDL alone): Simpler and faster. However, research on iPSC-derived neurons (iNs) found that single coatings with PDL or PLO resulted in sparse neurite outgrowth and more cell debris compared to laminin or Matrigel [42].

- Double Coating (e.g., PLO/Laminin): Provides a more robust and bioactive substrate. A 2024 systematic evaluation found that double-coating (e.g., PDL+Matrigel) significantly reduced the clumping of iN cell bodies and enhanced neurite outgrowth, neuronal purity, and synaptic marker distribution compared to single coatings [42]. This method is highly recommended for demanding applications like long-term cultures or the differentiation of sensitive cell types like iPSCs [42] [43].

Q3: How does the pH of the PLL solution affect my neuronal culture?

A3: The pH of the PLL solution is critical for the coating density and subsequent neuronal maturation. The same 2023 study found that using an alkaline solution (pH 9.7) for grafting PDL (GPDL9) resulted in superior outcomes. Neurons cultured on GPDL9 developed more mature morphological and functional characteristics, including denser networks and enhanced synaptic activity, compared to those on PDL adsorbed at pH 6 (PDL6) [40] [41].

Q4: I am working with induced pluripotent stem cell (iPSC)-derived neural progenitor cells (NPCs). What is the optimal coating for their differentiation?

A4: For differentiating human iPSC-derived NPCs, a double-coating system is most effective. A common and robust protocol involves [43] [44]:

- Coating with Poly-L-Ornithine (PLO): Use a concentration of 10 µg/mL in PBS or sterile water. Incubate for 24 hours at room temperature.

- Rinsing: Wash the surface three times with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS).

- Coating with Laminin: Apply a solution of 5 µg/mL in PBS. Incubate for at least 16 hours (overnight) at 4°C. This combination provides a positively charged PLO base for strong cell adhesion and a laminin top layer that provides crucial bioactive signals for neurite outgrowth and differentiation.

Troubleshooting Guide

| Problem | Potential Cause | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Poor Cell Attachment | • Inactive or outdated coating solutions.• Incorrect coating concentration.• Inadequate incubation time or temperature. | • Prepare fresh coating solutions and aliquot for single use.• Ensure PLO/PLL concentration is 10-100 µg/mL.• Ensure laminin concentration is 1-10 µg/mL. Follow incubation times strictly [43] [44]. |

| Excessive Cell Clumping | • Suboptimal coating matrix, common in iPSC-derived neuron cultures.• Seeding cells at too high a density. | • Switch to a double-coating strategy (e.g., PDL+Matrigel or PLO/Laminin) to promote even cell distribution and reduce aggregation [42].• Optimize cell seeding density. |

| Weak Neurite Outgrowth | • Lack of bioactive cues in the coating.• Unstable coating leading to detachment. | • Add laminin (1-10 µg/mL) on top of the PLO/PLL base coat to provide essential guidance cues [42] [43].• Consider covalently grafting PLL for a stable, long-lasting substrate [39]. |

| Variability Between Cultures | • Inconsistent coating procedures between users or batches.• Fluctuations in pH during PLL solution preparation. | • Standardize the coating protocol within the lab. Use detailed, written SOPs.• Control the pH of the PLL solution. Using a carbonate buffer at pH 9.7 for grafting can improve reproducibility and outcomes [40] [41]. |

Optimized Coating Protocols and Data

Standard Double-Coating Protocol for NPCs and Primary Neurons

This is a widely adopted and robust method for culturing neural cells.

Protocol: Poly-L-Ornithine (PLO) and Laminin Double Coating [43] [44]

- Surface Preparation: Ensure culture surfaces (e.g., plates, coverslips) are clean and sterile.

- PLO Coating:

- Prepare a 10 µg/mL solution of Poly-L-Ornithine in sterile PBS or ultra-pure water.

- Add sufficient solution to cover the growth surface.

- Incubate for 24 hours at room temperature.

- Rinsing: Aspirate the PLO solution and wash the surface three times with sterile PBS.

- Laminin Coating:

- Prepare a 5 µg/mL solution of Laminin in cold PBS.

- Add the solution to the PLO-coated surface.

- Incubate for a minimum of 16 hours (overnight) at 4°C.

- Preparation for Seeding: Immediately before cell seeding, aspirate the laminin solution. Do not let the surface dry out. Rinse once with PBS or directly add cell suspension in the desired medium.

Advanced Covalent Grafting Protocol for Enhanced Maturation

For experiments requiring long-term stability and superior neuronal maturation, such as electrophysiology or synaptogenesis studies, covalent grafting is superior to simple adsorption.

Protocol: Covalent Grafting of Poly-D-Lysine using GOPS [39] [40]

- Silane Treatment: Expose glass coverslips to (3-glycidyloxypropyl)trimethoxysilane (GOPS) in the gas phase at room temperature to functionalize the surface with epoxy groups.

- PDL Solution Preparation:

- Prepare a PDL solution (e.g., 20 µg/mL) in a 50 mM sodium carbonate buffer.

- Adjust the pH to 9.7 using 1M HCl. This alkaline pH is crucial for the grafting efficiency.

- Grafting Reaction: Apply the PDL solution (pH 9.7) to the GOPS-functionalized coverslips. The epoxy group on GOPS reacts with the primary amines on PDL, creating a stable covalent bond.

- Rinsing and Storage: After incubation, rinse the coverslips thoroughly with ultra-pure water to remove any non-grafted PDL. The coated coverslips can be stored sterilely until use.

Quantitative Coating Parameters

Table 1: Summary of Optimized Coating Parameters from Recent Research

| Coating Method | Coating Material | Concentration | Solvent / Buffer | Incubation Conditions | Key Outcome | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adsorption | Poly-L-Ornithine (PLO) | 10 µg/mL | PBS or H₂O | 24 hours, Room Temperature | Reliable base coat for neural cultures | [43] [44] |

| Adsorption | Laminin | 5 µg/mL | PBS | 16 hours, 4°C | Promotes neurite outgrowth and differentiation | [43] [44] |

| Covalent Grafting | Poly-D-Lysine (PDL) | 20-40 µg/mL | 50 mM Sodium Carbonate, pH 9.7 | Several hours, RT (post-GOPS) | Superior neuronal maturation, denser networks, enhanced synaptic activity | [39] [40] |

| Double Coating | PDL + Matrigel | Standard concentrations | Standard buffers | Standard incubations | Reduced iN clumping, improved neuronal purity & synaptic marker distribution | [42] |

Experimental Workflow and Signaling Pathways

Coating Selection and Application Workflow

This diagram illustrates the decision-making process for selecting and applying the appropriate coating protocol based on experimental goals.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Materials for Neuronal Cell Coating

| Reagent | Function / Role in Coating | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Poly-L-Lysine (PLL) / Poly-D-Lysine (PDL) | Provides a positively charged surface for electrostatic attachment of negatively charged cell membranes. Synthetic PDL is not degraded by cells. | Molecular weight (70-150 kDa common); PLL is biodegradable, PDL is more stable [40]. |

| Poly-L-Ornithine (PLO) | Functions similarly to PLL, providing a positive charge for cell adhesion. Often used as a base coat. | Frequently specified in protocols for iPSC-derived neural cells [43] [44]. |

| Laminin | A major component of the native extracellular matrix (ECM). Provides bioactive ligands (e.g., for integrin receptors) that promote neurite outgrowth, axon guidance, and cell survival. | Sensitive to temperature; handle and store on ice. Often used in combination with PLL/PLO [42] [43]. |

| Matrigel | A complex, reconstituted basement membrane matrix containing laminin, collagen, and other ECM proteins. | Provides a highly bioactive environment. Composition is variable; may not be suitable for all reductionist studies [42]. |

| (3-glycidyloxypropyl)trimethoxysilane (GOPS) | A silane-based coupling agent. Used to covalently link PDL to glass surfaces, creating a highly stable coating. | Its epoxy group reacts with amine groups on PDL and hydroxyl groups on glass. Avoids toxic glutaraldehyde [39] [40]. |

| Sodium Carbonate Buffer | Used to create an alkaline environment (pH 9.7) for the PDL grafting reaction. | High pH is critical for the efficiency of the covalent bonding between GOPS and PDL [40] [41]. |

Technical Troubleshooting Guide: FAQs for Microcontact Printing (µCP)

This section addresses common challenges researchers face when implementing microcontact printing for neuronal patterning, providing targeted solutions to ensure high-quality results.

Table 1: Troubleshooting Common Microcontact Printing Issues

| Problem Phenomenon | Potential Cause | Diagnostic Steps | Solution |

|---|---|---|---|

| Incomplete or faint protein patterns | Stamp not fully inked; insufficient contact pressure; protein solution too dilute [45] | Inspect stamp surface under microscope after inking; verify protein concentration. | Re-ink stamp ensuring full coverage; apply even, firm pressure during printing; concentrate protein solution [45]. |

| Non-specific cell attachment in non-patterned areas | Ineffective passivation of background; residual protein contamination [45] | Incubate a patterned substrate with culture medium (no cells) and check for protein adsorption. | Back-fill with proven anti-fouling molecules like PLL-g-PEG [45]; ensure thorough cleaning of substrates before patterning. |

| Patterned features are blurred or distorted | Over-inking causing excess liquid on stamp features; stamp deformation during contact [45] | Inspect inked stamp for pooling liquid; check stamp integrity and master design. | Blot stamp to remove excess ink; use stiffer PDMS (e.g., higher crosslinker ratio); reduce stamp contact time [45]. |

| Cells detach from adhesive patterns | Weak protein adhesion to substrate; patterned features are too small [46] | Test protein adhesion on unpatterned substrate; try larger patterns as a control. | For glass substrates, apply a thin polystyrene coating to improve protein adhesion [45]; ensure adhesive motifs (e.g., laminin-derived peptides) are properly coupled to the surface [47]. |

| Low resolution or loss of small features (<5 µm) | Resolution limit of PDMS stamp; pattern collapse in the master [45] | Check master integrity under high magnification. | For high-resolution needs, consider direct-write methods like micro photopatterning (µPP) [48]; ensure master is fabricated for small features [45]. |

Essential Protocols for Controlled Neuronal Growth

This section provides detailed, actionable protocols for creating micropatterned substrates, from a standard method to a more advanced, accessible approach.

Standard Protocol: Microcontact Printing of Adhesive Micropatterns

This protocol, adapted from Théry and Piel, details how to create a PDMS stamp and print protein patterns to control cell adhesion [45]. The entire process can be completed in less than 2 hours.

Materials & Reagents:

- Silicon Master: Contains the microfeatures. Can be reused indefinitely [45].

- PDMS (Polydimethylsiloxane): Sylgard 184 is commonly used [45] [46].

- Extracellular Matrix Protein: Fibronectin (50 µg/mL in PBS) or other adhesive proteins (e.g., Laminin-derived peptides [47]).

- Passivation Reagent: PLL-g-PEG (Poly(L-lysine)-g-poly(ethylene glycol)) [49] [45].

- Substrate: Glass coverslips or tissue culture polystyrene dishes [45].

Method:

- Stamp Fabrication:

- Substrate Preparation (for glass coverslips):

- Clean coverslips thoroughly. A thin layer of polystyrene can be applied to glass to enhance protein adhesion and prevent cells from ripping proteins off the surface [45].

- Inking and Printing:

- "Ink" the PDMS stamp by incubating with the protein solution (e.g., fibronectin) for 1 hour [45].

- Dry the stamp with a stream of nitrogen or compressed air to remove excess liquid [45].

- Bring the inked stamp into conformal contact with the substrate for a few seconds to transfer the protein pattern [45] [46].

- Passivation:

- Incubate the substrate with a PLL-g-PEG solution to back-fill the non-printed areas, rendering them resistant to cell attachment [45].

- Cell Seeding:

Advanced Protocol: Low-Cost, Rapid Maskless Photolithography

This modern protocol uses a standard fluorescence microscope to create resin molds for PDMS-based substrates, eliminating the need for a physical mask or cleanroom [50]. It enables design-to-device turnaround within a day.

Materials & Reagents:

- Equipment: Fluorescence microscope with DMD (Digital Micromirror Device) and UV light source (e.g., 395 nm), spin coater [50].

- Consumables: Standard microscope slides, consumer-grade UV-curing 3D printing resin, TMSPMA (adhesion promoter), PDMS [50].

Method:

- Slide Preparation: Clean a microscope slide and coat it with TMSPMA to promote resin adhesion [50].

- Spin Coating: Spin-coat a thin layer of UV resin onto the slide. Control the thickness (z-height) precisely by varying the spin speed [50].

- UV Projection: Place the slide on the microscope stage. Project UV light patterns (designed in computer software) through the DMD onto the resin layer. Use a 20x objective for a good balance between field of view and resolution (~0.7 µm/px) [50].

- Development and Post-Processing: Wash away unexposed resin to reveal the mold. Post-cure the mold with UV light and heat [50].