Solving Low Neuronal Yield: A Researcher's Guide to Optimizing Embryonic Tissue Dissection and Culture

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals tackling the common challenge of low neuronal yield from embryonic tissue dissection.

Solving Low Neuronal Yield: A Researcher's Guide to Optimizing Embryonic Tissue Dissection and Culture

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals tackling the common challenge of low neuronal yield from embryonic tissue dissection. It covers the foundational principles of primary neuron biology, details region-specific optimized protocols for cortex, hippocampus, and hindbrain, and offers a systematic troubleshooting framework for issues from enzymatic digestion to glial contamination. The content also explores advanced validation techniques and comparative analyses with emerging stem cell-based models, synthesizing key strategies to enhance reproducibility, viability, and translational relevance in neuroscience research.

Understanding Primary Neurons: Why Yield and Viability Matter in Translational Research

The Critical Advantages of Primary Neurons Over Immortalized Cell Lines

For researchers troubleshooting low neuronal yield from embryonic tissue dissection, the choice between primary neurons and immortalized cell lines is not merely a matter of convenience—it is a fundamental decision that directly impacts the physiological relevance and translational potential of your findings. While immortalized cell lines offer advantages in scalability and reproducibility, a growing body of evidence highlights their significant limitations in replicating complex neuronal behavior. This technical support article examines the critical advantages of primary neurons and provides practical guidance for overcoming common challenges in their isolation and culture, specifically framed within the context of a thesis addressing low neuronal yield from embryonic tissue dissection.

Key Advantages of Primary Neurons: Beyond Biological Relevance

Superior Physiological Relevance and Native Functionality

Primary neurons maintain the morphology, gene expression patterns, and functional characteristics of their in vivo counterparts, making them significantly more physiologically relevant than immortalized lines [1] [2]. Unlike cancer-derived immortalized cell lines (such as SH-SY5Y neuroblastoma cells), which are optimized for proliferation rather than function, primary neurons develop extensive axonal and dendritic branching, form functional synapses, and establish authentic neuronal networks in culture [3] [4] [5]. This preservation of native functionality is particularly crucial for studying complex neuronal processes such as synaptic transmission, network formation, and neurodegeneration mechanisms.

Retention of Human-Specific Signaling Pathways

The translational gap between animal models and human biology represents a critical challenge in neuroscience research. Primary human neurons retain species-specific signaling pathways that are often absent or altered in immortalized lines [3] [6]. This advantage is exemplified by the high failure rate of CNS-targeted drug candidates (approximately 97% in phase 1 clinical trials never reach market), which reflects fundamental gaps in preclinical model predictivity [3]. When working with non-human primary neurons, selecting appropriate models is essential—for instance, chicken APP exhibits 93% amino acid identity with human APP, with identical Aβ1-42 sequences, making it superior to rodent models for certain Alzheimer's disease studies [7].

Avoidance of Genetic Drift and Phenotypic Instability

Unlike immortalized cell lines that undergo genetic drift and phenotypic changes with continuous passaging, primary neurons maintain genomic and phenotypic stability throughout their finite lifespan [8] [6]. Immortalized lines progressively shift cellular resources toward proliferation functions, potentially compromising their neuronal characteristics [3] [6]. This genetic stability ensures that experimental results obtained with primary neurons more accurately reflect biological reality rather than artifacts of long-term culture.

Appropriate Response to Pharmacological Interventions

Primary neurons demonstrate physiologically relevant responses to pharmacological compounds and toxicological insults, making them invaluable for drug discovery and neurotoxicity studies [9] [6]. Their native receptor composition, signaling machinery, and metabolic pathways remain intact, providing more predictive data for preclinical assessment of therapeutic candidates. This contrasts with immortalized lines, which often exhibit altered response profiles due to their transformed nature [3] [8].

Table 1: Comprehensive Comparison of Primary Neurons vs. Immortalized Cell Lines

| Characteristic | Primary Neurons | Immortalized Cell Lines |

|---|---|---|

| Biological relevance | High - retain native morphology and function [3] [1] | Low - often non-physiological (e.g., cancer-derived) [3] [2] |

| Reproducibility | Moderate (donor-to-donor variability) [1] | High (but prone to genetic drift) [3] [8] |

| Scalability | Limited yield, difficult to expand [3] | Easily scalable [3] [2] |

| Lifespan | Finite (undergo senescence) [1] [2] | Unlimited divisions [8] [2] |

| Species specificity | Human or model organisms available [7] [1] | Often non-human origin [3] |

| Genetic stability | High (no long-term culture artifacts) [6] | Low (subject to genetic drift) [8] [6] |

| Functional synapses | Yes - form mature synaptic connections [4] [5] | Typically limited or absent [3] |

| Cost and accessibility | Higher cost, more difficult to acquire [1] [2] | Lower cost, readily available [2] |

| Technical expertise required | High (specialized handling needed) [4] [9] | Low (easy to culture and maintain) [3] [2] |

| Typical applications | Disease modeling, translational research, mechanistic studies [1] [9] | High-throughput screening, preliminary assays [3] |

Troubleshooting Low Neuronal Yield: A Technical Guide

FAQ: What are the primary factors contributing to low neuronal yield from embryonic tissue dissection?

Several technical factors can significantly impact neuronal yield during the isolation process. Based on optimized protocols from multiple laboratories, the most critical factors include dissection timing, enzymatic dissociation efficiency, and physical trituration techniques [4] [10] [9].

Optimal Developmental Timing

The embryonic stage at dissection profoundly affects both yield and viability. For cortical and hippocampal neurons, the optimal window is E17-E18 for rats and E16-E18 for mice [4] [10] [9]. Earlier timepoints may provide more proliferative precursors, while later timepoints yield more mature neurons but with reduced viability after dissociation. The heterogeneity of older brain tissue also increases the risk of contamination with other cell types such as astrocytes and oligodendrocytes [10].

Enzymatic Dissociation Parameters

The choice of enzyme and incubation conditions directly impacts cell viability. Papain-based dissociation is generally preferred over trypsin for neuronal preparations due to its gentler action on neuronal surfaces [4] [9]. Optimal concentration ranges from 0.5-1mg/mL with incubation times of 10-15 minutes at 37°C [4] [5]. Including DNase I (10μg/mL) in the dissociation solution helps prevent cell clumping by digesting DNA released from damaged cells [4].

Mechanical Trituration Techniques

The physical process of trituration represents a critical step where significant cell loss can occur. Using fire-polished glass Pasteur pipettes with gradually decreasing diameters (from ~750μm to ~675μm) minimizes shear stress [4] [5]. The number of trituration passes should be optimized—typically 10-15 gentle up-and-down motions—until no visible tissue fragments remain [4] [9]. Over-trituration increases mechanical damage, while under-trituration reduces yield.

Table 2: Troubleshooting Guide for Low Neuronal Yield

| Problem | Potential Causes | Solutions | Expected Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|

| Poor cell viability after dissociation | Over-digestion with enzymes; harsh mechanical trituration; excessive time between dissection and plating | Optimize enzyme concentration and incubation time; use fire-polished pipettes; limit total dissection time to <1 hour [4] [10] [9] | Viability >85% by trypan blue exclusion [4] |

| High contamination with non-neuronal cells | Incomplete meninges removal; suboptimal embryonic age; serum-containing media | Carefully remove meninges under dissection microscope; use E16-E18 embryos; employ serum-free culture media [4] [10] [9] | >90% neuronal purity (by NeuN/MAP2 staining) [4] |

| Poor attachment to culture substrate | Inadequate coating; insufficient washing of coating solution; improper substrate concentration | Ensure complete coverage with poly-D-lysine (50μg/mL); thoroughly rinse before plating; validate coating quality [7] [10] | Uniform neuronal attachment within 24 hours [10] |

| Limited process outgrowth | Suboptimal plating density; improper culture medium; insufficient time for maturation | Plate at 1,000-5,000 cells/mm²; use Neurobasal/B-27 supplemented medium; allow 7-14 days for maturation [4] [10] | Extensive axonal/dendritic branching by DIV7-10 [4] [5] |

| High batch-to-batch variability | Different dissection practitioners; inconsistent tissue processing; animal strain differences | Standardize protocols across users; pool tissue from multiple embryos; use consistent animal suppliers [1] [4] | <15% variation in yield and purity between preparations [4] |

Experimental Protocol: Optimized Primary Neuron Culture from Embryonic Rat Hippocampus

This standardized protocol, adapted from published methodologies with proven reproducibility, addresses common yield challenges [4] [9]:

Materials Preparation

- Coating Solution: Poly-D-lysine (50μg/mL in sterile PBS) [7] [4]

- Dissection Medium: HBSS with 1mM sodium pyruvate and 10mM HEPES (pH 7.2) [4]

- Enzymatic Solution: Papain (0.5mg/mL) with DNase I (10μg/mL) in PBS containing DL-cysteine HCl, BSA, and glucose [4]

- Culture Medium: Neurobasal Plus Medium supplemented with B-27 Plus, GlutaMAX, and penicillin-streptomycin [4] [9]

Step-by-Step Procedure

Coating Culture Vessels: Coat culture surfaces with poly-D-lysine solution (50μL/cm²) for 1 hour at room temperature. Remove solution and rinse thoroughly with sterile water. Air dry uncovered in laminar flow cabinet for 2 hours [7] [4].

Tissue Dissection: Sacrifice E17-E18 pregnant rat according to institutional guidelines. Isolate embryos and decapitate into ice-cold dissection medium. Under stereomicroscope, carefully remove meninges and isolate hippocampal tissue. Transfer to pre-warmed enzymatic solution [4] [9].

Tissue Dissociation: Incubate tissue in enzymatic solution for 10 minutes at 37°C. Remove enzyme solution and add trituration medium containing DNase I. Triturate gently 10 times with fire-polished glass pipette. Allow large debris to settle for 2-3 minutes [4].

Cell Plating and Maintenance: Plate cells at desired density (1,000-5,000 cells/mm²) in complete culture medium. After 4 hours, carefully replace half the medium to remove debris. Thereafter, replace 50% of medium every 3 days [4] [10].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents for Successful Primary Neuronal Culture

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Primary Neuronal Culture

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Function | Technical Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dissociation Enzymes | Papain; Trypsin-EDTA; Collagenase | Digest extracellular matrix to create single-cell suspension | Papain is gentler than trypsin; include DNase I (10μg/mL) to prevent clumping [4] [9] |

| Culture Media | Neurobasal Plus; DMEM/F12 | Provide nutritional support for neuronal survival and growth | Serum-free media essential to prevent glial overgrowth; supplement with B-27 [4] [9] |

| Media Supplements | B-27 Supplement; CultureOne; N-2 Supplement | Provide essential growth factors and hormones | B-27 supports long-term neuronal survival; CultureOne controls astrocyte expansion [4] [5] |

| Adhesion Substrates | Poly-D-lysine; Poly-L-lysine; Laminin; Fibronectin | Promote neuronal attachment to culture surfaces | Poly-D-lysine (50μg/mL) most common; ensure complete coverage and thorough rinsing [7] [10] |

| Characterization Antibodies | Anti-MAP2; Anti-NeuN; Anti-β-III Tubulin; Anti-GFAP | Identify neuronal populations and assess purity | MAP2 for dendrites; Tau for axons; NeuN for neuronal nuclei; GFAP for astrocytes [4] [10] |

Advanced Considerations for Experimental Design

Addressing Batch-to-Batch Variability

The inherent biological variability of primary neurons, while representing a more realistic model, introduces experimental challenges. To mitigate this issue:

- Pool tissue from multiple embryos (typically 3-5) for each preparation to average individual differences [4]

- Include internal controls in each experiment to normalize between preparations

- Comprehensive characterization of each batch using neuronal markers (MAP2, NeuN) to document purity and maturity [1] [4]

Species Selection Considerations

The choice of species should align with research goals:

- Human primary neurons: Highest translational relevance but limited availability and ethical constraints [1]

- Rodent models: Well-established protocols, genetic manipulability, and availability of transgenic lines [4] [9]

- Avian models: Specific advantages for certain research areas, such as Alzheimer's studies due to APP homology [7]

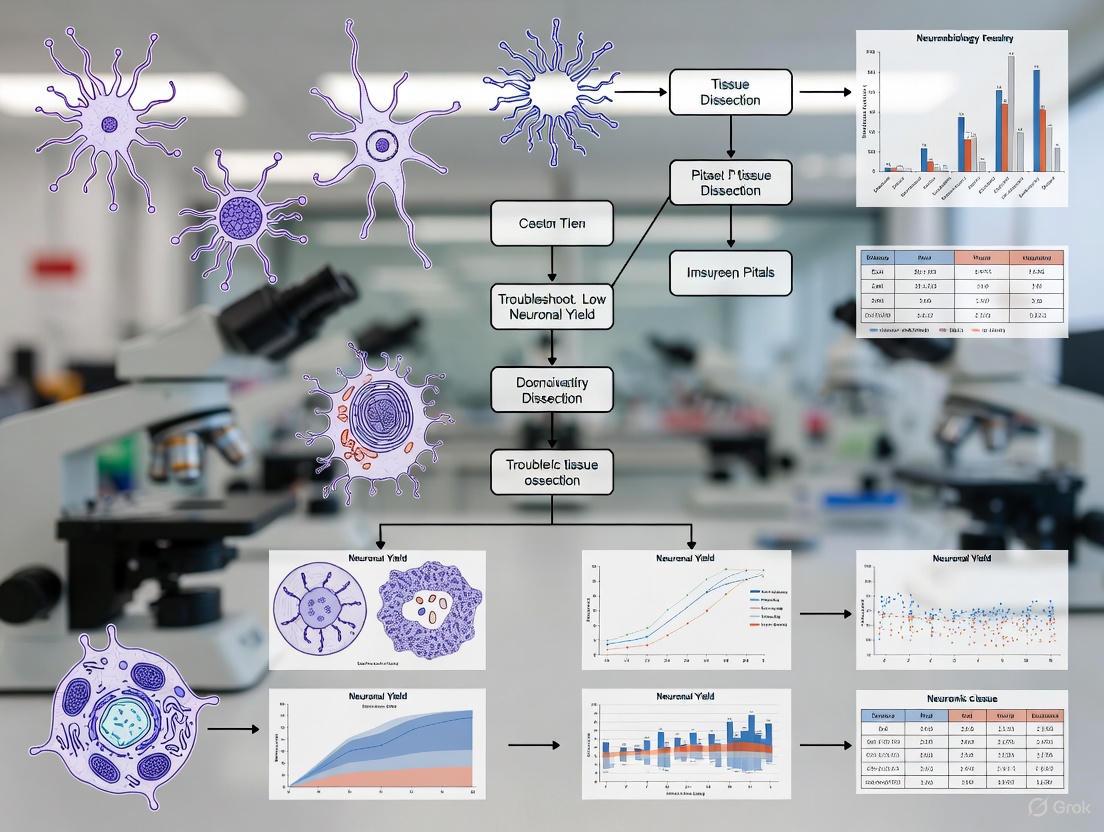

Workflow Diagram for Primary Neuron Culture

Primary neurons offer undeniable advantages for neuroscience research, particularly when investigating complex neuronal functions, disease mechanisms, and therapeutic interventions. While their culture requires specialized technical expertise and presents challenges in scalability, their physiological relevance and predictive validity make them indispensable for translational research. By implementing the optimized protocols and troubleshooting guidance presented here, researchers can significantly improve neuronal yield and culture consistency, thereby enhancing the reliability and impact of their experimental outcomes.

Troubleshooting Guides

Why is my neuronal viability low after dissection?

Low viability often results from issues during the dissection and tissue dissociation process. Key factors to check are listed in the table below.

| Potential Cause | Specific Issue | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Dissection Technique | Tissue damage, excessive stretching, or nicking of the spinal cord. [11] | Use two pairs of Dumont #5 forceps; practice precise micro-dissection to preserve tissue integrity. [11] [12] |

| Enzymatic Digestion | Over- or under-digestion with proteases like trypsin. [12] | Precisely time the enzymatic digestion. Include a brief DNase I digestion step post-trypsinization to aid in creating a single-cell suspension and improve consistency. [11] [12] |

| Cell Handling | Cells sticking to pipettes during trituration. [11] | Fire-polish Pasteur pipettes and pre-coat them with media containing serum before trituration to prevent cell adhesion. [11] |

| Plating Surface | Poor or inconsistent coating of culture vessels. [12] | Ensure consistent coating with poly-D-lysine or poly-L-lysine. For imaging, use German Desag glass #1.5 coverslips for optimal growth. [11] [13] [12] |

How can I improve the survival of low-density neuronal cultures?

Ultra-low density neurons are difficult to maintain due to a lack of paracrine support. Traditional methods use glial feeder layers, but this can confound neuron-specific studies. [13] A simplified, defined method is summarized below.

| Challenge | Traditional Glia Co-culture | Neuron-Neuron Co-culture Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Trophic Support | Relies on factors secreted by cortical astrocytes. [13] | Uses a feeder layer of high-density hippocampal neurons to provide essential trophic support. [13] |

| Experimental Confounding | Glial factors impact neuron development, complicating cell-autonomous studies. [13] | Creates a defined, serum-free system without glia, allowing for the study of neuron-specific mechanisms. [13] |

| Technical Complexity | Time-consuming and laborious to prepare glial feeder layers in advance. [13] | Simplified protocol: plate high-density and low-density neurons on the same day; flip low-density coverslips onto high-density wells after 2 hours. [13] |

| Physical Separation | Uses paraffin wax dots to create a space between glia and neuron coverslips. [13] | Etch the plastic well bottom with an 18G needle to create parallel grooves that support the coverslip, ensuring a consistent 150-200 μm space for medium exchange. [13] |

How can I minimize batch-to-batch variability in my neuronal cultures?

Consistency is critical for reproducible experiments. Variability can arise from the biological source, dissection technique, and culture components.

| Source of Variability | Impact on Culture | Corrective Action |

|---|---|---|

| Developmental Stage | Different embryonic stages yield different types and purities of neurons. [12] | Fix the developmental stage for dissection (e.g., E13 for rat commissural neurons, E16.5-E17.5 for mouse hippocampal neurons). [11] [13] [12] |

| Dissection Skill | Inconsistent dissection timing and precision. [12] | Practice micro-dissection to improve speed and precision. Use a good dissection scope and fine-point tweezers. [12] |

| Culture Components | Lot-to-lot differences in serum, growth factors, and supplements. [12] | Lot-test critical components like B27 supplement. Make fresh media and avoid antibiotics in long-term growth medium. [12] |

| Plating Density | Seeding variability affects neuronal health and glial contamination. [12] | Use an automated cell dispenser or multi-channel pipette with frequent mixing in a reservoir to ensure well-to-well consistency. [12] |

| Cell Line Purity (iPSC) | Inefficient neural induction leads to impure neuronal populations. [14] [15] [16] | Use dual SMAD inhibition for highly pure (>90%) central nervous system-type neural progenitor cells. Characterize NPCs with markers like PAX6, SOX1, and Nestin before differentiation. [16] |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

What is the best way to achieve a pure commissural neuron culture?

A highly pure (>90%) culture of embryonic rat commissural neurons can be achieved through precise micro-dissection. [11] The key is to isolate specific dorsal strips from the E13 rat spinal cord. The purity of the culture can be assessed post-plating by immunolabeling with commissural neuron markers such as DCC, LH2, and TAG1. [11]

My neurons are clumping after plating. What should I do?

Neuron clumping can be caused by the type of glass or coating on the plates. [12] To resolve this:

- Use acid-washed German Desag glass coverslips for imaging. [11] [12]

- Ensure plates are coated with a uniform layer of poly-D-lysine or poly-L-lysine. [11] [13] [17]

- During dissociation, perform the trituration steps in Ca²⁺/Mg²⁺-free HBSS to minimize cell adhesion. [11]

How can I establish a quality control (QC) assay for my cultured neurons?

Implement a functional QC assay that is easy to perform and aligns with your experimental endpoint. A calcium-influx assay is a widely used option. [12] Perform this assay repeatedly to establish baseline quality parameters and pass/fail criteria. This practice will minimize variability and increase confidence in your data. [12]

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

| Reagent / Material | Function in Neuronal Culture |

|---|---|

| Poly-D-Lysine (PDL) / Poly-L-Lysine (PLL) | Coats glass or plastic surfaces to provide a positively charged substrate that enhances neuronal adhesion. [11] [13] [17] |

| Laminin | An extracellular matrix protein often used in combination with PDL/PLL to further improve neurite outgrowth and neuronal health. [14] [17] |

| Neurobasal Medium | A serum-free medium formulation designed to support the long-term survival of primary neurons while minimizing the growth of glial cells. [11] [12] |

| B27 Supplement | A defined serum-free supplement used with Neurobasal Medium to provide hormones, antioxidants, and other necessary components for neuronal health. [11] [17] [12] |

| Dispase I / Trypsin | Enzymes used for the gentle dissociation of embryonic tissues to create single-cell suspensions while preserving cell viability. [11] [18] |

| ROCK Inhibitor (Y-27632) | A small molecule that improves the survival of neural progenitor cells (NPCs) and neurons after passaging or thawing from cryopreservation. [16] |

| STEMdiff Neural Induction Medium | A commercial serum-free medium for the efficient induction of human pluripotent stem cells into neural progenitor cells, often used with SMADi supplements. [16] |

Experimental Workflow for Consistent Neuronal Culture

The following diagram outlines the critical steps for establishing a consistent and healthy neuronal culture, from dissection to maintenance.

Figure 1. A sequential workflow for reliable neuronal culture, highlighting critical control points (yellow) to ensure consistency and health from tissue isolation to mature cells.

Co-culture Setup for Ultra-Low Density Neurons

This diagram illustrates the optimized method for cultivating ultra-low density neurons using a neuron-neuron co-culture system, which eliminates the need for a glial feeder layer.

Figure 2. Neuron-neuron co-culture setup. Etched grooves create a consistent space for a trophic factor-rich microenvironment, enabling long-term survival of ultra-low density neurons.

Essential Markers for Confirming Neuronal Identity and Purity (e.g., MAP-2)

Confirming neuronal identity and purity is a critical step in neuroscience research, particularly when troubleshooting issues like low neuronal yield from embryonic tissue dissection. The use of specific molecular markers allows researchers to verify that their cell populations are indeed neuronal and to assess the culture's purity by identifying non-neuronal contaminants. This guide provides a detailed overview of essential neuronal markers, with a focus on Microtubule-Associated Protein 2 (MAP2), and addresses common experimental challenges through targeted troubleshooting FAQs.

Key Markers for Neuronal Identification

A variety of protein markers are available to identify neurons at different developmental stages and to distinguish them from non-neuronal cells. The table below summarizes the most commonly used markers for confirming neuronal identity and assessing culture purity.

Table 1: Essential Markers for Neuronal Identification and Purity Assessment

| Marker Name | Localization | Primary Function | Specificity | Key Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MAP2 [19] | Somatodendritic compartment [20] | Microtubule stabilization, dendritic structure maintenance [20] | Mature neurons [19] | Labels dendrites and cell body; key for mature neuron confirmation |

| NeuN [19] | Nucleus | RNA-binding protein | Post-mitotic neurons [19] | Nuclear staining for quick neuronal identification and counting |

| Neurofilament Proteins (NF-M, NF-H) [19] | Cytoplasm, axons | Structural intermediate filaments in neurons [19] | Neurons (especially axons) | Identifies neuronal cytoskeleton; axonal localization |

| Synaptophysin [19] | Synaptic vesicles | Synaptic vesicle protein regulating endocytosis [19] | Presynaptic terminals | Synaptic marker for functionality assessment |

| PSD95 [19] | Postsynaptic density | Scaffolding protein maintaining synaptic homeostasis [19] | Postsynaptic terminals | Postsynaptic marker for mature connections |

| Enolase 2 (NSE) [19] | Cytoplasm | Glycolytic enzyme | Neuronal lineage [19] | Marker for neuronal commitment and maturation |

| GFAP [21] | Cytoplasm | Intermediate filament protein | Astrocytes [21] | Detects astrocyte contamination |

| IBA-1/TMEM119 [21] | Microglial cell membrane | Immune defense functions | Microglia [21] | Identifies microglial contamination |

| MBP [21] | Myelin sheaths | Myelin structural component | Oligodendrocytes [21] | Detects oligodendrocyte contamination |

Deep Dive: MAP2 as a Essential Neuronal Marker

What is MAP2?

Microtubule-Associated Protein 2 (MAP2) is a neuron-specific cytoskeletal protein that serves as a robust somatodendritic marker [20]. It belongs to the family of microtubule-associated proteins and is primarily localized to the dendrites and cell bodies of neurons [22]. MAP2 exists in multiple isoforms generated through alternative splicing, including the high molecular weight forms MAP2A and MAP2B, and the low molecular weight forms MAP2C and MAP2D [20] [22].

Why is MAP2 Ideal for Confirming Neuronal Identity?

MAP2 is particularly valuable for neuronal identification due to several key characteristics:

- High Neuron Specificity: MAP2 is expressed predominantly in neurons, making it an excellent indicator of neuronal identity [19] [22].

- Somatodendritic Localization: Unlike axonal markers, MAP2 specifically labels dendrites and cell bodies, providing clear morphological information about neuronal structure [20].

- Functional Importance in Maturation: MAP2 plays critical roles in dendritic development and stabilization, making it a marker for more mature, differentiated neurons [19].

- Stability: As a structural protein, MAP2 provides strong, consistent staining patterns that are easily quantifiable.

Table 2: MAP2 Isoforms and Their Characteristics

| Isoform | Molecular Weight | Expression Pattern | Functional Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| MAP2A | ~280 kDa [23] | Mature neurons | High molecular weight (HMW) form |

| MAP2B | ~280 kDa [23] | Both developing and adult neurons | Canonical, constitutively expressed HMW form |

| MAP2C | ~70 kDa [23] | Juvenile/developing neurons [24] | Low molecular weight (LMW) form; can be detected in axons [20] |

| MAP2D | ~70 kDa | Some glia and specific neuronal populations [20] | LMW form with additional MT-binding repeat |

The following diagram illustrates the domain structure of major MAP2 isoforms and their relationship to the similar protein Tau:

Troubleshooting Low Neuronal Yield: FAQs

How can I improve neuronal viability during dissection?

Problem: Low cell survival after embryonic tissue dissection.

Solutions:

- Minimize Processing Time: Limit dissection time per embryo to 2-3 minutes, with total dissection time not exceeding 1 hour to maintain neuronal health [9].

- Temperature Control: Keep solutions ice-cold and use pre-chilled dishes throughout the dissection process [9] [25].

- Gentle Meninges Removal: Carefully remove meninges without damaging the underlying brain tissue, as incomplete removal reduces neuron-specific purity [9] [25].

- Enzymatic Digestion Optimization: For postnatal tissue (P1-P2), use enzymatic digestion with 20 U/mL Papain and 100 U/mL DNase I in EBSS, warmed to 37°C for 10 minutes before use [25].

Why is my MAP2 staining weak or inconsistent?

Problem: Poor MAP2 immunostaining results despite confirmed neuronal presence.

Solutions:

- Check Neuronal Maturity: MAP2 expression increases with neuronal maturation. Ensure cultures have adequate time to mature (typically 7-14 days in vitro) [19].

- Fixation Conditions: Optimize fixation protocols. Methanol fixation for 5 minutes is effective for MAP2 staining [23].

- Antibody Validation: Verify antibody specificity and optimal dilution. MAP2 antibodies should produce strong somatodendritic staining [19].

- Cellular Health Assessment: Weak MAP2 staining may indicate unhealthy neurons. Check for apoptosis markers and overall culture conditions.

How can I accurately assess neuronal purity in my cultures?

Problem: Difficulty determining the percentage of true neurons in mixed cultures.

Solutions:

- Combine Multiple Markers: Use MAP2 for mature neurons with other neuronal markers (NeuN, βIII-tubulin) for comprehensive assessment [21] [19].

- Include Negative Selection Markers: Use cell type-specific surface markers and magnetic bead separation to deplete non-neuronal cells before plating [1].

- Quantitative Analysis: Use flow cytometry for MAP2-positive cells or automated imaging systems for precise quantification of neuronal vs. non-neuronal cells [23].

- Cell Type-Specific Contamination Tests: Include markers for common contaminants: GFAP for astrocytes, IBA-1/TMEM119 for microglia, and MBP for oligodendrocytes [21].

What substrate preparations optimize neuronal attachment and growth?

Problem: Poor neuronal attachment and neurite outgrowth after plating.

Solutions:

- Sequential Coating: Use poly-D-lysine (50 µg/mL) for 1 hour at 37°C, followed by laminin (10 µg/mL) overnight at 2-8°C [25].

- Proper Plating Density: Plate at appropriate densities: ~50,000 cells/cm² for high-density cultures, ~25,000 cells/cm² for lower densities [25].

- Media Formulation: Use Neurobasal medium supplemented with B-27, GlutaMAX, and appropriate growth factors [9] [25].

- Gradual Media Changes: For sensitive cultures, replace only half the media every 3-4 days to maintain nutrient and factor levels while minimizing disturbance [25].

Experimental Workflow for Neuronal Isolation and Validation

The following diagram outlines a comprehensive workflow for successful neuronal isolation, culture, and identity verification:

Research Reagent Solutions

The table below outlines essential reagents and materials needed for successful neuronal culture and identification experiments.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Neuronal Culture and Identification

| Reagent Type | Specific Examples | Function/Application | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Coating Reagents | Poly-D-Lysine [25], Laminin [25] | Provides adhesive substrate for neuronal attachment | Sequential application optimal |

| Culture Media | Neurobasal Medium [9], N21-MAX Supplement [25] | Supports neuronal survival and growth | B-27 supplement enhances viability |

| Dissociation Enzymes | Papain [25], DNase I [25] | Tissue digestion for cell isolation | Essential for postnatal tissue |

| Neuronal Markers | Anti-MAP2 [19], Anti-NeuN [19] | Neuronal identification and purity assessment | Somatodendritic vs. nuclear localization |

| Glial Markers | Anti-GFAP [21], Anti-IBA1 [1], Anti-MBP [21] | Detection of non-neuronal contamination | Critical for purity assessment |

| Growth Factors | BDNF [25], IGF-I [25], NGF [9] | Enhances neuronal survival and maturation | Concentration-dependent effects |

| Dissection Solutions | HBSS [9], EBSS [25] | Ionic balance during tissue processing | Must be ice-cold for optimal viability |

Successful confirmation of neuronal identity and purity requires a multifaceted approach combining optimized dissection protocols, appropriate marker selection, and rigorous validation methods. MAP2 stands out as an essential marker for mature neuronal identification due to its neuron-specific expression and somatodendritic localization. By implementing the troubleshooting strategies outlined in this guide—including optimized dissection timing, proper substrate preparation, and comprehensive marker panels—researchers can significantly improve neuronal yield and culture purity. Regular assessment using both positive neuronal markers (MAP2, NeuN) and negative glial markers (GFAP, IBA-1) provides the most accurate evaluation of culture composition, ensuring reliable results in neuronal research and drug development applications.

Obtaining a high neuronal yield from embryonic tissue dissection is a critical step in neuroscience research, drug discovery, and cell therapy development. The success of this process is highly dependent on several key donor factors: the developmental age of the embryo, the species from which tissue is derived, and the specific brain region being targeted. Variations in these factors directly impact cell viability, proliferation capacity, and differentiation potential, ultimately determining the quantity and quality of neurons available for downstream applications. This technical support center provides targeted troubleshooting guides and FAQs to help researchers systematically address the challenge of low neuronal yield by optimizing their approach to these fundamental donor characteristics. Understanding how these variables influence experimental outcomes enables scientists to design more robust protocols and achieve greater consistency in their neuronal culture systems.

Troubleshooting Guides: Addressing Low Neuronal Yield

Guide 1: Optimizing Tissue Dissociation Based on Donor Age

The developmental age of embryonic tissue significantly influences cellular composition, extracellular matrix density, and susceptibility to mechanical and enzymatic stress during dissociation. These factors must be carefully balanced to maximize viable cell yield.

Table 1: Troubleshooting Low Yield by Developmental Stage

| Problem Scenario | Possible Cause | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Low viability from early-stage tissue ( | High sensitivity to enzymatic digestion; fragile cells. | Reduce trypsin concentration by 50%; shorten incubation time; use DNAse to prevent clumping. |

| Poor dissociation of late-stage tissue (>E18 in mice) | Increased ECM and myelin; tougher tissue. | Optimize enzyme cocktail (e.g., papain-based); increase digestion time slightly; mechanical trituration with fire-polished pipettes. |

| Excessive cell death across all ages | Over-trituration; toxic byproducts from enzymatic reaction. | Triturate gently (<10-15 times); use Hibernate-E or other protective recovery medium during process. |

| Low attachment efficiency | Insufficient matrix coating; aged tissue has lower adhesion. | Ensure proper coating (e.g., PDL/Laminin); plate cells at higher density for late-stage cultures. |

Guide 2: Accounting for Species-Specific Differences

Protocols cannot be universally applied across species. Genetic, anatomical, and physiological differences necessitate specific adjustments to standard procedures to achieve optimal results.

Table 2: Species-Specific Optimization Parameters

| Species | Key Consideration | Adjustment for Optimal Yield |

|---|---|---|

| Mouse/Rat | Well-established developmental timelines; relatively consistent tissue hardness. | Follow standard protocols but adjust dissection timing precisely to gestational day for target neuronal subtype. |

| Human | Limited tissue availability; often post-mortem delays; larger brain size. | Prioritize shorter post-mortem intervals (<24h); account for larger gyrencephalic anatomy during dissection. |

| Non-Human Primate | Complex ethics & sourcing; close human homology but not identical. | Expect longer neurogenesis periods; adjust medium composition for species-specific growth factors. |

Guide 3: Brain Region-Specific Dissection and Culture

Different brain regions contain unique neuronal subtypes with varying metabolic requirements, adhesion properties, and growth factor dependencies. A one-size-fits-all approach will result in suboptimal yields from specific regions.

Table 3: Brain Region-Specific Challenges and Solutions

| Brain Region | Common Yield Challenge | Targeted Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Hippocampus | Contamination with adjacent cortical tissue; neuronal vulnerability. | Use finer dissection tools under high magnification; include neuroprotective agents (e.g., B-27 Supplement). |

| Cortex | Heterogeneous cell population; mixed neuronal subtypes. | Use density gradient centrifugation for preliminary purification; consider immunopanning for specific neuronal populations. |

| Striatum | High proportion of non-neuronal cells. | Use mitotic inhibitors (e.g., Cytosine β-D-arabinofuranoside) to suppress glial overgrowth after plating. |

| Cerebellum | Dense, compact tissue; difficult dissociation. | Use longer papain incubation with gentle agitation; careful mechanical disruption. |

| Ventral Mesencephalon (for dopaminergic neurons) | Small tissue size; sensitive neuronal population. | Minimize dissection time; use specialized medium with specific trophic factors (e.g., GDNF, SHH). |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: My neuronal viability is low after plating, and I see extensive cellular debris. What is the primary cause? Low viability post-plating is frequently caused by issues during the tissue dissociation phase. The most common culprits are overly aggressive mechanical trituration or the use of an inappropriate enzyme concentration and incubation time. Primary neurons are extremely fragile upon recovery from tissue dissociation. We recommend using pre-warmed complete growth medium, gentle trituration with wide-bore pipette tips, and ensuring the correct seeding density. Furthermore, for primary neurons, avoid centrifuging the cells after dissociation as they are extremely fragile [26].

Q2: How does the developmental age of the donor impact the types of neurons I can obtain? The developmental age is the primary determinant of the neuronal subtypes present and their proliferative capacity. Neural stem cells (NSCs) in the developing brain progress through distinct fate transitions, generating different neuronal lineages over time. For example, early neuroepithelial stages are enriched for genes associated with deep-layer cortical neurons and brain patterning, while later passages of NSCs become more neuro- and gliogenic, producing upper-layer neurons and glial cells [27]. Therefore, to target a specific neuronal subtype, you must harvest tissue from the precise developmental window when those neurons are being born or are post-mitotic but not fully mature.

Q3: Why are my neurons not maturing properly or forming functional networks in culture? Proper maturation requires not just adequate nutrients but also the correct combination of trophic support and culture environment. First, check that you are using the correct, fresh B-27 Supplement, as the supplemented medium is stable for only two weeks at 4°C. Second, confirm that your coating matrix (e.g., PDL/Laminin) is appropriate and has not dried out before plating, as this severely impacts attachment and neurite outgrowth. Third, neuronal network formation often requires a critical density of healthy neurons. Re-evaluate your initial seeding density and ensure you are not using a lot that has a lower-than-expected cell count [26].

Q4: My cultures are becoming overrun with glial cells after a few days. How can I suppress this? Glial overgrowth, primarily from astrocytes and oligodendrocyte precursor cells, is a common issue in mixed cortical cultures, especially from later gestational ages. The most effective strategy is to use mitotic inhibitors like cytosine arabinoside (Ara-C) or 5-fluorodeoxyuridine (FdU) after the neurons have had a chance to attach (typically 24-48 hours post-plating). This approach selectively kills dividing glial cells while leaving post-mitotic neurons unaffected. Using defined, serum-free media like Neurobasal medium supplemented with B-27 also helps to selectively support neuronal health over glial proliferation.

Q5: Are there specific considerations for transducing or transfecting neurons from different donor species? Yes, primary neurons are notoriously difficult to transduce. The main way to improve transduction is to use a higher number of viral particles per cell. For primary neurons, transduction is often more successful if performed at the time of plating rather than on established cultures. There can also be a slower onset of expression in neurons, with peak expression often occurring on day 2–3 rather than 16 hours after transduction, as seen in cell lines [28]. The sensitivity of primary cells also means it is critical to contact technical support to choose the best transfection reagent, as standard reagents can be toxic [26].

Key Signaling Pathways Governing Neuronal Development

The successful generation of neurons from dissected tissue relies on recapitulating the native developmental environment, which is orchestrated by key morphogen signaling pathways. These pathways, including Sonic Hedgehog (SHH), Wnt, BMP, and FGF, create concentration gradients that pattern the neural tube and determine neuronal identity [29].

Figure 1: Key Morphogen Pathways in Neural Patterning. Morphogens secreted from organizing centers establish neuronal identity. SHH ventralizes the neural tube, while BMPs and Wnts promote dorsal fates. Anterior-posterior patterning is controlled by antagonism between Wnt/FGF (caudalizing) and their inhibitors (rostralizing) [29].

Experimental Workflow for Maximizing Neuronal Yield

A successful neuronal culture experiment requires careful planning and execution at every stage, from donor selection to final plating. The following workflow diagram outlines the critical steps and key decision points.

Figure 2: Neuronal Culture Workflow. This optimized workflow integrates donor factor considerations at each critical step to maximize final neuronal yield and health. Key parameters must be adjusted based on species, age, and brain region [26] [27] [30].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 4: Key Reagents for Successful Neuronal Culture

| Reagent Category | Specific Product Examples | Function & Importance |

|---|---|---|

| Basal Media | Neurobasal, DMEM/F-12 | Provides essential nutrients and salts; Neurobasal is optimized for postnatal neuronal health. |

| Serum-Free Supplements | B-27 Supplement, StemPro Neural Supplement | Crucial for long-term neuronal survival and function; provides hormones, antioxidants, and pro-survival factors. B-27 supplemented medium is stable for only 2 weeks at 4°C [26] [31]. |

| Enzymes for Dissociation | Papain, Trypsin-EDTA, Accutase | Breaks down extracellular matrix to create single-cell suspension; papain is generally gentler on sensitive neurons. |

| Coating Substrates | Poly-D-Lysine (PDL), Laminin, Geltrex | Provides a adhesive surface for neuronal attachment and neurite outgrowth. Required for proper adherence when using animal origin-free supplements [26]. |

| Growth Factors | BDNF, GDNF, FGF2, EGF | Guides neuronal maturation, subtype specification, and supports neural stem cell expansion. FGF2 dose and timing critically regulate NSC fate transitions [27]. |

| Neuroprotective Agents | ROCK Inhibitor (Y-27632), Antioxidants | Increases cell survival after dissociation and during freezing/thawing; ROCK inhibitor prevents apoptosis in dissociating cells. |

| Mitotic Inhibitors | Cytosine β-D-arabinofuranoside (Ara-C) | Suppresses glial cell proliferation in mixed cultures, allowing neurons to thrive. |

Step-by-Step Optimized Protocols for High-Yield Neuron Isolation

Customized Dissection Techniques for Cortex, Hippocampus, and Hindbrain

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What are the most common causes of low neuronal yield during embryonic brain dissection? Low neuronal yield is most frequently caused by excessive mechanical stress during tissue dissociation (over-trituration) and enzymatic over-digestion [5]. An incomplete removal of the meninges and blood vessels can also trap neural tissue, while deviations from the optimal embryonic day (E) for dissection can target a developmental stage with insufficient neurons or excessive gliogenesis [5].

Q2: How can I improve the viability of sensitive neuronal populations, like those from the hindbrain? Using fire-polished glass Pasteur pipettes with customized tip diameters (e.g., reduced to ~675 µm) for gentle trituration is crucial [5]. Furthermore, maintaining strict control over enzymatic digestion times and temperatures, and using defined, serum-free culture media supplemented with growth factors like B-27, can significantly enhance neuronal survival and inhibit excessive glial cell expansion [5].

Q3: My cultured neurons are overrun by glial cells. How can I prevent this? The primary strategy is to use a chemically defined, serum-free culture system. The addition of supplements like CultureOne is explicitly recommended to control astrocyte expansion without harming neuronal health [5]. Preparing cultures from the correct embryonic age is also critical, as older fetuses have a higher proportion of glial precursors.

Q4: Are there specific anatomical landmarks for consistently isolating the embryonic hindbrain? Yes, the hindbrain is isolated by first removing the cortex, cerebellum, and cervical spinal cord remnants. The separation from the midbrain is made by cutting from the dorsal fold that separates the two regions down towards the ventral pontine flexure [5]. Careful removal of the meninges is a final, essential step.

Troubleshooting Guide: Low Neuronal Yield

| Problem | Potential Cause | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Low Cell Viability | Enzymatic over-digestion; Excessive mechanical trituration | Standardize trypsin incubation time (15 min at 37°C); Use fire-polished glass pipettes, limit trituration to 10 passes per step [5] |

| High Glial Contamination | Serum in culture medium; Incorrect embryonic day | Use serum-free medium (e.g., Neurobasal Plus); Add CultureOne supplement; For hindbrain, use E17.5 mouse fetuses [5] |

| Inconsistent Tissue Isolation | Unclear anatomical landmarks; Incomplete meninges removal | Identify key landmarks: dorsal fold & ventral pontine flexure; Remove meninges under dissecting microscope [5] |

| Poor Neuronal Differentiation | Suboptimal culture medium; Inadequate coating of culture surfaces | Use defined neuronal medium (e.g., NB27 complete with B-27 Plus and GlutaMax); Ensure surfaces are properly coated with poly-D-lysine/laminin [5] |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol for Mouse Fetal Hindbrain Dissociation and Culture

This optimized protocol is designed for the reliable culture of hindbrain neurons, a region critical for vital functions like breathing and heart rate control [5].

Animals and Tissue Dissection:

- Use time-mated pregnant mice. The presence of a vaginal plug defines embryonic day (E) 0.5 [5].

- At E17.5, euthanize the pregnant mouse by cervical dislocation and decapitate the fetuses [5].

- Extract the whole brain and place it in sterile PBS. Under a dissecting microscope, isolate the brainstem by removing the cortex, cerebellum, and remnants of the cervical spinal cord.

- Separate the hindbrain from the midbrain by cutting from the dorsal fold between the regions down to the ventral pontine flexure.

- Carefully remove the meninges and blood vessels. Pool up to four hindbrains per tube [5].

Tissue Dissociation:

- Transfer the hindbrains to a 15 mL tube containing 4 mL of HBSS without Ca²⁺/Mg²⁺ (Solution 1) [5].

- Mechanically dissociate gently with a plastic pipette into 2–3 mm³ pieces.

- Add 350 µL of 0.5% Trypsin and 0.2% EDTA per tube. Incubate for 15 minutes at 37°C [5].

- Loosen the tissue matrix with 10 gentle passes using a long-stem glass Pasteur pipette.

- Incubate for another 5 minutes at 37°C.

- Triturate 10 times with a fire-polished glass Pasteur pipette (tip diameter reduced to ~675 µm) [5].

- Add 4 mL of HBSS with Ca²⁺/Mg²⁺ (Solution 2) to stop the digestion. Let the tube sit for 2–3 minutes to allow large debris to settle.

- Carefully transfer the cell suspension to a new tube, leaving the debris behind.

Cell Plating and Culture:

- Centrifuge the cell suspension and resuspend the pellet in the pre-warmed NB27 complete medium (Neurobasal Plus Medium supplemented with B-27 Plus, L-glutamine, and penicillin-streptomycin) [5].

- Plate the cells on culture vessels pre-coated with poly-D-lysine/laminin.

- On the third day in vitro, add CultureOne supplement to the medium to a 1x concentration to control astrocyte expansion [5].

General Guide for Rodent Brain Extraction and Dissection

This method prioritizes brain integrity without perfusion, suitable for regional dissection [32].

Brain Extraction:

- Euthanize the rodent humanely and decapitate.

- Make a midline incision on the scalp and retract the skin.

- Use scissors or a drill to carefully open the skull along the suture lines.

- Gently lift the brain from the cranial cavity, starting from the anterior end and severing the cranial nerves and optic chiasm. Let the brain slide out into a petri dish with ice-cold dissection buffer [32].

Regional Dissection (Cortex, Hippocampus, etc.):

- Place the brain in a brain matrix or stabilize it on a chilled surface.

- Using a sharp blade, make coronal sections at the desired levels.

- For the hippocampus, identify its distinctive C-shaped structure in the medial temporal lobe of the section and micro-dissect it out.

- For the cerebral cortex, carefully peel away the grey matter from the underlying white matter and subcortical structures.

- For other regions like the striatum and thalamus, use anatomical landmarks in the coronal sections to guide their isolation [32].

Experimental Workflow Visualization

The following diagram outlines the key stages of the embryonic hindbrain dissection and culture protocol, highlighting critical steps that impact neuronal yield.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

| Reagent / Kit | Function in the Protocol |

|---|---|

| Neurobasal Plus Medium | A defined, serum-free basal medium optimized for the growth and long-term viability of primary neurons [5]. |

| B-27 Plus Supplement | A serum-free formulation containing antioxidants, hormones, and proteins that support neuronal health and reduce glial contamination [5]. |

| CultureOne Supplement | A chemically defined supplement used to control the expansion of astrocytes in mixed neural cultures without affecting neurons [5]. |

| Trypsin/EDTA (0.5%) | A proteolytic enzyme solution used to loosen the extracellular matrix for tissue dissociation. Concentration and time must be carefully controlled [5]. |

| Fire-Polished Glass Pipettes | Glass Pasteur pipettes whose tips have been heated and smoothed to create a smaller, uniform opening, minimizing shear stress on delicate neurons during trituration [5]. |

Low neuronal yield from embryonic tissue dissection is a significant bottleneck in neuroscience research, affecting experiment reproducibility and data quality. The enzymatic digestion process is a critical point where failures often occur. This guide provides targeted troubleshooting strategies to optimize enzyme selection, concentration, and timing to maximize viability and yield of primary neurons.

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Low Cell Viability After Digestion

| Potential Cause | Diagnostic Steps | Corrective Action |

|---|---|---|

| Over-digestion | Check for excessive cell fragmentation under microscope; measure trypan blue exclusion. | Shorten digestion time (e.g., reduce by 5-min increments); pre-warm enzyme solution to avoid cold shock. |

| Enzyme Concentration Too High | Review enzyme lot-specific activity; use the lowest effective concentration in a test series. | Titrate enzyme concentration; for trypsin, common range is 0.05%-0.25% [1]. |

| Incorrect Enzyme Type | Analyze tissue composition (connective tissue content); consult literature for specific brain regions. | Switch enzyme type: Trypsin for general use; consider papain for sensitive neurons [1]. |

| Inadequate Enzyme Inactivation | Verify FBS concentration in wash medium; ensure complete removal of enzyme solution. | Increase FBS concentration (e.g., 10%) in wash medium; add an additional centrifugation wash step. |

Problem: Incomplete Tissue Dissociation

| Potential Cause | Diagnostic Steps | Corrective Action |

|---|---|---|

| Under-digestion | Observe large tissue clogs in strainer; count large cell aggregates in suspension. | Gradually extend digestion time; incubate at 37°C with gentle agitation to improve penetration. |

| Enzyme Activity Loss | Check enzyme storage conditions and expiration date; pre-test on a small tissue sample. | Use fresh enzyme aliquots; avoid repeated freeze-thaw cycles; confirm water bath temperature is stable. |

| Inadequate Mechanical Disruption | Visually inspect tissue pieces pre- and post-trituration. | Optimize trituration: Use fire-polished Pasteur pipettes of decreasing bore sizes; avoid air bubbles. |

| Incorrect pH or Buffer | Calibrate pH meter; confirm compatibility of buffer with enzyme (e.g., Ca²⁺ for some enzymes). | Use recommended buffer (e.g., HBSS); maintain optimal pH (typically 7.2-7.4 for trypsin) [1]. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is the single most critical factor to optimize for neuronal yield?

A1: While all parameters are interdependent, digestion time is often the most volatile variable. Even a few minutes can drastically impact viability. Begin with published protocols as a baseline (e.g., 15-20 min for trypsin on embryonic rodent cortex [1]) and perform a time-course experiment, holding enzyme concentration constant, to find the narrow window between complete dissociation and cell death.

Q2: How does the age or developmental stage of the embryonic tissue affect digestion?

A2: The age of the embryo is paramount. Younger tissue (e.g., E14-E16 in mice) has less extracellular matrix and connective tissue, requiring milder digestion (shorter time, lower enzyme concentration). Older embryonic tissue or postnatal tissue has a more robust matrix, often needing longer digestion or different enzyme blends. Always tailor the protocol to the precise developmental stage [1].

Q3: Can I combine different enzymes, and what are the risks?

A3: Yes, using enzyme blends (e.g., trypsin with DNase) can be highly effective. Proteases like trypsin break down proteins, while DNase degrades DNA released from damaged cells, reducing viscosity and clumping. The primary risk is synergistic toxicity, leading to rapid loss of viability. When blending, reduce the concentration of each component by 25-50% initially and monitor viability closely [1] [33].

Q4: Our yields are high but our neurons fail to mature or develop incorrectly in culture. Could the digestion process be the cause?

A4: Absolutely. Overly harsh digestion can damage surface receptors and proteins critical for signaling and adhesion. This sub-lethal damage may not kill the cell immediately but can impair axon outgrowth, synaptogenesis, and overall maturation. If this occurs, shift focus from maximizing yield to optimizing health by gentler digestion and more rigorous enzymatic inactivation [1].

The following table consolidates key parameters from established protocols to serve as a starting point for optimization.

Table 1: Enzymatic Digestion Parameters for Neural Tissue

| Parameter | Typical Range | Example Application | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Trypsin Concentration | 0.05% - 0.25% | General dissociation of embryonic rodent brain [1] | Higher concentrations risk damaging surface antigens. |

| Digestion Temperature | 37°C | Standard for most enzymatic reactions [1] | Essential for maintaining optimal enzyme activity. |

| Digestion Time | 5 - 30 minutes | Embryonic mouse cortex; highly tissue-dependent [1] | Must be determined empirically for each tissue batch. |

| Enzyme Inactivation | 5-10% FBS | Quenching trypsin activity post-digestion [1] | Critical step to halt proteolytic damage. |

Experimental Workflow for Protocol Optimization

The following diagram outlines a systematic workflow for troubleshooting and optimizing your enzymatic digestion protocol to improve neuronal yield.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 2: Key Reagents for Primary Neuronal Isolation

| Reagent | Function | Specific Example |

|---|---|---|

| Proteolytic Enzymes | Digests extracellular matrix and intercellular proteins to dissociate tissue. | Trypsin [1], Papain [1] |

| Enzyme Inactivator | Stops enzymatic activity to prevent continued proteolysis and cell damage. | Fetal Bovine Serum (FBS) [1] |

| Cell Strainer | Removes undissociated tissue clumps and debris to obtain a single-cell suspension. | 70 µm nylon mesh [1] |

| Density Gradient Medium | Purifies specific cell types based on density; separates live cells from debris. | Percoll [1] |

| Antibody-Conjugated Beads | Isolates highly pure cell populations via immunocapture (e.g., microglia, astrocytes). | Anti-ACSA-2 or Anti-CD11b magnetic beads [1] |

| Basal Salt Solution | Provides an isotonic, buffered environment during dissection and digestion. | Hanks' Balanced Salt Solution (HBSS) [1] |

This technical support guide addresses the common challenge of low neuronal yield following the mechanical trituration of dissected embryonic tissue. The practices below are designed to help you maximize cell viability and optimize your experimental outcomes.

Core Concepts and Quantitative Data

What is Mechanical Trituration?

Mechanical trituration is the process of repeatedly passing dissociated tissue through a pipette of narrowing bore size to break down tissue fragments into a suspension of single cells. This is a critical step following enzymatic digestion, and its execution directly impacts final cell viability, yield, and health [34] [9].

The table below summarizes key parameters and their measurable effects on cell isolation outcomes, as established in the literature.

| Parameter | Target / Optimal Practice | Impact on Viability & Yield | Supporting Evidence |

|---|---|---|---|

| Trituration Tool | Fire-polished Pasteur pipette [34] | Prevents excessive shear stress that can lyse cells; maintains cell integrity. | Protocol for hippocampal neurons [34] |

| Number of Passes | ~7 passes with standard pipette; ~5 passes with fire-polished pipette [34] | Balances thorough tissue dissociation with minimal mechanical damage to cells. | Protocol for hippocampal neurons [34] |

| Tissue Dissociation Method | Bacillus licheniformis protease over collagenase [35] | Superior for maintaining cell integrity; conventional collagenase treatment compromises cell viability. | EV isolation from zebrafish [35] |

| Mechanical-Only Workflow | Semi-automated, enzyme-free dissociation (TissueGrinder) [36] | Successfully isolates cells with 75% success rate for outgrowth; induces slight cell stress but not apoptosis. | Processing of tumor tissues [36] |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Standard Trituration for Primary Hippocampal Neurons

This protocol is adapted from established methods for isolating and culturing primary mouse hippocampal neurons [34].

- Post-Digestion Washing: After enzymatic digestion (e.g., with trypsin), allow the tissue pieces to settle at the bottom of a 15 mL conical tube. Carefully remove the supernatant and wash the tissue pellet with 5 mL of warm HBSS (37°C). Let the tissue settle completely and repeat this wash step a total of three times [34].

- Resuspension: After the final wash, remove the supernatant and add 2 mL of fresh, sterile HBSS to the tissue pellet [34].

- Initial Trituration: Using a standard sterile 9-inch Pasteur pipette, gently triturate the tissue by drawing it up and down approximately 7 times. At this stage, some larger tissue pieces are normal. Allow these large pieces to settle to the bottom of the tube [34].

- Transfer Supernatant: Transfer the supernatant, which now contains a portion of the dissociated cells, to a fresh sterile 50 mL conical tube [34].

- Fine Trituration: To the remaining tissue pieces, add another 2 mL of HBSS. Using a fire-polished Pasteur pipette (with an opening diameter of approximately 0.5 mm), triturate the tissue gently another 5 times [34].

- Combine Suspensions: Allow any remaining large pieces to settle, and then combine this supernatant with the supernatant collected in step 4 [34].

- Cell Counting and Plating: Count the cells using a hemocytometer. As a general rule, subtract 20% from the final count to account for cell death that may occur after plating. Plate the cells at the recommended density (e.g., 6 x 10^4 cells/well in a 24-well plate) in the appropriate plating medium [34].

Protocol 2: Advanced Workflow for Sensitive Tissues

For tissues or applications where enzymatic digestion must be minimized, an optimized mechanical and enzymatic workflow has been shown to preserve cell integrity effectively [35].

- Tissue Preparation: Begin with finely minced tissue pieces.

- Enzymatic Digestion: Incubate tissue with a superior enzyme alternative, Bacillus licheniformis protease, at 4°C for 25 minutes under slow agitation. Perform trituration with a 1000 μL pipette tip (10 times up/down) every 5 minutes during the incubation [35].

- Reaction Stop: Add EDTA to a final concentration of 10 mM to stop the enzyme reaction once larger cell clumps have dissociated [35].

- Filtration and Purification: Pass the resulting cell mixture through a 40 μm cell strainer. Centrifuge the filtrate at 300 g for 10 minutes at 4°C. The resulting pellet can be further purified using a Percoll gradient centrifugation step to isolate viable cells [35].

- Viability Assessment: Resuspend the final cell pellet in an appropriate ice-cold medium and evaluate viability using a method like flow cytometry with DRAQ7 staining [35].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: My cell viability after trituration is consistently low. What are the most likely causes? The most common causes are overly aggressive trituration and using pipette tips with an incorrect bore size. Ensure you are using a fire-polished Pasteur pipette to create a smooth, rounded opening that reduces shear forces. Additionally, avoid excessive trituration passes; follow a two-step process with a defined number of passes for each pipette type [34]. Finally, review your enzymatic digestion step, as over-digestion can make cells more fragile during subsequent mechanical trituration.

Q2: How can I reduce contamination from non-neuronal cells in my primary cultures? The choice of dissection technique and culture medium are critical. When dissecting, take extreme care to remove the meninges completely, as they are a primary source of contaminating cells [9]. Furthermore, using a serum-free culture medium like Neurobasal medium supplemented with B-27 is well-established to support neuronal growth while inhibiting the proliferation of non-neuronal cells like astrocytes [34].

Q3: I am working with a new tissue type. How can I optimize the trituration process? It is highly recommended to perform a systematic comparison of dissociation techniques. A recent study successfully compared mechanical homogenization, collagenase treatment, and Bacillus licheniformis protease digestion, identifying the latter as superior for preserving cell integrity in their model [35]. You can use a similar approach, using cell viability and yield as your key metrics for success. For complex or fibrous tissues, exploring a semi-automated, enzyme-free mechanical dissociator like the TissueGrinder may also be beneficial [36].

Q4: Why is my cell yield low even though the tissue seems fully dissociated? This can occur if the mechanical trituration is too harsh. While the tissue may break down, excessive force can lyse cells, leading to a high count of non-viable cells that are not reflected in a live-cell count. Always perform a viability count (e.g., with Trypan Blue) in addition to a total cell count. Furthermore, ensure that your initial tissue dissection is performed quickly and kept on ice to maintain cell health before dissociation begins [9].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Materials

The table below lists key reagents and materials used in the protocols cited above.

| Reagent / Material | Function / Application | Example from Protocol |

|---|---|---|

| Fire-polished Pasteur Pipette | Gently dissociates tissue fragments into single cells with minimal shear stress. | Used for fine trituration of hippocampal tissue [34]. |

| Bacillus licheniformis Protease | An enzymatic alternative to collagenase for tissue digestion; better preserves cell surface proteins and viability. | Used for gentle enzymatic digestion of zebrafish larval heads [35]. |

| Hanks' Balanced Salt Solution (HBSS) | A balanced salt solution used for washing tissue and as a buffer during dissociation. | Used for washing minced hippocampal tissue and during trituration steps [34]. |

| Neurobasal Medium / B-27 Supplement | A serum-free culture medium designed to support the growth and maintenance of primary neurons. | Used as the base for feeding media for cortical, hippocampal, and spinal cord neurons [9]. |

| Poly-D-Lysine / Collagen | Coating substrates for culture plates; provide a surface that promotes neuronal attachment and growth. | Used to coat cultureware for primary hippocampal neurons [34]. |

Experimental Workflow and Decision-Making

The following diagram illustrates the core procedural workflow for mechanical trituration and the key decision points for troubleshooting.

Trituration Workflow and Troubleshooting

The diagram below maps the relationship between key experimental variables, the challenges they create, and the recommended solutions to preserve cell viability.

Cause and Effect in Trituration Challenges

Troubleshooting Guide: Low Neuronal Yield from Embryonic Tissue

This guide addresses the common challenges researchers face when achieving low yield and viability during the isolation and culture of primary neurons from embryonic tissue. Use the following tables and FAQs to diagnose and resolve issues in your experimental workflow.

Troubleshooting Table: Primary Neuronal Culture Issues

| Problem Area | Specific Issue | Potential Cause | Recommended Solution | Key References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tissue Dissection & Dissociation | Low cell viability post-dissociation | Over-digestion with proteolytic enzymes (e.g., trypsin); excessive mechanical trituration. | Optimize enzyme concentration and incubation time. [5] Use fire-polished Pasteur pipettes with reduced diameter for gentler trituration. [5] Incorporate enzyme inhibitors (e.g., soybean trypsin inhibitor) post-digestion. [37] | [5] [9] [37] |

| Low overall cell yield | Incomplete tissue dissection; failure to fully remove protective meninges. | Improve dissection skill to ensure complete isolation of target brain region (e.g., hippocampus, cortex, hindbrain). [9] Carefully remove all meninges to prevent fibroblast contamination and physical barriers to dissociation. [9] | [9] [5] | |

| Substrate Coating | Poor cell attachment | Incorrect coating concentration or protein; inadequate incubation. | Optimize coating density (e.g., 0.61 μg/cm² for common ECM proteins). [38] Select appropriate substrate: Poly-D-Lysine/Laminin for general neurons, [9] Vitronectin for specific differentiation. [38] Ensure proper, sterile preparation and washing of coated surfaces. [38] | [38] [9] |

| Unwanted differentiation | Use of substrate that promotes differentiation over maintenance. | Avoid fibronectin and collagen for pluripotent stem cell cultures; use laminin or vitronectin instead. [38] | [38] | |

| Medium Formulation | Poor long-term survival & maturation | Lack of essential supplements; use of serum which promotes glial growth. | Use serum-free, chemically-defined media (e.g., Neurobasal). [5] [9] Supplement with B-27 or CultureOne for crucial trophic factors and to control glial expansion. [5] [9] | [5] [9] [37] |

| Batch-to-batch variability | Use of fetal bovine serum (FBS) with undefined components. | Transition to chemically-defined (CD) media formulations. [37] If adapting cells from serum, use a gradual adaptation (GA) protocol to minimize stress. [37] | [37] [1] | |

| Environmental Control | Cellular stress & death | Incorrect pH and CO₂ levels; temperature fluctuations. | Maintain strict control of incubator at 37°C, 5% CO₂. [1] Use HEPES-buffered solutions during dissection outside the incubator. [5] | [1] [5] |

| Contamination | Microbial (e.g., bacterial, fungal) contamination. | Implement strict aseptic technique. Use antibiotics (e.g., Penicillin-Streptomycin) in dissection and initial plating media. [5] | [5] |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: My neurons are not attaching well to the culture plate after seeding. What are the most critical factors to check?

A1: Poor attachment is most frequently linked to the substrate coating. First, verify the concentration and integrity of your coating proteins (e.g., Poly-D-Lysine, Laminin). Using a consistent and optimized density, such as 0.61 μg/cm², is crucial. [38] Second, ensure the coating solution is prepared and applied correctly, with an overnight incubation at 37°C and proper washing with sterile PBS before plating to remove any non-adsorbed material. [38] Finally, confirm that the coating protein is appropriate for your cell type, as different neurons and stem cells have specific substrate preferences. [38]

Q2: How can I reduce the overgrowth of astrocytes and other glial cells in my primary neuronal cultures?

A2: Controlling glial proliferation is essential for maintaining neuronal purity. Two primary strategies are highly effective:

- Use Chemically-Defined, Serum-Free Medium: Serum (e.g., FBS) contains factors that promote glial cell division. Switching to a serum-free medium like Neurobasal, supplemented with B-27, is fundamental. [9] [5]

- Incorporate Mitotic Inhibitors: Add defined supplements like CultureOne to your medium a few days after plating (e.g., at the third day in vitro). This supplement contains components that inhibit the division of non-neuronal cells without harming post-mitotic neurons. [5]

Q3: I am transitioning from serum-containing to chemically-defined (CD) medium, but my cells are dying. How can I improve this process?

A3: An abrupt switch can cause cellular stress. Implement a Gradual Adaptation (GA) protocol. [37] Start by culturing your cells in a mixture of your original serum-containing medium and the new CD medium (e.g., a 1:1 ratio). Every 48 hours or at each passage, incrementally increase the proportion of CD medium (e.g., to 75%, then 100%). During this process, using a supportive attachment substrate like fibronectin can significantly improve cell viability and attachment. [37]

Q4: Why is there so much variability in my neuronal yields between different isolation sessions?

A4: Batch-to-batch variation is a recognized challenge in primary cell isolations. [1] Key factors to standardize include:

- Precise Embryonic Age: The developmental stage of the embryo critically impacts neuronal yield and viability. Adhere strictly to the recommended embryonic day (e.g., E17-E18 for rat cortex, E17.5 for mouse hindbrain). [9] [5]

- Dissection Speed and Skill: Limit the total dissection time to under one hour to maintain tissue health. [9] Practice consistent technique to minimize damage and ensure complete tissue collection.

- Enzyme Digestion Consistency: Carefully control the concentration, volume, and incubation time of dissociation enzymes like trypsin across all batches. [5] [9]

Experimental Workflow and Logic

The following diagram illustrates the critical decision points and steps in a primary neuron culture protocol, highlighting where the troubleshooting guidance above applies.

Research Reagent Solutions

This table details key reagents and their critical functions in establishing successful primary neuronal cultures.

| Reagent / Material | Function & Application | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Poly-D-Lysine & Laminin | Synthetic and natural proteins used to coat culture surfaces to promote neuronal attachment and neurite outgrowth. | Optimal combined use; coating concentration (e.g., 0.61 μg/cm²) and incubation time are critical for performance. [38] [9] |

| Neurobasal Medium | A serum-free, chemically-defined basal medium optimized for the long-term survival of hippocampal and other CNS neurons. | Must be supplemented for full efficacy; minimizes glial cell growth compared to serum-containing media. [5] [9] |

| B-27 Supplement | A serum-free supplement designed to support the growth and maintenance of primary CNS neurons. Provides hormones, antioxidants, and other essential nutrients. | A key component for neuronal health in serum-free conditions; used in protocols for cortex, hippocampus, and spinal cord cultures. [9] |

| CultureOne Supplement | A chemically-defined, serum-free supplement used to suppress the growth of contaminating cells (e.g., fibroblasts, glia) in primary neuronal cultures. | Typically added a few days after plating (e.g., Day 3 in vitro) to control glial proliferation without harming post-mitotic neurons. [5] |

| Trypsin/EDTA | Proteolytic enzyme solution used for the enzymatic digestion of the extracellular matrix in dissected tissue to create a single-cell suspension. | Concentration and incubation time must be tightly optimized to avoid damaging cells; activity is often halted with inhibitors or serum. [5] [37] |

Troubleshooting Low Yield: From Dissection to Culture

Common Pitfalls in Tissue Dissection and Meninges Removal

For researchers isolating primary neurons from embryonic tissue, the dissection process and subsequent removal of the meninges are critical steps that directly impact neuronal yield and viability. Incomplete meninges removal is a major source of contamination, while improper dissection technique can mechanically damage delicate neuronal tissue. This guide addresses common challenges and provides proven solutions to optimize these technically demanding procedures.

Frequently Asked Questions

Q1: Why is complete meninges removal so critical for successful neuronal culture?

Complete meningeal removal is essential for achieving high-purity neuronal cultures. The meninges are protective membranes composed of multiple connective tissue layers (dura, arachnoid, and pia mater) that surround the brain [39]. If not thoroughly removed, these tissues become a significant source of non-neuronal cell contamination, primarily fibroblasts, which can rapidly proliferate and outcompete neurons in culture [1] [9]. This overgrowth alters the culture environment and depletes nutrients, ultimately reducing neuronal viability and yield. Furthermore, the meninges contain arachnoid granulations and blood vessels that introduce additional cell types, further compromising the homogeneity of your culture [39] [40].

Q2: What are the most common signs of incomplete meninges removal?

The most straightforward indicator of incomplete meninges removal is the rapid emergence of proliferative, spindle-shaped fibroblast-like cells in your culture within the first few days. These cells are morphologically distinct from the phase-bright, rounded somas of healthy neurons [9]. During the dissection itself, visual cues can alert you to potential problems. The meninges often appear as thin, translucent, but relatively tough membranes that can be challenging to distinguish from the underlying neural tissue, especially in embryonic specimens. If you notice yourself pulling away strands of tissue that seem fibrous or if the brain surface appears ragged after removal attempts, these suggest the meninges are not being cleanly separated [9].

Q3: My neuronal yields are consistently low after dissection. What might I be doing wrong?

Low neuronal yield can stem from several points in the dissection workflow. The table below summarizes common pitfalls and their impacts.

Table 1: Common Pitfalls Leading to Low Neuronal Yield

| Pitfall | Consequence | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Prolonged dissection time | Increased cell death due to ambient temperature and pH shift. | Limit dissection to 2-3 minutes per embryo [9]. |

| Over-aggressive mechanical trituration | Physical shearing and rupture of neuronal cell bodies. | Use polished glass pipettes with progressively smaller bore sizes; avoid excessive force [9]. |

| Incomplete or overly harsh enzymatic digestion | Low cell yield or damage to surface proteins and receptors. | Optimize enzyme concentration (e.g., Trypsin, Dispase) and duration; always use a stopper [1] [18]. |

| Incorrect developmental stage of source tissue | Immature or post-mitotic neurons not optimally viable. | Use age-matched embryos (e.g., E17-18 for rat cortex) [9]. |

Q4: How can I improve my technique for removing meninges from embryonic brain tissue?

Successful meninges removal requires patience, practice, and the right tools. The key is to work under high-quality magnification in a dish filled with cold dissection buffer to maintain tissue health. Use two pairs of fine #5 forceps [9]. Anchor the brain tissue gently with one forceps, and use the other to grasp any visible edge of the meningeal membrane. The goal is to peel the meninges away in sheets rather than picking at them, which would tear the underlying brain parenchyma. For embryonic tissue, some protocols suggest that careful mechanical dissociation alone can suffice if the meninges are completely removed, circumventing the need for enzymatic digestion that can damage cell surface proteins [1] [9].

Troubleshooting Guide

Table 2: Troubleshooting Common Dissection and Meninges Removal Problems

| Problem | Possible Causes | Recommended Solutions |

|---|---|---|

| High fibroblast contamination | Incomplete meninges removal. | Practice dissection technique on non-valuable tissue; use fine forceps under high magnification [9]. |