Precision Gene Delivery for Neural Circuit Manipulation: Strategies, Tools, and Clinical Frontiers

This article provides a comprehensive overview of the cutting-edge gene delivery strategies revolutionizing neural circuit manipulation for researchers and drug development professionals.

Precision Gene Delivery for Neural Circuit Manipulation: Strategies, Tools, and Clinical Frontiers

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of the cutting-edge gene delivery strategies revolutionizing neural circuit manipulation for researchers and drug development professionals. It covers the foundational principles of viral vectors, notably adeno-associated viruses (AAVs), and their axonal transport properties. The scope extends to methodological applications, including serotype and promoter selection for cell-type-specific targeting, the integration of CRISPR tools for functional genomics, and advanced delivery techniques. It further addresses critical troubleshooting and optimization challenges such as immune responses and off-target effects, and concludes with rigorous validation and comparative analysis of emerging technologies. This resource synthesizes the current state of the field, offering a practical guide for designing precise neural circuit interventions with strong therapeutic potential.

The Blueprint of Brain Access: Viral Vectors and Circuit Tracing Fundamentals

Adeno-associated virus (AAV) has emerged as the predominant viral vector for in vivo gene delivery to the nervous system, revolutionizing approaches for neural circuit manipulation and the treatment of neurological disorders. Its ascendancy stems from a unique combination of favorable biological properties: non-pathogenicity, low immunogenicity, and the ability to mediate long-term transgene expression in post-mitotic neurons [1] [2]. The fundamental structure of AAV is elegantly simple—a protein capsid approximately 25 nm in diameter protecting a single-stranded DNA genome of ~4.7 kilobases—yet its application is powerfully versatile [3] [1]. For neuroscience research, AAV provides a precision toolset for delivering sensors, actuators, and modulators to defined neural populations, enabling unprecedented dissection of circuit function and therapeutic intervention. This article details the anatomical features of AAV that make it indispensable for neural gene delivery, providing application notes and protocols tailored for research and drug development professionals working in neuroscience.

Anatomical Deconstruction of the AAV Vector

The AAV Genome: ITRs and Transgene Cassette

The recombinant AAV (rAAV) genome is a masterwork of minimalistic design, wherein all viral coding sequences are replaced by the therapeutic or experimental transgene expression cassette, flanked by the essential Inverted Terminal Repeat (ITR) sequences [3] [1]. These 145-base-pair ITRs are the only viral cis-elements retained in rAAV vectors and serve as critical functional components [4]. They function as origins of replication, primers for second-strand synthesis, and signals for genome packaging into the capsid [1] [4]. The ITRs form highly stable, GC-rich hairpin structures that are notoriously challenging for standard molecular biology workflows, as they are prone to recombination and mutation during plasmid propagation in bacteria, necessitating specialized sequencing and cloning strategies for validation [4].

The transgene cassette, housed between the ITRs, typically consists of a promoter, the cDNA of interest, and a polyadenylation signal [1]. For neural applications, promoter selection is paramount for targeting specific cell types. Constitutive promoters like CAG (a hybrid of CMV early enhancer and chicken β-actin) provide strong, ubiquitous expression, while cell-type-specific promoters (e.g., Synapsin for neurons, GFAP for astrocytes, CaMKIIa for excitatory neurons) enable precise targeting within heterogeneous brain tissues [1]. The total size of the expression cassette must not exceed ~4.5–4.7 kb, a constraint that requires careful optimization of all regulatory elements [5].

The AAV Capsid: Serotypes and Tropism

The AAV capsid, an icosahedral shell assembled from 60 copies of VP1, VP2, and VP3 proteins in an approximate 1:1:10 ratio, is the primary interface with the host organism and the main determinant of tissue tropism and immunogenicity [3] [1]. The variable regions on the capsid surface mediate interactions with cell-surface receptors, dictating the vector's binding, internalization, and transduction efficiency in different tissues [6] [2].

Diverse naturally occurring AAV serotypes exhibit distinct neural tropisms, enabling researchers to select a vector optimized for their experimental needs. AAV9 and AAVrh.10 are particularly notable for their ability to cross the blood-brain barrier (BBB) following systemic administration, enabling non-invasive brain transduction [6] [2]. AAV2 is a well-characterized serotype with a broad tropism but is often used with other serotypes through "pseudotyping" (packaging an AAV2 genome into a different serotype's capsid) to combine the robust ITR function of AAV2 with the enhanced neural transduction of other capsids [1]. AAV5 exhibits high transduction efficiency for neurons in specific brain regions, such as the cortex and striatum, due to its use of sialic acid as a primary receptor [6] [1].

Table 1: AAV Serotypes and Their Neural Applications

| Serotype | Primary Receptors | Neural Tropism & Key Characteristics | Example Neural Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| AAV1 | Sialic acid [6] | High transduction in muscle and CNS [2] | Intraparenchymal delivery to specific brain regions |

| AAV2 | HSPG [6] | Broad CNS tropism; well-characterized [1] [2] | Preclinical models of Parkinson's disease [6] |

| AAV5 | Sialic acid, PDGFR [6] | Efficient transduction of cortical and striatal neurons [1] | Neural circuit mapping in cortex and striatum |

| AAV8 | Laminin Receptor [6] | Strong liver and muscle tropism; moderate CNS [6] [2] | Comparative studies with other serotypes |

| AAV9 | Terminal N-linked galactose [6] | Robust BBB penetration; widespread CNS transduction after systemic delivery [6] [2] | Treatment of spinal muscular atrophy (SMA) with Zolgensma [2] |

| AAV-DJ | Hybrid | Engineered for high transduction in multiple cell types [2] | When a single, high-potency vector is needed for screening |

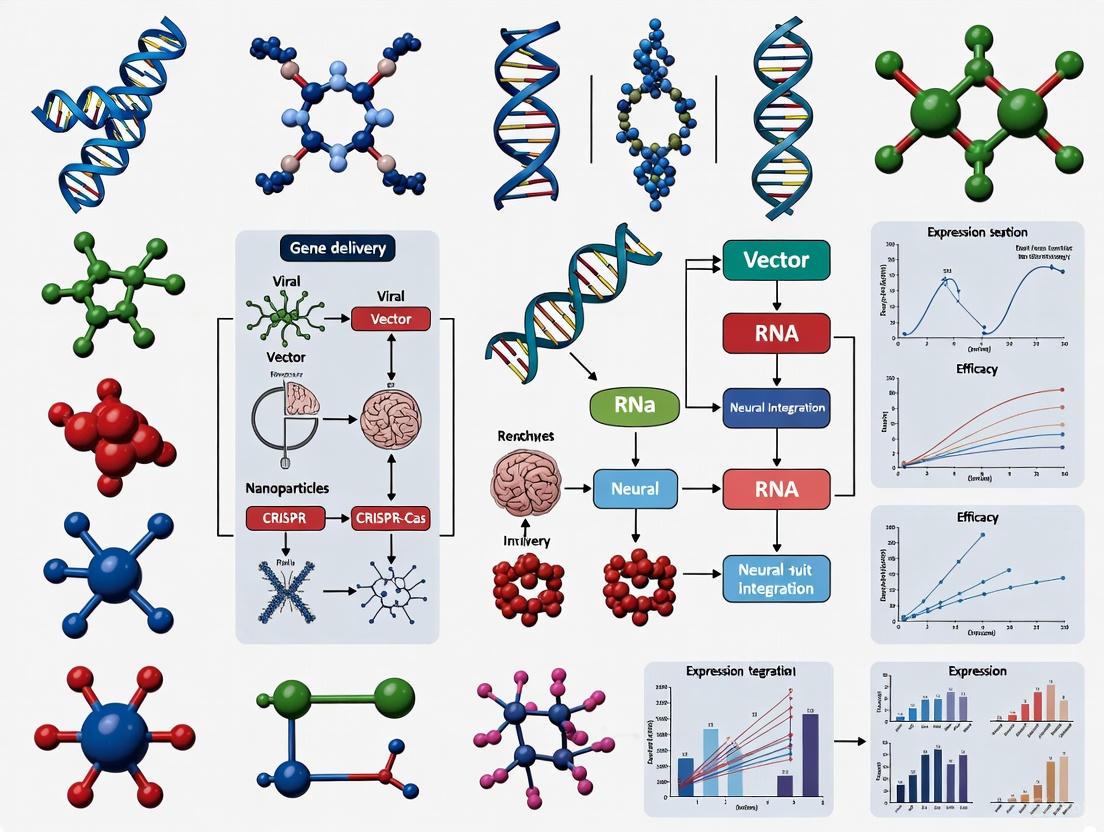

The following diagram illustrates the journey of an AAV vector from cellular entry to transgene expression, a critical process for neuroscientists to understand for optimizing experimental outcomes.

Advanced AAV Engineering for Neuroscience

Overcoming the Packaging Limit: Dual AAV Strategies

The strict ~4.7 kb packaging constraint is a significant limitation for neuroscientists aiming to deliver large transgenes, such as those encoding certain Cas proteins for CRISPR editing, optogenetic tools with complex regulatory elements, or large genomic regulatory sequences. Dual AAV vector systems have been developed to circumvent this limitation, effectively doubling the deliverable payload to ~8-9 kb [5]. These systems rely on co-transduction of the same cell by two separate AAV vectors, each carrying a portion of the full transgene, which is then reconstituted inside the nucleus.

The three primary dual AAV strategies, differentiated by their reconstitution mechanism, are summarized below.

Table 2: Comparison of Dual AAV Vector Strategies

| Strategy | Reconstitution Level | Mechanism | Advantages & Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hybrid/Overlapping | DNA | Homologous recombination between overlapping regions in the two vector genomes [5] | Higher efficiency in some studies; requires careful design of homologous region [5] |

| Trans-Splicing (REVeRT) | RNA | Splice donor/splice acceptor sites facilitate ligation of two pre-mRNAs into a single mature mRNA [5] | Avoids potential issues with DNA-level recombination; efficiency depends on splicing machinery |

| Split Intein | Protein | Fusion of two protein fragments mediated by autocatalytic intein sequences [5] | Reconstitution at protein level; suitable for specific large proteins; intein activity is context-dependent |

The choice of strategy depends on the experimental goal and the nature of the transgene. For extensive genomic elements, the hybrid or trans-splicing approaches are typically used, while the split intein approach is ideal for large proteins where the split site is known and does not disrupt function.

Capsid Engineering and Promoter Selection for Specificity

Beyond leveraging natural serotypes, the field is rapidly advancing through rational capsid engineering and directed evolution to create vectors with enhanced properties for neuroscience [3]. These next-generation capsids aim to achieve:

- Enhanced CNS specificity and reduced off-target transduction.

- Higher transduction efficiency for specific neuronal subtypes (e.g., dopaminergic, GABAergic).

- Evasion of pre-existing neutralizing antibodies to broaden patient eligibility in clinical trials [7].

- Retrograde transport from projection terminals to cell bodies, enabling access to neurons based on their connectivity.

Parallel to capsid engineering, the selection of cell-specific promoters is a critical and complementary strategy for restricting transgene expression. The use of promoters such as hSyn (human synapsin) for pan-neuronal expression or CaMKIIa for excitatory neurons provides an additional layer of precision, ensuring that the delivered genetic payload is active only in the intended cellular population [1].

Essential Protocols for AAV Application in Neural Research

Protocol: Design and Production of a Dual AAV System

This protocol outlines the key steps for implementing the overlapping dual AAV strategy, which is often the most efficient for delivering large genes to the nervous system [5].

I. Design and Cloning (Duration: 4-6 weeks)

- Identify Split Site: Choose a suitable location within the large transgene to split it into two fragments (5' and 3'). The split site should be in a region tolerant to the addition of a short peptide sequence or intron, if needed.

- Design Vector Components:

- Vector A (5' half): Contains the ITR, a promoter, the 5' fragment of the transgene, and a homologous overlapping region or splice donor site.

- Vector B (3' half): Contains the ITR, a homologous overlapping region or splice acceptor site, the 3' fragment of the transgene, and a polyA signal.

- The homologous overlapping region is typically an artificial, highly recombinogenic sequence of 200-500 bp.

- Molecular Cloning: Clone the designed fragments into AAV transfer plasmids. Use bacterial strains optimized for ITR stability (e.g., Stbl2, SURE, or proprietary strains) and validate all plasmid preps with specialized ITR-sequencing to prevent mutations in these critical regions [4].

II. AAV Production and Purification (Duration: 2-3 weeks)

- Co-transfection: Co-transfect HEK293 cells with the dual AAV transfer plasmids (Vector A and Vector B), a Rep/Cap plasmid (e.g., for AAV9), and an adenoviral helper plasmid using polyethylenimine (PEI) or PEI MAX in suspension culture [3] [2].

- Harvest and Lysis: Harvest cells 48-72 hours post-transfection. Lyse cells via freeze-thaw cycles and/or detergent treatment to release viral particles.

- Purification: Purify the crude lysate using iodixanol gradient centrifugation or affinity chromatography to isolate filled capsids from empty ones and cellular debris [3].

- Quality Control (QC): Determine the genome titer (vg/mL) of each batch by qPCR. Analyze the integrity and purity of the packaged genome using next-generation sequencing (NGS) to detect potential rearrangements or contaminants [4]. Assess the full/empty capsid ratio by ELISA or analytical ultracentrifugation.

III. In Vitro Evaluation (Duration: 3-4 weeks)

- Co-transduction: Transduce relevant neural cell models (e.g., primary neurons, iPSC-derived neurons, neurospheres) with a 1:1 mixture of Vector A and Vector B. Include controls transduced with each vector alone.

- Assess Reconstitution: After 7-14 days, assess functional reconstitution:

- Microscopy: If the transgene is a fluorescent protein, directly visualize reconstituted fluorescence.

- Western Blot: Detect the full-length, reconstituted protein.

- Functional Assay: Measure the activity of the reconstituted protein (e.g., electrophysiology for ion channels, CRISPR editing efficiency for Cas9).

Protocol: Intraparenchymal Delivery of AAV in Mouse Brain

This is a standard surgical protocol for precise, localized AAV delivery, a common requirement for neural circuit manipulation.

I. Pre-Surgical Preparation (Duration: 1-2 hours)

- Vector Preparation: Thaw the AAV stock on ice and dilute to the desired working titer (e.g., 1x10^12 – 1x10^13 vg/mL) in sterile PBS. Centrifuge briefly before loading to remove aggregates. Keep on ice and protected from light.

- Animal Anesthesia: Induce anesthesia in an adult mouse (e.g., C57BL/6) using 4-5% isoflurane in an induction chamber. Maintain anesthesia at 1-2% isoflurane via a nose cone on the stereotaxic frame.

- Stereotaxic Setup: Secure the mouse in the stereotaxic instrument. Apply ophthalmic ointment to prevent corneal drying. Shave the scalp and disinfect the surgical site with alternating scrubs of betadine and 70% ethanol.

II. Surgical Procedure (Duration: 30-60 minutes per animal)

- Incision: Make a midline incision (~1.5 cm) in the scalp to expose the skull.

- Bregma Identification: Identify Bregma and Lambda landmarks. Level the skull to ensure Bregma and Lambda are in the same dorsal-ventral plane.

- Coordinate Calculation: Calculate the target coordinates relative to Bregma for your brain region of interest (e.g., Primary Motor Cortex M1: AP +1.8 mm, ML ±1.5 mm; Dorsal Striatum: AP +0.5 mm, ML ±1.8 mm, DV -2.8 mm).

- Craniotomy: Drill a small burr hole at the calculated anterior-posterior (AP) and medial-lateral (ML) coordinates.

- Viral Injection:

- Load a calibrated glass micropipette or a 33-gauge Hamilton syringe with the AAV solution.

- Lower the needle slowly to the target dorsal-ventral (DV) coordinate.

- Infuse the virus at a slow, controlled rate (e.g., 50-100 nL/minute) using a microinjection pump. A typical injection volume is 500 nL - 1 µL.

- Wait 5-10 minutes after infusion to allow for pressure dissipation before slowly retracting the needle.

III. Post-Surgical Care and Analysis

- Closure: Suture or glue the scalp incision. Administer analgesic (e.g., Carprofen) and place the animal in a clean, warm cage until fully recovered from anesthesia.

- Expression Time: Allow sufficient time for transgene expression. Robust protein expression typically peaks 2-4 weeks post-injection for most AAV serotypes and neural transgenes.

- Validation: Sacrifice the animal and analyze the brain for transgene expression and function using histology, microscopy, electrophysiology, or behavioral assays.

The workflow for this protocol, from design to analysis, is outlined below.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for AAV Neuroscience

| Reagent/Material | Function & Application | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| AAV Transfer Plasmid | Backbone for transgene cassette cloning; contains ITRs [1] [4] | Use plasmids with validated, intact ITRs [4]. Select a backbone with appropriate promoter (e.g., CAG, hSyn, CaMKIIa). |

| Rep/Cap Plasmid | Provides AAV replication (Rep) and capsid (Cap) proteins in trans during production [3] [2] | Defines the serotype (e.g., AAV9, AAV5, AAV-DJ). Pseudotyping (e.g., AAV2/9) is common. |

| Adenoviral Helper Plasmid | Provides essential helper functions from adenovirus (E4, E2a, VA) for AAV replication [3] [2] | Necessary for AAV life cycle in production cells. |

| HEK293 Cells | Production cell line; provides adenovirus E1 gene [2] | Can be used in adherent or suspension culture for scale-up. |

| PEI MAX | Transfection reagent for delivering plasmids to HEK293 cells [3] | Cost-effective and scalable compared to commercial lipid-based reagents. |

| Iodixanol | Density gradient medium for purifying AAV particles post-lysis [3] | Effectively separates full capsids from empty ones and contaminants. |

| DNase I | Enzyme used during qPCR titering to degrade unencapsidated DNA, ensuring accurate genome titer (vg/mL) [3] | Critical for quality control and determining accurate dosing. |

| Stereotaxic Instrument | Precision apparatus for targeting specific brain regions in vivo [citation:Protocol 4.2] | Must be calibrated regularly. Includes micromanipulators and injectors. |

| Glass Micropipettes / Hamilton Syringe | For delivering small volumes of AAV suspension directly into brain parenchyma [citation:Protocol 4.2] | Provides precise control over injection volume and location. |

AAV vectors represent a sophisticated and continually evolving platform for delivering genetic cargo to the nervous system. Their anatomy—from the compact ITR-flanked genome to the versatile and engineerable capsid—is perfectly suited for the demands of modern neuroscience research and therapeutic development. By understanding the principles of AAV biology, including serotype selection, capsid engineering, and strategies to overcome payload limitations, researchers can harness this powerful tool with greater precision and efficacy. The protocols and resources provided here serve as a foundation for the successful design, production, and application of AAV vectors to manipulate neural circuits, model disease, and pioneer the next generation of gene therapies for neurological disorders.

The era of genomic medicine has firmly arrived, with viral vectors standing as indispensable tools for both basic neuroscience research and the development of therapeutic interventions for neurological disorders. While adeno-associated virus (AAV) vectors have emerged as a predominant choice for in vivo neuronal transduction due to their safety profile and neuronal tropism, a comprehensive gene delivery strategy for neural circuit manipulation requires a broader arsenal [8]. AAV's limitations, particularly its constrained packaging capacity of approximately 4.7 kb, can be prohibitive for delivering larger genetic payloads or complex transcriptional regulatory elements [8] [9]. Furthermore, its predominantly episomal persistence may not support long-term transgene expression in scenarios requiring stable genomic integration, such as in tracking cell lineages or permanent genetic modifications.

This application note moves beyond AAV to provide a detailed comparison of three critical viral vector systems—Lentivirus (LV), Retrovirus (RV), and Adenovirus (AdV)—for neuroscience applications. We focus on their unique biological characteristics, which present distinct solutions to the challenges of gene therapy and neural circuit analysis [10]. Key differentiators include their genome integration capabilities, transgene expression duration, payload capacity, and cellular tropism within the complex environment of the central nervous system (CNS) [11]. By framing these vectors within the context of gene delivery strategies for neural circuit manipulation, we aim to equip researchers with the knowledge to select the optimal vector for specific experimental or therapeutic goals, from manipulating specific neuronal populations to achieving long-term genetic modification in the brain and spinal cord.

Comparative Analysis of Viral Vector Systems

Selecting the appropriate viral vector is a critical first step in designing robust and interpretable neuroscience experiments. The table below provides a systematic, quantitative comparison of the key features of Lentivirus, Retrovirus, and Adenovirus vectors, contrasting them with the familiar benchmark of AAV.

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Viral Vectors for Neuroscience Applications

| Feature | Lentivirus (LV) | Retrovirus (RV) | Adenovirus (AdV) | Adeno-associated Virus (AAV) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Genome Type | Single-stranded RNA | Single-stranded RNA | Double-stranded DNA | Single-stranded DNA |

| Packaging Capacity | ~8 kb [9] | ~8 kb [9] | Up to ~35 kb [11] [9] | ~4.7 kb [8] [9] |

| Integration Profile | Integrates into host genome (prefers active genes) [8] | Integrates into host genome (requires cell division) [11] | Non-integrating (episomal) [9] | Predominantly non-integrating (episomal) [10] [11] |

| Expression Duration | Long-term (stable integration) [12] | Long-term (stable integration) | Short- to medium-term (transient, weeks) [9] | Long-term (episomal, can persist for years) [9] |

| Tropism in CNS | Broad (neurons, glia); can be pseudotyped (e.g., VSV-G) [8] [11] | Dividing cells (e.g., progenitors, glioma cells) [11] | Broad (neurons, astrocytes, oligodendroglia, ependymal cells, microglia) [11] | Varies by serotype; neurons preferred for AAV2/5/9 [11] [13] |

| Typical Titer (functional) | ~10^8 - 10^9 IU/mL | ~10^7 - 10^8 IU/mL | ~10^10 - 10^12 VP/mL [9] | ~10^11 - 10^13 VG/mL |

| Immunogenicity | Low to Moderate | Low to Moderate | High (adjuvant properties) [11] | Very Low [8] [14] |

| Key Neuroscience Applications | Stable gene expression in neurons, ex vivo cell engineering, delivery of large or multiple transgenes [8] | Lineage tracing, targeting neural progenitors and brain tumors [11] | High-level transient expression, delivery of very large genetic payloads (e.g., CRISPR-Cas9 systems), cancer gene therapy [15] | Long-term gene expression in post-mitotic neurons, gene therapy for monogenic disorders, optogenetics/chemogenetics [8] [13] |

This comparative analysis reveals clear strategic trade-offs. Lentiviral vectors are distinguished by their ability to mediate stable genomic integration in non-dividing cells, a critical feature for long-term manipulation of mature neuronal circuits [8]. In contrast, Retroviral vectors remain the tool of choice for studies focused on dividing cell populations, such as neural stem cells or gliomas, due to their dependence on cell division for integration [11]. Adenoviral vectors excel where high levels of transient transgene expression are needed or for delivering exceptionally large genetic payloads, such as the ~10 kb CRISPR-Cas9 nuclease, though their pronounced immunogenicity must be carefully considered [11] [15].

Decision Workflow and Experimental Protocols

Vector Selection and Experimental Workflow

The following diagram outlines a systematic decision-making workflow for selecting the most appropriate viral vector based on key experimental parameters. This logical pathway helps researchers align their goals with the inherent strengths of each vector system.

Detailed Protocol: Lentiviral Transduction of Spinal Cord Neurons for Stable Gene Expression

This protocol details the methodology for direct in vivo lentiviral vector delivery to the spinal cord, a common paradigm for manipulating motor and sensory circuits, based on established procedures in rodent models [12].

Title: Lentiviral-Mediated Gene Delivery to Rat Spinal Cord

Objective: To achieve stable, long-term transgene expression in spinal cord neurons via direct parenchymal injection of lentiviral vectors.

Materials & Reagents:

- Viral Vector: Third-generation, self-inactivating (SIN) lentiviral vector, pseudo-typed with VSV-G envelope, titer ≥ 1x10^8 IU/mL [8] [14].

- Animals: Adult Sprague-Dawley rats (200-300 g).

- Anesthesia: Isoflurane vaporizer system (5% for induction, 1.5-2.5% for maintenance in O2).

- Surgical Equipment: Stereotaxic apparatus, fine-glass micropipette (30-50 μm tip) or Hamilton syringe, microinjection pump.

- Analgesia: Carprofen (4 mg/kg, s.c.) [16].

Procedure:

- Anesthesia and Prepping: Induce and maintain anesthesia with isoflurane. Secure the rat in a stereotaxic frame. Maintain body temperature at 37°C using a homeothermic blanket. Administer carprofen pre-emptively for analgesia.

- Surgical Exposure: Perform a dorsal midline incision over the vertebral column. Conduct a hemilaminectomy at the target vertebral level (e.g., L4/L5 for lumbar enlargement) to expose the spinal cord without durotomy.

- Vector Injection: Load the lentiviral preparation into the injection system. Position the glass pipette approximately 100 μm lateral to the central vein and insert it 150 μm into the spinal cord parenchyma [16]. Inject a total volume of 500 nL per site at a slow, controlled rate of 50 nL/min to minimize tissue damage and reflux [16]. Multiple injections along the rostro-caudal axis can be performed to cover a larger area.

- Post-injection Care: Wait 5-10 minutes before slowly retracting the pipette to allow for pressure equilibration. Suture the muscle and skin layers. Administer post-operative carprofen for 48-72 hours and monitor the animal until full recovery.

Validation & Analysis:

- Time Course: Transgene expression is typically assessed 2-4 weeks post-injection to allow for stable integration and protein expression [12].

- Histology: Perfuse animals transcardially with 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA). Process spinal cord tissue for cryosectioning and immunohistochemistry using antibodies against the transgene product (e.g., EGFP) and neuronal markers (e.g., NeuN) to confirm neuronal transduction and quantify efficiency.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Successful execution of viral vector-based experiments relies on a suite of specialized reagents and tools. The following table catalogues key solutions for working with lentiviral, retroviral, and adenoviral vectors.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Viral Vector Neuroscience

| Reagent / Solution | Function & Application | Example Use-Case |

|---|---|---|

| VSV-G Pseudotyped LV Particles | Expands tropism to a broad range of dividing and non-dividing cells, including neurons, by utilizing the Vesicular Stomatitis Virus Glycoprotein (VSV-G) envelope [8]. | Enables efficient transduction of primary neuronal cultures or CNS neurons in vivo for stable gene expression [8] [11]. |

| Third-Generation, SIN Lentiviral Packaging Systems | Enhances biosafety by splitting viral genes across multiple plasmids and deleting the viral promoter/enhancer to prevent replication-competent virus generation and reduce genotoxicity [14]. | Standard for clinical-grade ex vivo cell engineering (e.g., CAR-T cells) and preclinical research requiring high safety standards [8]. |

| Polybrene (Hexadimethrine Bromide) | A cationic polymer that reduces electrostatic repulsion between viral particles and the cell membrane, thereby increasing transduction efficiency in vitro. | Added to cell culture media (at 4-8 μg/mL) during viral infection to enhance retroviral or lentiviral transduction of primary glial cells or neural stem cell lines. |

| CellSTACK / HYPERStack Culture Chambers | Scale-up platforms for adherent cell culture, providing high surface area in a small footprint for large-scale viral vector production under controlled, scalable conditions [14]. | Used in upstream bioprocessing to grow the producer cells (e.g., HEK293T) needed for high-yield lentivirus or adenovirus manufacturing. |

| AI-Based Enhancer Prediction Tools | Computational tools that identify short, cell-type-specific genomic "enhancer" sequences to drive selective transgene expression, overcoming the limited packaging capacity of viral vectors [13]. | Designing compact, cell-type-specific AAV or LV expression cassettes (e.g., for targeting spinal inhibitory interneurons) without the need for large genomic promoters [16] [13]. |

The strategic selection of viral vectors is fundamental to advancing neuroscience research and therapeutic development. While AAV remains a powerful tool for many in vivo applications, a sophisticated understanding of lentiviral, retroviral, and adenoviral vector systems dramatically expands the experimental toolbox. Lentiviral vectors are unparalleled for achieving stable genetic manipulation in post-mitotic neurons, retroviral vectors provide exclusive access to dividing cellular compartments, and adenoviral vectors offer a solution for delivering very large or highly immunogenic transgenes on a transient basis.

Future developments in viral vectorology will continue to enhance the precision and safety of neural circuit manipulation. Emerging trends include the engineering of novel synthetic capsids and envelopes to refine cellular tropism, the development of integration-deficient lentiviral vectors for safer transient expression, and the increasing use of computational biology and AI to design compact, highly specific genetic regulatory elements [13]. The ongoing NIH BRAIN Initiative's "Armamentarium for Precision Brain Cell Access" project exemplifies this direction, generating a versatile set of validated gene delivery systems for targeting specific neural cell types with exceptional accuracy [13]. By leveraging the distinct advantages of each viral vector system and integrating these next-generation technologies, researchers are poised to deconstruct the complexities of neural circuits with unprecedented precision, paving the way for transformative therapies for a broad spectrum of neurological and neuropsychiatric disorders.

Recombinant adeno-associated viruses (rAAVs) have emerged as a preeminent tool for delineating the intricate connectivity of neural circuits in the mammalian brain. Their prominence in neuroscience research stems from an ideal safety profile (Biosafety Level-1), low immunogenicity, capacity for high-titer production (10¹¹–10¹⁴ viral genomes/mL), and ability to achieve stable, long-term transgene expression in the nervous system [17]. The fundamental principle underlying their application in circuit mapping is axonal transport—the natural capacity of viruses to be trafficked within neurons, either from the soma toward axon terminals (anterograde) or from axon terminals back to the soma (retrograde) [18] [17]. This application note details the mechanisms, serotype selection, and methodological protocols for employing AAVs in anterograde and retrograde neuronal tracing, framed within the broader context of gene delivery strategies for neural circuit manipulation.

Fundamental Transport Mechanisms and AAV Serotypes

Cellular Mechanisms of Axonal Transport

AAV trafficking within neurons is an active process mediated by cellular motor proteins and specific endosomal compartments. Research on AAV9, which provides insights into the general mechanisms, has demonstrated that after cellular entry, the virus is trafficked into various vesicular compartments [19] [20]. Crucially, Rab7-positive late endosomes or lysosomes containing AAV exhibit high motility [19]. The retrograde transport of these compartments (toward the cell body) is driven primarily by the motor protein cytoplasmic dynein, and this process is dependent on Rab7 function [19] [20]. Conversely, anterograde transport (away from the cell body toward synaptic terminals) is driven by kinesin-2 [19] [20]. This understanding of the underlying cellular machinery is essential for designing effective tracing strategies and interpreting experimental results.

Key AAV Serotypes and Their Transport Properties

The propensity for anterograde or retrograde transport is heavily influenced by the AAV capsid serotype, which determines the virus's tropism and interaction with host cell receptors.

Table 1: Key AAV Serotypes for Neuronal Tracing

| Serotype | Primary Transport Direction | Key Characteristics | Common Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| AAV1 | Predominantly Anterograde | Can exhibit anterograde transsynaptic transport at high titers (>10¹³ GC/ml); also shows some retrograde transport [21] [17]. | Mapping output pathways; transsynaptic labeling of postsynaptic neurons [22]. |

| AAV2 | Anterograde (Non-transsynaptic) | Wide neuronal tropism; binds heparan sulfate proteoglycan (HSPG); traditionally used for local transduction [17] [23]. | Local gene delivery to neurons within an injection site. |

| AAV9 | Bidirectional | Efficient axonal transport driven by dynein (retrograde) and kinesin-2 (anterograde) [19] [20]. | Widespread transduction in the CNS; global gene delivery. |

| AAV-retro | Efficient Retrograde | Engineered variant for high-efficiency retrograde access to projection neurons [18] [17]. | Mapping input networks; targeting neurons based on their projection targets. |

Protocols for Anterograde and Retrograde Tracing

Protocol 1: Anterograde Transsynaptic Tracing with AAV1

This protocol describes the use of high-titer AAV1 for mapping monosynaptic outputs from a defined brain region, enabling the genetic manipulation of postsynaptic neurons.

1. Viral Vector Preparation:

- Use a self-complementary AAV1 (scAAV1) vector to bypass the rate-limiting step of second-strand DNA synthesis, leading to stronger and faster transgene expression [17] [22].

- Employ a strong ubiquitous promoter, such as CAG or CBA, to drive high-level expression of the transgene, which is critical for detectable transsynaptic transfer [23] [22].

- The viral titer is critical. Ensure a high titer ≥ 1.0 × 10¹³ genome copies (GC)/mL for efficient transneuronal spread [21] [22]. Reducing the titer to 10¹¹ GC/mL can eliminate this property [17].

2. Stereotaxic Intracranial Injection:

- Anesthetize the animal (e.g., mouse) and secure it in a stereotaxic frame. Maintain anesthesia with 1.5-2% isoflurane [21].

- After exposing the skull, use calibrated coordinates to drill a small hole above the target brain region (e.g., prefrontal cortex, medial geniculate nucleus).

- Load the viral preparation into a glass micropipette with a beveled tip (inner diameter ~20 µm).

- Inject the virus via pressure injection at a slow, controlled rate (e.g., 15-30 nL/min) [21]. The total injection volume is typically 40-100 nL for mice.

- Leave the pipette in place for 5-10 minutes post-injection to minimize backflow along the injection tract [21].

3. Post-Injection and Analysis:

- Allow adequate time for viral transport and gene expression. Transsynaptic labeling can be observed within 3-6 weeks post-injection [22].

- Perfuse and fix the brain for histological processing. Analyze the injection site and putative downstream target regions for the presence of the transgene (e.g., GFP) using microscopy.

- Specificity can be confirmed by the known anatomy of the pathway (e.g., robust labeling in the contralateral, but not ipsilateral, superior colliculus after retinal injection) [22].

Protocol 2: Retrograde Tracing with AAV-retro

This protocol utilizes the engineered AAV-retro serotype for efficient retrograde access to neurons that project to the injection site.

1. Viral Vector Preparation:

- Use an AAV-retro vector packaged with a transgene of interest (e.g., Cre recombinase, fluorescent protein) [18] [17].

- While AAV-retro is highly efficient, note that not all neuronal pathways are transduced equally; some, such as certain brainstem and catecholamine pathways, may show poor transduction [18].

2. Stereotaxic Intracranial Injection:

- Follow the same stereotaxic surgery and injection procedures as in Protocol 1.

- Inject the AAV-retro vector into the target region where axon terminals of interest are located (e.g., striatum).

3. Post-Injection and Analysis:

- Allow 2-4 weeks for retrograde transport and sufficient transgene expression in the cell bodies of projecting neurons [18].

- Identify retrogradely labeled neurons in upstream brain regions that are known to project to the injection site.

- For functional manipulation, AAV-retro can deliver optogenetic tools (e.g., Channelrhodopsin), chemogenetic tools (e.g., DREADDs), or recombinases for intersectional strategies [18] [17].

Table 2: Comparison of Key Tracing Methodologies

| Parameter | Anterograde Tracing (AAV1) | Retrograde Tracing (AAV-retro) |

|---|---|---|

| Direction of Spread | Presynaptic → Postsynaptic | Postsynaptic → Presynaptic |

| Primary Application | Mapping output networks | Mapping input networks |

| Key Experimental Consideration | Requires very high titer for transsynaptic spread | Pathway-dependent transduction efficiency |

| Toxicity & Expression | Low cytotoxicity; long-term expression | Low cytotoxicity; long-term expression |

| Complexity | Can be achieved with a single vector in wild-type animals [22] | Can be combined with Cre-dependent systems for cell-type specificity |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Successful implementation of AAV tracing experiments requires a suite of reliable reagents and tools.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for AAV Tracing

| Reagent / Tool | Function / Description | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| scAAV1 Vector | Self-complementary AAV1 for efficient anterograde transsynaptic tracing [22]. | Delivering fluorescent proteins or functional effectors to postsynaptic cells. |

| AAV-retro Vector | Engineered capsid for highly efficient retrograde tracing [18]. | Labeling or manipulating neurons based on their projection targets. |

| Cre/loxP System | Enables cell-type-specific transgene expression. | Injecting AAV1-Cre into a region; Cre-dependent reporter vector or AAV-DIO effector in a Cre-driver mouse line [18]. |

| Fluorescent Reporters | (e.g., GFP, tdTomato). Visualize infected neurons and their processes. | Determining injection site spread and locating transduced cells in target regions. |

| Digital PCR (ddPCR) | Method for absolute quantification of viral genome titer without a standard curve; more robust than qPCR for in-process samples [24]. | Accurately determining the viral titer, a critical parameter for transsynaptic tracing. |

| Transmission Electron Microscopy (TEM) | Visualizes AAV capsid integrity, aggregation, and sample impurities [24]. | Quality control of viral vector preparations. |

Workflow and Pathway Visualization

The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow for designing and executing an AAV-based circuit tracing experiment, integrating the key decision points and methodologies discussed.

Figure 1: Experimental Workflow for AAV-Based Circuit Tracing. This flowchart outlines the key steps and strategic decisions involved in designing an experiment to map neural connections using anterograde (red) or retrograde (blue) AAV vectors.

The molecular mechanism of AAV trafficking within the neuron is summarized in the following pathway diagram.

Figure 2: Intracellular Trafficking Pathway of AAV. This diagram visualizes the dual transport mechanisms of AAV within a neuron after endocytosis. The virus in Rab7-positive late endosomes is transported retrogradely by dynein towards the soma or anterogradely by kinesin-2 towards the axon terminal [19] [20].

AAV-based viral vectors provide a powerful and versatile toolkit for dissecting the complex wiring of the brain. Understanding the distinct axonal transport mechanisms—anterograde and retrograde—enables researchers to select the appropriate serotype (e.g., AAV1 or AAV-retro) and design rigorous protocols for mapping neural inputs and outputs. The continued development of engineered capsids with enhanced tropism and the refinement of intersectional genetic strategies promise to further accelerate the precise functional dissection of neural circuits, advancing both fundamental neuroscience and the development of gene therapies for neurological disorders.

The Armamentarium for Precision Brain Cell Access is a transformative project under the NIH BRAIN Initiative, established to develop and disseminate a comprehensive collection of molecular genetic reagents [25]. Its primary goal is to enable neuroscientists to target specific brain cell types with high precision, facilitating the study of neural circuits in both laboratory animals and human tissue specimens [25]. This initiative aims to bring the precision of molecular targeting to specific neural circuits that underlie behavior and network function, potentially revolutionizing our understanding of the brain and informing new approaches for treating neurological disorders [25].

A key driver for the Armamentarium is the need to extend precision targeting to less genetically tractable organisms, such as non-human primates, which are critical for understanding the human brain [25]. While genetically engineered animals like transgenic mice have enabled considerable progress, the Armamentarium focuses on developing non-transgenic tools (e.g., engineered viral vectors) for species where traditional genetic models are not feasible [25]. The project encompasses multiple funded efforts, including the development of molecular genetic access reagents, optimization of functional probes for delivery, widespread dissemination of reagents to the neuroscience community, and building research infrastructure [25].

Viral vectors are the cornerstone of modern neural circuit manipulation, providing the means to deliver genetic instructions for sensors and actuators to specific cell types. The table below summarizes the key viral vectors used in neuroscience research, highlighting their characteristics and primary applications in neural circuit mapping and manipulation [17].

Table 1: Viral Vectors for Neural Circuit Mapping and Manipulation

| Virus Type | Genome Size | Vector Capacity | Cytotoxicity | Transport Characteristics | Primary Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adeno-associated Virus (AAV) | ~4.7 kb | ~4.7 kb | Low | Anterograde, non-transsynaptic; AAV1 at high titer can be anterograde trans-monosynaptic; AAV-retro enables efficient retrograde access [17]. | Gene delivery for optogenetics, chemogenetics, and sensors; circuit mapping [17]. |

| Rabies Virus (RV), glycoprotein G-deleted (RVdG) | ~12 kb | ~3.7 kb | High | Complete retrograde transport; efficient infection of axon terminals; EnvA-pseudotyped RVdG enables retrograde trans-monosynaptic tracing [17]. | Retrograde trans-monosynaptic tracing to map direct inputs to starter cells [17]. |

| Herpes Simplex Virus Type 1 (HSV1) H129 | ~150 kb | ~50 kb | High | Anterograde trans-multisynaptic trafficking [17]. | Anterograde polysynaptic circuit mapping of output networks [17]. |

| Canine Adenovirus (CAV-2) | ~31 kb | ~30 kb | Moderate | Preferentially transduces neuronal axon terminals with efficient retrograde transport [17]. | Retrograde access to neurons projecting to an injection site [17]. |

The selection of an appropriate viral vector depends on the experimental goal, such as the direction of tracing (anterograde vs. retrograde), the desired synaptic specificity (monosynaptic vs. polysynaptic), and the payload size required.

Table 2: Comparison of Viral Strategies for Circuit Mapping

| Strategy | Tracing Direction | Synaptic Specificity | Key Viral Tools | Ideal Use Cases |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anterograde Tracing | Forward (maps outputs) | Non-synaptic, monosynaptic, or polysynaptic | AAV (non-synaptic), AAV1 high-titer (monosynaptic), HSV1-H129 (polysynaptic) [17] | Mapping the projections and synaptic outputs of a specific neuronal population. |

| Retrograde Tracing | Backward (maps inputs) | Non-synaptic, monosynaptic, or polysynaptic | CAV-2, AAV-retro (non-synaptic), EnvA+RVdG (monosynaptic), PRV (polysynaptic) [17] | Identifying the source of inputs to a defined population of "starter" cells. |

| Cell-Type Specific Targeting | N/A | N/A | AAVs with cell-specific promoters or Cre-dependent (DIO) systems [26] [17] | Manipulating or monitoring a genetically defined cell type without regard to its connections. |

| Projection-Specific Targeting | N/A | N/A | AAVs with retrograde functionality (e.g., CAV-Cre) combined with Cre-dependent AAVs [17] | Accessing neurons based on both their cell type and their long-range projection targets. |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Retrograde Monosynaptic Tracing with RVdG

This protocol details the use of glycoprotein-deleted Rabies Virus (RVdG) for mapping the direct, monosynaptic inputs to a genetically defined population of "starter" neurons [17].

1. Principle: The method involves a two-step, helper virus system. First, "starter cells" are genetically defined and made to express the missing rabies glycoprotein (RG) and a fluorescent marker (e.g., TVA receptor for EnvA-pseudotyping). In the second step, the RVdG vector, which lacks the gene for glycoprotein (G), is injected. This virus can only infect the starter cells (via TVA) and can only spread retrogradely to their direct presynaptic partners because those partners lack the glycoprotein required to package new, infectious viral particles [17].

2. Materials:

- Plasmid DNA: Plasmids encoding TVA (receptor for EnvA-pseudotyped virus) and Rabies Glycoprotein (RG).

- Helper Viral Vectors: AAV vectors for delivering TVA and RG genes, or a transgenic mouse line expressing TVA and RG in a Cre-dependent manner.

- Tracing Viral Vector: EnvA-pseudotyped, G-deleted Rabies Virus (RVdG) encoding a fluorescent reporter (e.g., mCherry).

- Stereotaxic surgery equipment, including microsyringe pump and fine-glass micropipettes.

3. Step-by-Step Procedure: 1. Stereotaxic Injection of Helper Components: Inject the AAV helper viruses (e.g., AAV-FLEX-TVA and AAV-FLEX-RG) into the target brain region of a Cre-driver mouse. Alternatively, use a transgenic mouse line that already expresses TVA and RG in a Cre-dependent manner. - Parameters: Use a microsyringe pump for controlled injection (e.g., 50-100 nL/min). Allow 2-4 weeks for adequate expression of the helper proteins. 2. Stereotaxic Injection of RVdG: Inject the EnvA-pseudotyped RVdG-mCherry into the same coordinates. - Parameters: The virus titer should be > 1x10^8 infectious units/mL. Allow 5-7 days for retrograde trans-monosynaptic spread. 3. Perfusion and Tissue Processing: Transcardially perfuse the animal with 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA). Extract the brain and post-fix in 4% PFA for 24 hours, then section into 50-100 µm thick slices using a vibratome. 4. Imaging and Analysis: Image the brain sections using a slide scanner or confocal microscope. The starter cells (co-expressing the helper virus fluorophore and mCherry) and the direct presynaptic input neurons (expressing only mCherry) can be identified and quantified.

4. Critical Considerations:

- Specificity: The starter cell population must be precisely defined, as only these cells will initiate the trans-synaptic spread.

- Cytotoxicity: RVdG is cytotoxic; the analysis must be completed within 1-2 weeks post-injection to avoid degradation of the signal and loss of infected neurons [17].

- Controls: Always include controls without the helper viruses to confirm the absence of non-specific RVdG infection.

Protocol 2: Cell-Type Specific Neural Circuit Manipulation

This protocol combines Cre-recombinase driver lines with Cre-dependent AAVs to achieve cell-type specific expression of optogenetic actuators for functional circuit manipulation [26] [17].

1. Principle: A Cre-dependent (DIO or FLEX) AAV vector, which contains an inverted coding sequence for an opsin (e.g., Channelrhodopsin-2), is injected into a specific brain region of a transgenic mouse expressing Cre-recombinase under a cell-type specific promoter. Cre-mediated recombination flips the inverted sequence into the correct orientation, allowing opsin expression exclusively in the targeted cell population. An implanted optical fiber then allows light delivery to manipulate the activity of these neurons [26].

2. Materials:

- Animal Model: Transgenic Cre-driver mouse line.

- Viral Vector: Cre-dependent AAV (e.g., AAV5-EF1α-DIO-ChR2-eYFP).

- Optogenetics System: Laser or LED light source, optical fibers, ferrule, fiber-optic patch cord.

- Stereotaxic surgery equipment, including drill and microsyringe pump.

- Behavioral apparatus and electrophysiology setup for functional validation.

3. Step-by-Step Procedure: 1. Stereotaxic Viral Injection: Inject the Cre-dependent AAV into the target brain region of the anesthetized Cre-driver mouse. - Parameters: Use a titer of > 1x10^12 vg/mL. Inject 200-500 nL at a slow flow rate (50-100 nL/min). Leave the pipette in place for 5-10 minutes post-injection to prevent backflow. 2. Optical Cannula Implantation: Immediately following the viral injection, implant a chronic optical cannula above the injection site and secure it to the skull with dental cement. 3. Recovery and Expression: Allow the animal to recover for at least 3-4 weeks to ensure robust opsin expression. 4. Functional Validation: - Ex vivo: Conduct patch-clamp recordings in brain slices to confirm light-evoked spiking in ChR2-expressing neurons. - In vivo: Connect the implanted cannula to a patch cord and deliver light pulses (e.g., 5-20 ms pulses of 473 nm blue light) during behavioral tasks to assess the causal role of the manipulated circuit.

4. Critical Considerations:

- Opsin Selection: Choose an opsin with kinetics and light sensitivity appropriate for the experiment (e.g., ChR2 for millisecond-scale activation, stabilized step-function opsins for sustained activation) [26].

- Light Power: Titrate light power to achieve effective neural modulation without causing thermal damage.

- Off-Target Effects: Verify opsin expression and function histologically and physiologically post-experiment.

Visualization of Core Workflows and Signaling Pathways

Workflow for Monosynaptic Circuit Tracing

This diagram illustrates the core principle and workflow for retrograde monosynaptic tracing using the helper virus and RVdG system.

Logic of Cell-Type Specific Targeting

This diagram outlines the genetic strategy for achieving cell-type specific transgene expression using the Cre-loxP system and engineered AAVs.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

The following table catalogs essential reagents and tools provided by the Armamentarium and associated BRAIN Initiative efforts for precision neuroscience.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Precision Neural Circuit Analysis

| Reagent/Tool Category | Specific Examples | Function and Application |

|---|---|---|

| Viral Vector Systems | AAV serotypes (e.g., AAV1, AAV5, AAV9), AAV-retro, DIO/FLEX AAVs, RVdG, CAV-2, HSV1-H129 [25] [17]. | Deliver genetic payloads (sensors, actuators, Cre recombinase) to specific cell types or circuits based on tropism and route of administration. |

| Cell Type Access Reagents | Cre-driver transgenic lines; AAVs with cell-specific promoters; transgenic mice expressing TVA and RG for rabies tracing [25] [17]. | Genetically define and gain experimental access to specific neuronal or glial cell populations for manipulation or monitoring. |

| Genetically Encoded Actuators | Channelrhodopsins (ChR2), Halorhodopsins (NpHR), Chemogenetic Receptors (DREADDs) [26] [17]. | Precisely activate or inhibit targeted neuronal populations with light (optogenetics) or inert ligands (chemogenetics) to test causal roles in circuits and behavior. |

| Genetically Encoded Sensors | Calcium indicators (GCaMP), voltage-sensitive fluorescent proteins (VSFP), iGluSnFR [27]. | Monitor neural activity (calcium influx, membrane potential, neurotransmitter release) in specific cell types during behavior or processing. |

| Molecular Profiling Tools | Single-cell RNA sequencing, spatial transcriptomics, ATAC-seq, antibody panels from BICCN [28]. | Characterize and classify the molecular identity of brain cell types, enabling the definition of target populations for the Armamentarium. |

The BRAIN Initiative Armamentarium represents a paradigm shift in neuroscience methodology, moving the field from observation to causal dissection of neural circuits with cellular and synaptic precision. By providing a centralized, validated, and expanding toolkit of molecular reagents for cell-type-specific access, the Armamentarium empowers researchers to deconstruct the functional architecture of the brain systematically [25]. The integration of these tools with other BRAIN Initiative projects, such as the Brain Initiative Cell Census Network (BICAN) and the BRAIN CONNECTS program, creates a powerful synergistic framework for understanding the brain from molecules to circuits to behavior [25] [28].

Looking forward, the focus will be on refining these tools for enhanced specificity, lower immunogenicity, and greater utility in non-human primates and human-derived tissue models, thereby accelerating the translational path for treating brain disorders [25]. The continued development and dissemination of these precision delivery tools are fundamental to achieving the BRAIN Initiative's ultimate vision: a comprehensive, mechanistic understanding of mental function that paves the way for novel therapeutic interventions [29].

Precisely defining neural cell types is a fundamental prerequisite for modern neuroscience research aimed at understanding brain function and dysfunction. The incredible cellular heterogeneity of the brain means that even microscopically discrete regions contain multiple cell types with distinct functions, connectivity, and molecular signatures. Early lesion and electrical stimulation techniques, while groundbreaking, lacked the specificity to target these distinct cellular populations, often leading to confounding results from affecting multiple circuit elements simultaneously [30] [31]. The advent of genetic tools has revolutionized this landscape, enabling researchers to move beyond crude anatomical targeting to precise manipulation based on a neuron's genetic identity or its connectivity within a circuit [31].

This shift in methodology is particularly critical for gene delivery strategies in neural circuit research. The ability to deliver genes encoding functional actuators (e.g., for optogenetics or chemogenetics) or reporters (e.g., for activity monitoring or tracing) to specific cell types relies entirely on our capacity to define and target those populations using unique molecular markers [30] [17]. This protocol outlines the conceptual frameworks and practical methodologies for defining neural cell types and leveraging these definitions for targeted manipulation, providing a foundation for probing circuit function in health and disease.

Core Principles: Genetic and Connectivity-Based Targeting Strategies

Two complementary paradigms form the cornerstone of contemporary neural circuit dissection: targeting by genetic identity and targeting by spatial connectivity. Each approach offers distinct advantages and is suited to different experimental questions.

Genetic Identity

This approach exploits the unique gene expression profiles of neuronal subtypes to achieve specificity. Defined by transcription factors, neurotransmitter systems, calcium-binding proteins, or other molecular markers, this genetic identity often reflects a neuron's developmental history and functional role [31]. In practice, this is achieved by placing transgenes under the control of cell-type-specific promoter regions. For example, promoters for vesicular glutamate transporter 2 (Vglut2) target glutamatergic neurons, while promoters for calcium/calmodulin kinase II alpha (CaMKIIα) target forebrain neurons [31]. Transgenic mouse lines expressing Cre recombinase under the control of such promoters (e.g., the Crym promoter for corticospinal neurons) allow for flexible genetic access to these defined populations [31]. The primary advantages of this method are its non-invasiveness when using germline transgenics and its comprehensive coverage of the targeted cell type throughout the brain [31].

Spatial Control (Connectivity-Based Targeting)

This strategy uses the physical connectivity of a circuit—its origin and termination points—to achieve specificity. It involves introducing one genetic element at the cell bodies of origin (e.g., via an anterograde virus) and another at the axonal terminals (e.g., via a retrograde virus) [31]. Only neurons that are co-infected with both viruses—and thus form that specific connection—will express the transgene required for manipulation. This approach is powerful for dissecting circuits defined by their wiring rather than their molecular signature and allows for targeting specific projections from a heterogeneous region [31]. These two general approaches can be combined for even greater precision, such as by introducing a regulatory gene into the origin or termination of a circuit to manipulate neurons with a specific genetic identity within that pathway [31].

Table 1: Core Strategies for Defining and Targeting Neural Cell Types

| Strategy | Basis for Specificity | Key Tools | Primary Advantage | Common Application |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Genetic Identity | Unique gene expression profile (e.g., transcription factors, neurotransmitters) | Cell-type-specific promoters (e.g., Vglut2, CaMKIIα); Cre/Lox and Flp/FRT recombinase systems [31] | Non-invasive; comprehensive coverage of a defined cell type across the brain [31] | Manipulating all neurons of a specific molecular class (e.g., all GABAergic neurons) |

| Spatial Control (Connectivity) | Physical wiring from point A to point B | Combinatorial viral delivery (anterograde + retrograde) [31]; Retrogradely transported viruses (e.g., CAV-2, AAV-retro) [17] | Targets circuits based on function rather than molecular identity; projects specificity from heterogeneous regions [31] | Isolating a specific pathway (e.g., prefrontal-to-amygdala projection) |

Essential Genetic Tools for Cell-Type Specificity

The implementation of the above strategies relies on a sophisticated genetic toolbox, with site-specific recombination systems serving as the core engine for precise targeting.

Site-Specific Recombination and Intersectional Genetics

Site-specific recombination (SSR) systems, most commonly Cre/loxP and Flp/FRT, allow for conditional expression of transgenes in genetically defined cells [30]. In these systems, a recombinase (Cre or Flp) is expressed under the control of a cell-type-specific promoter. This recombinase then acts on its target sites (loxP or FRT) that have been engineered to flank a "stop" cassette in a separate reporter or effector construct. The removal of the stop cassette activates expression of the downstream gene, ensuring it is only turned on in the desired cell type [30]. This is often achieved using the "Lox-Stop-Lox" (LSL) or "double-inverted orientation" (DIO, also known as FLEX) methods, the latter being particularly useful in viral vectors [30].

Intersectional genetics takes this specificity a step further by requiring the coincidence of two genetic features. For example, a neuron might only express a transgene if it expresses both Cre and Flp recombinases [30]. This allows for targeting of highly specific neuronal subpopulations that are defined by the overlap of two genetic markers, dramatically increasing precision beyond what is possible with a single promoter.

Activity-Dependent Targeting

Beyond static genetic identity, neurons can also be defined by their activity patterns during specific behaviors or states. Technologies such as TRAP (Targeted Recombination in Active Populations) and FLiCRE (Fast Light and Calcium-Regulated Expression) allow for permanent genetic labeling of neurons that are active during a defined time window [30]. In TRAP, administration of tamoxifen triggers Cre recombinase activity only in neurons that are simultaneously expressing the activity-dependent immediate early gene cfos [30]. FLiCRE uses a light- and calcium-dependent enzyme to label active neurons with high temporal precision [30]. These approaches enable researchers to tag and later manipulate functional ensembles, rather than just molecularly defined populations.

Diagram Title: Logic Flow for Targeted Neural Circuit Manipulation

Viral Vectors for Delivery of Genetic Tools

Viral vectors are the workhorses for delivering genetic tools to specific neural populations, with adeno-associated viruses (AAVs) being the most widely used due to their safety, low immunogenicity, and ability to achieve stable long-term expression [17].

Key Viral Vector Characteristics

- Adeno-Associated Virus (AAV): A replication-defective virus with a ~4.7 kb single-stranded DNA genome. Different serotypes exhibit tropism for different cell types. It is primarily anterograde and non-transsynaptic, ideal for labeling axonal projections, though AAV1 at high titers can show anterograde trans-monosynaptic transmission [17].

- Rabies Virus (RV): A retrograde, transsynaptic virus. The glycoprotein-deleted variant (RVdG) is used for retrograde tracing from a defined starter population in a monosynaptic manner, allowing for mapping of direct inputs [17].

- Herpes Simplex Virus (HSV1-H129): An anterograde, transsynaptic tracer with a large DNA genome, allowing for a big insert capacity. Used for mapping output circuits [17].

- Canine Adenovirus (CAV-2): A retrograde vector that preferentially transduces neuronal axon terminals, useful for retrograde access to projection neurons [17].

Table 2: Viral Vectors for Neural Circuit Mapping and Manipulation

| Virus | Genome Size / Capacity | Transport Direction | Transsynaptic Capability | Primary Use Case |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| AAV | ~4.7 kb / ~4.7 kb [17] | Predominantly anterograde [17] | Low (AAV1 can be anterograde monosynaptic at high titer) [17] | General gene delivery; anterograde tracing; expression of actuators/sensors |

| AAV-retro | ~4.7 kb / ~4.7 kb [17] | Efficient retrograde [17] | No | Retrograde access to projection neurons from a terminal field |

| RVdG | ~12 kb / ~3.7 kb [17] | Complete retrograde [17] | Monosynaptic (when complemented) | Monosynaptic input mapping to a defined starter cell population |

| HSV1-H129 | ~150 kb / ~50 kb [17] | Anterograde [17] | Polysynaptic (monosynaptic variants exist) | Anterograde output mapping across multiple synapses |

| CAV-2 | ~31 kb / ~30 kb [17] | Retrograde [17] | No | Efficient retrograde labeling from axon terminals |

Detailed Protocols for Targeted Manipulation

The following protocols integrate the principles and tools described above to outline specific methodologies for defining and manipulating neural circuits.

Protocol 1: Intersectional Targeting of a Specific Projection Pathway

Aim: To selectively express an optogenetic actuator in a genetically defined population that projects from Brain Region A to Brain Region B.

Workflow:

- Starter Cell Definition: Inject an AAV expressing Cre recombinase in a retrograde manner (e.g., AAV-retro or CAV-2-Cre) into the terminal field (Region B). This will deliver Cre retrogradely to neurons in Region A that project to Region B.

- Effector Delivery: In the same animal, inject a Cre-dependent AAV (e.g., DIO-ChR2) into the region of the cell bodies (Region A).

- Intersectional Expression: Only neurons in Region A that project to Region B (and thus received the retrograde Cre) will express the Cre-dependent ChR2. Neighboring neurons in Region A that project elsewhere will not be transfected.

Diagram Title: Intersectional Targeting of a Specific Projection

Protocol 2: Monosynaptic Input Mapping with Rabies Virus

Aim: To identify all direct presynaptic partners (inputs) of a genetically defined population of "starter" neurons.

Workflow:

- Label Starter Cells: Inject a Cre-dependent AAV expressing (a) a fluorescent protein (e.g., EGFP) and (b) the essential rabies glycoprotein (oG) into the target brain region of a Cre-driver mouse.

- Complement RVdG: After 3-4 weeks, inject the modified rabies virus (RVdG) that is EnvA-pseudotyped (to limit infection to cells expressing the TVA receptor) and encodes a different fluorescent protein (e.g., mCherry). The starter cells, which express oG, will package and release infectious RVdG particles.

- Transsynaptic Spread: The newly packaged RVdG spreads retrogradely, across one synapse, to infect the direct presynaptic neurons. These input neurons will express mCherry but cannot produce infectious particles because they lack oG, limiting the spread to one step.

Protocol 3: Functional Manipulation Using DREADDs

Aim: To chronically inhibit or excite a defined neural population during a behavioral task.

Workflow:

- Target and Deliver: Inject a Cre-dependent AAV encoding either the inhibitory (hM4Di) or excitatory (hM3Dq) DREADD into the target brain region of a Cre-driver mouse.

- Express and Recover: Allow 3-4 weeks for adequate expression of the DREADD receptor in the target cells.

- Administer Ligand: Systemically administer the inert designer drug Clozapine-N-Oxide (CNO) (typically 1-5 mg/kg, i.p.) 30-60 minutes before behavioral testing. CNO binding to hM4Di silences neuronal activity, while binding to hM3Dq increases it.

- Assess Behavior: Compare task performance (e.g., memory retrieval, fear expression, feeding) between CNO and vehicle sessions to infer the circuit's function.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Reagent Solutions for Targeted Neural Circuit Research

| Reagent / Tool | Category | Function in Experiment |

|---|---|---|

| Cre/loxP & Flp/FRT Systems | Genetic Engine | Enables conditional, cell-type-specific expression of transgenes via site-specific recombination [30]. |

| AAV (Various Serotypes) | Viral Delivery Vehicle | Safely and efficiently delivers genetic cargo (opsins, DREADDs, sensors) to specific brain regions with cell-type specificity using Cre-dependent constructs [17]. |

| Rabies Virus (RVdG) | Viral Tracer | Maps monosynaptic inputs to a defined "starter" cell population when complemented with helper proteins (TVA and oG) [17]. |

| Channelrhodopsin-2 (ChR2) | Optogenetic Actuator | A light-sensitive cation channel that depolarizes and excites neurons upon blue light exposure, allowing for millisecond-timescale control [32]. |

| Halorhodopsin (NpHR)/Archaerhodopsin (Arch) | Optogenetic Actuator | Light-sensitive chloride or proton pumps that hyperpolarize and silence neurons upon yellow/green light exposure [32]. |

| DREADDs (hM3Dq, hM4Di) | Chemogenetic Actuator | Engineered GPCRs that modulate neuronal activity (excite or inhibit, respectively) for tens of minutes to hours upon administration of the inert ligand CNO [32]. |

| GCaMP | Neural Activity Sensor | A genetically encoded calcium indicator whose fluorescence increases with neuronal spiking, allowing for optical monitoring of population activity [32]. |

Engineering Precision: AAV Serotypes, Promoters, and CRISPR Integration

The precise manipulation of neural circuits for research and therapeutic purposes is critically dependent on the selective targeting afforded by specific adeno-associated virus (AAV) serotypes. This application note details the specialized use of three powerful capsids: PHP.eB for widespread central nervous system (CNS) transduction following intravenous administration, PHP.S for peripheral nervous system (PNS) targeting, and AAV2-retro for efficient high-resolution retrograde tracing of neural projections. We provide a structured comparison of their properties, summarized in the table below, alongside detailed protocols and essential reagent solutions to facilitate their effective implementation in gene delivery strategies for neural circuit dissection.

Table 1: Key Characteristics of Specialized AAV Serotypes

| Feature | PHP.eB | PHP.S | AAV2-Retro |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary Application | Widespread CNS transduction from bloodstream [33] | Peripheral Nervous System (PNS) targeting [33] | Efficient retrograde access to projection neurons [34] [35] |

| Key Advantage | Efficiently crosses the blood-brain barrier (BBB) [33] | Enhanced tropism for peripheral tissues [33] | Retrograde transport efficiency comparable to classical tracers [35] |

| Injection Route | Intravenous (IV) [36] | Intravenous (IV) / Intraperitoneal (IP) | Focal injection into axon terminal fields [34] [18] |

| Tropism | Broad CNS cell types (neurons, astrocytes, oligodendrocytes) | DRG neurons, motor neurons, other PNS tissues | Projection neurons defined by injection site [34] [35] |

| Reported Transduction Efficiency | High throughout CNS after IV delivery [34] [33] | High in PNS tissues (e.g., dorsal root ganglia) [33] | Robust labeling in afferent brain regions (e.g., cortex, striatum) [34] [35] |

Serotype Profiles and Experimental Applications

PHP.eB for Central Nervous System (CNS) Transduction

PHP.eB is an engineered capsid derived from AAV9, selected for its superior ability to cross the blood-brain barrier (BBB) after systemic administration [33]. This property enables robust, non-invasive gene delivery to the brain and spinal cord without the need for direct intracranial injection, making it a transformative tool for modeling and treating global CNS diseases [34] [33].

Key Workflow: The standard protocol involves intravenous injection (e.g., via jugular or tail vein) of high-titer PHP.eB vectors ( [36], see Section 3.1 for detailed protocol). The virus circulates, binds to receptors on CNS vasculature, and is transcytosed into the brain parenchyma. For example, injection into deep cerebellar nuclei results in transduction of Purkinje cells, demonstrating its widespread reach [34].

AAV2-Retro for Efficient Retrograde Tracing

AAV2-retro is a specially engineered variant designed for highly efficient retrograde transport [35]. When injected into a brain region containing axonal terminals, the virus is internalized and transported backward along the axon to the connected neuronal cell bodies, enabling researchers to map and manipulate the inputs to a specific site [18] [35].

Key Workflow: AAV2-retro is delivered via precise, low-volume focal injection into the brain region of interest (e.g., basal pontine nuclei or striatum) [34] [35]. The virus is then taken up by axon terminals present in that region and retrogradely transported. This leads to transgene expression in the somata of projecting neurons, which can be located in remote regions such as the cortex or substantia nigra [34]. This process is summarized in the diagram below.

PHP.S for Peripheral Nervous System (PNS) Targeting

PHP.S is part of the same engineered family as PHP.eB but has been optimized for enhanced transduction of the PNS, including dorsal root ganglia (DRG) and motor neurons, after systemic delivery [33]. This serotype is invaluable for studying sensory perception, pain, and peripheral neuropathies. A related capsid, AAV-ROOT, was specifically developed for retrograde tracing from peripheral organs like adipose tissue to DRG neurons, demonstrating the power of specialized serotypes for PNS circuit mapping [37].

Quantitative Serotype Comparison

Selecting the optimal AAV serotype requires a comparative understanding of their performance across multiple metrics. The table below synthesizes data from key studies to guide this decision.

Table 2: Comparative Performance of AAV Serotypes in Neural Targeting

| Serotype | Injection Site | Target Region/Cell Type | Key Quantitative Finding/Note | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PHP.eB | Deep Cerebellar Nuclei | Purkinje Cells | Efficient transduction from a distal injection site. | [34] |

| AAV2-retro | Basal Pontine Nuclei (BPN) | Layer V Cortical Neurons | Dense labeling of afferent neurons in a highly convergent pathway. | [35] |

| AAV2-retro | Striatum | Substantia Nigra Neurons | Labels neurons projecting to the injection site. | [34] |

| AAV9 | Striatum | Substantia Nigra | Demonstrates natural, though less efficient, retrograde transport. | [34] |

| AAV5 | Hippocampus (Dentate Gyrus) | Entorhinal Cortex | Labeled cells co-localized with the retrograde tracer CTB. | [34] [38] |

| AAV-DJ | CNS (ICV/IT administration) | Widespread Brain & Spinal Cord | Significantly increased vector genome uptake in CNS vs. AAV9. | [36] |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Intravenous (IV) Delivery of PHP.eB for CNS Transduction

This protocol is adapted from methods used to compare AAV9 and AAV-DJ, applicable for PHP.eB [36].

Materials:

- Purified PHP.eB vector (e.g., ~1x10^13 vg/kg in 150 µL for mice [36])

- Anesthetic (e.g., 1-3% isoflurane)

- Sterile surgical tools (scissors, forceps)

- 28-30 gauge insulin syringe or catheter

- Analgesic (e.g., Meloxicam, 0.5 mg/kg)

Procedure:

- Anesthetize the mouse and secure it in a supine position.

- Perform a small incision (~0.5 cm) in the neck parallel to the midline to expose the external jugular vein.

- Slowly inject the viral preparation (e.g., 150 µL) into the vein using a bent 28-gauge needle.

- Apply gentle pressure for hemostasis upon needle withdrawal and close the incision with tissue adhesive.

- Administer analgesic subcutaneously and monitor the animal post-operatively according to IACUC guidelines.

- Allow 2-4 weeks for robust transgene expression before analysis.

Protocol: Focal Stereotaxic Injection of AAV2-retro for Circuit Mapping

This standard protocol for intracranial injection is used for AAV2-retro [34] [35].

Materials:

- AAV2-retro vector (high titer, ≥10^12 vg/mL)

- Stereotaxic apparatus

- Microsyringe (e.g., Hamilton, 26-gauge) or glass micropipette

- Anesthetic (e.g., ketamine/xylazine or isoflurane)

Procedure:

- Anesthetize the mouse and fix its head securely in the stereotaxic frame.

- Expose the skull through a midline scalp incision and identify Bregma and Lambda.

- Calculate target coordinates for the brain region of interest (e.g., striatum, basal pontine nuclei).

- Drill a small craniotomy at the calculated coordinates.

- Lower the needle slowly to the target depth.

- Infuse the virus (e.g., 50-500 nL at a rate of 50-100 nL/min) to minimize tissue damage and backflow.

- Leave the needle in place for 5-10 minutes post-injection before slow withdrawal.

- Suture the wound and provide post-operative care.

- Allow 2-4 weeks for retrograde transport and transgene expression.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for AAV-Based Neural Circuit Research

| Reagent / Tool | Function | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| AAV2-retro Capsid Plasmid | Packaging plasmid for producing AAV2-retro viral particles. | Enables high-titer production of AAV2-retro for retrograde tracing experiments [39]. |

| AAV Helper Plasmid | Provides adenoviral helper functions (e.g., E4, VA, E2A) essential for AAV production. | Co-transfected with Rep/Cap and ITR-containing vector during AAV packaging [39]. |

| Cre-Dependent AAV Vectors | AAVs with a flipped transgene that is only expressed in the presence of Cre recombinase. | Restricts transgene expression to Cre-positive, retrogradely labeled cells for cell-type-specific manipulation [18]. |

| Cholera Toxin Subunit B (CTB) | A classical, non-viral retrograde tracer. | Used to validate the retrograde transport efficiency of AAV vectors via co-injection and co-localization [34] [38]. |

| Transgenic Cre Mouse Lines | Mice expressing Cre recombinase under a cell-type-specific promoter. | Provides genetic access to specific neuronal populations for intersectional targeting with retrograde AAVs [18]. |

Integrated Workflow for Intersectional Neural Circuit Manipulation

Combining AAV2-retro with Cre-lox technology represents a powerful strategy for achieving input-specific manipulation of defined neuronal populations. The following diagram and protocol outline this advanced workflow.

Procedure:

- Select an appropriate transgenic mouse expressing Cre recombinase in a neuronal population of interest (e.g., hippocampal neurons).

- Inject an AAV2-retro vector expressing Cre (not a Cre-dependent vector) into a target region receiving projections from these neurons (e.g., Broca's area analog). The virus will be retrogradely transported to the cell bodies in the Cre-positive population [18].

- In a second surgery, inject a Cre-dependent AAV (e.g., expressing a DREADD or channelrhodopsin) directly into the brain region containing the Cre-positive cell bodies (e.g., the hippocampus). This ensures the effector is only present where Cre is expressed.

- The effector transgene is activated only in the specific projection neurons (e.g., hippocampus → Broca's area) that were retrogradely accessed, allowing for precise functional manipulation [18]. This two-step method avoids spurious expression at the injection site of the retrograde vector.

Precise genetic manipulation of specific neural cell types is fundamental to advancing our understanding of brain function and developing targeted therapies for neurological disorders. The choice of promoter represents a critical determinant of specificity in gene delivery systems, controlling both the level and cellular localization of transgene expression. Within the context of neural circuit manipulation, three promoters have emerged as essential tools for targeting major neural cell populations: the human synapsin 1 (hSyn) promoter for neurons, the glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP) promoter for astrocytes, and the CD68 promoter for microglia.