Neuroplasticity in Addiction: From Maladaptive Rewiring to Therapeutic Recovery

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of the dual role of neuroplasticity in substance use disorders, exploring both its contribution to addiction development and its potential as a mechanism for...

Neuroplasticity in Addiction: From Maladaptive Rewiring to Therapeutic Recovery

Abstract

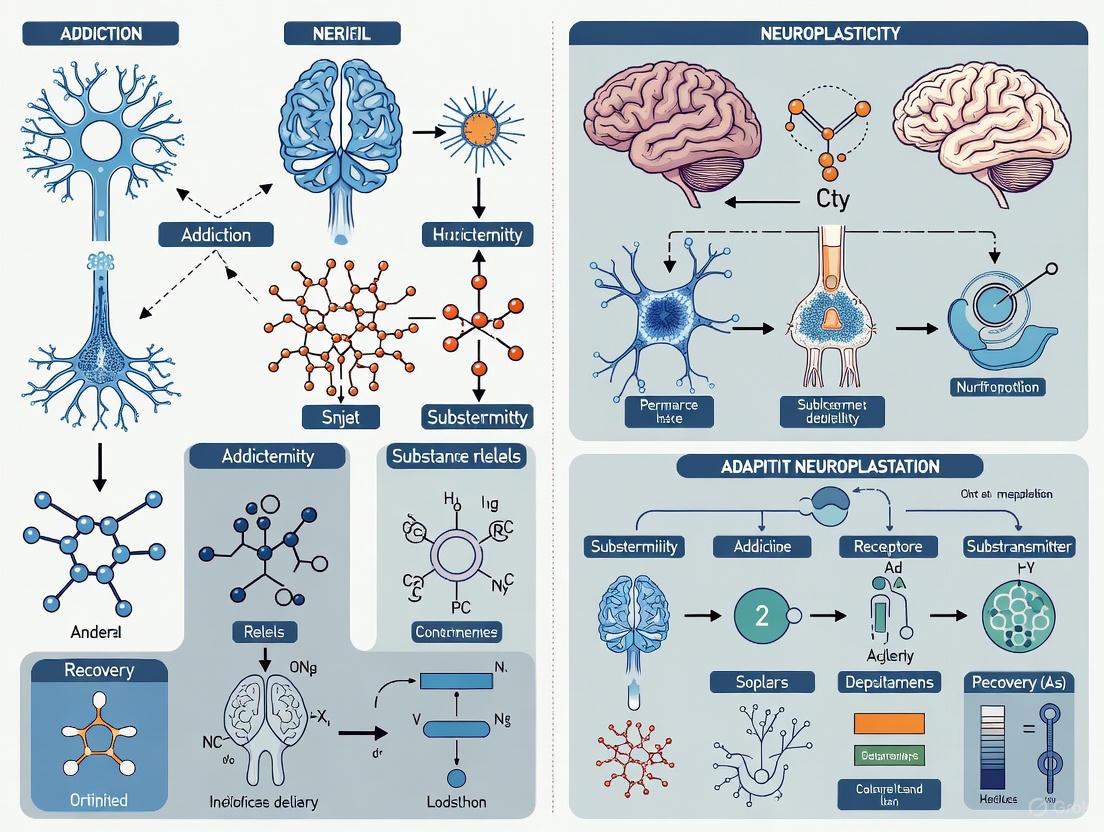

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of the dual role of neuroplasticity in substance use disorders, exploring both its contribution to addiction development and its potential as a mechanism for recovery. Aimed at researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it synthesizes foundational neuroscience with emerging methodological approaches. The content covers the brain's reward system hijacking, the addiction cycle, novel therapeutic targets like neuroinflammation and gasotransmitters, and advanced assessment tools such as high-content imaging and VEP-based biomarkers. It further evaluates comparative intervention strategies, discusses troubleshooting for translational challenges, and outlines future directions for biomarker development and non-canonical organ system research to guide next-generation therapeutics.

The Hijacked Brain: Foundational Mechanisms of Neuroplasticity in Addiction Pathology

Substance use disorders (SUDs) represent a critical challenge to global health, affecting millions of individuals worldwide and exerting a tremendous economic and social cost [1]. Traditional approaches to understanding addiction have often focused on its characterization as a personality disorder or moral failing. However, a more profound explanatory framework emerges when examining addiction through the lens of human evolution. This whitepaper posits that addiction arises from a fundamental mismatch between our ancient neurobiological wiring and our modern environment of abundant, potent rewards [2]. The very neural pathways and reward systems that evolved to ensure survival in environments of scarcity have been hijacked by contemporary substances and behaviors, creating a pervasive biological vulnerability.

This document will explore the evolutionary origins of this vulnerability, detailing the conserved brain systems involved. It will then delineate how modern research methodologies are uncovering the precise molecular and circuit-level mechanisms of addiction. Finally, within the context of a broader thesis on neuroplasticity, this review will chart a course for therapeutic development, arguing that the brain's inherent plasticity—the very substrate upon which addiction writes its damaging script—also provides the most promising avenue for recovery and lasting change.

Evolutionary Origins of a Vulnerable Brain

The Ancient Reward System

The human brain's reward circuitry is not a recent evolutionary development but a deeply conserved system shared across mammalian species and beyond. This system is primed to reinforce behaviors essential for survival and procreation, such as eating, drinking, and social bonding [2]. The mesolimbic dopamine pathway serves as the cornerstone of this system. Dopamine, originating in the ventral tegmental area (VTA) and projecting to the nucleus accumbens (NAc), mediates excitatory processes that promote focus, motivation, and the reinforcement of adaptive behaviors [3]. From an evolutionary standpoint, pursuing activities that release dopamine was, until recently, synonymous with pursuing behaviors critical for fitness.

The Co-Evolutionary Hypothesis: Archaeological evidence suggests a long and intertwined history between mammals and psychotropic plants. Receptor systems in the mammalian brain, such as the opioid receptor system, exist for plant substances not endogenously produced by the body [1]. This suggests a history of ecological interaction and co-evolution, where plants evolved psychoactive allelochemicals to deter herbivores, and mammalian brains, in turn, evolved receptor systems and metabolic pathways to interact with these compounds. In ancient environments, these substances were often mild and their availability limited, posing little risk of widespread addiction. They were sometimes viewed as food sources, providing nutritional value and conferring perceived advantages like increased energy and thermal tolerance [1].

The Modern World: An Environment of Abundance

The advent of global commerce and industrial chemistry has created an environment radically different from that in which our brains evolved. We are now inundated with highly refined substances and behaviors engineered to deliver a faster, more intense dopamine surge than anything encountered in nature [2]. This novel environment transforms a once-minor vulnerability into a significant liability.

As Dr. Keith Humphreys of Stanford Medicine notes, "We’ve got an old brain in a new environment... That vulnerability didn’t matter much for 99.9% of human evolution, until global commerce and industrial chemistry made highly addictive substances easy to access" [2]. The brain's ancient wiring, lacking a built-in regulatory system for such potent and readily available stimuli, is easily overwhelmed. The result is a cascade of maladaptive learning, where the brain begins to treat the substance as more important than basic needs like food, safety, or social connection [2].

Modern Experimental Approaches to an Ancient Problem

Contemporary research is dissecting the neurobiological consequences of this evolutionary mismatch using sophisticated tools. The following section details key experimental paradigms and findings.

Key Experimental Models and Findings

Recent studies have employed a multi-level approach to unravel the epigenetic and circuit-level mechanisms that underpin addiction vulnerability and relapse.

Table 1: Key Quantitative Findings from Recent Addiction Studies

| Study Focus | Experimental Model | Key Metric | Result | Implication |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Epigenetic Regulation of Relapse [4] | Rat cocaine self-administration | Relapse-like cocaine seeking | HDAC5 limits Scn4b expression, reducing relapse. | Identified HDAC5/SCN4B as a selective target for cocaine relapse. |

| Structural Brain Recovery [5] | Human PET neuroimaging (Methamphetamine) | Dopamine transporter (DAT) density in striatum | Protracted abstinence recovered lost DATs. | Demonstrated the brain's capacity for neurochemical healing. |

| Lifestyle Intervention Efficacy [3] | Meta-analysis (22 studies, 1,487 participants) | Abstinence Rate (Odds Ratio) | OR = 1.69 (95% CI: 1.44, 1.99), p < .001. | Physical exercise significantly increases abstinence rates. |

Detailed Experimental Protocol: Epigenetic Mechanisms in Relapse

A seminal 2025 study by Wood et al. provides a robust model for investigating relapse mechanisms [4]. The methodology below outlines their comprehensive approach.

Objective: To determine the role of the epigenetic enzyme HDAC5 and the sodium channel auxiliary subunit gene Scn4b in regulating relapse-like drug seeking.

Materials and Methods:

- Animal Model: Adult rats are trained to self-administer intravenous cocaine or a natural reward (sucrose) by pressing a lever, modeling substance use and natural reward-seeking behaviors.

- Extinction Training: The lever press no longer delivers the reward, leading to a gradual reduction in the behavior.

- Relapse Test (Reinstatement): Following extinction, animals are exposed to drug-associated cues or contexts, and lever pressing is measured as a proxy for relapse.

- Multilevel Analysis:

- Molecular: Tandem mass spectrometry and enzymatic activity assays to measure HDAC5 function. Quantitative mRNA analysis to measure gene expression changes in the nucleus accumbens.

- Electrophysiological: Patch-clamp electrophysiology on neurons from the nucleus accumbens to measure changes in neuronal excitability following manipulation of HDAC5 or SCN4B.

- Computational: Modeling of sodium channel properties with and without the SCN4B subunit.

- Behavioral: Comparison of cocaine-seeking vs. sucrose-seeking behaviors following genetic or pharmacological manipulation of the HDAC5-SCN4B pathway.

Key Finding: The study revealed that HDAC5 exerts a protective effect by limiting the expression of Scn4b. The SCN4B protein, in turn, functions to limit the excitability of key neurons in the nucleus accumbens. This pathway selectively limits the formation of powerful, long-lasting drug-cue associations that trigger relapse, without affecting natural reward seeking [4]. This specificity makes the HDAC5-SCN4B axis a novel and promising therapeutic target.

The following diagram illustrates the experimental workflow and the core signaling pathway discovered in this study.

Neuroplasticity: The Double-Edged Sword

The brain's remarkable ability to change its structure and function in response to experience—neuroplasticity—is the central mechanism in both the development of and recovery from addiction [6].

Maladaptive Plasticity in Addiction Development

Repeated dopamine surges from drug use strengthen the connections between the drug-taking behavior, associated environmental cues, and the powerful dopamine response [3]. This process, known as synaptic plasticity, underlies the formation of strong, habit-like drug memories. Concurrently, the brain attempts to maintain homeostasis by downregulating dopamine receptors and their sensitivity, leading to a blunted response to natural rewards and a need for more of the drug to achieve the same effect (tolerance) [2]. This represents a maladaptive form of learning, where "someone might begin using a substance or behavior to have fun or solve a problem, but our brains adapt and we stop getting the same effect" [2]. These changes are further reinforced by neuroinflammation and alterations in other neurotransmitter systems, such as serotonin [3].

Harnessing Adaptive Plasticity for Recovery

The same neuroplasticity that enables addiction also facilitates recovery. The brain retains a lifelong capacity to rewire itself. The core of recovery involves fostering adaptive neuroplasticity to outcompete drug-related patterns [5].

Key Mechanisms of Recovery-Focused Plasticity:

- Structural and Functional Recovery: Longitudinal neuroimaging studies in humans show that with sustained abstinence, recovery occurs in key regions. This includes structural recovery in the prefrontal cortex, hippocampus, and cerebellum, and functional recovery of dopamine systems and other neurochemical pathways [5].

- Cognitive Restructuring: Therapies like Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT) help individuals identify and reframe maladaptive thought patterns, effectively creating new, healthier neural pathways that reduce cravings and promote positive behaviors [6].

- Lifestyle Interventions: Specific, non-pharmacological interventions can directly promote healthy neuroplasticity.

- Physical Exercise: A meta-analysis of 22 studies showed exercise increases abstinence rates, reduces withdrawal symptoms, and alleviates co-occurring anxiety and depression [3]. Exercise stimulates neurotrophic factors and improves overall brain function.

- Social Connection: Positive social interactions and support groups stimulate oxytocin release, which reduces stress and promotes feelings of safety and trust, counteracting the isolation of addiction [6].

Table 2: Research Reagents for Studying Neuroplasticity in Addiction

| Reagent / Tool | Category | Primary Function in Research |

|---|---|---|

| Viral Vectors (e.g., AAV) | Molecular Biology | Used to overexpress or knock down genes (e.g., HDAC5, Scn4b) in specific brain regions to study their function. |

| Patch-Clamp Electrophysiology | Electrophysiology | Measures changes in neuronal excitability and synaptic strength in brain slices following drug exposure or manipulation. |

| DREADDs (Designer Receptors Exclusively Activated by Designer Drugs) | Chemogenetics | Allows precise remote control of specific neuronal populations to establish causal links between circuit activity and behavior. |

| PET/CT Radioligands (e.g., for DAT) | Neuroimaging | Enables quantification of protein targets like dopamine transporters in the living human brain to track disease progression and recovery. |

| Cocaine HCL | Pharmacological | The primary reinforcer in self-administration models to study addiction-like behavior and test potential therapies. |

The evolutionary perspective provides a powerful explanatory model for the pervasive vulnerability to addiction. Our brains, optimized for an ancient world, are biologically unprepared for the potent rewards of the modern era. This "old brain in a new environment" is susceptible to hijacking by substances that mimic, with unparalleled intensity, the neurochemical signals of fitness and survival.

The path forward, however, is not one of biological determinism. Research unequivocally demonstrates that the neuroplasticity which underwrites addiction also provides the substrate for healing. The focus of modern drug development must therefore shift towards leveraging this inherent plasticity. This involves a multi-pronged strategy: targeting specific molecular pathways like the HDAC5-SCN4B axis to selectively weaken drug memories [4]; developing pharmacological aids such as GLP-1 receptor agonists that may reduce the desire for substances [2]; and formally integrating evidence-based lifestyle interventions like exercise and social support into treatment paradigms to actively promote healthy neural rewiring [3] [5].

Viewing addiction through this dual lens of evolutionary mismatch and neuroplastic potential reframes the disorder. It is not a moral failure but a predictable, albeit tragic, consequence of our biology. By developing therapies that work in concert with the brain's innate capacity for change, we can create more effective, compassionate, and enduring solutions for recovery.

The transition from voluntary drug use to compulsive addiction represents a profound dysregulation of the brain's innate reward circuitry, driven by maladaptive neuroplasticity. This whitepaper examines the exploitation of the mesolimbic pathway through dopamine-mediated reinforcement and subsequent glutamatergic restructuring that establishes persistent addiction cycles. Beyond initial dopamine surges, the addiction process involves coordinated dysregulation of stress systems, executive control networks, and synaptic remodeling processes that vary by substance class. Current research reveals that these same neuroplastic mechanisms can be harnessed for recovery through targeted behavioral and pharmacological interventions. Understanding the hierarchical recruitment of neurotransmitter systems—from initial dopamine signals to enduring glutamate-mediated structural changes—provides critical insights for developing novel treatment strategies that address the full neurobiological scope of substance use disorders.

The brain's reward system evolved as a conserved neurobiological network to reinforce behaviors essential for survival, such as eating and social bonding. Central to this system is the mesolimbic dopamine pathway, comprising dopaminergic neurons originating in the ventral tegmental area (VTA) that project to the nucleus accumbens (NAc) in the basal ganglia [7] [8]. Under natural conditions, rewarding stimuli trigger moderate dopamine release in the NAc, creating pleasure sensations and reinforcing the associated behaviors through positive reinforcement mechanisms [7].

This reward processing system operates in concert with other brain regions, including:

- Prefrontal cortex (PFC): Mediates executive control, decision-making, and impulse regulation

- Amygdala: Processes emotional salience and associates cues with rewarding experiences

- Hippocampus: Encodes contextual information related to reward experiences [7] [9]

Drugs of abuse exploit this conserved reinforcement system by triggering disproportionate dopamine signaling—up to 10 times greater than natural rewards—which establishes powerful, maladaptive learning pathways [10]. The initial neurochemical effects vary by substance class, but all converge on the final common pathway of increased dopamine in the NAc, initiating a cascade of neuroadaptations that progressively shift control from voluntary to habitual and ultimately compulsive drug use [7].

Molecular Mechanisms of Reward Exploitation

Dopamine: The Primary Reward Signal

Dopamine serves as the principal neurotransmitter in reward processing, with its release in the nucleus accumbens constituting a conserved neural signal for reinforcement across species [7]. While early models emphasized dopamine's role in mediating pleasure ("liking"), contemporary research indicates its more crucial function involves incentive salience ("wanting")—the attribution of motivational importance to reward-predicting cues [7] [9]. This distinction explains why addicted individuals compulsously seek drugs despite reporting diminished pleasure from their use.

Drugs of abuse increase dopamine through diverse initial molecular targets, as detailed in Table 1, but ultimately converge on enhanced dopamine signaling in the mesolimbic pathway [7]. With repeated drug exposure, the brain adapts through downregulation of dopamine receptors and reduced basal dopamine activity, creating a hypodopaminergic state that diminishes sensitivity to natural rewards and creates negative emotional states during withdrawal [7] [9].

Table 1: Neuropharmacological Mechanisms of Major Drug Classes

| Drug Class | Primary Molecular Targets | Effect on Dopamine Transmission | Additional Neurotransmitters Involved |

|---|---|---|---|

| Opioids | Mu opioid receptors (MOR) | ↑ DA via disinhibition of VTA GABAergic neurons | Endogenous opioids, GABA |

| Stimulants | Dopamine transporter (DAT), VMAT2 | ↑ DA via reuptake blockade or reversal of DAT | Norepinephrine, serotonin |

| Alcohol | Multiple: GABAₐ, NMDA, MOR | ↑ DA via indirect VTA activation | GABA, glutamate, endogenous opioids |

| Nicotine | Nicotinic ACh receptors (α4β2) | ↑ DA via direct activation of VTA neurons | Acetylcholine, GABA |

| Cannabis | CB1 cannabinoid receptors | ↑ or ↓ DA via GABA/glutamate modulation | Endocannabinoids, GABA, glutamate |

Beyond Dopamine: Recruitment of Additional Neurotransmitter Systems

While dopamine initiates reward reinforcement, the transition to addiction involves progressively broader neurotransmitter system recruitment:

Glutamate mediates the learned associations between drug effects and environmental contexts through synaptic plasticity in corticostriatal circuits [7]. Chronic drug use triggers homeostatic synaptic scaling that strengthens glutamatergic signaling from prefrontal regions to the NAc, establishing automatic habitual responses to drug-associated cues [7] [11].

Stress neurotransmitters, including corticotropin-releasing factor (CRF), dynorphin, and norepinephrine, become hyperactive in the extended amygdala during withdrawal, creating a persistent negative emotional state termed hyperkatifeia (heightened negative emotional state) [9]. This hypersensitivity to stress and diminished reward function drives drug seeking through negative reinforcement—using drugs to relieve distressing states rather than to experience pleasure [9].

Endogenous opioid and cannabinoid systems contribute to both the hedonic effects of drugs and the regulation of stress responses [7]. The mu opioid receptor (MOR), for instance, is essential for the rewarding properties of not just opioids but also alcohol, cocaine, and nicotine [7].

Neuroplastic Adaptations in Addiction

The Three-Stage Addiction Cycle

Addiction progresses through a recurrent cycle with distinct neurobiological substrates, as conceptualized by Koob and Volkow [9]. Each stage involves specific brain regions, neurocircuits, and neurotransmitters that become progressively dysregulated:

Binge/Intoxication Stage: Substance use activates reward circuits in the basal ganglia, with dopamine, opioid peptides, GABA, and glutamate reinforcing the drug-taking behavior and establishing incentive salience [9]. With repetition, control shifts from voluntary action to habit formation in the dorsal striatum [7] [9].

Withdrawal/Negative Affect Stage: Cessation of drug use triggers hyperactivity in brain stress systems (CRF, dynorphin) within the extended amygdala, coupled with reduced reward function (dopamine depletion) [9]. The resulting hyperkatifeia—characterized by dysphoria, anxiety, irritability, and emotional pain—drives further drug use through negative reinforcement [9].

Preoccupation/Anticipation Stage: In this stage, executive function becomes dysregulated due to disrupted prefrontal cortex activity [9]. Glutamate-mediated cravings and impaired impulse control lead to compulsive drug seeking, particularly when triggered by stress, drug-associated cues, or negative emotional states [7] [9].

Molecular Signaling Pathways in Neuroplasticity

Chronic drug exposure induces synaptic remodeling through conserved molecular pathways. The diagram below illustrates key signaling cascades involved in addiction-related neuroplasticity:

The progression from initial drug use to addiction involves hierarchical recruitment of molecular pathways:

Drug-Receptor Interactions: Specific pharmacological targets vary by substance class (Table 1), but all ultimately increase VTA dopamine neuron activity [7].

Dopamine-Glutamate Interactions: Repeated dopamine surges potentiate glutamatergic transmission from prefrontal regions to the striatum, strengthening drug-associated cue responses [7].

Neurotrophic Signaling: Chronic administration induces brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) release, activating mTOR pathway signaling that promotes synaptogenesis and structural plasticity [12] [11].

Epigenetic Modifications: Persistent changes in gene expression through chromatin remodeling and DNA methylation create stable molecular memories of addiction [7].

These coordinated molecular adaptations result in the structural and functional brain changes that characterize addiction, including prefrontal hypofunction (impaired executive control), striatal hyperfunction (enhanced habit formation), and amygdala hyperreactivity (negative emotionality) [7] [9].

Experimental Methodologies in Addiction Neuroscience

Key Research Approaches

Addiction neuroscience employs diverse methodological approaches, each with specific applications and reporting standards [13]:

Quantitative Methods:

- Experimental designs: Randomized controlled trials testing pharmacological or behavioral interventions

- Observational studies: Cohort and cross-sectional studies examining addiction prevalence, risk factors, and natural history

- Neuroimaging: fMRI, PET, and structural MRI to identify brain changes associated with addiction

- Genetic studies: Genome-wide association studies (GWAS) and gene expression analyses to identify hereditary factors

Qualitative Methods:

- In-depth interviews: Exploring subjective experiences of addiction and recovery

- Focus groups: Examining social and contextual factors influencing drug use

- Phenomenological analysis: Understanding the lived experience of addiction

Mixed-Methods Approaches: Integrating quantitative and qualitative data to provide comprehensive insights into addiction phenomena [13].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 2: Key Research Reagents and Materials in Addiction Neuroscience

| Reagent/Material | Function/Application | Example Use Cases |

|---|---|---|

| Transgenic animal models | Genetic manipulation of specific neural pathways | Studying role of dopamine receptors, opioid receptors in reward processing |

| Radioligands for PET imaging | Quantifying receptor availability and occupancy | Measuring dopamine receptor density in human addicts |

| Receptor-specific agonists/antagonists | Pharmacological dissection of neurotransmitter systems | Testing candidate medications for addiction treatment |

| Viral vector systems (AAV, lentivirus) | Targeted gene delivery to specific cell populations | Circuit-specific manipulation of gene expression |

| Electrophysiology setups | Measuring neuronal activity and synaptic plasticity | Assessing LTP/LTD in reward circuits after drug exposure |

| Behavioral testing apparatus | Modeling addiction-like behaviors in animals | Self-administration, conditioned place preference paradigms |

| CRISPR-Cas9 systems | Precise genome editing | Validating candidate addiction-related genes |

Standardized Experimental Protocols

Self-Administration Paradigm:

- Purpose: Model compulsive drug seeking and taking in animals

- Procedure: Animals are surgically implanted with intravenous catheters and trained to perform an operant response (e.g., lever press) to receive drug infusions

- Key measures: Acquisition rate, breaking point under progressive ratio schedules, resistance to punishment, relapse during extinction

- Variations: Context-induced reinstatement, cue-induced reinstatement, stress-induced reinstatement

Conditioned Place Preference (CPP):

- Purpose: Measure drug reward and associative learning

- Procedure: Animals receive drug in one distinct context and vehicle in another; preference for drug-paired context is quantified

- Key measures: Time spent in drug-paired context, extinction rate, reinstatement

Quantitative Neuroimaging Protocol:

- Purpose: Identify structural and functional brain changes in human addicts

- Procedure: Acquisition of high-resolution structural MRI, resting-state fMRI, and task-based fMRI during cue exposure or decision-making tasks

- Key measures: Gray matter volume, functional connectivity, BOLD response to drug cues, diffusion tensor imaging of white matter integrity

Electrophysiological Recording in Brain Slices:

- Purpose: Measure synaptic plasticity in reward circuits

- Procedure: Prepare acute brain slices containing VTA, NAc, or PFC; record field EPSPs or whole-cell currents before and after drug application

- Key measures: Long-term potentiation (LTP), long-term depression (LTD), miniature excitatory/inhibitory postsynaptic current frequency and amplitude

Harnessing Neuroplasticity for Recovery and Treatment

The same neuroplastic mechanisms that underlie addiction present opportunities for intervention through targeted behavioral and pharmacological approaches:

Medication-Assisted Treatment (MAT) utilizes the neuroplastic capacity of the brain to normalize function [10] [14]. Opioid agonist therapies (e.g., methadone, buprenorphine) stabilize opioid systems, while antagonist therapies (e.g., naltrexone) block the rewarding effects of drugs, allowing extinction learning to occur [10].

Behavioral Therapies leverage experience-dependent neuroplasticity to establish alternative cognitive and behavioral patterns [14]. Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT) teaches recognition and avoidance of drug-use triggers, while contingency management provides alternative reinforcement to strengthen abstinence-related behaviors [14].

Emerging Neuroplasticity-Based Interventions show promise for enhancing recovery outcomes. Psychedelic-assisted therapy using psilocybin or ketamine may promote rapid neuroplastic changes that disrupt maladaptive patterns [12]. These substances appear to stimulate BDNF-trKB signaling and mTOR-mediated synaptogenesis, potentially "resetting" addictive circuitry [12]. Neuromodulation approaches including transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS) and deep brain stimulation (DBS) directly target dysregulated circuits to restore functional balance [11].

Table 3: Neuroplasticity-Focused Treatment Approaches

| Treatment Approach | Proposed Mechanism of Action | Targeted Circuitry | Evidence Status |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cognitive Behavioral Therapy | Strengthens prefrontal top-down control; creates new learning to override drug associations | Prefrontal-striatal pathways | Strong efficacy evidence for multiple SUDs |

| Medication-Assisted Treatment | Stabilizes neurotransmitter systems; reduces reward from drug use and withdrawal severity | Dopamine, opioid, or stress systems | Gold standard for OUD and AUD |

| Contingency Management | Provides alternative reinforcement to compete with drug rewards; leverages dopamine prediction error signaling | Mesolimbic reward system | Highly effective for stimulant use disorders |

| Psychedelic-Assisted Therapy | Promotes rapid synaptogenesis; disrupts rigid patterns through altered belief systems | Cortico-striatal-thalamic circuits | Promising early results for AUD, tobacco |

| Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation | Modulates cortical excitability; enhances cognitive control and reduces craving | Prefrontal cortex projections to striatum | FDA-cleared for depression; investigational for SUD |

The exploitation of the brain's reward system in addiction represents a hierarchical recruitment of neurotransmitter pathways, beginning with dopamine-mediated reinforcement and progressing to glutamate-driven structural plasticity that establishes persistent addiction cycles. This understanding reframes addiction as a disorder of maladaptive learning and neuroplasticity, rather than simply a dopamine dysregulation syndrome.

Future research directions should focus on:

- Circuit-specific interventions that target defined neural populations rather than broad brain regions

- Personalized medicine approaches based on genetic, developmental, and environmental vulnerability factors

- Chronotherapeutic strategies that account for circadian influences on reward system function

- Combination therapies that simultaneously target multiple nodes of the addiction cycle

The expanding toolkit for investigating and manipulating neuroplastic mechanisms—from optogenetics and chemogenetics to circuit-specific neuromodulation—promises to revolutionize addiction treatment by targeting the specific neural adaptations that maintain substance use disorders. By understanding how the brain's reward system is exploited, we can develop more effective strategies to harness neuroplasticity for recovery.

Addiction is a chronic relapsing disorder characterized by a compulsion to seek and take a substance, loss of control over intake, and emergence of a negative emotional state during withdrawal [15]. Contemporary neurobiological research frames addiction as a disorder arising from pathological neuroadaptations within specific brain circuits, driven by the brain's inherent plasticity [9] [16]. The three-stage cycle—binge/intoxication, withdrawal/negative affect, and preoccupation/anticipation—provides a heuristic model for understanding how these neuroadaptations escalate and perpetuate the disorder [17] [18]. This cycle worsens over time, involving a shift from positive to negative reinforcement and from impulsive to compulsive drug use [15]. The very plasticity that allows for the development of addiction also underpins the potential for recovery, as evidenced by the brain's ability to partially reverse these changes during sustained abstinence and through targeted interventions [9] [14].

Stage 1: Binge/Intoxication

The binge/intoxication stage is defined by the pleasurable or rewarding effects of a substance, which positively reinforce its use and initiate the addiction cycle [17] [18]. This stage is primarily associated with neuroplasticity within the basal ganglia, a key node of the brain's reward circuit [16].

Core Neurocircuitry and Neurotransmitters

The rewarding effects are largely mediated by the mesolimbic dopamine pathway, which projects from the ventral tegmental area (VTA) to the nucleus accumbens (NAcc) [8]. Drugs of abuse cause a rapid and steep increase in dopamine release in the NAcc, which is critical for the subjective "high" and for triggering conditioned responses [15]. This surge preferentially stimulates low-affinity dopamine D1 receptors, which are necessary for drug reward [15]. Concurrently, other neurotransmitters contribute to the hedonic experience; for instance, alcohol activates opioid receptors in the NAcc, contributing to its pleasurable effects [9].

Key Neuroadaptive Changes

With repeated cycling, the brain undergoes significant plasticity in the basal ganglia:

- Incentive Salience: Dopamine firing patterns shift from responding to the drug itself to anticipating drug-related cues (e.g., people, places, paraphernalia) [17]. This process, known as incentive salience, attaches powerful motivational value to these cues, transforming them into potent triggers for drug seeking [9].

- Habit Formation: Control over drug-seeking behavior progressively shifts from the ventral striatum (reward) to the dorsal striatum [17] [16]. This transition from goal-directed action to habitual responding is a core component of compulsion, making the behavior automatic and difficult to suppress [9].

Table 1: Key Neurotransmitter Systems in the Binge/Intoxication Stage

| Neurotransmitter/System | Change | Primary Brain Region | Functional Role |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dopamine | Increase [15] | VTA, NAcc [8] | Reward, reinforcement, incentive salience [9] |

| Opioid Peptides | Increase [15] | NAcc [9] | Pleasure, euphoria [9] |

| GABA | Increase [15] | VTA, Basal Ganglia | Modulation of dopamine neuron activity |

| Glutamate | Increase [15] | Dorsal Striatum [15] | Habit formation and synaptic plasticity [16] |

Figure 1: Neurocircuitry of the Binge/Intoxication Stage. Substance use activates the VTA, leading to dopamine release in the NAcc and opioid peptide release within the NAcc itself. Repeated exposure drives plasticity that establishes incentive salience and shifts behavioral control to the dorsal striatum, promoting habit formation.

Stage 2: Withdrawal/Negative Affect

The withdrawal/negative affect stage emerges when drug use ceases or is reduced, leading to a pronounced negative emotional state termed hyperkatifeia (a hypersensitivity to negative emotional states) [9]. This stage is driven by a combination of reward deficits and the recruitment of brain stress systems, primarily within the extended amygdala [17] [16].

Core Neurocircuitry and Neurotransmitters

This stage is defined by two major neuroadaptations:

- Within-System Neuroadaptation: Chronic drug use leads to a hypofunctioning of the brain's reward systems. There is a decrease in dopaminergic tone in the NAcc and a shift in the glutamate-GABA balance towards increased excitatory tone, leading to diminished pleasure from the drug and from natural rewards (anhedonia) [17].

- Between-Systems Neuroadaptation: The extended amygdala, comprising the bed nucleus of the stria terminalis (BNST), central amygdala (CeA), and a part of the NAcc shell, becomes hyperactive [17] [16]. This "anti-reward" system is upregulated, leading to increased release of stress neurotransmitters [17].

Table 2: Key Neurotransmitter Systems in the Withdrawal/Negative Affect Stage

| Neurotransmitter/System | Change | Primary Brain Region | Functional Role |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dopamine | Decrease [15] | NAcc [17] | Anhedonia, low reward |

| CRF | Increase [15] | Extended Amygdala [17] | Anxiety, stress response |

| Dynorphin | Increase [15] | Extended Amygdala [17] | Dysphoria, stress |

| Norepinephrine | Increase [15] | Extended Amygdala | Anxiety, arousal |

| Neuropeptide Y | Decrease [15] | Extended Amygdala | Reduced anti-stress buffer |

| Endocannabinoids | Decrease [15] | Extended Amygdala | Reduced anti-stress buffer |

Key Neuroadaptive Changes

The plasticity in this stage manifests as a persistent change in emotional set point:

- Allostatic Load: The chronic overactivation of stress systems and underactivation of reward systems creates an allostatic state—a dysregulated emotional baseline that is lower than pre-addiction levels [16]. This state of persistent distress is a major driver of relapse via negative reinforcement, where the individual seeks the drug not for pleasure but to alleviate the misery of withdrawal [9] [17].

- Loss of Anti-Stress Buffers: Systems that normally buffer stress, such as neuropeptide Y, nociceptin, and endocannabinoids, are downregulated, further tilting the balance towards a negative emotional state [17] [15].

Figure 2: Neurocircuitry of the Withdrawal/Negative Affect Stage. Abstinence triggers a reward deficit and activates the extended amygdala, leading to a surplus of stress. The convergence of these processes produces hyperkatifeia, which motivates further drug use through negative reinforcement.

Stage 3: Preoccupation/Anticipation

The preoccupation/anticipation (or "craving") stage involves the persistent desire for the drug and a high risk of relapse, even after prolonged abstinence [15] [18]. This stage is characterized by deficits in executive function and is primarily associated with dysregulation of the prefrontal cortex (PFC) and its connections to the basal ganglia and extended amygdala [9] [16].

Core Neurocircuitry and Neurotransmitters

The PFC, responsible for executive functions like impulse control, decision-making, and emotional regulation, becomes compromised in addiction [9] [18]. Two key systems within the PFC are implicated:

- "Go" System: Involves the dorsolateral PFC and anterior cingulate, driving goal-directed behaviors. In addiction, this system may become hyperactive towards drug-seeking goals [17].

- "Stop" System: Exerts inhibitory control over impulses. This system is hypoactive in addiction, reducing the ability to resist cravings [17]. The primary neurotransmitter implicated in cravings is glutamate. Projections from the PFC to the NAcc and extended amygdala, using glutamate, can trigger intense urges to use drugs in response to cues, stress, or the drug itself [15].

Key Neuroadaptive Changes

- Executive Dysfunction: The PFC shows reduced activation, leading to poor judgment, impaired impulse control, and an inability to regulate the powerful motivational drives generated in the earlier stages of the cycle [9] [18].

- Cue-Reactivity: Environmental cues previously associated with drug use can activate a distributed network including the orbitofrontal cortex, basolateral amygdala, hippocampus, and insula, triggering intense cravings and preoccupation with drug seeking [16]. The insula, in particular, is involved in interoceptive awareness of these craving states [15].

Table 3: Key Neurotransmitter Systems in the Preoccupation/Anticipation Stage

| Neurotransmitter/System | Change | Primary Brain Region | Functional Role |

|---|---|---|---|

| Glutamate | Increase [15] | PFC to NAcc/Amygdala [15] | Craving, relapse |

| Dopamine | Increase [15] | PFC, Striatum | Motivation for drug seeking |

| Corticotropin-Releasing Factor | Increase [15] | PFC, Extended Amygdala | Stress-induced craving |

Experimental Models and Methodologies

To study the neuroplasticity underlying the addiction cycle, researchers employ a range of sophisticated animal models and experimental protocols that mirror the human condition.

Key Behavioral Paradigms

- Drug Self-Administration (Binge/Intoxication): Animals are trained to perform an operant response (e.g., pressing a lever) to receive an intravenous infusion of a drug [15] [19]. This model directly assesses the reinforcing properties of drugs. "Escalation of intake" models, where animals have extended access to the drug, are used to model the transition from controlled use to binge-like and compulsive use [16].

- Conditioned Place Preference (Binge/Intoxication): A non-operant model where one environment is paired with the drug and another with saline. The animal's subsequent preference for the drug-paired environment is used to measure the rewarding effects of the drug [19].

- Reinstatement Models (Preoccupation/Anticipation): After self-administration training and subsequent extinction of the drug-seeking behavior, the reemergence of drug seeking is triggered by: 1) a priming injection of the drug (drug-induced reinstatement), 2) exposure to drug-associated cues (cue-induced reinstatement), or 3) exposure to a stressor (stress-induced reinstatement) [15] [19]. This is a primary model for studying relapse.

- Motivational Measures of Withdrawal (Withdrawal/Negative Affect): The elevated plus maze, light-dark box, and measures of intracranial self-stimulation thresholds are used to quantify anxiety-like behavior and anhedonia during acute and protracted withdrawal [16] [19].

Neurobiological Assessment Techniques

- Chemogenetics (DREADDs) & Optogenetics: These techniques allow for the precise, reversible control of specific neuronal populations or pathways. For example, researchers can inhibit or activate glutamatergic projections from the PFC to the NAcc during a reinstatement test to determine their causal role in relapse [16].

- In Vivo Electrophysiology: This involves recording the electrical activity of neurons (e.g., in the VTA or NAcc) in behaving animals during different stages of the addiction cycle to understand how firing patterns change with addiction development [15].

- Microdialysis and Electrochemistry: These techniques are used to measure transient changes in neurotransmitter levels (e.g., dopamine, glutamate) in specific brain regions in real-time during drug intake, withdrawal, or cue exposure [15].

Table 4: Research Reagent Solutions for Studying Addiction Neurocircuitry

| Reagent / Tool | Category | Primary Function in Research |

|---|---|---|

| DREADDs (Designer Receptors Exclusively Activated by Designer Drugs) | Chemogenetics | Allows remote, reversible control of specific neuronal circuits; e.g., to inhibit a stress circuit during withdrawal. |

| Channelrhodopsin (ChR2) | Optogenetics | Allows millisecond-timescale activation of specific neurons or pathways with light; e.g., to stimulate dopamine neurons. |

| CREB Transgenic Mice | Genetic Models | Used to study the role of the transcription factor CREB in the extended amygdala in regulating negative affect. |

| Fast-Scan Cyclic Voltammetry (FSCV) | Neurochemistry | Provides real-time, second-by-second measurement of dopamine release in awake, behaving animals. |

| CX546 (AMPA Receptor Potentiator) | Pharmacological Probe | Used to test the hypothesis that potentiating glutamate signaling in the accumbens can reduce relapse. |

| CRF Receptor Antagonists | Pharmacological Probe | Used to test the role of CRF in stress-induced reinstatement and withdrawal-induced negative affect. |

Figure 3: Generalized Experimental Workflow. A typical protocol for establishing a causal link between a neural circuit and a behavior. After training an animal in a relevant paradigm, a specific circuit is manipulated during a behavioral test, and subsequent tissue analysis can reveal molecular correlates.

Implications for Therapeutic Development

The three-stage model and its underlying neuroplasticity mechanisms provide a robust framework for developing novel treatment strategies. The goal is to reverse or compensate for the specific neuroadaptations in each stage [18].

- Targeting the Binge/Intoxication Stage: Medications that block the rewarding effects of drugs (e.g., opioid receptor antagonists like naltrexone) can be effective by reducing the positive reinforcement that initiates the cycle [9]. Vaccines that generate antibodies to sequester the drug in the bloodstream, preventing it from reaching the brain, are also under investigation.

- Targeting the Withdrawal/Negative Affect Stage: A major therapeutic focus is on dampening the overactive brain stress systems. CRF receptor antagonists, nociceptin agonists, and neuropeptide Y enhancers are being explored to alleviate the negative emotional state that drives negative reinforcement [17] [15].

- Targeting the Preoccupation/Anticipation Stage: Strategies here aim to restore executive control and reduce cravings. N-acetylcysteine, which normalizes glutamatergic transmission at the cystine-glutamate exchanger, has shown promise in reducing craving and relapse in clinical trials [15]. Non-invasive brain stimulation (e.g., TMS) of the PFC is being tested to enhance cognitive control. Furthermore, behavioral therapies like Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT) and contingency management leverage neuroplasticity to help patients form new, healthier neural pathways and coping strategies [14].

The brain's inherent neuroplasticity means that these interventions, combined with sustained abstinence, can promote recovery. The reversal of drug-induced changes, such as the potential normalization of neurogenesis in the hippocampus and prefrontal cortex through exercise and environmental enrichment, represents a promising avenue for promoting long-term resilience against relapse [19] [14].

Addiction is understood as a chronic brain disorder characterized by specific neuroadaptations that fundamentally alter motivational processes and behavioral control [17] [20]. The transition from voluntary substance use to compulsive addiction represents a cascade of neuroplastic changes that reorganize brain circuits responsible for reward, motivation, and executive function [16]. This progression follows a recognizable three-stage cycle—binge/intoxication, withdrawal/negative affect, and preoccupation/anticipation—each mediated by distinct but interacting neural circuits [17] [16]. Central to this transition is the shift from incentive salience attribution, which generates pathological "wanting," to habit formation, which establishes compulsive drug-seeking behaviors that persist despite adverse consequences [21] [22]. Understanding these mechanisms provides critical insights for developing targeted interventions that address the specific neurobiological processes underlying addiction.

Neurobiological Mechanisms of Incentive Salience

Theoretical Foundations and Neural Substrates

Incentive salience is defined as a form of motivationally-charged "wanting" that is distinct from both hedonic "liking" and cognitive forms of desire [21] [23]. According to the incentive-sensitization theory, repeated drug use sensitizes mesocorticolimbic dopamine systems, resulting in pathological levels of incentive salience attribution to drugs and drug-associated stimuli [21] [22]. This neural sensitization produces compulsive drug "wanting" that can occur independently of conscious desire or even in opposition to cognitive goals [21].

The primary neural circuit for incentive salience involves mesocorticolimbic dopamine pathways originating in the ventral tegmental area (VTA) and projecting to the nucleus accumbens (NAc), with additional contributions from the amygdala, ventral pallidum, and prefrontal cortex [23] [24]. Dopamine release in this circuit, particularly phasic dopamine signaling, attributes motivational value to reward-predictive cues, making them attention-grabbing and attractive [21] [23]. Importantly, this "wanting" system is neurobiologically distinct from "liking" systems, which involve smaller hedonic hotspots in the NAc and ventral pallidum that utilize opioid and endocannabinoid signaling [21].

Molecular Mechanisms and Sensitization

At the molecular level, repeated drug exposure induces neuroadaptations that enhance dopamine reactivity to drug-associated stimuli. These include:

- Increased sensitivity of D1 receptors and reduced availability of D2 receptors in the striatum [23]

- Synaptic plasticity in medium spiny neurons of the NAc, including increased dendritic length and spine density [23]

- Enhanced glutamatergic signaling from prefrontal cortex and amygdala to the VTA and NAc, regulating dopamine neuron burst firing [23]

These changes create a hypersensitive dopamine system that responds excessively to drug cues, generating powerful motivation to seek and consume drugs [22]. Sensitization can persist long after drug cessation, contributing to the chronic relapse risk characteristic of addiction [22].

The Transition to Habitual Compulsive Use

Neurocircuitry of Habit Formation

As addiction progresses, behavioral control shifts from goal-directed actions to habitual responses mediated by different neural circuits. This transition involves a progression from ventral to dorsal striatal control [16] [24]. Early drug use primarily engages the mesolimbic pathway (VTA to NAc), which mediates the rewarding effects of substances and initial incentive salience attribution [24]. With repeated use, control shifts to the nigrostriatal pathway (substantia nigra to dorsolateral striatum), which mediates habit formation and automatic behaviors [24].

This neural reorganization is reflected in two distinct corticostriatal loops [25]:

- The associative loop (prefrontal cortex and orbitofrontal cortex to dorsomedial striatum) supports goal-directed behavior

- The sensorimotor loop (sensorimotor cortex to dorsolateral striatum) supports habitual behavior

As drug use escalates, the sensorimotor loop dominates behavioral control, leading to compulsive drug-seeking that is triggered automatically by environmental cues without regard to consequences [25].

Behavioral Manifestations of the Transition

The shift from incentive salience to habit is marked by specific behavioral changes:

- Progression from impulsive to compulsive use despite negative consequences [17]

- Reduced behavioral flexibility and persistence of drug-seeking even when rewards are devalued [25] [22]

- Context-dependent automaticity where drug-associated cues trigger drug-seeking behaviors without conscious intent [25]

This transition explains key clinical features of addiction, including the resourcefulness of addicts in obtaining drugs (incentive salience) and the ritualized patterns of drug consumption once obtained (habits) [22].

Experimental Approaches and Methodologies

Behavioral Paradigms for Measuring Incentive Salience and Habits

Table 1: Behavioral Paradigms for Studying Addiction Transitions

| Paradigm | Purpose | Key Measures | Neural Correlates |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sign-tracking vs Goal-tracking | Measures incentive salience attribution | Approach to cue (sign-tracking) vs reward location (goal-tracking) | Dopamine release in NAc; individual variation in vulnerability [23] |

| Reward Devaluation | Assesses habitual vs goal-directed behavior | Persistence of responding after reward devaluation | Dorsolateral striatum activity (habits) vs medial prefrontal cortex (goal-directed) [25] |

| Contingency Degradation | Determines action-outcome vs stimulus-response learning | Response rate when action-outcome contingency is disrupted | Shift from ventral to dorsal striatal control [25] |

| Conditioned Place Preference | Measures drug-context associations | Time spent in drug-paired context | Mesolimbic dopamine system activation [16] |

| Self-administration with Reinstatement | Models relapse behavior | Drug-seeking after extinction in response to cues, stress, or primes | Prefrontal cortex, amygdala, and dopamine system engagement [16] |

Neurobiological Assessment Techniques

Table 2: Neurobiological Methods for Studying Addiction Transitions

| Method | Application | Key Findings in Addiction |

|---|---|---|

| Fast-Scan Cyclic Voltammetry | Measures real-time dopamine dynamics | Phasic dopamine signals to drug cues; sensitized responses after repeated drug exposure [24] |

| Chemogenetics (DREADDs) | Circuit-specific manipulation | Causal roles for specific pathways; VTA-NAc circuit in incentive salience; nigrostriatal circuit in habits [24] |

| Optogenetics | Precise temporal control of neural activity | Direct activation of dopamine neurons reinforces behavior; mimics drug effects [24] |

| fMRI/PET Imaging | Human brain activity and receptor quantification | Reduced D2 receptors in striatum; enhanced reactivity to drug cues in striatum and PFC [20] [23] |

| Electrophysiology | Neuronal firing patterns | Altered firing rates and patterns in VTA and striatum after chronic drug exposure [16] |

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Addiction Neuroscience

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Research Application |

|---|---|---|

| Dopaminergic Compounds | SCH23390 (D1 antagonist), Eticlopride (D2 antagonist) | Receptor-specific manipulation of dopamine signaling; dissecting roles in "wanting" vs "liking" [23] |

| Optogenetic Tools | Channelrhodopsin (ChR2), Halorhodopsin (NpHR) | Precise temporal control of specific neuronal populations in addiction circuits [24] |

| Chemogenetic Receptors | DREADDs (Designer Receptors Exclusively Activated by Designer Drugs) | Remote control of neuronal activity in specific circuits over longer time scales [24] |

| Genetic Models | Cre-Lox system, DAT-Cre, D1-Cre, D2-Cre mice | Cell-type specific manipulation of medium spiny neurons in striatal pathways [24] |

| Sensitization Protocols | Repeated amphetamine or cocaine administration | Induction of behavioral and neural sensitization; modeling transition to addiction [22] |

| Viral Vectors | AAVs for gene delivery, Ca²⁺ indicators (GCaMP) | Circuit mapping and monitoring neuronal activity during behavior [24] |

Visualization of Neurocircuitry Transitions

Three-Stage Addiction Cycle Neurocircuitry

Transition from Goal-Directed to Habitual Behavior

Incentive Sensitization Mechanism

Implications for Therapeutic Development

Understanding the transition from incentive salience to habit formation provides critical insights for developing targeted addiction treatments. Effective interventions must address both the sensitized "wanting" driven by dopamine systems and the compulsive habits mediated by dorsal striatal circuits [23] [22]. Potential approaches include:

- Pharmacological interventions that target specific dopamine receptor subtypes to reduce cue-triggered craving without affecting natural reward processing [23]

- Cognitive training to enhance prefrontal cortical control over sensitized incentive salience and habitual responses [25]

- Cue exposure therapy to extinguish the learned associations between drug cues and motivational states [23]

- Mindfulness-based interventions that reduce activity in the subgenual anterior cingulate cortex and ventral striatum during cue exposure [23]

Future research should focus on developing circuit-specific interventions that can reverse the neuroadaptations underlying incentive sensitization and habit formation while preserving adaptive learning and motivation [24].

The transition from incentive salience to habit represents a fundamental reorganization of brain circuits that drives the development of compulsive drug use. This progression involves neuroplastic changes across multiple brain regions, beginning with sensitization of mesolimbic dopamine systems that generate pathological "wanting" for drugs and culminating in a shift to dorsal striatal control that establishes automatic, habitual drug-seeking behaviors [16] [22]. Understanding these mechanisms provides a framework for developing targeted interventions that address the specific neurobiological processes underlying different stages of addiction. Future research using increasingly precise circuit-manipulation tools will continue to elucidate these transitions, potentially identifying new opportunities for therapeutic intervention that can restore behavioral control and reduce relapse in addiction.

Addiction is a complex, chronic relapsing disorder conceptualized as a neuroplasticity-driven process involving maladaptive learning within the brain's reward circuitry [26] [14]. Vulnerability to developing a substance use disorder is not predetermined but arises from the dynamic interplay of an individual's genetic makeup and their lifetime exposure to environmental factors [27]. This interaction governs the transition from voluntary, recreational drug use to compulsive, habitual drug-seeking and taking, which is the hallmark of addiction [16]. Understanding these risk factors is paramount for researchers and drug development professionals aiming to develop targeted interventions that can bolster resilience and mitigate vulnerability. This technical guide provides an in-depth analysis of the genetic and environmental determinants of addiction, framed within the context of neuroplasticity, and details the experimental methodologies used to investigate them.

Genetic Risk Factors

Genetic predispositions account for a substantial portion of the risk for addiction, with heritability estimates explaining 40–70% of the population's variability in developing a substance use disorder [27] [8]. These genetic influences are highly polygenic, involving variations in numerous genes that affect the brain's reward, stress, and self-control systems.

Key Genetic Associations and Polymorphisms

Table 1: Key Genetic Variations Associated with Addiction Vulnerability

| Gene/Polymorphism | Function/Pathway | Associated Phenotype | Effect Size/OR (if provided) |

|---|---|---|---|

| DRD2 Taq1A (rs1800497) | Dopamine D2 Receptor Density [27] | General Addiction Vulnerability [27] | A1 allele associated with lower D2 receptor density [27] |

| Alcohol-Metabolizing Genes (e.g., ADH, ALDH) | Ethanol Metabolism [27] | Alcohol Use Disorder [27] | Not Specified |

| Serotonin Transporter Genes | Serotonergic Signaling [27] | Response to Stress, Impulsivity [27] | Not Specified |

| Dopaminergic & Opioid System Genes | Reward Processing [27] | Specific Substance Addictions [27] | Not Specified |

Genome-wide association studies (GWAS) have identified specific single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) linked to addiction. The most well-replicated finding is the A1 allele of the Taq1A polymorphism near the DRD2 gene, which codes for the dopamine D2 receptor. Individuals carrying this allele exhibit a lower density of D2 receptors in the striatum, a condition associated with a higher risk for various addictions and reduced sensitivity to natural rewards [27]. Beyond dopaminergic pathways, genes influencing the serotonergic system (e.g., serotonin transporters) are linked to impulse control, a key risk factor, while genes for alcohol-metabolizing enzymes (e.g., ADH, ALDH) significantly influence the risk for alcohol use disorder [27].

The Role of Epigenetics

Gene expression is dynamically regulated by epigenetic mechanisms, which are themselves influenced by environmental exposures. DNA methylation and histone modification are the most studied epigenetic alterations in addiction research [27]. Repeated stressful life events or drug exposure can cause stable epigenetic changes, altering the expression of genes critical for neuroplasticity and stress response without changing the underlying DNA sequence [27]. For instance, downregulation of the G9a histone methyltransferase in the nucleus accumbens has been linked to resilient phenotypes in animal models of chronic stress [27]. Furthermore, paternal and maternal experiences, such as stress, can induce epigenetic changes that are heritable and alter the offspring's hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis response to stress, thereby influencing vulnerability across generations [27].

Environmental Risk Factors

Environmental factors modulate genetic risk and can directly instigate neuroplastic changes that predispose an individual to addiction. These factors operate across the lifespan, from early childhood to adulthood.

Table 2: Environmental Risk and Resilience Factors

| Category | Risk Factors | Resilience/Protective Factors |

|---|---|---|

| Social & Early Life | Childhood Adversity [27]; Low Socioeconomic Status [27]; Parental Neglect [8] | High Parental Monitoring [27]; Higher Level of Education [27]; Strong Social Support [27] [8] |

| Psychological & Behavioral | Preexisting Mental Illness [27] [8]; High Stress [8]; Trauma/PTSD [8] | Effective Coping Styles [27]; Impulse Control [27] |

| Substance-Specific | Early Drug Exposure [27]; High Drug Availability [27] | Not Specified |

Key environmental risk factors include:

- Childhood Adversity and Stress: Exposure to trauma, neglect, or chronic stress during development is a powerful risk factor. These experiences can cause epigenetic changes and dysregulate the brain's stress and reward pathways, increasing vulnerability to drugs as a coping mechanism [27] [8].

- Social and Economic Factors: Lower levels of education, socioeconomic status, and a lack of social support are correlated with increased risk. Conversely, parental monitoring during adolescence has been shown to attenuate genetic risk, as demonstrated in twin studies on smoking [27].

- Preexisting Mental Health Conditions: Comorbid conditions such as depression, anxiety, and PTSD significantly increase vulnerability, often leading to self-medication with substances [8].

- Drug Availability and Exposure: The nature of the addictive agent itself, including its pharmacokinetics and psychoactive potency, influences its addictive potential [27].

Neurobiological Pathways and Neuroplasticity

The convergence of genetic and environmental risk factors leads to enduring neuroplastic changes in specific brain circuits, driving the transition to addiction. The disorder is characterized by a three-stage cycle—binge/intoxication, withdrawal/negative affect, and preoccupation/anticipation—each mediated by distinct but overlapping neurocircuitry [8] [16].

The Reward System and Dopaminergic Pathway

The mesolimbic dopamine pathway, originating in the ventral tegmental area (VTA) and projecting to the nucleus accumbens (NAc), is the cornerstone of the brain's reward system [27] [8]. All addictive substances directly or indirectly increase dopamine in the NAc, producing pleasure and reinforcing drug-taking behavior. With repeated use, neuroplasticity occurs: the brain adapts by reducing natural dopamine production and D2 receptor sensitivity, leading to tolerance [8] [26]. This creates a hypo-dopaminergic state where the individual no longer experiences pleasure from the drug or natural rewards, requiring more substance just to feel normal [27].

The Glutamatergic Pathway and Synaptic Plasticity

Chronic drug use profoundly disrupts glutamate homeostasis, which is critical for learning and memory. The transition from goal-directed to habitual drug-seeking involves a shift in control from the ventral to the dorsal striatum, mediated by glutamatergic projections [26] [16]. Key neuroadaptations include:

- Reduced basal glutamate levels in the NAc.

- Potentiated synaptic glutamate release during drug cue exposure.

- An increased ratio of AMPA to NMDA receptors at synapses in the NAc, stabilizing strong cue-drug associations [26]. These changes disrupt normal synaptic plasticity, such as long-term potentiation (LTP) and long-term depression (LTD), underlying the persistence of addictive memories [26].

The Stress and Executive Control Systems

The withdrawal/negative affect stage is primarily mediated by the extended amygdala and its stress neurotransmitters, such as corticotropin-releasing factor (CRF) [16]. This generates the anxiety, dysphoria, and irritability that drive negative reinforcement (using the drug to avoid withdrawal). The preoccupation/anticipation stage involves a widely distributed network including the prefrontal cortex (PFC), orbitofrontal cortex (OFC), anterior cingulate, and hippocampus [8] [16]. Addiction is associated with prefrontal hypofunction, which impairs executive functions, decision-making, and impulse control, making it difficult to resist cravings and drug-related cues [8].

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Research into the genetic and neurobiological basis of addiction relies on a combination of human studies and controlled animal models.

Key Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

| Reagent/Material | Function/Application in Research |

|---|---|

| N-acetylcysteine | A cystine prodrug used to restore glutamate homeostasis via cystine-glutamate exchange in the NAc; tested to reduce drug-seeking in animals and humans [26]. |

| Ceftriaxone | An antibiotic that upregulates glutamate transporter 1 (GLT-1), increasing glutamate uptake and shown to prevent reinstatement of drug-seeking in rodents [26]. |

| Raclopride (³H-labeled) | A radioactive dopamine D2/D3 receptor antagonist used in positron emission tomography (PET) and in vitro binding assays to quantify receptor availability and dopamine release [26]. |

| Brain-Derived Neurotrophic Factor (BDNF) Assays | ELISA and other immunoassays to measure levels of this key growth factor, which increases during incubation of craving in reward areas [26]. |

| Delta FosB Antibodies | Immunohistochemistry and Western Blotting to detect and quantify this stable transcription factor, which accumulates in the NAc and striatum after chronic drug exposure and regulates plasticity genes [26]. |

Protocol: Conditioned Place Preference (CPP)

Objective: To measure the rewarding effects of a substance by assessing the development of an association between the drug effects and a specific environment.

- Apparatus: A rectangular box divided into two or more distinct compartments with unique visual and tactile cues.

- Pre-Test: Mice/rats are allowed to freely explore the entire apparatus. The time spent in each compartment is recorded to establish a baseline preference.

- Conditioning: Over several days, animals are injected with the drug of abuse and confined to one compartment. On alternate days, they are injected with saline and confined to the other compartment.

- Post-Test: Animals are again allowed free access to all compartments while in a drug-free state. A significant increase in time spent in the drug-paired compartment compared to pre-test indicates a conditioned preference for the drug's effects.

- Reinstatement/Relapse: After extinction of the CPP, drug-seeking can be reinstated by a priming drug dose, stress, or exposure to drug-paired cues, modeling relapse.

Protocol: Operant Self-Administration and Reinstatement

Objective: To model active drug-taking and relapse in animals.

- Surgery: Rats or mice are surgically implanted with an intravenous catheter allowing for drug delivery.

- Training: In an operant chamber, animals learn to perform a response (e.g., pressing a lever) to receive an intravenous infusion of a drug (e.g., cocaine). A cue light is often paired with each infusion.

- Extinction: The drug is disconnected. Lever presses no longer result in drug or cue presentation, leading to a gradual reduction in lever-pressing behavior.

- Reinstatement Test: Following extinction, drug-seeking behavior is reinstated by one of three triggers:

- Drug-induced: A non-contingent, low-dose priming injection of the drug.

- Cue-induced: Re-presentation of the drug-paired cue light.

- Stress-induced: Exposure to a mild stressor (e.g., foot shock).

- Measurement: The number of active lever presses during the test session, in the absence of drug reward, quantifies the motivation to relapse.

Human Brain Imaging Protocols

Objective: To identify structural and functional brain changes in individuals with addiction.

- fMRI Cue-Reactivity Task:

- Stimuli: Participants are shown drug-related cues (e.g., pictures of drug paraphernalia) and neutral cues in a block design.

- Data Acquisition: Blood-oxygen-level-dependent (BOLD) signals are measured using fMRI.

- Analysis: Contrasting brain activity during drug-cue blocks vs. neutral-cue blocks identifies regions activated by craving (e.g., amygdala, dorsal striatum, OFC). Connectivity analyses can reveal circuit-level dysfunctions [26].

- PET with [¹¹C]Raclopride:

- Tracer Injection: The radioligand [¹¹C]Raclopride, which binds to D2/D3 receptors, is administered intravenously.

- Baseline Scan: A PET scan is performed to measure baseline D2/D3 receptor availability.

- Challenge Scan: After administration of a stimulant drug (e.g., methylphenidate) or exposure to drug cues, a second scan is performed. The stimulant-induced dopamine release competes with raclopride for receptors, leading to a reduction in binding potential. This displacement quantifies the magnitude of dopamine release in the striatum [26].

Implications for Intervention and Future Research

The neuroplasticity framework of addiction suggests that recovery is possible by harnessing the brain's inherent capacity for change. Evidence-based behavioral therapies like Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT) and contingency management work by promoting new learning and strengthening prefrontal inhibitory control, thereby creating new, resilient neural pathways to compete with drug-seeking ones [8] [14]. Pharmacological approaches aim to correct underlying neurobiological deficits, such as using N-acetylcysteine to restore glutamate homeostasis or medications to manage withdrawal and craving [26].

Future research should focus on:

- Developing personalized medicine approaches based on an individual's unique genetic and epigenetic profile.

- Novel therapeutics that directly target the stable neuroplastic changes underlying addictive memories (e.g., by erasing or reconsolidating them).

- Leveraging advanced technologies like real-time fMRI neurofeedback and non-invasive brain stimulation (TMS, tDCS) to directly modulate dysfunctional circuits and enhance resilience [26] [28].

Harnessing Plasticity: Methodological Advances and Therapeutic Applications

Neuroplasticity, the brain's fundamental capacity to reorganize its structure and function in response to experience, represents a critical biological process in both the development of and recovery from substance use disorders (SUDs). The same neural adaptability that makes the brain susceptible to addiction also enables it to heal, particularly when internal and external conditions support recovery [5]. Research from the National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA) has demonstrated that prolonged abstinence from drugs like methamphetamine allows for the recovery of lost dopamine transporters in the striatum, while longitudinal neuroimaging studies show structural and functional recovery in frontal cortical regions, hippocampus, and cerebellum during sustained remission [5]. As individuals learn new behaviors, goals, and rewards, this learning process reshapes synaptic connectivity across neural circuits, ultimately outcompeting drug-related memories and automatic behavioral patterns that weaken over time [5]. High-content imaging platforms provide the technological bridge to quantitatively measure these neuroplastic changes at the cellular level, offering unprecedented insights into the mechanisms of addiction and recovery for researchers and drug development professionals.

High-Content Imaging Technology Platforms

Core Principles and Terminology

High-content screening (HCS) integrates automated multicolor fluorescence imaging with quantitative data analysis to simultaneously evaluate multiple molecular features in individual cells [29]. This approach differs from traditional microscopy by capturing hundreds to millions of cellular images, thereby generating robust datasets with statistical power far exceeding conventional methods [29]. The terminology in this field includes:

- High-Content Imaging (HCI): Refers to the underlying automated image-based high-throughput technology used to measure and monitor phenotypic changes [29].

- High-Content Screening (HCS): Applies HCI to screen hundreds to millions of compounds to identify new drug targets and hits in complex cellular systems, including 3D cultures [29].

- High-Content Analysis (HCA): Utilizes multiparameter algorithms to extract detailed cellular physiology profiles from HCS data, enabling complex analyses of cell populations [29].

Leading Platform Specifications

Thermo Fisher Scientific offers some of the most widely cited HCA instruments in scientific literature, including the ArrayScan High-Content Platforms, CellInsight CX5 High-Content Screening Platform, and the recently introduced CellInsight CX7 High-Content Analysis Platform [30]. These platforms provide the resolution of microscopy combined with statistical power inherent in quantitative analysis of large cell numbers. The CellInsight CX7 HCA Platform represents an integrated benchtop instrument that interrogates multiple sample types with a wide range of techniques, leveraging advanced image acquisition and analysis software [30]. These systems build on a 20-year legacy of HCA instrument development and over 40 years of fluorescence imaging and probe development, making them particularly suitable for neuroplasticity research requiring precise quantification of subtle morphological changes [30].

Table 1: Comparison of High-Content Analysis Platforms

| Platform | Key Features | Applications in Neuroplasticity Research | Analysis Software |

|---|---|---|---|

| CellInsight CX7 HCA Platform | Integrated benchtop design, confocal acquisition, multiple sample type interrogation | Neurite outgrowth, synaptic connectivity, neural cell differentiation | HCS Studio with specialized bioapplications |

| CellInsight CX5 HCS Platform | High-content screening capabilities, temperature and CO₂ control | Cell health parameters, oxidative stress, protein synthesis/degradation | HCS Studio Cell Analysis Software |

| ArrayScan Platforms | High-resolution imaging, live-cell capabilities, temperature control | Mitochondrial function, lysosomal activity, neural progenitor proliferation | HCS Studio with customizable algorithms |

| CellInsight NXT Platform | Advanced automation compatibility, high-speed imaging | Neural progenitor proliferation, synaptic puncta counting | HCS Studio with machine learning options |

Quantitative Phenotypic Screening for Neuroplasticity

Neurite Outgrowth as a Key Metric

Sygnature Discovery has developed a semi-automated high-content imaging platform that specifically quantifies neurite outgrowth across PC12, SH-SY5Y, and primary neuron models [31]. This robust, scalable tool enables phenotypic screening of neuroplasticity modulators, accelerating the identification of new therapies for neuropsychiatric and neurodegenerative disorders [31]. The platform measures multiple parameters of neurite development, including total outgrowth length, branching complexity, and process diameter, which serve as quantitative indicators of structural neuroplasticity. These measurements provide crucial data on a compound's ability to promote neural connectivity, a fundamental process compromised in addiction and essential for recovery.

Recent research has leveraged these approaches to investigate specific molecular pathways. For instance, studies using the ArrayScan XTI High-Content Platform have demonstrated that Nrf2 nuclear translocation in response to rotenone treatment correlates with neurite retraction in neural stem cells derived from human induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) [30]. Similarly, Hill et al. utilized the CellInsight NXT High-Content Screening Platform to study how mutations in the transcription factor gene TCF4 affect human cortical cell progenitor proliferation, with implications for cognitive deficits found in Pitt-Hopkins syndrome [30].

Synaptogenesis Screening Applications

A groundbreaking application of high-content imaging in neuroplasticity research involves optical pooled screening to investigate synapse formation. A recent study published in Cell Reports employed high-throughput single-cell optical pooled screening to analyze over two million single-cell phenotypic profiles, identifying 102 candidate regulators of neuroligin-1 linked to cell adhesion, cytoskeletal dynamics, and signaling [32]. Among these, researchers demonstrated that the phosphatase PTEN and the dystrophin-associated glycoprotein DAG1 promote neuroligin's roles in inducing presynaptic assembly, with DAG1 selectively regulating inhibitory synapses [32]. This work establishes a scalable high-content screening approach for cell-cell interactions that enables systematic studies of the molecular interactions guiding synaptogenesis, a crucial process underlying the neural rewiring that occurs during recovery from addiction.

Table 2: Key Quantitative Parameters in Neuroplasticity Screening

| Parameter Category | Specific Measurements | Biological Significance | Research Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Neurite Morphology | Total outgrowth length, number of branches, branch points, average process diameter | Indicators of structural connectivity and neural network formation | Screening neurotrophic compounds, assessing developmental neurotoxicity |

| Synaptic Density | Puncta count per neurite, synaptic protein clustering, colocalization of pre- and postsynaptic markers | Functional connectivity and information processing capacity | Studying synaptogenesis mechanisms, evaluating cognitive enhancers |

| Cell Body Morphology | Nuclear size, cytoplasmic volume, organelle distribution | Cellular health and metabolic activity | Neuroprotection studies, cytotoxicity assessment |

| Mitochondrial Function | Membrane potential, ROS production, distribution along neurites | Energy supply for plasticity processes and oxidative stress status | Investigating metabolic aspects of addiction and recovery |

Experimental Protocols for Neuroplasticity Assessment

Neurite Outgrowth Protocol

A standardized protocol for assessing neurite outgrowth using high-content imaging platforms involves several critical steps:

Cell Model Selection: Choose appropriate cellular models based on research objectives. Common models include:

- PC12 cells (rat pheochromocytoma) - Responsive to NGF-induced differentiation