Neurobiological Mechanisms of Addiction Relapse Vulnerability: From Neural Circuits to Clinical Biomarkers

This article synthesizes current research on the neurobiological underpinnings of addiction relapse vulnerability, addressing the needs of researchers and drug development professionals.

Neurobiological Mechanisms of Addiction Relapse Vulnerability: From Neural Circuits to Clinical Biomarkers

Abstract

This article synthesizes current research on the neurobiological underpinnings of addiction relapse vulnerability, addressing the needs of researchers and drug development professionals. It explores the foundational neural circuits and neuroadaptations in the binge/intoxication, withdrawal/negative affect, and preoccupation/anticipation stages of addiction. The content details methodological approaches for identifying biomarkers, including neuroimaging and stress response measures, and investigates troubleshooting strategies for high-relapse-risk populations by targeting immune and stress systems. Finally, it validates and compares predictive models and emerging pharmacological targets, providing a comprehensive resource for developing novel, mechanism-based relapse prevention therapies.

Core Neurocircuitry and Lasting Neuroadaptations in Relapse Vulnerability

Addiction is a chronically relapsing disorder characterized by a compulsive cycle of drug seeking and taking, loss of control over intake, and emergence of a negative emotional state during withdrawal [1] [2]. The contemporary understanding of addiction has evolved from historical conceptualizations of moral failure to a medical model based on well-defined neurobiological mechanisms [3] [4]. This transition in understanding is supported by extensive evidence showing that addiction produces dramatic, long-lasting changes in brain function that reduce an individual's ability to control substance use [4]. The three-stage cycle of addiction—binge/intoxication, withdrawal/negative affect, and preoccupation/anticipation—provides a heuristic framework for investigating the neurobiological underpinnings of relapse vulnerability [3] [1] [5]. This cycle worsens over time, involves neuroplastic changes in brain reward, stress, and executive function systems, and creates a self-perpetuating mechanism that drives relapse even after prolonged abstinence [5] [2]. The delineation of this cycle has transformed research approaches, shifting focus from acute drug effects to the chronic neuroadaptations that underlie the transition from controlled use to addiction and persistent relapse vulnerability [1] [4].

The Binge/Intoxication Stage: Neural Substrates of Reward and Habit Formation

The binge/intoxication stage is primarily mediated by the basal ganglia, with key roles for the nucleus accumbens (ventral striatum) and dorsal striatum [3] [5] [6]. During this stage, all addictive substances directly or indirectly increase dopamine transmission in the nucleus accumbens, producing the rewarding effects that positively reinforce drug use [3] [7]. The mesolimbic dopamine pathway, originating in the ventral tegmental area (VTA) and projecting to the nucleus accumbens, serves as a common neural substrate for the acute rewarding effects of all major classes of addictive drugs [1] [5]. Stimulant drugs such as amphetamines and cocaine directly increase dopaminergic transmission, whereas opioids, alcohol, and nicotine indirectly facilitate dopamine release by inhibiting GABAergic interneurons in the VTA, thereby disinhibiting dopamine neurons [7].

As addiction progresses, a fundamental neurobiological shift occurs from voluntary drug use to habitual and ultimately compulsive drug seeking [1] [5]. This transition involves a transfer of behavioral control from the ventral to the dorsal striatum, particularly strengthening the nigrostriatal pathway that controls habitual motor function and behavior [3]. This neural reorganization underlies the development of incentive salience, whereby drug-associated cues (people, places, paraphernalia) themselves begin to elicit dopamine release and motivate drug-seeking behavior, even before the drug is consumed [3] [1]. This phenomenon helps explain the powerful role of conditioned cues in triggering relapse [3].

Table 1: Key Neurotransmitter Systems in the Binge/Intoxication Stage

| Neurotransmitter/Neuromodulator | Direction of Change | Primary Brain Regions | Functional Consequences |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dopamine | Increase [5] | Ventral striatum, dorsal striatum [3] | Reward, reinforcement, habit formation [3] |

| Opioid peptides | Increase [5] | Nucleus accumbens, VTA [6] | Pleasure, reward enhancement [6] |

| GABA | Increase [5] | VTA, nucleus accumbens [7] | Modulation of dopamine neuron activity [7] |

| Endocannabinoids | Increase [7] | VTA, nucleus accumbens [7] | Modulation of reward signaling [7] |

The Withdrawal/Negative Affect Stage: Recruitment of Brain Stress Systems

The withdrawal/negative affect stage is characterized by the emergence of a negative emotional state—including dysphoria, anxiety, irritability, and physical discomfort—when drug use is discontinued [3] [1]. This stage primarily involves the extended amygdala, a macrostructure comprising the bed nucleus of the stria terminalis (BNST), central nucleus of the amygdala (CeA), and a transition zone in the medial portion of the nucleus accumbens (shell) [3] [5]. This stage represents a critical shift in the motivation for drug use from positive reinforcement (seeking pleasure) to negative reinforcement (seeking relief from discomfort) [1] [2].

Two major neuroadaptations characterize this stage: within-system changes in reward circuitry and between-system recruitment of brain stress systems [3]. Chronic drug exposure leads to a decrease in dopaminergic tone in the nucleus accumbens and a shift in the glutamatergic-GABAergic balance toward increased glutamatergic tone, resulting in diminished euphoria from the drug, reduced tolerance for stress, and decreased responsiveness to natural rewards [3]. Simultaneously, the brain's "anti-reward" system becomes upregulated, leading to increased release of stress mediators including corticotropin-releasing factor (CRF), dynorphin, norepinephrine, and orexin (hypocretin), with concomitant positive modulation of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis [3] [5].

The brain possesses inherent buffer systems to counterbalance this anti-reward system, including cannabinoid (CB1), nociceptin, and neuropeptide Y neurotransmission [3]. alterations in these buffering systems may further increase addiction vulnerability, as evidenced by findings of decreased CB1 receptor density in individuals with alcohol use disorder [3]. The clinical manifestation of these neuroadaptations includes irritability, anxiety, dysphoria, and a general state of psychological and physical distress that powerfully motivates renewed drug use through negative reinforcement mechanisms [3] [1].

Table 2: Key Neurotransmitter Systems in the Withdrawal/Negative Affect Stage

| Neurotransmitter/Neuromodulator | Direction of Change | Primary Brain Regions | Functional Consequences |

|---|---|---|---|

| Corticotropin-releasing factor (CRF) | Increase [5] | Extended amygdala [5] | Stress response, anxiety [3] |

| Dynorphin | Increase [5] | Extended amygdala [5] | Dysphoria, aversive state [5] |

| Norepinephrine | Increase [5] | Extended amygdala [5] | Arousal, stress response [3] |

| Dopamine | Decrease [5] | Nucleus accumbens [3] | Anhedonia, reduced reward [3] |

| Endocannabinoids | Decrease [5] | Extended amygdala [3] | Reduced buffering of stress [3] |

| Neuropeptide Y | Decrease [5] | Extended amygdala [3] | Reduced buffering of stress [3] |

The Preoccupation/Anticipation Stage: Neural Circuits of Craving and Executive Dysfunction

The preoccupation/anticipation stage, characterized by intense craving and loss of cognitive control over drug seeking, primarily involves the prefrontal cortex (PFC) and its connections with the basal ganglia and extended amygdala [3] [5] [2]. This stage represents a critical domain of executive function that includes the ability to organize thoughts and activities, prioritize tasks, manage time, make decisions, and regulate emotions and impulses [4]. In addiction, these regulatory capacities become compromised, leading to the intense preoccupation with drug seeking and diminished ability to resist urges that characterize craving [3] [2].

Researchers have conceptualized two systems within the PFC that contribute to this stage: a "Go system" and a "Stop system" [3]. The Go system, involving the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex and anterior cingulate, is responsible for attention and planning of goal-directed behaviors, including drug seeking [3]. The Stop system is critical for inhibitory control and the ability to suppress maladaptive behaviors such as drug use [3]. In addiction, the balance between these systems becomes disrupted, with hyperactivity in the Go system combined with hypoactivity in the Stop system, resulting in compulsivity and impaired impulse control [3] [5].

The neurochemistry of this stage involves increased glutamatergic transmission from the prefrontal cortex to the nucleus accumbens and other reward-related regions, which drives drug-seeking behavior [5]. Additionally, dopamine, CRF, and orexin systems contribute to the craving state [5]. The persistent vulnerability to relapse characteristic of addiction is thought to stem from long-lasting neuroadaptations in these prefrontal circuits that endure long after acute withdrawal has subsided [4]. Human imaging studies have consistently shown that individuals with substance use disorders exhibit reduced activity in the prefrontal regions responsible for executive control, combined with heightened responsivity of reward and emotional circuits to drug-related cues [2] [4].

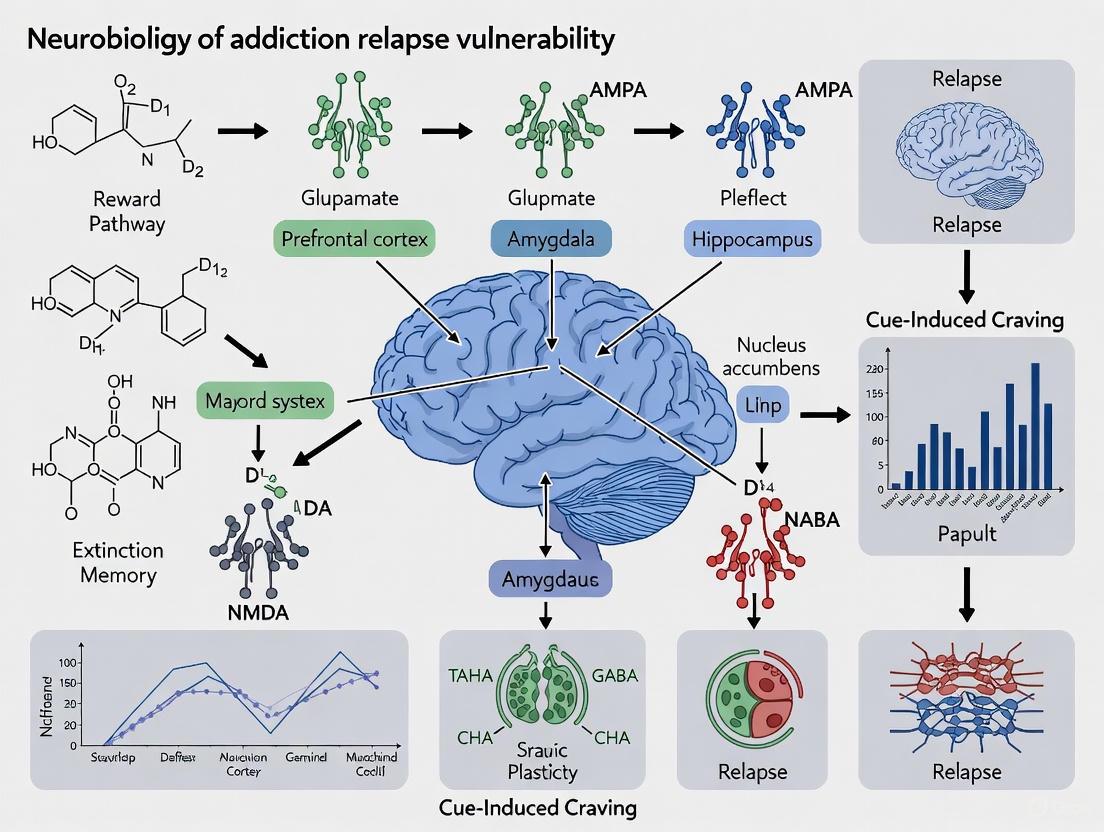

Figure 1: Neural circuitry of the preoccupation/anticipation stage of addiction

Molecular and Cellular Mechanisms of Relapse Vulnerability

The transition through the addiction cycle produces enduring molecular and cellular adaptations that create persistent relapse vulnerability. Key among these adaptations are changes in transcription factors, signaling molecules, and synaptic plasticity mechanisms that alter neural circuit function [5] [7]. Chronic exposure to drugs of abuse induces ΔFosB accumulation in the nucleus accumbens, a transcription factor that promotes increased behavioral responses to drugs and enhances dendritic arborization, potentially strengthening drug-related memories and cues [7]. Conversely, reductions in CREB (cAMP response element-binding protein) in the nucleus accumbens similarly increase behavioral responses to drugs [7].

The brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) system plays a complex role in relapse vulnerability. As BDNF accumulates, it appears to increase the incubation period of relapse [7]. Additionally, chronic drug exposure produces hyperresponsiveness of the CRF system through increased CREB-mediated gene function, leading to heightened stress reactivity [7]. The hypofrontality observed in addiction involves molecular changes including increased CREB and a shift from dopamine D2 to D1 receptor prevalence mediated by increased expression of ASG3 and cystine-glutamate transporters, contributing to impulsivity and compulsivity [7].

At the synaptic level, drugs of abuse induce long-term potentiation (LTP) in the VTA-nucleus accumbens system, creating persistent hypersensitization to drugs and drug-associated cues [7]. This includes increased expression of glutamate receptor subunit GluR1 in the VTA, increased tyrosine hydroxylase (the rate-limiting enzyme in dopamine synthesis), and alterations in intracellular signaling cascades [7]. These molecular and cellular adaptations collectively create a brain state characterized by heightened sensitivity to drugs and cues, reduced sensitivity to natural rewards, compromised stress regulation, and impaired executive control—establishing a biological basis for persistent relapse vulnerability that can endure for years after drug cessation [5] [4].

Experimental Approaches and Methodologies

Animal Models of the Addiction Cycle

Animal models have been indispensable for elucidating the neurobiological mechanisms underlying the three-stage addiction cycle [1] [5]. These models permit investigations of specific behavioral and neurobiological phenomena under highly controlled conditions that would be impossible or unethical to replicate in humans [4]. Modern animal models take advantage of individual and strain diversity in drug responses, incorporate complex environments with access to alternative reinforcers, and test effects of stressful stimuli, allowing investigation of neurobiological processes underlying addiction risk and environmental resilience factors [5]. These models have been developed to specifically capture features of the binge/intoxication stage (e.g., drug self-administration), withdrawal/negative affect stage (e.g., intracranial self-stimulation thresholds), and preoccupation/anticipation stage (e.g., cue-induced reinstatement of drug seeking) [1].

Human Neuroimaging Studies

Human neuroimaging studies, particularly using functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) and positron emission tomography (PET), have provided critical insights into the human brain alterations associated with addiction and relapse [8] [4]. Resting-state fMRI (rs-fMRI) measures such as regional homogeneity (ReHo) and fractional amplitude of low-frequency fluctuation (fALFF) have proven effective in characterizing localized neural activity alterations associated with addiction [8]. These approaches allow researchers to identify functional abnormalities in specific brain regions and circuits that correlate with relapse vulnerability.

A recent longitudinal study investigating methamphetamine relapse utilized rs-fMRI to compare brain activity in abstinent methamphetamine-dependent individuals (MADIs) who subsequently relapsed, the same individuals after relapse, and healthy controls [8]. The study collected MRI data using a 3.0 Tesla Siemens scanner with T1-weighted structural parameters (repetition time TR = 1900ms; echo time TE = 2.48ms; flip angle FA = 9°; field of view FOV = 250×250mm; slice thickness = 1mm) and rs-fMRI parameters (TR/TE = 3000/40ms; FA = 90°; FOV = 240×240mm; slice thickness = 4mm; volumes = 133) [8]. Data preprocessing was conducted using Data Processing and Analysis for Brain Imaging (DPABI) software in MATLAB, including format conversion, removal of initial time points, slice timing, realignment, T1 reorientation, brain extraction, segmentation, and normalization [8]. Participants with head motion exceeding 2.0mm or rotation greater than 2.0° were excluded to minimize motion artifacts [8].

This study found that MADIs at Stage I (abstinence) demonstrated decreased brain activity in cortical regions and increased activity in subcortical regions, particularly the bilateral putamen [8]. After relapse (Stage II), individuals exhibited more widespread abnormalities, with decreased activity in the middle cingulate gyrus, parietal and occipital regions, and increased activity in subcortical regions (striatum, thalamus, hippocampal structure) and several prefrontal regions [8]. Importantly, fALFF values in the left and right caudate nucleus were negatively associated with duration of relapse, suggesting that increased activity in these regions might be associated with early relapse in abstinent individuals [8].

Figure 2: Experimental workflow for neuroimaging study of relapse prediction

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Tools for Investigating the Addiction Cycle

| Research Tool Category | Specific Examples | Research Applications |

|---|---|---|

| Animal Models | Rat/mouse self-administration [1] [5], Conditioned place preference [1], Behavioral sensitization [1] | Modeling specific stages of addiction cycle, Investigating neuroadaptations, Testing pharmacological treatments |

| Genetic Manipulation Tools | Knockout/knockin models [5] [7], CRISPR-Cas9 systems [5], RNA interference techniques [5] | Identifying gene functions in addiction vulnerability, Studying molecular mechanisms, Validating drug targets |

| Neuroimaging Approaches | Functional MRI (fMRI) [8] [4], Positron emission tomography (PET) [4], Regional homogeneity (ReHo) [8], fractional ALFF (fALFF) [8] | Mapping brain activity changes in humans, Identifying relapse predictors, Tracking treatment effects |

| Neurochemical Assays | Microdialysis [1], Fast-scan cyclic voltammetry [1], Receptor autoradiography [1] | Measuring neurotransmitter dynamics, Assessing receptor changes, Characterizing drug effects |

| Molecular Biology Reagents | Antibodies for ΔFosB, CREB, BDNF [7], PCR assays for gene expression [7], Protein quantification kits [7] | Quantifying molecular adaptations, Measuring signaling pathway changes, Assessing neuroplasticity |

Implications for Therapeutic Development and Future Research

The three-stage model provides a comprehensive neurobiological framework for developing targeted interventions for substance use disorders [3] [5]. By identifying specific neural circuits, neurotransmitters, and molecular mechanisms involved in each stage, this model enables a more precise approach to medication development [5] [4]. For example, medications targeting the binge/intoxication stage might focus on blocking the rewarding effects of drugs or mitigating the development of incentive salience, while interventions for the withdrawal/negative affect stage could aim to normalize stress system dysregulation and restore hedonic balance [3] [5]. Treatments addressing the preoccupation/anticipation stage might focus on enhancing prefrontal cortical function to improve executive control and reduce craving [3] [2].

Future research directions should include further delineation of the molecular and cellular adaptations that persist during extended abstinence, investigation of individual differences in vulnerability to addiction, exploration of developmental influences (particularly adolescence as a critical risk period), and examination of gender differences in addiction neurobiology [5] [4]. Additionally, research is needed to understand the neurobiological mechanisms underlying the high comorbidity between substance use disorders and other psychiatric conditions [4]. The continued integration of animal and human studies, leveraging increasingly sophisticated technologies and methodologies, will be essential for translating this knowledge into more effective prevention and treatment strategies for substance use disorders [4].

Addiction is a chronic relapsing disorder characterized by compulsive drug seeking despite adverse consequences, rooted in specific neurobiological adaptations. The brain's dopamine systems, particularly those governing incentive salience, undergo profound changes during the transition from casual drug use to addiction. The mesolimbic dopamine pathway, originating in the ventral tegmental area (VTA) and projecting to the nucleus accumbens (NAc), is fundamentally implicated in reward processing, motivation, and reinforcement learning [9]. Drugs of abuse commandeer this evolutionary conserved system, artificially stimulating dopamine release at magnitudes far exceeding those produced by natural rewards [9]. This surfeit triggers a cascade of neuroadaptations that ultimately result in a hypodopaminergic state, characterized by blunted reward circuit responsiveness and a heightened vulnerability to relapse [10].

The concept of incentive salience explains how drugs transform neutral environmental stimuli into potent cues that trigger overwhelming craving. Dopamine does not merely encode pleasure ("liking") but assigns motivational significance ("wanting") to reward-predictive cues [10]. In addiction, this process becomes pathologically skewed, whereby drug-associated cues garner excessive incentive salience, dominating attentional resources and motivating drug-seeking behavior, even when the drug itself is no longer pleasurable [9]. This review examines the neurobiological mechanisms through which dopamine systems and incentive salience processes are hijacked, creating a persistent state of relapse vulnerability.

Neurobiological Mechanisms of Hijacked Incentive Salience

Dopamine Signaling Alterations in Addiction

Chronic drug use induces significant and persistent alterations in dopamine neurotransmission, which underlie the core symptoms of addiction.

- Acute Drug Effects: Different classes of drugs converge on the common pathway of increasing dopamine concentrations in the NAc, though through distinct mechanisms [9]. Psychostimulants like cocaine and amphetamine directly target dopamine transmission: cocaine blocks the dopamine reuptake transporter (DAT), prolonging dopamine presence in the synaptic cleft, while amphetamine increases dopamine release and blocks reuptake [9]. Opioids, conversely, indirectly increase dopamine release by inhibiting GABAergic interneurons in the VTA, thus disinhibiting dopamine neurons [9].

- Chronic Adaptations: With repeated drug exposure, the dopamine system undergoes compensatory changes. These include decreased baseline dopamine levels, reduced dopamine receptor density (particularly D2 receptors), and diminished dopamine receptor sensitivity [9] [10]. This leads to a functional dopamine deficit in the reward circuit, manifesting clinically as anhedonia (inability to feel pleasure from natural rewards) and increased drug-seeking to restore dopamine levels [10].

- Incentive Salience and Prediction Error: Dopamine neurons code for reward prediction error (RPE)—the difference between expected and actual reward [9]. An unexpected reward triggers a phasic dopamine burst, promoting learning. Drugs of abuse cause a massive, unexpected dopamine release, creating a powerful learning signal that solidifies drug-taking behavior. Over time, as drug use becomes predictable, dopamine responses shift to the drug-predictive cues themselves [9]. This is the neural basis of cue-triggered craving; the cues themselves acquire excessive incentive salience, driving compulsive drug-seeking.

Table 1: Dopamine System Alterations in Addiction

| Phase | Dopamine Signaling | Receptor Changes | Behavioral Manifestation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Acute Use | Strong increase in NAc dopamine; magnitude exceeds natural rewards [9] | Transient activation of D1 and D2 receptors [9] | Intense euphoria ("high"); reinforcement of drug-taking action |

| Chronic Use | Decreased baseline dopamine levels; blunted phasic responses [9] [10] | Downregulation and reduced sensitivity of D2 receptors in the striatum [9] [10] | Anhedonia; tolerance; escalation of drug intake |

| Cue Exposure | Dopamine response shifts from drug to drug-predictive cues [9] | Altered signaling in cue-processing pathways [9] | Intense craving; compulsive drug-seeking triggered by cues |

Neuroadaptations, Allostasis, and Relapse Vulnerability

The chronic dysregulation of the dopamine system is part of a broader pattern of allostatic neuroadaptations—persistent changes in brain reward and stress systems that maintain stability at a pathological set-point [9] [11].

- Molecular and Structural Plasticity: Long-term drug use induces neuroplastic changes in the dopamine system and associated circuits. This includes altered gene expression, such as the accumulation of the transcription factor ΔFosB, and synaptic remodeling, like changes in dendritic spine density in the NAc and prefrontal cortex [9]. These changes underlie the long-lasting nature of addiction and the persistence of relapse vulnerability.

- Beyond Dopamine: The Anti-Reward System: The allostatic model of addiction posits that chronic drug use not only dysregates reward circuits (dopamine) but also engages a coordinated "anti-reward" system involving the extended amygdala [11]. This system, which includes the central amygdala (CeA) and bed nucleus of the stria terminalis (BNST), is rich in stress neurotransmitters like corticotropin-releasing factor (CRF) and dynorphin. Its activation produces negative emotional states (dysphoria, anxiety, irritability), especially during withdrawal. The HPA axis and glucocorticoids are also dysregulated, further fueling the stress and negative affect that drives relapse via negative reinforcement [11].

- Emotional Dysregulation as a Relapse Driver: A critical driver of relapse is emotional dysregulation during the withdrawal/negative affect stage [12]. Neuroimaging studies reveal that individuals with substance dependence show altered brain responses to negative emotional stimuli in regions like the amygdala, insula, anterior cingulate cortex (ACC), and medial prefrontal cortex (mPFC) [12]. For example, alcohol dependence is often associated with blunted activation to negative affective stimuli, while cocaine dependence shows heightened activation. This dysregulation in negative emotional processing is a key contributor to the chronic relapsing nature of addiction [12].

Table 2: Key Neuroadaptations Contributing to Relapse Vulnerability

| Adaptation Type | Key Brain Regions/Systems | Neurochemical/Neural Changes | Contribution to Relapse |

|---|---|---|---|

| Allostatic Reward | Mesolimbic Dopamine Pathway, NAc | Reduced baseline dopamine, D2 receptor downregulation [9] [10] | Anhedonia; drug seeking to relieve dopamine deficit |

| Stress System Engagement | Extended Amygdala, HPA Axis | Increased CRF, Dynorphin; Glucocorticoid dysregulation [11] | Negative emotional state (hyperkatifeia); anxiety and dysphoria [12] |

| Executive Function Deficit | Prefrontal Cortex (PFC) | Hypoactivity in dorsolateral PFC, anterior cingulate [9] [11] | Loss of impulse control; impaired decision-making; craving |

| Synaptic Remodeling | NAc, PFC | Altered gene expression (e.g., ΔFosB), changes in dendritic spines [9] | Long-term persistence of addictive behaviors and cue-reactivity |

Experimental Approaches and Methodologies

Probing Dopamine and Policy Learning in Behavioral Models

Recent research utilizing precise behavioral tracking in mice has provided evidence that mesolimbic dopamine regulates the rate of learning from action—a process central to how drug-seeking habits are formed.

Experimental Protocol:

- Subject & Preparation: Naive, head-restrained mice are acclimated to head fixation without prior behavioral shaping [13].

- Behavioral Paradigm: Mice are trained in a classical trace conditioning paradigm. An auditory cue (0.5-s tone) is presented, followed by a 1-s delay, after which a sweetened water reward is delivered irrespective of the animal's behavior [13].

- Data Acquisition: A comprehensive dataset of orofacial and body movements is collected using an accelerometer and high-resolution video to infer lick rate, whisking, pupil diameter, and nose motion [13].

- Analysis of Learning: Behavioral policies are analyzed by measuring two dissociable components: preparatory behavior (activity during the delay period) and reactive behavior (latency to initiate movement following reward delivery). The evolution of these policies is tracked as mice learn to minimize reward collection latency [13].

- Dopamine Manipulation & Measurement: Fiber photometry is used to record dopamine neuron activity in the VTA continuously throughout learning. In separate experiments, closed-loop optogenetic manipulations of VTA dopamine neurons are performed, calibrated to physiological signals, to test causal roles [13].

Key Findings: This approach demonstrated that individual differences in initial phasic dopamine responses correlated with the emergence of a learned behavioral policy, but not with value encoding for a predictive cue. Manipulations of mesolimbic dopamine produced effects consistent with it setting an adaptive learning rate for direct policy learning, rather than solely providing a reward prediction error signal [13]. This expands dopamine's role beyond value learning to directly shaping how actions are optimized, a critical mechanism in the development of compulsive drug-seeking policies.

Investigating Emotional Dysregulation in Human Addiction

Functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) is used to characterize emotional dysregulation, a critical driver of relapse, in individuals with substance dependence.

Experimental Protocol:

- Participant Groups: Individuals with alcohol, cocaine, opioid, or cannabis dependence (typically during early abstinence or treatment) are compared with matched healthy controls [12].

- fMRI Tasks:

- Facial Emotion Processing: Participants view images of emotional faces (e.g., fearful, angry, sad) and neutral faces while undergoing fMRI. They may be asked to identify the emotion or passively view the images [12].

- Aversive Stimuli Exposure: Participants are exposed to generally aversive images (e.g., from the International Affective Picture System) or to individualized stressful experience cues (script-guided imagery of personal stressful events) [12].

- Emotion Regulation: Active tasks where participants are instructed to employ conscious strategies, such as reappraisal, to regulate their emotional response to negative images [12].

- Data Analysis: Blood-oxygen-level-dependent (BOLD) responses are compared between groups and task conditions. Key regions of interest include the amygdala, insula, ACC, and mPFC. Functional connectivity between these regions may also be analyzed [12].

Key Findings: This methodology has revealed substance-specific patterns of emotional dysregulation. For instance, individuals with alcohol dependence often show blunted activation in the ACC, insula, and amygdala in response to negative emotional stimuli. Conversely, those with cocaine dependence may show heightened activation in these regions [12]. These neural response patterns are associated with clinical outcomes, such as treatment success and relapse vulnerability.

Diagram 1: Hijacked dopamine pathway in addiction.

Diagram 2: Relapse vulnerability pathways.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents and Models

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Methodologies

| Reagent / Model / Method | Function / Purpose in Addiction Research |

|---|---|

| Fibre Photometry | A technique for recording neural activity in real-time, used to measure calcium or neurotransmitter dynamics (e.g., dopamine) in specific brain circuits like the VTA-NAc pathway during behavior [13]. |

| Optogenetics | Allows for precise, millisecond-timescale control of specific neuronal populations (e.g., VTA dopamine neurons) using light, enabling causal tests of their role in drug-related behaviors and learning [13]. |

| fMRI with Emotional Tasks | Used in human subjects to map brain reactivity and functional connectivity during emotional processing, revealing dysregulation in amygdala, insula, and PFC circuits associated with relapse risk [12]. |

| Trace Conditioning Paradigm | A behavioral task used in rodents to dissociate the learning of preparatory and reactive behavioral policies, allowing investigation of how dopamine regulates the rate of learning from action [13]. |

| White Matter Neurotransmitter Atlas | A novel MRI-based atlas mapping neurotransmitter circuits (dopamine, acetylcholine, etc.) in white matter, enabling investigation of how lesions or diseases disrupt neurochemical balance and cognitive function [14]. |

| Self-Administration Model | The gold-standard rodent model of addiction, where animals perform an operant response (e.g., pressing a lever) to receive an intravenous drug infusion, modeling human drug-taking and relapse [9]. |

| Mathematical Models of Relapse | Computational models (e.g., using Ornstein-Uhlenbeck and Poisson processes) that incorporate psychological concepts to predict how life events and cues influence relapse probability [15]. |

The hijacking of dopamine systems and the consequent pathological attribution of incentive salience to drug cues create a powerful engine for addiction maintenance and relapse. The transition from controlled use to compulsive drug-seeking is mediated by a cascade of allostatic neuroadaptations that produce a chronic dopamine deficit, engange stress systems, and impair prefrontal control. The interplay between this hijacked reward pathway and emotional dysregulation forms a core mechanism of relapse vulnerability.

Future research must continue to integrate findings across scales, from molecular and cellular adaptations to circuit-level dysfunction and individual behavioral phenotypes. Promising avenues include:

- Further elucidating the role of dopamine in direct policy learning and how this process becomes rigid and habit-like in addiction [13].

- Developing a more precise characterization of emotional dysregulation subtypes across different substance use disorders to inform targeted neuromodulation therapies [12].

- Leveraging computational psychiatry approaches and human neurotransmitter atlases to create personalized models of relapse risk and novel treatment interventions [15] [14].

Addressing the multifaceted neurobiology of addiction, with the hijacked dopamine system at its core, is paramount for developing effective therapeutic strategies that can prevent relapse and promote long-term recovery.

Drug addiction is conceptualized as a chronic, relapsing disorder characterized by a compulsion to seek and take drugs, loss of control over intake, and emergence of a negative emotional state (e.g., dysphoria, anxiety, irritability) when access to the drug is prevented. This negative emotional state reflects what has been termed motivational withdrawal and forms a core component of addiction [16]. The disorder progresses through a three-stage cycle (binging/intoxication, withdrawal/negative affect, and preoccupation/anticipation) that intensifies over time and shifts from positive reinforcement to negative reinforcement mechanisms [3].

The anti-reward system represents a conceptual framework for understanding the neurobiological basis of the negative emotional state in addiction. This system is based on the hypothesis that the brain contains counter-adaptive mechanisms that oppose reward signaling, termed "anti-reward" systems [16] [17]. While reward systems are activated by acute drug administration, chronic drug use leads to recruitment of anti-reward systems that drive aversive states. The neuroanatomical substrate for this anti-reward system is primarily located within the extended amygdala, which plays a key role in the negative reinforcement that perpetuates addictive behavior [16] [3].

Table 1: Key Characteristics of Reward vs. Anti-Reward Systems in Addiction

| Feature | Reward System | Anti-Reward System |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Function | Mediates positive reinforcement | Mediates negative reinforcement |

| Dominant Neurotransmitters | Dopamine, opioid peptides, GABA | CRF, norepinephrine, dynorphin |

| Key Brain Regions | Ventral striatum, nucleus accumbens, ventral tegmental area | Extended amygdala (BNST, CeA, NAcc shell) |

| Temporal Activation | Early stage addiction | Late stage addiction |

| Behavioral Manifestation | Drug seeking for positive effects | Drug seeking to relieve negative affect |

Neuroanatomy of the Extended Amygdala

Structural Components

The extended amygdala is composed of several interconnected structures that share certain cytoarchitectural and circuitry similarities [16]. The primary components include:

- Bed nucleus of the stria terminalis (BNST): Serves as a crucial interface between the amygdala and hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis, playing a key role in stress and anxiety responses [3].

- Central nucleus of the amygdala (CeA): Functions as a principal output nucleus of the amygdala complex and is critically involved in physiological responses to stressors and drug-related stimuli [18].

- Transition zone in the medial subregion of the nucleus accumbens (shell of the NAcc): Represents a bridge between reward and stress systems, integrating motivational information [16].

This macrostructure receives abundant afferents from limbic structures such as the basolateral amygdala and hippocampus, and sends efferents to the medial part of the ventral pallidum and lateral hypothalamus, thereby interfacing classical limbic (emotional) structures with the extrapyramidal motor system [16].

Functional Neurocircuitry

The extended amygdala operates as an integrated functional unit despite its spatially separate components. It represents a critical point of convergence for sensory information from cortical and subcortical regions, enabling it to assess the emotional and motivational significance of stimuli [18]. The basolateral amygdala has a particularly important role in mediating the motivational effects of stimuli previously paired with drug seeking and drug motivational withdrawal, serving as a key node for emotional memories in general [16].

The functional connectivity of the extended amygdala is illustrated in the following diagram, which shows the primary input and output pathways:

Figure 1: Extended Amygdala Neural Circuitry

Neurochemical Substrates of the Anti-Reward System

Primary Neurotransmitter Systems

The neurochemical basis of anti-reward function within the extended amygdala involves several key neurotransmitter systems that are recruited during chronic drug exposure, producing aversive or stress-like states during withdrawal [16]:

- Corticotropin-releasing factor (CRF): Serves as a primary mediator of stress responses, with increased signaling in the extended amygdala during drug withdrawal [16] [3].

- Norepinephrine (NE): Contributes to arousal, anxiety, and stress responses, with enhanced release during withdrawal states [16].

- Dynorphin: An endogenous opioid that acts on kappa-opioid receptors to produce dysphoric effects, opposing the rewarding effects of mu-opioid receptor activation [3] [19].

These neurochemical systems form a complex, buffered system for maintaining hedonic homeostasis. Their activation creates a powerful negative emotional state that drives negative reinforcement – drug seeking to alleviate the aversive state [16].

Signaling Pathways and Neuroadaptations

Chronic drug use induces significant neuroadaptations in extended amygdala circuitry through both "within-system" and "between-system" adaptations. Within-system adaptations involve disruption of the same neurochemical systems implicated in the positive reinforcing effects of drugs, while between-system adaptations engage different neurochemical systems in an attempt to overcome the chronic presence of the drug and restore normal function [16].

The following diagram illustrates the key neurochemical signaling pathways in the anti-reward system:

Figure 2: Anti-Reward System Neurochemical Pathways

Table 2: Neurochemical Systems in the Extended Amygdala Anti-Reward System

| Neurotransmitter | Receptor Targets | Functional Role in Addiction | Direction of Change in Withdrawal |

|---|---|---|---|

| Corticotropin-releasing factor (CRF) | CRF₁, CRF₂ | Mediates stress-like responses | Increased |

| Norepinephrine | α₁, α₂, β adrenoceptors | Contributes to anxiety and arousal | Increased |

| Dynorphin | κ-opioid receptor | Produces dysphoria and aversion | Increased |

| Dopamine | D₁, D₂ receptors | Reward processing | Decreased in NAcc |

| GABA | GABAₐ, GABAᴃ | Inhibitory control | Dysregulated |

| Serotonin | 5-HT₁ʙ, 5-HT₂ᴀ | Mood regulation | Dysregulated |

Methodological Approaches for Studying Extended Amygdala Function

Experimental Models and Behavioral Paradigms

Research on the extended amygdala and anti-reward systems employs several well-validated experimental approaches:

- Intracranial self-stimulation (ICSS) threshold measurement: Used to assess brain reward function, with increased thresholds (decreased reward) observed during drug withdrawal [16]. This provides a direct operational measure of the reward deficit state associated with drug withdrawal.

- Social defeat stress models: Employed to study the contribution of stress on drug-taking and reinforcement, serving as a method of "behavioral sensitization" to drugs of abuse [20]. This model has been particularly valuable for understanding how non-pharmacological stressors exacerbate negative affective states.

- Self-administration with extended access: Animal models that use intermittent extended access to drug self-administration lead to increased motivation for drug-taking and more accurately model the transition to addiction [20].

Neurobiological Assessment Techniques

Modern neuroscience employs multiple approaches to investigate extended amygdala function in addiction:

- Circuit-mapping approaches: Rabies virus-mediated circuit mapping reveals drug-induced changes in functional connectivity, such as the persistent elevation in spontaneous and task-related activity of inhibitory GABAergic cells from the BNST to downstream targets after cocaine exposure [21].

- Chemogenetics and optogenetics: Allow precise control of specific neural populations to establish causal relationships between circuit activity and behavior [21].

- Fiber photometry: Enables real-time monitoring of neural activity in specific pathways during behavior [21].

- Neuroimaging: Human imaging studies of addicts during withdrawal or protracted abstinence have shown decreased dopamine D2 receptors and hypoactivity of the orbitofrontal-infralimbic cortex system [16].

Table 3: Key Experimental Approaches in Extended Amygdala Research

| Methodology | Application | Key Measured Parameters |

|---|---|---|

| Fiber Photometry | Real-time neural activity monitoring | Calcium signals as proxy for neuronal activity |

| Rabies Virus Circuit Mapping | Neural connectivity mapping | Monosynaptic inputs to specific cell populations |

| Chemogenetics (DREADDs) | Targeted neuronal manipulation | Behavioral changes following receptor activation |

| Microdialysis | Neurochemical measurement | Extracellular neurotransmitter levels |

| Operant Self-Administration | Addiction-like behavior measurement | Drug intake, motivation, relapse susceptibility |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents for Extended Amygdala Studies

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Research Application |

|---|---|---|

| Viral Vector Tools | AAV-DREADDs, RV-ΔG-tdTomato | Circuit manipulation and mapping |

| Cell-Type Specific Markers | GABA antibodies, c-Fos antibodies | Identification of activated neuronal populations |

| Neurochemical Assays | CRF ELISA, CORT RIA | Quantification of stress mediators |

| Receptor Ligands | CRF antagonists, κ-opioid agonists | Pharmacological dissection of systems |

| Genetic Models | CRF receptor knockout mice | Determination of molecular mechanisms |

Experimental Protocols for Key Findings

Protocol 1: Assessing CRF Dependency in Withdrawal-Induced Anxiety

This protocol is adapted from studies establishing the role of CRF in the extended amygdala in negative affect during drug withdrawal [16]:

- Subjects: Laboratory rats (n=10-12/group) with chronic catheter implantation for drug self-administration

- Drug self-administration phase:

- 2-hour daily sessions for 5-7 days to establish stable baseline

- Transition to 6-12 hour extended access sessions for 10-14 days

- Withdrawal phase:

- 24-72 hours after last drug session

- Behavioral testing in elevated plus maze or light-dark box

- Pharmacological manipulation:

- Bilateral microinjection of CRF receptor antagonists (e.g., antalarmin) into BNST or CeA

- Control groups receive vehicle injections

- Outcome measures:

- Time spent in open arms of elevated plus maze

- Plasma corticosterone levels via radioimmunoassay

- c-Fos immunohistochemistry in extended amygdala subregions

Protocol 2: Circuit-Specific Manipulation of BNST→VTA Pathway

This protocol is based on recent work defining the role of specific extended amygdala projections in addiction-related behaviors [21]:

- Viral vector delivery:

- Inject AAV-Cre into VTA of DAT-Cre mice

- Inject CAV-FLEX-TVA-mCherry into amygdala

- Inject RV-ΔG-GFP into VTA 3 weeks later

- Cell-type specific manipulation:

- Express DREADDs (hM4Di) in BNSTGABA→VTA projection neurons

- Administer CNO (clozapine-N-oxide) prior to behavioral testing

- Behavioral assessment:

- Cocaine-induced place preference conditioning

- Anxiety measures during protracted withdrawal (14-28 days)

- Reinstatement testing following extinction

- Neural activity recording:

- Fiber photometry in VTADA→amygdala cells during behavioral tests

- Measure calcium transients as indicator of neuronal activity

Clinical Implications and Translation

The extended amygdala and anti-reward system framework has significant implications for understanding and treating addiction. Human imaging studies have consistently shown abnormalities in extended amygdala regions in individuals with substance use disorders [16] [3]. The Addictions Neuroclinical Assessment (ANA) developed by the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism translates the three neurobiological stages of addiction into three neurofunctional domains: incentive salience, negative emotionality, and executive dysfunction [3]. This instrument allows clinicians to employ targeted treatments for specific clinical presentations.

The recognition that negative emotional states drive relapse through negative reinforcement mechanisms has shifted therapeutic approaches toward addressing the emotional components of addiction rather than solely focusing on reward. Pharmacotherapeutic strategies that target components of the anti-reward system, particularly CRF and kappa-opioid receptors, show promise for preventing relapse [16] [19].

The extended amygdala serves as a critical neural substrate for negative affect in addiction, functioning as the anatomical basis for the anti-reward system. Through complex neuroadaptations involving CRF, norepinephrine, and dynorphin systems, this region mediates the negative emotional state that defines motivational withdrawal and drives negative reinforcement. Understanding these mechanisms provides a neurobiological framework for developing targeted interventions for addiction that address not only the initial rewarding effects of drugs but also the negative emotional state that perpetuates the addiction cycle. Future research focusing on specific circuit elements within the extended amygdala and their interactions with other reward and stress systems holds promise for advancing addiction treatment strategies.

The preoccupation/anticipation stage of addiction, commonly known as the craving stage, is a critical phase of the addiction cycle that plays a fundamental role in relapse vulnerability [5] [2]. Unlike earlier stages dominated by acute intoxication and withdrawal, this stage is characterized by a persistent desire for the drug and a profound deficit in executive control over drug-seeking behaviors, despite periods of abstinence [5]. Research over the past two decades has established that these clinical phenomena are underpinned by significant dysfunction within the prefrontal cortex (PFC) and its distributed networks [22] [23] [24]. The Impaired Response Inhibition and Salience Attribution (iRISA) model provides a key framework for understanding this dysfunction, positing that addiction is characterized by the assignment of excessive salience to drug-related cues at the expense of non-drug rewards, coupled with a chronic inability to inhibit maladaptive behaviors [22] [24]. This whitepaper synthesizes current neurobiological evidence, detailing the specific PFC subregions involved, their functional roles, and the resulting cognitive deficits that create a perfect storm of relapse vulnerability during the preoccupation stage. Furthermore, it outlines critical experimental methodologies and reagents driving this field of research, providing a comprehensive resource for scientists and drug development professionals.

Neurobiological Basis of PFC Dysfunction

Key Prefrontal Cortex Subregions and Their Roles

The PFC is not a monolithic entity; distinct subregions contribute uniquely to the symptomatology of the preoccupation stage through their specialized roles in cognition, emotion, and motivation [22] [25]. Chronic drug use disrupts the delicate functional balance across these regions.

Table 1: PFC Subregions and Their Dysfunction in Addiction's Preoccupation Stage

| PFC Subregion | Primary Functions | Manifestation of Dysfunction in Addiction |

|---|---|---|

| Dorsolateral PFC (DLPFC) | Working memory, attention regulation, cognitive flexibility [22] [24] | Impaired working memory biased towards drug cues; inflexible attention and difficulty shifting goals away from drug procurement [22] |

| Anterior Cingulate Cortex (ACC) | Error detection, conflict monitoring, emotional regulation [22] [24] [25] | Compromised self-monitoring, failure to detect conflict between drug-seeking and other goals, and heightened stress reactivity [22] |

| Orbitofrontal Cortex (OFC) | Value representation, outcome expectation, reversal learning [22] [24] | Inability to update the value of non-drug reinforcers; choice of immediate drug reward over delayed gratification [22] |

| Ventromedial PFC (vmPFC) | Emotional regulation, decision-making, value coding [22] [24] | Enhanced motivation for drugs with decreased motivation for other goals; poor decision-making despite adverse consequences [22] |

| Ventrolateral PFC (vlPFC)/ Inferior Frontal Gyrus (IFG) | Response inhibition, impulse control [22] [24] | Core impulsivity and inability to suppress prepotent drug-seeking responses [22] |

Structural and Functional Neuroimaging Evidence

Converging evidence from human neuroimaging studies robustly demonstrates that addiction is associated with significant structural and functional alterations within the PFC.

Structural Findings: A consistent pattern of lower gray matter volume is observed across multiple substance use disorders (including tobacco, alcohol, stimulants, and opioids) compared to non-addicted controls [24]. This atrophy is particularly prominent in the OFC and vmPFC, but also extends to the DLPFC, ACC, and IFG/vlPFC [24]. Crucially, these structural deficits often have a dose-response relationship, where a longer duration of drug use correlates with lower PFC gray matter volume [24]. Evidence also suggests that these changes are not entirely permanent. Longitudinal studies indicate that abstinence can lead to a partial recovery of PFC gray matter volume, which parallels improvements in cognitive function [24].

Functional Findings: Functional MRI (fMRI) and PET studies reveal a characteristic pattern of neurofunctional dysregulation. During cue-induced craving tasks, there is a hyperactivation of the OFC and ACC in response to drug-related cues, signaling the excessive salience attributed to these stimuli [22] [2]. Concurrently, there is a hypoactivation of the DLPFC and vlPFC/IFG during tasks requiring inhibitory control or decision-making, reflecting the compromised executive control that defines the iRISA syndrome [22] [23]. This imbalance between a hyperactive "go" system (OFC/ACC) and a hypoactive "stop" system (DLPFC/vlPFC) creates a neural environment highly permissive to relapse [22].

The following diagram illustrates the key neurocircuitry involved in the preoccupation stage, highlighting the imbalance between salience attribution and inhibitory control networks:

Core Deficits: Executive Dysfunction and Craving

The neurobiological alterations described above manifest behaviorally as two core, interlinked deficits: impaired executive control and intrusive craving.

Erosion of Executive Control

Executive functions mediated by the PFC are essential for maintaining abstinence. In the preoccupation stage, a generalized deficit in inhibitory control is evident. The vlPFC/IFG, critical for suppressing prepotent responses, is hypoactive, rendering individuals unable to resist drug-seeking impulses even when they are consciously trying to abstain [22] [24]. This is compounded by deficits in decision-making, largely governed by the OFC and vmPFC. Individuals with addiction display a pronounced bias toward immediate rewards (drug use) despite delayed severe negative consequences, a pattern known as delay discounting [22] [25]. Furthermore, impaired flexibility from DLPFC and ACC dysfunction makes it difficult to shift behavioral strategies away from drug-seeking habits and toward alternative, healthy rewards [22].

Neurocognitive Drivers of Craving

Craving is more than a simple feeling; it is a complex cognitive and emotional state driven by dysregulated neural circuits. The attentional bias toward drug-related cues is a key component. Drug cues automatically capture attention, a process linked to hyperactivation of the ACC and OFC, which assign them excessive incentive salience [22] [2]. This creates a feedback loop where cues trigger craving, and craving further enhances attention to cues. The dysfunctional reward valuation by the OFC and vmPFC means that the expected value of the drug is inflated, while the value of natural reinforcers (e.g., food, social interaction) is diminished [22] [24]. This skewed value system ensures that drug-seeking remains the dominant motivational priority during the preoccupation stage.

Experimental Approaches and Methodologies

Research into PFC dysfunction in addiction relies on a multidisciplinary approach, integrating neuroimaging, neuropsychological testing, and experimental paradigms.

Key Behavioral and Cognitive Paradigms

Well-validated experimental tasks are used to probe specific cognitive functions linked to PFC subregions.

- Cue-Reactivity Paradigms: Participants are exposed to drug-related cues (e.g., pictures, paraphernalia) versus neutral cues while undergoing fMRI. Primary Outcome: Heightened BOLD response in the OFC, ACC, and striatum, correlated with self-reported craving [22] [2]. This measures the "salience attribution" component of iRISA.

- Go/No-Go and Stop-Signal Tasks: These tasks measure response inhibition. In a Go/No-Go task, participants must suppress a preponent response to a "No-Go" stimulus. The Stop-Signal Task involves stopping an already-initiated motor response. Primary Outcome: Increased error rates on inhibition trials and associated hypoactivation in the vlPFC and DLPFC in addicted individuals [22] [24]. This directly assesses the "response inhibition" deficit.

- Delay Discounting Tasks: Participants make choices between a small immediate monetary reward and a larger delayed reward. Primary Outcome: Steeper discounting of delayed rewards (i.e., greater impulsivity) is a robust marker of addiction and is associated with reduced activation in the OFC and vmPFC during choice deliberation [25].

- Iowa Gambling Task and Other Decision-Making Tasks: These tasks simulate real-world decision-making under uncertainty, requiring participants to learn from rewards and punishments. Primary Outcome: Addicted individuals consistently make disadvantageous choices, linked to OFC/vmPFC dysfunction [24].

Neuroimaging and Neurophysiological Protocols

- Structural MRI (sMRI):

- Protocol: High-resolution T1-weighted imaging.

- Analysis: Voxel-Based Morphometry (VBM) or cortical thickness analysis to quantify gray matter volume/density.

- Outcome: Identification of regional atrophy (e.g., in OFC, ACC) in addiction [24].

- Functional MRI (fMRI):

- Protocol: BOLD imaging during performance of cognitive tasks (e.g., those listed above) or at rest (resting-state fMRI).

- Analysis: General Linear Model (GLM) for task-based activation; seed-based correlation or Independent Component Analysis (ICA) for resting-state functional connectivity.

- Outcome: Maps of task-related hyper-/hypoactivation and altered functional connectivity within PFC networks (e.g., between PFC and striatum) [22] [23].

- Positron Emission Tomography (PET):

- Protocol: Administration of radioligands for specific neuroreceptors (e.g., [¹¹C]raclopride for dopamine D2/D3 receptors) or for glucose metabolism ([¹⁸F]FDG).

- Analysis: Binding potential or metabolic rate quantification.

- Outcome: Measurement of neurotransmitter system dysfunction (e.g., reduced D2 receptor availability in PFC) in addiction [5] [2].

The following diagram outlines a typical integrated experimental workflow for investigating PFC function in addiction:

Advancing research in this field requires a suite of specialized reagents, tools, and technologies.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Resources for Investigating PFC in Addiction

| Category / Item | Specific Examples | Research Function and Application |

|---|---|---|

| Neuroimaging Ligands | [¹¹C]raclopride, [¹¹C]FLB-457 | PET radioligands for quantifying dopamine D2/D3 receptor availability in the striatum and extrastriatal regions like PFC [5]. |

| Task-Based fMRI Paradigms | Stop-Signal Task, Monetary Incentive Delay Task, Cue-Reactivity Task | Standardized experimental protocols to reliably evoke and measure specific cognitive processes (inhibition, reward anticipation, craving) and their neural correlates [22] [24]. |

| Structural Analysis Pipelines | Freesurfer, CAT12 (for SPM) | Software tools for automated, precise quantification of cortical thickness and subcortical volume from T1-weighted MRI scans [24]. |

| Genetic & Molecular Kits | DNA microarrays, RNA-seq kits, PCR kits | For identifying genetic polymorphisms (e.g., in dopamine receptor genes) or transcriptional changes associated with addiction vulnerability and PFC function [5] [26]. |

| Neuromodulation Tools | Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation (TMS), tDCS kits | Non-invasive brain stimulation devices to experimentally modulate (inhibit or excite) PFC activity, testing causal roles in craving and cognitive control [23]. |

Implications for Research and Therapeutic Development

The delineation of PFC dysfunction as a core mechanism in the preoccupation stage provides a heuristic framework for developing novel treatment strategies. The evidence of neuroplasticity and partial recovery with abstinence offers a positive outlook and a target for interventions [24]. Treatments aimed at strengthening PFC-mediated inhibitory control are of paramount interest. This includes cognitive remediation therapies designed to train specific executive functions, as well as neuromodulation techniques like Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation (TMS) targeting the DLPFC or IFG to enhance their activity and restore top-down control [23] [24]. Furthermore, the neurocircuitry understanding emphasizes the need for pharmacotherapies that can rebalance the dopamine and glutamate signaling between the PFC, striatum, and extended amygdala to dampen craving and facilitate cognitive control [5] [2]. Future research must continue to leverage cross-species models [23] [24] and longitudinal designs to disentangle pre-existing vulnerabilities from drug-induced effects, ultimately paving the way for personalized and more effective interventions for addiction.

The neurobiological framework for understanding addiction relapse has traditionally centered on neuronal dysfunction. However, emerging research reveals that the brain's immune cells, particularly microglia and astrocytes, drive relapse vulnerability through previously unrecognized mechanisms. This whitepaper synthesizes recent advances demonstrating how neuroimmune interactions after drug exposure create lasting neural circuit alterations that promote drug-seeking behavior. We detail specific signaling pathways, experimental methodologies, and quantitative findings that establish neuroimmune processes as fundamental components of addiction pathology. The evidence compellingly indicates that targeting neuroimmune signaling represents a novel therapeutic frontier for developing innovative treatments for substance use disorders, moving beyond conventional neurotransmitter-focused approaches to address the persistent relapse risk that characterizes addiction.

Addiction is a chronic, relapsing brain disorder characterized by compulsive drug-seeking despite negative consequences. Traditional research has focused on neuronal adaptations within reward circuits, including the basal ganglia, extended amygdala, and prefrontal cortex [4]. The dominant model posits that addiction progresses through a three-stage cycle—binge/intoxication, withdrawal/negative affect, and preoccupation/anticipation—each involving specific neuronal networks [27]. While this framework has proven valuable, it fails to fully explain the persistent vulnerability to relapse that characterizes substance use disorders (SUDs), with over 60% of individuals treated for SUD experiencing relapse within the first year after treatment [4].

A transformative perspective has emerged with the recognition that neuroimmune mechanisms represent a critical, underappreciated component of addiction neurobiology. Drugs of abuse activate the brain's resident immune cells, initiating cascades of inflammatory signaling that directly modulate synaptic function and neural plasticity [28] [29]. This whitepaper examines how microglia, the CNS's primary immune cells, and their interactions with other glial cells and neurons, create lasting changes that drive relapse vulnerability. We synthesize evidence from recent preclinical studies that identify specific neuroimmune pathways as promising targets for innovative pharmacotherapies aimed at sustaining recovery.

Core Neuroimmune Mechanisms in Addiction Pathology

Microglial Activation and Synaptic Remodeling

Microglia, the resident immune cells of the central nervous system, continuously survey the brain microenvironment and actively participate in synaptic refinement. During abstinence from drugs of abuse, microglia undergo functional changes that significantly impact neural circuits:

- Synaptic Pruning: A groundbreaking study at UNC Chapel Hill demonstrated that during abstinence from cocaine, microglia actively prune parts of astrocytes, critical support cells that help maintain neural circuit balance. This pruning event increases drug-seeking behavior, and when blocked, reduces relapse behaviors [30].

- Regional Specificity: Microglia-induced TNFα release depresses excitatory synaptic activity within the ventral striatum through internalization of AMPARs, a process associated with cocaine-induced locomotor sensitization [28] [31].

- Complement-Mediated Phagocytosis: Microglia can eliminate synapses through complement system signaling, particularly in the developing brain, and evidence suggests similar mechanisms may contribute to drug-induced circuit reorganization [32].

Astrocyte-Microglia Crosstalk in Relapse Vulnerability

Astrocytes and microglia engage in bidirectional communication that profoundly influences neuronal function and addiction-related behaviors:

- Glutamate Dysregulation: Chronic drug use disrupts glutamate homeostasis, particularly in the nucleus accumbens. Astrocytes normally regulate extracellular glutamate levels via glutamate transporters (GLT-1 and system xc-). Drug-induced neuroimmune activation impairs this function, leading to glutamate overflow that promotes compulsive drug-seeking [29].

- Inflammatory Feedforward Loops: Activated microglia release pro-inflammatory cytokines (e.g., IL-1β, IL-6, TNFα) that trigger reactive astrogliosis. These reactive astrocytes further amplify neuroimmune signaling, creating a persistent inflammatory state that maintains addiction-related neural adaptations [29] [33].

Cytokine Modulation of Synaptic Plasticity

Cytokines, traditionally associated with peripheral immune function, are critically involved in regulating synaptic strength and plasticity in reward circuits:

Table 1: Cytokine Effects on Synaptic Plasticity in Addiction-Relevant Brain Regions

| Cytokine | Brain Region | Effect on Plasticity | Behavioral Correlation |

|---|---|---|---|

| TNFα | Hippocampus | Facilitates membrane insertion of CP-AMPARs; enhances excitatory transmission | Contextual associations in drug-seeking |

| TNFα | Striatum | Internalizes CP-AMPARs; reduces corticostriatal synaptic strength | Cocaine-induced locomotor sensitization |

| IL-6 | Hippocampus | Inhibits long-term potentiation (LTP) through MAPK/ERK signaling | Impairs hippocampus-dependent memory tasks |

| IL-1β | Hippocampus | Low concentrations enhance learning; chronic overexpression impairs LTP | Modulates fear conditioning and spatial learning |

The effects of cytokines on synaptic function are concentration-dependent and brain region-specific, creating a complex regulatory landscape that varies across different stages of addiction [28] [31].

Signaling Pathways and Molecular Mechanisms

NF-κB Pathway in Drug-Seeking Behavior

The nuclear factor-kappa B (NF-κB) pathway has emerged as a critical signaling cascade linking drug exposure to persistent neural adaptations:

The NF-κB pathway represents a promising target for pharmacotherapeutic intervention, as its inhibition may disrupt the cycle of drug-induced neuroimmune activation that maintains relapse vulnerability [29].

Neuron-Glia Communication in Reward Circuits

The interactions between neurons and glial cells within reward pathways create a complex signaling network that undergoes specific adaptations following chronic drug use:

This neuron-glia communication network demonstrates how drug-induced neuroimmune activation creates a self-reinforcing cycle that maintains elevated extracellular glutamate and promotes drug-seeking behavior [29] [31].

Quantitative Evidence from Preclinical Studies

Key Experimental Findings

Recent preclinical investigations have yielded quantitative data establishing causal relationships between neuroimmune activation and relapse behaviors:

Table 2: Quantitative Evidence of Neuroimmune Mechanisms in Addiction Models

| Experimental Manipulation | Drug Model | Key Finding | Effect Size/Quantitative Measure |

|---|---|---|---|

| Microglial inhibition (minocycline) | Cocaine | Reduced drug-seeking behavior | ~40-60% decrease in reinstatement |

| Astrocyte pruning blockade | Cocaine | Attenuated relapse behaviors | Significant reduction in cocaine-seeking |

| TNFα neutralization | Psychostimulants | Decreased locomotor sensitization | Altered AMPAR trafficking in striatum |

| TLR4 antagonist administration | Alcohol, Opioids | Reduced self-administration | Decreased motivation in operant tasks |

| NF-κB pathway inhibition | Multiple drugs | Attenuated conditioned place preference | Disrupted drug-context associations |

These quantitative findings from rigorous preclinical studies provide compelling evidence that targeting specific neuroimmune pathways can produce measurable reductions in addiction-related behaviors [30] [28] [29].

Methodological Approaches and Experimental Protocols

Assessing Microglial Function in Addiction Models

To investigate microglial contributions to relapse vulnerability, researchers employ specialized methodologies:

Microglial Depletion and Monitoring Protocol:

- CSF1R Inhibition: Administer PLX5622 (1200 ppm in diet) for 7-21 days to deplete ~80-90% of brain microglia

- Depletion Verification: Confirm microglial reduction via Iba1 immunohistochemistry or TMEM119 staining

- Behavioral Testing: Assess drug-seeking in self-administration or conditioned place preference paradigms

- Synaptic Analysis: Examine dendritic spine density and morphology using Golgi-Cox staining or two-photon imaging

- Cytokine Profiling: Measure TNFα, IL-1β, and IL-6 levels via ELISA or multiplex immunoassays

This approach enables researchers to establish causal relationships between microglial presence/function and drug-seeking behaviors [30] [32].

Astrocyte-Microglia Interaction Studies

To examine bidirectional communication between astrocytes and microglia in addiction models:

Conditioned Media Transfer Protocol:

- Primary Cell Cultures: Establish separate microglial and astrocytic cultures from rodent brains

- Drug Exposure: Treat microglia with drug of interest (e.g., 10μM cocaine) for 24 hours

- Conditioned Media Collection: Harvest media from drug-exposed microglia

- Astrocyte Exposure: Apply microglia-conditioned media to astrocyte cultures

- Functional Assessment: Measure (a) astrocytic glutamate transporter expression (Western blot), (b) inflammatory mediator release (multiplex cytokine array), and (c) morphological changes (GFAP immunostaining)

This methodology reveals how microglial activation directly influences astrocytic function, potentially contributing to glutamate dysregulation in addiction [30] [29].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Research Reagents for Investigating Neuroimmune Mechanisms in Addiction

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Research Application | Mechanistic Insight |

|---|---|---|---|

| Microglial Inhibitors | Minocycline, PLX3397, PLX5622 | Deplete or inhibit microglial function | Determine microglial necessity in drug-seeking behaviors |

| Cytokine Modulators | Etanercept (TNFα inhibitor), IL-1RA (IL-1 receptor antagonist) | Neutralize specific cytokine signaling | Identify cytokine-specific contributions to relapse vulnerability |

| TLR4 Pathway Antagonists | (+)-Naltrexone, Ibudilast (AV411) | Block innate immune receptor activation | Test role of pattern recognition receptors in drug reward |

| Transgenic Mouse Models | CX3CR1-GFP, Iba1-GFP, GFAP-GFP reporters | Visualize and isolate specific glial populations | Enable cell-type-specific manipulation and monitoring |

| GFAP Astrocyte Markers | Anti-GFAP antibodies, ALDH1L1 reporters | Identify and quantify astrocyte reactivity | Correlate astrogliosis with behavioral measures |

| Iba1 Microglia Markers | Anti-Iba1 antibodies, TMEM119 antibodies | Distinguish microglia from peripheral macrophages | Determine microglial activation state and morphology |

This toolkit enables researchers to systematically dissect the contributions of specific neuroimmune components to addiction pathophysiology [30] [29] [33].

Future Directions and Therapeutic Implications

The accumulating evidence for neuroimmune mechanisms in addiction relapse vulnerability suggests several promising research directions and clinical applications:

- Cell-Type-Specific Transcriptomics: Single-cell RNA sequencing of microglia and astrocytes from addiction models will reveal drug-induced molecular changes in specific glial subpopulations across brain regions and addiction stages.

- Temporal Dynamics: Investigating how neuroimmune responses evolve throughout the addiction cycle—from initial drug exposure to protracted abstinence—will identify critical windows for therapeutic intervention.

- Sex-Specific Mechanisms: Preliminary evidence suggests ovarian hormones influence neuroimmune signaling, necessitating dedicated studies of sex differences in glial contributions to addiction.

- Translational Biomarkers: Developing PET ligands for glial activation (e.g., TSPO radiotracers) could provide non-invasive biomarkers to monitor neuroimmune activation in patients and guide targeted therapies.

- Combination Therapies: Integrating neuroimmune-targeting agents with existing behavioral and pharmacological interventions may produce synergistic effects in reducing relapse risk.

The recognition that addiction produces lasting changes in brain immune function represents a fundamental shift in understanding this disorder. By expanding research beyond neuronal-centric models to include the active contributions of microglia and neuroimmune signaling, the field opens new avenues for developing mechanistically innovative treatments for substance use disorders.

Drug addiction is a chronic, relapsing disorder characterized by a profound loss of control over drug use, high rates of relapse, and a shift from voluntary, recreational drug use to compulsive drug-seeking and-taking habits [34] [3]. This transition represents a fundamental reorganization of behavioral control processes within the brain's striatal circuits. Research over the past two decades has established that this progression corresponds to a hierarchical shift in the neural control of behavior from the ventral striatum (involved in reward processing and goal-directed actions) to the dorsal striatum (critical for habit formation and automatic behaviors) [34] [35] [36]. This ventral-to-dorsal progression provides a neurobiological framework for understanding why addiction persists despite adverse consequences and why relapse remains a major challenge even after prolonged abstinence. The shift involves enduring neuroadaptations in cortico-basal ganglia-thalamic circuits that underlie the core features of addiction: compulsion to seek drugs, loss of control in limiting intake, and emergence of a negative emotional state during withdrawal [2]. This whitepaper examines the molecular, cellular, and circuit-level mechanisms underlying this transition and its implications for relapse vulnerability and therapeutic development.

Neuroanatomical Framework of Striatal Circuits

Functional Organization of the Striatum

The striatum serves as the primary input structure of the basal ganglia and is functionally heterogeneous. It can be broadly divided into ventral and dorsal subregions, each with distinct roles in motivation, learning, and behavior:

Ventral Striatum: Centered on the nucleus accumbens (NAc), this region integrates information from limbic structures and is crucial for processing reward, incentive salience ("wanting"), and the initial reinforcing effects of drugs of abuse [37] [38]. The NAc is further subdivided into core and shell subregions, with the shell responding to primary unconditioned stimuli and the core involved in conditioned responses [38].

Dorsal Striatum: Comprising dorsomedial (DMS) and dorsolateral (DLS) subregions, this area is essential for instrumental learning and habit formation [37] [36]. The DMS supports goal-directed actions sensitive to outcome value, while the DLS mediates stimulus-response habits that become automatic and resistant to devaluation [36].

These striatal regions are not independent but are interconnected through a spiral loop system via midbrain dopamine neurons, allowing information to flow from ventromedial to dorsolateral striatum [37] [36].

Microcircuitry of Medium Spiny Neurons

Approximately 95% of striatal neurons are GABAergic medium spiny neurons (MSNs) that form two major output pathways [37]:

Direct pathway MSNs (dMSNs): Express dopamine D1 receptors, project directly to output nuclei (substantia nigra pars reticulata and globus pallidus interna), and facilitate behavior initiation ("go" signal) [37].

Indirect pathway MSNs (iMSNs): Express dopamine D2 receptors, project indirectly to output nuclei via the globus pallidus externa and subthalamic nucleus, and suppress behavior ("brake" signal) [37].

These pathways are dynamically modulated by dopaminergic inputs from the ventral tegmental area (VTA) and substantia nigra pars compacta (SNc), and glutamatergic inputs from prefrontal cortex, hippocampus, amygdala, and thalamus [37].

Table 1: Key Striatal Subregions and Their Functional Roles in Addiction

| Striatal Subregion | Primary Function in Addiction | Key Input Regions | Behavioral Correlate |

|---|---|---|---|

| NAc Shell | Processing unconditioned drug effects; initial reward | Amygdala, Hippocampus, VTA | Drug "liking"; initial reinforcement |

| NAc Core | Processing conditioned cues; incentive salience | Prefrontal Cortex, Amygdala | Cue-induced craving; drug "wanting" |

| Dorsomedial Striatum | Goal-directed drug seeking; action-outcome learning | Prefrontal Cortex, Amygdala | Flexible, value-sensitive drug seeking |

| Dorsolateral Striatum | Habitual drug seeking; stimulus-response learning | Sensorimotor Cortex, Thalamus | Compulsive, inflexible drug seeking |

The Three-Stage Addiction Cycle and Striatal Transitions

Addiction progresses through a recurring three-stage cycle, each involving distinct neuroadaptations in striatal circuits [3] [2] [4]:

Binge/Intoxication Stage

During this initial stage, drugs of abuse powerfully increase dopamine transmission in the ventral striatum, particularly the NAc shell, producing intense euphoria and reinforcing drug use [3] [38]. All addictive substances converge on the mesolimbic dopamine system, albeit through different mechanisms:

- Psychostimulants (cocaine, amphetamine) directly increase synaptic dopamine by targeting dopamine transporters [38]

- Opioids and cannabinoids disinhibit dopamine neurons by reducing GABAergic inhibition of VTA neurons [36]

- Nicotine directly stimulates dopaminergic neurons via nicotinic acetylcholine receptors [4]

This stage primarily involves ventral striatal circuits and establishes strong Pavlovian associations between drug effects and environmental cues [38].

Withdrawal/Negative Affect Stage

With repeated drug use, counter-adaptations occur in the extended amygdala and its connections with striatal circuits, leading to a hypodopaminergic state and increased stress system activation during withdrawal [3] [2]. Key neuroadaptations include:

- Reduced dopamine D2 receptor availability in ventral striatum [3]

- Increased corticotropin-releasing factor (CRF) and dynorphin signaling in extended amygdala [2]

- Altered glutamate homeostasis affecting striatal synaptic plasticity [37]