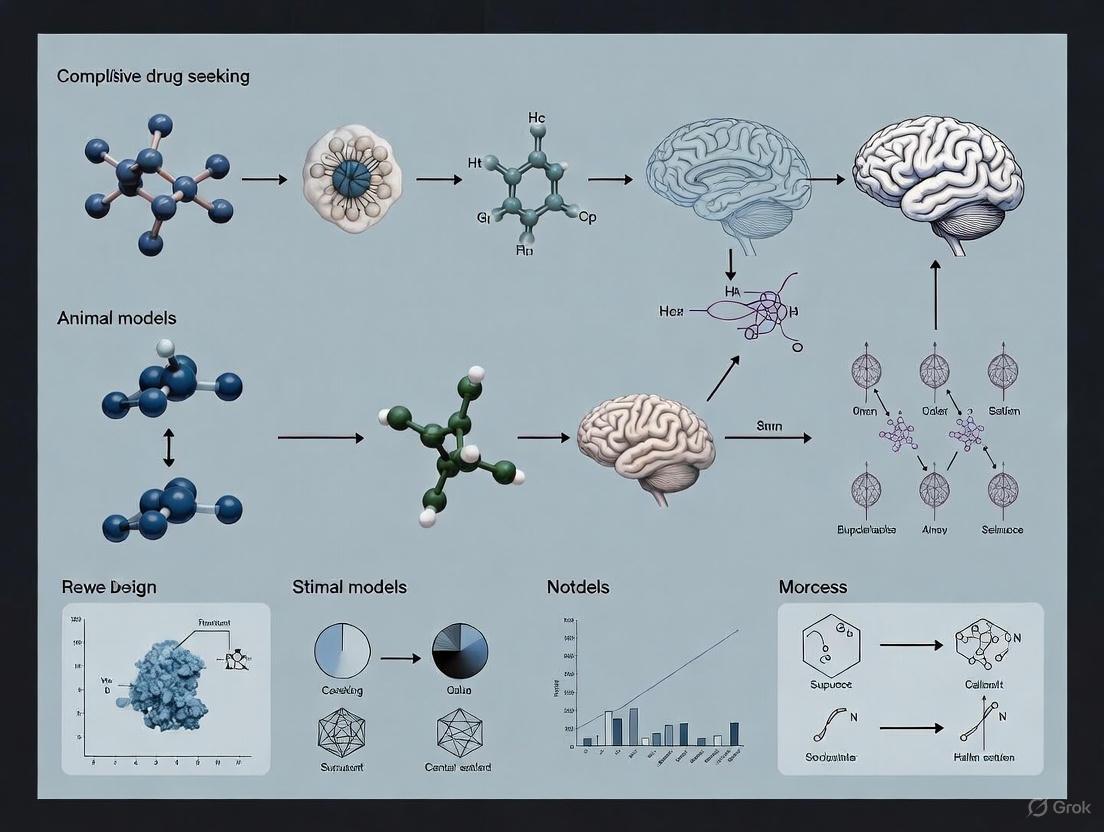

Modeling Compulsive Drug Seeking: Advanced Animal Models for Addiction Research and Therapeutic Development

This comprehensive review explores the evolution, application, and validation of animal models for studying compulsive drug-seeking behavior—a core feature of substance use disorders.

Modeling Compulsive Drug Seeking: Advanced Animal Models for Addiction Research and Therapeutic Development

Abstract

This comprehensive review explores the evolution, application, and validation of animal models for studying compulsive drug-seeking behavior—a core feature of substance use disorders. We examine foundational theories and neurocircuitry, detail established and emerging methodological approaches including self-administration paradigms with adverse consequences, and critically address conceptual challenges and optimization strategies. By integrating multidimensional validation frameworks and discussing translational gaps, this article provides researchers and drug development professionals with a sophisticated understanding of how preclinical models are advancing to better capture the complexity of human addiction, thereby enhancing the discovery of novel therapeutic interventions.

The Theoretical Basis of Compulsivity: From Brain Circuits to Behavioral Constructs

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: How does the DSM-5 define a Substance Use Disorder, and what is the role of "compulsivity"? The DSM-5 defines a Substance Use Disorder (SUD) as a problematic pattern of use leading to clinically significant impairment, as manifested by at least 2 out of 11 criteria within a 12-month period [1]. The criteria cover four main areas: impaired control, social impairment, risky use, and pharmacological criteria (tolerance and withdrawal) [2] [1].

While the term "compulsive" is commonly used in definitions of addiction (e.g., by NIDA), it is not explicitly listed as a standalone criterion in the DSM-5 [3]. Instead, the concept is operationally captured by criteria such as:

- "There is a persistent desire or unsuccessful efforts to cut down or control substance use."

- "The substance is often taken in larger amounts or over a longer period than was intended."

- "Important social, occupational, or recreational activities are given up or reduced because of substance use."

- "Continued substance use despite knowledge of having a persistent or recurrent physical or psychological problem that is likely to have been caused or exacerbated by the substance." [1]

Q2: What are the key differences between DSM-IV and DSM-5 criteria for Substance Use Disorders? The DSM-5 introduced major revisions to overcome limitations identified in the DSM-IV. The key changes are summarized below [2] [1]:

Table: Key Differences Between DSM-IV and DSM-5 Substance Use Disorder Criteria

| Feature | DSM-IV | DSM-5 |

|---|---|---|

| Diagnostic Categories | Two distinct disorders: Abuse and Dependence | A single, unified Substance Use Disorder |

| Diagnostic Threshold | Abuse: 1+ of 4 criteria. Dependence: 3+ of 7 criteria. | Mild: 2-3 criteria, Moderate: 4-5 criteria, Severe: 6+ criteria |

| Specific Criteria | Included "recurrent substance-related legal problems" | Removed "legal problems" and added "craving, or a strong desire or urge to use the substance" |

| Remission Specifiers | Early remission: 1-12 months without criteria (except tolerance/withdrawal) | Early remission: 3-12 months without criteria (craving may be present). Sustained remission: 12+ months without criteria (craving may be present). |

Q3: How is compulsive drug seeking operationalized in preclinical animal models? In preclinical research, "compulsivity" is primarily inferred from behaviors that persist despite adverse consequences, as animals cannot self-report feelings of compulsion. The main operationalizations are [4] [3]:

- Punishment-Based Models: Measuring the persistence of drug self-administration or seeking when the action is paired with an aversive outcome, such as a mild footshock or a bitter-tasting quinine adulterant [4] [3].

- Conflict-Based Models: Assessing the propensity to resume drug seeking after a period of abstinence enforced by the introduction of an adverse consequence (e.g., an electrified barrier near the drug lever) [4].

It is critical to note that these models are a subject of debate. A behavior observed under these conditions should be precisely described as "persistent responding despite adverse consequences," as multiple alternative explanations (e.g., reduced pain sensitivity, learning deficits) can account for the results without implying a human-like experience of "compulsion" [3].

Q4: What are common pitfalls when interpreting "compulsive-like" behavior in animals, and how can I avoid them? A primary pitfall is equating persistent drug use despite punishment directly with the clinical concept of compulsivity. Several factors must be controlled for to strengthen your conclusions [3]:

- Altered Sensitivity: Animals may be less sensitive to the punishing stimulus (e.g., footshock) at baseline or due to drug effects.

- Learned Resistance: Animals may acquire a learned resistance to the behavior-suppressing effects of punishment over time.

- Contingency Learning Deficits: The behavior may persist because the animal has not properly learned the association between its action and the punishment.

Troubleshooting Guide: How to control for alternative explanations in punishment models Table: Controls for Punishment-Based Models of Compulsive-like Behavior

| Problem Symptom | Possible Root Cause | Resolution Steps & Controls |

|---|---|---|

| High resistance to punishment in a subset of animals. | Innately reduced sensitivity to the aversive stimulus (e.g., footshock, quinine). | 1. Test baseline sensitivity: Conduct separate experiments to assess innate nociceptive thresholds or taste aversion in all animals before or after the main experiment.2. Use an alternative aversive stimulus: If an effect is found with one punisher (e.g., shock), confirm it with another type (e.g., quinine adulteration of an oral drug). |

| All animals show a gradual increase in punished responding over sessions. | Learned resistance to the punishing stimulus. | Include a control group: Test a separate group of animals that receive the same punishment contingency but for a non-drug reinforcer (e.g., sucrose). This determines if the resistance is specific to the drug reward. |

| An animal does not suppress responding even when punishment intensity is high. | Failure to learn the instrumental punishment contingency. | Verify contingency learning: Implement probe sessions where the punishment contingency is briefly omitted or signaled differently to test if the animal's behavior flexibly changes, indicating intact learning. |

| A treatment reduces punished drug-seeking. | The treatment generally reduces motivation or motor activity, rather than specifically affecting compulsion. | Test for specificity: Run a parallel experiment to confirm the treatment does not affect responding for a natural reward (e.g., food) under the same punishment schedule. |

Experimental Protocols for Modeling Compulsivity

Protocol 1: Punishment-Induced Suppression of Drug Seeking

Objective: To assess the persistence of drug-seeking behavior in the face of explicit adverse consequences [4] [3].

Methodology:

- Train Stable Self-Administration: Rats are trained to self-administer a drug (e.g., cocaine, alcohol) on a fixed-ratio schedule until stable baseline intake is established.

- Introduce Punishment Contingency: In subsequent sessions, a portion (e.g., 30-50%) of the drug-reinforced responses are concurrently paired with a mild, unpredictable footshock (e.g., 0.2-0.5 mA, 0.5 sec duration) through the grid floor.

- Measure and Classify: Animals are classified based on their response suppression. "Compulsive-like" or "Punishment-Resistant" animals are typically defined as those maintaining a high rate of drug intake (e.g., >80% of baseline) despite the punishment, compared to "Punishment-Sensitive" animals that significantly suppress their intake [4].

Protocol 2: Conflict-Based Relapse After Self-Abstinence

Objective: To model relapse to drug seeking after a period of voluntary abstinence driven by adverse consequences [4].

Methodology:

- Self-Administration Training: As in Protocol 1.

- Induce Self-Abstinence: Introduce an "electric barrier" or consistent punishment that makes the cost of drug-seeking prohibitively high. The animal is allowed to choose not to respond.

- Define Abstinence Criterion: Animals that cease lever-pressing for the drug for a set number of consecutive days (e.g., 3 days) are considered to have achieved self-abstinence.

- Probe for Relapse: In a subsequent session where the punishment is temporarily removed, the animal is exposed to drug-paired cues, a drug prime (small non-contingent infusion), or stress. The resumption of drug-seeking behavior is measured as "relapse." [4]

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

Table: Key Reagents for Preclinical Models of Compulsive Drug Seeking

| Item | Function & Application |

|---|---|

| Operant Conditioning Chamber | Sound-attenuated box with levers, cue lights, and a drug infusion system. The core apparatus for drug self-administration studies. |

| Programmable Footshock Generator | Delivers precise, scrambled mild electric shocks to the chamber grid floor to serve as the adverse consequence in punishment models. |

| Intravenous Catheter & Swivel System | Allows for chronic, intravenous drug self-administration in freely moving rodents. |

| Quinine Hydrochloride | A bitter tastant used to adulterate oral drug solutions (e.g., alcohol) to create an aversive consequence. |

| Microdialysis/Licrodialysis System | For in vivo sampling of neurotransmitters (e.g., glutamate, dopamine) from specific brain regions during compulsive-like behavior. |

| DREADDs (Designer Receptors Exclusively Activated by Designer Drugs) or Chemogenetics Kit | Tools for selectively activating or inhibiting specific neural circuits to establish causal links with behavior. |

| c-Fos or pERK Antibodies | Immunohistochemical markers for mapping neuronal activation in brain tissue following behavioral tests. |

| Schedule-Controlled Contingency Software | Software (e.g., Med-PC) to program complex reinforcement schedules and precisely control experimental sessions. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: What is the functional organization of the corticostriatal pathway in the context of goal-directed behaviors? The corticostriatal pathway is the primary input channel to the basal ganglia and is topographically organized. It integrates information across reward, cognitive, and motor functions to orchestrate goal-directed behaviors [5]. The striatum is divided into functional territories: the ventral striatum (reward), the caudate nucleus (cognition), and the putamen (motor control). These regions are part of a larger cortico-basal ganglia-thalamo-cortical loop, where the cortex projects to the striatum, which then projects through the pallidal complex and substantia nigra to the thalamus, and back to the cortex [5].

FAQ 2: How do dopamine and glutamate interact synaptically in the striatum to influence behavior? Dopamine and glutamate interact at the level of the striatal medium spiny neurons (MSNs) to modulate synaptic plasticity, including the induction of long-term depression (LTD) and long-term potentiation (LTP) [6]. This interaction is critical for reward-related learning and the fine-tuning of behavioral repertoire. Dopaminergic input from the substantia nigra pars compacta (SNc) and ventral tegmental area (VTA) terminals converges with glutamatergic inputs from the cortex and thalamus onto the spines and dendritic shafts of MSNs, allowing dopamine to regulate the strength of cortical signals [5] [6].

FAQ 3: What neurochemical imbalances are observed in the frontal cortex in compulsive disorders? In individuals with Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder (OCD), a disorder characterized by compulsive behavior, elevated glutamate levels and a disrupted balance between glutamate and GABA (gamma-aminobutyric acid) are observed in the anterior cingulate cortex (ACC). Specifically, studies using 7-Tesla magnetic resonance spectroscopy (MRS) show that OCD participants have significantly higher Glu:GABA ratios in the ACC compared to healthy volunteers. Furthermore, in the supplementary motor area (SMA), glutamate levels positively correlate with clinical measures of compulsive behavior [7].

FAQ 4: How do drugs of abuse alter the dopamine system to contribute to addiction? Drugs of abuse induce large and fast increases in extracellular dopamine in the striatum, particularly in the ventral striatum/nucleus accumbens, which is associated with their reinforcing effects (the "high") [8] [9]. In individuals with addiction, chronic drug use leads to decreases in dopamine D2 receptors and reduced dopamine release in the striatum. This hypodopaminergic state is linked to reduced activity in prefrontal regions (orbitofrontal cortex, cingulate gyrus, dorsolateral prefrontal cortex), underlying symptoms like loss of inhibitory control and compulsive drug intake [8].

Troubleshooting Guide: Common Experimental Challenges

Behavioral Modeling

Table: Addressing Challenges in Modeling Compulsive Drug Seeking

| Challenge | Potential Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| High behavioral variability in animal models | Individual differences in transition from controlled to compulsive use. | Use progressive ratio schedules or long-access self-administration protocols to model escalation. Select subjects based on behavioral cut-offs (e.g., high vs. low compulsive responders) [9] [10]. |

| Difficulty distinguishing goal-directed from habitual actions | Over-reliance on a single behavioral test; lack of specific molecular markers. | Implement outcome devaluation and contingency degradation protocols [10]. Use circuit-specific monitoring (e.g., fiber photometry in DMS vs DLS) to confirm a shift from mesostriatal to nigrostriatal dopamine dependency [10]. |

Neurochemical and Circuit Interrogation

Table: Addressing Challenges in Neurochemical and Circuit Analysis

| Challenge | Potential Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Measuring subtle neurotransmitter changes in vivo | Low sensitivity of techniques; confounding signals from metabolites. | Use high-field MRS (7-Tesla) with optimized sequences (e.g., semi-LASER) to reliably separate glutamate, glutamine, and GABA [7]. Control for neuronal integrity by co-measuring N-acetylaspartate (NAA) [7]. |

| Achieving pathway-specific manipulation | Off-target effects from traditional pharmacological or lesion approaches. | Employ cell-type-specific cre-lox systems and projection-targeted optogenetics/chemogenetics (DREADDs) to selectively manipulate dSPNs vs iSPNs, or VTA vs SNc dopamine neurons [11] [10]. |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Measuring Drug-Induced Dopamine Release Using PET Imaging

This protocol is used to investigate the role of fast dopamine increases in the reinforcing effects of drugs of abuse in human participants [8].

- Radiotracer Administration: Inject a specific D2 dopamine receptor radioligand (e.g., [¹¹C]raclopride or [¹⁸F]N-methylspiroperidol) intravenously.

- PET Data Acquisition: Use Positron Emission Tomography (PET) to monitor the binding of the radioligand in the striatum over time. Baseline binding potential is an index of D2 receptor availability.

- Drug Challenge: Administer the drug of interest (e.g., intravenous methylphenidate or amphetamine) during the scan.

- Data Analysis: Calculate the displacement of the radioligand by the drug-induced increase in endogenous dopamine. A greater displacement indicates a larger dopamine release.

- Behavioral Correlation: Correlate the magnitude of dopamine release (percent change in binding potential) with subjective self-reports of "high" or "euphoria" using standardized rating scales.

Protocol 2: Assessing Glutamate and GABA in Cortical Regions Using 7-Tesla MRS

This protocol details the use of high-field MRS to quantify regional levels of glutamate and GABA, providing an index of excitatory/inhibitory balance in disorders like OCD [7].

- Subject Preparation: Recruit participant groups (e.g., individuals with OCD and healthy controls). Acquire high-resolution anatomical scans (e.g., T1-weighted MRI).

- Voxel Placement: Precisely place spectroscopic voxels in regions of interest based on anatomical landmarks. Key regions include the Anterior Cingulate Cortex (ACC), Supplementary Motor Area (SMA), and a control region like the Occipital Cortex (OCC).

- Spectral Acquisition: Use a semi-LASER sequence or equivalent optimized for 7-Tesla to acquire spectra. This ensures reliable and separate quantification of Glu and GABA.

- Spectral Processing and Quantification: Process the raw data to remove artifacts and fit the spectra using specialized software (e.g., LCModel) to estimate absolute concentrations of Glu, GABA, and other metabolites (e.g., Gln, NAA).

- Statistical Analysis: Compare metabolite levels between groups within each voxel. Perform correlation analyses between metabolite levels (e.g., Glu in SMA) and behavioral scores (e.g., Yale-Brown Obsessive Compulsive Scale (YBOCS) or Obsessive-Compulsive Inventory (OCI)).

Signaling Pathways and Circuit Diagrams

Direct and Indirect Pathway Circuit Logic

Addiction Cycle Neurocircuitry

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

| Item | Function/Application |

|---|---|

| [¹¹C]raclopride | A radioligand for Positron Emission Tomography (PET) imaging used to quantify dopamine D2/D3 receptor availability and measure drug-induced changes in synaptic dopamine levels in the striatum [8]. |

| DREADDs (Designer Receptors Exclusively Activated by Designer Drugs) | Chemogenetic tools (e.g., hM3Dq, hM4Di) used for remote, reversible, and cell-type-specific manipulation of neuronal activity in defined circuits (e.g., selective targeting of D1 vs D2 MSNs) [10]. |

| Sapap3 Knockout Mice | A genetic mouse model lacking the SAPAP3 protein, which is a postsynaptic scaffolding protein at corticostriatal synapses. These mice exhibit excessive self-grooming and anxiety-like behaviors, providing a model for compulsive behaviors relevant to OCD [12]. |

| 7-Tesla MRI/MRS Scanner | High-field magnetic resonance imaging and spectroscopy hardware that allows for the reliable and separate quantification of neurometabolites, particularly glutamate and GABA, in specific brain regions like the ACC and SMA [7]. |

| AAV-hSyn-FLEX-ChR2 | A Cre-dependent adeno-associated virus (AAV) carrying Channelrhodopsin-2 (ChR2) under a human synapsin promoter. Used for projection-specific optogenetic stimulation of defined neural pathways (e.g., corticostriatal projections) [10]. |

Frameworks in Focus: FAQ

Q1: What is the core distinction between the "wanting" and "liking" processes in the Incentive-Sensitization Theory?

The Incentive-Sensitization Theory posits that "liking" (the pleasure derived from a reward) and "wanting" (the motivation to obtain it) are distinct processes [13] [14]. Repeated drug use can sensitize the mesocorticolimbic dopamine system, particularly the neural pathways that attribute incentive salience to rewards and their cues [15] [13]. This leads to a core pathology: a dramatic increase in pathological "wanting" for the drug, while "liking" for the drug may remain unchanged or even decrease [13] [14]. This sensitized "wanting" is persistent and can trigger compulsive seeking and relapse, often in response of drug-associated cues, long after withdrawal has ended [13].

Q2: How does the habit formation theory explain the transition from voluntary drug use to compulsive behavior?

The habit theory suggests a shift from action-outcome to stimulus-response control [16] [17]. Early drug use is goal-directed, driven by the desirable outcome (e.g., euphoria). With repetition, the behavior becomes habitual [16]. In this stage, drug-seeking is automatically triggered by contextual cues (e.g., a specific location) with minimal influence from the current value of the outcome, making the behavior inflexible and persistent even when the outcome is devalued (e.g., when the negative consequences outweigh the high) [16] [17]. Some research further proposes distinguishing between motor habits (simple S-R contingencies) and motivational habits (S-R connections modulated by an urge, such as craving) [16].

Q3: What is the role of impaired executive control in addiction?

Executive control, governed primarily by the prefrontal cortex, encompasses higher-order cognitive functions like inhibitory control, working memory, and cognitive flexibility [18]. Impaired executive control, particularly deficient response inhibition, is theorized to contribute to addiction by reducing the ability to suppress strong urges to take drugs, despite negative consequences [18] [19]. This deficit can create a vicious cycle where impaired inhibitory control allows for uninhibited obsessions and compulsions, which in turn further reinforces the behavior [18]. This dysfunction may represent a pre-existing vulnerability factor for developing addiction [18].

Q4: Can these frameworks be applied to behavioral addictions like Gambling Disorder?

Yes. The Incentive-Sensitization Theory is considered a promising model for understanding Gambling Disorder [15] [14]. The uncertainty of reward in gambling is thought to enhance dopaminergic activity in the mesolimbic pathway, potentially sensitizing the "wanting" system and increasing the incentive value of gambling-related cues [15]. This suggests transdiagnostic neurobiological mechanisms underlying both substance and behavioral addictions [15] [14].

Q5: How do stress and anxiety interact with these frameworks in addiction?

Significant evidence points to a phenomenon known as cross-sensitization [15]. This means that sensitization to one stimulus (e.g., a drug) can enhance the sensitivity and dopaminergic response to another (e.g., stress) [15]. Since stress is a major trigger for relapse, this interaction creates a powerful mechanism through which sensitized neural 'wanting' pathways, anxiety, and substance use can coalesce and exacerbate comorbid pathology [15].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Experimental Protocols & Reagents

Key Behavioral Paradigms for Modeling Addiction in Animals

The table below summarizes core behavioral assays used to investigate different aspects of addiction pathology [20].

Table 1: Key Animal Models in Addiction Research

| Behavioral Paradigm | Core Construct Measured | Methodology Summary | Key Interpretive Consideration |

|---|---|---|---|

| Behavioral Sensitization [20] [13] | Incentive Sensitization / Neural Hypersensitivity | Repeated, experimenter-administered non-contingent drug exposure (e.g., daily i.p. injections), followed by a drug challenge after a withdrawal period. Locomotor activity is measured. | Sensitization (enhanced locomotor response) is indirect evidence of drug-induced neuroadaptations in motivation circuitry. Sensitization can be context-specific [13]. |

| Drug Self-Administration (SA) [20] | Drug-Taking & Motivation | An animal performs an operant response (e.g., lever press, nose poke) to receive an intravenous drug infusion. | Allows for contingent drug delivery. Key variations include progressive ratio (to measure motivation) and SA with punishment (to measure compulsivity). |

| Reinstatement Model [20] | Relapse | After SA and subsequent extinction of drug-seeking, the behavior is reinstated by a drug prime, a stressor, or presentation of drug-paired cues. | Models triggers of relapse in humans (drug exposure, stress, cues). Considered the gold standard for studying relapse. |

| Conditioned Place Preference (CPP) [20] | Reward Learning / Pavlovian Conditioning | An animal learns to associate one distinct chamber with a drug and another with saline. Preference for the drug-paired chamber is tested in a drug-free state. | Measures the conditioned rewarding effects of drugs and cues. It involves non-contingent drug administration. |

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Their Functions

| Reagent / Tool Category | Example(s) | Primary Function in Research |

|---|---|---|

| Dopamine Receptor Agonists/Antagonists | SCH-23390 (D1 antagonist), Raclopride (D2 antagonist) | To pharmacologically dissect the role of specific dopamine receptor subtypes in sensitization, SA, and reinstatement [20] [13]. |

| c-Fos Immunohistochemistry | c-Fos antibodies | To map and quantify neural activity in specific brain regions (e.g., NAc, VTA, PFC) following behavioral tests like a sensitization challenge or cue-induced reinstatement [21]. |

| Viral Vector Technology | DREADDs (Designer Receptors Exclusively Activated by Designer Drugs) | For cell-type-specific neuromodulation (inhibition or excitation) to establish causal roles of specific neural circuits in addiction behaviors with temporal precision. |

| Radioligands for PET Imaging | [11C]Raclopride | Used in tandem with microdialysis or Positron Emission Tomography (PET) in animals and humans to measure drug-induced dopamine release, providing evidence for sensitization [14]. |

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Challenges

Challenge 1: Failure to observe behavioral sensitization.

- Potential Cause: The expression of sensitization is often context-dependent. If the drug challenge is given in an environment that is different from the environment where the drug was experienced during the induction phase, sensitization may not be expressed [13].

- Solution: Ensure consistency between the training and testing environments (same context, handling procedures, etc.). Control for the potential role of context by including separate groups of animals tested in paired vs. unpaired environments.

Challenge 2: High variability in self-administration acquisition.

- Potential Cause: Individual genetic and behavioral traits significantly influence vulnerability to drug use. Using outbred rodent strains without pre-screening can lead to high variability, masking strong effects in a subset of animals [20].

- Solution: Implement pre-screening to isolate subpopulations with specific traits. Common models include:

- High-Responder (HR) vs. Low-Responder (LR): Based on initial locomotor response to a novel environment, predicting acquisition of drug SA [20].

- Sign-Tracker (ST) vs. Goal-Tracker (GT): Based on individual variation in Pavlovian conditioned approach, with STs showing greater cue-triggered "wanting" and being more vulnerable to relapse [20].

Challenge 3: Distinguishing goal-directed from habitual actions in animals.

- Potential Cause: The standard outcome devaluation test (e.g., using LiCl to induce taste aversion) can be confounded by general motivational or sensorimotor effects [17].

- Solution: Use a two-action, outcome devaluation task. Train animals to perform two different actions (e.g., press left lever, press right lever) for two distinct outcomes. Then, devalue one outcome (e.g., specific food) by specific satiety or LiCl pairing. In a subsequent extinction test, a goal-directed animal will reduce performance of the action associated with the devalued outcome, while a habitual animal will not [17].

Conceptual Workflow and Signaling Pathways

Incentive Sensitization in the Mesolimbic Pathway

Experimental Workflow for Modeling Compulsive Seeking

FAQs and Troubleshooting Guides

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: What are the core factors that determine individual vulnerability in animal models? Individual vulnerability to compulsive drug seeking is not determined by a single factor but by the interaction of three core domains:

- Genetic & Biological Factors: The genetic makeup of an animal accounts for a significant portion of its risk. This includes innate predispositions in brain reward circuitry and epigenetic modifications that can be inherited transgenerationally [22].

- Environmental Factors: The animal's living conditions, such as an Enriched Environment (EE) that provides sensory, cognitive, and social stimulation, can serve as a protective factor, reducing drug consumption and relapse [23]. Conversely, stressful environments increase vulnerability.

- Behavioral Traits: Innate behavioral characteristics, such as high impulsivity, sensation-seeking, or a sign-tracking (vs. goal-tracking) phenotype, are strong predictors of increased drug self-administration and relapse [20].

FAQ 2: How can I reliably segregate populations into "addiction-like" and "resilient" groups in my experiments? The most valid method is to use a multi-criteria approach based on key symptoms of addiction, rather than relying on a single measure like total drug intake. A standard protocol involves [22] [20]:

- Drug Self-Administration: Allow animals to self-administer a drug.

- Progressive Ratio (PR) Testing: Assess the motivation to seek the drug by measuring the "break point" (the maximum number of lever presses an animal will perform for a single drug infusion).

- Persistence of Use despite Negative Consequences: Challenge drug-taking by pairing it with an aversive stimulus (e.g., a mild footshock). Animals are then classified based on their combined scores across these measures, typically identifying the top 20-25% as the "addiction-like" group [22].

FAQ 3: My animal model shows high drug intake but does not persist when challenged. Is this still a valid model of addiction? High drug intake alone is not synonymous with the clinical diagnosis of addiction, which is characterized by a loss of control. The DSM-5 criteria for Substance Use Disorder include compulsive use despite harmful consequences [24]. An animal that ceases use when faced with a negative consequence (like footshock) is demonstrating intact control and is often classified as a "Non-addict" or "Resilient" phenotype in research settings [22] [20]. Your model is valid for studying drug use, but to model the core pathology of addiction, incorporating a measure of persistence despite punishment is crucial.

FAQ 4: Can the vulnerability acquired by a parent generation be passed to offspring? Yes, research demonstrates transgenerational transmission of addiction vulnerability. Crucially, this transmission is linked to the motivational state of the parent, not merely drug exposure. Offspring (F1 and F2 generations) of male rats classified as "Addict" based on high incentive motivation for cocaine themselves show higher motivation to seek cocaine. This effect is not seen in the offspring of rats that passively received the same amount of cocaine (yoked controls), highlighting the role of experience-driven epigenetic mechanisms [22].

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Issues

Issue 1: Low differentiation between "Addiction-like" and "Non-addict" phenotypes.

- Potential Cause: Inadequate stringency in the classification criteria.

- Solution:

- Ensure you are using a multi-symptomatic approach (e.g., combining motivation (PR) and persistence despite punishment).

- Consider adjusting the aversive stimulus in the punishment test to a level that is sufficient to deter most "Non-addict" animals but is overcome by the "Addiction-like" group.

- Verify that your statistical method for classification (e.g., selecting the top and bottom percentiles of a combined z-score) is correctly implemented.

Issue 2: High variability in self-administration data within treatment groups.

- Potential Cause: Unaccounted for innate behavioral traits influencing the behavior.

- Solution:

- Pre-screen animals: Before beginning drug studies, screen for known predictive traits like impulsivity (using the 5-choice serial reaction time task) or sign-tracking vs. goal-tracking behavior. You can then balance these traits across experimental groups or use them as co-variates in your analysis [20].

- Control environmental factors: Standardize housing conditions (e.g., all isolated or all enriched) to minimize this source of variability. Note that standard laboratory housing is a form of environmental impoverishment that can heighten vulnerability [23].

Issue 3: Difficulty in translating "Environmental Enrichment" (EE) from rodent to human studies.

- Potential Cause: EE is a multi-faceted construct that is complex to define and measure in humans.

- Solution: A recently developed self-report EE scale for humans can be a valuable translational tool. This scale measures components such as [23]:

- Physical activity and exercise.

- Social interaction and support.

- Cognitive stimulation (e.g., reading, playing music).

- Sensory richness and novelty. Validated in smokers and patients with alcohol use disorder, this scale confirms that higher EE scores are associated with lower consumption, dependence, and craving [23].

Data Presentation

Quantitative Data on Individual Vulnerability Factors

Table 1: Key Factors Predicting Individual Vulnerability in Animal Models

| Factor Domain | Specific Factor / Paradigm | Key Quantitative Finding | Associated Behavioral Phenotype |

|---|---|---|---|

| Genetic/Epigenetic | Transgenerational Inheritance (Motivation-driven) [22] | F1 & F2 offspring of "Addict" F0 rats showed ~30-50% higher lever presses (FR5) and break points (PR) for cocaine. | Increased motivation and vulnerability to cocaine-seeking. |

| Environmental | Environmental Enrichment (EE) in Smokers [23] | Higher EE scores were significantly correlated with lower nicotine consumption, dependence, and craving. | Protective effect, reduced consumption and relapse risk. |

| Behavioral Trait | Sign-Tracking (ST) vs. Goal-Tracking (GT) [20] | ST animals show significantly higher rates of drug-seeking and relapse after extinction compared to GT animals. | Increased propensity for cue-induced craving and relapse. |

| Behavioral Trait | Impulsivity (5-CSRTT) [20] | High impulsivity scores predict faster acquisition of drug self-administration and increased drug intake. | Predisposition to initiate and maintain drug use. |

| Behavioral Trait | High Responder (HR) vs. Low Responder (LR) [20] | HR animals (high novelty-induced locomotion) acquire amphetamine self-administration at a lower dose than LR animals. | Increased vulnerability to the initial acquisition of drug use. |

Experimental Protocols for Key Methodologies

Protocol 1: Classifying "Addiction-like" vs. "Non-addict" Phenotypes using a Multi-Criteria Approach [22]

- Subjects: Male Sprague-Dawley rats.

- Drug Self-Administration (SA) Training:

- Implant intravenous catheters.

- Place animals in operant chambers equipped with two levers (active and inactive).

- Train animals on a Fixed-Ratio 1 (FR1) schedule, where each press on the active lever delivers a cocaine infusion (e.g., 0.75 mg/kg/infusion). Gradually increase the schedule to FR5.

- Conduct daily 4-hour sessions for approximately 10-12 days.

- Progressive Ratio (PR) Testing:

- To assess motivation, switch the reinforcement schedule to a PR, where the response requirement for each subsequent infusion increases exponentially.

- The session ends when the animal fails to meet the response requirement within a set time (e.g., 1 hour).

- The primary outcome is the break point (the last ratio completed).

- Persistence despite Punishment:

- During SA sessions, introduce a contingent punisher (e.g., a mild footshock) upon active lever presses.

- The intensity is set to deter most animals but is overcome by the most compulsive ones.

- Measure the percentage of suppression of drug intake compared to baseline.

- Classification:

- For each animal, calculate normalized Z-scores for (a) drug intake under FR5, (b) break point under PR, and (c) resistance to punishment.

- Sum the Z-scores to create a combined "addiction score."

- Classify the top 25% of the population as "Addiction-like" and the bottom 40% as "Non-addict" for further study.

Protocol 2: Assessing the Protective Role of Environmental Enrichment (EE) [23]

- EE Construction for Rodents:

- Control Group: Standard laboratory housing (2-3 animals per standard cage).

- EE Group: Larger cages (e.g., 100 x 50 x 50 cm) housing 8-12 animals.

- Enrichment Items: Provide a variety of stimulating objects such as running wheels, plastic tubes, wooden blocks, nesting materials, and Lego structures. Re-arrange and replace a portion of the objects 2-3 times per week to maintain novelty.

- Experimental Timeline:

- Pre-Exposure: House animals in their respective (EE or control) conditions for 2-4 weeks prior to any drug exposure.

- Drug SA or Relapse: Proceed with standard drug self-administration protocols. To test the therapeutic effect of EE, it can also be introduced during abstinence after SA training.

- Key Outcome Measures:

- Compare the two groups on measures of:

- Acquisition: Rate and level of drug SA.

- Motivation: Break point on a PR schedule.

- Relapse: Drug-seeking behavior after extinction, triggered by cues, stress, or a prime dose of the drug.

- Compare the two groups on measures of:

Signaling Pathways and Experimental Workflows

Vulnerability Factor Integration

Multi-Criteria Phenotype Classification

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Materials and Reagents for Modeling Individual Vulnerability

| Item / Reagent | Function / Application | Specific Examples / Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Intravenous Catheters | Chronic, reliable delivery of drugs during self-administration sessions. | Typically made of Silastic tubing; surgically implanted into the jugular vein. Requires regular flushing with heparinized saline to maintain patency. |

| Operant Conditioning Chambers | The controlled environment for measuring drug-seeking and taking behaviors. | Equipped with levers, cue lights, speakers (for tones), and an infusion pump. Often housed within sound-attenuating cubicles. |

| Controlled Substances | The primary reinforcer in the study. | Cocaine HCl, heroin, methamphetamine, etc. Doses are typically reported in mg/kg/infusion. Must be handled and stored according to strict DEA and institutional schedules [25]. |

| Footshock Generator | To provide a quantifiable negative consequence for assessing compulsive use. | Used in "persistence despite punishment" tests. Intensity is critical (e.g., 0.1-0.5 mA); must be calibrated to deter most but not all animals. |

| Environmental Enrichment Caging | To model the protective effects of a stimulating environment. | Large cages containing running wheels, plastic toys, wooden blocks, and shelters. Objects are rotated regularly to maintain novelty [23]. |

| Epigenetic Analysis Kits | To investigate transgenerational and experience-driven mechanisms. | Kits for Bisulfite Sequencing (to analyze DNA methylation) and ChIP (Chromatin Immunoprecipitation) are used on tissue samples (e.g., sperm, brain regions like NAc) [22]. |

Operationalizing Compulsion: Key Behavioral Paradigms and Protocols

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: Why is drug self-administration considered the "gold standard" in preclinical addiction research?

Drug self-administration is regarded as the gold standard because it has high predictive validity and face validity for modeling human substance use disorders [26] [27]. It is an operant conditioning paradigm where animals voluntarily perform a behavior (e.g., lever press) to receive a drug infusion, directly measuring the drug's reinforcing properties [28] [20]. Virtually all drugs abused by humans are self-administered by animals, and the patterns of drug intake resemble those observed in humans [28] [27]. This model is critical for assessing the abuse liability of novel compounds and the efficacy of potential pharmacotherapies [28] [29].

Q2: What are the key differences between Short Access (ShA) and Long Access (LgA) protocols, and why are they important?

The key difference lies in session duration and the resulting drug intake pattern, which models different stages of addiction.

- Short Access (ShA): Typically involves limited daily sessions (e.g., 1-2 hours). This protocol produces stable, controlled drug intake and is often used to study the initial acquisition and maintenance of drug-taking behavior [28].

- Long Access (LgA): Involves extended daily sessions (e.g., >4-6 hours). This protocol leads to an escalation of drug intake over time, modeling the transition from controlled use to the compulsive, addiction-like drug seeking seen in humans [28] [20]. Escalation is a hallmark of addiction and reflects a loss of control over intake [28].

Q3: What common technical challenge is associated with intravenous catheters in rodent studies, and how can it be managed?

The primary challenge is maintaining catheter patency (preventing blockages and failures) over the course of a long-term study [30]. This can be managed through:

- Aseptic Surgical Technique: Ensuring sterile implantation of the jugular or femoral vein catheter.

- Post-operative Care: Allowing sufficient recovery time (e.g., 5-7 days) before starting experiments [30].

- Catheter Maintenance: Implementing a strict daily flushing regimen with heparinized saline and an antibiotic solution to prevent clotting and infection [30].

- Patency Testing: Regularly verifying catheter functionality, for example, by administering a short-acting anesthetic (e.g., propofol) through the catheter and observing for a rapid effect [30].

Q4: How can I troubleshoot a situation where my animals are not acquiring stable self-administration (e.g., poor lever discrimination)?

Poor acquisition can stem from several factors. The troubleshooting guide below outlines common issues and solutions.

| Problem | Potential Causes | Recommended Solutions |

|---|---|---|

| Failure to acquire self-administration | Incorrect drug dose, surgical complications, poor health | Validate catheter patency, adjust drug dose, ensure full post-surgical recovery [30] |

| Poor active/inactive lever discrimination | Inadequate training, weak reinforcement | Implement contingent advancement training protocols, use a distinct cue light for active lever, consider mild food restriction to enhance initial learning [30] |

| High variability in drug intake | Genetic heterogeneity, differences in catheter function | Use genetically defined rodent strains, standardize handling procedures, routinely check catheter patency [30] [31] |

Q5: What neurobiological adaptations are associated with the transition to compulsive drug seeking?

Chronic drug self-administration induces persistent neuroadaptations, particularly within the mesolimbic dopamine system and associated circuits [28]. Key adaptations include:

- Synaptic Plasticity: Long-term potentiation (LTP) and depression (LTD) in the Ventral Tegmental Area (VTA) and Nucleus Accumbens (NAc) [28].

- Molecular Changes: Increased expression of transcription factors like ΔFosB and CREB in the NAc, which regulate gene expression related to addiction [28].

- Glutamatergic System Dysregulation: Functional upregulation of AMPA receptors and decreased expression of the glutamate transporter GLT1 in the NAc, contributing to heightened relapse vulnerability [28].

- Circuit-Level Shifts: A progression from ventral striatal (reward-driven) to dorsal striatal (habit-driven) control over drug-seeking behavior [28].

Experimental Protocols & Methodologies

Core Self-Administration Paradigms

Intravenous Self-Administration (IVSA) Protocol This is the most direct method to model human drug taking [28] [27] [30].

- Animal Preparation: Surgically implant an indwelling intravenous catheter into the jugular or femoral vein of a rodent (rat or mouse). Allow 5-7 days for recovery [30].

- Acquisition Training: Place the animal in an operant chamber. A response on the "active" lever results in:

- Schedule of Reinforcement:

- Start with a Fixed-Ratio 1 (FR1) schedule, where each active lever press delivers one drug infusion.

- Gradually increase the response requirement (e.g., to FR2, FR4) to strengthen the operant behavior [30].

- Session Type:

- Short Access (ShA): Conduct 1-2 hour daily sessions to establish stable baseline intake.

- Long Access (LgA): Conduct 6+ hour daily sessions to induce escalation of drug intake [28].

Oral Self-Administration Protocol Primarily used for alcohol research, this model has high face validity for human drinking [26] [27].

- Two-Bottle Choice Paradigm: In the home cage, provide two bottles: one with an alcohol solution (e.g., 10-12% v/v) and one with water. Measure fluid consumption over 24 hours to assess preference [26] [27].

- Operant Oral Self-Administration: Animals perform a lever press or nose poke to gain access to a sipper tube containing an alcohol solution. This allows for the measurement of motivated responding for the drug [27].

- Intermittent-Access Model: To model binge-like drinking, offer the alcohol solution for 24 hours, followed by 24 hours of abstinence. This cycle leads to higher and more pharmacologically relevant levels of alcohol intake [27].

Advanced Behavioral Schedules

To probe different facets of addiction, more complex schedules are used after stable self-administration is acquired.

- Progressive Ratio (PR): The response requirement for each subsequent drug infusion increases exponentially (e.g., 1, 2, 4, 6, 9...). The final ratio completed before the animal ceases to respond is the "breakpoint," which quantifies the motivation to work for the drug [28] [32].

- Extinction & Reinstatement: Drug-seeking behavior is "extinguished" by withholding the drug and its associated cues. Subsequently, "reinstatement" of drug-seeking is triggered by a priming injection of the drug, exposure to drug-associated cues, or a stressor. This models relapse in humans [28] [20] [30].

- Choice Procedures: Animals are given a choice between a drug infusion and an alternative reinforcer (e.g., sweet food or a social interaction). This paradigm is highly predictive of human outcomes and measures the relative value of the drug [32] [20].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

The following table details key materials required for establishing a self-administration study.

| Item | Function & Application | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Intravenous Catheters | Chronic, direct delivery of drugs into the bloodstream [30]. | Material (e.g., silicone), size, and vessel (jugular vs. femoral) are critical for long-term patency [30]. |

| Operant Chambers | Controlled environment where animals learn the lever-press/nose-poke response for drug [28]. | Must include active/inactive manipulanda, cue lights, tone generator, and an infusion pump. |

| Infusion Pumps | Precisely deliver a set volume of drug solution contingent on a correct response [28]. | Must be calibrated for the specific drug dose (mg/kg/infusion) and animal species. |

| Drugs of Abuse | The primary reinforcer (e.g., Cocaine HCl, Heroin, Morphine, Nicotine, Alcohol) [28]. | Purity, solubility, and stability in solution are paramount. Dose must be optimized for the species and route. |

| Conditioned Stimuli | Cue lights and tones paired with drug delivery, which acquire motivational properties [28]. | Critical for second-order schedules and cue-induced reinstatement of drug-seeking. |

Signaling Pathways & Neuroadaptations in Compulsive Seeking

Chronic drug self-administration leads to profound changes in brain circuitry. The diagram below illustrates the key neural pathways and adaptations.

Key Neurocircuitry of Addiction

The tables below consolidate key quantitative findings from the literature to aid in experimental design and data interpretation.

Table 1: Neurobiological Markers of Chronic Drug SA

| Adaptation | Drug Class | Brain Region | Measurable Change | Functional Consequence |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ΔFosB Accumulation | Psychostimulants | NAc | ↑ Protein Expression [28] | Persistent transcription, increased relapse vulnerability |

| CREB Activation | Various | NAc | ↑ Phosphorylation [28] | Mediates tolerance & dysphoria during withdrawal |

| GluA2 Upregulation | Psychostimulants | NAc | ↑ AMPA subunit transcription [28] | Enhanced glutamatergic transmission |

| GLT-1 Downregulation | Cocaine | NAc | ↓ Astrocyte transporter [28] | Impaired glutamate clearance, hyperexcitability |

| Dendritic Spine Changes | Psychostimulants | NAc, PFC | ↑ Density & length [28] | Structural plasticity, habit formation |

| Depressants (e.g., Morphine) | NAc, Hippocampus | ↓ Density [28] | Altered structural connectivity |

Table 2: Behavioral Escalation & Model Criteria

| Behavioral Measure | Limited Access (ShA) | Extended Access (LgA) | Relevance to DSM-5 [28] |

|---|---|---|---|

| Drug Intake | Stable over time | Escalates progressively [28] | Loss of control over use |

| Motivation (Breakpoint) | Moderate | Significantly increased [28] | Great deal of time spent to obtain drug |

| Resistance to Punishment | Low | High (persistent use despite adverse consequences) [28] | Use despite physical/psychological problems |

| Cue-Induced Reinstatement | Moderate | Augmented [28] | Craving triggered by cues |

Punishment-based models are critical tools in preclinical research for studying the compulsive dimension of substance use disorders. These paradigms model a core clinical feature of addiction: the persistence of drug-seeking and drug-taking behaviors despite the occurrence of negative consequences. A quintessential method involves challenging an animal's operant responding for a drug, such as cocaine, with the presentation of an adverse stimulus like an electric footshock. This guide details the protocols, troubleshooting, and resources for implementing these models to investigate the neurobiological underpinnings of compulsion-like behavior.

Detailed Experimental Protocol

The following section provides a step-by-step methodology for a punishment-based self-administration experiment, adapted from established models in the field [33].

Animal Subjects

- Species/Strain: Male Wistar rats are commonly used.

- Surgery: Implant with a chronic intravenous jugular catheter to permit intravenous drug delivery.

Cocaine Self-Administration Training

- Apparatus: Standard operant conditioning chambers equipped with at least two nose-poke ports or levers, a house light, and a cue light/tone generator.

- Session Parameters:

- Duration: 1-hour daily sessions.

- Reinforcement Schedule: Fixed-Ratio 3 (FR3). The animal must make three responses on the "active" port to receive a single drug infusion.

- Drug Infusion: A dose of 0.5 mg/kg/infusion of cocaine is standard [34].

- Conditioned Stimulus (CS): Each cocaine infusion is paired with a compound audiovisual stimulus (e.g., activation of a nose-poke light and a tone) for 2-5 seconds.

- Acquisition Criterion: Animals typically must achieve a stable baseline of responding (e.g., >10 infusions per session for 3 consecutive days) before progressing to the punishment phase [34].

Punishment Phase

- Objective: To assess the resilience of drug-seeking behavior when it is paired with a negative outcome.

- Punishment Contingency: A portion (e.g., 30-50%) or all of the drug-paired responses now also result in the delivery of a mild electric footshock to the grid floor of the chamber.

- Footshock Parameters:

- Intensity: Typically escalated across sessions (e.g., from 0.1 mA to 0.9 mA) [33].

- Duration: A brief shock, usually 0.5 seconds.

- Control: It is critical to include a control group that continues to self-administer cocaine without any punishment contingency to control for non-specific changes in behavior over time [35].

Key Behavioral Measures

- Primary Measure: The number of punished responses on the active port compared to baseline and control group levels.

- Suppression Ratio: (Baseline Responses - Punished Responses) / (Baseline Responses + Punished Responses). A higher ratio indicates greater behavioral suppression.

- Inactive Port Responses: Responses in the non-drug-associated port are measured to assess general locomotor activity and non-specific behavioral suppression.

The table below summarizes the quantitative outcomes from a key study investigating how prior experience with intense punishment alters future behavior [33].

| Experimental Phase | Punishment Intensity | Behavioral Outcome | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Initial Punishment | 0.1 mA | Minimal suppression | This intensity is initially ineffective at suppressing well-established drug-taking. |

| Initial Punishment | 0.3 - 0.9 mA | Progressive suppression | Drug-taking decreases as the cost (shock intensity) increases. |

| Post-High-Intensity Experience | 0.1 mA (Retest) | Significant suppression | A previously ineffective shock intensity now potently suppresses drug-taking. |

| Control (Passive Shock) | 0.1 mA (Retest) | Minimal suppression | Mere exposure to shock is insufficient; the contingent experience is critical. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is the critical distinction between "punishment" and other aversive learning paradigms like "fear conditioning"? Punishment is a form of instrumental aversive learning where a specific behavior (e.g., a lever press) causes an aversive event (e.g., footshock). This leads to the formation of a response-outcome (R-O) association that suppresses that specific behavior. In contrast, fear conditioning is a Pavlovian process where a neutral stimulus (a tone) predicts an aversive event, regardless of the animal's behavior, forming a stimulus-outcome (S-O) association that can cause a general, non-specific suppression of behavior like freezing [35]. Conflating these contingencies will confound data interpretation.

Q2: My animals show complete suppression of drug-taking during punishment. Is this a failed experiment? Not necessarily. Complete suppression indicates that the chosen punisher (e.g., footshock intensity) is too high for the reinforcing strength of the drug dose/schedule in your specific setup. To model compulsion, the goal is often to identify the subset of animals that continue to respond. Troubleshooting: Titrate down the shock intensity or increase the drug dose (e.g., by using a progressive ratio schedule prior to punishment) to find a parameter where a bimodal distribution of "suppressors" and "non-suppressors" emerges [35] [33].

Q3: Why is it important to use a "contingent" punishment design rather than just giving animals non-contingent footshocks? The contingency is fundamental. A key study demonstrated that rats that experienced response-contingent high-intensity punishment subsequently became more sensitive to lower punishment intensities. Animals that received the same shocks non-contingently did not show this increased sensitivity [33]. This shows that the learning of the action-consequence relationship is essential for the behavioral adaptation, directly modeling the conflict faced by humans with addiction.

Q4: What neurobiological mechanisms are implicated in punishment resistance? Research points to specific alterations in the mesolimbic dopamine system and associated circuits [34] [36].

- Dopamine: Signaling in the nucleus accumbens core evolves differently based on context. Dopamine to non-contingent drug cues increases, promoting cue reactivity, while dopamine to contingent cues (following a drug-seeking action) decreases, which may disinhibit and promote escalated consumption [34].

- Serotonin: This neurotransmitter is more strongly associated with processing punishments and promoting behavioral inhibition. Pharmacological manipulations of serotonin in humans affect punishment learning and aversive Pavlovian biases [36]. An imbalance between dopamine-driven reward seeking and serotonin-driven punishment avoidance may underlie compulsion.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

The table below catalogues the key resources required to establish a punishment-based self-administration model.

| Item | Function/Description |

|---|---|

| Operant Conditioning Chambers | Sound-attenuating boxes equipped with nose-poke ports/levers, cue lights, tone generators, and a grid floor for delivering scrambled footshock. |

| Footshock Generator | A precision current shock generator capable of delivering a range of mild, scrambled shocks (e.g., 0.1 - 0.9 mA) to prevent animals from avoiding the current. |

| Intravenous Catheter & Infusion Pump | A chronic jugular vein catheter connected to a syringe pump for the precise, automated delivery of intravenous cocaine. |

| Cocaine HCl | The primary reinforcer. Typically dissolved in sterile saline (e.g., 0.9% NaCl) and filtered for self-administration. |

| Fast-Scan Cyclic Voltammetry (FSCV) | An electrochemical technique used in conjunction with carbon-fiber microelectrodes to measure real-time, phasic dopamine release in brain regions like the nucleus accumbens during behavior [34]. |

| Carbon-Fiber Microelectrodes | Implanted bilaterally in the brain (e.g., NAcc core) for FSCV recordings to detect neurotransmitter dynamics [34]. |

Experimental Workflow and Behavioral Outcomes

The following diagram illustrates the key stages and decision points in a typical punishment experiment, culminating in the separation of punishment-sensitive and punishment-resistant individuals.

Diagram 1: Workflow for isolating punishment-resistant individuals.

Signaling Pathways in Compulsive Drug Seeking

This diagram summarizes the opposing roles of mesolimbic dopamine signaling, which vary dramatically depending on whether a drug cue is presented contingent on an action or non-contingently.

Diagram 2: Opposing dopamine pathways in addiction behaviors.

A core challenge in treating drug addiction is the high rate of relapse to drug use after periods of abstinence [37]. In humans, relapse is often triggered by exposure to three primary categories of stimuli: stress, drug-associated cues, and the drug itself (drug priming) [38] [39]. For several decades, preclinical research has sought to understand and mitigate this problem using animal models, predominantly the reinstatement model [40] [39]. This model allows researchers to study the resumption of drug-seeking behavior in laboratory animals following extinction of drug-reinforced responding. The fundamental principle is that after a period of extinction, non-contingent exposure to a stressor, a drug-associated cue, or a small priming dose of the drug can robustly reinstate lever-pressing behavior that was previously associated with drug delivery [39]. This technical support document outlines the core methodologies, neurobiological mechanisms, and common troubleshooting points for these foundational models of relapse, framed within the context of a broader thesis on modeling compulsive drug seeking.

Core Reinstatement Models: Protocols and Mechanisms

The reinstatement model is the most established paradigm for studying relapse-like behavior. The general procedure involves three sequential phases: self-administration training, extinction, and reinstatement testing [39]. The table below summarizes the key characteristics of the primary reinstatement models.

Table 1: Summary of Primary Reinstatement Models

| Model Type | Key Triggering Stimulus | Typical Protocol for Induction | Key Neurobiological Substrates |

|---|---|---|---|

| Drug-Priming-Induced [39] | Non-contingent injection of the previously self-administered drug. | After extinction, a priming injection of the drug (e.g., heroin, cocaine) is administered prior to the test session. | Dopamine receptors (D1, D2) in NAc; Opioid receptors; Glutamate receptors in NAc core [39]. |

| Cue-Induced [39] [41] | Discrete cue (e.g., tone, light) previously paired with drug infusion. | After extinction in the absence of the cue, lever presses during testing once again result in the presentation of the discrete cue. | Basolateral amygdala; Nucleus accumbens core; Ventral tegmental area (VTA) [39] [41]. |

| Stress-Induced [42] | Physical or psychological stressor. | After extinction, a stressor (e.g., intermittent footshock, injection of yohimbine) is administered prior to the test session. | CRF and norepinephrine in BNST and CeA; Dopamine and glutamate in VTA, mPFC, and NAc [42]. |

| Context-Induced [39] | Background environment previously associated with drug availability. | Self-administration in Context A, extinction in Context B, then testing back in Context A. | Ventral hippocampus; Basolateral amygdala; Medial prefrontal cortex [39]. |

Drug-Priming-Induced Reinstatement

Experimental Protocol:

- Training: Animals are trained to self-administer a drug (e.g., cocaine, heroin) by pressing a lever. Each infusion is paired with a discrete cue (e.g., light+tone).

- Extinction: The drug and the associated discrete cue are withheld. Lever presses have no programmed consequence. This phase continues until responding reaches a predetermined low level.

- Reinstatement Test: Under extinction conditions, animals receive a non-contingent, priming injection of the drug or a pharmacologically related compound before the session. Reinstatement is quantified as a significant increase in lever-pressing behavior compared to extinction levels [39].

Troubleshooting FAQ:

- Q: What is an appropriate priming dose for cocaine reinstatement?

- A: Doses are typically in the low-to-moderate range (e.g., 0.5-2.0 mg/kg, i.p. or s.c.) that are sufficient to trigger seeking without producing profound locomotor or sedative effects. A dose-response curve should be established for a new lab setup [39].

Cue-Induced Reinstatement

Experimental Protocol:

- Training: Identical to drug-priming protocols. The discrete cue is critically paired with each drug infusion.

- Extinction: Lever presses are extinguished in the absence of the discrete cue.

- Reinstatement Test: Under extinction conditions (no drug available), lever presses now result in the presentation of the discrete cue alone. The ability of this contingent cue to reinstate lever-pressing is measured [39] [41].

Troubleshooting FAQ:

- Q: How can I ensure my discrete cue acquires robust conditioned reinforcing properties?

- A: Ensure a tight temporal contiguity between cue onset and drug delivery. Use a cue duration that overlaps with the drug infusion. A sufficient number of training sessions (often 10+ days) is required for strong conditioning [41].

Stress-Induced Reinstatement

Experimental Protocol:

- Training & Extinction: Conducted as in the other models.

- Reinstatement Test: Prior to the test session, animals are exposed to a stressor. The most common are:

- Intermittent Footshock: Typically, a series of brief, unpredictable footshocks (e.g., 0.5-1.0 mA, 0.5-1.0 sec duration) delivered over a period (e.g., 15 minutes) [42].

- Pharmacological Stressors: Systemic administration of the α2-adrenergic receptor antagonist yohimbine (e.g., 1.25-2.5 mg/kg, i.p.), which induces a stress-like state by increasing noradrenaline release [42]. Reinstatement is then measured under extinction conditions.

Troubleshooting FAQ:

- Q: My stress-induced reinstatement is inconsistent. What could be wrong?

- A: Stress-induced reinstatement is highly dependent on the specific stressor and drug class. Not all stressors are effective. Footshock and yohimbine are the most reliable. Ensure stressor parameters are calibrated correctly and that animals are not habituated to the stress context [42].

Beyond Extinction: Emerging Models of Voluntary Abstinence

A significant development in the field is the creation of models where abstinence is voluntary rather than experimenter-imposed via extinction. This is considered to have greater translational relevance to human addiction, where abstinence is often self-initiated [43] [44].

Table 2: Models of Relapse after Voluntary Abstinence

| Model | Method to Induce Voluntary Abstinence | Relapse Test | Key Advantage |

|---|---|---|---|

| Adverse Consequences [44] | Introducing a negative consequence to drug taking (e.g., footshock punishment) or seeking (e.g., an electric barrier). | Exposure to drug cues, priming, or stress. | Models the clinical scenario where users quit due to negative repercussions. |

| Discrete Choice [43] [44] | Providing mutually exclusive choices between a drug and a palatable food reward. Rats consistently choose food, leading to voluntary abstinence. | Exposure to drug cues or stress after a period of choice-induced abstinence. | Incorporates the role of alternative, non-drug rewards in maintaining abstinence, akin to contingency management in humans. |

Neurobiological Pathways of Relapse

Understanding the neural circuitry of relapse is essential for target identification. The following diagrams summarize the key brain regions and neurochemical systems implicated in different forms of reinstatement.

Core Reinstatement Circuitry

Diagram 1: Neural circuitry of different relapse triggers. Key: BLA (Basolateral Amygdala); NAc (Nucleus Accumbens); VTA (Ventral Tegmental Area); BNST (Bed Nucleus of Stria Terminalis); CeA (Central Amygdala); vmPFC (ventromedial Prefrontal Cortex); DA (Dopamine); CRF (Corticotropin-Releasing Factor).

The Orexin System in Stress and Cue-Induced Relapse

Recent research has highlighted the role of the orexin (hypocretin) system, originating in the lateral hypothalamus (LH), in regulating relapse behaviors, particularly in response to stress and drug cues [45].

Diagram 2: The orexin pathway in relapse. Orexin neurons in the LH project to key regions like the posterior paraventricular nucleus of the thalamus (pPVT), VTA, and BNST. Blocking orexin receptors (OXR) in the pPVT with an antagonist like suvorexant can selectively prevent stress-induced reinstatement of drug seeking [45].

Table 3: Key Research Reagents for Relapse Studies

| Reagent / Resource | Function / Target | Example Use in Relapse Models |

|---|---|---|

| Yohimbine | α2-adrenergic receptor antagonist | Induces a stress-like state to provoke stress-induced reinstatement of drug seeking [42]. |

| Suvorexant (SUV) | Dual Orexin Receptor (OXR) Antagonist | Used to probe the role of the orexin system; e.g., intra-pPVT infusion blocks stress-induced reinstatement of oxycodone seeking [45]. |

| Naltrexone | Opioid receptor antagonist | Reduces drug-priming-induced and cue-induced reinstatement for heroin and alcohol [39]. |

| Daun02 Chemogenetic Procedure | Inactivation of behaviorally activated neuronal ensembles | Used in Fos-lacZ transgenic rats to ablate specific neuronal ensembles encoding drug-cue memories, preventing context-induced relapse [44]. |

| DREADDs (Designer Receptors Exclusively Activated by Designer Drugs) | Chemogenetic excitation or inhibition of specific neural pathways | The retro-DREADD approach allows selective manipulation of defined neuronal projections to dissect their role in relapse circuits [44]. |

The reinstatement model has been an invaluable tool for unraveling the neuropharmacological basis of relapse [38]. However, the field is evolving. Future research must continue to bridge the gap between traditional extinction-based models and newer paradigms that incorporate voluntary abstinence driven by adverse consequences or the availability of alternative rewards [43] [44]. Furthermore, while the orexin system represents a promising target, particularly for stress-induced relapse [45], a critical challenge remains: the neuropharmacological mechanisms controlling relapse after voluntary abstinence can differ from those controlling reinstatement after extinction [44]. This underscores the necessity of using multiple, complementary models to fully understand the complex phenomenon of relapse and to develop effective, translationally relevant pharmacotherapies for its prevention.

Troubleshooting Guides & FAQs

FAQ: Behavioral Modeling & Experimental Design

Q: What are the core behavioral criteria for modeling compulsive drug seeking in animals? A: Compulsive drug seeking, a hallmark of addiction, is operationally defined in animal models through specific behavioral manifestations. Key criteria include escalation of drug intake with extended access, increased motivation for the drug as measured by progressive ratio schedules, persistence of drug seeking despite adverse consequences (e.g., punishment), and preference for drug over natural rewards like food or social interaction [46] [47]. These criteria translate DSM-IV diagnostic criteria for substance use disorder into quantifiable experimental measures [46].

Q: How can I determine if drug-seeking behavior has become a "habit" in my experiments? A: The gold-standard test for habitual (stimulus-response) behavior is outcome devaluation [48] [49]. In a goal-directed state, animals will reduce drug-seeking efforts if the drug outcome is devalued (e.g., by pairing it with an aversive stimulus like lithium chloride-induced malaise). If drug seeking persists despite devaluation, the behavior is classified as a habit. Neurobiologically, this transition from goal-directed to habitual drug seeking is associated with a shift in neural control from the ventral striatum (e.g., nucleus accumbens) to the dorsal striatum [48] [49].

Q: Why do only a subset of animals typically develop compulsive phenotypes in my studies? A: Individual vulnerability is a key feature of addiction. Pre-existing behavioral traits, such as high impulsivity, predict a greater propensity to escalate drug intake and develop compulsive drug seeking [48] [49]. These traits are linked to individual differences in neurobiology, such as low dopamine D2/3 receptor levels in the nucleus accumbens [49]. Using outbred rodent populations and including measures of impulsivity or other traits as co-variables in your experimental design can help account for this heterogeneity.

Q: My drug and natural reward seeking data are highly variable. Which brain circuits are selectively involved in drug seeking? A: While drug and natural rewards activate overlapping brain circuits, causal studies reveal a drug-selective circuit [50]. The table below summarizes key regions and their necessity for drug versus natural reward seeking.

Table: Necessity of Brain Regions for Drug vs. Natural Reward Seeking

| Brain Region | Necessity for Drug Reward Seeking | Necessity for Natural Reward Seeking |

|---|---|---|

| Nucleus Accumbens Core (NAcore) | Drug-Selective [50] | Not Necessary [50] |

| Prelimbic Cortex (PL) | Drug-Selective [50] [47] | Not Necessary [50] |

| Ventral Tegmental Area (VTA) | Drug-Selective [50] | Not Necessary [50] |

| Central Amygdala (CeA) | Drug-Selective [50] | Not Necessary [50] |

| Basolateral Amygdala (BLA) | Shared [50] | Necessary [50] |

| Hippocampus (HIPP) | Shared [50] | Necessary [50] |

FAQ: Technical & Measurement Challenges

Q: How does cue contingency affect the dopamine signals I'm measuring in the NAcc? A: The context of cue presentation critically determines the direction of phasic dopamine signaling in the Nucleus Accumbens Core (NAcc) [34]. Non-contingent cue presentation (outside the drug-taking context) elicits a craving-like state and dopamine signals increase with extended drug use. Conversely, contingent cue presentation (as a feedback signal for a drug-taking action) is linked to drug "satiety" and its evoked dopamine signal decreases in animals that escalate consumption [34]. These diametrically opposed dopamine trajectories can occur concurrently in the same animal.

Q: What are the best practices for modeling the choice between drug and natural rewards? Q: What are the best practices for modeling the choice between drug and natural rewards? A: Modern paradigms move beyond simple self-administration to incorporate conflict and choice. Effective methods include:

- Concurrent Choice Schedules: Animals choose between a drug-associated lever and a natural reward (e.g., food or sucrose)-associated lever. Compulsion is indicated by a persistent preference for the drug despite the availability of a palatable alternative [46] [50].

- Punishment-Based Conflict: Animals must overcome an aversive consequence (e.g., footshock) to obtain the drug. Resistance to punishment is a direct model of compulsive use despite negative consequences [46] [47].

- Behavioral Economic Procedures: These models assess the relative value of a drug by evaluating consumption as a function of price (response requirement), revealing demand elasticity and its differences from natural rewards.

Experimental Protocols & Methodologies

Protocol: Second-Order Schedule of Reinforcement for Studying Drug Seeking

Purpose: To dissociate the neural mechanisms of drug seeking (appetitive behavior) from drug taking (consummatory behavior) and to study the powerful influence of drug-associated cues [48] [49].

Workflow:

Procedure:

- Acquisition: Animals are first trained to self-administer a drug (e.g., intravenous cocaine) on a simple continuous reinforcement schedule (Fixed Ratio 1, or FR1), where each active lever press results in a drug infusion paired with a conditioned stimulus (CS) [48].

- Second-Order Schedule: Once behavior is stable, a second-order schedule is introduced (e.g., FR10 (FI 15min:S)). In this schedule:

- The animal must complete 10 responses on the active lever (FR10) to produce the drug-associated CS.

- The first response after a 15-minute fixed interval (FI 15min) has elapsed results in both the CS and the drug infusion.

- This means the animal works for an extended period (e.g., 15 minutes) where the only "reward" is the presentation of the drug-paired CS, which acts as a conditioned reinforcer to maintain seeking behavior [48] [49].

- Measurement: The primary dependent variable is the number of responses during the seeking (FI) interval. This paradigm allows for the separate analysis of cue-maintained seeking behavior and the final consummatory act of drug taking.

Protocol: Punishment-Resistance Model of Compulsive Seeking

Purpose: To model the core clinical feature of addiction—continued drug use despite negative consequences [46] [47].

Workflow:

Procedure:

- Extended Access: Animals are given prolonged access to the self-administered drug (e.g., 6 hours or more daily for cocaine). This extended history is critical for inducing the neuroadaptations necessary for a compulsive phenotype to emerge in a subset of animals [46] [47].

- Punishment Contingency: In probe sessions, a punishment is introduced. For example, a percentage (e.g., 30-50%) of drug infusions are paired with a mild footshock. Alternatively, seeking responses can be punished.

- Phenotype Classification: Animals are classified based on their behavior:

- Punishment-Sensitive: Animals that significantly suppress their drug seeking.

- Punishment-Resistant (Compulsive): Animals that continue to seek and take the drug despite the adverse consequence. This resistance is linked to prelimbic cortex (PL) hypofunction [47].

Protocol: Choice-Based Paradigm for Drug vs. Natural Reward

Purpose: To quantify the relative value of a drug reward compared to a natural reward and model the clinical symptom where drug use supersedes important social and occupational activities [46] [50].

Procedure:

- Training: Animals are trained to self-administer a drug (e.g., heroin, cocaine) and separately to self-administer a natural reward (e.g., a palatable sucrose solution).

- Choice Testing: Animals are presented with a choice between two levers or nose-poke ports: one leading to the drug and the other to the natural reward. This can be done after a period of forced abstinence to measure "incubation of craving" for each reward type [50].

- Measurement: The primary measure is the percentage of choices for the drug over the natural reward. Escalated and compulsive drug use is associated with a persistent preference for the drug even when a high-value natural reward is available. Studies using this paradigm have helped identify the circuitry selectively necessary for drug seeking but not natural reward seeking [50].

Quantitative Data Synthesis

Table: Key Behavioral Metrics in Animal Models of Addiction

| Behavioral Metric | Experimental Measure | Interpretation & Significance |

|---|---|---|

| Escalation of Intake | Increased daily drug consumption over time with long-access (LgA, 6+ hrs) but not short-access (ShA, 1 hr) self-administration [46]. | Models transition from controlled use to loss of control over intake. |

| Increased Motivation | Elevated breakpoint under a progressive ratio (PR) schedule, where the response requirement for each subsequent infusion increases [46]. | Reflects increased effort an animal is willing to expend to obtain the drug. |

| Punishment Resistance | Persistence of drug seeking when a probability (e.g., 30-50%) of footshock punishment is delivered contingent on drug infusion [46] [47]. | Core model of compulsive drug use despite negative consequences. |