Maximizing Signal-to-Noise Ratio in Electrophysiology: A Comprehensive Guide from Foundations to Future Tech

Achieving a high signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) is fundamental for obtaining reliable and publication-quality data in electrophysiology, impacting everything from basic neuroscience research to cardiac studies and drug discovery.

Maximizing Signal-to-Noise Ratio in Electrophysiology: A Comprehensive Guide from Foundations to Future Tech

Abstract

Achieving a high signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) is fundamental for obtaining reliable and publication-quality data in electrophysiology, impacting everything from basic neuroscience research to cardiac studies and drug discovery. This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals, detailing the core principles of SNR, practical methodologies for its improvement across various recording setups, systematic troubleshooting of common noise issues, and advanced techniques for validating and comparing recording technologies. By integrating foundational knowledge with cutting-edge applications, this resource aims to equip scientists with the strategies needed to enhance data fidelity, streamline experimental workflows, and accelerate biomedical innovation.

Understanding Signal-to-Noise Ratio: The Bedrock of Quality Electrophysiology

What is SNR? Defining the Core Metric for Data Fidelity

Table of Contents

- What is SNR?

- How is SNR Calculated?

- A Researcher's Guide to Interpreting SNR

- Troubleshooting Low SNR in Electrophysiology

- Experimental Protocol: Quantifying SNR in Cortical Recordings

- Research Reagent Solutions

What is SNR?

Signal-to-Noise Ratio (SNR or S/N) is a fundamental metric in science and engineering that compares the level of a desired signal to the level of background noise [1] [2]. It is a measure of signal clarity and quality.

- Signal: Meaningful information, such as a neural action potential or a specific chemical signature [2].

- Noise: Any unwanted disturbance that interferes with the signal, such as electrical interference from equipment or random thermal activity [3] [2].

A high SNR indicates a clear, strong signal where the meaningful information is easily distinguished from the background noise. A low SNR means the signal is weak or obscured by noise, making it difficult to detect or interpret [1] [2]. In electrophysiology, a high SNR is crucial for accurately representing biological events [3].

How is SNR Calculated?

SNR can be represented as a simple ratio or in logarithmic decibels (dB), which is more common for comparing large value ranges [1] [2].

Formulas for Calculating SNR

| Measurement Type | Formula | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Power Ratio (Linear) | ( SNR = \frac{P{signal}}{P{noise}} ) | (P) represents average power. Both must be measured at the same point in the system and within the same bandwidth [1]. |

| Voltage/Amplitude Ratio (Linear) | ( SNR = \left(\frac{A{signal}}{A{noise}}\right)^2 ) | (A) is the Root Mean Square (RMS) amplitude (e.g., RMS voltage). This is used when measuring voltages across the same impedance [1]. |

| Decibels (dB) from Power | ( SNR{dB} = 10 \log{10}\left(\frac{P{signal}}{P{noise}}\right) ) | The most common expression of SNR. A ratio of 100:1 equals 20 dB [1] [2]. |

| Decibels (dB) from Amplitude | ( SNR{dB} = 20 \log{10}\left(\frac{A{signal}}{A{noise}}\right) ) | Equivalent to ( SNR{dB} = A{signal,dB} - A_{noise,dB} ) [1]. |

| Alternative Definition (Statistics) | ( SNR = \frac{\mu}{\sigma} ) | Here, (\mu) is the mean of the signal or measurement, and (\sigma) is its standard deviation. This defines SNR as the reciprocal of the coefficient of variation [1]. |

A Researcher's Guide to Interpreting SNR

The table below provides a general guide to interpreting SNR values. Specific thresholds for "good" SNR can vary by application and experimental setup.

SNR Interpretation Guide (with examples from Wi-Fi communications)

| SNR (in dB) | Interpretation | Typical Signal Quality |

|---|---|---|

| < 10 dB | Unusable | Noise overpowering the signal [4]. |

| 10 - 15 dB | Poor / Barely There | Frequent dropouts, unreliable for data [4]. |

| 15 - 25 dB | Marginal / Fair | Slow but functional; may have errors [4]. |

| 25 - 40 dB | Good | Reliable for most purposes [4]. |

| > 40 dB | Excellent | High-quality, ideal for demanding applications [4]. |

In contexts like audio engineering, an SNR of 90 dB or more is indicative of high-fidelity sound reproduction [2]. For medical imaging, a higher SNR means more detailed images with higher contrast, facilitating the detection of abnormalities [2].

Troubleshooting Low SNR in Electrophysiology

FAQ: My electrophysiology recordings are noisy. How can I improve the SNR?

Low SNR is a common challenge. The following flowchart outlines a systematic approach to troubleshooting.

FAQ: What are the signatures of common noise types?

| Noise Signature | Potential Source | Corrective Action |

|---|---|---|

| 60/50 Hz Peaks (Mains Hum) | Ground loops, poor shielding of Faraday cage, unshielded power cables near preparation [3]. | Verify single-point grounding; check Faraday cage continuity; move power supplies away [3]. |

| High-Frequency Hash | Radiofrequency interference (RFI) from cell phones, wireless routers, or instrumental chatter [3]. | Ensure Faraday cage is fully sealed; use a wider-band low-pass filter [3]. |

| Slow, Baseline Drift | Thermal noise from amplifier warm-up, slow electrode-electrolyte shifts, or temperature variations [3]. | Allow equipment to warm up; use a high-pass filter digitally; stabilize temperature control [3]. |

| Excessively Large Noise | A broken connection to the ground or reference electrode, or amplifier saturation (clipping) [3]. | Check all electrode and headstage connections; reduce the gain setting on the amplifier [3]. |

Experimental Protocol: Quantifying SNR in Cortical Recordings

This protocol is adapted from a study that developed a new method to calculate the SNR of neural signals across different frequency bands using the features of cortical slow oscillations [5].

Aim: To quantify the SNR of brain recording devices using spontaneous slow oscillations in cerebral cortex recordings.

Background: Slow oscillations (SO), a pattern of neural activity common during slow-wave sleep and under anesthesia, consist of alternating Up states (periods of neuronal firing, considered the "signal") and Down states (periods of neuronal silence, considered the "noise") [5]. This pattern is ideal for SNR calculation as it encompasses a broad frequency band.

Methodology:

- Preparation: Obtain extracellular local field potential (LFP) recordings from active cortical slices that spontaneously generate slow oscillations using a Multielectrode Array (MEA) [5].

- Segmentation: Identify and segment the recording into multiple Up states (N) and Down states (N') [5].

- Spectral Analysis: For each Up state and Down state, calculate the Power Spectral Density (PSD). The PSD shows the power of the signal as a function of frequency [5].

- Averaging: Calculate the average PSD for all Up states and the average PSD for all Down states [5].

- SNR Calculation: Compute the spectral SNR in decibels (dB) using the following formula [5]: ( SNR(f){dB} = 10 \log{10} \left[ \frac{ \frac{1}{N} \sum{i=1}^{N} (PSD{Up})i }{ \frac{1}{N'} \sum{j=1}^{N'} (PSD{Down})j } \right] )

This method provides a rich profile of the recording device's performance across different frequency bands (e.g., 5–1500 Hz), which is crucial for capturing both LFPs and multi-unit activity (MUA) [5].

Research Reagent Solutions

The following table details key materials and their functions as used in the featured experimental protocol for quantifying SNR in cortical recordings [5].

| Item | Function in the Experiment |

|---|---|

| Multielectrode Arrays (MEAs) | Devices used to record electrophysiological signals simultaneously from different neuronal populations in the cortical slice [5]. |

| Platinum Black (Pt) Electrodes | Electrode coating with a high active surface area, leading to lower impedance and better recording performance (higher SNR) compared to plain gold, especially across a wide frequency range [5]. |

| Carbon Nanotube (CNT) Electrodes | Composite electrode material that provides a large active surface area, resulting in low impedance and high SNR, performing comparably to Platinum Black [5]. |

| Gold (Au) Electrodes | A standard metallic conductor for electrodes. Without surface treatments to increase area, it typically exhibits higher impedance and lower SNR compared to Pt or CNTs [5]. |

| Specialized Bioamplifier | Amplifies minuscule biological potentials. Requires high input impedance (e.g., on the order of TΩ) and a high Common-Mode Rejection Ratio (CMRR >100 dB) to maximize the true biological signal and reject environmental noise [3] [5]. |

In electrophysiology research, the Signal-to-Noise Ratio (SNR) is a fundamental quantitative measure that compares the power of a target neural signal to the power of background noise. A high SNR is not merely a technical prerequisite for clean data; it directly determines the reliability of subsequent analyses and the validity of scientific conclusions. Its importance extends to two critical theoretical domains: it sets the upper limit for stimulus discriminability (d') according to signal detection theory and fundamentally constrains the mutual information between a stimulus and a neural response as defined by information theory. This technical resource center elaborates on these relationships and provides actionable protocols for researchers aiming to optimize SNR in their experimental workflows, thereby enhancing the quality and interpretability of their electrophysiological data.

Theoretical Foundations: SNR, Discriminability, and Information

Quantitative Definitions and Relationships

The core relationships between SNR, discriminability (d'), and mutual information (I) provide a mathematical foundation for understanding neural coding reliability.

Table 1: Core Quantitative Relationships Between SNR, Discriminability, and Information

| Concept | Mathematical Definition | Interpretation in Neuroscience |

|---|---|---|

| Signal-to-Noise Ratio (SNR) | (\frac{PS}{PN} = \frac{E[rs^2]}{\sigmaN^2}) [6] | Quantifies the strength of a stimulus-evoked response ((PS)) relative to trial-to-trial response variability ((PN)). |

| Discriminability (d') | (d' = \frac{\Delta r}{\sigma_N}) [6] | Measures the ability of an ideal observer to discriminate between two stimuli based on the neural response; directly related to SNR. |

| Mutual Information (I) | (I = \frac{1}{2} \log_2 (1 + SNR)) [6] | For Gaussian signals and noise, measures the amount of information (in bits) the neural response carries about the stimulus. |

The relationship between SNR and discriminability is direct and quantitative: (\SNR = (d')^2) [6]. This means that a doubling of the d' value implies a quadrupling of the required SNR. This relationship translates into a direct impact on performance in a detection task. The probability of correct detection ((PC)) in a simple signal detection task is given by ( PC = \phi(d'/2) ), where (\phi) is the cumulative normal distribution function [6]. When the SNR reaches a value of 1, the corresponding d' is also 1, and the probability of correct detection is approximately 69%, a common threshold for detection in psychophysics [6].

Table 2: Relationship Between SNR, d', and Probability of Correct Detection

| SNR | Discriminability (d') | Probability of Correct Detection ((P_C)) |

|---|---|---|

| 0 | 0 | 50% (Chance Level) |

| 0.25 | 0.5 | 60% |

| 1.00 | 1.0 | ~69% (Common Detection Threshold) |

| 4.00 | 2.0 | 84% |

| 9.00 | 3.0 | 93% |

The Interplay of Measures in Practice

Different measures of reliability can lead to different interpretations of the same data. A study on blowfly photoreceptors demonstrated that even when the SNR was well below 1, a signal-detection analysis ((d')) could safely discriminate responses to weak stimuli [7]. In contrast, information-theoretical measures like the Shannon information capacity and Kullback-Leibler divergence indicated very low performance for the same low-contrast stimuli, showing a marked increase only at higher contrasts [7]. This highlights that no single measure provides a complete picture, and the choice of measure should align with the specific scientific question.

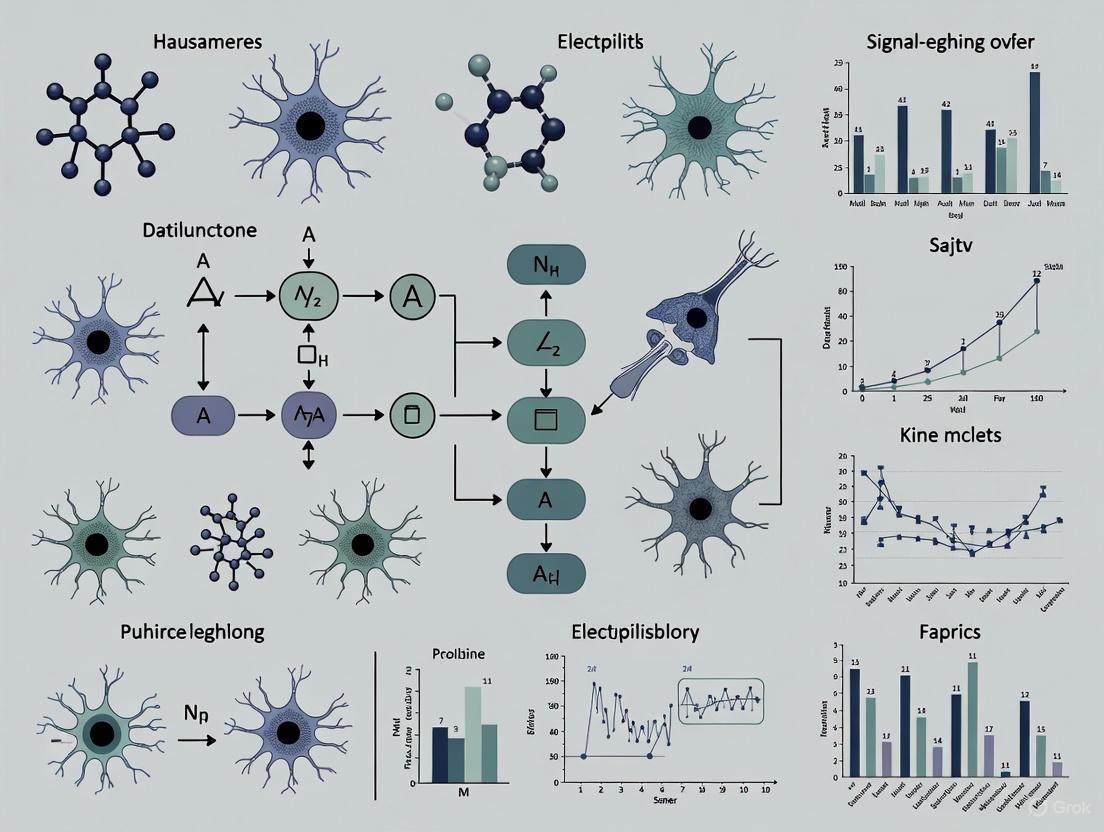

Figure 1: The central role of Signal-to-Noise Ratio (SNR) in determining two key properties of neural coding: Discriminability and Mutual Information.

Troubleshooting Guides & FAQs

Diagnosing and Solving Common Noise Problems

Table 3: Troubleshooting Common Noise Sources in Electrophysiology Recordings

| Noise Signature | Most Likely Cause | Corrective Actions |

|---|---|---|

| Large-amplitude, wide-band noise, strong 50/60 Hz peak [8] | Floating ground or reference wire (loose or broken connection) [8] | Check continuity of all ground/reference connections. Ensure headstage is functioning. Use the headstage's "grounded referencing" mode if necessary [8]. |

| Prominent 50/60 Hz "hum" [3] [8] | Ground loops (current flow between equipment with different ground potentials) [8] | Connect all equipment to a single power outlet. Tie chassis grounds of all equipment (e.g., stimulators) to the subject ground. Use a medical-grade isolation transformer [3]. |

| High-frequency "hash," intermittent RF spikes [3] [8] | RF/EMI from lights, power supplies, motors, cell phones, WiFi [8] | Turn off lights and unnecessary electronics. Use short, shielded cables. Move setup away from power lines. Use a properly grounded Faraday cage [3] [8]. |

| Slow, large-amplitude baseline drift [3] | Thermal noise from equipment warm-up, unstable electrode-electrolyte interface [3] | Allow amplifiers to warm up for 30+ minutes. Ensure stable temperature control. Use a high-pass filter during analysis (with caution) [3]. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: My recordings show significant 60 Hz noise. I've checked my grounding, and it seems correct. What should I try next? A: First, perform a spectral analysis to confirm the noise is at 60 Hz and its harmonics. If grounding is confirmed, the next most common cause is electromagnetic interference (EMI). Try turning off overhead lights, particularly fluorescent ones with ballasts, and relocate power supplies and computers away from your recording setup. If the problem persists, a notch filter can be applied digitally as a last resort, though it may introduce ringing artifacts [3] [8].

Q2: How can I objectively measure the SNR in my recorded neural data? A: For discrete stimulus conditions, SNR can be calculated as the ratio of the power of the average evoked response (the signal) to the variance of the responses across trials (the noise) [6]. For continuously varying stimuli, the power spectral density of the mean response ((PS(f))) and the trial-to-trial fluctuations ((PN(f))) are computed. The SNR at each frequency is then (SNR(f) = PS(f)/PN(f)), and the overall SNR is the ratio of the total power under these curves [6].

Q3: Why might my data have a good visual SNR but still yield low mutual information estimates? A: Information-theoretical measures like mutual information are sensitive to the entire distribution of responses and not just the mean signal power. Your neural response might be reliable (high SNR for the average) but lack variability across different stimuli, which limits the total information capacity. As per the formula (I = \frac{1}{2} \log_2 (1+SNR)), mutual information increases logarithmically with SNR, meaning that substantial increases in information require exponentially larger improvements in SNR [6] [7].

Q4: What is the simplest hardware modification to improve SNR? A: Ensuring a proper differential amplification setup with a high Common-Mode Rejection Ratio (CMRR) is paramount. This involves using an active electrode, a reference electrode, and a high-quality amplifier that subtracts noise common to both inputs (like 60 Hz line noise). A CMRR exceeding 100 dB is recommended for rejecting pervasive environmental interference [3].

Experimental Protocols for SNR Enhancement

Protocol: Signal Averaging for Evoked Potentials

Application: Enhancing the SNR of time-locked neural responses, such as auditory brainstem responses (ABRs) or cortical auditory evoked potentials (CAEPs) [9] [3].

Detailed Methodology:

- Stimulation: Present a discrete stimulus (e.g., a tone burst or speech syllable like /da/) repeatedly for hundreds or thousands of trials [9] [10].

- Recording: Record the neural response (e.g., EEG) within a time window aligned to each stimulus onset.

- Alignment and Averaging: Preprocess the data from each trial (e.g., band-pass filtering) and then compute the average waveform across all trials.

- Principle: The time-locked neural signal remains consistent across trials, while the background neural and instrumental noise is random and uncorrelated. Averaging causes the noise to sum towards zero, while the signal reinforces itself.

- SNR Improvement: The SNR improves proportionally to the square root of the number of trials (N) averaged. Therefore, to double the SNR, you need to quadruple the number of trials [3].

Figure 2: Workflow for Signal Averaging. Averaging across N trials improves SNR proportionally to the square root of N.

Protocol: Calculating Neural SNR for Speech-in-Noise Experiments

Application: This objective measure, derived from cortical auditory evoked potentials (CAEPs), captures an individual's ability to neurally segregate target speech from background noise and has been shown to predict behavioral performance and hearing aid outcomes [9].

Detailed Methodology:

- Stimuli and Task: Present target speech (e.g., monosyllabic words) embedded in background noise (e.g., speech-shaped noise) to participants while recording EEG [9].

- Component Extraction: Calculate the cortical auditory evoked responses to two key events:

- Response to Noise Onset (N): The amplitude of the CAEP following the onset of the background noise alone.

- Response to Speech Onset (S): The amplitude of the CAEP following the onset of the target speech, which is presented after the noise has already begun [9].

- Calculation: The neural SNR is computed as the ratio: (Neural\ SNR = \frac{Response\ to\ Speech\ Onset\ (S)}{Response\ to\ Noise\ Onset\ (N)}) [9].

- Interpretation: A higher neural SNR indicates more robust neural representation of the target speech relative to the background noise, reflecting efficient noise suppression. This single neural index correlates with behavioral speech-in-noise perception and can be used to assess the efficacy of noise-reduction algorithms [9].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

Table 4: Key Materials and Equipment for High-SNR Electrophysiology

| Item | Specification / Purpose | Key Function |

|---|---|---|

| Instrumentation Amplifier | High CMRR (>100 dB), High Input Impedance (>1 GΩ) [3] | Performs differential amplification to reject common-mode environmental noise while faithfully amplifying the tiny biological signal. |

| Faraday Cage | Properly grounded conductive mesh or solid enclosure [3] [8] | Shields the preparation and headstage from external electromagnetic interference (EMI) and radio frequency interference (RFI). |

| Active Electrodes / Headstage | Placed as close to the signal source as possible [3] [8] | The first amplification stage converts high-impedance signals from the electrode to a low-impedance signal, minimizing noise pickup in the cable. |

| Shielded, Twisted-Pair Cables | As short as practically possible [8] | Minimizes capacitive and inductive coupling of noise from power lines and other equipment. |

| Digital Headstage | Converts analog signal to digital at the source [8] | Renders the signal immune to noise that can be picked up in the cable running from the headstage to the main acquisition unit. |

Troubleshooting Guides

Guide 1: Identifying and Eliminating Line Noise (50/60 Hz)

Problem: A persistent, sinusoidal hum at 50 Hz or 60 Hz (and their harmonics) is overwhelming your recording signal.

Background: This line noise, or "mains hum," originates from the AC power grid and is the most common interference in electrophysiology labs. It can be caused by electromagnetic fields from power lines, equipment, or lighting, and is often amplified by ground loops [11] [8].

Methodology:

- Diagnose with Spectral Analysis: Use your system's real-time spectrograph to confirm a strong peak at 50/60 Hz [8].

- Inspect Grounding: Check for a "floating ground" caused by a broken or loose ground wire. Verify all connections. Use a continuity tester to ensure a stable, low-impedance path to ground [8].

- Eliminate Ground Loops: Implement a single-point "star-grounding" system where all rig components are connected to one central ground point. Plug all equipment into the same master power strip to consolidate ground pathways [3] [11].

- Check Shielding: Ensure your Faraday cage is properly sealed and connected to the single earth ground reference. Keep the headstage and electrode as far as possible from power supplies and cables [3].

- Use Specialized Hardware: As a last resort, employ a driven shield/guard technology on your amplifier or a dedicated device like a HumBug Noise Eliminator to remove line frequency noise in real-time [11].

Guide 2: Reducing High-Frequency and Intermittent Noise

Problem: The recording shows high-frequency "hash" or intermittent spiky noise.

Background: This noise typically comes from Radio-Frequency Interference (RFI) or Electromagnetic Interference (EMI) sources like cell phones, WiFi routers, fluorescent light ballasts, or electric motors [3] [8].

Methodology:

- Identify the Source: Turn off or remove potential sources one by one. Start with cell phones, WiFi routers, and unused electronics [12] [8].

- Improve Shielding: Ensure the Faraday cage is fully sealed. Use shielded, twisted-pair cables for all signal transmission [3].

- Apply Filtering: Set the amplifier's low-pass filter just above the highest frequency component of your biological signal to attenuate extraneous high-frequency noise [3].

- Check Cable Management: Avoid running signal cables parallel to power lines. Use short headstage cables and avoid looping excess cable, which can act as an antenna [8].

Guide 3: Resolving Unstable Recordings and Drift

Problem: The recording baseline is unstable, drifting slowly, or the pipette tip drifts after seal formation.

Background: Slow drift can be caused by temperature fluctuations, electrode instability, or poor pressure control. Pipette drift is often mechanical [3] [12].

Methodology:

- Stabilize Temperature: Allow the amplifier to warm up for at least 30 minutes before recording. Ensure the recording chamber temperature is controlled [3].

- Check Pipette Holder: Pipette drift is commonly caused by an over-tightened or under-tightened electrode holder cap compressing the O-ring. Apply a small amount of grease to the O-ring to release strain and ensure the holder is correctly tightened [12].

- Secure the Setup: Ensure nothing is touching the pipette and that the pressure tube and headstage cable are secured to prevent strain on the electrode holder [12].

- Apply Digital Filtering: Use a digital high-pass filter to remove very slow baseline drift caused by temperature changes or electrode instability, but avoid distorting relevant slow biological signals [3].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q: I've formed a gigaohm seal, but the cell seems dead immediately after breaking in. What happened? A: The cell was likely dead before patching. Review your cell selection criteria and check the health of your brain slices. Ensure your artificial cerebrospinal fluid (ACSF) is properly oxygenated with carbogen and has the correct pH [12].

Q: My series resistance starts out low but increases during the experiment. Why? A: This is usually a sign that the pipette tip is becoming clogged or the cell membrane is resealing. Applying a small amount of pressure or suction can sometimes reopen the tip. Using pipettes with a larger tip diameter can help prevent this [12].

Q: There is a loud, wide-band noise across all my channels. What should I check first? A: This is a classic symptom of a floating ground or reference. Check all ground and reference connections for breaks or loose wires. This should always be your first step when troubleshooting severe, channel-wide noise [8].

Q: My recordings are contaminated by large, sharp artifacts. What could cause this? A: This is often a movement artifact. In behaving animals, it can be caused by myogenic (muscle) noise from chewing, or by physical movement of the headstage cable or connectors. Using a commutator and ensuring the headstage cable is not too long can help [8]. Also, ensure cell phones are turned off, as they can cause intermittent spiky noise [12].

Experimental Protocols for Noise Optimization

Protocol 1: Signal Averaging for Evoked Potentials

Application: Enhancing the signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) of time-locked responses, such as somatosensory evoked potentials (SEPs), which are buried in random, uncorrelated noise [3].

Detailed Methodology:

- Stimulation: Deliver a precise, repetitive stimulus (e.g., electrical shock to a peripheral nerve).

- Recording: Record the electrophysiological response for a fixed time window following each stimulus. Each recording is called a "sweep" or "trial."

- Alignment and Averaging: Align all recorded sweeps based on the time of stimulus onset and calculate the average signal across all sweeps.

- Principle: The time-locked evoked signal remains constant across trials and is reinforced by averaging. In contrast, the random noise components tend to cancel each other out. The SNR improves proportionally to the square root of the number of averaged trials [3].

Key Research Reagent Solutions:

| Item | Function |

|---|---|

| Constant-Current Stimulator | Delivers precise, isolated electrical pulses to the nerve without introducing artifact. |

| Shielded Stimulation Electrodes | Prevents the stimulation artifact from coupling into the recording electrodes. |

Optimization Data: A 2023 study systematically optimized SEP recordings by varying the stimulation rate. It found that for short-duration median nerve SEP recordings, a stimulation rate of 12.7 Hz achieved the highest SNR (22.9 for the N20 component at 5 seconds recording duration), outperforming lower rates like 4.7 Hz. This demonstrates that for short recordings, the benefit of rapid noise reduction through more averaging at a higher rate can outweigh the disadvantage of smaller signal amplitude [13].

Protocol 2: Advanced Algorithmic Noise Cancellation

Application: Removing persistent, structured noise like cardiac artifacts from electrospinography (ESG) or other recordings, especially when traditional averaging or filtering is unsuitable [14].

Detailed Methodology: A 2025 systematic comparison evaluated five denoising algorithms for removing cardiac artifacts from spinal cord recordings [14]:

- Principal Component Analysis (PCA): Effective when a limited number of electrodes are available. It identifies and removes components of the signal that correlate with the noise.

- Independent Component Analysis (ICA): Highly effective when using a large number of electrodes. It separates statistically independent sources, allowing manual rejection of components identified as cardiac noise.

- Signal Space Projection (SSP): Offers a good balance of noise removal and signal preservation, suitable for larger electrode arrays.

- Canonical Correlation Analysis (CCA): Useful both for noise removal and for directly enhancing task-evoked potentials, sometimes revealing clear signals with single-trial resolution.

- Denoising Source Separation (DSS): An effective method for enhancing task-related signals.

Selection Guide: The choice of algorithm depends on your experimental setup and goals. The table below summarizes the findings from the comparative study.

Essential Materials for a Low-Noise Rig

The following toolkit is essential for implementing the noise reduction strategies discussed above.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

| Item | Function in Noise Reduction |

|---|---|

| Faraday Cage | A conductive enclosure that blocks external electromagnetic interference (EMI) and radio frequency interference (RFI). Must be properly grounded [3] [11]. |

| Specialized Bioamplifier with High CMRR | Amplifies the tiny voltage difference between electrodes while rejecting noise common to both inputs. A Common-Mode Rejection Ratio (CMRR) >100 dB is essential [3]. |

| Shielded, Twisted-Pair Cables | Minimizes inductive and capacitive coupling from power lines and other noise sources into the signal path [3]. |

| Pipette Holder with Sealing O-Rings | Ensures a tight seal for pressure control and prevents mechanical drift. O-rings should be clean and properly greased [12] [15]. |

| Vibratome (e.g., Compresstome) | Produces high-quality acute brain slices with minimal tissue damage and cell death, reducing intrinsic biological noise sources [16]. |

| Carbogen Bubbler (95% O2/5% CO2) | Maintains pH and oxygen levels in ACSF, which is critical for slice health and viability, leading to more stable cells and recordings [12] [16]. |

| HumBug Noise Eliminator | A specialized hardware device that removes 50/60 Hz line noise in real-time without introducing significant phase shifts [11]. |

The table below provides a quick reference for diagnosing common noise types.

Common Noise Types and Signatures

| Noise Signature | Most Likely Source | Corrective Actions |

|---|---|---|

| Strong 50/60 Hz Peaks | Ground loops, poor shielding, unshielded power cables near preparation [3] [11]. | Verify single-point grounding; check Faraday cage; move power supplies [3]. |

| High-Frequency Hash | Radiofrequency interference (RFI) from cell phones, WiFi, or instrumental chatter [3] [8]. | Seal Faraday cage; use a low-pass filter; turn off wireless devices [3] [12]. |

| Slow, Large Baseline Drift | Thermal noise from equipment warm-up, electrode drift, or temperature instability [3] [12]. | Allow amplifier to warm up (30 min); use a digital high-pass filter; stabilize temperature [3]. |

| Intermittent Sharp Spikes | Myogenic (muscle) artifacts, cell phone pings, or poor connections [12] [8]. | Turn off cell phones; check for loose wires; use a commutator for behaving animals [8]. |

| Excessively Large, Wide-Band Noise | Floating ground or reference electrode; amplifier saturation (clipping) [3] [8]. | Check all ground and headstage connections; reduce amplifier gain [3] [8]. |

The following workflow diagram synthesizes the troubleshooting process into a single, actionable pathway.

Troubleshooting Guide: Hardware and Signal Quality

1. My recording has significant 50/60 Hz mains interference (hum). What should I check?

This is typically caused by ground loops or poor shielding.

- Corrective Action: Verify a single-point grounding scheme where all components (amplifier, digitizer, Faraday cage) connect to one common earth ground. Check for continuity in your Faraday cage ground and move power supplies away from the preparation [3]. Also, ensure amplifiers are not set to the same channel, as this can cause issues [17].

2. My signal is noisy with high-frequency "hash." How can I reduce this?

This is often due to Radio Frequency Interference (RFI) or a suboptimal amplifier configuration.

- Corrective Action: Ensure your Faraday cage is fully sealed. Use a low-pass filter on your amplifier or in post-processing, setting the cutoff just above the highest frequency component of your biological signal [3]. Also, use shielded, twisted-pair cables for all signal transmission [3].

3. I am getting a large, drifting baseline. What is the likely cause?

This is usually caused by slow electrode shifts, temperature variations, or amplifier warm-up.

- Corrective Action: Allow your equipment to warm up for at least 30 minutes before recording. Stabilize the temperature control of your recording chamber. You can also apply a digital high-pass filter during analysis to remove the slow drift, but ensure the cutoff is set to avoid distorting your biological signal [3].

4. Why is it important to use high-input impedance amplifiers?

The amplifier's input impedance must be significantly higher than the electrode impedance to prevent "loading" the signal.

- Explanation: A high input impedance (typically in the Gigaohm range) ensures minimal current flow from the recording electrode, allowing the voltage measured to be a faithful representation of the true biological potential [3] [18]. This is critical for maintaining signal fidelity.

5. How does electrode impedance affect my data quality?

High electrode impedance can increase low-frequency noise and reduce the common-mode rejection of your recording system.

- Explanation: While the EEG/ERP signal size isn't reduced [18], higher impedance can make the system more susceptible to environmental noise. This is because random differences in impedance across electrode sites are magnified, degrading the system's ability to reject common noise [18]. The table below summarizes the empirical findings.

Table 1: Impact of Electrode Impedance on Data Quality

| Condition | Effect on Low-Frequency Noise | Impact on Statistical Power (e.g., P3 wave) | Mitigation Strategies |

|---|---|---|---|

| High Electrode Impedance | Increased [18] | Increases number of trials needed for significance [18] | Cool, dry recording environment; High-pass filtering; Artifact rejection [18] |

| Low Electrode Impedance | Reduced [18] | Fewer trials needed for same statistical power [18] | Standard skin cleansing and abrasion [18] |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is the single most important principle for reducing noise in electrophysiology? The most important principle is to maximize the signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) early in the acquisition chain through proper hardware setup. This means prioritizing physical noise reduction (e.g., grounding, shielding) before relying on digital signal processing [3].

Q2: What is a ground loop and how do I avoid it? A ground loop occurs when multiple paths to ground exist, creating a circuit that can pick up mains hum. This is a major source of 60 Hz noise. Avoid it by implementing a single-point grounding scheme, where all equipment is connected to a single, common earth ground point [3]. BIOPAC also recommends using AC-coupled lead adapters in certain multi-amplifier setups to prevent ground loops [17].

Q3: When should I use a notch filter to remove 50/60 Hz noise? A notch filter should be a last resort. It is a very narrow filter that can introduce ringing artifacts into your signal. The preferred method is to eliminate the source of the interference through proper grounding and shielding. If the noise persists, a notch filter can be applied, but with the understanding that any genuine biological signal at that frequency will also be lost [3].

Q4: How does differential amplification work to improve my signal? A differential amplifier improves signal fidelity by measuring the voltage difference between two points: an active electrode and a reference electrode. It subtracts the voltage at the reference from the voltage at the active site. Because environmental noise (like 60 Hz hum) is typically common to both electrodes, this "common-mode" noise is rejected, while the differential biological signal is amplified [3].

Q5: My seal resistance is unstable. What are some common fixes? In patch-clamp experiments, an unstable seal can be caused by several factors. Check that your pressure system is airtight and you can hold positive pressure. Ensure the tiny rubber seals inside your pipette holder are present and in good condition. Also, keep your pipettes free of debris by handling capillary tubes carefully and storing them in a dust-free container [15].

Experimental Protocol: Quantifying the Impact of Electrode Impedance

This protocol is based on the study by [18], which provides a methodology to empirically determine the effects of electrode impedance on data quality.

1. Objective: To determine whether data quality is meaningfully reduced by high electrode impedance under different environmental conditions.

2. Materials:

- EEG recording system with high input impedance.

- Electrode cap with multiple electrodes.

- Abrasive electrolyte gel (e.g., NuPrep) to achieve low impedance.

- Standard conductive gel to achieve high impedance.

- A climate-controlled chamber or room to manipulate temperature and humidity.

3. Methodology:

- Participant & Setup: Record EEG simultaneously from low-impedance and high-impedance electrode sites on the same subject during a task (e.g., an oddball paradigm).

- Impedance Manipulation:

- Low-Impedance Sites: Cleanse and gently abrade the skin at these sites, applying abrasive gel to achieve impedances below 5 kΩ.

- High-Impedance Sites: Cleanse the skin without abrasion, using only conductive gel to achieve impedances above 20 kΩ.

- Environmental Manipulation: Conduct recordings in two different environments:

- Cool/Dry: Standard lab conditions.

- Warm/Humid: Elevated temperature and humidity.

- Data Analysis:

- Calculate the noise level in the raw EEG for both low and high-impedance sites.

- Average the EEG to derive Event-Related Potentials (ERPs).

- For a key component (e.g., P3 or N1 wave), determine the number of trials required to achieve statistical significance for the high-impedance sites compared to the low-impedance sites.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

Table 2: Key Materials for Electrophysiology Experiments

| Item | Function / Explanation |

|---|---|

| Artificial Cerebrospinal Fluid (ACSF) | Mimics the ionic composition of natural CSF to maintain cell health and normal physiology in vitro. Contains salts, pH buffers, and energy sources [19]. |

| Internal/Pipette Solution | Serves as a conductive medium and mimics the cytosol's chemical composition. Its specific ingredients (e.g., K-gluconate, CsCl) can be tailored to control the cell's electrical properties and isolate specific currents [19]. |

| Enzymes for Tissue Slicing (e.g., NMDG, Sucrose, Choline) | During dissection and slicing, sodium chloride in ACSF is often replaced with these substances to reduce neuronal activity and metabolic demand, thereby improving cell survival by preventing excitotoxic damage [19]. |

| Borosilicate Glass Capillaries | Used to fabricate patch or recording micropipettes. The glass is heated and pulled to form a fine tip (1-2 µm) that can form a high-resistance seal (Gigaohm seal) on a cell membrane [19] [15]. |

| Shielded, Twisted-Pair Cables | Used for all low-voltage signal transmission. The twisting and shielding minimize inductive and capacitive coupling between power lines and sensitive signal cables, reducing crosstalk and induced noise [3]. |

| AC-Coupled Lead Adapter (e.g., CBL205) | Used to prevent ground loops when recording EDA/GSR with other biopotential signals (ECG, EEG), allowing for multiple grounds without creating a ground loop [17]. |

Signal Pathway & Troubleshooting Logic

Diagram 1: Noise troubleshooting workflow. This flowchart outlines a systematic approach to diagnosing and resolving noise issues, moving from physical hardware checks to amplifier settings and, finally, to digital processing as a last resort.

Proven Strategies for SNR Enhancement: From Hardware to Post-Processing

Mastering Differential Amplification and Common-Mode Rejection

In electrophysiology research, the ability to detect minuscule biological signals against a background of pervasive electrical interference is fundamental. The precision of these measurements often dictates the quality and validity of scientific conclusions, particularly in critical fields like drug development. Achieving a high signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) is paramount, and this hinges on two core principles: differential amplification and common-mode rejection. This guide provides troubleshooting and foundational knowledge to help researchers master these techniques, ensuring the acquisition of clean, publication-quality data.

# Fundamental Concepts Explained

What is a Differential Amplifier and Why is it Used?

A differential amplifier is a type of electronic amplifier that amplifies the difference between two input voltages while suppressing any voltage common to both inputs [20] [21]. This is crucial in electrophysiology because the tiny biological signals of interest (e.g., action potentials or synaptic currents) are often obscured by much larger environmental noise, such as 50/60 Hz mains interference, which appears equally on both recording electrodes.

What is Common-Mode Rejection Ratio (CMRR)?

The Common-Mode Rejection Ratio (CMRR) is a metric that quantifies a differential amplifier's ability to reject common-mode signals [20]. It is defined as the ratio of the differential gain (Ad) to the common-mode gain (Acm) and is usually expressed in decibels (dB) [20]. A higher CMRR indicates better noise rejection. For high-quality electrophysiology, specialized bioamplifiers typically have CMRR values exceeding 100 dB [3].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Equipment for Low-Noise Electrophysiology

Table 1: Key materials and reagents for high-fidelity electrophysiology recordings.

| Item | Function & Purpose |

|---|---|

| Instrumentation Amplifier | The core component for differential amplification. It provides high input impedance and a high CMRR, making it ideal for measuring small biopotentials [21]. |

| Faraday Cage | A conductive enclosure that surrounds the experimental preparation and headstage to attenuate external electromagnetic interference (EMI) and radio frequency interference (RFI) [3] [22]. |

| Headstage | The first amplification stage, placed extremely close to the signal source (e.g., the animal or dish). It converts the high-impedance signal from the electrode into a low-impedance signal for transmission, minimizing noise pickup [3]. |

| Shielded, Twisted-Pair Cables | Cables used for low-voltage signal transmission. The twisting and shielding minimize inductive and capacitive coupling from power lines and other noise sources [3]. |

| High-Quality Electrodes | Electrodes with low impedance and proper chloriding are essential to minimize junction potential and thermal noise at the interface with the biological preparation [3]. |

# Troubleshooting Common Noise Issues

This section addresses specific noise problems, their likely causes, and corrective actions.

My recording has a persistent 50/60 Hz "hum."

Table 2: Troubleshooting 50/60 Hz power line interference.

| Symptom | Potential Source | Corrective Action |

|---|---|---|

| Sharp 50/60 Hz peak in power spectrum. | Ground loops or poor shielding of the Faraday cage [3]. | Verify and implement a single-point grounding scheme for all equipment [3] [22]. Check for breaks in the Faraday cage grounding. |

| Unshielded power cables near the preparation or signal cables [3]. | Route power cables away from signal cables. Use shielded, twisted-pair cables for all signal paths [3]. | |

| High electrode impedance or impedance mismatch between electrodes [23] [21]. | Use high-quality electrodes with low and matched impedances. Ensure stable electrode connections. |

I am seeing high-frequency "hash" on my signal.

Table 3: Troubleshooting high-frequency noise.

| Symptom | Potential Source | Corrective Action |

|---|---|---|

| High-frequency noise across a wide band. | Radiofrequency interference (RFI) from cell phones, Wi-Fi routers, or other digital equipment [3]. | Ensure the Faraday cage is fully sealed. Use a low-pass filter with a cutoff frequency set just above the fastest component of your biological signal [3]. |

| Instrumental high-frequency chatter. | Apply a digital low-pass filter post-acquisition. |

My signal baseline is drifting slowly.

Table 4: Troubleshooting low-frequency drift.

| Symptom | Potential Source | Corrective Action |

|---|---|---|

| Slow, wandering baseline. | Thermal noise from amplifier warm-up [3]. | Allow the amplifier and other equipment to warm up for at least 30 minutes before starting recordings. |

| Slow shifts in the electrode-electrolyte interface or temperature variations [3]. | Stabilize the temperature control system for the recording chamber. Apply a digital high-pass filter to remove the very slow drift, but ensure the cutoff is set low enough to not distort your biological signal (e.g., synaptic potentials) [3]. |

# Advanced Techniques & Experimental Protocols

Impedance Matching for Superior Common-Mode Rejection

Standard bipolar re-referencing (subtracting one channel from another) often fails to completely remove common-mode noise because the total impedance at each electrode contact is rarely perfectly matched [23]. This mismatch means the same common-mode noise appears at slightly different amplitudes in each channel, preventing perfect cancellation.

Protocol: Impedance Matching Algorithm A software-based solution can estimate and correct for this impedance mismatch [23].

- Record Two Unipolar Channels: Acquire signals from both contacts of a bipolar cuff electrode.

- Estimate Impedance Mismatch: Using a window of data centered on the artifact (e.g., 15 ms for ECG artifacts), calculate the frequency-dependent ratio of the impedances at each contact via spectrotemporal decomposition.

- Apply Correction: Use this ratio to correct the amplitude of one channel.

- Perform Subtraction: Subtract the corrected channel from the other. This method has been shown to suppress persistent ECG interference by an additional 9.2 dB on average compared to simple subtraction [23].

Optimizing Signal-to-Noise Ratio in Short-Duration Recordings

In contexts like intraoperative monitoring, obtaining a reliable signal quickly is essential. The stimulation rate can be optimized to maximize the SNR for a given recording duration.

Protocol: Stimulation Rate Optimization for SEPs A 2023 study systematically varied the rate of stimulus presentation for somatosensory evoked potentials (SEPs) to find the optimum for short recordings [13].

- Stimulation: Record median nerve and tibial nerve SEPs while varying the stimulus repetition rate between 2.7 Hz and 28.7 Hz.

- Data Sampling: Randomly sample a number of sweeps corresponding to recording durations up to 20 seconds.

- SNR Calculation: Calculate the SNR for each condition.

- Result: For short-duration (5 s) median nerve SEP recordings, a stimulation rate of 12.7 Hz achieved the highest SNR. At this high rate, the rapid reduction of noise through averaging outweighs the disadvantage of the slightly smaller amplitude of the evoked response [13]. Note: The optimal rate was different for the tibial nerve (4.7 Hz), indicating this protocol should be empirically validated for different signal types.

Table 5: Quantitative data on stimulation rate optimization for SEPs (median nerve, N20 component, 5s recording).

| Stimulation Rate | Resulting Signal-to-Noise Ratio (SNR) | Physiological Effect |

|---|---|---|

| 4.7 Hz | Lower SNR (p = 1.5e-4) | Larger amplitude, fewer sweeps for averaging. |

| 12.7 Hz | Highest SNR (Median = 22.9) | Amplitude decay and latency increase, but more sweeps for faster noise reduction [13]. |

| 28.7 Hz | Not the optimum | Further amplitude reduction outweighs averaging benefits. |

# Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q: What is the difference between differential mode and common mode?

A: Differential mode refers to the desired signal that appears as a voltage difference between the two input terminals of your amplifier. Common mode represents any unwanted signal or noise that appears simultaneously and in-phase on both input terminals [21].

Q: My amplifier has a high CMRR spec, but I still have noise. Why?

A: CMRR is measured under DC or specific frequency conditions and can degrade at higher frequencies [20]. Furthermore, a high CMRR is ineffective if your electrode impedances are mismatched, as this converts common-mode noise into a differential signal that the amplifier then dutifully amplifies [23] [21]. Always ensure your electrodes and input paths are well-matched.

Q: When should I use a notch filter vs. hardware solutions for 60 Hz noise?

A: Hardware solutions (proper grounding, shielding, and impedance matching) are always the first and best line of defense. A digital notch filter should be a last resort, as it can introduce transient ringing artifacts and will remove any genuine biological signal content that happens to be at exactly 60 Hz [3].

Q: What is the "Driven Right Leg" circuit I've heard about?

A: This is an advanced active noise cancellation technique often used in ECG. It actively drives the patient's body (e.g., via the right leg electrode) with an inverted version of the detected common-mode noise. This feedback loop effectively lowers the common-mode voltage and improves the CMRR of the entire system [22].

Q: How can I manage induction artifacts from magnetic stimulation in my electrophysiology setup?

A: When using electromagnetic coils for magnetic stimulation, voltage can be induced directly in your recording wires. To minimize this:

- Keep recording cables as short as possible and straight—avoid loops [24].

- Use twisted-pair wires to minimize the effective area for magnetic flux [24].

- If possible, orient the coil and cables to minimize the rate of change of magnetic flux through the cable loop (the

dΦ/dtin Faraday's law) [24].

In electrophysiology research, the quality of data is paramount. The quest for a high signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) is often challenged by ubiquitous electromagnetic interference. This guide details the core hardware strategies—grounding, shielding, and Faraday cages—essential for protecting sensitive measurements from noise, thereby ensuring the integrity of your experimental data.

Understanding Signal-to-Noise Ratio (SNR)

Signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) is a measure that compares the level of a desired signal to the level of background noise. It is defined as the ratio of signal power to noise power, often expressed in decibels (dB). A higher SNR indicates a clearer, more detectable signal, which is critical for accurately interpreting electrophysiological data such as spike trains and low-current measurements [25] [1].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. What is the most common source of noise in an electrophysiology rig? The most pervasive source is line power noise (or "mains hum"), which is a periodic interference at the frequency of your local AC power grid (50 Hz or 60 Hz). This noise can originate from the instruments themselves, as well as ambient sources like overhead lighting and motors [11].

2. My setup is inside a Faraday cage, but I still have significant noise. What is the most likely cause? The most probable cause is improper grounding. A Faraday cage must be connected to your potentiostat's or amplifier's ground reference to be effective. Without this connection, a large AC voltage difference can exist between the cage's interior and the instrument's ground, causing noise to capacitively couple into your electrodes [26].

3. What is a "ground loop" and how does it create noise? A ground loop occurs when there are multiple paths between your recording equipment and ground, each with different electrical resistances. This creates differing electrical potentials, causing current to flow through the loops. This unwanted current flow introduces noise into your recordings [11].

4. When is it absolutely necessary to use a Faraday cage? You should always use a Faraday cage when possible, but it becomes crucial for experiments involving low currents (below 1 µA) or high-frequency measurements, such as those in Electrochemical Impedance Spectroscopy (EIS). It is also essential for any experiment requiring very precise and accurate measurements [26].

5. Can I build my own effective Faraday cage? Yes. A simple, effective Faraday cage can be constructed from wood-frame and copper or aluminum mesh, or even a cardboard box wrapped in aluminum foil. The key is to ensure good electrical continuity, especially across seams and door edges [26].

Troubleshooting Guides

Guide 1: Diagnosing and Fixing Ground Loops

Symptoms: A persistent, low-frequency hum (50/60 Hz) in your recording that changes when you disconnect or touch equipment.

Methodology:

- Isolate Components: Power off and disconnect all equipment. Reconnect them one by one while monitoring the signal for the introduction of noise.

- Inspect Grounding: Check if all devices are plugged into the same master power strip to consolidate ground paths.

- Verify Star Ground: Ensure your setup uses a star-grounding system, where each component has a single, dedicated cable connecting it to a central ground point. Avoid "daisy-chaining" grounds from one device to the next [11].

Solution: Implement a star-grounding system. Plug all equipment into a single power strip connected to a dedicated outlet. Establish one central ground point and connect all grounds directly to it.

Guide 2: Optimizing a Faraday Cage

Symptoms: Noise levels remain high despite the cell being inside a Faraday cage.

Methodology:

- Check Cage Grounding: Ensure the Faraday cage is properly grounded. Connect it directly to the ground reference of your potentiostat [26].

- Inspect for Breaks: Look for gaps or breaks in the cage's conductivity, especially at door edges and lids. Use conductive tape or ensure good metal-to-metal contact at these points [26].

- Evaluate Cable Ports: Check all cable feedthroughs. Any holes in the cage should be smaller than 1/10th of the wavelength of the noise you want to block. For general lab noise, keep holes to a few millimeters [26].

Solution: Ground the cage to the instrument, ensure all seams are electrically continuous, and use feedthrough panels with appropriate filters for all cables entering the cage.

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Verifying Faraday Cage and Grounding Efficacy

Objective: To quantitatively demonstrate the noise-reduction benefit of a properly grounded Faraday cage.

Materials:

- Potentiostat

- Electrochemical cell or RC dummy cell

- Faraday cage

- Connecting cables

Procedure:

- Place the electrochemical cell outside the Faraday cage.

- Run a low-current experiment, such as a cyclic voltammetry (CV) scan with a maximum current of around 1 nA.

- Move the cell inside the ungrounded Faraday cage and repeat the measurement.

- Finally, connect the Faraday cage to the ground terminal of your potentiostat and repeat the measurement a third time [26].

Expected Outcome: The results, similar to the referenced data, will show the highest noise outside the cage, reduced but still significant noise inside the ungrounded cage, and the cleanest signal inside the properly grounded cage [26].

Objective: To identify and eliminate individual sources of electromagnetic interference in the laboratory.

Materials:

- Functioning electrophysiology or electrochemistry rig

- Oscilloscope or data acquisition system with real-time display

Procedure:

- Begin with your entire experimental setup powered on and a stable, but noisy, baseline signal.

- One by one, turn off or unplug potential noise sources in the lab: overhead lights, desk lamps, power supplies, stir plates, computers, and monitors.

- Observe the change in the baseline signal on the oscilloscope after disabling each device.

- Once a noise source is identified, you can take steps to permanently remove it, shield it, or power it through a line filter [11].

Data Presentation

Troubleshooting Common Noise Issues

The table below summarizes common noise symptoms, their likely causes, and recommended solutions.

| Symptom | Likely Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Low-frequency hum (50/60 Hz) | Ground loop [11] | Implement a star-grounding system; use a single power strip. |

| High noise with cell in Faraday cage | Ungrounded cage [26] | Connect the Faraday cage directly to the instrument's ground reference. |

| Noise changes when touching equipment | Floating ground or poor grounding [11] | Check and secure all ground connections; ensure potentiostat is properly grounded. |

| High-frequency noise | Gaps in Faraday cage shielding [26] | Ensure all seams and door edges have good electrical contact; reduce hole sizes. |

| Noise in low-current (<1 µA) experiments | Lack of shielding from ambient EM fields [26] | Enclose the experiment within a properly grounded Faraday cage. |

Essential Diagrams

Diagram 1: How a Faraday Cage Shields from External Fields

Diagram 2: Star Grounding vs. Daisy-Chaining

The Scientist's Toolkit

Research Reagent Solutions & Essential Materials

This table details key materials and equipment for implementing effective hardware noise reduction.

| Item | Function | Example/Specification |

|---|---|---|

| Faraday Cage | Enclosure that blocks external electromagnetic fields by redistributing charge on its conductive surface [26] [27]. | Commercial shielded enclosure; or DIY with copper/aluminum mesh [26]. |

| Star Ground Point | A single, central connection point for all grounds in a system to prevent ground loops [11]. | A dedicated grounding bus bar or terminal block. |

| Notch Filter | A filter that attenuates a specific frequency, used to remove 50/60 Hz line noise from the signal [11]. | Built into amplifiers (e.g., A-M Systems) or data acquisition software. |

| HumBug Noise Eliminator | A specialized device that removes line frequency noise in real-time without significant phase shift [11]. | Digitimer HumBug (single or multi-channel). |

| Driven Shield/Guard | Advanced cable shielding technique that actively matches the signal voltage on the shield to prevent current leakage and noise ingress [11]. | Feature in A-M Systems amplifiers. |

| Conductive Tape | Used to seal seams and improve electrical continuity on Faraday cage doors and access panels [26]. | Copper or aluminum foil tape. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. What is the most important electrode property for high-quality neural recordings? The Signal-to-Noise Ratio (SNR) is a gold-standard measure for quantifying the performance of brain recording devices. A high SNR ensures that the meaningful neural signal (such as action potentials or local field potentials) can be clearly distinguished from background noise, which is crucial for accurate data interpretation [5].

2. How do Pt, CNTs, and Au electrodes compare in terms of SNR performance? Research directly comparing these three materials organized in close vicinity (tritrodes) has shown that Pt and CNT electrodes have superior recording performance than Au electrodes across a broad frequency range (5–1500 Hz). This frequency band encompasses both local field potentials (LFP) and multi-unit activity (MUA) [5].

3. Why does electrode impedance matter, and how do these materials affect it? Electrode impedance is inversely proportional to the electrode's active surface area. A lower impedance generally leads to a higher SNR by reducing thermal noise and allowing for more effective cellular stimulation [28]. Nanostructured materials like platinum black (Pt) and carbon nanotubes (CNTs) achieve low impedance by drastically increasing the effective surface area of the electrode compared to smooth gold (Au) [5] [29].

4. We are experiencing poor signal quality in our in vitro neuronal culture recordings. Could the electrode material be the issue? Yes. For cultured neurons, the electrode's surface morphology significantly impacts signal quality. Electrodes with a uniform layer of highly nanoporous platinum have been shown to offer a good trade-off, likely by reducing the distance between neuronal cell bodies and the electrode surface, which results in higher detected signal amplitudes [29]. Ensure your electrodes are designed for biocompatibility and close cell-adhesion.

5. Our team is developing a long-term implantable brain-computer interface (BCI). Which electrode material is more durable? Long-term stability is a critical challenge. A study of electrodes explanted from humans after 956–2130 days of implantation found that, despite showing greater physical degradation, sputtered iridium oxide film (SIROF) electrodes were twice as likely to record neural activity than platinum (Pt) electrodes. This suggests that material choice has a profound impact on long-term functional performance [30].

6. For a flexible, wearable skin device, what electrode characteristics are most critical? For skin-interfaced electrodes, the essential characteristics are a combination of:

- Mechanical Properties: High stretchability, strong adhesion, and excellent conformability to the skin's dynamic surface [31].

- Electrical Characteristics: Low impedance and high SNR for high-quality signal acquisition [31].

- Biocompatibility: The material must be safe for prolonged contact with the skin to avoid irritation or inflammatory responses [31]. Materials like CNTs and Pt can be integrated into soft, flexible composites to meet these requirements.

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: High Electrode Impedance Leading to Noisy Recordings

Possible Causes and Solutions:

Cause 1: Planar, smooth electrode surface with limited surface area.

- Solution: Modify the electrode surface with nanostructures to increase the effective surface area.

- For Au Electrodes: Drop-cast a suspension of multi-walled carbon nanotubes (MWCNTs) onto the gold surface. This has been shown to lower impedance at 1 kHz by approximately 50% compared to bare gold electrodes [28].

- For Pt Electrodes: Electrochemically deposit nanoporous platinum (platinum black) to create a highly porous, high-surface-area coating [29].

- Solution: Modify the electrode surface with nanostructures to increase the effective surface area.

Cause 2: Poor adhesion between a nanostructured coating (like CNTs) and the underlying metal electrode.

- Solution: For CNT-modified Au electrodes, pre-treat the gold substrate with a surface roughening process. This enhances mechanical interlocking, preventing CNT detachment in biological solutions and ensuring long-term stability [28].

Problem: Unstable Recordings or Signal Loss in Chronic Implants

Possible Causes and Solutions:

- Cause: Physical degradation of the electrode material over time.

- Solution: Choose robust materials and designs. Quantitative studies of explanted human electrodes show that material degradation correlates with functional decline. While SIROF can degrade, it may still maintain function. Investigate materials with a strong combination of electrochemical stability and mechanical resilience for long-term implants [30].

Problem: Poor Cell Adhesion or Biocompatibility on Electrodes

Possible Causes and Solutions:

- Cause: Cytotoxic materials or sharp, irregular surface morphologies that impede cell growth.

- Solution:

- Utilize highly nanoporous platinum deposited via chronoamperometry at -0.4 V, which produces uniform layers with minimal "edge effects" that can break off and cause cytotoxicity [29].

- CNTs have also been shown to provide an excellent support for nerve cell adhesion and growth, forming tight interfaces with cells that can improve signal quality [28].

- Solution:

Quantitative Performance Data

The following table summarizes key performance metrics for Pt, CNT, and Au electrodes based on the cited research:

Table 1: Electrode Material Performance Comparison

| Metric | Platinum Black (Pt) | Carbon Nanotubes (CNTs) | Gold (Au) | Notes & Context |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SNR Performance | Superior [5] | Superior [5] | Inferior [5] | Comparison in tritrodes recording cortical slow oscillations. |

| Impedance | Very Low [29] | Very Low [28] | Higher [5] | Low impedance is a key factor in achieving high SNR. |

| Key Advantage | High surface area from nanoporosity; established deposition methods [29]. | High conductivity & surface area; excellent cell-adhesion properties [28]. | High biocompatibility & conductivity for plain metals [31]. | |

| Noted Challenge | Can have heterogeneous deposits with cytotoxic edge effects if not fabricated properly [29]. | Requires stable adhesion to substrate; long-term toxicity concerns require investigation [32] [28]. | Higher impedance limits SNR performance compared to nanostructured materials [5]. |

Table 2: Long-Term Clinical BCI Performance (Explanted Electrodes)

| Metric | Sputtered Iridium Oxide (SIROF) | Platinum (Pt) | Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Likelihood to Record | Twice as likely to record neural activity [30] | Standard | After 956-2130 days implantation in human cortex. |

| Physical Degradation | Greater physical degradation observed [30] | Less physical degradation [30] | SIROF's functional superiority persists despite more physical damage. |

| Impedance Correlation | 1 kHz impedance significantly correlated with damage and performance [30] | Information Not Specific | Makes SIROF impedance a potential reliable indicator of in vivo degradation. |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Fabrication of Nanoporous Platinum Microelectrodes

This protocol is adapted from methods used to create uniform, biocompatible platinum black coatings for neuroscience applications [29].

- Objective: To electrodeposit a uniform layer of nanoporous platinum on platinum microelectrodes to lower impedance and improve SNR.

- Materials:

- Fabricated Pt microelectrode arrays.

- Chloroplatinic acid solution (e.g., 10 mM Hexachloroplatinic acid in water).

- Formic acid (optional additive) or lead-free plating solution.

- Potentiostat.

- Standard three-electrode electrochemical cell (working electrode = Pt MEA, counter electrode = Pt wire, reference electrode = Ag/AgCl).

- Method:

- Clean the Pt microelectrode array thoroughly.

- Place the electrode in the electroplating solution.

- Apply a constant potential of -0.4 V (vs. Ag/AgCl) using chronoamperometry for a defined period (e.g., 50-200 seconds). Note: Constant potential deposition is recommended over constant current for achieving uniform layers with minimal edge effects [29].

- Rinse the electrode gently with deionized water to remove any residual plating solution.

- Validation: Characterize the deposited layer using Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM) to confirm a uniform, nanoporous morphology. Perform Electrochemical Impedance Spectroscopy (EIS) to verify a significant reduction in impedance, typically at 1 kHz [29].

Protocol 2: Drop-Casting CNTs onto Gold MEAs for Neural Interfaces

This protocol describes a facile method to create stable CNT-modified gold electrodes with low impedance [28].

- Objective: To adhere a stable layer of carbon nanotubes to gold MEAs to reduce impedance and enhance neural interfacing.

- Materials:

- Fabricated Au microelectrode arrays on a glass substrate.

- Multi-walled carbon nanotubes with hydroxyl functional groups (MWCNT-OH).

- Deionized (DI) water.

- Ultrasonic bath.

- Parafilm.

- Method:

- Prepare a highly dispersed suspension of MWCNT-OH in DI water at a concentration of 1 mg/mL by sonicating for 30 minutes.

- Use Parafilm to create a well (e.g., a 1x1 cm² window) around the active electrode area on the MEA.

- Drop-cast 20 μL of the CNT suspension into the exposed window.

- Allow the electrode to dry at ambient temperature for 30 minutes. The nanotubes will adhere to the roughened gold surface.

- Remove the Parafilm. The resulting CNT-modified-Au MEA is now ready for use [28].

- Validation: Perform EIS to measure the impedance. This modification has been shown to reduce impedance at 1 kHz by 50% compared to bare Au electrodes (e.g., from ~17 kΩ to ~8 kΩ) [28].

Signaling Pathways and Experimental Workflows

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

Table 3: Key Reagents and Materials for Electrode Fabrication and Evaluation

| Item | Function/Brief Explanation | Example Context |

|---|---|---|

| Chloroplatinic Acid | Source of platinum ions for the electrochemical deposition of platinum black (nanoporous Pt) [29]. | Fabrication of nanoporous Pt microelectrodes. |

| Multi-Walled Carbon Nanotubes (MWCNTs) | Nanomaterial used to coat electrodes, providing a high surface area for low impedance and excellent cell-adhesion properties [28]. | Drop-casting on Au MEAs to create CNT-modified electrodes. |

| PBASE (1-pyrenebutyric acid N-hydroxysuccinimide ester) | A linker molecule used for the stable functionalization of CNT surfaces, enabling efficient attachment of biomolecules [33]. | Functionalizing CNT-FET biosensors for specific biomarker detection. |

| Potentiostat | An electronic instrument required for controlling electrochemical reactions during processes like electrodeposition and for performing Electrochemical Impedance Spectroscopy (EIS) [29]. | Electrodeposition of Pt; EIS characterization of electrodes. |

| Sputter Coater | A device used to deposit thin, uniform layers of metals (like Gold or Platinum) onto substrates in a vacuum environment [28]. | Fabrication of the initial conductive metal layer on MEAs. |

| PEDOT:PSS | A conductive polymer hydrogel that can be used as a coating to lower contact impedance and improve signal quality in soft electronics [31]. | Creating soft, conformable electrodes for wearable skin devices. |

Troubleshooting Guides

Troubleshooting Guide 1: Common Artifacts in Electrophysiological Recordings

Problem: Baseline Wander

- Symptoms: A slow, rolling drift of the signal baseline obscuring low-frequency components.

- Common Causes: Patient breathing, poor electrode contact, or perspiration [34].

- Solution:

- Ensure proper skin preparation and secure electrode attachment.

- Apply a high-pass filter with a cutoff frequency of 0.5 Hz or lower to remove the slow drift [34].

- Use a zero-phase delay (ZPD) high-pass filter to prevent distortion of the ST segment in ECG signals, which can lead to false-positive diagnoses of ischemia [34].

Problem: High-Frequency Muscle or Environmental Noise

- Symptoms: A fuzzy, erratic signal superimposed on the clean waveform.

- Common Causes: Patient movement (tremors, shivering), fluorescent lights, or nearby Bluetooth/cell phone devices [34].

- Solution:

- Use a low-pass filter with a cutoff frequency typically set at 150 Hz, as most clinically relevant ECG information falls below this threshold [34].

- If noise persists, lower the cutoff frequency (e.g., to 100 Hz), but be aware that this will increasingly distort signal amplitude, potentially affecting diagnoses based on QRS amplitude [34].

- For persistent 50/60 Hz power line noise, enable the power-line filter, which is a nonlinear filter designed to remove this specific interference without distorting the rest of the signal [34].

Problem: Low Signal-to-Noise Ratio (SNR) for Evoked Potentials

- Symptoms: The signal of interest (e.g., a sensory evoked potential) is buried in noise, making single-trial analysis impossible.

- Common Causes: Small amplitude of the neural signal relative to background physiological (e.g., cardiac, muscular) and instrumental noise [14].

- Solution:

- Averaging: The traditional method involves averaging hundreds to thousands of time-locked trials to improve the SNR [14].

- Spatial Filtering with Multiple Electrodes: When using multi-electrode arrays, employ advanced algorithms like Independent Component Analysis (ICA) or Principal Component Analysis (PCA) to separate the neural signal from spatially correlated noise like cardiac artifacts [14].

Troubleshooting Guide 2: Artifacts Introduced by Signal Processing

Problem: Signal Distortion After Filtering

- Symptoms: Ringing (oscillations) near sharp waveforms, smearing of rapid onset transients, or changes in waveform amplitude.

- Common Causes: Overly aggressive filtering, incorrect filter type selection, or phase distortion [34] [35].

- Solution:

- Use filters with a gradual roll-off (wider transition bandwidth) to minimize ringing in the time domain [35].

- Prefer zero-phase or linear-phase Finite Impulse Response (FIR) filters to avoid phase distortion that can alter the temporal relationship between signal components [34] [36].

- Always use the minimal necessary filtering and inspect the raw, unfiltered signal first [34].

Problem: Poor Performance of Deconvolution

- Symptoms: The deconvolved signal is noisy, amplified, or contains unrealistic artifacts.

- Common Causes: Attempting to recover frequency components that were obliterated by the original convolution or are below the noise floor of the system [37].

- Solution:

- Limit Your Greed: Design a less aggressive deconvolution filter. Do not try to make the desired output pulse excessively narrow [37].

- Place Gain Limits: Prevent the deconvolution filter from applying extremely high gain at frequencies where the original signal-to-noise ratio is very poor [37].

- This is an iterative process; test the deconvolution at different performance levels and validate the results against known benchmarks [37].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: When should I use a filter versus signal averaging to improve my signal?

A: The choice depends on your signal characteristics and experimental goals.

- Use Filtering when the frequency content of your noise does not overlap with your signal, or when you need to analyze single-trial or continuous data (e.g., real-time monitoring, arrhythmia detection) [34].

- Use Averaging when your signal is time-locked to a repetitive event (e.g., sensory evoked potentials) and the noise is random. Averaging improves SNR by the square root of the number of trials but obscures trial-to-trial variability [14].

Q2: What is the fundamental difference between filtering and deconvolution?

A: Both are used to improve signals, but they address different problems.

- Filtering selectively attenuates certain frequency components (e.g., high-frequency noise or low-frequency drift). It is often used to remove noise that is additive to the signal [34] [35].

- Deconvolution aims to reverse a convolution process. It attempts to compensate for an undesired smoothing or distortion that the signal underwent (e.g., due to detector response or a specific transmission channel) to recover the original, pre-distorted signal [37].

Q3: My deconvolution attempt failed and amplified the noise. Why?

A: This is a common limitation. Deconvolution requires amplifying frequencies that were attenuated by the original convolution. If these frequencies contain noise rather than the original signal, the noise will be amplified along with the signal. This is particularly problematic if the convolution function (e.g., impulse response) has frequencies where its value is zero or very small, as the deconvolution filter would require infinite or very high gain at those frequencies [37] [38]. Successful deconvolution requires a well-understood convolution process and a sufficiently high signal-to-noise ratio in the original recorded signal [37].

Q4: For a high-pass FIR filter, what is a recommended transition bandwidth?

A: A good starting heuristic is to set the transition bandwidth to [35]:

- Twice the cutoff frequency for cutoffs ≤ 1 Hz.

- 2 Hz for cutoff frequencies between 1 Hz and 8 Hz.

- 25% of the cutoff frequency for cutoffs > 8 Hz. It is recommended to use as wide a transition band as possible, as steeper slopes increase distortion in the time domain [35].

Protocol 1: Removal of Cardiac Artefact from Electrospinography (ESG) Data

Objective: To remove the large cardiac artefact from non-invasive spinal cord recordings to enable analysis of small-amplitude Somatosensory Evoked Potentials (SEPs) without extensive averaging [14].

Methodology:

- Data Acquisition: Simultaneously record ESG using a multi-electrode patch on the neck/back and ECG from a participant receiving transcutaneous electrical stimulation of the median or tibial nerve [14].

- Algorithm Selection: Choose a denoising algorithm based on your electrode array size.

- Implementation:

- Validation: Compare the amplitude of the cardiac artefact before and after processing. Assess the clarity and amplitude of the SEP (e.g., the N13 component for cervical recordings) in the processed data.

Protocol 2: Real-Time Signal Processing in the Electrophysiology Lab

Objective: To enable real-time, intraprocedural analysis of electrogram (EGM) signals during cardiac ablation procedures to provide mechanistic insights into arrhythmias [39].

Methodology: