Mapping the Mind: Neural Circuitry in Depression and the Mechanisms of Antidepressant Response

This article synthesizes contemporary research on the neural circuit dysfunctions underlying Major Depressive Disorder (MDD) and the mechanisms through which treatments confer their effects.

Mapping the Mind: Neural Circuitry in Depression and the Mechanisms of Antidepressant Response

Abstract

This article synthesizes contemporary research on the neural circuit dysfunctions underlying Major Depressive Disorder (MDD) and the mechanisms through which treatments confer their effects. Aimed at researchers and drug development professionals, it explores the transition from a monoamine-centric view to a circuit-based taxonomy of depression. The content details the application of advanced techniques like optogenetics and chemogenetics for dissecting circuit-specific pathologies, analyzes the limitations of current monoaminergic treatments, and evaluates novel, rapid-acting glutamatergic agents and neuromodulation therapies. By integrating foundational exploration with methodological applications, troubleshooting, and comparative validation, this review provides a comprehensive framework for developing next-generation, circuit-targeted antidepressant strategies.

The Stressed Brain: Defining the Neural Circuit Pathology of Major Depressive Disorder

The pathophysiological understanding of major depressive disorder (MDD) has evolved substantially from initial monoamine-based hypotheses toward sophisticated circuit-level models that integrate neuroimaging, molecular biology, and computational approaches. This whitepaper examines this evolution, highlighting how deficiencies in monoamine neurotransmitters—serotonin (5-HT), norepinephrine (NE), and dopamine (DA)—map onto distinct neural circuits and clinical manifestations of MDD. We synthesize current evidence linking monoaminergic systems to large-scale brain networks involved in reward processing, emotion regulation, and executive function. Advanced neuroimaging techniques and personalized computational modeling now enable researchers to predict treatment response and identify novel therapeutic targets within defined neural circuits. This paradigm shift from chemical imbalance to circuit dysfunction provides a more comprehensive framework for developing targeted, effective interventions for this heterogeneous disorder.

Major depressive disorder (MDD) represents a significant global health challenge, affecting over 350 million people worldwide and ranking as a leading cause of disability [1]. The economic burden is substantial, with depression-associated costs estimated at $83 billion annually in the United States alone [1]. Traditionally, depression has been characterized by persistent sad mood, anhedonia (loss of pleasure), changes in appetite and sleep, fatigue, and cognitive impairments [2]. The heterogeneity of these clinical manifestations suggests diverse underlying pathophysiological mechanisms that have been the focus of intensive research.

The evolution of depression models has followed a trajectory from neurotransmitter-based theories to circuit-level explanations:

- 1960s-1990s: Dominance of monoamine hypothesis focusing on synaptic neurotransmitter deficiencies

- 2000-2010s: Integration of neuroendocrine, neuroplasticity, and inflammation hypotheses

- 2010-present: Emergence of circuit-based models integrating neuroimaging, genetics, and computational approaches

This whitepaper examines this evolutionary trajectory, emphasizing how modern research frameworks reconcile monoaminergic mechanisms with circuit-level dysfunction to advance both understanding and treatment of MDD.

Historical Foundation: The Monoamine Hypothesis

Core Monoamine Deficits in MDD

The monoamine hypothesis, originating in the 1960s, proposed that MDD results from deficiencies in key neurotransmitters: serotonin (5-HT), norepinephrine (NE), and dopamine (DA) [3] [2]. This hypothesis gained support from the observed therapeutic effects of early antidepressants that increased synaptic concentrations of these monoamines. While this model has been refined over decades, it continues to inform treatment development and understanding of depression pathophysiology.

Table 1: Monoamine Systems and Their Roles in Depression Pathophysiology

| Monoamine | Primary Brain Regions | Proposed Role in MDD | Therapeutic Target |

|---|---|---|---|

| Serotonin (5-HT) | Raphe nuclei, widespread cortical projections | Mood regulation, sleep, appetite, cognitive functions [3] | SSRIs, SNRIs, atypical antidepressants |

| Norepinephrine (NE) | Locus coeruleus, limbic system, prefrontal cortex | Arousal, attention, stress response, emotional memory [3] | SNRIs, TCAs, NDRIs |

| Dopamine (DA) | Ventral tegmental area, nucleus accumbens, prefrontal cortex | Reward, motivation, pleasure, executive function [3] | Bupropion, atypical antipsychotics |

The Three Primary Color Model of Basic Emotions

Recent refinements to the monoamine hypothesis propose distinct emotional domains for each neurotransmitter system. The "Three Primary Color Model" suggests that DA mediates joy/reward, NE mediates fear/anger, and 5-HT mediates disgust/sadness [3]. This model provides a framework for understanding how monoamine systems work in concert to generate diverse emotional states, with imbalances leading to specific depressive symptomatology.

Limitations and Evolution of Monoamine Theories

Clinical Challenges to the Monoamine Hypothesis

Despite its historical influence, several clinical observations challenge the simplicity of the monoamine hypothesis:

- Treatment Resistance: Approximately 30% of MDD patients do not respond adequately to conventional monoamine-targeting antidepressants [2].

- Delayed Onset: While pharmacological effects on monoamines occur within hours, clinical improvement typically requires weeks of treatment [3].

- Incomplete Efficacy: Even among responders, many patients experience residual symptoms despite adequate monoaminergic modulation [1].

These limitations prompted investigation into additional pathophysiological mechanisms, including hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis dysregulation, neuroinflammation, and impaired neuroplasticity [2].

Expanding Pathophysiological Models

Modern understanding recognizes multiple interacting systems in MDD pathogenesis:

Table 2: Evolving Pathophysiological Models of Depression

| Model | Key Mechanisms | Supporting Evidence | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Monoamine Hypothesis | Deficiencies in 5-HT, NE, and DA signaling [3] | Antidepressant efficacy; neurochemical studies | Incomplete explanation of treatment resistance |

| HPA Axis Dysregulation | Chronic stress, cortisol excess, glucocorticoid receptor resistance [2] | Hypercortisolemia in MDD; CRF abnormalities | Not specific to MDD; inconsistent across patients |

| Neuroinflammation | Elevated pro-inflammatory cytokines; microglial activation [2] | Increased CRP, IL-6 in MDD; sickness behavior | Causal relationships not fully established |

| Neuroplasticity Model | Reduced BDNF, impaired neurogenesis, synaptic dysfunction [2] | Post-mortem brain studies; animal models | Temporal relationship with depression onset unclear |

| Circuit Dysfunction | Large-scale network disruption; functional connectivity changes [4] | fMRI studies; network-based computational models | Heterogeneity in circuit abnormalities |

The Circuit-Level Paradigm: Integrating Monoamines with Neural Networks

Key Circuits in Depression Pathophysiology

Modern neuroimaging research has identified several large-scale brain networks consistently implicated in MDD:

- Reward Circuit: Includes ventral striatum, ventral pallidum, orbitofrontal cortex (OFC), anterior cingulate cortex (ACC), and thalamus [4]. Dysfunction in this circuit underlies anhedonia and amotivation, core features of MDD.

- Emotion Regulation Circuit: Involves prefrontal cortex, hippocampus, amygdala, OFC, and ACC [4]. This circuit modulates emotional responses, with dysfunction leading to persistent negative affect.

- Cognitive Control Network: Encompasses dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (DLPFC) and associated regions. Impairment contributes to executive dysfunction in MDD.

Monoamine-Circuit Interactions

The circuit-level paradigm does not discard monoamine theories but rather incorporates them into a more comprehensive model. Monoaminergic systems modulate information processing within these circuits:

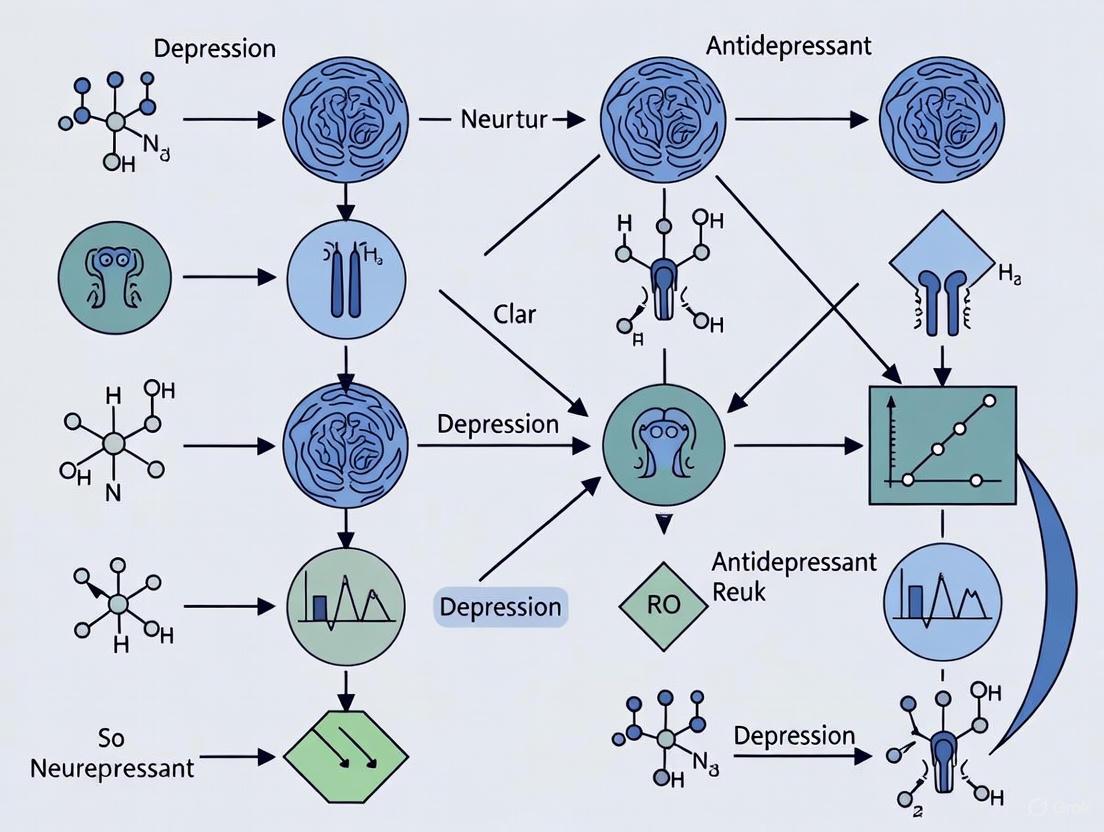

Monoamine-Circuit Interactions in MDD Pathophysiology

This diagram illustrates how primary monoamine systems modulate specific neural circuits that give rise to core clinical manifestations of MDD, while also demonstrating the cross-system interactions that contribute to the disorder's complexity.

Glial Cell Contributions to Circuit Dysfunction

Recent research has highlighted the crucial role of glial cells, particularly astrocytes, in modulating circuit function in MDD. Postmortem studies of MDD patients show reduced densities of glial cells in prefrontal cortex, hippocampus, and amygdala [2]. Astrocytic dysfunction affects multiple pathways relevant to depression:

- Glutamate Homeostasis: Reduced expression of glutamate transporter-1 (GLT-1) and glutamine synthase in astrocytes impairs glutamate clearance, potentially contributing to excitotoxicity [2].

- Purinergic Signaling: Activation of purinergic ligand-gated ion channel 7 receptors (P2X7R) in astrocytes under chronic stress contributes to depressive-like behaviors in animal models [2].

- Blood-Brain Barrier Function: Altered aquaporin-4 (AQP4) expression in astrocytic endfeet may affect neurovascular coupling in MDD [2].

Methodological Approaches for Circuit-Level Analysis

Neuroimaging Biomarkers and Predictive Modeling

Advanced neuroimaging techniques enable researchers to identify circuit-based biomarkers of treatment response. Recent studies using hierarchical local-global imaging and clinical feature fusion graph neural network models have achieved 76.21% accuracy in predicting remission following SSRI treatment [4]. Key contributing brain regions include:

- Right globus pallidus and bilateral putamen (reward processing)

- Left hippocampus (memory and contextual processing)

- Bilateral thalamus (sensory integration)

- Bilateral anterior cingulate gyrus (emotion regulation)

Table 3: Experimental Protocols for Circuit-Level Depression Research

| Methodology | Key Applications in Depression Research | Technical Considerations | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Resting-state fMRI | Functional connectivity mapping; network identification | Sensitivity to motion artifacts; analytical pipeline variability | [4] |

| Graph Neural Networks (GNNs) | Predictive modeling of treatment response; network analysis | Requires large datasets; computational intensity | [4] |

| Personalized Brain Modeling | Individualized treatment prediction; circuit targeting | Integration of multiple data types; validation challenges | [5] |

| Electroencephalography (EEG) | Measuring slow-wave activity; treatment response biomarkers | Limited spatial resolution; signal processing complexity | [5] |

Protocol: Local-Global Graph Neural Network for Predicting Antidepressant Response

This protocol outlines the methodology for implementing a hierarchical local-global imaging and clinical feature fusion graph neural network (LGCIF-GNN) to predict antidepressant treatment outcomes [4]:

Participant Selection and Clinical Assessment

- Recruit medication-free MDD patients (sample size: ~279)

- Collect demographic data (age, sex, education)

- Administer clinical assessments: Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HAMD), Quality of Life Enjoyness and Satisfaction Questionnaire (QLES)

Neuroimaging Data Acquisition

- Acquire resting-state fMRI using standard parameters (TR/TE: 2000/30ms, voxel size: 3×3×3mm)

- Collect high-resolution structural images (MPRAGE sequence)

Data Preprocessing

- Implement standard fMRI preprocessing pipeline: slice timing correction, motion realignment, normalization to MNI space, smoothing

- Extract time series from predefined regions of interest (ROIs)

Feature Extraction and Graph Construction

- Compute dynamic functional connectivity using sliding window approach

- Construct subject-level graphs with ROIs as nodes and functional connectivity as edges

- Create population-level graph based on functional and clinical similarity between subjects

Model Architecture and Training

- Implement local GNN to capture intra-subject ROI-level dynamics using bidirectional GRU encoder

- Implement global GNN to model inter-subject relationships

- Fuse imaging and clinical features in final layers

- Train model using cross-validation with remission status as outcome

Model Validation

- Evaluate performance on internal validation dataset

- Test generalizability on external independent dataset

- Assess key predictive brain regions through feature importance analysis

Computational Workflow for Predicting Antidepressant Response

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 4: Essential Research Tools for Circuit-Level Depression Investigations

| Category | Specific Reagents/Tools | Research Applications | Key Functions |

|---|---|---|---|

| Neuroimaging Biomarkers | Resting-state fMRI; Structural MRI; DTI | Circuit identification; connectivity analysis | Maps structural and functional neural networks [4] |

| Computational Modeling | Graph Neural Networks (GNNs); Personalized brain modeling | Treatment prediction; dose optimization | Integrates multimodal data for individual predictions [4] [5] |

| Molecular Assays | PCR; Western Blot; Immunohistochemistry | Gene expression; protein quantification | Measures molecular correlates of circuit dysfunction [2] |

| Electrophysiology Tools | EEG; Slow-wave measurement | Brain dynamics; treatment response biomarkers | Quantifies brain activity patterns relevant to depression [5] |

| Genetic Analysis | GWAS; Transcriptomic profiling | Risk variant identification; pathway analysis | Identifies genetic factors in circuit vulnerability [2] |

Therapeutic Implications and Future Directions

Circuit-Targeted Interventions

The circuit-based model of depression has stimulated development of novel therapeutic approaches:

- Neuromodulation Techniques: Transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS) and deep brain stimulation (DBS) target specific nodes within dysfunctional circuits.

- Anesthetic Manipulation: Propofol and ketamine are investigated for their ability to modulate slow-wave activity and produce rapid antidepressant effects [5].

- Personalized Dosing: Computational models optimize drug dosing based on individual brain dynamics to achieve therapeutic "sweet spots" [5].

Integrated Pathophysiological Model

The evolving understanding of MDD pathophysiology integrates multiple levels of analysis:

Integrated Pathophysiological Model of MDD

The pathophysiological understanding of depression has evolved substantially from simplistic monoamine theories toward integrated circuit-based models. This paradigm shift acknowledges the complex interactions between genetic vulnerability, environmental stressors, molecular mechanisms, and large-scale neural network dysfunction. Modern research approaches that combine advanced neuroimaging, computational modeling, and molecular biology provide unprecedented opportunities to decode depression heterogeneity and develop targeted, effective interventions.

The future of depression research lies in personalized medicine approaches that account for individual variability in circuit organization and function. By identifying specific circuit-based biomarkers and developing interventions that normalize dysfunctional network activity, researchers can move beyond the limitations of conventional monoamine-targeting treatments. This evolving framework not only enhances our understanding of depression pathophysiology but also promises more effective, precisely targeted therapeutic strategies for this debilitating disorder.

Chronic Stress as a Key Instigator of Maladaptive Neural Circuit Rewiring

Chronic stress is a significant precipitant of maladaptive neural plasticity, disrupting the intricate balance of limbic and cortical circuits to foster vulnerability to psychiatric disorders such as major depressive disorder (MDD). This whitepaper delineates the mechanisms through which repeated stress exposure instigates pathophysiological rewiring within key brain networks, including the amygdala, prefrontal cortex (PFC), hippocampus, and reward circuits. We synthesize evidence of stress-induced alterations at molecular, cellular, and systems levels, highlighting the opposing patterns of plasticity in nodes of the limbic system. Furthermore, we explore the implications of these neural circuit changes for the heterogeneity of antidepressant treatment response. The insights provided herein aim to inform the development of targeted, circuit-based therapeutics for stress-related psychopathologies.

The physiological response to stress, encompassing neuroendocrine, autonomic, and behavioral changes, is fundamentally adaptive, promoting survival in the face of acute threats [6]. However, chronic activation of stress response systems leads to a cumulative burden, or "allostatic load," which has deleterious effects on health, including increased risk for hypertension, metabolic syndrome, and neuropsychiatric illnesses [6]. The brain is a primary target of stress mediators, and persistent exposure to glucocorticoids (cortisol in primates, corticosterone in rodents) and other stress-signaling molecules can trigger maladaptive plasticity within emotionally salient neural circuits [6] [7].

A critical insight from recent research is that chronic stress does not uniformly weaken the brain; rather, it pathologically rewires specific circuits, leading to contrasting patterns of plasticity in different regions. Convergent evidence indicates that prolonged stress leads to overall neuronal atrophy and synaptic depression in the PFC and hippocampus, while regions such as the amygdala and nucleus accumbens (NAc) exhibit changes consistent with neuronal hypertrophy and synaptic potentiation [7]. This maladaptive reorganization underlies core symptoms of depression, including negative affect, anhedonia, and cognitive deficits. This whitepaper examines the mechanisms of this stress-induced circuit rewiring within the context of depression research and its implications for predicting and improving antidepressant response.

Maladaptive Rewiring of Key Neural Circuits by Chronic Stress

Chronic stress disrupts the delicate equilibrium between key brain regions responsible for emotional regulation, reward processing, and cognition. The following sections detail the pathophysiological changes in specific circuits.

Limbic Forebrain Networks: A Central Hub for Stress Integration

Emotional stressors are distinguished by their capacity to induce long-term alterations in limbic forebrain networks, which are associated with the cognitive and affective symptoms in stress-related disorders [6]. The hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis, the canonical stress response system, is heavily regulated by these forebrain regions. Chronic stress and conditions like MDD are linked to diminished sensitivity to glucocorticoids in the limbic forebrain, which impairs negative feedback regulation of the HPA axis and disrupts the capacity for adaptive cognitive and affective adjustments [6].

Table 1: Contrasting Effects of Chronic Stress on Key Brain Regions

| Brain Region | Effect of Chronic Stress | Functional Consequence | Molecular Correlates |

|---|---|---|---|

| Prefrontal Cortex (PFC) | Neuronal atrophy, dendritic spine loss, synaptic depression [7] | Impaired executive function, cognitive inflexibility | Deficits in BDNF, disrupted mTOR signaling [7] |

| Hippocampus | Neuronal atrophy, suppressed neurogenesis, synaptic deficits [7] | Impaired context memory, dysregulated HPA feedback | Reduced BDNF, increased glucocorticoid signaling [6] [7] |

| Amygdala (Basolateral & Central) | Neuronal hypertrophy, dendritic arborization, synaptic potentiation [7] | Hyper-anxiety, heightened fear response | Increased BDNF and CRF signaling [7] |

| Nucleus Accumbens (NAc) | Synaptic potentiation [7] | Anhedonia, reduced motivation | Increased BDNF and CRF signaling [7] |

Molecular Signaling Pathways in Stress-Induced Plasticity

The structural and functional rewiring of neural circuits is driven by alterations in key molecular signaling pathways.

- Brain-Derived Neurotrophic Factor (BDNF): BDNF plays a region-specific role in stress pathology. Chronic stress decreases BDNF levels in the hippocampus and PFC, contributing to neuronal atrophy. In contrast, stress increases BDNF in the NAc and amygdala, promoting maladaptive synaptic strengthening. This opposing regulation is a core mechanism for the divergent plasticity observed across circuits [7].

- Glutamatergic Signaling & mTOR Pathway: The rapid-acting antidepressant ketamine, an NMDA receptor antagonist, has illuminated the role of glutamate and downstream signaling. Ketamine blockade of NMDA receptors leads to a burst of glutamate release and subsequent activation of AMPA receptors. This triggers signaling cascades that activate the mTOR pathway, a critical regulator of protein synthesis, leading to rapid synaptogenesis in stress-atrophied regions like the PFC and hippocampus [7]. Chronic stress is believed to suppress this pathway, and its restoration is a promising therapeutic avenue.

- Calcium/Calmodulin-Dependent Protein Kinase II (CaMKII): In the lateral habenula (LHb), a nucleus hyperactive in depression, stress upregulates βCaMKII. This increases membrane insertion of GluR1-containing AMPA receptors, enhancing excitatory drive and contributing to depressive phenotypes [7].

The diagram below illustrates the core signaling pathway implicated in stress-induced synaptic deficits and the proposed mechanism of rapid-acting antidepressants like ketamine.

Experimental Protocols for Investigating Circuit Rewiring

To establish causal and mechanistic evidence for stress-induced rewiring, researchers employ a suite of sophisticated techniques. The following protocol exemplifies a comprehensive approach.

Integrated Protocol: Assessing Social Defeat Stress-Induced Rewiring of Reward Circuits

This protocol is widely used to study anhedonia and depression-like behaviors in rodents [7].

1. Stress Induction (Chronic Social Defeat Stress):

- Animals: Adult male C57BL/6J mice are used as intruders; larger, aggressive CD-1 mice are used as residents.

- Procedure: Each C57BL/6J mouse is placed in the home cage of a novel, aggressive CD-1 mouse for 5-10 minutes, resulting in physical confrontation. After the confrontation, the animals are housed in divided cages with sensory contact for the remainder of the 24-hour period. This cycle is repeated for 10 consecutive days with a novel CD-1 mouse each day.

- Control: Control mice are housed in pairs but are not exposed to aggressive conspecifics.

2. Behavioral Phenotyping (Post-Stress):

- Sucrose Preference Test: Measures anhedonia. Mice are presented with two bottles, one with sucrose solution and one with water. A significant reduction in sucrose preference compared to controls indicates anhedonia.

- Social Interaction Test: Measures social avoidance. The mouse is placed in an arena with a novel CD-1 mouse enclosed in a wire cage. Time spent in the "interaction zone" around the cage is measured. Defeated mice typically show reduced interaction.

- Forced Swim Test: Measures behavioral despair. The mouse is placed in a inescapable cylinder of water for 6 minutes. Increased immobility time is interpreted as a depressive-like phenotype.

3. Neural Circuit Analysis:

- Viral Vector-Mediated Circuit Mapping: Inject a Cre-dependent AAV encoding a fluorescent reporter (e.g., GFP) into the VTA of dopamine transporter (DAT)-Cre mice. This labels VTA dopamine neurons and their projections to the NAc.

- Ex Vivo Electrophysiology: Prepare brain slices containing the NAc. Record excitatory postsynaptic currents (EPSCs) from medium spiny neurons (MSNs) while optically stimulating VTA dopamine terminals. This assesses the strength of VTA-NAc synapses.

- In Vivo Fiber Photometry: Inject an AAV encoding a genetically encoded calcium indicator (e.g., GCaMP) into the VTA of DAT-Cre mice. Implant an optical fiber above the VTA to record population-level calcium dynamics in VTA neurons during behavioral tasks, providing a readout of neural activity.

Table 2: Key Reagents for Investigating Stress-Induced Circuit Rewiring

| Research Reagent / Tool | Function & Application in Stress Research |

|---|---|

| AAV Vectors (e.g., AAV5-syn-GCaMP8m) | Deliver genes for sensors (GCaMP, jRGECO1a) or actuators (Channelrhodopsin, Halorhodopsin) to specific cell types for monitoring or manipulating neural activity [4]. |

| Cre-Driver Mouse Lines (e.g., DAT-Cre) | Enable genetic access to specific neuronal populations (e.g., dopamine neurons) for targeted expression of transgenes [7]. |

| c-Fos Immunohistochemistry | Maps neural activity patterns in response to stress or other stimuli by labeling the protein product of the immediate-early gene c-fos [6]. |

| Fiber Photometry Systems | Allow real-time, in vivo recording of population-level neural activity (via calcium or neurotransmitter sensors) in freely behaving animals [4]. |

| Optogenetics Hardware | Used to precisely stimulate or inhibit specific neural pathways with light to establish causal roles in behavior [8]. |

| scRNA-seq | Resolves cell-type-specific transcriptional changes in response to stress, identifying novel molecular targets [9]. |

The workflow for a comprehensive circuit analysis experiment, from stress induction to data collection, is summarized below.

Implications for Antidepressant Research and Development

Understanding maladaptive circuit rewiring provides a roadmap for developing novel antidepressants and personalizing treatment.

- Predicting Treatment Response: Neuroimaging biomarkers derived from dysfunctional reward and emotion regulation circuits can predict response to antidepressants like SSRIs. A recent hierarchical graph neural network model that integrated pre-treatment neurocircuitry and clinical features achieved 76.21% accuracy in predicting remission following SSRI treatment [4]. Key predictive brain regions included the globus pallidus, putamen, hippocampus, thalamus, and anterior cingulate gyrus [4].

- Targeting Circuit Dysfunction: Treatments are increasingly evaluated based on their ability to reverse specific maladaptive changes. For instance, the efficacy of ketamine is attributed to its rapid restoration of synaptic connectivity in the PFC and hippocampus, countering the synaptic deficits induced by stress [7]. This highlights a shift from monoamine-based targeting to circuit-specific remediation.

- Guideline Adherence and Treatment Gaps: Despite the availability of evidence-based guidelines, adherence in clinical practice is often suboptimal [10]. Improving the implementation of guideline-concordant care, which may include psychotherapy, pharmacotherapy, and integrative practices, is crucial for achieving better patient outcomes [11] [10].

Chronic stress instigates maladaptive neural circuit rewiring through a complex interplay of molecular signaling pathways, leading to a functional imbalance between nodes of the limbic system. The patterns of synaptic weakening in the PFC and hippocampus, coupled with synaptic strengthening in the amygdala and NAc, create a neural substrate prone to depressive symptomatology. Modern research approaches that combine circuit manipulation, in vivo monitoring, and computational modeling are essential for deciphering this complexity. The future of antidepressant development lies in leveraging this knowledge to create interventions that directly target and rectify these pathological circuit changes, moving toward a future of personalized, circuit-informed psychiatry.

Major depressive disorder (MDD) represents one of the most substantial burdens on global public health, ranking among the leading causes of disability worldwide [12]. Despite its prevalence, the treatment of depression remains hindered by profound etiological and phenotypic heterogeneity, with current psychiatric diagnostics assigning a single label to syndromes that likely involve multiple distinct neurobiological processes [13]. This heterogeneity is reflected in strikingly low treatment success rates; the landmark STAR*D trial revealed that only approximately one-third of patients achieve remission with first-line selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI) treatment, and approximately 20% remain symptomatic despite multiple, often aggressive, interventions [14]. The prevailing "one-size-fits-all" approach to depression treatment has therefore yielded limited success, creating an urgent need for quantitative measures based on coherent neurobiological dysfunctions, or 'biotypes', to enable improved patient stratification [13].

This whitepaper proposes a circuit-based taxonomy for depression that links specific neural circuit dysfunctions to distinct symptom profiles and treatment outcomes. The approach is grounded in accumulating evidence that depression involves disruptions across multiple large-scale brain networks, including the default mode, salience, and frontoparietal attention circuits [13]. By moving beyond syndromic classification toward a neurobiologically-grounded taxonomy, we aim to provide researchers and drug development professionals with a framework for developing targeted interventions matched to specific patterns of circuit dysfunction. Such advances are crucial for advancing precision medicine in psychiatry and improving the abysmally low remission rates that have plagued conventional antidepressant development.

A Taxonomy of Depression Biotypes: Linking Circuits to Clinical Profiles

Recent research utilizing standardized functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) protocols has enabled the identification of distinct biotypes of depression and anxiety based on personalized, interpretable scores of brain circuit dysfunction [13]. In a comprehensive analysis of 801 participants with depression and anxiety when treatment-free, researchers derived six clinically distinct biotypes defined by unique profiles of intrinsic task-free functional connectivity within core brain networks, along with distinct patterns of activation and connectivity during emotional and cognitive tasks [13].

Table 1: Depression Biotypes: Circuit Dysfunctions, Symptom Profiles, and Treatment Response

| Biotype | Core Circuit Dysfunctions | Clinical Symptom Profile | Treatment Response Patterns |

|---|---|---|---|

| Biotype 1 | Hyperconnectivity in default mode network; reduced cognitive control circuit activation | Prominent anhedonia, rumination, and negative self-focus | Better response to behavioral therapy targeting rumination than standard pharmacotherapy |

| Biotype 2 | Salience network hyperconnectivity; heightened threat circuit reactivity | Severe anxiety, vigilance, threat sensitivity | Moderate response to SSRIs; potentially better response to anxiety-targeted interventions |

| Biotype 3 | Attention control network hypoconnectivity; reduced cognitive control activation | Cognitive dysfunction, impaired concentration, executive deficits | Poor response to conventional antidepressants; may benefit from cognitive-enhancing adjuncts |

| Biotype 4 | Default mode and salience network co-dysregulation; emotional task hyperreactivity | Mixed depressive-anxious symptoms with emotional lability | Moderate response to both pharmacotherapy and behavioral interventions |

| Biotype 5 | Default mode hypoconnectivity; blunted positive affect circuit activity | Apathy, anergia, blunted affect | Better response to antidepressants with activating properties |

| Biotype 6 | Mild circuit deviations across multiple networks | Milder, more heterogeneous symptoms | Good response to first-line treatments (both therapy and medication) |

These biotypes demonstrate remarkable consistency with theoretical frameworks of circuit dysfunction in depression and are distinguished by specific symptom profiles, behavioral performance on cognitive tests, and differential responses to various treatment modalities [13]. The identification of such biotypes provides a neurobiological foundation for parsing the heterogeneity of depression and represents a promising approach for advancing precision clinical care in psychiatry.

Molecular Pathways Converging on Synaptic Dysfunction in Depression

The neural circuit dysfunctions observed in depression biotypes arise from disturbances at the molecular level that ultimately converge on synaptic dysfunction. Major depressive disorder involves a complex interplay of numerous interrelated pathways, including monoamine systems, neurotrophin signaling, glutamatergic neurotransmission, inflammatory processes, and (epi)genetic regulation [12].

The monoamine theory of depression, which posited deficiencies in serotonin, norepinephrine, and dopamine signaling, has evolved to acknowledge that these neurotransmitters represent only one component of a far more complex picture [12]. While monoamine-based antidepressants remain first-line treatments, their limitations – including delayed onset of action and limited efficacy in a substantial proportion of patients – have prompted investigation into alternative mechanisms. Notably, the rapid antidepressant effects of ketamine have highlighted the crucial role of glutamate signaling and synaptic plasticity in depression pathophysiology [15].

Genetic studies have provided compelling evidence for the synaptic basis of depression. The largest genome-wide association study of depression to date, involving over 1.2 million participants, identified 178 genetic risk loci, with top biological processes including synapse assembly and function [12]. Key MDD-associated genes such as NEGR1, DRD2, and CELF4 are all implicated in the control of synaptic number, maturation, and plasticity [12]. These genetic variants likely serve as "first hits" in a multifactorial disease model, increasing vulnerability to environmental stressors that subsequently induce epigenetic modifications affecting synaptic function.

The neurotrophic hypothesis of depression, focusing particularly on brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF), provides a crucial link between molecular pathways and circuit-level dysfunction. Reduced BDNF levels in acute MDD impair synaptic support and plasticity, while effective antidepressant treatments – including both conventional medications and ketamine – increase BDNF signaling and promote synaptogenesis [12]. Recent research has demonstrated that antidepressants bind directly to the transmembrane domain of TrkB receptors, enhancing BDNF signaling and promoting synaptic connectivity [12].

Table 2: Key Molecular Pathways in Depression and Their Synaptic Targets

| Molecular Pathway | Key Components | Synaptic Actions | Experimental Modulators |

|---|---|---|---|

| Monoamine Signaling | Serotonin, norepinephrine, dopamine receptors; monoamine transporters | Modulate neurotransmitter release; regulate synaptic plasticity through G-protein coupled receptors | SSRIs, SNRIs, TCAs, MAOIs |

| Glutamatergic System | NMDA, AMPA, metabotropic glutamate receptors | Regulate excitatory neurotransmission; control synaptic plasticity and strength | Ketamine, psilocybin, AMPA potentiators |

| Neurotrophic Signaling | BDNF, TrkB, mTOR | Promote synaptogenesis; enhance synaptic plasticity and stability | TrkB agonists, mTOR modulators |

| Opioid System | μ, δ, κ opioid receptors | Modulate neurotransmitter release through potassium channel activation; influence neuronal excitability | KOR antagonists, MOR modulators |

| Inflammatory Pathways | Cytokines, CRP, microglial activation | Alter synaptic pruning; reduce synaptic plasticity | Anti-cytokine therapies, minocycline |

The convergence of these diverse molecular pathways on synaptic function provides a framework for understanding how genetic vulnerability, environmental stressors, and biological systems interact to produce the circuit-level dysfunctions observed in depression biotypes. This multi-level perspective enables researchers to connect molecular targets with systems-level approaches for drug development.

Experimental Methodologies for Circuit-Based Taxonomy Development

Neuroimaging Protocols for Biotype Identification

The identification of depression biotypes requires standardized functional magnetic resonance imaging protocols that assess both task-free and task-evoked brain circuit function. The Stanford Et Cere Image Processing System represents one such approach, quantifying circuit dysfunction at the individual participant level through 41 distinct measures of activation and connectivity across six brain circuits of interest [13]. These measures are expressed in standard deviation units from the mean of a healthy reference sample, creating interpretable personalized circuit scores that enable patient stratification.

The imaging protocol should include both task-free (resting-state) and task-evoked conditions. Task-free functional connectivity assesses intrinsic relationships between brain regions, while task-evoked fMRI probes circuit function during specific cognitive and emotional challenges. Emotional tasks typically involve viewing faces with emotional expressions or processing emotionally valenced stimuli, whereas cognitive tasks often assess attention, cognitive control, or working memory [13]. This multi-modal approach captures both the brain's intrinsic organization and its dynamic engagement during psychologically relevant processes.

For data analysis, hierarchical clustering algorithms applied to regional circuit scores can identify coherent biotypes. Validation should include multiple procedures: the elbow method for determining optimal cluster number; simulation-based significance testing of the silhouette index; stability assessment through leave-one-out and leave-20%-out cross-validation; split-half reliability of cluster profiles; and theoretical consistency with established frameworks of circuit dysfunction in depression [13]. This comprehensive validation ensures that identified biotypes reflect meaningful neurobiological distinctions rather than algorithmic artifacts.

Dynamic Functional Connectivity for Enhanced Classification

Traditional static functional connectivity (SFC) analyses, which assume temporal stationarity in correlations between regional BOLD time courses, have limitations in capturing the dynamic nature of brain function in depression. Dynamic functional connectivity (DFC) analyses using sliding-window algorithms reveal time-varying co-activation patterns that provide a more detailed description of interactions in the brain [16].

The DFC analysis protocol involves acquiring resting-state fMRI data with standard parameters (e.g., TR=2000ms, TE=30ms, flip angle=90°, FOV=240mm). Following preprocessing, a sliding-window algorithm calculates functional connectivity in successive time windows throughout the scan duration [16]. A non-linear support vector machine (SVM) classifier with recursive feature elimination (SVM-RFE) can then select optimal feature subsets for classification model development.

This approach has demonstrated remarkable efficacy in distinguishing MDD patients from healthy controls, achieving an area under the curve (AUC) of 0.9913 compared to 0.8685 for SFC-based approaches [16]. The most discriminative connections typically distribute across visual, somatomotor, dorsal and ventral attention, limbic, frontoparietal, and default mode networks, with particular importance of frontoparietal, default mode, and visual network connections [16].

Machine Learning Approaches for Multi-Modal Data Integration

Advanced artificial intelligence systems using local-global multimodal fusion graph neural networks (LGMF-GNN) can integrate functional MRI, structural MRI, and electronic health records to provide objective diagnostic methods [17]. These systems analyze both individual brain regions and population-level data, achieving classification accuracy of 78.75% and AUROC of 80.64% across multi-center cohorts [17].

Such approaches can identify distinct brain connectivity patterns in MDD, including reduced functional connectivity between the left gyrus rectus and right cerebellar lobule VIIB, and increased connectivity between the left Rolandic operculum and right hippocampus [17]. Structural analyses reveal MDD-associated thickness changes at the gray-white matter interface, indicating potential neuropathological conditions or brain injuries [17].

Diagram 1: Circuit Biotype Identification Workflow. This workflow illustrates the standardized protocol for identifying depression biotypes from neuroimaging data, culminating in clinically validated circuit-based classifications.

Visualization of Molecular Pathways and Experimental Workflows

Molecular Pathways Converging on the Synapse

The molecular etiology of depression involves numerous pathways that ultimately converge on synaptic function, representing the closest physical representation of mood, emotion, and consciousness that can be currently conceptualized [12]. The following diagram illustrates how diverse molecular systems interact to influence synaptic neurotransmission in depression.

Diagram 2: Molecular Pathways Converging on Synaptic Dysfunction. This diagram illustrates how diverse molecular systems, influenced by genetic and environmental factors, ultimately converge on synaptic function to produce circuit-level dysregulation and depression symptoms.

Dynamic Functional Connectivity Analysis Pipeline

The analysis of dynamic functional connectivity provides superior classification of MDD patients compared to traditional static approaches. The following workflow outlines the key steps in DFC analysis for depression biotyping.

Diagram 3: Dynamic Functional Connectivity Analysis Pipeline. This workflow outlines the process for analyzing dynamic functional connectivity in depression, resulting in superior classification accuracy compared to static approaches.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Essential Research Resources for Circuit-Based Depression Studies

| Resource Category | Specific Examples | Research Application | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Animal Models | Chronic mild stress (CMS), Social defeat, Chronic corticosterone | Study antidepressant response mechanisms; model treatment resistance | BALB/c mice most sensitive to UCMS; C57BL/6 slightly susceptible [14] |

| Genetic Tools | NEGR1, DRD2, CELF4 variants; CRISPR/Cas9 systems | Investigate genetic vulnerability; model specific molecular pathways | SNP-based heritability of MDD ~11.3%; highly polygenic [12] |

| Neuroimaging Protocols | Stanford Et Cere System; sliding-window DFC analysis | Quantify circuit dysfunction; identify biotypes; track treatment response | Combine task-free and task-evoked fMRI; standardized processing essential [13] [16] |

| Rapid-Acting Antidepressants | Ketamine, Psilocybin, NMDA receptor antagonists | Investigate synaptic plasticity mechanisms; fast-acting treatment models | Ketamine affects AMPA receptors, adenosine A1 receptors, L-type calcium channels [15] |

| Molecular Assays | BDNF/TrkB signaling panels; synaptic protein markers | Quantify synaptic plasticity; assess treatment effects | BDNF levels reduced in acute MDD; increase after antidepressant treatment [12] |

| Behavioral Assessments | Forced swim test, Sucrose preference, Social interaction | Model depression-like behaviors; assess treatment efficacy | Correlate with neurobiological measures; multiple tests recommended [14] |

The resources outlined in Table 3 represent essential tools for investigating the circuit basis of depression and developing the proposed taxonomy. Animal models, particularly chronic stress paradigms, enable the study of antidepressant response mechanisms and treatment resistance [14]. Genetic tools allow researchers to investigate the polygenic architecture of depression, with particular focus on genes implicated in synaptic function such as NEGR1, DRD2, and CELF4 [12].

Neuroimaging protocols form the cornerstone of circuit-based taxonomy development, with standardized systems like the Stanford Et Cere enabling quantification of circuit dysfunction at the individual participant level [13]. Complementary DFC analyses provide superior classification accuracy compared to traditional static approaches [16]. Pharmacological tools, particularly rapid-acting antidepressants like ketamine and psilocybin, facilitate investigation of synaptic plasticity mechanisms and fast-acting treatment models [15]. These resources collectively enable a multi-level approach to depression research, linking molecular mechanisms to circuit dysfunction and ultimately to clinical symptom profiles.

The proposed circuit taxonomy for depression represents a paradigm shift from symptom-based classification to neurobiologically-grounded stratification. By linking specific circuit dysfunctions to distinct symptom profiles and treatment outcomes, this approach addresses the profound heterogeneity that has long hampered depression research and treatment development. The identification of six clinically distinct biotypes, defined by unique patterns of task-free and task-evoked circuit dysfunction, provides a validated foundation for precision medicine in psychiatry [13].

Future research must further refine this taxonomy through multi-modal data integration, including genetic, molecular, and circuit-level information. The convergence of diverse molecular pathways on synaptic function [12] suggests that ultimately, effective depression treatments must target these final common pathways to restore circuit homeostasis. Rapid-acting antidepressants like ketamine have demonstrated the therapeutic potential of directly targeting synaptic plasticity mechanisms [15], offering promising directions for future drug development.

For researchers and drug development professionals, this circuit taxonomy provides a framework for designing targeted interventions matched to specific patterns of neurobiological dysfunction. Rather than continuing the "one-size-fits-all" approach that has yielded limited success, the future of depression treatment lies in matching specific circuit dysfunctions with mechanistically-targeted interventions. This approach promises to improve the tragically low remission rates that have characterized conventional antidepressant development, ultimately offering hope for the substantial proportion of patients currently failed by existing treatments.

The prefrontal-amygdala circuit is a fundamental neural system for processing threat, regulating emotional responses, and evaluating ambiguity. In major depressive disorder (MDD) and anxiety disorders, dysregulation of this circuit—particularly a state of functional hyperactivity—is a core neurobiological feature underlying symptoms of negative affect and anxious apprehension. This whitepaper synthesizes current research on the circuit's functional anatomy, quantitative signatures of its dysregulation, and detailed experimental methodologies for its investigation, framed within the context of identifying biomarkers for antidepressant response. Understanding these circuit-level changes is critical for developing targeted, mechanistically-informed treatments for mood and anxiety disorders.

Functional Neuroanatomy of the Prefrontal-Amygdala Circuit

The prefrontal-amygdala circuit integrates subcortical regions for rapid emotional processing with prefrontal areas for higher-order cognitive control. The amygdala, an almond-shaped structure in the medial temporal lobe, is comprised of subnuclei including the basolateral nucleus (BLA) and central nucleus (Ce), which have distinct functions and connectivity [18]. The amygdala detects biologically salient stimuli, orchestrates fear responses, and encodes ambiguity in the environment [19].

The medial prefrontal cortex (mPFC) is roughly divided into dorsal (dmPFC) and ventral (vmPFC) subregions relative to the corpus callosum's genu. The dmPFC (including supragenual anterior cingulate) mediates cognitive control, conflict monitoring, and emotion regulation. The vmPFC (including subgenual anterior cingulate and medial orbitofrontal cortex) facilitates fear extinction, value comparison, and social cognition [19] [18].

Anatomically, the mPFC and amygdala share reciprocal connections. The amygdala sends robust efferent projections to the mPFC, which are heavier than the reciprocal cortical afferents. The mPFC provides top-down regulation of amygdala output, primarily through inputs to the BLA and intercalated cells that inhibit BLA projections to the Ce, thereby dampening fear expression [18]. In humans, the structural integrity of this white matter pathway can be quantified using Diffusion Tensor Imaging (DTI) to measure fractional anisotropy [18].

Figure 1: Prefrontal-Amygdala Circuit Pathways. The dmPFC and vmPFC provide top-down regulation of amygdala output, particularly through inhibition of the basolateral amygdala (BLA) to central nucleus (Ce) pathway, which governs fear expression and autonomic responses.

Quantitative Signatures of Circuit Hyperactivity

Aberrant Functional Connectivity Patterns

Hyperactivity in the prefrontal-amygdala circuit manifests as altered directionality and strength of functional coupling, measurable with fMRI. In healthy individuals, stronger negative coupling between the amygdala and vmPFC typically correlates with better emotional regulation and lower anxiety. In pathological states, this coupling becomes dysregulated, showing either exaggerated negative connectivity or a reversal to positive coupling, indicating failed inhibitory control [20] [19] [18].

Table 1: Functional Connectivity Patterns in Prefrontal-Amygdala Circuitry

| Population / Condition | Amygdala-dmPFC Connectivity | Amygdala-vmPFC Connectivity | Behavioral Correlation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Healthy Adults | Moderate negative coupling during emotional tasks [19] | Strong negative coupling during threat safety discrimination [20] | Lower anxiety; better emotion regulation [18] |

| Anxious Adults | Increased positive coupling during threat appraisal [20] | Reduced negative/positive coupling during extinction recall [20] | Impaired threat-safety discrimination; higher anxiety [20] |

| Anxious Youth | Exaggerated negative coupling during threat appraisal [20] | More negative coupling during extinction recall [20] | Developmental disruption of emotion regulation [20] |

| MDD Patients | Altered effective connectivity with frontolimbic network [21] | Reduced inhibitory control [19] | Severity of anhedonia and depressed mood [4] |

| Early Life Stress (Mouse Model) | Hyperconnectivity [22] | Hyperconnectivity [22] | Increased anxiety-like behavior in open-field test [22] |

Neural Signatures of Emotion Ambiguity Processing

Processing ambiguous emotional stimuli particularly engages the prefrontal-amygdala circuit. Single-neuron recordings in neurosurgical patients show that amygdala neurons respond earlier than dmPFC neurons to emotion ambiguity, reflecting a bottom-up affective process for ambiguity representation. This is followed by dmPFC engagement, reflecting top-down cognitive processes for ambiguity resolution. In MDD and anxiety disorders, this temporal dynamics are disrupted, leading to biased interpretation of ambiguous stimuli as threatening [19].

Table 2: Quantitative fMRI and Metabolic Findings in Circuit Hyperactivity

| Brain Region | Metric | Healthy Controls | MDD/Anxiety Patients | Experimental Paradigm |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Right Amygdala | Task-based activation (post-treatment change) | N/A | Consistent decrease with successful treatment (peak MNI: 30, 2, -22) [23] | Emotion face processing tasks |

| Amygdala-vmPFC Circuit | Effective connectivity (DCM) | Balanced bottom-up/top-down | Aberrant connections to VMPFC, sgACC, NAC [21] | Resting-state fMRI |

| Amygdala-Hippocampus | Resting-state functional connectivity (rs-fMRI) | Normal range correlation | Hyperconnectivity in early stress models [22] | Rodent rsfMRI |

| dlPFC-sgACC | Theta burst stimulation response | N/A | Normalized connectivity with treatment response [21] | SAINT rTMS protocol |

Experimental Protocols for Circuit Investigation

Human Neuroimaging Protocols

Task-Based fMRI for Threat-Safety Discrimination

- Purpose: To assess amygdala-prefrontal dynamics during extinction recall and threat appraisal [20]

- Participants: Anxious vs. healthy cohorts across developmental stages (youth vs. adults)

- Task Design: Extinction recall paradigm with three attention conditions:

- Threat Appraisal: Evaluate how threatening a stimulus is

- Explicit Threat Memory: Recall previously learned threat associations

- Physical Discrimination: Perceptual judgment of stimulus characteristics (control condition)

- fMRI Acquisition: 3T scanner, T2*-weighted echo planar imaging, standardized parameters (e.g., TR=2000ms, TE=30ms, voxel size=3×3×3mm)

- Analysis: Generalized psychophysiological interaction (gPPI) to test task-dependent functional connectivity with anatomically-defined amygdala seeds

- Statistical Modeling: Whole-brain analyses with ANOVA examining interactions between anxiety diagnosis, age group, and attention task

Dynamic Causal Modeling (DCM) for Effective Connectivity

- Purpose: Estimate causal relationships among depression-related regions [21]

- Participants: Large sample sizes (e.g., 270 healthy controls, 175 MDD patients) for adequate power

- Data Acquisition: Multi-site resting-state fMRI with standardized protocols

- ROI Selection: Focus on regions functionally connected to left DLPFC: amygdala, nucleus accumbens, anterior insula, sgACC, and VMPFC

- Model Specification: Define a priori model of network architecture based on depression circuitry literature

- Parameter Estimation: Bayesian inversion to estimate directed connectivity between regions

- Statistical Analysis: Parametric empirical Bayes for between-group comparisons (MDD vs. controls)

Animal Model Protocols

Unpredictable Postnatal Stress (UPS) Model

- Purpose: Investigate effects of early-life stress on amygdala-prefrontal connectivity and anxiety-like behavior [22]

- Subjects: C57BL/6 mice, with precise genetic background control

- Stress Paradigm: From postnatal days 1-14, expose pups to unpredictable stressors in a variable sequence:

- Cage tilting

- Wet bedding

- Social isolation

- Predator odor

- Light cycle alterations

- Behavioral Testing: In juvenile and adult stages, using:

- Open-field test (anxiety-like behavior)

- Elevated plus maze (anxiety-like behavior)

- rsfMRI Acquisition: In adult males, under isoflurane anesthesia

- Connectivity Analysis: Seed-based correlation focusing on amygdala-prefrontal and amygdala-hippocampus pathways

- Correlation Analysis: Relationship between connectivity strength and anxiety-like behavior metrics

Figure 2: Unpredictable Postnatal Stress Experimental Workflow. This protocol induces frontolimbic hyperconnectivity and anxiety-like behavior in mouse models, mimicking features of human anxiety and depression.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Resources

| Resource Category | Specific Examples | Research Application | Key Function |

|---|---|---|---|

| Animal Models | Unpredictable Postnatal Stress (UPS) mice [22] | Early life stress research | Induces amygdala-prefrontal hyperconnectivity |

| Chronic Mild Stress (CMS) models [14] | Depression pathophysiology & treatment response | Models anhedonia & antidepressant response | |

| Genetic Tools | BALB/c vs C57BL/6 mouse strains [14] | Stress susceptibility studies | Differential sensitivity to UCMS procedures |

| Neuroimaging Databases | DecNef Project Brain Data Repository [21] | Multi-site fMRI studies | Large-sample, standardized neuroimaging data |

| SRPBS dataset (AMED) [21] | MDD biomarker discovery | Japanese population neuroimaging data | |

| Behavioral Paradigms | Fear extinction recall with attention modulation [20] | Threat processing in anxiety | Tests anxiety & age effects on amygdala-PFC coupling |

| Fear-happy morph emotion judgment [19] | Emotion ambiguity processing | Assesses amygdala-dmPFC-vmPFC network dynamics | |

| Analysis Tools | Generalized Psychophysiological Interaction (gPPI) [20] | Task-based functional connectivity | Measures context-dependent connectivity changes |

| Dynamic Causal Modeling (DCM) [21] [19] | Effective connectivity estimation | Models directional influences between brain regions | |

| Graph Neural Networks (GNNs) [4] | Treatment response prediction | Integrates multimodal data for outcome prediction |

Implications for Antidepressant Response Research

Circuit-level dysfunction in the prefrontal-amygdala pathway represents a promising biomarker for predicting and monitoring treatment response in depression and anxiety disorders. A 2025 meta-analysis of task-based fMRI studies across 302 depressed patients revealed that successful treatment with various modalities (pharmacotherapy, psychotherapy, ECT, psilocybin, ketamine) consistently normalizes hyperactivity in the right amygdala (peak coordinates: 30, 2, -22) [23]. This convergence suggests that despite different mechanisms of action, effective treatments share a common neural pathway of dampening amygdala hyperreactivity.

Advanced computational approaches are now leveraging these circuit biomarkers to predict individual treatment outcomes. Hierarchical graph neural network (GNN) models integrating baseline neuroimaging and clinical features can predict SSRI remission with 76.21% accuracy by analyzing dysfunction in reward and emotion regulation circuits [4]. Key contributing regions include the amygdala, hippocampus, thalamus, and anterior cingulate gyrus, highlighting the importance of distributed circuit-level assessment rather than single-region biomarkers.

Neuromodulation treatments specifically target this dysregulated circuitry. Repetitive TMS applied to the left DLPFC exerts its antidepressant effects by remotely modulating the broader depression network, including amygdala, sgACC, VMPFC, and nucleus accumbens [21]. The recently developed SAINT protocol uses accelerated intermittent theta burst stimulation to normalize causal connections between the sgACC, anterior insula, and amygdala, demonstrating how precise circuit targeting can enhance treatment efficacy [21].

The directionality of amygdala-prefrontal connectivity may also serve as a treatment selection biomarker. Patients with predominantly bottom-up amygdala-driven pathology may respond better to treatments that directly target amygdala hyperactivity (e.g., ketamine), while those with top-down regulatory deficits may benefit more from prefrontal-focused interventions (e.g., rTMS, cognitive remediation therapy) [19] [24]. This circuitry-based stratification approach represents a promising path toward personalized neurotherapeutics for depression and anxiety disorders.

The hippocampus and nucleus accumbens (NAc) form a critical neural circuit within the brain's limbic system, integrating cognitive processes with motivational and reward pathways. In major depressive disorder (MDD), and particularly in its melancholic and anhedonic subtypes, dysfunction of this circuit is increasingly recognized as a core neurobiological feature. This whitepaper synthesizes current research demonstrating how hypoactivity within the hippocampus-NAc pathway contributes to the pathophysiology of anhedonia—the diminished capacity to experience pleasure—and explores the implications of these findings for antidepressant development and circuit-based therapeutics.

Converging evidence from preclinical models and human neuroimaging reveals that chronic stress induces maladaptive plasticity and functional deficits in this circuit, disrupting reward processing and approach behavior. The ventral hippocampus (vHPC), through its glutamatergic projections to the NAc shell, plays a particularly crucial role in resolving approach-avoidance conflicts and guiding reward-seeking behaviors. When this circuit becomes hypoactive, it produces a behavioral bias toward avoidance and diminished motivation for rewards, clinically manifesting as anhedonia. Understanding these mechanisms provides a foundation for developing targeted interventions that normalize circuit function for patients with treatment-resistant depression.

Anatomical and Functional Basis of the Hippocampus-NAc Circuit

Circuit Architecture and Connectivity

The hippocampus-NAc circuit originates primarily from the ventral region of the hippocampus (anterior in humans), which projects strongly to the shell subregion of the NAc via glutamatergic pathways [25] [26]. This pathway represents a key anatomical substrate through which cognitive and contextual information from the hippocampus modulates motivated behavior through the striatal reward system. The vHPC-NAc shell projection predominantly targets GABAergic medium spiny neurons in the NAc, which integrate these hippocampal inputs with signals from prefrontal cortex, amygdala, and ventral tegmental area to regulate behavioral output [27].

The circuit exhibits functional topography, with the vHPC-NAc pathway specifically implicated in approach behaviors during motivational conflict. Chemogenetic inhibition of this pathway increases decision-making time and promotes avoidance bias when animals face stimuli with competing positive and negative valences [25] [26]. This demonstrates its critical role in arbitrating approach-avoidance conflicts—a process fundamentally disrupted in anhedonia.

Functional Role in Reward Processing and Motivation

The vHPC-NAc circuit functions as a contextual reward integrator, translating learned environmental associations into motivated action selection. During reward-seeking behavior, neuronal populations in the vHPC and NAc exhibit coordinated activation patterns that predict and guide reward choices [28]. In stress-resilient animals, these circuits show robust discrimination between different reward options, whereas susceptible animals display altered dynamics characterized by impaired reward discrimination and enhanced "switch-stay" intention states [28].

Table 1: Key Functional Attributes of the Hippocampus-NAc Circuit

| Functional Attribute | Biological Substrate | Behavioral Manifestation |

|---|---|---|

| Approach-avoidance arbitration | vCA1 to NAc shell projections | Resolution of motivational conflict |

| Reward valuation | Integrated hippocampal-accumbens activity | Preference for high-value rewards |

| Contextual reward learning | Hippocampal contextual input to NAc | Environment-appropriate reward seeking |

| Motivational drive | Glutamatergic excitation of NAc neurons | Sustained goal-directed behavior |

Mechanisms of Circuit Dysfunction in Anhedonia

Stress-Induced Hypoactivity and Synaptic Deficits

Chronic stress exposure, a key predisposing factor for depression, induces structural and functional maladaptations in the hippocampus-NAc circuit. In animal models of depression, chronic unpredictable mild stress (CUMS) significantly reduces hippocampal high gamma oscillation power and synaptic spine density in both hippocampus and NAc-projecting regions [27]. These morphological changes correlate with behavioral manifestations of anhedonia, including reduced sucrose preference and social interaction.

At the molecular level, stress-induced circuit hypoactivity involves impaired neurotrophic signaling and synaptic protein synthesis. CUMS reduces expression of brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF), postsynaptic density protein-95 (PSD-95), and phosphorylation of key signaling molecules in the AKT/mTOR pathway [27]. This pathway is essential for protein synthesis-dependent synaptic plasticity, and its disruption provides a mechanistic link between stress exposure and circuit hypoactivity.

Altered Neural Dynamics in Reward Processing

Recent high-density electrophysiology studies reveal distinctive population-level neural signatures in the hippocampus-NAc circuit that differentiate stress-resilient from susceptible animals. When actively seeking rewards, resilient animals exhibit robust discrimination between reward choices in ventral hippocampal and basolateral amygdala activity patterns [28]. In contrast, susceptible animals show a rumination-like signature characterized by enhanced encoding of intention to switch or stay on a previously chosen reward, reflecting maladaptive decision-making processes underlying anhedonic behavior [28].

During rest periods, susceptible animals display a greater number of distinct neural population states in spontaneous activity, allowing researchers to decode stress history and susceptibility status with greater accuracy than from behavioral measures alone [28]. This suggests that circuit-level biomarkers may provide more sensitive indicators of anhedonic vulnerability than traditional behavioral assessments.

Quantitative Evidence from Preclinical and Clinical Studies

Preclinical Findings on Circuit Manipulations

Table 2: Experimental Evidence from Preclinical Studies of the Hippocampus-NAc Circuit

| Experimental Manipulation | Model System | Key Quantitative Findings | Behavioral Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|

| Chemogenetic inhibition of vCA1-NAc shell pathway | Long Evans rats [25] [26] | ↓ c-Fos+ cells in NAc shell (p<0.001); No change in core (p=0.54) | ↑ decision time; ↑ avoidance bias; ↓ social interaction |

| Deep brain stimulation of NAc (NAc-DBS) | CUMS mouse model [27] | Restores high gamma power; ↑ synaptic spine density; ↑ PSD-95, BDNF, p-AKT, p-mTOR | Attenuates depressive-like behaviors |

| vCA1-BLA circuit manipulation | Stress-susceptible mice [28] | Alters population dynamics; enhances reward discrimination | Reverses anhedonic behavior |

| mTOR inhibition with Rapamycin | CUMS mice with NAc-DBS [27] | Blocks NAc-DBS-induced increases in synaptic proteins | Moderates antidepressant effects of DBS |

Human Neuroimaging Evidence

Human neuroimaging studies provide translational validation of preclinical findings, demonstrating functional alterations in the hippocampus-NAc circuit across depressive subtypes. Resting-state functional connectivity (FC) studies reveal that melancholic depression, characterized by profound anhedonia, is associated with increased FC between the NAc and middle frontal gyrus compared to non-melancholic depression [29]. This hyperconnectivity may represent a compensatory mechanism or maladaptive reorganization in response to circuit hypoactivity elsewhere.

Large-scale analyses have identified that altered reward circuit connectivity patterns can stratify patients into distinct biotypes with differential treatment responses. One study classified six biologically distinct subtypes of depression and anxiety based on circuit dysfunction profiles, including patterns of intrinsic connectivity within the default mode, salience, and frontoparietal attention circuits [13]. These biotypes showed distinct symptom profiles and responded differently to pharmacotherapy and behavioral interventions, highlighting the translational potential of circuit-based stratification.

A coordinate-based meta-analysis of treatment studies found that successful intervention across multiple treatment modalities was associated with normalization of right amygdala activity [23], a region interconnected with both hippocampus and NAc, suggesting that downstream effects on extended circuit dynamics may be crucial for therapeutic efficacy.

Methodological Approaches for Circuit Investigation

Experimental Protocols and Workflows

Chronic Unpredictable Mild Stress (CUMS) Protocol: The CUMS paradigm involves exposing animals to a variety of stressors over 14 days, including both short-term stimuli (1-hour restraint, 1-hour cold exposure, 5-minute heat exposure, 4-hour pepper smell exposure, 20-minute cage shaking, 2-minute tail pinch) and long-term stimuli (24-hour food/water deprivation, cage tilting, bedding removal) [27]. Animals are exposed to randomly selected stimulus combinations daily, preventing habituation. Behavioral assessments (sucrose preference, social interaction, forced swim) are conducted pre- and post-stress, with neurobiological measures taken post-mortem.

Circuit-Specific Neuronal Inhibition: Pathway-specific chemogenetic inhibition involves transducing vCA1 neurons with inhibitory DREADDs (hM4Di-mCherry) via AAV delivery, combined with cannula implantation in NAc shell for later microinfusion of CNO or saline [25] [26]. After recovery, animals undergo behavioral testing during which CNO administration selectively inhibits the vCA1-NAc pathway. Control groups receive empty vector (GFP) with similar CNO administration. Efficacy of manipulation is verified through c-Fos immunohistochemistry and histological confirmation of electrode placements.

Deep Brain Stimulation Parameters: For NAc-DBS, electrodes are implanted bilaterally in the Nac core using stereotaxic surgery [27]. After recovery from CUMS exposure, animals receive high-frequency stimulation (typically 100-200 Hz, 100-200 μA, 60-100 μs pulse width) for specified periods. Control groups undergo sham stimulation with implanted electrodes but no current delivery. Behavioral tests are conducted during and after stimulation periods, followed by electrophysiological recordings and molecular analyses.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions

Table 3: Key Research Reagents for Investigating the Hippocampus-NAc Circuit

| Reagent/Solution | Primary Function | Application Examples |

|---|---|---|

| DREADDs (Designer Receptors Exclusively Activated by Designer Drugs) | Chemogenetic control of neuronal activity | Pathway-specific inhibition of vCA1-NAc projections [25] [26] |

| AAV Vectors (Serotypes 1, 5, 8) | Targeted gene delivery to specific cell populations | Expression of fluorescent reporters, optogenetic tools, DREADDs in circuit neurons |

| Clozapine N-Oxide (CNO) | Pharmacological activation of DREADDs | Selective inhibition of hM4Di-expressing neurons during behavioral tasks |

| Neuropixels Probes | High-density electrophysiology recording | Simultaneous monitoring of hundreds of neurons in BLA and vCA1 [28] |

| Rapamycin | Specific mTOR pathway inhibition | Blocking protein synthesis-dependent synaptic plasticity [27] |

| Golgi-Cox Staining Solution | Neuronal morphology visualization | Quantifying dendritic spine density and complexity [27] |

| c-Fos Antibodies | Neural activity mapping | Identifying recently activated neurons following behavioral tasks |

Signaling Pathways Mediating Circuit Plasticity

The AKT/mTOR/BDNF signaling pathway has been identified as a crucial molecular mechanism underlying synaptic plasticity in the hippocampus-NAc circuit and its response to neuromodulation [27]. Under normal conditions, activity-dependent BDNF release activates AKT, which in turn stimulates mTOR-mediated protein synthesis, leading to enhanced synaptic spine formation and strengthened circuit connectivity.

In depression models, chronic stress reduces BDNF expression and decreases phosphorylation of AKT and mTOR, resulting in synaptic spine loss and circuit hypoactivity. Deep brain stimulation of the NAc reverses these effects, potentially through increased BDNF protein expression and activation of the AKT/mTOR signaling pathway [27]. The specific mTOR inhibitor rapamycin blocks these synaptic and behavioral effects, confirming the pathway's essential role.

Implications for Therapeutic Development

Circuit-Targeted Interventions

The delineation of hippocampus-NAc circuit dysfunction in anhedonia opens promising avenues for targeted therapeutic development. Deep brain stimulation of the NAc has demonstrated efficacy in reversing both behavioral and neurobiological correlates of anhedonia in preclinical models [27]. Clinical studies of NAc-DBS for treatment-resistant depression have reported symptom improvement, particularly for anhedonic features [29].

Emerging brain-circuit-based biotyping approaches offer a framework for personalizing these interventions. By stratifying patients according to distinct patterns of circuit dysfunction, including hippocampus-NAc connectivity profiles, clinicians may better match individuals to optimal treatments [13]. For example, patients with prominent hypoactivity in reward circuits might preferentially benefit for interventions that directly target these pathways.

Biomarker Development and Personalized Approaches

Quantitative electroencephalography (QEEG) and functional connectivity measures show promise as translational biomarkers for circuit dysfunction. QEEG patterns such as frontal alpha asymmetry and altered gamma band power may provide accessible proxies for hippocampus-NAc circuit function [30]. Similarly, resting-state fMRI measures of NAc connectivity with hippocampal and frontal regions can identify patient subtypes most likely to respond to targeted treatments [31] [29].

Advanced computational approaches, including graph neural networks applied to neuroimaging data, are improving prediction of treatment response based on circuit dysfunction patterns [4]. These methods can integrate multiple data modalities to identify complex, multivariate signatures of circuit dysfunction that transcend traditional diagnostic boundaries.

The hippocampus-NAc circuit represents a critical nexus where cognitive, contextual, and emotional information converges to guide motivated behavior. Hypoactivity within this circuit, induced by chronic stress and mediated through impaired neurotrophic signaling and synaptic plasticity, underlies the profound reward processing deficits characteristic of anhedonia in depression.

Recent methodological advances in circuit-specific manipulation and population-level neural dynamics analysis have provided unprecedented insight into the mechanisms of circuit dysfunction and recovery. The development of circuit-based biotypes and targeted neuromodulation approaches holds promise for more effective, personalized interventions for treatment-resistant depression. Future research should focus on translating these preclinical findings into clinical applications, particularly for patients whose anhedonic symptoms remain refractory to conventional treatments.

The Default Mode Network (DMN), a large-scale brain network active during rest and self-referential thought, has emerged as a critical neural substrate in the pathophysiology of major depressive disorder (MDD). Its intuitive link to depressive rumination—a recurrent, self-reflective, and often uncontrollable focus on one's depressed mood and its causes—has positioned it as a primary focus in the search for neural circuitry changes underlying depression [32]. A core and replicated finding in this domain is DMN hyperconnectivity, an aberrant increase in functional connectivity between its constituent regions and with other neural structures, which often predicts levels of depressive rumination [32]. This whitepaper synthesizes current evidence on DMN hyperconnectivity, detailing its quantitative characterization, its specific association with ruminative processes, and its implications for antidepressant response research, thereby framing it within the broader context of neural circuitry changes in depression.

Quantitative Characterization of DMN Hyperconnectivity in MDD

Meta-analyses of resting-state functional magnetic resonance imaging (rs-fMRI) studies provide robust evidence for specific patterns of aberrant DMN connectivity in MDD. The hyperconnectivity is not global but involves distinct pathways, particularly those integrating the DMN with limbic regions.

Table 1: Reliably Increased Functional Connectivity in MDD from Meta-Analysis

| Connected Regions | Nature of Connectivity Change | Association with Symptomatology |

|---|---|---|

| DMN Subgenual Prefrontal Cortex (sgPFC) | Reliably increased functional connectivity | Often predicts higher levels of depressive rumination [32] |

| DMN Medial-Dorsal Thalamus (MDT) | Reliably increased functional connectivity | Implicated in information integration [32] |

| DMN Dorsal Anterior Cingulate Cortex (dACC) | Reliably increased functional connectivity | Part of the salience network [32] |

| Posterior Cingulate Cortex (PCC) sgACC | Higher ROI-to-ROI FC in antidepressant responders | Suggests role in treatment response [33] |

Furthermore, the dynamics of DMN connectivity are also impaired in MDD. A two-sample confirmation study demonstrated greater connectivity variability between the medial prefrontal cortex (mPFC) and the posterior cingulate cortex (PCC) in MDD patients compared to healthy controls. This finding, replicated across two independent samples, indicates that alterations within the DMN in MDD extend beyond static connectivity strength to include reduced temporal stability [34].

Table 2: Dynamic Functional Connectivity Changes in the DMN in MDD

| Connectivity Measure | Finding in MDD | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|

| mPFC-PCC Connectivity Stability | Reduced stability (increased variability) over time [34] | Reflects a fluctuating, unstable DMN subsystem critical for self-referential thought |