Invasive vs. Non-Invasive Neural Interfaces: A Comparative Analysis for Researchers and Clinicians

This article provides a comprehensive comparative analysis of invasive and non-invasive neural interfaces (NIs), tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals.

Invasive vs. Non-Invasive Neural Interfaces: A Comparative Analysis for Researchers and Clinicians

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive comparative analysis of invasive and non-invasive neural interfaces (NIs), tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals. It explores the fundamental principles, signal characteristics, and technological underpinnings of both approaches. The scope extends to their current methodological applications in clinical practice and research, an examination of the technical and optimization challenges each faces, and a direct, evidence-based comparison of their performance, market trajectories, and validation benchmarks. The goal is to offer a foundational resource for strategic decision-making in neurotechnology research and development.

Core Principles and Signal Foundations of Neural Interfaces

Brain-computer interfaces (BCIs) represent a rapidly evolving neurotechnology that enables direct communication between the brain and external devices [1] [2]. These systems create an alternative communication pathway by decoding neural signals associated with mental states or movement intentions, translating them into commands for controlling computers, prosthetic limbs, or other assistive devices [2]. The field has progressed substantially from early demonstrations in animals to human clinical trials, with potential applications spanning from restoring communication for paralyzed patients to revolutionary human-computer interaction paradigms [1] [3].

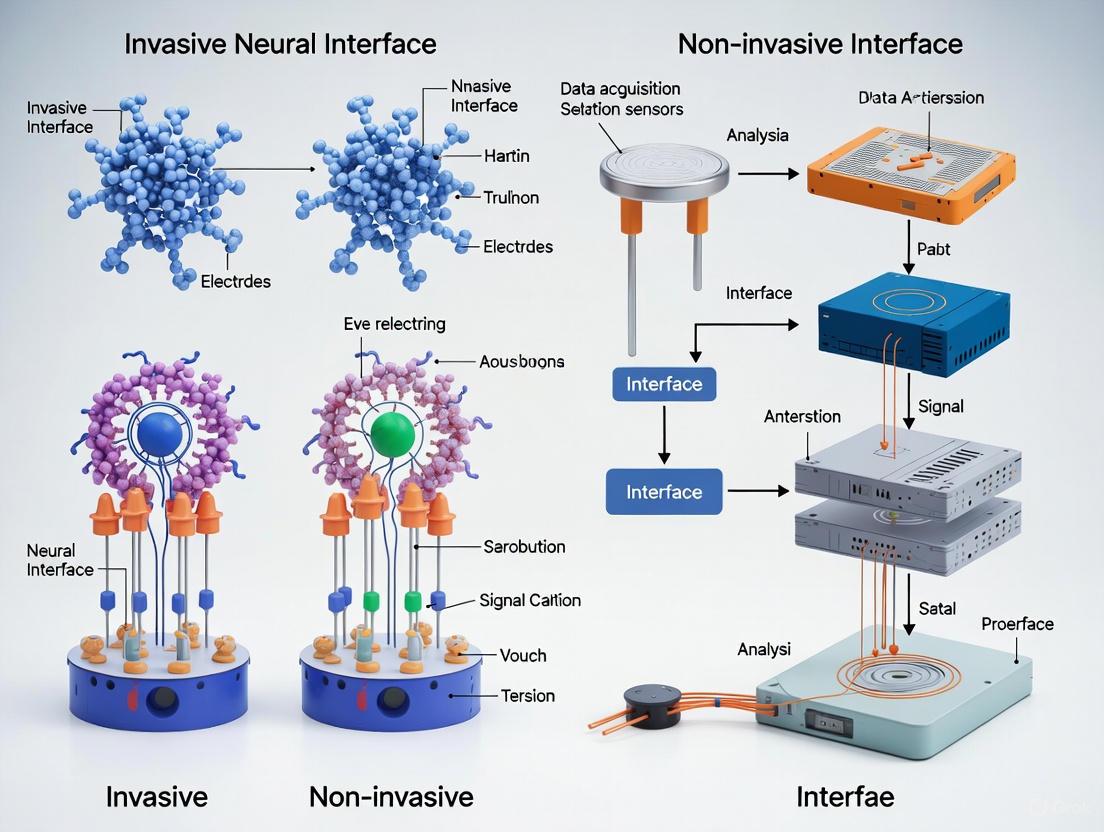

BCI technologies exist along a spectrum of invasiveness, each with distinct trade-offs between signal quality, risk, and clinical applicability [4] [2]. Non-invasive approaches record neural signals from outside the skull, typically using electroencephalography (EEG) or other external sensors [1] [5]. Invasive approaches require surgical implantation of electrodes directly onto or into brain tissue, providing higher-fidelity signals but carrying greater risk [1] [3]. A middle category of minimally invasive technologies has also emerged, including endovascular electrodes and thin-film cortical surfaces, which aim to bridge the gap between signal quality and safety [3] [2]. This review provides a comparative analysis of these approaches, focusing on their performance characteristics, experimental methodologies, and potential research applications.

Technology Classification and Signal Characteristics

Neural interfaces can be categorized based on their level of invasiveness, which directly correlates with their spatial resolution, signal-to-noise ratio, and clinical risk profile [4]. The fundamental distinction lies in whether the recording device requires penetration of the skull and/or neural tissue.

Table 1: Classification of Neural Interface Technologies by Level of Invasiveness

| Category | Technology Examples | Implantation Site | Spatial Resolution | Temporal Resolution | Key Advantages | Primary Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Non-Invasive | EEG [1] [5], fNIRS [4], Wearable MEG [4] | Scalp surface | Low (~1 cm) | High (ms) | Minimal safety risk, Easy application, Suitable for large populations [2] | Low signal-to-noise ratio, Limited spatial resolution, Susceptible to artifacts [1] [6] |

| Minimally Invasive | ECoG [2], Stentrode [2], Layer 7 Cortical Interface [3] | Brain surface or blood vessels | Medium (mm-cm) | High (ms) | Better signal quality than non-invasive, Reduced tissue damage compared to penetrating electrodes [3] [2] | Still requires surgical procedure, Limited long-term stability data |

| Invasive | Utah Array [1] [3], Neuralink [3], Neuropixels [2] | Brain parenchyma | High (μm-mm) | High (ms) | Highest signal quality, Access to single-neuron activity [3] [2] | Significant tissue damage, Scar formation over time, Ethical concerns [1] [3] |

The relationship between these technologies and their recording locations within the neural hierarchy can be visualized as follows:

Performance Comparison: Quantitative Metrics

The performance of neural interfaces is quantitatively evaluated using metrics such as information transfer rate (ITR), classification accuracy, and signal-to-noise ratio. These metrics enable direct comparison across technologies and research groups.

Information Transfer Rates Across Modalities

Information transfer rate (ITR), measured in bits per minute (bpm), provides a standardized measure of communication bandwidth that accounts for both speed and accuracy [1]. This metric allows direct comparison across different BCI technologies and experimental paradigms.

Table 2: Performance Comparison of Neural Interface Technologies

| Technology | Representative Study/System | Task | Information Transfer Rate | Classification Accuracy | Key Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Non-Invasive (EEG) | SSVEP Speller [5] | Character selection | 80.41 bpm (mean) | 75.37% (mean) | Communication, Environmental control [5] |

| Non-Invasive (sEMG) | Wristband Interface [6] | Handwriting | ~20.9 words/minute | >90% | Human-computer interaction, Handwriting decoding [6] |

| Minimally Invasive (ECoG) | WIMAGINE System [2] | Motor control for exoskeleton | N/A | Successful walking restoration | Robotic exoskeletons, Motor restoration [2] |

| Invasive (Utah Array) | BrainGate/Clinical Trials [1] [3] | Robotic arm control, Cursor control | Highly variable | High success in demonstrations | Prosthetic control, Communication for paralysis [1] |

| Invasive (Neuralink) | Neuralink [3] | Neural recording | Higher bandwidth than Utah arrays | High single-neuron resolution | High-density neural recording, Device control [3] |

Signal Characteristics and Resolution Trade-offs

The fundamental trade-offs between invasiveness and signal quality can be visualized through their relative spatial and temporal resolution characteristics:

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Non-Invasive BCI Protocols (EEG-based Systems)

Non-invasive BCI research typically employs standardized experimental paradigms to ensure reproducible results. The steady-state visual evoked potential (SSVEP) speller protocol represents a well-established methodology [5]:

Visual Stimulation Protocol: Participants focus attention on characters displayed on a screen that flicker at specific frequencies (typically 10.0-15.4 Hz range) [5]. The flicker period is typically 1.50 seconds followed by a 0.75-second flicker-free interval to reduce visual fatigue [5].

Signal Processing Workflow: EEG signals are processed using filter-bank canonical correlation analysis (CCA) to identify frequency components corresponding to the attended character [5]. This method improves signal-to-noise ratio by optimizing spatial filters for SSVEP detection.

Performance Assessment: Classification accuracy is calculated based on character selection success rate, with information transfer rate derived using the formula: ITR = [log₂N + Plog₂P + (1-P)log₂((1-P)/(N-1))]/T, where N represents number of choices, P represents classification accuracy, and T represents selection time per character [5].

Invasive BCI Protocols (Intracortical Systems)

Invasive BCI methodologies involve surgical implantation followed by signal acquisition and decoding:

Surgical Implantation: Utah arrays or similar multi-electrode arrays are surgically implanted in motor-related areas (primary motor cortex, posterior parietal cortex) [3] [2]. These arrays typically contain up to 100 needle-like electrodes that penetrate the cortical surface [3].

Neural Signal Acquisition: Systems record multi-unit activity (MUA) or single-unit activity from hundreds of recording sites simultaneously [2]. Modern systems like Neuralink contain over a thousand electrodes distributed over polymer threads implanted by specialized surgical robots [3].

Decoder Calibration: Participants perform imagined or attempted movements while neural activity is recorded [1]. Machine learning algorithms (typically linear decoders or neural networks) map neural patterns to movement parameters through closed-loop calibration [1] [2].

Performance Validation: Systems are tested using center-out reaching tasks where participants control robotic arms or computer cursors to acquire targets [1]. Performance is quantified by success rate, completion time, and path efficiency.

The complete experimental workflow for developing and validating neural interfaces follows a systematic process:

Research Reagent Solutions and Essential Materials

Successful neural interface research requires specialized materials and equipment. The following table details key components essential for experimental work in this field.

Table 3: Essential Research Materials for Neural Interface Studies

| Category | Specific Material/Device | Research Function | Key Specifications | Representative Examples |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Electrode Technologies | Dry EEG Electrodes [4] | Non-invasive neural recording | No gel requirement, Rapid application | Consumer EEG devices |

| Wet EEG Electrodes [4] | High-quality non-invasive recording | Traditional gel-based, Higher signal quality | Research-grade EEG systems | |

| Utah Array [1] [3] | Invasive single-neuron recording | 100+ electrodes, Standardized manufacturing | Blackrock Neurotech [3] | |

| Flexible Thread Electrodes [3] | Minimally invasive recording | 1024+ electrodes, Reduced tissue damage | Neuralink, Precision Layer 7 [3] | |

| Signal Acquisition Systems | EEG Amplifiers [5] | Signal conditioning and digitization | High input impedance, Low noise | Research-grade EEG systems |

| Wireless ECoG Systems [2] | Minimally invasive chronic recording | Implantable, Wireless data transfer | WIMAGINE Device [2] | |

| Neuropixels Probes [2] | High-density neural recording | Thousands of recording sites, CMOS technology | Neuropixels [2] | |

| Decoding Algorithms | Filter-Bank CCA [5] | SSVEP frequency detection | Multi-frequency analysis, Enhanced SNR | SSVEP Speller Systems [5] |

| Deep Learning Networks [6] | sEMG gesture decoding | Cross-user generalization, Real-time processing | sEMG Wristband Decoders [6] | |

| Linear Decoders [1] | Motor parameter extraction | Real-time capability, Robust performance | Robotic Arm Control [1] | |

| Validation Tools | Motion Capture Systems [6] | Movement tracking for ground truth | High spatial precision, Multi-camera | sEMG validation [6] |

| Robotic Manipulanda [1] | Device performance assessment | Programmable targets, Precision control | Center-Out Task Equipment [1] |

The spectrum from non-invasive to invasive neural interfaces presents researchers with fundamental trade-offs between signal quality, clinical risk, and practical implementation. Non-invasive technologies offer safer, more accessible options but with limited information bandwidth, while invasive approaches provide superior signal quality at the cost of surgical risk and potential tissue damage [1] [2]. Emerging minimally invasive technologies aim to bridge this gap, showing promising results in recent clinical studies [3] [2].

Future development in neural interfaces will likely focus on improving information transfer rates through advanced signal processing and electrode design [1] [4]. For invasive systems, key challenges include improving long-term stability and reducing tissue damage [3]. For non-invasive systems, priority areas include enhancing signal-to-noise ratio and developing more intuitive control paradigms [6] [5]. The field continues to evolve rapidly, with both approaches finding complementary roles in the expanding landscape of human-machine interaction and clinical neurotechnology.

The advancement of neuroscience and neurotechnology hinges on the precise acquisition and interpretation of neural signals. Researchers and clinicians have at their disposal a spectrum of tools, each with distinct mechanisms for measuring brain activity. These techniques can be broadly categorized as non-invasive, such as electroencephalography (EEG) and functional near-infrared spectroscopy (fNIRS), which record from outside the skull, and invasive, such as electrocorticography (ECoG) and intracortical signals, which require surgical implantation to record from the brain's surface or from within its tissue. The choice between these methods involves critical trade-offs concerning signal origin, spatial and temporal resolution, invasiveness, and suitability for specific applications. This guide provides a comparative analysis of these four pivotal signal types, offering a structured overview of their acquisition, origins, and experimental use to inform research and development in academia and industry.

Fundamental Principles and Signal Origins

Understanding the biological and physical principles behind each signal is the first step in selecting the appropriate tool.

EEG (Electroencephalography): EEG measures the electrical activity of populations of neurons, primarily the postsynaptic potentials of cortical pyramidal cells. When these neurons fire synchronously, their summed electrical currents create potential differences that can be detected on the scalp [7] [8]. The signal is characterized by voltage fluctuations in the microvolt (µV) range.

fNIRS (functional Near-Infrared Spectroscopy): fNIRS is an optical technique that measures the hemodynamic response, or changes in blood oxygenation, coupled with neural activity. It uses near-infrared light to detect concentration changes in oxygenated (HbO) and deoxygenated hemoglobin (HbR) in the cortical vasculature [9] [7]. This provides an indirect measure of brain activity.

ECoG (Electrocorticography): ECoG records electrical signals from the surface of the cerebral cortex (electrocorticography). Like EEG, it captures population-level electrical activity, but without the signal attenuation and spatial blurring caused by the skull and scalp [10]. This results in signals with a higher amplitude and broader frequency bandwidth than EEG.

Intracortical Signals: These signals are acquired via microelectrodes implanted directly into the brain tissue. They can capture two primary types of signals: Local Field Potentials (LFPs), which are low-frequency signals representing the summed synaptic activity of a local neuronal population, and Action Potentials (APs or "spikes"), which are high-frequency signals from the firing of individual neurons near the electrode tip [10] [8].

The diagram below illustrates the anatomical origins of these different signals.

Figure 1: A cross-sectional view of the head showing the anatomical recording locations for EEG, fNIRS, ECoG, and intracortical signals.

Technical Specifications and Comparative Analysis

The fundamental differences in signal origin directly translate into varied technical performance profiles. The table below provides a quantitative and qualitative comparison of the four modalities.

Table 1: Comprehensive comparison of neural signal acquisition technologies.

| Feature | EEG | fNIRS | ECoG | Intracortical |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Signal Origin | Postsynaptic potentials (Pyramidal neurons) [8] | Hemodynamic response (HbO/HbR) [7] | Cortical surface potentials [10] | Local Field Potentials (LFPs) & Action Potentials (Spikes) [10] |

| Spatial Resolution | Low (Centimeter-level) [7] | Moderate (Better than EEG) [7] | Medium (1-10 mm) [10] | High (50-100 μm) [10] |

| Temporal Resolution | High (Milliseconds) [7] | Low (Seconds) [7] | High (Milliseconds) | Very High (Milliseconds to kHz) [10] |

| Depth of Measurement | Cortical surface [7] | Outer cortex (1-2.5 cm) [7] | Cortical surface | Intracortical layers |

| Invasiveness | Non-invasive | Non-invasive | Invasive (Craniotomy, subdural) [10] | Highly Invasive (Penetrating tissue) [10] |

| Key Advantage(s) | Excellent temporal resolution, portable, low cost [7] | Good spatial resolution, motion-tolerant [7] | High signal quality, broad frequency range [10] | Highest spatial & temporal resolution, single-neuron access [10] |

| Primary Limitation(s) | Poor spatial resolution, sensitive to artifacts [7] | Low temporal resolution, indirect measure [7] | Requires craniotomy, limited spatial specificity [10] | Tissue response, signal stability over time [10] |

| Typical Applications | ERP studies, sleep research, brain-state monitoring [7] | Naturalistic studies, child development, rehabilitation [7] [11] | Surgical mapping, basic motor control [10] | Fine dexterous control, complex communication [10] |

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Robust experimental design is critical for acquiring high-quality data. Below are detailed protocols for a classic motor task across the different modalities, highlighting key methodological steps.

Protocol for a Motor Execution Task

A common paradigm for investigating motor system function involves simple motor acts. The following workflow outlines a typical experiment.

Figure 2: A generalized experimental workflow for a motor execution study, common to all neuroimaging modalities.

Step 1: Participant Preparation

- EEG/ECoG: Secure the electrode cap or subdural grid on the participant's head. For EEG, apply conductive gel to lower impedance. For ECoG, this is done during a surgical procedure [12].

- fNIRS: Position optodes on the scalp over the region of interest (e.g., primary motor cortex) using a head cap, ensuring good skin contact [12] [13].

- Intracortical: This involves the surgical implantation of a microelectrode array (e.g., Utah Array) into the target brain area, typically under general anesthesia [10].

Step 2: Baseline Recording A 2-5 minute resting-state recording is conducted where the participant remains relaxed with eyes open or closed. This baseline is used to contrast against task-induced activity [12].

Step 3: Task Execution & Data Acquisition The participant performs a blocked or event-related paradigm. For example:

- Cue (2s): A visual or auditory cue instructs the participant to prepare.

- Execution (3-5s): The participant repeatedly grasps and moves an object [12].

- Rest (10-15s): The participant remains still, allowing neural/hemodynamic activity to return to baseline. This sequence is repeated for multiple trials (e.g., 30-40 trials). For ECoG and intracortical recordings, this is often performed with patients undergoing monitoring for epilepsy [10].

Step 4: Data Preprocessing

- EEG/ECoG: Filtering (e.g., 0.5-40 Hz for ERPs, up to 200 Hz for higher frequencies), artifact removal (e.g., ocular, muscle), and re-referencing [14] [11].

- fNIRS: Converting raw light intensity to optical density, then to HbO and HbR concentrations using the Modified Beer-Lambert Law. Motion artifact correction is applied [9] [11].

- Intracortical: Filtering spikes (300-5000 Hz) and LFPs (0.1-300 Hz) separately. Spike sorting to isolate single-unit activity [10].

Step 5: Data Analysis & Interpretation

- EEG/ECoG: Time-frequency analysis (e.g., Event-Related Spectral Perturbation) to quantify power changes in specific frequency bands (e.g., mu/beta desynchronization during movement) [12].

- fNIRS: General Linear Modeling (GLM) is used to compare HbO/HbR concentrations during the task blocks against the rest blocks, generating statistical parametric maps of activation [9].

- Intracortical: Analyzing firing rates of individual neurons or LFP power in relation to movement kinematics (e.g., direction, force) [10].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents and Materials

Successful experimentation relies on specialized hardware and software. The following table details essential components for a multimodal setup.

Table 2: Essential materials and reagents for neural signal acquisition experiments.

| Item Name | Function/Description | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Integrated EEG-fNIRS Cap | An elastic cap with pre-defined openings and fixtures to hold both EEG electrodes and fNIRS optodes, ensuring co-registration of modalities [14] [12]. | Simultaneously recording electrical and hemodynamic activity during a cognitive-motor task [12]. |

| Conductive Electrode Gel | A gel or paste applied to EEG electrodes to facilitate electrical contact between the scalp and the electrode, reducing impedance. | Essential for obtaining high-quality, low-noise EEG signals. |

| Microelectrode Array (e.g., Utah Array) | A grid of fine, sharp electrodes designed for intracortical implantation to record single-unit activity and LFPs [10]. | Investigating neural tuning properties in primary motor cortex for brain-computer interface control [10]. |

| Subdural Grid/Strip Electrodes | A flexible array of disc electrodes embedded in a silicone sheet, implanted under the dura mater for ECoG recording [10]. | Pre-surgical mapping of eloquent cortical areas (e.g., motor, language) in epilepsy patients. |

| Synchronization Hardware/Software | A system (e.g., TTL pulse generators, shared clock software) to precisely align data streams from different acquisition devices [14]. | Mandatory for temporal alignment of EEG and fNIRS data in a multimodal experiment. |

| Structured Sparse Multiset CCA (ssmCCA) | A data fusion algorithm used to identify correlated components across multimodal datasets (e.g., EEG and fNIRS) [12]. | Pinpointing brain regions where electrical and hemodynamic activity are jointly modulated by a task [12]. |

EEG, fNIRS, ECoG, and intracortical signals each provide a unique window into brain function, with inherent trade-offs defined by their origin and acquisition method. Non-invasive techniques (EEG, fNIRS) offer accessible and safe platforms for basic research and clinical monitoring in more naturalistic settings, with EEG leading in temporal resolution and fNIRS in spatial specificity for surface cortex. Invasive techniques (ECoG, Intracortical), while carrying surgical risks, provide unparalleled signal quality and specificity, enabling advanced brain-computer interfaces and detailed investigation of neural coding. The future of neural interface research lies not only in refining these individual technologies but also in their strategic integration. Multimodal approaches, such as combined EEG-fNIRS, are increasingly demonstrating that the synergistic use of complementary signals can overcome the limitations of any single modality, offering a more holistic and powerful tool for understanding the brain and developing novel clinical interventions.

Brain-Computer Interfaces (BCIs) represent a transformative technology that establishes a direct communication pathway between the brain and external devices [15]. These systems can be broadly categorized into invasive interfaces, which require surgical implantation of electrodes directly into brain tissue, and non-invasive interfaces, which measure brain activity from the scalp surface [4]. The performance and application potential of these neural interfaces are fundamentally governed by three core technical parameters: spatial resolution, temporal resolution, and signal-to-noise ratio (SNR).

Spatial resolution refers to the ability to distinguish neural activity from distinct brain regions, temporal resolution indicates how precisely neural activity can be tracked over time, and SNR represents the clarity of the neural signal against background noise [2] [16]. These three parameters form a critical trade-off triangle that dictates the capabilities and limitations of both invasive and non-invasive BCIs, influencing their suitability for research applications, clinical interventions, and consumer products.

This comparative analysis examines these fundamental trade-offs through the lens of current research and technological capabilities, providing researchers and drug development professionals with a structured framework for evaluating neural interface technologies.

Technical Comparison of Invasive vs. Non-Invasive Neural Interfaces

Table 1: Fundamental Performance Characteristics of Neural Interface Technologies

| Interface Type | Spatial Resolution | Temporal Resolution | Signal-to-Noise Ratio | Primary Signal Sources |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Invasive (Intracortical) | Single neuron level (μm) [16] | Millisecond (kHz range) [16] | Very High [17] | Action potentials, local field potentials [16] |

| Minimally Invasive (ECoG) | ~1 mm (electrode spacing) [2] | Millisecond [2] | High [2] | Cortical surface potentials [2] |

| Non-Invasive (EEG) | ~1-3 cm [16] | Millisecond (but limited to <90 Hz) [16] | Low (attenuated by skull) [16] | Scalp potentials from pyramidal neurons [16] |

| Non-Invasive (fNIRS) | ~1 cm [4] | Seconds (hemodynamic response) [4] | Low to Moderate [4] | Hemodynamic changes [4] |

| Non-Invasive (MEG) | ~5 mm [4] | Millisecond [4] | Moderate (requires shielding) [4] | Magnetic fields from neural currents [4] |

Table 2: Information Transfer Capabilities and Applications

| Interface Type | Theoretical Information Transfer Rate | Medical Applications | Research Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Invasive | High (dozens of bits/min demonstrated) [16] | Paralysis, severe motor impairments [4] [17] | Motor control, speech decoding [2] |

| Non-Invasive | Low to Moderate (highly variable) [18] | Neurorehabilitation, basic assistive tech [2] [19] | Cognitive neuroscience, brain mapping [2] |

The performance disparities between invasive and non-invasive approaches stem from fundamental biophysical principles. Invasive electrodes directly access neural electrical activity, bypassing the signal-degrading effects of the skull and other tissues [16]. In contrast, non-invasive techniques like EEG measure attenuated signals that have passed through multiple biological layers, resulting in significantly reduced spatial resolution and SNR [16]. As one analysis notes, "The signals obtained through the scalp are often weaker and more susceptible to noise, which can affect the precision of device control" [17].

Temporal characteristics also differ substantially. While both EEG and invasive methods offer millisecond-level temporal resolution, non-invasive systems face inherent bandwidth limitations. As one researcher observes, "with the exception of AP bursts in neuronal populations, non-invasive signals mainly allow analysis of low-frequency neuronal activity (<≈90 Hz)" [16]. This high-frequency limitation restricts the types of neural phenomena accessible to non-invasive monitoring.

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Invasive BCI Motor Control Paradigm

Objective: To enable real-time control of external devices using motor intention signals decoded from intracortical recordings [2].

Methodology:

- Surgical Implantation: Utah array or similar multi-electrode arrays are implanted in motor cortical regions (e.g., primary motor cortex, posterior parietal cortex) [2] [16].

- Signal Acquisition: Neural activity (action potentials and local field potentials) is recorded from hundreds to thousands of neurons [2].

- Feature Extraction: Movement parameters (direction, velocity, grip force) are decoded from neural firing patterns using algorithms like Kalman filters or neural networks [2].

- Closed-Loop Control: Decoded movement commands are translated to robotic arm or computer cursor control in real-time, with visual feedback provided to the user [16].

- Adaptive Learning: Both the user and the decoding algorithm adapt through practice, with users learning to modulate neural activity and algorithms improving decoding accuracy [16].

Key Metrics: Task completion accuracy, information transfer rate, time to target acquisition [16].

Non-Invasive EEG-Based Motor Imagery

Objective: To control external devices through imagined movements without physical execution [15].

Methodology:

- Electrode Placement: EEG electrodes are positioned over sensorimotor cortex regions according to the International 10-20 system [18].

- Paradigm Design: Users imagine specific motor acts (e.g., hand grasping, foot movement) without physical movement [15].

- Signal Processing: Event-related desynchronization/synchronization (ERD/ERS) of mu (8-12 Hz) and beta (13-30 Hz) rhythms are extracted as control features [15].

- Classification: Machine learning algorithms (e.g., common spatial patterns, linear discriminant analysis) distinguish between different motor imagery states [15].

- Feedback: Real-time visual or tactile feedback is provided to facilitate user learning and system control [15].

Key Metrics: Classification accuracy, information transfer rate, false positive rate [18].

Emerging Protocol: Temporal Interference Stimulation

Objective: To achieve non-invasive deep brain stimulation for potential therapeutic applications [20].

Methodology:

- Electrode Configuration: Multiple electrode pairs are placed on the scalp to create interfering electric fields [20].

- Field Generation: Two high-frequency (kHz) electric fields with slight frequency difference (Δf) are applied, creating an amplitude-modulated envelope at the difference frequency [20].

- Focal Targeting: The interference pattern is steered to deep brain structures (e.g., hippocampus) by adjusting current ratios between electrode pairs [20].

- Validation: Electric field modeling and cadaver measurements verify focal stimulation of target structures [20].

- Physiological Assessment: Functional MRI and behavioral tests confirm target engagement and functional modulation [20].

Key Metrics: Envelope modulation amplitude, stimulation focality, behavioral effects [20].

Diagram 1: Signal Pathway Comparison (46 characters)

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Research Materials for Neural Interface Development

| Item | Function | Example Applications |

|---|---|---|

| Utah Array | Multi-electrode cortical implant for high-density neural recording [2] | Invasive motor BMI research [2] |

| Dry EEG Electrodes | Scalp electrodes that don't require conductive gel [4] | Consumer BCI, portable neuroimaging [4] |

| WIMAGINE Device | Implantable ECoG grid system for chronic recording [2] | Restorative neuroprosthetics [2] |

| Stentrode | Endovascular electrode deployed via blood vessels [2] | Minimally invasive motor BCI [2] |

| fNIRS Systems | Functional near-infrared spectroscopy for hemodynamic monitoring [4] | Brain activity monitoring in natural environments [4] |

| Digital Holographic Imaging | Non-invasive, high-resolution neural activity recording [21] | Novel signal detection through tissue deformation [21] |

| Temporal Interference Stimulation | Non-invasive deep brain stimulation [20] | Targeted neuromodulation without surgery [20] |

The fundamental trade-offs between spatial resolution, temporal resolution, and signal-to-noise ratio present researchers with critical choices when selecting neural interface methodologies. Invasive approaches provide superior signal quality and information transfer rates essential for complex control tasks, but require surgical intervention and carry associated medical risks [16] [17]. Non-invasive technologies offer safety, accessibility, and whole-brain coverage, but face inherent biophysical limitations that constrain their performance for precision applications [16].

Future directions in neural interface research focus on overcoming these trade-offs through technological innovation. Emerging approaches include minimally invasive techniques like the Stentrode [2], novel signal detection methods such as digital holographic imaging [21], and advanced stimulation paradigms like temporal interference [20]. The continued evolution of these technologies promises to expand both fundamental neuroscience research and clinical applications, potentially narrowing the performance gap between invasive and non-invasive approaches while mitigating their respective limitations.

The Historical Trajectory and Key Milestones in NI Development

Neural Interfaces (NIs) represent a revolutionary technology that enables direct communication between the human brain and external devices. This field has evolved along two primary trajectories: invasive approaches that require surgical implantation of electrodes into or onto brain tissue, and non-invasive approaches that record neural signals from outside the skull. The historical development of NIs has been characterized by continuous trade-offs between signal fidelity and accessibility, with invasive methods providing higher spatial and temporal resolution at the cost of surgical risk and limited participant pools, while non-invasive approaches offer greater safety and accessibility but with compromised signal quality [2]. This comparative analysis examines the key milestones, performance metrics, and experimental protocols that have defined the evolution of both invasive and non-invasive neural interfaces, providing researchers with a comprehensive framework for evaluating current technologies and guiding future development.

The fundamental dichotomy in NI approaches stems from the challenge of measuring minute electrical signals generated by neural activity through various biological barriers. Invasive technologies such as intracortical electrodes and electrocorticography (ECoG) provide direct access to neural signals but face challenges related to long-term stability, biocompatibility, and limited clinical translation due to their invasive nature [2]. Non-invasive technologies including electroencephalography (EEG), functional near-infrared spectroscopy (fNIRS), and magnetoencephalography (MEG) circumvent surgical risks but must contend with signal attenuation caused by the skull and other tissues [22]. Recent advancements in signal processing, machine learning, and sensor technology have progressively narrowed the performance gap between these approaches, enabling unprecedented applications in both clinical and recreational domains [23] [2].

Historical Trajectory and Technological Evolution

Key Milestones in Neural Interface Development

The development of neural interfaces follows a distinct historical pathway characterized by foundational discoveries, technological innovations, and paradigm-shifting applications. The trajectory began with the discovery of electrical activity in the brain and the development of EEG in the early 20th century, which established the foundation for non-invasive brain monitoring [22]. The 1950s-1970s saw the first direct recordings from animal and human neurons, paving the way for invasive approaches. The formal conceptualization of Brain-Computer Interfaces (BCIs) in the 1970s marked a critical milestone, establishing the framework for direct brain-to-device communication [2].

The 1990s-2000s witnessed significant advancement in invasive technologies, particularly with the development of the Utah Array and other multi-electrode systems that enabled stable recordings from hundreds of individual neurons [22]. This period also saw the first successful demonstrations of invasive BCIs for cursor control in humans. Concurrently, non-invasive technologies benefited from the integration of advanced signal processing techniques and the development of more portable, affordable EEG systems [2]. The 2010s marked the emergence of commercial non-invasive BCIs for gaming and wellness applications, while invasive approaches demonstrated increasingly complex control of robotic prosthetics and communication devices for paralyzed individuals [22] [23].

Recent developments (2020-2025) have been characterized by several transformative trends. Miniaturization and wireless connectivity have enabled more practical form factors for both invasive and non-invasive systems [6]. The application of deep learning and neural networks has dramatically improved decoding accuracy across all modalities [2]. Hybrid approaches that combine multiple signal acquisition methods have emerged to overcome limitations of individual technologies [23]. Particularly noteworthy is the recent development of a generic non-invasive neuromotor interface based on surface electromyography (sEMG) that demonstrates unprecedented cross-participant generalization while achieving high-bandwidth communication previously only possible with invasive interfaces [6].

Comparative Technological Analysis

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Major Neural Interface Technologies

| Technology | Spatial Resolution | Temporal Resolution | Invasiveness | Primary Applications | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intracortical Electrodes | Single neuron (~50-100μm) | Milliseconds (∼1kHz) | High (surgical implantation required) | Robotic arm control, speech decoding [2] | Limited long-term stability, tissue response [2] |

| ECoG | Local field potentials (~1mm) | Milliseconds (∼1kHz) | Medium (requires craniotomy) | Motor restoration, epilepsy monitoring [2] | Limited cortical coverage, lower spatial resolution than intracortical [2] |

| sEMG | Muscle group level (~5-10mm) | Milliseconds (∼2kHz) | Non-invasive | Handwriting transcription, gesture recognition [6] | Limited to motor commands, anatomical variability [6] |

| EEG | ~1-10cm | ~10-100 milliseconds | Non-invasive | Basic communication, gaming, rehabilitation [2] | Low signal-to-noise ratio, limited spatial resolution [2] |

| fNIRS | ~1-2cm | Seconds | Non-invasive | Brain state monitoring, neurofeedback | Low temporal resolution, indirect hemodynamic measure [22] |

| fUS | ~100μm | Seconds (~2-10Hz) | Minimally invasive (requires cranial window) | Motor intention decoding [2] | Low temporal resolution, requires surgical access [2] |

Table 2: Performance Benchmarks Across Neural Interface Types (2020-2025)

| Interface Type | Information Transfer Rate (bits/min) | Decoding Accuracy (%) | Typical Applications | Representative Performance |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Invasive (Intracortical) | 100-500 | 90-99 | Speech decoding, robotic control | Speech decoding at 62-78 words/minute [2] |

| Invasive (ECoG) | 50-200 | 85-95 | Motor restoration, spelling | Walking restoration in paralyzed patients [2] |

| Non-invasive (sEMG) | 80-180 | 90-95 | Handwriting, gesture control | 20.9 words per minute handwriting [6] |

| Non-invasive (EEG) | 5-60 | 70-90 | Basic control, neurofeedback | 0.66 target acquisitions/sec in continuous navigation [6] |

| Non-invasive (fNIRS) | 5-20 | 65-80 | Brain state monitoring | Classification of motor imagery [22] |

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Protocol for Non-invasive sEMG-based Neuromotor Interface

Recent groundbreaking research has demonstrated a non-invasive surface electromyography (sEMG) interface that achieves performance metrics previously only associated with invasive systems [6]. The experimental methodology encompasses several meticulously designed components:

Hardware Configuration: The research team developed a custom dry-electrode, multichannel sEMG recording device (sEMG-RD) with a high sample rate (2 kHz) and low-noise characteristics (2.46 μVrms) [6]. The device was fabricated in four different sizes (10.6, 12, 13, or 15 mm circumferential interelectrode spacing) to accommodate anatomical variation, approaching the spatial bandwidth of EMG signals at the forearm (~5-10 mm) while minimizing form factor. A strategic gap in electrode placement allowed for tightening adjustments along the ulna bone where muscle density is reduced, enabling sensing of putative motor unit action potentials (MUAPs) during low-movement conditions.

Participant Recruitment and Data Collection: The study employed an unprecedented scale of participant recruitment, encompassing 162-6,627 participants across different tasks, selected to represent anthropometric and demographic diversity [6]. Participants wore sEMG bands on their dominant-side wrist and performed three distinct tasks: (1) wrist control, where participants controlled a cursor with position determined from wrist angles tracked via motion capture; (2) discrete-gesture detection involving nine distinct gestures performed in randomized order with variable intergesture intervals; and (3) handwriting, where participants held their fingers together as if holding a writing implement and "wrote" prompted text. A real-time processing engine recorded both sEMG activity and label timestamps while a custom time-alignment algorithm addressed variations in participant reaction time and compliance.

Signal Processing and Decoding Architecture: The researchers developed neural networks trained on the large-scale dataset to transform sEMG signals into commands for computer interactions [6]. The models were designed to generalize across participants without individual calibration, addressing a fundamental challenge in BCI systems. The architecture incorporated techniques to minimize online-offline shift and handle the substantial variability in sEMG patterns across participants and sessions resulting from differences in sensor placement, anatomy, physiology, and behavior.

Protocol for Invasive Intracortical Speech Decoding

Invasive approaches have demonstrated remarkable capabilities in decoding neural signals for communication applications. The experimental methodology for state-of-the-art speech decoding involves:

Surgical Implantation: Participants with severe paralysis undergo surgical implantation of high-density microelectrode arrays (such as the Utah Array) into regions of the motor cortex associated with speech production [2]. These arrays typically contain hundreds of microelectrodes that record single-unit and multi-unit activity with high temporal resolution (~30 kHz sampling rate). The implantation procedure requires precise stereotactic positioning based on pre-operative imaging and functional mapping.

Neural Signal Acquisition: Raw neural signals are amplified, filtered, and processed to extract features relevant to speech production [2]. The processing pipeline typically includes: (1) bandpass filtering to separate local field potentials (LFP) from spike activity; (2) spike detection and sorting to identify action potentials from individual neurons; and (3) feature extraction that may include firing rates, population vectors, or spectral power in specific frequency bands. The system requires physically wired connections between the brain implant and external decoding hardware, creating challenges for long-term use and portability.

Decoding Algorithm Training: Participants are asked to attempt to speak or imagine speaking words and sentences while neural activity is recorded [2]. The corresponding audio or textual representations serve as training labels for supervised learning algorithms. Recent approaches have utilized recurrent neural networks (RNNs) and long short-term memory (LSTM) networks that model temporal dependencies in speech production. The trained models learn to map patterns of neural activity to intended speech sounds, words, or directly to text.

Performance Validation: Decoding performance is evaluated using metrics such as word error rate, characters per minute, or information transfer rate [2]. State-of-the-art systems have achieved decoding rates of 62-78 words per minute with vocabularies of hundreds of thousands of words, approaching natural conversation speeds.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Essential Research Materials for Neural Interface Development

| Item | Function | Example Specifications | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| High-Density Microelectrode Arrays | Record neural activity at single-neuron resolution | 64-256 channels, 50-100μm electrode spacing, 1-4kHz sampling rate | Invasive intracortical recording for motor control and speech decoding [2] |

| Dry sEMG Electrodes | Record muscle electrical activity without conductive gels | 2kHz sampling, 2.46μVrms noise, multiple sizes for anatomical variation | Non-invasive gesture recognition and handwriting transcription [6] |

| ECoG Grids | Record from brain surface with higher resolution than EEG | 16-256 contacts, 1cm spacing, subdural placement | Motor restoration, epilepsy monitoring [2] |

| Neural Signal Amplifiers | Amplify microvolt-level neural signals | High input impedance, programmable gain, built-in filters | Essential for all recording modalities to amplify weak neural signals [2] |

| Data Acquisition Systems | Convert analog signals to digital format | 16-24 bit resolution, simultaneous sampling, USB or wireless interface | NI data acquisition systems set standards for accuracy and performance [24] |

| Biocompatible Encapsulants | Protect implanted electronics from body fluids | Parylene-C, silicone elastomers, ceramic packages | Long-term stability of invasive neural interfaces [22] |

| Open-Source BCI Toolboxes | Signal processing and machine learning pipelines | MATLAB, Python, or Julia-based with real-time capabilities | Accelerate algorithm development and standardization [2] |

Comparative Analysis and Future Trajectories

Performance Benchmarking Across Modalities

The comparative analysis of invasive versus non-invasive neural interfaces reveals distinct performance characteristics and application domains. Invasive approaches consistently demonstrate superior information transfer rates, with intracortical interfaces achieving speeds necessary for fluent speech decoding and dexterous robotic control [2]. These systems provide access to neural signals at the spatial and temporal resolution required for decoding complex motor commands and cognitive processes. However, this performance comes with significant limitations: restricted participant pools due to surgical risks, challenges with long-term signal stability, and substantial technical support requirements.

Non-invasive approaches have historically offered substantially lower bandwidth but greater accessibility [2]. Recent advancements, particularly in sEMG-based interfaces, have dramatically narrowed this performance gap. The demonstrated capability of non-invasive sEMG to achieve 20.9 words per minute for handwriting transcription and 0.88 gesture detections per second approaches the functional utility of some invasive systems while maintaining complete non-invasiveness [6]. This represents a significant milestone in NI development, suggesting that strategic focus on signal acquisition and processing innovations can yield substantial performance improvements without surgical intervention.

The trade-offs between these approaches are further illustrated by their generalization capabilities. Invasive systems typically require extensive per-participant calibration and show limited generalization across users due to individual neuroanatomical differences and precise electrode placement [6] [2]. In contrast, recent non-invasive approaches have demonstrated remarkable cross-participant generalization, with models trained on thousands of participants performing effectively for new users without individual calibration [6]. This scalability advantage represents a critical consideration for widespread implementation.

Emerging Trends and Future Development Trajectories

The historical trajectory of NI development suggests several convergent trends that will shape future research directions. Hybrid approaches that combine multiple signal acquisition modalities are increasingly demonstrating complementary advantages [23]. Systems that simultaneously record EEG and fNIRS, or combine sEMG with inertial measurement units (IMUs), overcome limitations of individual technologies while preserving non-invasiveness.

Advanced materials science is driving innovations in both invasive and non-invasive interfaces [22]. For invasive systems, development of more biocompatible electrodes with reduced foreign body response and improved long-term stability is a critical research frontier. For non-invasive systems, materials innovations focus on higher conductivity dry electrodes, comfortable wearables, and systems that maintain signal quality during movement.

Machine learning and signal processing advancements continue to enhance performance across all modalities [6] [2]. Transfer learning approaches that leverage data from multiple participants to improve performance for new users are particularly promising for addressing the generalization challenge. Personalization techniques that efficiently adapt generic models to individual users with minimal calibration data represent another important direction.

The commercialization and standardization of NI technologies is accelerating translation from research to application [23]. Increasing availability of open-source toolboxes, standardized performance metrics, and regulatory frameworks for clinical applications is creating an ecosystem conducive to rapid innovation. The projected growth of the BCI market from $2.41 billion in 2025 to $12.11 billion by 2035 reflects increasing investment and commercial interest in both invasive and non-invasive technologies [23].

The historical trajectory of neural interface development reveals a field in rapid transition, with traditional trade-offs between invasiveness and performance being redefined by technological innovations. Invasive approaches continue to set benchmarks for signal fidelity and decoding performance, particularly for complex applications like speech decoding and dexterous robotic control. Meanwhile, non-invasive approaches are achieving unprecedented levels of performance and cross-participant generalization, dramatically expanding potential user populations and application domains.

The comparative analysis presented in this guide provides researchers with a framework for selecting appropriate technologies based on specific application requirements, participant populations, and performance targets. As the field continues to evolve, the convergence of materials science, signal processing, and machine learning promises to further narrow the performance gap between invasive and non-invasive approaches while addressing persistent challenges related to scalability, accessibility, and long-term reliability. These advancements will undoubtedly unlock new possibilities for human-computer interaction, neurorehabilitation, and fundamental neuroscience research in the coming decade.

Methodologies, Real-World Applications, and Current Market Landscape

Brain-Computer Interfaces (BCIs) represent a revolutionary technology that enables direct communication between the human brain and external devices [25]. Unlike their invasive counterparts, which require surgical implantation, non-invasive BCIs measure brain activity from the scalp, offering a safer and more accessible alternative for a wide range of applications [17]. The global non-invasive BCI market is projected to capture a majority share of the overall BCI market, which is forecast to grow from USD 2.41 billion in 2025 to USD 12.11 billion by 2035 [25]. This growth is largely driven by the wide applicability of non-invasive technologies in healthcare, consumer wellness, and assistive technology, bolstered by their user-friendliness and lower risk profile [4] [25]. This guide provides a comparative analysis of the dominant non-invasive applications, detailing their performance, underlying experimental protocols, and the essential tools required for research and development.

Performance Comparison of Dominant Non-Invasive BCI Applications

The performance of non-invasive BCIs varies significantly across different application domains, primarily due to the distinct neural signals and decoding challenges inherent to each use case. The table below summarizes the key performance metrics and technological focuses for the three dominant applications.

Table 1: Performance Metrics and Technological Focus of Dominant Non-Invasive BCI Applications

| Application Domain | Primary Signal & Modality | Key Performance Metrics | Typical Information Transfer Rate (ITR) | Primary Technological Focus |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Neurodiagnostics & Medical Monitoring | Spontaneous EEG/ERPs [2] | Sensitivity, Specificity, Spatial Resolution | Not Primary Focus | High-density scalp EEG systems for diagnosis of epilepsy, sleep disorders, and traumatic brain injury [4] [2] |

| Consumer Wellness & Neurofeedback | Oscillatory EEG (Alpha, Beta bands) [4] | Usability, Comfort, Long-term Stability | Low | Wearable EEG headsets for sleep monitoring, emotional state tracking, and meditation [4] [26] |

| Basic BCI & Assistive Technology | Sensorimotor Rhythms, SSVEP, P300 [2] | Classification Accuracy, Speed, Reliability | Medium | EEG-based systems for communication (e.g., text spelling) and control (e.g., wheelchair navigation) for individuals with paralysis [2] [27] |

Experimental Protocols & Methodologies

Robust experimental protocols are fundamental to the development and validation of non-invasive BCI technologies. The following section outlines standard methodologies employed across the dominant application domains.

Protocol for Motor Imagery-Based BCI Control

This protocol is typical for developing assistive technologies, such as controlling a computer cursor or a robotic arm [2].

- Participant Preparation & Setup: The participant is fitted with a multi-channel EEG cap, typically following the international 10-20 system. Electrode impedances are checked and reduced to below 10 kΩ to ensure high-quality signal acquisition. The participant is seated in a comfortable chair in a dimly lit, shielded room to minimize environmental artifacts [2].

- Signal Acquisition & Hardware: Neural signals are recorded using a high-density EEG system (e.g., 64-128 channels) with a sampling rate of at least 250 Hz. The hardware includes amplifiers and analog-to-digital converters to capture microvolt-level brain signals [2].

- Paradigm & Task: The participant performs a series of cued motor imagery tasks, such as imagining left-hand or right-hand movement without any physical execution. Each trial begins with a fixation cross, followed by a visual cue indicating the specific task, and an imagery period of several seconds [2].

- Data Processing & Decoding:

- Pre-processing: Acquired EEG signals are filtered (e.g., 8-30 Hz bandpass for sensorimotor rhythms) and artifacts from eye movements or muscle activity are removed using algorithms like Independent Component Analysis (ICA) [2].

- Feature Extraction: Features are extracted from the EEG signals, commonly focusing on changes in band power (e.g., Event-Related Desynchronization in the mu/beta rhythms over the sensorimotor cortex) [2].

- Classification: A machine learning classifier (e.g., Support Vector Machine or Linear Discriminant Analysis) is trained on the extracted features to discriminate between the different motor imagery states. This model is then used for real-time control [2].

- Output & Feedback: The decoder's output is translated into a command for an external device. The system provides real-time visual feedback to the participant, for instance, by moving a cursor on a screen, creating a closed-loop system that enables the user to learn and improve control [2].

Protocol for Neurodiagnostic Monitoring (e.g., Epilepsy)

This protocol is standard for clinical diagnosis and monitoring of neurological conditions like epilepsy.

- Patient Setup: The patient is fitted with a full-cap EEG electrode system in a clinical setting. The setup is like the research protocol but often with a strong emphasis on consistent electrode placement for longitudinal comparisons [4].

- Signal Acquisition: Long-term, continuous EEG is recorded, often over 24-48 hours, in an inpatient setting or at home with portable devices. The recording captures both resting-state activity and activity during potential seizure events [4].

- Data Analysis & Detection: The recorded data is analyzed, either by a trained clinician or automated software, to identify pathological patterns such as spikes, sharp waves, or seizure discharges. The analysis focuses on signal morphology and temporal patterns rather than intentional control signals [4].

The experimental workflow for a standard non-invasive BCI protocol, from participant setup to closed-loop feedback, is visualized below.

Signaling Pathways & Neural Correlates

The efficacy of non-invasive BCIs hinges on detecting specific neural signals that reflect user intention, cognitive state, or pathological activity.

Primary Neural Signals in Non-Invasive BCI

- Sensorimotor Rhythms (SMR): These are oscillatory patterns in the mu (8-12 Hz) and beta (13-30 Hz) frequency bands recorded over the sensorimotor cortex. During motor imagery or movement preparation, these rhythms exhibit Event-Related Desynchronization (ERD)—a decrease in power. Upon movement cessation, they show Event-Related Synchronization (ERS)—an increase in power. This predictable modulation is the cornerstone for motor-based BCIs [2].

- Event-Related Potentials (ERPs): ERPs are voltage fluctuations in the EEG signal that are time-locked to a specific sensory, cognitive, or motor event. The P300 potential, a positive deflection occurring about 300 ms after an infrequent target stimulus, is widely used in BCI spellers. The P300's amplitude is inversely related to stimulus probability, making it a robust marker for attention-based selection [2].

- Steady-State Visually Evoked Potentials (SSVEP): When a user gazes at a visual stimulus flickering at a fixed frequency, the visual cortex generates an oscillatory EEG response at the same frequency (and its harmonics). By detecting which frequency is present in the EEG, a BCI can determine which stimulus the user is attending to, enabling high-ITR communication systems [2].

- Pathological Patterns: In neurodiagnostics, the focus is on aberrant signals. For epilepsy, this includes interictal epileptiform discharges (spikes and sharp waves) and ictal rhythms (seizure activity characterized by rhythmic patterns that evolve in frequency and amplitude) [4].

The diagram below illustrates the relationship between external events, the resulting neural signals measured by EEG, and their characteristics.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Advancing non-invasive BCI research requires a suite of reliable hardware, software, and analytical tools. The following table details essential components of a modern non-invasive BCI research toolkit.

Table 2: Essential Tools and Reagents for Non-Invasive BCI Research

| Tool/Reagent | Function/Description | Example Vendors/Platforms |

|---|---|---|

| High-Density EEG Systems | Records electrical potential from the scalp with high spatial resolution; the core hardware for signal acquisition. | ANT Neuro, CGX, G.Tec Medical Engineering [25] |

| Dry & Wet Electrodes | Interface with the scalp for signal transduction. Dry electrodes improve usability, while wet electrodes (with gel) offer better signal quality. | Material innovations are a key R&D area [4] |

| Open-Source BCI Software | Provides standardized pipelines for signal processing, feature extraction, and machine learning classification. | OpenBCI, BCILAB, Psychtoolbox [2] |

| Stimulation Hardware | Presents visual, auditory, or tactile stimuli to evoke measurable neural responses (ERPs, SSVEP). | |

| Artifact Removal Algorithms | Software tools to identify and remove non-neural signals from data (e.g., eye blinks, muscle activity). | Independent Component Analysis (ICA) is a standard method [2] |

| Machine Learning Libraries | Enable the development of custom decoders to translate neural features into control commands. | Scikit-learn, TensorFlow, PyTorch (as applied to neural data) [2] |

Non-invasive BCIs have carved out critical and distinct application niches in neurodiagnostics, consumer wellness, and basic assistive communication. Their dominance is secured by their safety profile, accessibility, and the maturity of supporting technologies like high-density EEG and advanced machine learning. While invasive interfaces may offer superior signal resolution for complex motor control, non-invasive technologies are unmatched for applications where risk, cost, and large-scale deployment are primary concerns. Future progress will likely stem from advancements in signal processing, dry electrode technology, and the integration of artificial intelligence, further solidifying the role of non-invasive BCIs in both clinical and consumer markets.

Invasive neural interfaces represent a cutting-edge frontier in neurotechnology, offering direct access to neural signals by placing electrodes within the skull—either on the brain's surface (epidural or subdural) or within brain tissue itself (intracortical). These technologies have evolved beyond experimental concepts into clinically validated solutions for severe neurological disorders, particularly for patients with motor disabilities who have exhausted conventional treatment options. The fundamental rationale for pursuing invasive approaches lies in their superior signal quality compared to non-invasive alternatives; intracortical electrodes and electrocorticography (ECoG) provide higher spatial resolution, broader bandwidth, and improved signal-to-noise ratio, enabling more precise decoding of neural intent for controlling external devices or modulating pathological neural circuits [4] [19].

The clinical landscape for these interfaces is rapidly evolving, with the overall brain-computer interface market forecast to grow to over $1.6 billion by 2045 [4]. This growth is propelled by advances in materials science, neural decoding algorithms, and minimally invasive surgical techniques. Invasive interfaces are primarily deployed for three principal applications: motor neuroprosthetics for restoring movement and communication, deep brain stimulation (DBS) for modulating dysfunctional neural circuits, and functional restoration for severe paralysis conditions. This comparative analysis examines the current state of these technologies, their relative performance metrics, and the experimental protocols validating their clinical efficacy, providing researchers and clinicians with a framework for evaluating their therapeutic potential.

Technology Comparison: Performance Metrics and Clinical Applications

Performance Benchmarking of Invasive Neural Interfaces

Table 1: Comparative Performance Metrics of Invasive Neural Interfaces

| Interface Type | Spatial Resolution | Temporal Resolution | Signal-to-Noise Ratio | Primary Clinical Applications | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intracortical Microelectrodes | Very High (micron-scale) | Very High (milliseconds) | High | Motor control for paralysis, neural decoding for communication | Tissue response, signal stability over time |

| Electrocorticography (ECoG) | High (mm-scale) | High (milliseconds) | Moderate-High | Epilepsy monitoring, motor neuroprosthetics | Limited penetration depth, requires craniotomy |

| Deep Brain Stimulation (DBS) Electrodes | Medium (cm-scale) | Therapeutic stimulation | N/A | Parkinson's disease, essential tremor, dystonia | Invasive implantation, side effects from stimulation |

Invasive interfaces demonstrate distinct performance characteristics that determine their clinical applications. Intracortical microelectrodes, such as the Utah Array used by Blackrock Neurotech, provide the highest spatial and temporal resolution, enabling detailed decoding of movement intentions from individual neurons or small neural populations [4] [28]. This high-fidelity signal is essential for complex tasks such controlling robotic arms or enabling typing through neural signals. However, these interfaces face challenges with long-term signal stability due to the brain's tissue response to implanted microelectrodes [28].

Electrocorticography (ECoG) approaches offer a balance between signal quality and invasiveness. By placing electrodes on the surface of the brain (below the dura mater), ECoG systems capture neural population signals with higher spatial resolution and signal-to-noise ratio compared to non-invasive electroencephalography (EEG), while avoiding some of the long-term stability issues associated with intracortical implants [28] [19]. A fully implanted ECoG system demonstrated reliable decoding of movement-intent with approximately 90% accuracy in a subject with cervical quadriplegia, enabling volitional control of hand grasp both in laboratory and home environments [28].

Deep brain stimulation (DBS) electrodes represent a different class of invasive interfaces focused on therapeutic modulation rather than signal recording. These systems deliver electrical stimulation to specific deep brain structures to modulate pathological neural activity. DBS has received FDA approval for essential tremor (1997), Parkinson's disease (2002), and dystonia (2003), establishing it as the most clinically validated invasive neuromodulation approach [19].

Clinical Application Comparison

Table 2: Clinical Applications and Efficacy Metrics

| Application | Technology Implementations | Key Efficacy Metrics | Representative Clinical Outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Severe Paralysis Restoration | Intracortical BMI, ECoG with FES | Decoding accuracy, Functional independence measures | 89-91% decoding accuracy for hand grasp [28]; Improved object transfer tasks |

| Parkinson's Disease Symptoms | Deep Brain Stimulation (DBS) | Tremor reduction, Medication reduction | Significant tremor suppression; Reduced levodopa requirements [29] [19] |

| Communication Restoration | Intracortical speech decoding | Characters per minute, Accuracy | Real-time decoding with >90% accuracy for 8-word vocabulary [19] |

| Spinal Cord Injury Rehabilitation | Epidural SCS with rehabilitation | Walking ability, Voluntary movement recovery | Independent overground walking with continuous SCS [29] |

For severe paralysis conditions, particularly cervical spinal cord injury, invasive brain-computer interfaces have demonstrated remarkable capabilities. In one landmark study, a fully implanted ECoG system allowed a participant with complete cervical quadriplegia to achieve volitional control of hand grasp with 89.0% accuracy in laboratory settings and 88.3% accuracy during closed-loop trials at home [28]. This performance remained stable throughout the 29-week laboratory study and subsequent home use, highlighting the potential for long-term functional restoration.

Deep brain stimulation has established itself as a transformative therapy for movement disorders, with well-documented efficacy in large patient populations. Unlike motor neuroprosthetics that primarily decode and execute motor commands, DBS works by modulating pathological neural circuits. For Parkinson's disease, high-frequency stimulation of the subthalamic nucleus or internal globus pallidus effectively suppresses tremors, rigidity, and bradykinesia, significantly improving quality of life and reducing medication requirements [29] [19].

Recent advances have also explored the application of invasive interfaces for cognitive disorders, though this represents a more nascent field. Preliminary studies suggest that electrical neuromodulation strategies might potentially alleviate some cognitive and memory deficits, particularly in the context of dementia, though the neural mechanisms underlying cognition are considerably more complex than those for sensorimotor functions [29].

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Implantable BCI for Hand Grasp Restoration

A comprehensive study published in 2021 detailed the methodology for restoring volitional control of hand grasp in a 21-year-old male with complete cervical quadriplegia (C5 ASIA Impairment Scale A) using a fully implanted brain-computer interface [28]. The experimental protocol encompassed several distinct phases:

Screening and Participant Selection: Twenty-one subjects with C5/C6 motor complete SCI underwent EEG-based screening to test their ability to trigger a functional electrical stimulation (FES) device through motor imagery of dominant hand movement versus rest states. Only one subject qualified for surgical implantation after completing 16 sessions of EEG screening, demonstrating the importance of careful participant selection [28].

Surgical Implantation Protocol: Pre-operative functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) mapped cortical activation during imagined dominant hand movements and actual shoulder movements. Diffusion tensor imaging identified the location of corticospinal tract fibers previously controlling dominant hand movement. These merged images guided a small craniotomy over the left motor cortex using frameless stereotaxy. Intraoperative electrical stimulation and electromyogram (EMG) monitoring definitively identified motor cortex by evoking EMG activity in proximal muscles [28].

System Configuration and Signal Processing: The implanted system consisted of subdural surface electrodes placed over the dominant-hand motor cortex connected to a transmitter implanted subcutaneously below the clavicle, enabling continuous reading of electrocorticographic (ECoG) activity. Movement-intent was decoded from the ECoG signals to trigger functional electrical stimulation of the dominant hand during laboratory studies and subsequently control a mechanical hand orthosis during in-home use [28].

Assessment Metrics: The study employed multiple quantitative measures including decoding accuracy for movement intent, performance on upper extremity tasks (lifting small objects, transferring objects to specific targets), and temporal stability of functional outcomes. Laboratory decoding accuracy averaged 89.0% (range 78-93.3%), while at-home decoding reached 91.3% (range 80-98.95%) during open-loop trials and 88.3% (range 77.6-95.5%) during closed-loop trials [28].

Figure 1: Experimental workflow for fully implanted BCI deployment

Spinal Cord Stimulation for Locomotor Recovery

Multiple research groups have developed protocols for spinal cord stimulation (SCS) to restore motor function after spinal cord injury, employing distinct methodological approaches:

Conventional Continuous SCS: The Kentucky SCI Center implemented continuous SCS combined with intensive rehabilitation in participants with motor-complete SCI. Training included standing, body-weight-supported treadmill stepping, and overground walking, all with continuous SCS delivered via fully implanted leads in the posterior epidural space connected to an implantable pulse generator [29].

Spatiotemporal SCS: Courtine and Bloch's team developed a paradigm using real-time control capabilities to alternate stimulation between swing, weight acceptance, and propulsion phases of the gait cycle. Electrode configurations were triggered either at a pre-defined pace or in real-time by residual kinematic events. This approach was tested in nine participants with chronic incomplete SCI, including three with motor-complete SCI implanted with electrode arrays tailored for both leg and trunk motor functions [29].

Assessment Metrics: Studies measured the recovery of voluntary leg movements with and without stimulation, quantitative gait analysis, and functional independence measures. Notably, participants demonstrated significant improvement in assisted standing, trunk stability, and overground walking ability with assistive devices after extended training periods ranging from 15 to 85 weeks [29].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Essential Research Materials for Invasive Neural Interface Studies

| Item Category | Specific Examples | Research Function | Implementation Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Electrode Technologies | Utah Array (Blackrock), Neuropixels, Custom ECoG grids | Neural signal acquisition | Intracortical arrays for single-unit recording; ECoG for population signals |

| Signal Acquisition Systems | Wireless transmitters, Implantable pulse generators | Signal transmission and power delivery | Subclavian implantation for cosmesis and reduced infection risk [28] |

| Stimulation Apparatus | Functional electrical stimulators, DBS pulse generators | Therapeutic neuromodulation | Multi-channel systems for targeted muscle activation or deep brain stimulation |

| Neural Decoding Algorithms | Support vector machines, Deep learning networks | Movement intent classification | Real-time processing of ECoG or spike signals for device control |

| Surgical Navigation | Pre-operative fMRI, DTI, Frameless stereotaxy | Precision electrode placement | Motor cortex localization for optimal signal acquisition [28] |

| Assessment Tools | Upper extremity task batteries, Gait analysis systems | Functional outcome measurement | Standardized metrics for decoding accuracy and clinical improvement |

The development and implementation of invasive neural interfaces requires specialized materials and instrumentation. Electrode technologies form the foundation, with intracortical microelectrode arrays providing the highest signal resolution but potentially facing long-term stability challenges, while ECoG electrodes offer a balance between signal quality and reduced tissue trauma [4] [28].

Signal acquisition systems have evolved toward fully implanted wireless platforms that enable continuous recording and processing outside laboratory environments. These systems include subcutaneous transmitters that communicate with external receivers, allowing participants to use the technology in home settings without direct clinical supervision [28].

Neural decoding algorithms represent the computational core of motor neuroprosthetics, translating raw neural signals into control commands for external devices. These typically employ machine learning approaches trained on individual participant data to classify movement intent with accuracies typically exceeding 85-90% in optimized systems [28].

Assessment methodologies include both performance metrics (decoding accuracy, speed of task completion) and functional outcome measures specific to the target clinical application. For motor restoration, these may include standardized upper extremity task batteries, while for locomotor recovery, quantitative gait analysis and independence measures are employed [29] [28].

Figure 2: Neural signal processing pathway for invasive BCIs

Comparative Analysis: Invasive versus Non-Invasive Approaches

The selection between invasive and non-invasive neural interfaces involves careful consideration of risk-benefit ratios, signal fidelity requirements, and target applications. Invasive technologies provide substantial advantages in signal quality, with ECoG and intracortical systems offering higher spatial resolution, temporal resolution, and signal-to-noise ratios compared to non-invasive alternatives like EEG [4]. This enhanced signal fidelity translates to superior performance in complex control tasks, higher information transfer rates, and reduced training requirements.

However, these advantages must be balanced against the surgical risks, potential for tissue response, and higher costs associated with invasive approaches [4]. Non-invasive systems, while limited in signal quality, offer safety and accessibility advantages that make them suitable for a broader range of applications, particularly in consumer neurotechnology and preliminary clinical assessment [19].

The evolving neurotechnology landscape suggests a future with multiple coexisting modalities tailored to specific clinical needs. Invasive interfaces will likely remain the gold standard for severe paralysis conditions requiring high-fidelity control, while non-invasive approaches may dominate in diagnostic, monitoring, and consumer applications. Future directions include the development of minimally invasive approaches, such as endovascular electrodes that can be delivered through blood vessels, potentially offering an intermediate solution with improved signal quality over non-invasive systems while reducing surgical risks [19].

The field of neural interfaces has long been defined by a fundamental trade-off: the pursuit of high-fidelity neural signals has necessitated invasive technologies that carry significant surgical risks and biological challenges. Invasive brain-computer interfaces (BCIs), such as the Utah Array, penetrate brain tissue to record from individual neurons but can trigger inflammatory responses and scar tissue formation, which degrade signal quality over time [27]. On the opposite end of the spectrum, completely non-invasive techniques like electroencephalography (EEG) offer safety and accessibility but are limited by poor spatial resolution and signal strength due to the damping effect of the skull and scalp [2].

Against this backdrop, minimally invasive technologies have emerged as a promising middle path. This guide provides a comparative analysis of two leading approaches: Stentrodes, which are endovascular electrodes, and functional ultrasound (fUS), which images neural activity through acoustic signals. Both aim to circumvent the skull barrier without penetrating delicate brain parenchyma, potentially offering superior signal quality compared to non-invasive methods while avoiding the key pitfalls of fully invasive implants. Their development represents a pivotal direction in neurotechnology, seeking to balance signal fidelity, procedural risk, and long-term stability for both research and clinical applications.

Technology Comparison: Stentrodes vs. Functional Ultrasound

The following table provides a direct, data-driven comparison of Stentrode and functional ultrasound technologies across critical technical and application parameters.

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Stentrode and Functional Ultrasound Neural Interfaces

| Feature | Stentrode | Functional Ultrasound (fUS) |

|---|---|---|