Individual Differences in Addiction Neurobiology: From Genetic Risk to Personalized Treatment

This article synthesizes current research on the neurobiological basis of individual differences in addiction vulnerability, progression, and treatment response.

Individual Differences in Addiction Neurobiology: From Genetic Risk to Personalized Treatment

Abstract

This article synthesizes current research on the neurobiological basis of individual differences in addiction vulnerability, progression, and treatment response. Targeting researchers and drug development professionals, it explores the foundational genetic, developmental, and neural circuit mechanisms that create divergent pathways to addiction. The scope extends to methodological innovations in imaging and genetics, troubleshooting challenges in disease modeling and theoretical integration, and validating findings through comparative analysis of competing frameworks. The review emphasizes a consilience approach, arguing that integrating neuroscientific, behavioral, and clinical perspectives is crucial for advancing personalized addiction medicine.

The Biological Underpinnings of Addiction Vulnerability: Genetics, Circuits, and Early Risk

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. What is the heritable component of addiction risk? Family and twin studies indicate that genetic factors contribute to approximately 40-60% of the risk for developing a substance use disorder. The specific heritability varies by substance [1] [2].

2. Are there genetic factors shared across different substance use disorders? Yes, multivariate genetic analyses reveal both shared and substance-specific genetic influences. For example, a cross-ancestry multivariate GWAS identified a shared genetic factor among alcohol, cannabis, opioid, and tobacco use disorders, while also highlighting specific loci like CHRNA2 that are more specific to cannabis use disorder [3] [4].

3. How do anxiety disorders and problematic alcohol use interact genetically? Recent genomic studies show a substantial genetic overlap and a bidirectional causal relationship between problematic alcohol use (PAU) and anxiety disorders (ANX). They share a significant number of genetic variants, many of which have concordant (same direction) effects on both conditions [5].

4. What are the primary molecular pathways implicated in addiction? Research has identified several key pathways, including dopaminergic signaling, cAMP signaling, long-term potentiation, MAPK signaling, and GnRH signaling. These are involved in synaptic plasticity, reward, and reinforcement [5] [2].

5. In which brain regions are addiction-related genes most active? Gene expression analyses show enrichment in brain regions critical for reward, decision-making, and emotion, including the prefrontal cortex, anterior cingulate cortex, hippocampus, hypothalamus, substantia nigra, and amygdala [5].

Quantitative Data on Heritability and Genetic Correlations

Table 1: Heritability Estimates and Key Genetic Findings for Substance Use Disorders

| Substance Use Disorder | Heritability (Twin/Family Studies) | SNP-based Heritability (h²snp) | Key Replicated Risk Genes / Loci |

|---|---|---|---|

| Problematic Alcohol Use (PAU) | ~50% [3] | 5.6% - 10.0% [3] | ADH1B, ADH1C, ADH4, ADH5, ADH7, DRD2 [3] |

| Cannabis Use Disorder (CUD) | ~50-60% [3] | Information Missing | CHRNA2, FOXP2 [3] |

| Tobacco Use Disorder (TUD) | ~30-70% [3] | Information Missing | CHRNA5-CHRNA3-CHRNB4, DNMT3B, MAGI2/GNAI1, TENM2 [3] |

| Opioid Use Disorder (OUD) | Information Missing | Information Missing | Information Missing |

Table 2: Genetic Correlations Between Problematic Alcohol Use and Comorbid Traits

| Trait | Genetic Correlation (rg) with Problematic Alcohol Use | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Anxiety Disorders (ANX) | rg = 0.44 [5] | High effect direction concordance (86.4%) among shared variants [5]. |

| Other Substance Use Disorders | Strong positive correlations [4] | Strongest with opioid use disorder, cannabis use disorder, and problematic alcohol use [4]. |

| Psychiatric Traits | Strong positive correlations [4] | Notably with suicidality [4]. |

Experimental Protocols & Methodologies

Protocol 1: Mendelian Randomization to Test Causal Relationships

Objective: To assess whether a putative risk factor (e.g., anxiety) has a causal effect on an outcome (e.g., problematic alcohol use), or vice versa, using genetic variants as instrumental variables.

Workflow:

- Instrument Selection: Identify genetic variants (SNPs) that are strongly and reliably associated with the exposure trait (e.g., anxiety) from a large GWAS.

- Effect Size Extraction: Extract the association effects of these same genetic instruments on the outcome trait (e.g., problematic alcohol use) from an independent GWAS.

- Causal Estimation: Perform a two-sample Mendelian Randomization analysis (e.g., using inverse-variance weighted method) to estimate the causal effect of the exposure on the outcome [5].

- Bidirectional Analysis: Repeat steps 1-3, swapping the exposure and outcome to test for reverse causality [5].

- Sensitivity Analyses: Conduct pleiotropy-robust methods (e.g., MR-Egger, MR-PRESSO) to validate that results are not biased by horizontal pleiotropy.

Protocol 2: Conjunctional FDR for Identifying Shared Genetic Loci

Objective: To pinpoint specific genetic loci that are shared between two related traits (e.g., PAU and ANX) while increasing discovery power.

Workflow:

- Input Summary Statistics: Use GWAS summary statistics (p-values and effect directions) for both traits.

- ConjFDR Analysis: Apply the conjunctional false discovery rate (conjFDR) framework. This method identifies SNPs associated with either trait, then tests whether they are also associated with the other trait, conditioning on the first association.

- Identify Shared Loci: Declare a SNP as a shared locus if its conjFDR value falls below a specified significance threshold (e.g., < 0.05).

- Annotate and Map: Annotate the identified lead SNPs to genes and examine their effect direction (concordant or discordant) on both traits [5].

Table 3: Essential Resources for Investigating the Genetics of Addiction

| Resource / Reagent | Function / Application | Example / Source |

|---|---|---|

| GWAS Summary Statistics | Foundation for genetic correlation, MR, and polygenic score analyses. | Million Veteran Program (MVP), UK Biobank (UKB), Psychiatric Genomics Consortium (PGC) [3]. |

| Knowledgebase of Addiction-Related Genes (KARG) | A curated database of human addiction-related genes with extensive functional annotations. | http://karg.cbi.pku.edu.cn [2] |

| FUMA (FUctional Mapping and Annotation) | An online platform for the functional annotation of GWAS results, including gene mapping, tissue expression, and cell-type specificity analyses. | Used in recent studies to map SNPs to genes and conduct expression analyses [5]. |

| Mendelian Randomization Software | Statistical packages to perform MR analysis and sensitivity checks. | TwoSampleMR (R package), MR-Base. |

| Key Candidate Genes | Targets for functional validation experiments (e.g., in animal or cell models). | DRD2 (dopamine signaling), PDE4B (cAMP signaling), ADH1B (alcohol metabolism), CHRNA2 (cholinergic signaling) [5] [3]. |

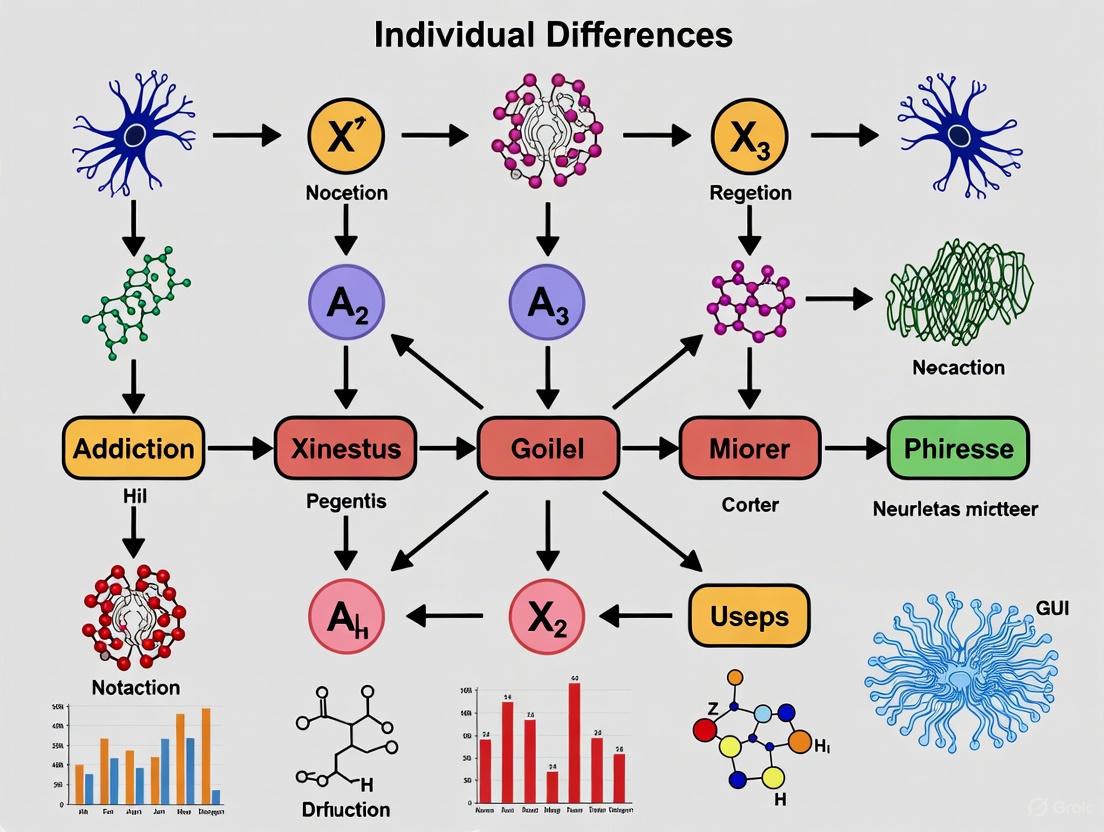

Visualization of Key Shared Molecular Pathways

The integration of genetic findings has highlighted several key molecular pathways that are shared across multiple substance use disorders and their comorbidities. The following diagram synthesizes these pathways into a core network, centered on dopamine signaling and its downstream effects on synaptic plasticity.

Core Concepts: The Neurobiological Basis of Sex-Specific Risk

Q: What is the central finding regarding sex-specific neural trajectories in youth with a family history of substance use disorder (SUD)?

A: A large-scale 2025 study analyzing nearly 1,900 children from the Adolescent Brain Cognitive Development (ABCD) Study found that a family history of SUD is associated with early, sex-divergent differences in brain activity dynamics, long before any substance use begins [6] [7]. The key finding is that girls and boys show opposing patterns of "transition energy"—a measure of the brain's effort to shift between different activity states—in distinct neural networks [6].

Q: What are the specific neural patterns observed in at-risk girls versus boys?

A: The patterns are opposing, as summarized in the table below [6] [7]:

| Sex | Neural Signature | Brain Network Affected | Proposed Behavioral Correlate |

|---|---|---|---|

| Females | Increased Transition Energy | Default-Mode Network (DMN) | Greater difficulty disengaging from internal states like stress or rumination; substance use may later serve as a way to escape [6]. |

| Males | Decreased Transition Energy | Dorsal and Ventral Attention Networks | Heightened reactivity to the environment and sensation-seeking; a tendency toward unrestrained behavior [6]. |

Q: How do these findings fit into the broader thesis of individual differences in addiction neurobiology?

A: This research underscores that sex is a critical biological variable shaping individual vulnerability to addiction. It demonstrates that the same familial risk factor can manifest as distinct neurobiological pathways in males and females [6]. This challenges homogeneous models of addiction and emphasizes the need for personalized prevention strategies that target these specific risk profiles—for instance, focusing on stress coping in girls and impulse control in boys [6] [7].

Experimental Protocols & Methodologies

Q: What was the primary experimental dataset and population used in this research?

A: The study analyzed data from the Adolescent Brain Cognitive Development (ABCD) Study, a large longitudinal NIH study in the United States [6]. The cohort included nearly 1,900 children aged 9 to 11 years, ensuring the observed differences predate substance use initiation [6] [7].

Q: What is the core methodology for quantifying brain activity dynamics?

A: The primary computational approach used is Network Control Theory (NCT) applied to resting-state functional MRI (fMRI) data [6].

- Protocol: When a subject lies in an MRI scanner at rest, the brain cycles through recurring patterns of activation. NCT calculates the "transition energy" required for the brain to shift between these different activity patterns [6].

- Measurement: This "transition energy" serves as a metric for the brain's flexibility or inertia. Higher energy implies less flexibility and more effort required to change states, while lower energy suggests greater ease of transition and potentially less cognitive control [6].

Q: Why is the analysis of sex-specific data critical in this protocol?

A: The researchers found that averaging data across both sexes masked the contrasting neural patterns. Conducting separate analyses for boys and girls was essential to reveal the opposing effects of family history on transition energy in attention versus default-mode networks [6]. This is a crucial methodological consideration for all research on individual differences.

Experimental Workflow Diagram

Troubleshooting & Experimental Replication

Q: What could lead to a failure to detect these sex-specific effects?

A: The most common error would be pooling data from males and females without stratification for the primary analysis. The study's authors explicitly note that these divergent patterns were only visible when data from boys and girls were analyzed separately [6]. Always include sex as a key biological variable in your experimental design and statistical models.

Q: How should "family history of SUD" be reliably defined and collected in a research setting?

A: The ABCD Study and other large cohorts typically use standardized, validated instruments such as structured interviews or detailed family history questionnaires. Best practices include:

- Using clear diagnostic criteria (e.g., based on DSM-5) to define SUD in family members.

- Gathering information on the degree of relation (first-degree vs. second-degree relatives).

- Employing multiple informants where possible to improve accuracy.

Q: Our analysis shows inconsistent results with the transition energy metric. What are potential sources of variance?

A: Inconsistencies can arise from several factors:

- Data Quality: Ensure high-quality fMRI pre-processing to minimize motion artifacts, a significant concern in pediatric populations.

- Parcellation Scheme: The definition of brain networks (like the DMN or Attention Networks) can vary. Test the robustness of your findings across different brain atlases.

- Computational Implementation: Verify the implementation of the NCT model, including the parameters used for defining brain states and calculating energy.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

The following table details key resources and their functions for research in this domain.

| Research Tool / Reagent | Function & Application in Context |

|---|---|

| ABCD Study Dataset | A foundational, openly available resource providing longitudinal neuroimaging, genetic, behavioral, and environmental data from a large pediatric cohort, ideal for studying developmental trajectories [6]. |

| Network Control Theory (NCT) | A computational framework applied to fMRI data to model brain network dynamics and quantify the energy required for transitions between neural states [6]. |

| Resting-state fMRI | A non-invasive imaging technique that measures spontaneous brain activity to map functional connectivity networks without a task, crucial for studying intrinsic brain organization [6]. |

| Structured Clinical Interviews | Validated instruments (e.g., based on DSM-5 criteria) for consistently assessing substance use disorder in probands and their family members to define "family history" [6]. |

Neurobiological Pathways to Addiction

The sex-specific early vulnerabilities interact with the established three-stage cycle of addiction, which involves disruptions in three key brain regions [8] [9]. The following diagram integrates the early vulnerabilities with this broader framework.

Addiction Vulnerability Pathway

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What specific neurodevelopmental processes during adolescence increase vulnerability to substance use initiation? Adolescence is characterized by a mismatch in the development of subcortical limbic systems and the prefrontal cortex. Key processes include:

- Synaptic Pruning and Myelination: The brain undergoes significant refinement, reducing gray matter volume in prefrontal and temporal cortices while increasing white matter integrity through myelination, which improves neural conductivity [10]. Higher-order association areas mature only after lower-order sensorimotor regions, with frontal lobes being the last to complete development [10].

- Imbalanced Development: Subcortical limbic systems, which process rewards and emotions, mature earlier than the prefrontal cortex, which is responsible for executive control, impulse inhibition, and long-term planning [11] [10]. This imbalance creates a period of heightened reward sensitivity, novelty-seeking, and risk-taking, behaviors that can directly lead to substance use initiation [11].

Q2: How do individual differences in brain structure predict subsequent substance use? Pre-existing structural differences can serve as biomarkers for substance use vulnerability. Key predictors include:

- Prefrontal Cortex Volume: Smaller prefrontal cortex volumes, particularly in females, have been observed prior to or in conjunction with the onset of heavy drinking [10].

- Brain Maturation Patterns: Variations in the typical trajectories of cortical thinning and gray matter volume reduction may be associated with a predisposition to substance use [11]. Research is actively characterizing these individual differences to understand their role in the transition from use to dependence [12].

Q3: What are the most critical neuroimaging modalities for investigating the adolescent brain in the context of substance use? The primary non-invasive modalities used in human adolescents are:

- Structural MRI (sMRI): Used to investigate gross brain morphology, including cortical thickness, and gray and white matter volumes. For example, studies have linked adolescent alcohol use to smaller frontal cortices and hippocampal volumes [11] [13] [10].

- Functional MRI (fMRI): Infers brain region activity by measuring dynamic cerebral blood flow (BOLD signal). It is used to study reward processing, cue reactivity, and executive control in adolescent substance users [11].

- Diffusion Tensor Imaging (DTI): Investigates white matter microstructure by measuring water diffusivity across axon bundles, providing an index of neural connectivity and integrity [11].

Q4: What is the neurobiological mechanism underlying the transition from recreational use to addiction? The progression to addiction is conceptualized as a chronic, relapsing cycle with three core stages, each linked to specific neuroadaptations [8] [14]:

- Binge/Intoxication: Focused on the basal ganglia. Dopamine release reinforces drug use, and repeated use leads to "incentive salience," where cues associated with the drug trigger powerful motivational urges [8] [14].

- Withdrawal/Negative Affect: Centered on the extended amygdala (the "anti-reward" system). Chronic use leads to a downregulation of reward systems and an upregulation of brain stress systems (e.g., CRF, dynorphin), resulting in anxiety, irritability, and dysphoria when not using the drug [8] [14].

- Preoccupation/Anticipation: Governed by the prefrontal cortex. This stage is marked by executive dysfunction, including reduced impulse control and emotional regulation, and intense cravings, which drive the relapse cycle [8] [14].

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Challenges

Challenge 1: Accounting for Pre-Existing Vulnerabilities vs. Substance-Induced Effects

- Problem: It is methodologically difficult to determine whether observed neural differences in adolescent substance users are a consequence of drug exposure or a pre-existing risk factor.

- Solution:

- Implement Longitudinal Designs: The gold-standard approach is to recruit substance-naïve adolescents and perform repeated neuroimaging and neuropsychological assessments before and after substance use initiation [13]. The landmark ABCD Study is a prime example of this methodology [15].

- Careful Participant Screening: Rigorously match user and non-user groups on potential confounding variables such as family history of substance use disorders, prenatal exposure, conduct disorder symptoms, and other psychopathologies [10].

- Statistical Control: Use variables like age of first use, frequency, and quantity of use as covariates in analyses to help disentangle dose-dependent effects from predisposing traits [13].

Challenge 2: Controlling for Polysubstance Use

- Problem: Adolescents rarely use a single substance in isolation, making it challenging to attribute neurobiological findings to a specific drug.

- Solution:

- Stringent Inclusion Criteria: Recruit participants with well-characterized primary substance use patterns and minimal use of other drugs. This may reduce generalizability but improves interpretability.

- Statistical Modeling: Treat polysubstance use as a quantitative covariate or use data-driven approaches (e.g., factor analysis) to model the effects of multiple substances [13] [16].

- Targeted Recruitment: Focus on emerging trends, such as e-cigarette use (for nicotine and/or cannabis), and clearly define the primary substance of interest [11].

Challenge 3: Ensuring Valid and Reliable Neurocognitive Assessment

- Problem: Subtle neurocognitive deficits in adolescent users can be masked by generally high cognitive reserve or confounded by motivation, practice effects, or subclinical withdrawal.

- Solution:

- Abstinence Verification: For studies of current users, verify recent abstinence (e.g., 24-48 hours) using breathalyzer and urine toxicology screens to minimize acute intoxication or withdrawal effects [10].

- Battery Design: Use comprehensive, standardized neuropsychological batteries that assess multiple domains known to be affected, such as verbal and spatial memory, attention, speeded information processing, and executive functioning [10].

- Alternative Measures: Incorporate laboratory-based behavioral tasks (e.g., delay discounting, stop-signal task) that provide precise metrics of impulsivity and decision-making, which are core constructs in addiction [12].

Key Neuroimaging Findings in Adolescent Substance Use

Table 1: Long-term Neurostructural Correlates of Adolescent-Initiated Substance Use

| Substance | Key Structural Findings | Associated Cognitive/Behavioral Correlates |

|---|---|---|

| Alcohol | Smaller frontal cortex volumes; reduced gray matter volume decline over time; smaller left hippocampal volume [13] [10]. | Deficits in memory, attention, speeded information processing, and executive functioning; spatial functioning impairments linked to withdrawal history [10]. |

| Cannabis | Altered frontal cortex volumes; mixed findings on hippocampal volume (smaller with more years since initiation) [13]. | Poorer performance on learning, cognitive flexibility, visual scanning, and working memory; number of lifetime use episodes predicts poorer overall functioning [10]. |

| Tobacco/Nicotine | Smaller frontal cortices (especially OFC); altered white matter microstructure [13]. | Worsened attentional performance; symptoms of inattention; deficits in selective and divided attention [11]. |

| Stimulants | Trend towards altered volumes in putamen, insula, and frontal cortex [13]. | (Data less consolidated; often involves polysubstance use) |

| Opioids | Smaller subcortical and insular volumes [13]. | (Data less consolidated) |

Table 2: Core Neurobiological Stages of Addiction Relevant to Adolescent Development

| Stage of Addiction Cycle | Core Brain Region | Primary Neuroadaptations | Behavioral Manifestation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Binge/Intoxication | Basal Ganglia | Dopamine release & incentive salience; shift from goal-directed to habitual control (ventral to dorsal striatum) [8] [14]. | Positive reinforcement; drug-seeking for rewarding effects. |

| Withdrawal/Negative Affect | Extended Amygdala | Recruitment of brain stress systems (CRF, dynorphin); reduced reward system function [8] [14]. | Negative emotional state (anxiety, irritability); negative reinforcement. |

| Preoccupation/Anticipation | Prefrontal Cortex | Executive dysfunction; decreased inhibitory control; heightened craving [8] [14]. | Compulsivity; loss of control over drug use; cravings. |

Experimental Protocols & Workflows

Protocol 1: Longitudinal sMRI Analysis of Cortical Development

- Objective: To determine if adolescent substance use alters the normative trajectory of cortical brain development.

- Procedure:

- Acquisition: Collect high-resolution T1-weighted MRI scans at baseline (pre-initiation) and at regular follow-up intervals (e.g., annually).

- Preprocessing: Process images using standardized software (e.g., Freesurfer, SPM) for cortical reconstruction and volumetric segmentation. Key steps include noise correction, skull stripping, and tissue classification into gray/white matter.

- Analysis:

- Extract cortical thickness and surface area for regions of interest (e.g., prefrontal cortex, insula) and globally.

- Use mixed-effects modeling to compare the longitudinal trajectories of cortical measures between substance-use groups and matched controls, controlling for age, sex, and intracranial volume.

- Relate changes in brain structure to changes in substance use patterns (e.g., escalation) and neurocognitive performance over time.

Protocol 2: fMRI Task-Based Analysis of Reward Processing

- Objective: To assess neural responses to drug cues and monetary rewards in adolescent substance users.

- Procedure:

- Task Design: Implement a validated fMRI paradigm, such as a Monetary Incentive Delay (MID) task and a separate drug cue-reactivity task.

- Acquisition: Acquire T2*-weighted BOLD images during task performance. Monitor for head motion.

- Preprocessing: Use pipelines like fMRIPrep or SPM. Steps include realignment, slice-time correction, normalization to standard space, and smoothing.

- First-Level Analysis: Model the BOLD response for different task conditions (e.g., drug cue vs. neutral cue; reward anticipation vs. outcome) for each participant.

- Second-Level Analysis: Compare contrast images (e.g., [Drug Cue > Neutral Cue]) between user and control groups using a whole-brain or ROI-based approach (e.g., in the ventral striatum, OFC). Correlate neural activity with craving measures.

Signaling Pathways & Neurocircuitry

The following diagram illustrates the key neurocircuits and neurotransmitter systems involved in the three-stage addiction cycle, highlighting targets for adolescent vulnerability.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials and Methods for Adolescent Addiction Neuroscience

| Research Tool | Function/Application | Specific Examples/Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Structural MRI Analysis Software | Quantifies brain volume, cortical thickness, and surface area from T1-weighted images. | FreeSurfer, FSL, SPM. Critical for tracking developmental trajectories and group differences [13] [10]. |

| fMRI Analysis Pipelines | Processes BOLD data to model brain activity during cognitive tasks or at rest. | fMRIPrep, SPM, FSL, AFNI. Essential for investigating reward, cue reactivity, and executive control [11]. |

| Diffusion Tensor Imaging (DTI) | Models white matter microstructure and structural connectivity (e.g., fractional anisotropy). | FSL's FDT toolbox, Tournier's MRtrix3. Used to assess the integrity of developing white matter tracts [11] [10]. |

| Standardized Neuropsychological Batteries | Assesses cognitive domains known to be impacted by substance use (memory, attention, executive function). | NIH Toolbox, Wechsler scales, and specific tasks for delay discounting (impulsivity) and stop-signal task (response inhibition) [12] [10]. |

| Animal Models of Adolescent Intermittent Access | Allows for controlled investigation of causal effects of adolescent drug exposure on adult outcomes. | Intermittent ethanol vapor or voluntary consumption (e.g., two-bottle choice) in rodents; allows for examination of molecular mechanisms (e.g., epigenetic changes) [16]. |

FAQs: Core Concepts and Common Experimental Challenges

Q1: What are the core neurocircuits and primary functions of the three-stage addiction cycle?

The addiction cycle is a framework for understanding the persistent neurobiological changes that drive compulsive substance use. It is characterized by three recurring stages, each mediated by distinct brain circuits and neurotransmitter systems [8] [14].

Binge/Intoxication Stage: This stage is dominated by the basal ganglia and its circuits. The initial pleasurable effects of a substance are linked to increased dopaminergic and opioid peptide release in the nucleus accumbens (NAcc) within the ventral striatum, a key part of the mesolimbic pathway [8] [14]. As use continues, a shift occurs from "liking" the substance to "wanting" it, a process known as incentive salience. Dopamine firing begins to respond more to substance-associated cues (people, places, things) than the substance itself, fueling reward-seeking behavior. The nigrostriatal pathway, involving the dorsolateral striatum, becomes increasingly involved in controlling these habitual behavior [8].

Withdrawal/Negative Affect Stage: This stage is primarily governed by the extended amygdala (including the bed nucleus of the stria terminalis and central nucleus of the amygdala), often termed the brain's "anti-reward" system [8] [14]. Chronic substance use leads to a downregulation of the brain's reward systems (e.g., decreased dopaminergic tone in the NAcc) and a recruitment of brain stress systems. This results in the increased release of stress mediators like corticotropin-releasing factor (CRF), dynorphin, and norepinephrine [8]. The clinical presentation includes irritability, anxiety, dysphoria, and a diminished capacity to feel pleasure from natural rewards, which creates a powerful negative reinforcement to resume substance use.

Preoccupation/Anticipation Stage: This stage, which occurs during abstinence, is marked by "cravings" and a loss of executive control, primarily mediated by the prefrontal cortex (PFC) [8]. Executive functions such as planning, emotional regulation, and impulse control are compromised. The PFC can be conceptualized as having a "Go system" (for goal-directed behaviors) and a "Stop system" (for inhibitory control); in addiction, this balance is disrupted, leading to executive dysfunction and powerful preoccupation with obtaining the substance [8] [14].

Q2: How does motivation shift from positive to negative reinforcement during the progression of addiction?

The progression from recreational use to addiction involves a critical transition in the primary motivation for substance use [14].

Early Stage: Positive Reinforcement. Initial use is typically driven by positive reinforcement. The substance produces a pleasurable "high" or euphoria (the a-process), which makes the individual more likely to use it again. Behavior at this stage is often impulsive, undertaken for the immediate pleasure with little regard for future consequences [8] [14].

Later Stage: Negative Reinforcement. With repeated use, the pleasurable effects diminish due to tolerance, while the opposing, negative b-process (withdrawal/negative affect) strengthens and appears earlier. Substance use then becomes driven by negative reinforcement—the need to alleviate the distressing symptoms of withdrawal and the underlying negative emotional state. The behavior shifts from impulsive to compulsive, characterized by perseverative use despite adverse consequences [14].

Q3: What are the key individual differences that influence vulnerability to addiction, and how can they be measured?

Individual differences in the neurobiological systems that process reward, incentive salience, habits, stress, and executive function can explain vulnerability to Substance Use Disorders and the diversity of clinical presentations [14] [17]. Key factors include:

- Genetic Variation: Functional polymorphisms in genes related to dopamine signaling (e.g., DRD2, DAT1) have been linked to individual differences in reward-related activation in the ventral striatum and traits like impulsivity, which can increase vulnerability [17].

- Neurofunctional Domains: The Addictions Neuroclinical Assessment (ANA) is a tool that translates the three neurobiological stages into measurable neurofunctional domains: incentive salience, negative emotionality, and executive dysfunction. Assessing these domains helps in characterizing an individual's specific addiction "biotype" [8].

- Circuit-Level Dysfunction: Research indicates there are at least two dissociable cortico-striatal circuits relevant to addiction. Some individuals may exhibit a weakened dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (dlPFC) pathway associated with poor executive control, while others may have a heightened ventromedial prefrontal cortex (vmPFC) pathway linked to exaggerated incentive valuation and stress sensitivity [18]. Modern techniques like functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) and spectral dynamic causal modeling (spDCM) can be used to measure effective connectivity and identify these circuit-level differences [18].

Experimental Protocols: Targeting the Preoccupation/Anticipation Stage with Neuromodulation

The following is a detailed methodology from a recent clinical trial investigating deep Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation (dTMS) to modulate the dysregulated neurocircuitry of addiction, specifically targeting the preoccupation/anticipation stage [18].

Objective: To examine the capacity of two theta-burst stimulation (TBS) protocols to modify neuroimaging and behavioral indices of alcohol use disorder (AUD)-related neurocircuitry alterations, focusing on executive control and craving.

Background: The preoccupation/anticipation stage is characterized by executive dysfunction mediated by the prefrontal cortex. This protocol specifically targets two key nodes: the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (dlPFC) (part of the "Go system" for executive control) and the ventromedial prefrontal cortex (vmPFC) (part of the limbic circuit for valuation and decision-making) [18].

Protocol Workflow

Detailed Methodology

1. Participant Selection and Eligibility:

- Inclusion: 30 adults (18-49) with current moderate to severe AUD per DSM-5 criteria [18].

- Exclusion: Current or past psychosis, mania, or major unstable psychiatric disorder; history of seizure/epilepsy; brain trauma with loss of consciousness in past 6 months; contraindications for MRI or TMS [18].

2. Trial Design:

- Type: Randomized, single-blind, sham-controlled crossover trial.

- Interventions: Two distinct dTMS protocols using an H-coil for deeper penetration [18]:

- Intermittent TBS (iTBS) to the dlPFC to increase neuronal excitability and strengthen top-down executive control.

- Continuous TBS (cTBS) to the vmPFC to decrease neuronal excitability and dampen hyperactive limbic drive.

- Control: Sham stimulation for placebo comparison.

3. Outcome Measures:

- Primary: Stimulation-induced changes in effective connectivity within targeted dlPFC and vmPFC circuits, measured with resting-state fMRI and spectral dynamic causal modeling (spDCM) [18].

- Secondary: Changes in performance on a cognitive test battery assessing executive control and value-based decision-making.

- Exploratory:

- Laboratory tasks measuring interoceptive processes related to craving.

- Experience Sampling Method (ESM): Daily fluctuations in craving and weekly alcohol consumption tracked for 90 days to assess long-term effects and relapse vulnerability [18].

Data Presentation: Neurotransmitter Systems in the Addiction Cycle

The table below summarizes the key neurotransmitter systems and their roles in the three stages of the addiction cycle, providing a reference for potential pharmacological targets.

Table 1: Key Neurotransmitter Systems and Neuroadaptations in the Addiction Cycle

| Addiction Stage | Primary Brain Region | Key Neurotransmitters/Neuromodulators | Direction of Change & Role |

|---|---|---|---|

| Binge/Intoxication | Basal Ganglia (Ventral Striatum, NAcc) | Dopamine [8] [14] | ↑ Release; mediates incentive salience and reward prediction. |

| Endogenous Opioids (e.g., via μ-opioid receptors) [14] | ↑ Release; contributes to hedonic "high" and reinforcement. | ||

| Endocannabinoids [8] | Modulates dopamine and opioid release. | ||

| Withdrawal/Negative Affect | Extended Amygdala | Corticotropin-Releasing Factor (CRF) [8] | ↑ Release; key driver of stress and anxiety-like responses. |

| Norepinephrine (NE) [8] | ↑ Release; contributes to hyperarousal and stress. | ||

| Dynorphin [8] | ↑ Release; acts on kappa opioid receptors to produce dysphoria. | ||

| Dopamine [8] | ↓ Tonic level in NAcc; leads to anhedonia and reduced motivation for natural rewards. | ||

| Preoccupation/Anticipation | Prefrontal Cortex (PFC) | Glutamate [8] | Imbalance; disrupted signaling underlies executive dysfunction and poor impulse control. |

| GABA [8] | Imbalance; contributes to the shift in excitatory/inhibitory tone in corticostriatal circuits. |

Signaling Pathways and Neurocircuitry

The following diagram illustrates the primary neuroadaptations occurring across the three stages of the addiction cycle, highlighting the within-system and between-system changes that perpetuate the cycle.

Table 2: Essential Research Tools for Investigating the Addiction Neurocircuitry

| Tool/Resource | Category | Primary Function in Research |

|---|---|---|

| Deep TMS (dTMS) with H-coil [18] | Neuromodulation Device | Non-invasive brain stimulation to directly modulate activity and connectivity of deep cortical and subcortical nodes (e.g., dlPFC, vmPFC) in addiction circuits. |

| Functional MRI (fMRI) with Spectral Dynamic Causal Modeling (spDCM) [18] | Neuroimaging & Analysis | Measures task-based and resting-state brain activity. spDCM analyzes the valence (excitatory/inhibitory) and directionality of neural connections within targeted circuits. |

| Experience Sampling Method (ESM) [18] | Behavioral Assessment | Captages real-time, longitudinal data on daily fluctuations in craving, mood, and substance use in a naturalistic setting, reducing recall bias. |

| Theta-Burst Stimulation (TBS) [18] | Neuromodulation Protocol | A patterned TMS protocol (iTBS for potentiation, cTBS for suppression) that mimics endogenous neural firing, offering efficient and potent modulation of cortical excitability. |

| Addictions Neuroclinical Assessment (ANA) [8] | Clinical Framework | A tool to translate the three neurobiological stages of addiction into measurable neurofunctional domains (incentive salience, negative emotionality, executive function) for patient stratification. |

Technical Support Center

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

The following table details key assessment tools and technologies used to investigate trait-based vulnerabilities in addiction neuroscience.

| Item Name | Primary Function/Biological Target | Example Application in Research |

|---|---|---|

| Barratt Impulsiveness Scale (BIS-11) [19] | Assesses trait-level impulsive personality dimensions. | A 30-item self-report questionnaire used to measure attentional, motor, and non-planning impulsivity in study participants. |

| UPPS Impulsive Behavior Scale [19] | Dissects impulsivity into negative/positive urgency, lack of premeditation, lack of perseverance, and sensation seeking. | Used to determine which specific facet of impulsivity is most strongly associated with a substance use disorder (SUD). |

| Stop-Signal Reaction Time (SSRT) Task [19] | Objective measure of response inhibition (motor impulsivity). | Participants must inhibit a prepotent motor response; longer SSRT indicates poorer inhibitory control. |

| Kirby Delay-Discounting Task (KDDT) [19] | Quantifies choice impulsivity by measuring preference for smaller immediate rewards over larger delayed rewards. | A steeper discounting rate is used as a behavioral marker of impulsive decision-making in addiction. |

| Resting-State Electroencephalography (EEG) [20] | Non-invasive measurement of spontaneous brain activity and functional connectivity. | Used to identify neurophysiological correlates of trait impulsivity, such as specific power spectral and network connectivity patterns in the beta band. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: What is the key distinction between "trait" and "state" impulsivity in the context of substance use disorders?

The relationship between impulsivity and Substance Use Disorders (SUDs) is complex and involves three key factors: the trait effect, which is a pre-existing vulnerability characterized by decreased cognitive and response inhibition; the state effect, which refers to acute or chronic changes in brain structure and function caused by substance use; and the influence of genetic and environmental factors like age and sex [19]. Trait impulsivity is a stable, underlying vulnerability marker, whereas state impulsivity is a transient condition influenced by drug intake or withdrawal.

FAQ 2: Our team is observing low correlations between self-report and behavioral measures of impulsivity in our dataset. Is this a methodological problem?

Not necessarily. It is common to find little overlap between self-report questionnaires (e.g., BIS-11) and objective behavioral tasks (e.g., SSRT, delay-discounting) [19]. These tools are understood to measure three conceptually related but quantitatively distinct domains of impulsivity: personality traits, discounting preferences, and response inhibition [19]. It is recommended to use a multi-method assessment battery to capture these different components.

FAQ 3: How does emotional dysregulation specifically contribute to addiction and relapse?

Emotional dysregulation is a core characteristic of substance dependence [21]. It involves disturbances in brain reward and stress systems. This can lead to a bias in emotional processing toward drug-related cues at the expense of natural rewards, enhancing drug craving. Furthermore, chronic drug use can sensitize the brain's stress systems, leading to negative emotional states that persist into abstinence. This negative state motivates drug-taking to achieve relief (negative reinforcement) and significantly increases the risk of relapse [21].

FAQ 4: Which neurophysiological marker from resting-state EEG is most informative for studying impulsivity?

Research indicates that power spectral density and functional connectivity in the beta band are particularly informative. Studies have shown that individuals with gambling addiction exhibit higher beta power, and those with methamphetamine addiction show less efficient network connectivity in this band compared to controls [20]. Furthermore, specific connectivity patterns in the beta band are correlated with impulsivity scores and can help differentiate individuals with addiction from healthy controls [20].

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue 1: Inconsistent or No Significant Findings in Neurophysiological Correlates of Impulsivity

| Potential Cause | Diagnostic Steps | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|

| High Participant Heterogeneity | Check for variations in SUD type, chronicity, and polydrug use history within your cohort. | Implement stricter participant inclusion criteria. Pre-stratify groups based on key clinical variables (e.g., primary drug of abuse, years of use) during the recruitment phase. |

| Comorbid Mental Health Conditions | Administer structured clinical interviews (e.g., SCID-5) to assess for comorbid disorders like ADHD, anxiety, or depression. | Include comorbidities as a separate experimental group or as a covariate in your statistical model to account for their confounding effects on impulsivity measures. |

| Medication Interference | Meticulously document all prescribed medications (e.g., methadone, buprenorphine, naltrexone) that participants may be taking [22]. | Either recruit medication-free participants or ensure that medication status is balanced across groups and included as a statistical covariate in analyses. |

Issue 2: Poor Participant Engagement or High Dropout Rates in Longitudinal Studies

| Potential Cause | Diagnostic Steps | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|

| High Burden of Testing Battery | Audit the total time required for all assessments (clinical, behavioral, neuroimaging). | Streamline the protocol by selecting the most sensitive and specific measures for your primary hypotheses. Consider breaking long sessions into shorter, more manageable visits. |

| Lack of Clinical Support | Assess whether participants feel their broader clinical needs are being met. | Integrate the research study within a treatment program or have clear, streamlined referral pathways to clinical care [22]. This demonstrates a commitment to participant well-being beyond data collection. |

| Insufficient Compensation or Rapport | Solicit anonymous feedback from past participants about their experience. | Implement a fair compensation schedule that increases for follow-up visits. Train research staff extensively on building rapport and communicating with empathy and respect. |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: A Multi-Method Assessment of Impulsivity in Substance Use Disorders

I. Objective To comprehensively profile the different dimensions of impulsivity (trait, behavioral, and neurophysiological) in a cohort of individuals with Substance Use Disorders (SUDs) compared to healthy controls.

II. Materials

- Consent forms and demographic questionnaire

- Clinical Assessments: Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview (MINI) or Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-5 (SCID-5) to confirm SUD and assess comorbidities.

- Self-Report Impulsivity Measures:

- Behavioral Tasks (Computerized):

- Neurophysiological Recording:

- EEG system with a 32-channel (or higher) cap

- Electrically shielded, quiet room

III. Step-by-Step Methodology

- Screening & Consent: Obtain informed consent. Screen participants using clinical interviews to assign them to the SUD or control group based on pre-defined criteria.

- Self-Report Assessment: Administer the BIS-11 and UPPS-P questionnaires in a quiet room, counterbalancing the order of presentation across participants.

- Behavioral Task Setup: Seat the participant approximately 60 cm from the computer monitor. Provide standardized verbal instructions for each task.

- Behavioral Task Execution:

- SSRT Task: Conduct a practice block followed by the main experimental block. The task involves responding to "go" stimuli (e.g., arrows) and inhibiting the response when a "stop" signal (e.g., a tone) occurs shortly after the go stimulus. The stop-signal delay is adjusted dynamically.

- Delay-Discounting Task: Present participants with a series of choices between a smaller, immediate monetary reward and a larger, delayed reward (e.g., "Would you prefer $20 now or $60 in 30 days?").

- EEG Preparation and Recording:

- Prepare the scalp and apply the EEG cap according to the 10-20 system.

- Ensure impedances are kept below 5 kΩ.

- Record a 5-minute resting-state EEG with eyes closed, followed by a 5-minute recording with eyes open, in a seated position.

- Data Analysis:

- Behavioral: Calculate SSRT for the stop-signal task and a discounting parameter (e.g., k-value) for the delay-discounting task.

- Self-Report: Score the questionnaires according to their respective manuals.

- EEG: Preprocess the data (filtering, artifact removal). Compute power spectral density and functional connectivity metrics (e.g., Phase Lag Index) in standard frequency bands, with a focus on beta band activity [20].

Protocol 2: Investigating the Impact of Emotional Cues on Decision-Making

I. Objective To examine how emotional dysregulation biases decision-making processes in individuals with SUDs, using a modified gambling task with emotional stimuli.

II. Materials

- Software: Experiment builder (e.g., E-Prime, PsychoPy) for task programming.

- Stimuli: Standardized emotional images (e.g., from the International Affective Picture System - IAPS) categorized as neutral, positive, and negative.

- Task: A modified version of the Iowa Gambling Task (IGT) [19] where emotional images are presented as context during decision-making blocks.

III. Step-by-Step Methodology

- Participant Grouping: Recruit three groups: SUD group, a psychiatric control group with emotional disorders, and a healthy control group.

- Task Design: The task consists of three blocks, each preceded by a different emotional context (neutral, positive, or negative images). Each block uses the standard IGT structure where participants select cards from four decks with different reward/punishment contingencies.

- Procedure: Participants are seated and instructed to maximize their play money total. They complete the three IGT blocks in a randomized order.

- Data Collection: Record the number of advantageous vs. disadvantageous choices per block, reaction times, and psychophysiological measures (e.g., skin conductance response) if available.

- Data Analysis: Perform a mixed-model ANOVA with Group as a between-subjects factor and Emotional Context (and potentially Task Block) as within-subjects factors on the net score (advantageous - disadvantageous choices). This tests the hypothesis that the SUD group's decision-making is disproportionately impaired under specific emotional contexts, such as heightened risk-taking during positive states (positive urgency) [21].

Experimental Workflow and Signaling Pathways

Research Workflow for Trait Vulnerabilities

Pathways to Addiction Involving Traits

Advanced Methodologies for Deconstructing Heterogeneity: From Neuroimaging to GWAS

Applying Network Control Theory to Measure Brain Flexibility and State Transitions

Network Control Theory (NCT) provides a powerful framework for understanding how the brain's structural connectome informs and constrains its dynamic activity. This technical support guide explores how NCT can be applied to study individual differences in addiction neurobiology, offering researchers methodologies to quantify brain flexibility and state transitions relevant to the addiction cycle. By applying NCT, scientists can model the neuroadaptations that occur across the binge/intoxication, withdrawal/negative affect, and preoccupation/anticipation stages of addiction, potentially identifying novel biomarkers and treatment targets [8].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is Network Control Theory and how is it relevant to addiction research?

Network Control Theory is a mathematical framework from engineering that models how external control signals can steer a system's dynamics toward a desired state. When applied to neuroscience, NCT uses the brain's structural connectome to understand how activity in one region influences others. For addiction research, this is particularly valuable for modeling transitions between the different stages of the addiction cycle and understanding how control energy requirements differ between individuals with and without substance use disorders [23]. Recent studies have shown that heavy alcohol use alters structural connectivity and functional brain dynamics, which can be quantified using NCT [24].

Q2: What are the key NCT metrics for studying brain flexibility in addiction?

The table below summarizes the primary NCT metrics used to study brain flexibility:

Table: Key NCT Metrics for Brain Flexibility Research

| Metric | Definition | Interpretation in Addiction |

|---|---|---|

| Control Energy | Amount of input required for state transitions [23] | Higher energy may indicate rigid, compulsive states [24] |

| Average Controllability | Node's ability to spread impulse across network [23] | Identifies hubs that may drive craving or relapse |

| Modal Controllability | Node's ability to drive difficult-to-reach states [23] | Potential for accessing non-habitual brain states |

| Intrinsic Neural Timescales (INTs) | Temporal specialization of brain regions [24] | May reflect tolerance to drug effects or recovery processes |

Q3: What are the data requirements for applying NCT to addiction neurobiology?

NCT requires both structural and functional neuroimaging data. The structural connectome is typically derived from diffusion tensor imaging (DTI), which maps white matter fiber tracts between brain regions. Functional data from fMRI provides information on brain states. For addiction research specifically, it's valuable to collect data during tasks or states relevant to the addiction cycle (e.g., cue exposure, withdrawal states) to define meaningful initial and target states for NCT analyses [23] [24].

Q4: How can NCT help identify individual differences in addiction vulnerability?

Individual differences in addiction vulnerability may manifest as variations in network controllability properties. NCT can quantify how efficiently individuals can transition between brain states, with potentially lower control energy requirements for state transitions associated with greater cognitive flexibility and resilience against addictive patterns. Conversely, higher control energy requirements might reflect the compulsivity and rigid behavioral patterns observed in later stages of addiction [14] [8] [24].

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Issues

Problem: Inconsistent control energy calculations across research sites

Solution: Implement standardized preprocessing pipelines for structural connectome construction. Key steps include:

- Use consistent parcellation schemes (e.g., AAL, Desikan-Killiany)

- Apply quality control metrics for tractography (e.g., fractional anisotropy thresholds)

- Normalize connection weights using standardized approaches (e.g., streamline count with proportional scaling)

- Validate NCT outputs with null network models to ensure results reflect true network properties rather than computational artifacts [23]

Problem: Relating NCT metrics to clinical measures of addiction severity

Solution:

- Collect comprehensive phenotypic data including addiction severity scales (e.g., AUDIT, DAST)

- Map NCT metrics to the three-stage addiction cycle model:

- Binge/Intoxication: Examine control energy for transitions to reward-related states

- Withdrawal/Negative Affect: Analyze transitions involving stress and emotion networks

- Preoccupation/Anticipation: Study controllability of executive control networks [8]

- Use multivariate approaches to account for comorbidities that may influence network dynamics [25]

Problem: Integrating NCT with molecular targets for drug development

Solution: Leverage transcriptomic and receptor distribution data from resources like the Allen Human Brain Atlas to connect NCT findings with potential pharmacological targets. Recent research has demonstrated relationships between NCT metrics and distributions of specific neurotransmitter receptors (e.g., serotonin 2a receptors), providing a bridge between network-level dynamics and molecular interventions [24].

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Calculating Control Energy for State Transitions

Purpose: To quantify the energy required to transition between brain states relevant to addiction.

Materials:

- Structural connectome (n × n adjacency matrix)

- Definition of initial and target brain states (n × 1 vectors)

- NCT computational environment (e.g., NCTPy Python package) [23]

Procedure:

- Define State Vectors: Represent neural states using activity patterns from fMRI data. For addiction studies, define states relevant to the addiction cycle (e.g., craving state, satiety state).

- Formulate Control Problem: Use the discrete-time linear time-invariant system model:

x(t+1) = Ax(t) + Bu(t)[23] Where A is the structural connectome, x(t) is the state vector, and u(t) is the control input. - Compute Optimal Control Inputs: Solve for the control inputs that minimize the energy function:

E = Σ[u(t)ᵀu(t)][23] - Compare Groups: Calculate and compare control energy between individuals with substance use disorders and healthy controls for the same state transitions.

Table: Parameters for Control Energy Calculation

| Parameter | Description | Recommended Setting |

|---|---|---|

| System Matrix (A) | Structural connectome | Normalized by largest eigenvalue |

| Control Matrix (B) | Nodes receiving input | Identity matrix for full control |

| Time Horizon | Steps for transition | T = 10 for discrete model |

| State Constraints | Bounds on neural activity | -1 to 1 for normalized states |

Protocol 2: Assessing Regional Controllability in Addiction

Purpose: To identify brain regions with altered controllability properties in addiction.

Materials:

- Structural connectomes from participants with substance use disorders and matched controls

- Parcellated fMRI data during rest and task conditions

- Computational resources for network analysis

Procedure:

- Compute Average Controllability: For each brain region, calculate the average controllability metric, which measures a node's ability to steer the brain into easily reachable states [23].

- Compare Between Groups: Use appropriate statistical tests (e.g., ANCOVA controlling for age, sex) to identify regions with significant differences in controllability between groups.

- Relate to Addiction Stages: Map regions with altered controllability to the three-stage addiction model:

- Validate with Behavioral Measures: Correlate controllability metrics with clinical assessments of addiction severity and cognitive function.

NCT Data Analysis Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the complete workflow for applying NCT to addiction research:

NCT Analysis Workflow for Addiction Research

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table: Essential Resources for NCT Addiction Research

| Resource Type | Specific Examples | Application in NCT Addiction Research |

|---|---|---|

| Neuroimaging Data Repositories | Human Connectome Project, MICAMICs [24] | Source of standardized connectome data for control group comparisons |

| Computational Tools | NCTPy Python package [23] | Implementation of core NCT algorithms and metrics |

| Gene Expression Atlases | Allen Human Brain Atlas [24] | Linking NCT findings to molecular targets |

| Clinical Assessment Tools | Addiction Severity Index, Penn Alcohol Craving Scale | Correlating NCT metrics with clinical measures |

| Parcellation Schemes | AAL, Desikan-Killiany, Schaefer atlases | Standardized brain region definitions for cross-study comparisons |

Key Signaling Pathways in Addiction Neurobiology

The following diagram illustrates the primary neurocircuits involved in the addiction cycle, which serve as key systems for NCT analysis:

Neurocircuits of the Addiction Cycle

The Adolescent Brain Cognitive Development (ABCD) Study is a landmark longitudinal study on brain development and child health supported by the National Institutes of Health (NIH). This landmark research project aims to increase our understanding of environmental, social, genetic, and other biological factors that affect brain and cognitive development, ultimately seeking to identify factors that can enhance or disrupt a young person's life trajectory [26]. The study represents the largest long-term investigation of brain development and child health ever conducted in the United States, with nearly $290 million in new funding recently allocated for an additional seven years of research [26].

The ABCD Study's relevance to addiction neurobiology is profound, particularly in understanding individual differences in vulnerability to substance use disorders. The study was originally conceived to "examine risk and resiliency factors associated with the development of substance use" but has since expanded to inform our understanding of how biospecimens, neural alterations, and environmental factors contribute to both healthy behavior and risk for poor mental and physical outcomes [27]. By tracking participants from ages 9-10 into young adulthood, the ABCD Study provides unprecedented insight into the developmental trajectories that lead to substance use initiation, progression, and potential addiction, with a particular focus on individual differences in neurobiological susceptibility.

ABCD Study Design and Methodology

Cohort Composition and Recruitment

The ABCD Study employs a comprehensive, multi-faceted approach to recruitment and retention, ensuring a representative sample of the U.S. adolescent population:

Table: ABCD Study Cohort Characteristics

| Characteristic | Specification |

|---|---|

| Total Enrollment | 11,880 children [26] |

| Age at Baseline | 9-10 years old [26] |

| Recruitment Sites | 21 sites across the United States [27] |

| Study Duration | Planned follow-up for 10 years into young adulthood [26] [27] |

| Recruitment Method | Multi-stage probability sample including stratified random sample of schools [27] |

The study completed enrollment for the baseline sample in October 2018, with the goal of retaining approximately 10,000 participants into early adulthood [26]. The recruitment strategy employed a multi-stage probability sample including a stratified random sample of schools to ensure demographic diversity and representativeness [27].

Data Collection Domains and Assessment Schedule

The ABCD Study collects a wealth of multimodal data through repeated assessments at specified intervals:

Table: ABCD Study Data Collection Domains and Schedule

| Domain | Specific Measures | Assessment Schedule |

|---|---|---|

| Neuroimaging | Structural MRI (T1w, T2w), resting-state fMRI, task fMRI (Monetary Incentive Delay, Stop-Signal, Emotional N-Back), diffusion MRI [28] | Approximately every 2 years for neuroimaging; more frequently for behavioral assessments [29] |

| Cognitive Assessment | NIH Toolbox, neuropsychological tests [27] | Regular intervals (e.g., 6 months) [29] |

| Mental & Physical Health | K-SADS, ASEBA, mental health disorders, physical health metrics [27] | Regular intervals throughout study |

| Biospecimens | DNA, RNA, plasma, serum, cortisol, pubertal hormones [27] | Collected at baseline and follow-ups |

| Environmental Factors | Family history, cultural identification, school environment, neighborhood characteristics [27] | Ongoing assessment |

| Substance Use | Timeline Followback, substance use initiation and patterns [27] | Regular monitoring, especially during high-risk periods |

Behavioral and clinical assessments are administered at shorter intervals than neuroimaging assessments [29]. This comprehensive approach allows researchers to examine how various factors interact across development and how individual differences in these domains may predict substance use trajectories.

Technical Support Center: ABCD Data Access and Management

Data Access Frequently Asked Questions

How do I access ABCD Study data? ABCD data are publicly shared with eligible researchers with a valid research use of the data at a research institution. Researchers must visit the NBDC Datahub or the ABCD Study website for detailed information on how to access and download the data [28].

Can researchers from non-U.S. institutions access the data? Yes, researchers from international institutions with an active Federal Wide Assurance (FWA) can access ABCD data. Many international researchers have successfully accessed and published with ABCD Study data [28].

Is there a cost to access the data? No, there is no cost to access the ABCD Study dataset [28].

Do I need IRB approval to use ABCD data? Institutional requirements vary regarding de-identified datasets. Some institutions require expedited or exempt IRB reviews, while others do not consider working with de-identified data to constitute human subjects research. Researchers should consult their local IRB for guidance [28].

Can students or trainees access ABCD data? Lead investigators may obtain Data Use Certificates (DUCs) that include trainees, lab members, and collaborators at their institution. The lead investigator is responsible for ensuring compliance with DUC terms and conditions and must renew the DUC annually [28].

Data Analysis Troubleshooting Guide

Issue: Inconsistent imaging data quality across sites Solution: The ABCD Study has implemented rigorous quality control procedures including standardized acquisition protocols across all 21 sites. The minimally processed neuroimaging data have undergone standard modality-specific preprocessing stages including conversion from raw to compressed files, distortion correction, movement correction, alignment to standard space, and initial quality control [28]. Researchers should consult the imaging documentation for quality control metrics and exclude participants based on established QC criteria.

Issue: Cerebellum cutoff in fMRI and dMRI data Explanation: Due to relatively tight brain coverage for dMRI and fMRI acquisitions, the superior or inferior edge of the brain is sometimes outside of the stack of slices, a phenomenon called "field of view (FOV) cutoff" [28]. Solution: The ABCD Study provides automated post-processing QC metrics that include measures of superior and inferior FOV cutoff. Researchers can use these metrics to exclude participants with significant FOV cutoff from analyses. In tabulated imaging data, brain regions outside the FOV have missing values, but other regions remain usable [28].

Issue: Multiple dMRI series for Philips scanners Explanation: For imaging data from Philips scanners, the dMRI acquisition is split into two series due to a platform limitation. Both scans have the same phase-encode polarity and are meant to be concatenated together [28]. Solution: For minimally processed data, one scan is selected for each session based on QC ratings, except for Philips scanners, in which case two are selected for packaging and sharing. Researchers working with Philips scanner data should ensure proper concatenation of these series.

Issue: When should field maps be used? Solution: The "minimally processed" images have already been corrected for B0 distortion using field maps, so field maps are not necessary for these data. However, if researchers are working with "fast track" unprocessed data, they would need to perform distortion correction using the field maps provided in Fast Track [28].

Methodological Protocols for Key ABCD Experiments

Neuroimaging Acquisition and Processing Protocol

The ABCD Study employs a comprehensive neuroimaging protocol across all 21 sites:

Structural Imaging:

- High-resolution 3D T1-weighted (T1w) and T2-weighted (T2w) scans

- Parameters: Consistent across sites with standardized sequences

- Processing: Includes alignment to standard space and quality control metrics

Functional MRI:

- Resting-state fMRI: Eyes-open fixation

- Task-based fMRI: Monetary Incentive Delay (reward processing), Stop-Signal Task (response inhibition), Emotional N-Back (working memory and emotion regulation)

- Preprocessing: Distortion correction, movement correction, alignment to standard space

Diffusion MRI:

- Multiple b-values and directions for advanced diffusion modeling

- Processing: Diffusion gradients adjusted for head rotation, provided as bvecs.txt and bvals.txt files

- Registration: Rigid-body transformation matrix provided for registration between dMRI and corresponding T1w image

The minimally processed imaging data are shared in BIDS-formatted directory trees as NIfTI files, accompanied by JSON files containing imaging metadata derived from original DICOM files [28].

Genetic and Biospecimen Collection Protocol

The ABCD Study collects and processes various biospecimens through a standardized protocol:

- Blood samples: Processed for DNA, RNA, plasma, serum, and cryopreserved lymphocytes

- Saliva samples: Alternative source for genetic material

- Analysis coordination: RUCDR Infinite Biologics at Rutgers University provides materials for collecting samples and performs genetic/epigenetic analyses [29]

- Banking: Biospecimens are banked for future analyses to be determined later

For researchers interested in additional assays, NIDA has developed a mechanism for requesting biosamples through the NBDC biospecimen access program [28].

ABCD Neuroimaging Acquisition Workflow

Investigating Individual Differences in Addiction Neurobiology Using ABCD Data

Theoretical Frameworks for Individual Differences in Addiction

Understanding individual differences in addiction susceptibility requires comprehensive theoretical models that account for neurobiological variability:

The Opponent-Process Theory: Developed by Solomon and Corbit, this theory suggests that when a positive affective response is activated by drug use, an opposing negative response is simultaneously triggered to restore homeostasis. With repeated drug use, the opponent process intensifies, leading to tolerance and withdrawal symptoms [30]. Individual differences in the strength and timing of these processes may explain variability in addiction vulnerability.

Dopaminergic Hypothesis of Addiction: This framework posits that drugs of abuse act through a common mechanism of increasing dopamine in the brain's reward system, particularly the mesolimbic pathway projecting from the ventral tegmental area to the nucleus accumbens [30]. Individual differences in baseline dopamine function or receptor density may moderate susceptibility to addiction.

Three-Stage Addiction Cycle Model: Koob's model conceptualizes addiction as progressing through binge/intoxication, withdrawal/negative affect, and preoccupation/anticipation stages, each with distinct neurobiological substrates [14]. Individual differences may manifest in the propensity to transition between these stages.

Oxytocin System Influence: Recent research indicates that individual differences in the endogenous oxytocin system, shaped by genetic variation and early environmental influences, may affect susceptibility to addiction through interactions with stress systems, neurotransmitter systems, and reward pathways [31].

Analyzing Individual Differences in ABCD Data

The ABCD Study provides unique opportunities to investigate individual differences in addiction neurobiology through several analytical approaches:

Twin Studies: The ABCD cohort includes twin pairs, allowing researchers to disentangle genetic and environmental contributions to substance use outcomes [27].

Longitudinal Growth Modeling: Repeated assessments enable tracking of individual trajectories in brain development, cognitive function, and behavior, identifying patterns associated with substance use initiation.

Machine Learning Approaches: Large sample size permits development of predictive models identifying neurobiological, cognitive, and environmental features associated with substance use outcomes.

Gene-Environment Interactions: Comprehensive genetic and environmental data allow examination of how specific genetic profiles interact with environmental factors to influence substance use risk.

Table: Key Research Reagent Solutions for ABCD Data Analysis

| Tool/Resource | Function | Access Point |

|---|---|---|

| NBDC Data Hub | Primary data access portal for ABCD data | https://data-archive.nimh.nih.gov/abcd |

| BIDS Format Data | Standardized neuroimaging data structure | ABCD Data Releases |

| PhenX Toolkit | Common measures for cross-study comparisons | https://www.phenxtoolkit.org/ |

| NIH Toolbox | Standardized cognitive assessment metrics | https://www.healthmeasures.net/ |

| FreeSurfer Output | Structural MRI processing outputs | Included in BIDS derivatives |

| ABCD Harmonized Code | Standardized processing pipelines | ABCD Study Resources |

Advanced Analytical Approaches for Individual Differences Research

Machine Learning Applications for Predicting Substance Use Outcomes

Recent research demonstrates the power of machine learning approaches for identifying individual differences in addiction susceptibility:

Functional Network Connectivity Predictive Models: Research by investigators outside the ABCD Study has shown that machine learning pattern classification models using functional network connectivity can predict with approximately 80% accuracy which individuals will complete substance abuse treatment programs [32]. Similar approaches can be applied to ABCD data to identify youth at highest risk for problematic substance use.

Key Predictive Features:

- Connectivity between anterior cingulate cortex, striatum, and insula

- Executive control network integrity

- Salience network function

- Default mode network regulation

These approaches highlight how neurobiological individual differences can be leveraged to predict real-world outcomes relevant to addiction.

Multilevel Modeling of Individual Differences

The ABCD dataset enables sophisticated multilevel modeling approaches:

Cross-Level Interactions: Examining how genetic factors moderate neural responses to environmental stressors Developmental Timing Effects: Investigating how the timing of substance use initiation interacts with neurodevelopmental trajectories Resilience Factors: Identifying protective factors that buffer against substance use despite high-risk profiles

Framework for Individual Differences in Addiction Vulnerability

Frequently Asked Questions on ABCD Study Applications

How can I propose new assays for collected biospecimens? NIDA has developed a mechanism for requesting biosamples through the NBDC biospecimen access program. All currently analyzed specimens are part of the data release, and researchers can petition for additional assays [28].

Are there assessments of autism spectrum disorder in the ABCD sample? The ABCD Study exclusion criteria included "a current diagnosis of schizophrenia, autism spectrum disorder (moderate, severe), intellectual disability, or alcohol/substance use disorder." While ABCD does not maintain comprehensive assessments related to diagnosed ASD, the KSADS includes diagnostic categories, including autism spectrum disorder based on parent report only [28].

Can I use AI tools like ChatGPT to analyze ABCD data? No, inputting ABCD data to generative AI tools such as ChatGPT is a violation of the terms of use outlined in the data use agreement [28].

Where can I find detailed information about specific measures used in ABCD? The ABCD Study provides extensive documentation on their website, including information about study design and protocols in the Scientist section. However, many specific measures are proprietary and cannot be shared [28].

How is substance use assessed in the ABCD Study? Substance use assessment includes the Timeline Followback method for detailed substance use history, along with regular monitoring of substance use initiation and patterns, particularly during high-risk developmental periods [27].

The ABCD Study represents an unprecedented resource for investigating individual differences in addiction neurobiology. By providing comprehensive, longitudinal data across multiple domains, it enables researchers to examine how genetic, neural, cognitive, and environmental factors interact across development to influence substance use trajectories. The technical support resources outlined in this article provide essential guidance for researchers navigating this complex dataset and leveraging it to advance our understanding of why individuals differ in their susceptibility to addiction.

As the ABCD cohort progresses through adolescence and into young adulthood—the period of highest risk for substance use initiation and progression—the value of this dataset will continue to grow. Future directions include examining the transition from initial substance use to regular use and disorder, identifying neurodevelopmental factors that predict treatment response, and elucidating the mechanisms underlying resilience despite high-risk profiles. Through continued analysis of this rich dataset, the research community moves closer to personalized prevention and intervention approaches that account for the fundamental individual differences in addiction neurobiology.

Genome-Wide Association Studies (GWAS) and the Genetically Informed Neurobiology of Addiction (GINA) Model

GWAS & GINA Model FAQ: Core Concepts for Researchers

FAQ 1: What is the primary objective of a Genome-Wide Association Study (GWAS) in addiction research?

A Genome-Wide Association Study (GWAS) is a research approach that tests hundreds of thousands of genetic variants across many genomes to identify those statistically associated with a specific trait or disease, such as substance use disorder [33] [34]. In addiction research, its goal is to pinpoint specific genomic loci and genetic architectures that contribute to an individual's liability for addiction, thereby providing insights into the underlying biology of this complex brain disorder [35] [36].

FAQ 2: How does the GINA model advance previous neurobiological theories of addiction?

The Genetically Informed Neurobiology of Addiction (GINA) model integrates findings from large-scale genomic studies with established brain-based models of addiction [35] [37]. It proposes that genetic liability to addiction is composed of two main components: a general, broad-spectrum liability that cuts across different substances and disorders, and substance-specific genetic risks [35] [38]. This model uses genomic evidence to inform our understanding of how addiction unfolds dynamically across the lifespan, moving beyond theories that focused predominantly on substance-induced neural changes [35].

FAQ 3: What is the key genetic distinction between substance use and a substance use disorder (SUD)?

GWAS results reveal a moderate to high genetic correlation between ever using a substance (e.g., ever smoking) and developing a disordered pattern of use (e.g., nicotine dependence) [35]. However, they are not genetically identical. Crucially, substance use and substance use disorders can show opposing genetic correlations with other outcomes like educational attainment and certain health conditions, highlighting the importance of carefully defining phenotypic traits in genetic studies [35].

FAQ 4: What is the polygenic architecture of addiction, and what does it imply for research?

Addiction is highly polygenic, meaning risk is influenced by many genetic variants, each with a very small individual effect size [33] [39]. This architecture explains why very large sample sizes are required for GWAS to have sufficient power to detect these variants reliably. It also underscores that there is no single "addiction gene"; rather, risk emerges from the aggregate of thousands of common and rare genetic variations [39] [36].

Troubleshooting Common GWAS Workflow Issues