In Vivo Techniques in Neuroscience: A Comprehensive Guide for Research and Drug Development

This article provides a comprehensive overview of current in vivo techniques for neuroscience research, tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals.

In Vivo Techniques in Neuroscience: A Comprehensive Guide for Research and Drug Development

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of current in vivo techniques for neuroscience research, tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals. It explores the foundational principles of methods like optical imaging and in vivo SELEX, details their practical applications in disease modeling and therapeutic discovery, addresses key troubleshooting and optimization challenges in translational settings, and offers a critical comparative analysis with in vitro and ex vivo approaches. The synthesis aims to bridge the gap between basic research and clinical application, empowering scientists to select appropriate methodologies and advance the development of novel therapeutics for neurological disorders.

Core Principles and the Power of In Vivo Brain Mapping

In vivo research, defined as investigations conducted within a living organism, is a cornerstone of biological and medical science. The term itself, derived from Latin meaning "within the living," encompasses studies performed in complex, integrated systems where all physiological processes remain intact [1]. This approach stands in contrast to in vitro ("in glass") methods, which are conducted in artificial environments outside of living organisms, such as petri dishes or test tubes [1].

The fundamental value of in vivo research lies in its capacity to reveal the true physiological behavior of biological systems, accounting for the intricate interplay between organs, tissues, cells, and molecular pathways that cannot be fully replicated in simplified in vitro settings [1] [2]. This is particularly critical in neuroscience research, where the complexity of the central nervous system, with its networked electrical signaling, blood-brain barrier dynamics, and multifaceted cellular interactions, demands investigation in intact organisms to generate clinically relevant insights [2]. In vivo models provide indispensable platforms for investigating pathophysiological mechanisms underlying neurological disorders and for conducting preclinical translational studies that may include the assessment of new treatments [1] [2].

Fundamental Principles and Physiological Relevance

Core Characteristics of In Vivo Systems

In vivo research operates on the principle that biological systems function as integrated wholes rather than as isolated components. This holistic approach captures the essential complexity of living organisms through several defining characteristics:

- Whole-organism complexity: Investigations account for systemic interactions between multiple organ systems, hormonal regulation, metabolic integration, and neural networking that collectively influence experimental outcomes [1].

- Intact physiological environment: Studies maintain natural barriers (e.g., blood-brain barrier), vascular perfusion, immune responses, and homeostatic mechanisms that significantly influence biological responses [2].

- Functional readouts: Researchers can measure complex behavioral, cognitive, and physiological endpoints that reflect integrated system function rather than isolated cellular responses [2].

Comparative Advantages and Limitations

The following table summarizes the key distinctions between in vivo research and alternative methodological approaches:

Table 1: Comparison of Research Methodological Approaches

| Parameter | In Vivo | In Vitro | In Silico |

|---|---|---|---|

| System Complexity | Whole living organism with intact physiology | Isolated cells, tissues, or organs in artificial environment | Computational models and simulations |

| Physiological Relevance | High - includes systemic interactions | Limited - lacks systemic context | Variable - depends on model accuracy |

| Throughput | Lower throughput, time-intensive | Higher throughput, rapid results | Highest throughput, instantaneous |

| Cost Implications | High (animal care, ethical oversight) | Moderate (reagents, cell culture) | Low (computational resources) |

| Regulatory Pathway | Required for preclinical drug development | Early screening and mechanism studies | Predictive modeling and hypothesis generation |

| Species Differences | Potential for cross-species translation bias | Human cells possible but lack systemic context | Species-specific parameters can be implemented |

While in vivo approaches offer unparalleled physiological relevance, researchers must acknowledge several methodological considerations. The selection of appropriate animal models is critical, as species with varying genetic backgrounds, environmental adaptations, and pathway differences can bias preclinical interpretations [1]. Additionally, the resource-intensive nature of in vivo studies, including costs, time investment, and ethical considerations, necessitates careful experimental design to maximize information yield while minimizing animal usage [3].

In Vivo Methodologies in Neuroscience Research

Advanced Neuroimaging and Modulation Techniques

Contemporary neuroscience employs sophisticated technologies for observing and manipulating neural activity in living organisms:

Optogenetics: This neurostimulation technique uses low-intensity light with different waveforms to produce or modulate electrophysiological responses in genetically modified neurons, opening promising revolutionary applications in neurological therapeutics in in vivo preclinical studies [2]. The approach involves viral vector-mediated expression of light-sensitive proteins (opsins) such as channelrhodopsin-2 (ChR2) in specific neuronal populations, enabling precise temporal control of neural activity with millisecond precision [2].

Chemogenetics: This forefront technique frequently uses the in vivo injection of a viral vector to induce the expression of genetically modified G-protein coupled receptors (GPCR), which are inert for endogenous ligands but specifically activated by "designer drugs" [2]. These expressed receptors are termed DREADDs (Designer Receptors Exclusively Activated by Designer Drugs), enabling remote control of neural activity without implanted hardware [2].

Two-photon laser scanning microscopy: This imaging method enables deep tissue imaging in living animals, allowing researchers to observe dynamic processes such as the emergence and disappearance of dendritic spines in adult mice and dynamic changes in dendrites and axons during development [2]. When combined with fluorescent calcium indicators, this technique permits functional imaging of neural activity in intact circuits [2].

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI): This non-invasive multiplanar imaging technique helps investigate biological functions with both functional and structural images showing both activity and anatomy [2]. Recent development of MRI machines for laboratory animals has accelerated its use in in vivo preclinical investigations, providing critical information about neurological disorders [2].

Analytical and Monitoring Approaches

The quest for real-time monitoring of living systems has driven the development of specialized analytical approaches for in vivo measurements:

Solid phase microextraction (SPME): This non-exhaustive sample preparation technique involves using a small amount of extraction phase mounted on a solid support exposed for a defined time in the sample matrix [4]. Its unique features include combining sample preparation, isolation, and enrichment into a single step while reducing sample preparation time [4]. The miniaturized and minimally invasive nature of SPME makes it particularly suitable for in vivo applications in animal models and humans.

Microdialysis: This flow-through sampling technique involves implanting a small probe with a semi-permeable membrane into tissue to continuously collect analytes from the extracellular fluid [4]. The critical requirement for in vivo microdialysis is biocompatibility of all materials contacting extracellular fluids and perfusate to protect both the microdialysis probe and the specimen being sampled [4].

Wearable sensors and devices: These noninvasive, on-body chemical sensors interface with biological fluids like saliva, tears, sweat, and interstitial fluid instead of blood, enabling real-time monitoring of physiological parameters [4]. Modern technological advances in digital medicine and mobile applications have accelerated the development of new wearable devices with a multitude of applications in neuroscience research [4].

Table 2: Key In Vivo Analytical Techniques and Their Applications in Neuroscience

| Technique | Principle | Temporal Resolution | Key Applications | Materials Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Solid Phase Microextraction (SPME) | Equilibrium-based extraction onto coated fiber | Minutes to hours | Monitoring neurotransmitters, metabolites, drugs | Biocompatible coatings: C18, PAN, carbon mesh |

| Microdialysis | Diffusion across semi-permeable membrane | Minutes | Neurochemical monitoring, pharmacokinetic studies | Biocompatible membranes: polycarbonate, polyether sulfone |

| Wearable Sensors | Electrochemical or optical detection | Continuous real-time | Physiological monitoring, biomarker tracking | Flexible substrates, biocompatible hydrogels |

| Two-photon Microscopy | Nonlinear optical excitation | Seconds to minutes | Cellular imaging in deep brain structures | Specialized cranial windows, fluorescent indicators |

Quantitative Frameworks and Experimental Design

Pharmacokinetic/Pharmacodynamic (PK/PD) Modeling

The translation of in vitro findings to in vivo efficacy represents a significant challenge in drug development. Quantitative pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic (PK/PD) modeling establishes relationships among dose, exposure, and efficacy, enabling prediction of in vivo outcomes from in vitro data [3]. Remarkably, research has demonstrated that in vivo tumor growth dynamics may be predicted from in vitro data when linking in vivo PK corrected for fraction unbound with a PK/PD model that quantitatively integrates knowledge of relationships among drug exposure, pharmacodynamic response, and cell growth inhibition collected solely from in vitro experiments [3].

This approach requires diverse experimental data collected with high dimensionality across time and dose, including target engagement measurements, biomarker levels, drug-free cell growth, drug-treated cell viability, and pharmacokinetic parameters [3]. The implementation of such models can significantly reduce animal usage while enabling the collection of denser time course and dose response data in more controlled systems [3].

Research Reagent Solutions for In Vivo Neuroscience

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for In Vivo Neuroscience Studies

| Reagent/Material | Function/Purpose | Example Applications |

|---|---|---|

| Viral Vectors (AAV, CAV2, Lentivirus) | Gene delivery for expression of sensors, opsins, or DREADDs | Selective transduction of specific neuronal populations [2] |

| Chemical Indicators (Calcium-sensitive dyes) | Monitoring neural activity via calcium flux | Functional imaging of circuit dynamics [2] |

| DREADDs (Designer Receptors) | Chemogenetic control of neural activity | Remote modulation of neuronal firing without implants [2] |

| Opsins (Channelrhodopsin, Halorhodopsin) | Optogenetic control of neural activity | Precise temporal control of neuronal activity with light [2] |

| Biocompatible Probes | Neural interface for recording or stimulation | Chronic implantation for electrophysiology [4] |

| MRI Contrast Agents | Enhance tissue contrast for structural and functional imaging | Tracking morphological changes in disease models [2] |

Experimental Protocols for Key In Vivo Methods

Protocol: Chemogenetic Modulation of Neuronal Circuits

This protocol outlines the use of chemogenetics for modulating specific neuronal populations in rodent models:

Stereotaxic Viral Injection:

- Anesthetize animal and secure in stereotaxic frame.

- Identify coordinates for target brain region using brain atlas.

- Perform craniotomy and inject recombinant viral vector (e.g., CAV2-hM3Dq) expressing DREADDs into target region [2].

- Optimal conditions identified include low and medium volume with 0.1 × 10^9 viral particles of CAV2 for safe and specific transduction [2].

Post-operative Recovery:

- Allow 2-4 weeks for adequate gene expression before experiments.

- Monitor animals for any signs of distress or neurological impairment.

Receptor Activation:

- Administer designer drug (e.g., Clozapine-N-oxide, CNO) via appropriate route (i.p. injection, oral gavage).

- Doses typically range from 0.1-5 mg/kg depending on the specific DREADD variant [2].

Functional Assessment:

- Conduct behavioral tests, electrophysiological recordings, or imaging studies to evaluate functional outcomes.

- Include appropriate controls (vehicle injection, empty vector controls).

Protocol: In Vivo Solid Phase Microextraction for Neurochemical Monitoring

This protocol describes the implementation of SPME for monitoring neurotransmitters and metabolites in living brain tissue:

SPME Probe Preparation:

- Select appropriate fiber coating based on target analytes (C18, PAN, carbon mesh).

- Condition fibers according to manufacturer specifications.

- Verify extraction efficiency and reproducibility in vitro before in vivo application [4].

Surgical Implantation:

- Anesthetize animal and secure in stereotaxic apparatus.

- Perform craniotomy at target coordinates.

- Slowly implant SPME probe into brain region of interest.

- Secure probe to skull using dental cement.

Sampling Period:

- Allow equilibrium period (typically 15-30 minutes) for analyte extraction.

- Maintain animal under anesthesia or use chronic implantation for freely moving samples.

Sample Processing:

- Carefully remove SPME probe from brain tissue.

- Desorb analytes using appropriate solvent (typically methanol or acetonitrile/water mixtures).

- Analyze extracts using LC-MS/MS or other appropriate analytical platforms [4].

Data Analysis:

- Quantify analytes using calibration curves generated with isotope-labeled standards.

- Normalize results to extraction time and probe characteristics.

- Perform statistical analysis comparing experimental groups.

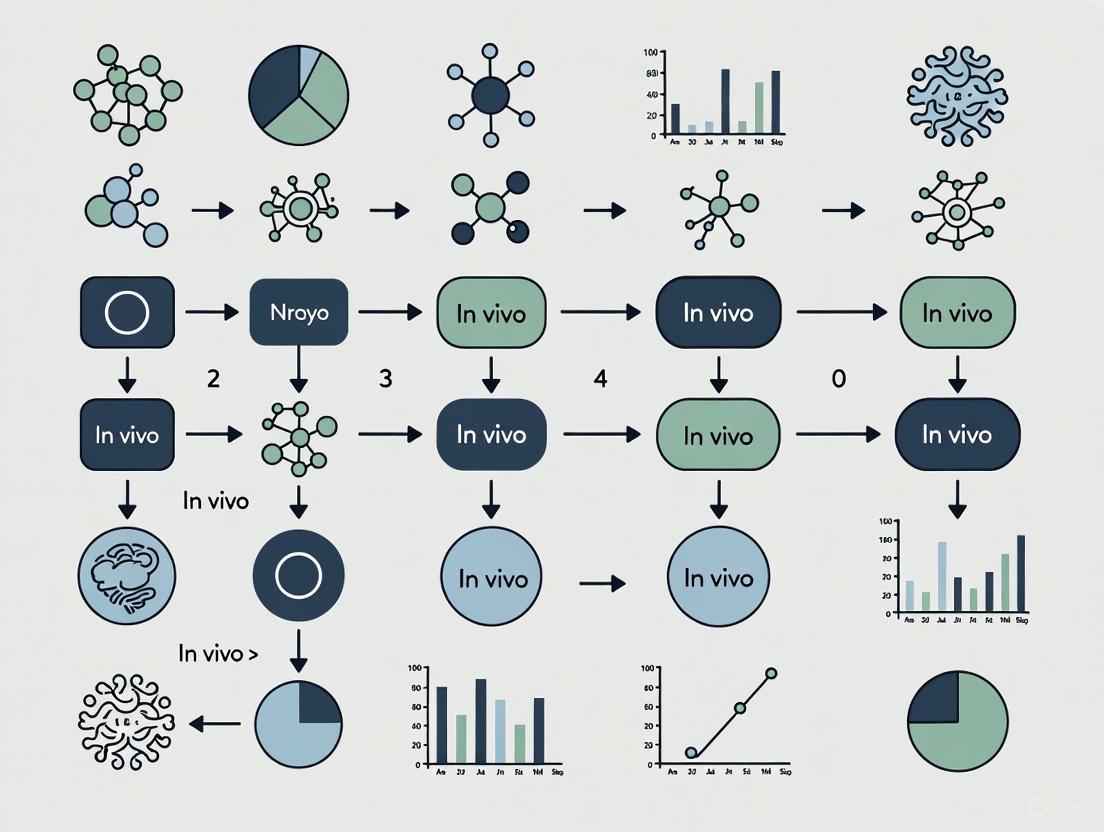

Visualization of In Vivo Research Concepts

Workflow for Integrating In Vitro and In Vivo Research

In Vitro to In Vivo Prediction Workflow

In Vivo Neural Circuit Investigation Techniques

Neural Circuit Investigation Methods

In vivo optical imaging has revolutionized neuroscience by enabling researchers to observe brain structure and function in living organisms. These technologies provide unparalleled sensitivity to functional changes through intrinsic contrast or a growing arsenal of exogenous optical agents, allowing scientists to study the dynamic processes of the brain in its native state [5]. The field encompasses a wide spectrum of techniques, each designed to overcome the fundamental challenge of light scattering in biological tissue, from non-invasive near-infrared imaging for human clinical applications to high-resolution microscopy for cellular-level investigation in animal models [5].

This technical guide provides neuroscientists and drug development professionals with a comprehensive overview of major in vivo imaging modalities, focusing on their operating principles, applications, and implementation considerations. We examine techniques ranging from macroscopic cortical imaging to microscopic cellular resolution methods, with particular emphasis on near-infrared spectroscopy (NIRS) and two-photon microscopy as cornerstone technologies in modern neuroscience research.

Core Imaging Modalities: Technical Principles and Applications

Comparative Analysis of Major Techniques

Table 1: Technical specifications of major in vivo optical imaging modalities

| Imaging Modality | Spatial Resolution | Penetration Depth | Temporal Resolution | Primary Applications in Neuroscience | Key Advantages |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Functional NIRS (fNIRS) | ~1-3 cm (diffuse imaging) | 5-8 mm (cortical surface) [6] | 0.1-10 Hz [7] | Functional neuroimaging, hemodynamic monitoring, cognitive studies [7] [6] | Portable, non-invasive, compatible with other tasks, measures both HbO and HbR [7] [6] |

| Two-Photon Microscopy | Sub-micron to micron level [8] | Up to ~1 mm in neocortex [8] | Milliseconds to seconds (depending on scanning area) | Cellular and subcellular imaging, calcium dynamics, dendritic spine morphology [8] [9] | High-resolution deep tissue imaging, minimal out-of-focus photobleaching [8] |

| Macroscopic Cortical Imaging | 10-100 μm [5] | Superficial cortical layers | 0.1-10 Hz | Cortical mapping, hemodynamic response to stimuli, epilepsy focus identification [5] | Wide-field imaging, intrinsic contrast, simple implementation |

| Optoacoustic Neuro-tomography | Tens to hundreds of microns [10] | Several millimeters to centimeters | Seconds to minutes | Whole-brain functional imaging with calcium indicators [10] | Deep penetration, combines optical contrast with ultrasound resolution |

| Expansion Microscopy | ~15-25 nm (after expansion) [11] | Limited by physical sectioning | N/A (fixed tissue) | Ultrastructural analysis, protein localization, synaptic architecture [11] | Nanoscale resolution with standard microscopes, molecular specificity |

Table 2: Molecular contrast mechanisms in optical brain imaging

| Contrast Mechanism | Measured Parameters | Imaging Modalities | Typical Labels/Dyes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hemodynamic | Oxyhemoglobin (HbO), deoxyhemoglobin (HbR) concentration changes [7] [5] | fNIRS, macroscopic imaging, DOT | Intrinsic contrast (no labels required) |

| Calcium Dynamics | Neuronal spiking activity via calcium flux [8] [10] | Two-photon microscopy, optoacoustic tomography | Genetically encoded indicators (GCaMP, NIR-GECO2G) [10], synthetic dyes |

| Voltage-Sensitive | Membrane potential changes [5] | Macroscopic cortical imaging, two-photon microscopy | Voltage-sensitive dyes (VSDs) |

| Structural/Morphological | Cell morphology, dendritic spines, synaptic structures [8] [11] | Two-photon microscopy, expansion microscopy | Fluorescent proteins, pan-staining dyes [11] |

| Metabolic | Cytochrome-c-oxidase, NADH fluorescence [5] | Multispectral imaging, fluorescence microscopy | Intrinsic contrast, exogenous dyes |

Fundamental Physical Principles of Light-Tissue Interaction

The effectiveness of different optical imaging modalities is largely determined by how light interacts with biological tissue. Two fundamental processes govern this interaction: absorption and scattering.

Absorption occurs when photons transfer their energy to molecules in the tissue, with hemoglobin being a dominant absorber in the brain. Critically, oxygenated hemoglobin (HbO) and deoxygenated hemoglobin (HbR) have distinct absorption spectra, particularly in the near-infrared range (700-900 nm). This spectral difference enables the quantification of relative changes in hemoglobin concentration through techniques like fNIRS [7] [5].

Scattering causes photons to deviate from their original path and represents the major obstacle to high-resolution deep tissue imaging. The degree of scattering is wavelength-dependent, with near-infrared light (700-900 nm) experiencing less scattering than visible light in neural tissue, creating an "optical window" for non-invasive imaging [7] [5].

The following diagram illustrates the fundamental principles of how different imaging modalities harness light-tissue interactions:

Figure 1: Fundamental principles of light-tissue interactions in optical brain imaging modalities

Detailed Modality Analysis

Near-Infrared Spectroscopy (NIRS) Platforms

Functional near-infrared spectroscopy (fNIRS) represents a cornerstone of non-invasive optical neuroimaging, particularly valuable for clinical populations and studies requiring naturalistic movement or portable monitoring solutions [6].

Technical Principles and Instrumentation

fNIRS operates on the principle that near-infrared light (700-900 nm) can penetrate biological tissues, including the scalp, skull, and brain, while being differentially absorbed by hemoglobin species. The modified Beer-Lambert law forms the mathematical foundation for relating changes in light attenuation to changes in hemoglobin concentration [7]:

Equation: OD = log(I₀/I) = ε · [X] · l · DPF + G

Where OD is optical density, I₀ and I are incident and detected light intensity, ε is extinction coefficient, [X] is chromophore concentration, l is source-detector separation, DPF is differential pathlength factor, and G is geometry-dependent factor [7].

Three primary fNIRS instrumentation approaches have been developed:

Continuous Wave (CW) Systems: Most common commercial systems using constant light intensity. Relatively simple and cost-effective but cannot provide absolute quantification of hemoglobin concentrations without additional pathlength modeling [7].

Frequency Domain (FD) Systems: Utilize amplitude-modulated light to directly measure photon pathlength, enabling absolute quantification of absorption and scattering coefficients [7].

Time Domain (TD) Systems: Employ short light pulses and time-of-flight measurements to directly resolve photon pathlength, offering the most comprehensive information but with greater technical complexity [7].

Experimental Protocol: fNIRS for Balance Task Monitoring

A representative fNIRS experimental protocol for studying cortical activation during balance tasks involves these key steps [6]:

Subject Preparation: Apply fNIRS head cap with source-detector array positioned over regions of interest (e.g., frontal, motor, sensory, temporal cortices) using International 10-20 system for registration.

System Setup: Configure continuous wave fNIRS instrument (e.g., TechEn CW6) with dual wavelengths (690 nm and 830 nm) and source-detector spacing of 3.2 cm to achieve appropriate penetration depth.

Data Acquisition: Record at 4 Hz sampling rate while subject performs balance tasks (e.g., Nintendo Wii Fit skiing simulation), with experimental paradigms typically structured as block designs with 30-second rest periods alternating with task periods.

Signal Processing: Convert raw light intensity measurements to optical density, then to hemoglobin concentration changes using modified Beer-Lambert law with appropriate differential pathlength factors.

Statistical Analysis: Apply general linear modeling to identify statistically significant hemodynamic responses correlated with task conditions, typically showing increased oxyhemoglobin and decreased deoxyhemoglobin in activated regions.

Two-Photon Microscopy

Two-photon laser scanning microscopy (TPLSM) represents the gold standard for high-resolution in vivo imaging in neuroscience, enabling visualization of cellular and subcellular structures in the living brain [8] [9].

Fundamental Principles and Advantages

The technique relies on the near-simultaneous absorption of two photons, each with approximately half the energy needed for electronic transition. This nonlinear process occurs only at the focal point where photon density is highest, providing inherent optical sectioning without the need for a confocal pinhole [8] [9].

Key advantages of two-photon microscopy include:

- Reduced scattering: Use of near-infrared excitation light (700-1000 nm) experiences less scattering in biological tissues [8]

- Deep tissue penetration: Enables imaging up to ~1 mm in neocortex, accessing cortical layers II/III and upper layer V [8]

- Minimal photodamage: Confined excitation volume reduces out-of-focus photobleaching and phototoxicity [9]

- Compatibility with diverse labels: Works with synthetic dyes, genetically encoded indicators, and fluorescent proteins [8]

The following diagram illustrates the experimental workflow for in vivo two-photon imaging:

Figure 2: Experimental workflow for in vivo two-photon microscopy in neuroscience research

Experimental Protocol: In Vivo Calcium Imaging

A standard protocol for two-photon calcium imaging of neuronal population activity includes [8]:

Cranial Window Installation: Under anesthesia, perform craniotomy over the region of interest (e.g., primary visual cortex) and implant a glass coverslip sealed with dental acrylic to create a stable optical window for chronic imaging.

Fluorescent Indicator Expression: Utilize one of several labeling approaches:

- Synthetic dyes: Bulk loading with AM-ester dyes (e.g., OGB-1 AM) using multicell bolus loading technique

- Genetically encoded indicators: Viral vector delivery (e.g., AAV-GCaMP) or transgenic mouse lines expressing calcium indicators under cell-type specific promoters

Two-Photon Microscope Setup: Configure laser-scanning microscope with tunable Ti:Sapphire laser (700-1000 nm range), high numerical aperture objective (20x-40x water immersion), and GaAsP photomultiplier tubes for high-sensitivity detection.

Image Acquisition: Collect time-series data at 4-30 Hz frame rate depending on field of view, with typical imaging volumes of 200×200×200 μm³ for population imaging or smaller fields for single-cell resolution.

Motion Correction and Signal Extraction: Apply computational algorithms to correct for brain motion artifacts, then extract fluorescence traces (ΔF/F) from regions of interest corresponding to individual neurons.

Data Analysis: Relate calcium transients to neuronal spiking activity, sensory stimuli, or behavioral parameters through correlation analysis and statistical modeling.

Emerging and Advanced Modalities

Shortwave Infrared (SWIR) Imaging Recent advances have extended fluorescence imaging into the shortwave infrared range (1000-1700 nm), which offers reduced scattering and autofluorescence compared to traditional NIR windows. SWIR imaging, enabled by novel emitters including organic dyes, quantum dots, and single-wall carbon nanotubes, provides improved tissue penetration and resolution for anatomical, dynamic, and molecular neuroimaging [12].

Multimodal and Optoacoustic Approaches Combining multiple imaging modalities addresses limitations of individual techniques. Functional optoacoustic neuro-tomography (FONT) with genetically encoded calcium indicators like NIR-GECO2G enables whole-brain distributed functional activity mapping with cellular specificity across large volumes [10]. This approach leverages the low vascular background and deep penetration of NIR light while providing ultrasound resolution.

Expansion Microscopy for Ultrastructural Context pan-ExM-t (pan-expansion microscopy of tissue) represents a revolutionary approach that combines ~16-24-fold physical expansion of brain tissue with fluorescent pan-staining of proteins and lipids [11]. This method provides electron microscopy-like ultrastructural context while maintaining molecular specificity through immunolabeling, enabling visualization of synaptic nanostructures including presynaptic dense projections and postsynaptic densities with standard confocal microscopes [11].

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential research reagents for in vivo optical brain imaging

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function/Application | Compatible Modalities |

|---|---|---|---|

| Genetically Encoded Calcium Indicators | GCaMP series, NIR-GECO2G [10] | Report neuronal activity via calcium concentration changes | Two-photon microscopy, optoacoustic tomography, widefield fluorescence |

| Synthetic Fluorescent Dyes | OGB-1 AM (calcium), sulforhodamine 101 (astrocytes) [8] | Cell labeling and functional imaging | Two-photon microscopy, widefield imaging |

| Voltage-Sensitive Dyes | RH795, Di-4-ANEPPS [5] | Report membrane potential changes | Macroscopic cortical imaging, two-photon microscopy |

| Fluorescent Proteins | GFP, RFP variants (e.g., tdTomato) [8] | Cell-type specific labeling, morphological analysis | Two-photon microscopy, expansion microscopy |

| Nanoparticle Contrast Agents | Quantum dots, single-wall carbon nanotubes [12] | Deep tissue imaging, SWIR contrast | SWIR imaging, optoacoustic tomography |

| pan-Staining Dyes | NHS ester dyes [11] | Bulk protein labeling for ultrastructural context | Expansion microscopy (pan-ExM-t) |

| Clinical Contrast Agents | Indocyanine green [12] | Vascular imaging, clinical applications | NIRS, diffuse optical tomography |

The landscape of in vivo optical imaging for neuroscience research encompasses a diverse and complementary set of technologies, each with distinct strengths and applications. From portable, non-invasive fNIRS for human studies to high-resolution two-photon microscopy for cellular investigation in animal models, these modalities collectively provide unprecedented access to brain structure and function across multiple spatial and temporal scales.

Current trends point toward continued technological refinement, including expansion into new spectral windows like SWIR, development of increasingly specific molecular probes, and integration of multiple modalities in hybrid approaches. These advances promise to further illuminate the complex dynamics of the living brain, accelerating both basic neuroscience discovery and therapeutic development for neurological disorders.

The optimal choice of imaging methodology depends critically on the specific research question, spatial and temporal resolution requirements, tissue depth of interest, and whether the application involves human subjects or animal models. As these technologies continue to evolve, they will undoubtedly remain indispensable tools in the neuroscientist's arsenal, providing unique windows into brain function in health and disease.

This technical guide explores the principles and applications of intrinsic contrast mechanisms for measuring hemodynamics and metabolism in living brains. Intrinsic contrast refers to the use of endogenous biological molecules that naturally interact with light or magnetic fields, enabling non-invasive or minimally invasive functional imaging. We focus on two primary endogenous contrast sources: hemoglobin for hemodynamic monitoring and cytochromes for metabolic activity assessment. This whitepaper details the underlying physics, instrumentation, experimental protocols, and data interpretation methods for researchers pursuing in vivo neuroscience studies and drug development applications.

Intrinsic contrast imaging leverages naturally occurring physiological contrasts rather than externally administered agents, providing unprecedented sensitivity to functional changes through endogenous biological signatures [13]. The fundamental advantage of this approach lies in its ability to monitor physiological processes without perturbing the system under investigation, making it particularly valuable for longitudinal studies and clinical applications.

In vivo optical brain imaging has seen 30 years of intense development, growing into a rich and diverse field that provides excellent sensitivity to functional changes through intrinsic contrast [13]. These techniques exploit the interaction of light with biological tissue at multiple wavelengths across the electromagnetic spectrum to retrieve physiological information, with the most significant advantages being excellent sensitivity to functional changes and the specificity of optical signatures to fundamental biological molecules [14].

The core physiological parameters measurable through intrinsic contrast include hemodynamic variables (blood volume, flow, oxygenation) and metabolic indicators (oxygen consumption, energy production). These measurements are particularly relevant for neuroscience research where understanding the coupling between neural activity, hemodynamics, and metabolism is essential for deciphering brain function in health and disease.

Physical Principles and Contrast Mechanisms

Light-Tissue Interactions

When light travels through biological tissue like the brain, it undergoes several interactions, with absorption and scattering being the two primary phenomena that generate intrinsic contrast [14]. Absorption by specific chromophores, particularly hemoglobin, provides the foundation for functional imaging, while scattering properties reveal structural information about the tissue microenvironment.

The absorption spectra of hemoglobin differ significantly between its oxygenated (HbO₂) and deoxygenated (HHb) states, enabling quantitative measurement of blood oxygenation through differential optical absorption [14]. This principle forms the basis for many intrinsic contrast imaging techniques, including hyperspectral imaging and near-infrared spectroscopy (NIRS).

Brain tissue exhibits relatively high transparency to light in the near-infrared (NIR) range between 650 and 1350 nm, a region known as the "optical window" [14]. This property enables non-invasive mapping of brain hemodynamics and functional activity, though depth penetration remains limited to superficial cortical layers in human applications due to scattering effects from extracerebral tissues (scalp and skull).

Hemodynamic Contrast Mechanisms

Hemodynamic intrinsic contrast primarily relies on the differential absorption properties of hemoglobin species. The molar absorption coefficients of HbO₂ and HHb vary significantly across the visible and NIR spectrum, with isosbestic points where their absorption is equal enabling concentration quantification [14].

The cerebral metabolic rate of oxygen (CMRO₂) can be estimated by combining hemoglobin concentration measurements with blood flow information, providing a crucial link between hemodynamics and metabolism [14]. This relationship forms the foundation for understanding neurovascular coupling and energy metabolism in the brain.

Table 1: Key Chromophores for Intrinsic Contrast Imaging

| Chromophore | Spectral Signature | Physiological Parameter | Measurement Technique |

|---|---|---|---|

| Oxy-hemoglobin (HbO₂) | Absorption peaks ~540, 580 nm; lower in NIR | Oxygen delivery, blood volume | Hyperspectral imaging, NIRS |

| Deoxy-hemoglobin (HHb) | Absorption peak ~555 nm; higher in NIR | Oxygen extraction, blood volume | Hyperspectral imaging, NIRS |

| Cytochrome c oxidase | Broad absorption in NIR | Mitochondrial metabolism, oxidative phosphorylation | Time-resolved spectroscopy |

| Water | Increasing absorption >900 nm | Tissue composition, edema | Multi-spectral imaging |

Metabolic Contrast Mechanisms

Beyond hemoglobin, intrinsic contrast can derive from molecules directly involved in cellular energy production. Cytochrome c oxidase, the terminal enzyme in the mitochondrial electron transport chain, has distinct optical absorption spectra that change with its oxidation state, providing a direct window into cellular metabolic activity [14].

The flavoprotein and NADH autofluorescence offers additional intrinsic contrasts for monitoring metabolic activity. These coenzymes involved in cellular respiration naturally fluoresce when excited with appropriate wavelengths, and their fluorescence intensity changes with metabolic state, enabling assessment of mitochondrial function and cellular energy production [14].

Imaging Modalities and Instrumentation

Hyperspectral Imaging (HSI)

Hyperspectral imaging (HSI) represents a powerful optical technology for biomedical applications that acquires two-dimensional images across a wide range of the electromagnetic spectrum [14]. HSI systems typically utilize very narrow and adjacent spectral bands over a continuous spectral range to reconstruct the spectrum of each pixel in the image, creating a three-dimensional dataset known as a hypercube (spatial x, y coordinates plus spectral information) [14].

The boundary between HSI and multispectral imaging (MSI) is not strictly defined, though HSI generally involves higher spectral sampling and resolution—typically below 10-20 nm—focusing on contiguous spectral bands rather than the discrete, relatively spaced bands characteristic of MSI [14]. This high spectral resolution enables precise identification and quantification of multiple chromophores simultaneously.

Table 2: Comparison of Intrinsic Contrast Imaging Modalities

| Modality | Spatial Resolution | Temporal Resolution | Depth Penetration | Primary Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hyperspectral Imaging | 10-100 μm | Seconds-minutes | ~1 mm (exposed cortex) | Hemoglobin mapping, CMRO₂ estimation |

| Multispectral Imaging | 10-100 μm | Seconds-minutes | ~1 mm (exposed cortex) | Hemoglobin oxygenation monitoring |

| Near-Infrared Spectroscopy (NIRS) | 1-10 cm | Seconds | Several cm | Non-invasive human brain monitoring |

| Functional MRI (BOLD) | 1-3 mm | Seconds | Whole brain | Human brain activation mapping |

| Intrinsic Signal Imaging | 10-100 μm | Seconds | ~1 mm | Cortical mapping in animal models |

Functional MRI with Endogenous Contrast

Blood oxygen level-dependent (BOLD) functional MRI represents another powerful intrinsic contrast technique that exploits magnetic properties of hemoglobin without exogenous contrast agents [15]. Deoxygenated hemoglobin is paramagnetic and creates magnetic field inhomogeneities that affect T2*-weighted MRI signals, while oxygenated hemoglobin is diamagnetic and has minimal effect [15]. Neural activation triggers localized increases in blood flow and oxygenation, reducing deoxyhemoglobin concentration and increasing MRI signal.

Arterial spin labeling (ASL) provides another endogenous contrast mechanism for MRI by magnetically labeling arterial water protons as an endogenous tracer to measure cerebral blood flow without exogenous contrast agents.

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Hyperspectral Imaging of Cerebral Hemodynamics

Materials and Equipment:

- Hyperspectral imaging system with appropriate spectral range (500-600 nm for visible; 650-950 nm for NIR)

- Surgical tools for cranial window preparation (for animal studies)

- Stereotaxic frame for head stabilization

- Physiological monitoring equipment (body temperature, respiration)

- Data acquisition computer with appropriate storage capacity

Procedure:

- Animal Preparation: Anesthetize the animal using appropriate anesthetic regimen (e.g., urethane for rodents). Maintain body temperature at 37°C using a heating pad. Secure animal in stereotaxic frame.

- Cranial Window Installation: Perform craniotomy over the region of interest. For chronic studies, utilize a thinned-skull preparation or implant a transparent cranial window. Keep the dura mater intact and moist with artificial cerebrospinal fluid.

- System Calibration: Perform dark current calibration by acquiring images with the lens covered. Acquire images of a standard reflectance target for flat-field correction.

- Baseline Image Acquisition: Acquire hyperspectral image cubes of the baseline state across the selected spectral range. Ensure adequate signal-to-noise ratio by appropriate integration time settings.

- Functional Stimulation: Apply the designed stimulus (sensory, electrical, pharmacological) while continuously acquiring hyperspectral data.

- Data Collection: Continue acquisition during stimulation and for an appropriate post-stimulus period to capture the hemodynamic response.

Data Analysis:

- Spectral Unmixing: Apply algorithms to decompose the measured spectra into contributions from HbO₂ and HHb using their known extinction coefficients.

- Concentration Calculation: Convert optical densities to concentration changes using the modified Beer-Lambert law.

- Spatio-temporal Mapping: Generate maps of HbO₂, HHb, and total hemoglobin changes over time.

- CMRO₂ Estimation: Calculate the cerebral metabolic rate of oxygen using Fick's principle, combining hemoglobin oxygenation data with blood flow information from laser speckle contrast imaging or other modalities.

BOLD fMRI for Human Brain Activation

Materials and Equipment:

- MRI scanner with field strength ≥3T for improved signal-to-noise ratio

- Head coil appropriate for the study

- Stimulus presentation system (visual, auditory, or other)

- Response recording devices (button boxes, etc.)

- Physiological monitoring equipment (pulse oximeter, respiratory belt)

Procedure:

- Subject Preparation: Screen subjects for MRI compatibility. Position subject in scanner with comfortable head immobilization using foam padding.

- Localizer Scans: Acquire structural localizer images for precise positioning of functional slices.

- BOLD Protocol Optimization: Select appropriate pulse sequence parameters (TR, TE, flip angle, resolution) to maximize BOLD sensitivity.

- Task Paradigm Design: Implement block design or event-related design with appropriate baseline conditions.

- Data Acquisition: Acquire T2*-weighted images during task performance with whole-brain coverage and adequate temporal resolution.

- Physiological Monitoring: Record cardiac and respiratory fluctuations concurrently with BOLD data acquisition.

Data Analysis:

- Preprocessing: Apply slice timing correction, head motion correction, spatial smoothing, and temporal filtering.

- Statistical Analysis: Use general linear model (GLM) to identify voxels showing significant signal changes correlated with the task paradigm.

- Group Analysis: Implement random effects analysis to draw population inferences.

- Activation Mapping: Overlay statistical maps on high-resolution anatomical images for visualization.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials for Intrinsic Contrast Experiments

| Item | Function | Example Applications | Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hyperspectral Imaging System | Acquires spatial and spectral data simultaneously | Hemoglobin mapping, oxygen metabolism | Spectral range, resolution, and acquisition speed must match application needs |

| MRI Scanner with BOLD Capabilities | Detects hemoglobin oxygenation changes | Human brain activation studies | Field strength directly impacts sensitivity and spatial resolution |

| Cranial Window Chambers | Provides optical access to the brain | Long-term cortical imaging in animal models | Biocompatibility, optical quality, and chronic stability are crucial |

| Physiological Monitoring System | Monitors vital signs during experiments | Ensuring physiological stability | Should include temperature, respiration, and cardiovascular monitoring |

| Spectral Analysis Software | Processes hyperspectral data cubes | Chromophore quantification, spectral unmixing | Algorithms for accurate separation of overlapping spectral signatures |

Visualization of Signaling Pathways and Workflows

Neurovascular Coupling Pathway

Hyperspectral Imaging Workflow

Applications in Neuroscience and Drug Development

Intrinsic contrast imaging techniques provide powerful tools for basic neuroscience research and pharmaceutical development. In basic research, these methods enable investigation of neurovascular coupling—the fundamental relationship between neural activity, hemodynamics, and metabolism [14]. This understanding is crucial for interpreting functional imaging signals and understanding brain energy metabolism.

In drug development, intrinsic contrast methods offer valuable biomarkers for assessing therapeutic efficacy and understanding drug mechanisms. The ability to repeatedly measure hemodynamic and metabolic parameters non-invasively makes these techniques ideal for longitudinal studies of disease progression and treatment response [16]. This is particularly relevant for neuropsychiatric disorders where heterogeneous patient populations and unreliable endpoints have hampered drug development [16].

Hyperspectral imaging solutions have shown particular promise for monitoring brain tissue metabolic and hemodynamic parameters in various pathological conditions, including neurodegenerative diseases and brain injuries [14]. The identification of irregular tissue functionality through metabolic imaging potentially enables early detection and intervention for neurological disorders.

Challenges and Future Perspectives

Despite significant advances, intrinsic contrast imaging faces several challenges. Depth penetration remains limited for optical techniques, particularly in non-invasive human applications where the scalp and skull significantly scatter light [14]. The development of advanced reconstruction algorithms and hybrid approaches combining multiple imaging modalities may help address these limitations.

Another challenge involves the quantitative interpretation of intrinsic contrast signals, particularly disentangling the complex relationships between neural activity, hemodynamics, and metabolism [14]. Computational models that incorporate known physiology can help derive more specific physiological parameters from the measured signals.

Future developments will likely focus on improving spatial and temporal resolution, developing more sophisticated analysis methods, and integrating multiple contrast mechanisms for comprehensive physiological assessment. The combination of intrinsic contrast with targeted extrinsic agents may provide the specificity needed for molecular imaging while maintaining the advantages of endogenous contrast for functional assessment.

For drug development, the adoption of standardized intrinsic contrast biomarkers could significantly improve patient stratification and target validation in clinical trials [16]. As these techniques become more widely available and better validated, they have the potential to transform neuroscience research and therapeutic development for neurological and psychiatric disorders.

In vivo neuroscience research has been fundamentally transformed by optical imaging technologies that bypass the limitations of traditional electrode-based methods. While techniques like whole-cell patch-clamp electrophysiology provide precise measurements, they are inherently low-throughput, typically enabling investigation of only one or a handful of cells simultaneously [17]. The need to observe signal transfer across complex neural circuits created demand for approaches capable of recording from hundreds of neurons simultaneously. Although calcium imaging addressed some of these needs by enabling simultaneous recording from tens to hundreds of cells, it provides only indirect readout of membrane potential changes, lacks temporal resolution for dissecting individual depolarization events at high spiking frequencies, and cannot report on hyperpolarizing or subthreshold membrane potential changes [17]. These limitations created the opportunity for optical electrophysiology using voltage-sensitive dyes (VSDs) and genetically encoded fluorescent reporters, which now enable direct observation of electrical activity across neuronal populations with millisecond precision.

Fundamental Principles and Mechanisms

Photophysical Mechanisms of Voltage Sensing

Voltage-sensitive dyes function by embedding within the cell membrane where they directly experience the uneven charge distribution across the phospholipid bilayer. The two primary classes of modern organic VSDs employ distinct mechanisms to transduce membrane potential changes into optical signals:

- Electrochromic Mechanism: Membrane potential changes induce a spectral shift through alteration of the dye's HOMO-LUMO gap, resulting in voltage-dependent spectral changes that can be measured as absorption or fluorescence shifts [17].

- Photoinduced Electron Transfer (PeT) Mechanism: Changes in membrane potential alter the probability of electron transfer from a π-wire module to the chromophore unit, leading to measurable changes in fluorescence quantum yield [17].

Table 1: Major Classes of Voltage-Sensitive Dyes and Their Properties

| Dye Class | Representative Dyes | Mechanism | Excitation/Emission | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Electrochromic | di-8-ANEPPS, di-4-ANEPPS | Spectral shift | Varies by specific dye | Fast response (<1 ms), rationetric capability [17] [18] |

| PeT-based | VoltageFluor (VF) series | Quantum yield change | Varies by specific dye | High brightness, improved targeting [17] |

| Styryl (Hemicyanine) | RH414, RH795, di-2-ANEPEQ | Multiple mechanisms | Visible spectrum | Widely used in embryonic CNS studies [19] |

| Merocyanine-rhodanine | NK2761 | Absorption change | ~703 nm | High signal-to-noise, low toxicity [19] |

Genetically Encoded Voltage Indicators (GEVIs)

In contrast to synthetic VSDs, genetically encoded voltage indicators are protein-based sensors derived from voltage-sensitive domains engineered to transform voltage responses into fluorescent signals. Early GEVI designs suffered from performance limitations, but recent developments have produced indicators with sufficient speed and sensitivity for in vivo applications [17] [20]. GEVIs typically employ either intrinsic fluorescence or coupling to fluorescent proteins/small-molecule fluorophores, enabling cell-type-specific expression through genetic targeting [20].

Figure 1: Fundamental operating principles of major voltage indicator classes

Experimental Methodologies and Protocols

Dye Loading and Tissue Preparation

Effective VSD imaging requires careful optimization of dye loading conditions and tissue preparation. For ex vivo brain slice preparations, the meningeal tissue is carefully removed to facilitate dye penetration [19]. Staining typically involves incubating tissue in physiological solution containing 0.04-0.2 mg/mL dye for 20 minutes, with the immature cellular-interstitial structure of embryonic tissue allowing better dye diffusion into deeper regions [19]. For in vivo applications, surgical preparation involves anesthetizing the animal, retracting the scalp, and thinning the skull over the region of interest. In some cases, a permanent cranial window can be implanted for repeated long-term imaging over periods exceeding one year [5].

Optical Imaging Hardware Configuration

Modern VSD imaging employs several specialized optical configurations optimized for different experimental needs:

- Epi-fluorescence Measurements: Use quasi-monochromatic light (510-560 nm excitation) reflected off a 575 nm dichroic mirror, with emission collected through a >590 nm long-pass filter [19].

- Ratiometric Measurements: Incorporate secondary dichroic beamsplitting and dual photodetectors (typically <570 nm and >570 nm) to detect voltage-dependent spectral shifts, enabling quantitative membrane potential determination with ~5 mV resolution without temporal or spatial averaging [18].

- High-Speed Imaging: Utilize CMOS-based cameras capable of recording at up to 1,923 frames per second at 256×256 pixel resolution to capture action potential propagation [21].

Table 2: Performance Characteristics of Selected Voltage-Sensitive Dyes

| Dye Name | Signal-to-Noise Ratio | Photobleaching Rate | Toxicity/Recovery | Recommended Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| di-2-ANEPEQ | Largest among fluorescence dyes | Faster | Slower neural response recovery | High-fidelity recording where toxicity is less concern [19] |

| di-4-ANEPPS | Large | Moderate | Relatively long recovery time | General purpose voltage imaging [19] |

| di-3-ANEPPDHQ | Large | Moderate | Relatively long recovery time | Embryonic CNS studies [19] |

| di-4-AN(F)EPPTEA | Smaller | Slower | Faster recovery | Long-duration experiments [19] |

| di-2-AN(F)EPPTEA | Smaller | Slower | Faster recovery | Chronic imaging preparations [19] |

| NK2761 (absorption) | High | Small | Low toxicity, fast recovery | Embryonic nervous system population recording [19] |

Data Acquisition and Analysis

Functional imaging experiments typically involve presenting carefully controlled stimuli (visual, somatosensory, or auditory) during image acquisition, with responses averaged over multiple repetitions to improve signal-to-noise ratio [5]. Data analysis incorporates spatial and temporal filtering to enhance signals, with visualization of spatiotemporal activity patterns through pseudocolor representations and waveform analysis [21]. For ratiometric measurements, calibration is achieved using simultaneous optical and patch-clamp recordings from adjacent points [18].

Figure 2: Standard workflow for voltage-sensitive dye imaging experiments

Advanced Targeting Strategies for Cell-Type-Specific Recording

Synthetic Dye Targeting Approaches

A significant limitation of early VSDs was their non-specific labeling of all membranes in complex tissue environments. Recent innovations have produced sophisticated targeting strategies:

- Enzymatic Uncaging: Polar groups (e.g., phosphate esters) solubilize VSD precursors until activated by cell-specifically expressed phosphatases or esterases [17].

- Light-Directed Activation: "SPOT" sensors remain inactive until triggered by 390 nm light irradiation in defined locations [17].

- Self-Labeling Protein Tags: Hybrid chemogenetic approaches utilize VSDs linked to reactive groups captured by cell-selectively expressed enzymes (HaloTag, SpyTag, ACP-Tag) [17].

- Ligand-Directed Delivery: The VoLDe platform combines dextran polysaccharide carriers with small molecule ligands for cell-selective targeting via natively expressed protein markers, enabling cell-type-specific voltage imaging without genetic manipulation [17].

Organelle-Specific Voltage Imaging

Beyond plasma membrane potential measurements, specialized approaches now enable voltage recording from intracellular compartments:

- Mitochondrial Voltage Imaging: Modern dyes with esterase-mediated unmasking enable specific mitochondrial membrane potential measurements [17].

- Voltair Nanodevices: Nucleic acid-based systems with PeT-based VSDs measure potential across endosomes, lysosomes, and trans-Golgi networks [17].

- LUnAR RhoVR: Tetrazine-substituted PeT sensors activated by click chemistry with trans-cyclooctene-functionalized ceramide in the endoplasmic reticulum [17].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Reagents and Equipment for Voltage-Sensitive Dye Imaging

| Category | Specific Examples | Function/Purpose | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Voltage-Sensitive Dyes | di-4-ANEPPS, di-2-ANEPEQ, RH795, VoltageFluor dyes | Report membrane potential changes | Selection depends on signal size, photobleaching, and toxicity requirements [19] |

| Genetically Encoded Indicators | GEVIs based on voltage-sensitive domains | Cell-type-specific voltage reporting | Enable targeting to specific neuronal populations [20] |

| Imaging Systems | MiCAM05-N256, THT Mesoscope, two-photon microscopes | High-speed optical recording | Frame rates >1,000 fps needed for action potential resolution [22] [21] |

| Light Sources | ZIVA Light Engine, Lumencor solid-state engines | Provide excitation illumination | Millisecond control for optogenetics compatibility [22] |

| Targeting Tools | HaloTag ligands, VoLDe platform components | Cell-specific dye delivery | Enable recording from defined cell populations [17] |

| Analysis Software | BV_Ana, BV Workbench | Processing optical recording data | Spatial/temporal filtering, waveform analysis [21] |

Current Applications and Future Directions

Voltage-sensitive dyes and fluorescent reporters now enable diverse neuroscience applications from fundamental circuit mapping to drug screening. In cardiac research, VSDs visualize action potential propagation in isolated hearts and cultured cardiomyocytes at frame rates exceeding 1,800 fps [21]. In developmental neuroscience, specific dyes like NK2761 permit functional organization analysis during embryogenesis [19]. For systems neuroscience, VSD imaging reveals spatiotemporal dynamics of sensory processing across cortical areas in response to visual, somatosensory, or auditory stimuli [5] [21].

The field continues to evolve with several promising directions:

- Improved Targeting Specificity: Advanced chemical and genetic targeting strategies will enable more precise recording from defined neuronal subpopulations [17] [23].

- Integration with Optogenetics: Combined optical stimulation and recording permits all-optical electrophysiology [22].

- Multiparametric Imaging: Simultaneous recording of membrane potential, calcium transients, and metabolic indicators provides comprehensive functional profiling [21].

- Clinical Translation: Fluorescence-guided interventions using optical contrast agents are emerging for intraoperative neural monitoring [24].

Despite these advances, challenges remain in achieving robust in vivo performance with synthetic VSDs in complex environments, improving signal-to-noise ratios without averaging, and minimizing phototoxicity during long-term imaging sessions. The ongoing development of both synthetic dyes and genetically encoded indicators suggests a future where these complementary approaches will continue to expand our ability to observe electrical activity throughout the nervous system with unprecedented spatial and temporal resolution.

The quest to understand the brain requires tools capable of mapping its intricate structures and dynamic processes at the appropriate scale. Emerging technologies in super-resolution microscopy and molecular probes are fundamentally transforming neuroscience research by enabling visualization of neural components and activities at unprecedented resolutions. These advancements are particularly crucial for bridging the gap between molecular mechanisms and systemic brain functions, providing researchers with powerful means to investigate neural circuitry, synaptic plasticity, and molecular dynamics in living systems. Framed within the broader context of in vivo techniques for neuroscience, these technologies offer unparalleled opportunities to observe biological processes in intact organisms, thereby accelerating both basic research and pharmaceutical development [25] [26]. The integration of advanced optical methods with specifically engineered molecular probes is creating new paradigms for investigating neural function and dysfunction, offering insights that were previously inaccessible through conventional microscopy approaches limited by the diffraction barrier of light.

Super-Resolution Microscopy: Seeing Beyond the Diffraction Limit

Fundamental Principles and Technique Comparisons

Super-resolution microscopy (SRM) encompasses several advanced optical techniques that overcome the diffraction limit of conventional light microscopy, which traditionally restricts resolution to approximately 200-300 nanometers laterally and 500-800 nanometers axially [27]. These methods have significantly narrowed the resolution gap between fluorescence microscopy and electron microscopy, opening new possibilities for biological discovery by enabling visualization of subcellular structures and molecular complexes at the nanoscale [27].

The table below provides a technical comparison of the four main categories of commercially available super-resolution microscopy techniques:

Table 1: Comparison of Major Super-Resolution Microscopy Techniques

| Technique (Variants) | Super-Resolution Principle | Spatial Resolution (Lateral) | Temporal Resolution | Key Applications in Neuroscience |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pixel Reassignment ISM (AiryScan, SoRA, iSIM) | Reduced Airy unit detection with mathematical or optical fluorescence reassignment | 140-180 nm (120-150 nm with deconvolution) | Low (single-point) to High (multi-point) | Live-cell imaging of synaptic vesicles, organelle dynamics |

| Structured Illumination Microscopy (SIM) (Linear SIM, SR-SIM) | Moiré interference from patterned illumination with computational reconstruction | 90-130 nm (down to 60 nm with deconvolution) | High (2D-SIM) to Intermediate (3D-SIM) | Neural cytoskeleton organization, nuclear architecture |

| Stimulated Emission Depletion (STED) | PSF reduction using excitation with doughnut-shaped depletion beam | ~50 nm (2D STED), ~100 nm (3D STED) | Variable (low for cell-sized FOV) | Nanoscale protein organization in synapses, membrane dynamics |

| Single-Molecule Localization Microscopy (SMLM) (STORM, PALM, PAINT) | Temporal separation of stochastic emissions with single-molecule positioning | ≥2× localization precision (10-20 nm typical) | Very low (typically fixed cells) | Molecular counting, protein complex organization |

Each technique offers distinct advantages and limitations, making them suitable for different neuroscience applications. STED and SMLM provide the highest spatial resolution but often at the cost of temporal resolution, while SIM and ISM offer better balance for live-cell imaging [27]. The choice of technique depends on specific experimental requirements including resolution needs, sample type, imaging depth, and live-cell compatibility.

Recent Technical Innovations

Recent advancements continue to push the boundaries of super-resolution imaging. A novel approach termed Confocal² Spinning-Disk Image Scanning Microscopy (C2SD-ISM) integrates a spinning-disk confocal microscope with a digital micromirror device (DMD) for sparse multifocal illumination [28]. This dual-confocal configuration achieves impressive lateral resolution of 144 nm and axial resolution of 351 nm while effectively mitigating scattering background interference, enabling high-fidelity imaging at depths up to 180 μm in tissue samples [28].

The C2SD-ISM system employs a dynamic pinhole array pixel reassignment (DPA-PR) algorithm that effectively corrects for Stokes shifts, optical aberrations, and other non-ideal conditions, achieving a linear correlation of up to 92% between original confocal and reconstructed images [28]. This high fidelity is crucial for quantitative analysis in neuroscience research where accurate representation of nanoscale structures is essential.

Table 2: Advanced Super-Resolution Implementation Considerations

| Parameter | Technical Challenges | Emerging Solutions |

|---|---|---|

| Imaging Depth | Scattering background interference in tissue | C2SD-ISM dual-confocal configuration; adaptive optics |

| Live-Cell Compatibility | Phototoxicity and photobleaching | Spinning-disk systems; reduced illumination intensity |

| Multicolor Imaging | Channel registration and chromatic aberration | Computational correction; optimized optical design |

| Throughput | Trade-off between resolution and acquisition speed | Multi-focal approaches; advanced detectors |

| Sample Preparation | Fluorophore compatibility and labeling density | Improved synthetic probes; genetic encoding |

For researchers without access to specialized SRM facilities, computational approaches like the Mean Shift Super-Resolution (MSSR) algorithm can enhance resolution from confocal microscopy images, though these must be applied cautiously as selection of thresholding parameters still depends on human visual perception [29].

Molecular Probes for Neuroscience

Optical Sensors for Neural Activity Monitoring

Molecular and chemical probes represent indispensable tools for modern neuroscience, with optical sensors enabling researchers to monitor neural activity with high spatiotemporal resolution. These tools have been particularly transformative for observing activity in large populations of neurons simultaneously, leveraging optical methods and genetic tools developed over the past two decades [25].

The two primary categories of optical sensors are:

- Chemical sensors that directly interact with specific ions or neurotransmitters

- Genetically encoded sensors that can be targeted to specific cell types or subcellular compartments based on genetic promoters

These optical sensors offer several advantages for neuroscience research. They can report sub-cellular dynamics in dendrites, spines, or axons; probe non-electrical facets of neural activity such as neurochemical and biochemical aspects of cellular activities; and densely sample cells within local microcircuits [25]. This dense sampling capability is particularly promising for revealing collective activity modes in local microcircuits that might be missed with sparser recording methods.

Genetic tools further enhance these capabilities by enabling targeting of specific cell types defined by genetic markers or connectivity patterns. Perhaps most importantly, they allow large-scale chronic recordings of identified cells or even individual synapses over weeks and months in live animals, which is especially beneficial for long-term studies of learning and memory, circuit plasticity, development, animal models of brain disease, and the sustained effects of candidate therapeutics [25].

Current Capabilities and Future Directions

Most current in vivo optical recordings focus on monitoring neuronal or glial calcium dynamics, as calcium indicators track action potentials as well as presynaptic and postsynaptic calcium signals at synapses, providing important information about both input and output signals [25]. However, significant limitations remain, as these indicators have variable ability to report subthreshold or inhibitory signals, and while existing indicators can achieve single-spike sensitivity in low firing rate regimes, they cannot yet faithfully follow spikes in fast-spiring neurons [25].

The future of this field lies not only in improving calcium sensors but in generating a broad suite of optical sensors. Voltage indicators are particularly ripe for development, as they could in principle follow both spikes and subthreshold signals, including inhibition [25]. While several genetically encoded voltage indicators have been developed, they do not yet have the desired combination of signal strength and speed. The experience gained from optimizing calcium indicators is expected to be directly applicable to improving voltage indicators, with particular emphasis on developing indicators with ultralow background emissions for reliable event detection and timing estimation [25].

Integrated Experimental Workflows

The power of super-resolution microscopy is fully realized when combined with appropriate molecular probes in integrated experimental workflows. The following diagram illustrates a generalized workflow for super-resolution imaging in neuroscience research, from sample preparation to data analysis:

Diagram 1: Super-resolution Imaging Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Successful implementation of super-resolution imaging in neuroscience requires careful selection of reagents and materials. The table below outlines key components of the research toolkit for these advanced applications:

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Super-Resolution Neuroscience

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function/Application | Technical Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fluorescent Probes | Synthetic dyes (ATTO, Cy dyes), FPs (GFP, RFP variants) | Target labeling for visualization | Photostability, brightness, switching characteristics |

| Immunolabeling Reagents | Primary/secondary antibodies, nanobodies | Specific protein targeting | Labeling density, specificity, accessibility |

| Genetic Encoders | Viral vectors (AAV, lentivirus), Cre-lox systems | Cell-type specific expression in model systems | Expression level, toxicity, delivery efficiency |

| Sample Preparation Materials | Fixatives, mounting media, coverslips | Sample preservation and optical properties | Refractive index matching, structural preservation |

| Imaging Buffers | STED depletion buffers, SMLM switching buffers | Control of fluorophore photophysics | Oxygen scavenging, thiol concentration, compatibility |

For studies focusing on functional imaging rather than structural analysis, molecular probes for monitoring neural activity are essential. The FLIPR Penta High-Throughput Cellular Screening System enables detailed studies of neural activity and disease mechanisms using human iPSC-derived models, which have become increasingly important for translational neuroscience [30]. These systems allow functional characterization of healthy and disease-specific neural models, such as Alzheimer's Disease (AD) organoids incorporating allelic variants of the ApoE gene (2/2, 3/4, and 4/4) to create disease-specific "neurospheres" [30].

Advanced three-dimensional neural organoids utilizing terminally differentiated iPSC-derived neural cells represent a groundbreaking cell-based assay platform with significant potential for neurotoxicity assessment, neuro-active effects of various neuromodulators, and disease modeling [30]. A critical feature of this platform is the use of kinetic calcium imaging, which provides reliable and accurate read-outs for functional neural activity, enabling evaluation of phenotypic changes and compound effects [30].

Applications in Drug Development and Neuroscience Research

Accelerating Pharmaceutical Development

The application of super-resolution microscopy and advanced molecular probes in pharmaceutical development has created significant opportunities for accelerating drug discovery pipelines. In vivo imaging techniques are recognized as valuable methods for providing biomarkers for target engagement, treatment response, safety, and mechanism of action [26]. These imaging biomarkers have the potential to inform the selection of drugs that are more likely to be safe and effective, potentially reducing the high attrition rates in late-phase clinical development where safety and lack of efficacy account for most failures [26].

A key advantage of in vivo imaging in pharmaceutical development is the ability to make repeated measurements in the same animal, significantly reducing the number of animals needed for preclinical studies while enhancing statistical power through intra-subject comparisons [26]. This aligns with the "3Rs" principle (Replacement, Reduction, and Refinement) in animal research, representing a more humane approach to pharmaceutical development [26].

Nuclear imaging techniques, particularly positron emission tomography (PET), have demonstrated significant utility in drug development. PET radionuclides such as 11C (20.4 min half-life) and 18F (109.7 min half-life) can be incorporated into drug candidates at high specific activities (1000-5000 Ci/mmol), enabling their injection at tracer levels (nmol injected) to measure biochemistry in vivo, especially at easily saturated sites like receptors [31]. The validation of receptor-binding radiotracers has been accelerated using gene-manipulated mice and liquid chromatography/mass spectrometry (LC/MS) to establish relevance to human metabolism and biodistribution [31].

Advancing Neuroscience Research

In basic neuroscience research, super-resolution techniques are enabling new discoveries about neural structure and function at the nanoscale. Recent studies have revealed:

- The functional diversity of over 40 different types of amacrine cells in the mouse retina [32]

- Both full-collapse fusion and the more transient 'kiss-and-run' fusion at hippocampal synapses, with the kiss-and-run form involving vesicle shrinkage between fusion events [32]

- How head-direction cells act as a stable 'neural compass' as bats navigate across large natural outdoor environments [32]

- That grid cells track a mouse's position in local reference frames instead of a global frame of reference during path integration tasks [32]

- How facial movements in mice provide a noninvasive readout of 'hidden' cognitive processes during decision-making [32]

These findings demonstrate how emerging mapping technologies are providing unprecedented insights into neural function across multiple scales, from molecular interactions to system-level processing.

The continuing evolution of super-resolution microscopy and molecular probes represents a transformative frontier in neuroscience research and drug development. These technologies are progressively breaking longstanding barriers in spatial and temporal resolution, while simultaneously improving compatibility with complex biological systems including living animals and human-derived models. The integration of advanced optical methods with specifically engineered molecular probes creates a powerful synergy that enables researchers to address fundamental questions in neuroscience with unprecedented precision.

As these technologies mature and become more accessible, they are poised to dramatically accelerate our understanding of brain function in health and disease. The ongoing development of improved voltage indicators, deeper tissue imaging capabilities, and more sophisticated computational analysis methods will further expand the applications of these approaches. For neuroscientists and drug development professionals, staying abreast of these rapidly advancing technologies is essential for leveraging their full potential in both basic research and therapeutic development.

From Bench to Bedside: Applications in Disease Research and Therapy

Exposed-cortex imaging represents a cornerstone of modern systems neuroscience, enabling researchers to visualize brain structure and function with exceptional resolution. This approach involves creating a cranial window or performing a craniotomy to allow optical access to the brain's surface and underlying structures, facilitating direct observation of neural activity in living animals. The development of exposed-cortex imaging techniques has been driven by the BRAIN Initiative's vision to generate a dynamic picture of the brain showing how individual cells and complex neural circuits interact at the speed of thought [33]. These methods have transitioned neuroscience from purely observational science to a causal, experimental discipline where researchers can not only monitor but also precisely manipulate neural circuit dynamics.

The fundamental advantage of exposed-cortex imaging lies in its ability to bypass the light-scattering properties of the skull, which significantly degrade image quality and resolution. Unlike non-invasive approaches that image through the skull, exposed-cortex techniques provide unobstructed optical access to neural tissues, enabling researchers to achieve cellular and even sub-cellular resolution while maintaining the brain's physiological integrity. This technical guide explores the core methodologies, applications, and quantitative comparisons of exposed-cortex imaging platforms, providing neuroscience researchers and drug development professionals with essential information for implementing these transformative technologies.

Core Imaging Modalities and Technical Specifications

Comparative Analysis of Exposed-Cortex Imaging Techniques

Table 1: Technical specifications and applications of major exposed-cortex imaging modalities

| Imaging Modality | Spatial Resolution | Temporal Resolution | Imaging Depth | Primary Applications | Key Advantages |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intrinsic Signal Imaging | 200-250 μm FWHM [34] | Seconds (hemodynamic-limited) [34] | Surface cortex | Mapping functional organizations (retinotopy, orientation) [34] | Non-invasive, wide-field, no indicators required |

| Two-Photon Microscopy | Sub-micron | Sub-second to seconds | ~400 μm [35] | Cellular & subcellular imaging, calcium dynamics [35] | High resolution, reduced phototoxicity, deep tissue imaging |

| Wide-Field Calcium Imaging | ~20 μm | Sub-second | Surface cortex | Large-scale network activity monitoring [34] | High speed, large field of view, genetically encoded indicators |

| Direct Electrocortical Stimulation (DECS) | 1-10 mm | Milliseconds | Direct surface contact | Functional mapping for surgical planning [36] | Gold standard for functional localization |

Performance Metrics and Quantitative Comparisons

Recent advances have enabled direct quantitative comparisons between exposed-cortex imaging and less-invasive approaches. The SeeThrough skull-clearing technique, developed through systematic screening of over 1,600 chemicals, represents a hybrid approach that achieves refractive index matching (RI = 1.56) while maintaining biocompatibility [35]. When compared to traditional open-skull cranial windows, SeeThrough provides equivalent imaging sensitivity and contrast for monitoring neuronal activity, including calcium transients in dendritic branches with comparable signal-to-noise ratios [35]. This demonstrates that under optimal conditions, minimally invasive methods can approach the performance of exposed-cortex preparations while better preserving brain physiology.

For functional mapping applications, quantitative comparisons reveal important methodological differences. Studies comparing task-based fMRI, resting-state fMRI, and anatomical MRI for locating hand motor areas found substantial variations (>20 mm) in determined locations across modalities in 52-64% of cases [37]. These discrepancies highlight the critical importance of selecting appropriate imaging techniques based on specific research questions and the continued value of direct cortical approaches for precise functional localization.

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Surgical Preparation for Chronic Cranial Window Implantation

The foundation of successful exposed-cortex imaging begins with precise surgical preparation. The following protocol outlines the key steps for creating a chronic cranial window preparation suitable for long-term neuronal imaging: