Environmental Enrichment and Neural Plasticity: A Comparative Analysis of Mechanisms and Therapeutic Applications

This article provides a comprehensive comparative analysis of environmental enrichment (EE) and its profound impact on neural plasticity, tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals.

Environmental Enrichment and Neural Plasticity: A Comparative Analysis of Mechanisms and Therapeutic Applications

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive comparative analysis of environmental enrichment (EE) and its profound impact on neural plasticity, tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals. We explore the foundational neurobiological mechanisms through which complex stimulation enhances brain resilience and repair. The scope extends to methodological applications of EE and emerging 'enviromimetic' therapeutics in preclinical and clinical models of neurological and psychiatric disorders, including stroke, Alzheimer's, and depression. The analysis also addresses critical challenges in protocol standardization, optimization, and translation. Finally, we present a rigorous validation and comparative framework, contrasting EE with pharmacological plasticity-promoters like psychedelics and ketamine, to illuminate shared pathways and unique therapeutic niches for future biomedicine.

Unraveling the Neurobiology: How Environmental Stimulation Shapes Brain Plasticity

In the realm of biomedical research, the housing conditions of laboratory animals represent a critical variable that significantly influences experimental outcomes, particularly in studies of neural plasticity. Standard laboratory housing is characterized by cages designed primarily for easy maintenance and hygiene, typically providing adequate basic physiological requirements but offering limited opportunities for sensory stimulation, physical activity, or cognitive challenges [1]. This conventional approach to animal housing has drawn increasing scrutiny as evidence mounts regarding its impact on both animal welfare and scientific validity.

Environmental enrichment (EE) has emerged as a systematic alternative to standard housing, defined as a housing condition that extends beyond basic welfare requirements to provide complex sensory, motor, cognitive, and social stimulation conducive to natural behaviors [2]. The conceptual foundation for EE traces back to pioneering work by Donald Hebb, who first observed that pet rats reared in stimulating home environments demonstrated superior learning abilities and problem-solving skills compared to their laboratory-housed counterparts [1]. This initial observation was later substantiated by Marian Diamond's groundbreaking neuroanatomical research in the 1960s, which provided tangible evidence of experience-dependent neuroplasticity by demonstrating physical changes in the cerebral cortex of rats exposed to novel and complex environments [3].

This comparative analysis examines the defining characteristics of environmental enrichment against standard laboratory housing, with a specific focus on implications for neural plasticity research. By synthesizing current evidence across multiple experimental models, we provide researchers with a framework for evaluating enrichment protocols that balance scientific rigor with enhanced animal welfare.

Defining Environmental Enrichment: Core Components and Principles

Environmental enrichment represents a multifaceted approach to laboratory animal housing that incorporates several core components. According to current definitions, EE aims to enhance animal well-being by providing sensory and motor stimulation through structures and resources that facilitate species-typical behaviors and promote psychological well-being [1]. This is achieved through the thoughtful inclusion of both social and non-social features to the cage environment, with the primary goal of improving welfare through physical and psychological stimulation [4].

The core components of effective environmental enrichment protocols include:

- Social enrichment: Housing social species in stable groups to allow for conspecific interaction, or alternatively, implementing positive reinforcement training to facilitate human-animal interaction [1].

- Physical enrichment: Structural modifications including larger cages or increased floor space, along with the addition of objects that encourage exercise, exploration, and manipulation [1].

- Sensory enrichment: Provision of varied visual, auditory, tactile, and olfactory stimuli that engage the animals' sensory capabilities without causing distress [2].

- Cognitive enrichment: Introduction of challenges that require problem-solving, learning, or memory, such as puzzle feeders or novel object recognition tasks [2].

- Nutritional enrichment: Implementation of varied feeding strategies that stimulate natural foraging behaviors, such as scattered food or food puzzles [1].

Taylor et al. have further described four hierarchical levels of environmental enrichment: (1) pseudo-enrichment that provides no biological benefit; (2) enrichment meeting basic needs; (3) enrichment providing hedonistic experiences; and (4) enrichment producing long-term accumulative benefits on physical and mental health, including stress resilience and adaptability [1]. This classification system helps researchers implement appropriately targeted enrichment strategies based on specific experimental objectives.

Table 1: Core Components of Environmental Enrichment Protocols

| Component | Definition | Example Implementations |

|---|---|---|

| Social Enrichment | Opportunities for interaction with conspecifics or humans | Group housing, positive reinforcement training, stable social hierarchies |

| Physical Enrichment | Structural modifications and objects that encourage activity | Larger enclosures, running wheels, tunnels, platforms, climbing structures |

| Sensory Enrichment | Stimulation of multiple sensory modalities | Novel objects, mirrored surfaces, varied bedding materials, auditory stimuli |

| Cognitive Enrichment | Challenges requiring problem-solving or learning | Puzzle feeders, maze tasks, novel object recognition tests |

| Nutritional Enrichment | Feeding strategies that promote natural foraging behaviors | Scattered feeding, food puzzles, varied treat items |

Comparative Analysis: Standard Housing Versus Enriched Environments

The distinction between standard housing and enriched environments extends far beyond simple cage decorations, representing fundamental differences in both philosophy and practical implementation. Standard housing for laboratory rodents typically consists of relatively small, barren cages with only absorbent bedding on the floor and ad libitum access to food and water [1]. While meeting basic physiological needs, this environment is characterized by monotony, limited sensory input, restricted movement opportunities, and minimal cognitive challenges – conditions that fail to accommodate the natural behavioral repertoire of the species [1].

In contrast, enriched environments are specifically designed to promote structural and functional development of the brain while enhancing cognitive behavioral performance through increased sensory, motor, cognitive, and social stimulation [2]. The Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals formally defines EE as aiming to "enhance animal well-being by providing animals with sensory and motor stimulation, through structures and resources that facilitate the expression of species-typical behaviors and promote psychological well-being" [1].

The behavioral manifestations of these housing differences are significant. Animals in standard housing frequently develop abnormal repetitive behaviors – such as excessive grooming, bar biting, circling, and back-flipping – associated with poor environmental and cognitive stimulation [1]. Conversely, rodents reared in enriched environments demonstrate increased behavioral diversity, reduced anxiety-like behaviors, enhanced exploratory tendencies, and improved coping abilities when facing challenges [1]. These behavioral differences reflect underlying neurobiological changes that have profound implications for research outcomes, particularly in neuroscience and pharmacological studies.

Table 2: Comparative Analysis of Housing Conditions

| Parameter | Standard Housing | Enriched Environment |

|---|---|---|

| Space Complexity | Minimal floor space with limited structural complexity | Increased floor space with multi-level structures, hiding places |

| Sensory Stimulation | Limited, monotonous sensory input | Varied, rotating sensory stimuli across multiple modalities |

| Social Structure | Often individual housing or unstable groups | Stable social groups appropriate to species biology |

| Behavioral Outcomes | Increased stereotypic behaviors, anxiety-like responses | Enhanced exploratory behavior, reduced anxiety, increased behavioral diversity |

| Cognitive Engagement | Minimal cognitive challenges | Regular opportunities for problem-solving and learning |

| Physical Activity | Restricted movement opportunities | Encouraged through wheels, climbing structures, and complex environments |

Effects on Neural Plasticity: Mechanisms and Experimental Evidence

Neuroanatomical and Molecular Changes

The impact of environmental enrichment on neural plasticity is well-documented across multiple experimental models. At the neuroanatomical level, EE produces measurable changes in brain structure, including increased cortical thickness, particularly in the occipital cortex [5]. These macroscopic changes reflect underlying cellular modifications, including increases in the size of neuronal cell bodies and nuclei, enhanced dendritic branching and complexity, increased synaptic density, and greater dendritic spine numbers [5]. Environmental enrichment also promotes neurovascular changes, including increased numbers of blood capillaries in the brain and enhanced metabolic activity evidenced by elevated mitochondrial numbers [5].

At the molecular level, EE modulates key signaling pathways implicated in neuroprotection and synaptic plasticity. Research has identified modulation of extracellular regulated kinase 1/2 (ERK1/2), mitogen-activated protein kinases (MAPK), and AMPK/SIRT1 pathways as central to the effects of environmental enrichment [2]. These pathways converge on critical molecular mediators of neural plasticity, particularly brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF), which shows elevated expression in enriched animals [3]. Additionally, EE induces epigenetic modifications through regulation of TET family proteins (TET1, TET2, and TET3), which affect DNA methylation levels and subsequently influence memory formation, hippocampal neurogenesis, and cognitive function [2].

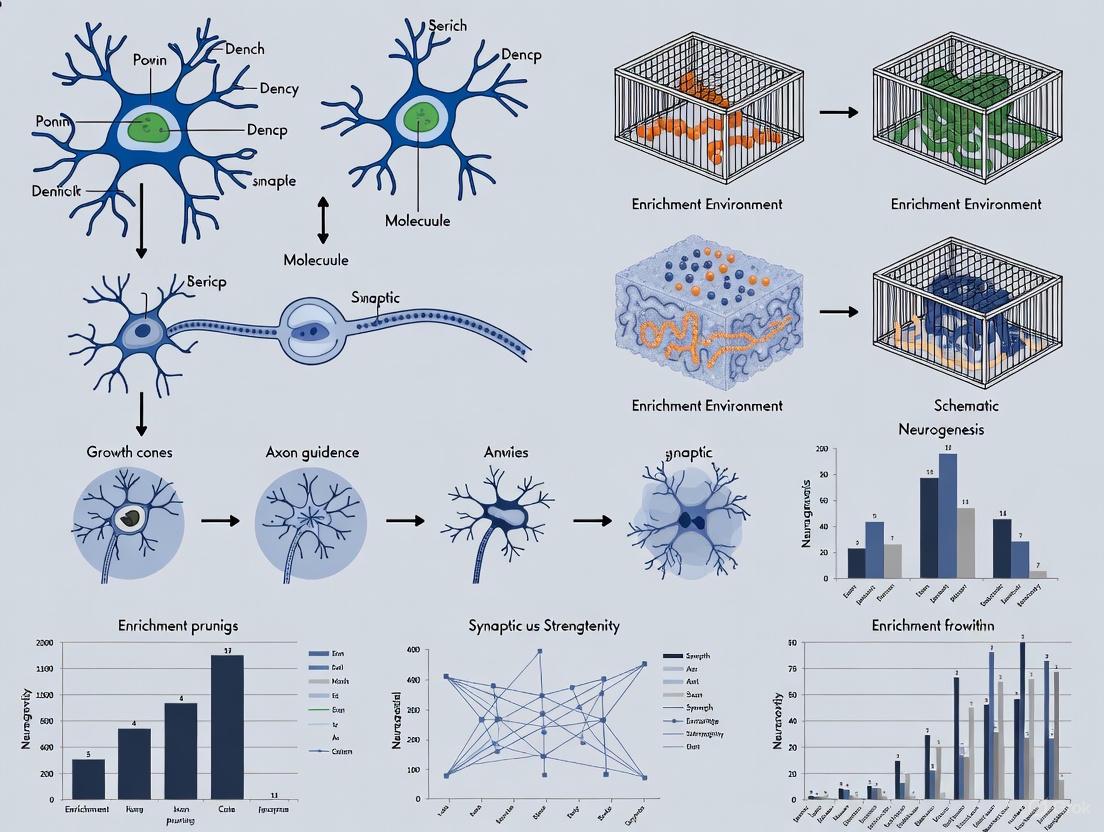

Diagram 1: EE-Induced Neural Plasticity Mechanisms (13 words)

Cognitive and Behavioral Outcomes

The neurobiological changes induced by environmental enrichment translate into significant functional improvements in cognitive and behavioral domains. Enriched animals demonstrate superior performance in various learning paradigms, including spatial navigation tasks such as the Morris Water Maze, where they exhibit more efficient acquisition and enhanced memory retention [5]. This learning enhancement appears to stem from multiple factors, including rapid information acquisition, flexible use of spatial information, and improved memory consolidation processes [5].

Environmental enrichment also reduces impulsive behaviors across species, with enriched animals demonstrating greater inhibitory control in tasks requiring delayed gratification [5]. This behavioral modulation has important implications for modeling human conditions characterized by impulsivity, including attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) and substance use disorders [5]. The anti-impulsivity effects of EE may underlie observations that enriched rats show reduced self-administration of various drugs of abuse, including amphetamines, nicotine, and alcohol [5].

Notably, these cognitive and behavioral benefits extend to clinical populations. A recent systematic review and meta-analysis of infants with or at high risk of cerebral palsy demonstrated that EE interventions significantly improved motor development, gross motor function, and cognitive development [6]. Subgroup analyses further identified optimal age windows for these interventions, with 6-18 months being most effective for motor development and 6-12 months for cognitive development [6].

Experimental Protocols and Methodological Considerations

Standardized Enrichment Protocols

Implementing environmental enrichment in research settings requires careful consideration of species-specific needs and experimental requirements. For laboratory rodents, a typical EE protocol involves housing animals in larger cages (approximately 60 × 40 × 20 cm for mice; 100 × 50 × 50 cm for rats) containing various objects that are rearranged and partially replaced with novel items 2-3 times per week to maintain novelty and prevent habituation [1]. Social housing with stable group compositions is standard, typically containing 8-12 animals per enriched cage [1].

The duration of enrichment exposure varies significantly across studies, with systematic reviews indicating that most protocols last between 1-6 weeks [1]. Approximately 30% of rodent enrichment studies expose animals during the 41-90 postnatal day period, while another significant proportion begins enrichment immediately after weaning (postnatal day 21) [1]. The timing and duration of EE exposure represent critical methodological considerations, as effects demonstrate both age sensitivity and exposure duration dependence.

For large animal models and clinical applications, EE protocols are adapted to species-specific characteristics while maintaining the core principles of complexity, novelty, and engagement. In infant human populations, EE interventions such as COPCA (Coping with and Caring for Infants with Special Needs), GAME (Goals-Activity-Motor-Enrichment), and SPEEDI (Supporting Play Exploration and Early Development Intervention) have been developed and validated, emphasizing play-based environmental stimulation combined with active social interaction with caregivers or healthcare professionals [6].

Methodological Considerations for Research

The implementation of environmental enrichment in research settings requires careful attention to several methodological considerations:

- Strain and sex differences: Responses to EE demonstrate significant variation across different rodent strains and between sexes, necessitating careful experimental design and reporting [4] [1].

- Temporal factors: The timing of enrichment initiation, duration of exposure, and age of subjects all influence outcomes, with critical periods of heightened sensitivity identified for specific cognitive domains [6].

- Standardization challenges: While concerns have been raised that EE might increase variability in experimental endpoints, empirical evidence suggests this concern may be unfounded, with no significant differences in coefficients of variation across housing conditions reported for measures of behavior, growth, or stress physiology [3].

- Interaction with experimental manipulations: EE can modify responses to various experimental interventions, including brain injuries, pharmacological treatments, and genetic manipulations, potentially enhancing translational validity but requiring careful interpretation [3].

Diagram 2: Key Experimental Design Considerations (10 words)

The Researcher's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

Implementing robust environmental enrichment protocols requires specific materials tailored to species-specific needs and research objectives. The following table details essential components for rodent enrichment protocols, though applications in other species would require appropriate adaptations.

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Environmental Enrichment

| Item Category | Specific Examples | Research Function | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nesting Materials | Paper strips, cotton fiber, wood wool, commercially available Nestlets | Promotes species-typical nest building behavior; provides thermal regulation and security | Material preference varies by strain; some materials may confound specific studies (e.g., allergy models) |

| Shelters/Hideaways | Plastic tunnels, wooden houses, cardboard tubes, inverted plastic containers | Provides security and retreat spaces; reduces stress through environmental control | Multiple entry points may reduce aggression; material composition affects preference and durability |

| Manipulative Objects | Wooden blocks, plastic toys, rubber items, bones/chews | Encourages exploration and manipulation; addresses gnawing needs for dental health | Objects should be rotated regularly to maintain novelty; size appropriate to prevent ingestion |

| Physical Activity Equipment | Running wheels, climbing platforms, ladders, ropes, swings | Promotes physical activity and motor skill development; enhances cardiovascular health | Voluntary use preferred; forced exercise represents a different experimental intervention |

| Foraging Enhancement | Puzzle feeders, scattered food items, treat-dispensing devices | Stimulates natural foraging behaviors; provides cognitive challenge | Nutritional content must be accounted for in dietary studies; caloric intake monitoring essential |

| SSR128129E | SSR128129E, MF:C18H15N2NaO4, MW:346.3 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

| Akn-028 | Akn-028, CAS:1175017-90-9, MF:C17H14N6, MW:302.33 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

The comparative analysis of environmental enrichment against standard laboratory housing reveals profound differences that extend beyond animal welfare to impact experimental outcomes and translational validity. Environmental enrichment represents a complex, multifactorial intervention that induces significant changes in neurobiology, behavior, and cognitive function through mechanisms involving enhanced neural plasticity, reduced impulsivity, and improved stress resilience.

For researchers in neuroscience and drug development, these findings carry important implications. First, the housing conditions of laboratory animals must be recognized as a significant variable affecting experimental outcomes, particularly in studies of neural function, behavior, and drug efficacy. Second, environmental enrichment offers a valuable tool for enhancing the translational validity of animal models, as enriched animals may better represent the complex sensory and cognitive environments of human populations. Third, standardization of enrichment protocols across laboratories will be essential for improving reproducibility while maintaining the welfare benefits of EE.

As research continues to elucidate the mechanisms underlying enrichment effects, particularly the molecular pathways and epigenetic modifications involved, opportunities emerge for developing "enviromimetics" – pharmacological interventions that mimic or enhance the beneficial effects of environmental enrichment [3]. Such approaches may be particularly valuable for clinical populations where comprehensive environmental modification is impractical.

The transition from standard housing to enriched environments represents both an ethical imperative and a scientific opportunity. By embracing complexity and species-appropriate housing, researchers can enhance both animal welfare and the quality and translational potential of their scientific findings.

The adult brain possesses a remarkable capacity for change, a phenomenon known as neural plasticity. This plasticity is driven by fundamental cellular processes, including the growth and branching of dendrites (dendritic arborization), the formation of new connections between neurons (synaptogenesis), and the birth of new neurons (neurogenesis). Once believed to be a static organ, the brain is now understood to be highly dynamic, with its circuitry being continuously refined by experience. Environmental enrichment (EE)—a paradigm providing complex sensory, motor, and social stimulation—serves as a powerful experimental tool to probe the limits of this plasticity. This guide provides a comparative analysis of how different enrichment strategies influence these core mechanisms, offering a structured overview of experimental data, protocols, and key reagents for researchers and drug development professionals.

Comparative Experimental Data on Enrichment Effects

Research across diverse models demonstrates that enrichment protocols consistently enhance markers of neural plasticity. The table below summarizes quantitative findings from key studies, illustrating the effects of various enrichment paradigms on dendritic complexity, synapse formation, and adult neurogenesis.

Table 1: Quantitative Effects of Environmental Enrichment on Measures of Neural Plasticity

| Experimental Model | Enrichment Paradigm | Effect on Dendritic Arborization | Effect on Synaptogenesis / Markers | Effect on Neurogenesis | Primary Experimental Evidence |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Healthy Rodents [7] | Combination of complex inanimate and social stimulation (Classic EE) | ↑ Dendritic length and spine density in frontal and parietal pyramidal neurons [7] | Synaptogenesis; ↑ levels of BDNF in the hippocampus and cerebellum [7] | Increased hippocampal neurogenesis [7] [8] | Morphometric analysis, immunohistochemistry, behavioral tasks (MWM, RAM) |

| Spinal Cord Injury (Mouse Model) [9] | EE housing (larger cage, novel objects, nesting material) for ≥10 days before injury | Enhanced regeneration of sensory axons in the dorsal columns in vivo [9] | Increased H3K27 and H4K8 histone acetylation in DRG neurons; mediated by Cbp [9] | Not explicitly measured | RNA-seq, histone modification analysis, chemogenetics, locomotor recovery tests |

| Synchronized hPSC-Derived Human Cortical Neurons [10] | N/A (Study of cell-intrinsic maturation) | Significant increase in total neurite length and complexity from day 25 to day 100 in vitro [10] | Progressive localization of SYN1 in presynaptic puncta; appearance of mEPSCs [10] | N/A (Model of post-mitotic neuronal maturation) | Long-term morphometric tracking, electrophysiology, scRNA-seq, ATAC-seq |

Key Insights from Comparative Data:

- Paradigm Efficacy: Complex EE, combining physical activity, cognitive stimulation, and social interaction, produces the most robust and widespread effects on plasticity across multiple brain regions [7].

- Timing and Duration: The duration of enrichment is critical. In spinal cord injury models, at least 10 days of pre-injury EE were required to induce a long-lasting pro-regenerative state in neurons [9].

- Species-Specific Dynamics: The timeline of neuronal maturation, including dendritic arborization and synaptogenesis, is intrinsically programmed and notably protracted in human neurons compared to rodents, a finding critical for translational research [10].

Detailed Experimental Protocols

To ensure reproducibility and facilitate the design of comparative studies, below are detailed methodologies for key protocols cited in the literature.

Standardized Environmental Enrichment (EE) Protocol for Rodents

This protocol is adapted from classic and contemporary studies to investigate experience-dependent plasticity [7] [8].

- Objective: To model a cognitively and physically stimulating lifestyle in a laboratory setting and assess its impact on neural plasticity.

- Materials:

- Large rodent cages (e.g., significantly larger than standard housing).

- Procedure:

- Housing: House rodents in groups (e.g., 8-12 per cage) to facilitate social interaction.

- Environmental Complexity: Equip the cage with a variety of non-chewable, novel objects (e.g., tunnels, ramps, platforms, Lego blocks) made of diverse materials (plastic, wood, metal).

- Cognitive Stimulation: Change and rearrange a portion of the objects in the cage 2-3 times per week to maintain novelty and cognitive challenge.

- Physical Activity: Provide unrestricted access to running wheels to encourage voluntary exercise.

- Duration: The intervention typically lasts from several weeks to months, depending on the research question. Control groups are housed in standard laboratory cages.

- Outcome Measures:

- Structural Plasticity: Histological analysis of dendritic spine density (e.g., Golgi-Cox staining), synaptophysin puncta, and BrdU/DCX staining for newborn neurons [11] [7].

- Molecular Plasticity: Western blot or ELISA for neurotrophic factors (e.g., BDNF); RNA sequencing for transcriptional changes [7] [9].

- Functional Recovery: In disease models, behavioral tests (e.g., BMS score for SCI, Morris Water Maze for memory) are used to assess functional outcomes [9].

Protocol for Synchronized Differentiation of Human Cortical Neurons

This protocol, based on recent work, allows for the precise study of intrinsic human neuronal maturation timelines, free from confounding ongoing neurogenesis [10].

- Objective: To generate a homogeneous, temporally synchronized population of human cortical neurons from pluripotent stem cells (hPSCs) for studying dendritic arborization and synaptogenesis.

- Materials:

- Human Pluripotent Stem Cells (hPSCs).

- Procedure:

- Neural Induction: Differentiate hPSCs into cortical neural precursor cells (NPCs) using dual SMAD inhibition (e.g., LDN-193189, SB431542) and WNT inhibition (e.g., IWR-1-endo) over ~20 days.

- Synchronization: At day 20, replate the homogeneous NPCs at an optimized density and treat with a Notch signaling inhibitor (e.g., DAPT, 10 µM) for 4-5 days. This forces nearly all NPCs to exit the cell cycle simultaneously.

- Maturation: Maintain the resulting post-mitotic neurons in culture for up to 100+ days, feeding with appropriate neuronal maturation media.

- Outcome Measures:

- Morphometric Analysis: Track neurite outgrowth and branching complexity over time using immunostaining for MAP2 and high-content image analysis [10].

- Electrophysiology: Perform whole-cell patch-clamp recordings at multiple time points to document the development of passive membrane properties, action potentials, and synaptic activity (mEPSCs) [10].

- Molecular Profiling: Use RNA-seq and ATAC-seq at serial time points (e.g., d25, d50, d75, d100) to map the gradual unfolding of transcriptional and epigenetic maturation programs [10].

Signaling Pathways in Neural Plasticity

Environmental enrichment and intrinsic genetic programs activate specific molecular pathways that converge to promote dendritic growth, synapse formation, and neurogenesis. The diagram below illustrates the core signaling machinery that integrates external stimuli with cellular changes.

Diagram Title: Key Signaling Pathways Regulating Experience-Dependent Neural Plasticity

Diagram Interpretation: This diagram synthesizes mechanisms by which environmental enrichment (EE) enhances plasticity. EE increases levels of neurotrophins like BDNF and activates epigenetic regulators like CBP, which acetylates histones (H3K27ac) to open chromatin and promote gene expression [7] [9]. These signals activate key pathways (PI3K/Akt, SIRT1, Wnt/β-catenin) that collectively drive neurogenesis, dendritic arborization, and synaptogenesis [12] [13]. Conversely, an intrinsic "epigenetic barrier" composed of factors like EZH2, EHMT1/2, and DOT1L represses these maturation programs, setting the protracted timeline for human neuronal development [10]. Inhibition of these repressors can precociously enhance maturation.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents

The following table catalogues essential reagents and their applications for investigating the core mechanisms of neural plasticity.

Table 2: Essential Reagents for Studying Neural Plasticity Mechanisms

| Reagent / Tool | Function / Target | Key Application in Research |

|---|---|---|

| Bromodeoxyuridine (BrdU) [11] | Synthetic thymidine analog incorporated into DNA during S-phase. | Birth-dating and quantification of newly generated cells in neurogenic niches (e.g., SGZ, SVZ). |

| Doublecortin (DCX) Antibodies [11] [14] | Immunohistochemical marker for immature neuronal cells and neuroblasts. | Labeling and tracking of newborn, migrating neurons in adult neurogenesis. |

| DAPT (γ-Secretase Inhibitor) [10] | Potent inhibitor of Notch signaling pathway. | Synchronizing neuronal differentiation in vitro by forcing neural precursor cells to exit the cell cycle. |

| CSP-TTK21 [9] | Activator of the lysine acetyltransferase CBP. | Mimicking the pro-regenerative effects of EE by increasing histone acetylation (H3K27ac, H4K8ac) and promoting axon regeneration. |

| Recombinant BDNF [7] [12] | Exogenous brain-derived neurotrophic factor. | Directly activating TrkB receptor signaling to promote neuronal survival, dendritic growth, and synaptogenesis in cell cultures. |

| K252a | Inhibitor of Trk receptor tyrosine kinases (including BDNF receptor TrkB). | Used to block BDNF/TrkB signaling to establish its necessity in observed plasticity phenomena. |

| Retrovirus (e.g., GFP-expressing) [11] | Engineered virus that infects dividing cells and integrates into the host genome. | Specific labeling and lineage tracing of newborn neurons and their developing axons and dendrites in vivo. |

| UNC2025 | UNC2025, CAS:1429881-91-3, MF:C28H40N6O, MW:476.66 | Chemical Reagent |

| Gandotinib | Gandotinib, CAS:1229236-86-5, MF:C23H25ClFN7O, MW:469.9 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

The comparative analysis of enrichment paradigms reveals a consistent theme: complex, multi-modal stimulation is a potent regulator of the core mechanisms of neural plasticity. From enhancing dendritic complexity and synaptic connectivity in healthy brains to promoting axonal regeneration and functional recovery after injury, EE acts through a conserved set of molecular pathways involving neurotrophin signaling and activity-dependent epigenetic remodeling. A critical insight for therapeutic development is the existence of a cell-intrinsic epigenetic barrier that governs the pace of neuronal maturation, particularly in humans [10]. Future research should focus on standardizing enrichment protocols to improve translational outcomes and developing targeted "enviromimetic" drugs that can recapitulate the beneficial effects of a stimulating environment for patients with neurological and psychiatric disorders.

Within the context of neural plasticity research, brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) and insulin-like growth factor-1 (IGF-1) have emerged as critical molecular mediators that translate environmental enrichment into structural and functional neuronal changes. These neurotrophic factors operate through complex, overlapping signaling pathways to govern neurogenesis, synaptic maturation, and neuronal survival throughout the lifespan [15] [16]. The comparative analysis of their mechanisms reveals both synergistic interactions and distinct functional specializations, providing a molecular framework for understanding how enriched environments enhance cognitive function and confer resilience against neurological disorders. BDNF is widely recognized for its pivotal role in activity-dependent plasticity, serving as a key mediator through which experiences shape neuronal networks [16]. IGF-1, while equally crucial for neuronal development, exhibits complementary mechanisms that enhance BDNF responsiveness and signaling efficacy [17]. Together, these factors form an integrated signaling network that calibrates brain connectivity in response to environmental stimuli, with significant implications for both fundamental neuroscience and therapeutic development.

Comparative Molecular Profiles: BDNF versus IGF-1

Table 1: Comparative Properties of BDNF and IGF-1

| Property | BDNF | IGF-1 |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Receptor | Tropomyosin receptor kinase B (TrkB) [15] | IGF-1 Receptor (IGF-1R) [17] |

| Secondary Receptor | p75 neurotrophin receptor (p75NTR) [15] | Insulin receptor (IR) [15] |

| Primary Signaling Pathways | MAPK/ERK, PI3K/Akt, PLCγ [15] | PI3K/Akt, MAPK/ERK [17] [15] |

| Core Cellular Functions | Synaptic plasticity, neuronal survival, differentiation, cognitive function [15] | Neurogenesis, neuronal survival, metabolic regulation [17] [15] |

| Isoforms | proBDNF (precursor), mBDNF (mature) [18] | IGF-1 (multiple splice variants) |

| pro-/mature Form Actions | proBDNF: apoptosis, synaptic pruning (via p75NTR) [18]; mBDNF: synaptic plasticity, neuronal survival (via TrkB) [18] | Not applicable |

| Response to Physical Exercise | Significant increase in circulating levels [19] [20] | Moderate increase in circulating levels [20] |

| Associated Disorders | Alzheimer's disease, Parkinson's disease, depression, autism spectrum disorder [15] [18] | Cognitive impairment, autism spectrum disorder, diabetes mellitus [15] [18] |

Signaling Pathways: Integrated Molecular Mechanisms

The signaling cascades activated by BDNF and IGF-1 represent a highly integrated network that converges on critical pathways regulating neuronal survival, plasticity, and metabolism. Upon binding to their high-affinity tyrosine kinase receptors (TrkB for BDNF and IGF-1R for IGF-1), both factors initiate intracellular signaling that profoundly influences neuronal function and resilience [15].

BDNF Signaling Cascade

BDNF activation of TrkB receptors triggers three principal pathways: the Ras/MAPK/ERK pathway (crucial for neuronal differentiation and survival), the PI3K/Akt pathway (central to metabolic regulation and cell survival), and the PLCγ pathway (which modulates synaptic plasticity through IP3-mediated calcium release and DAG activation of protein kinase C) [15]. The MAPK/ERK pathway is particularly important for BDNF-mediated synaptic plasticity and long-term potentiation (LTP), a cellular correlate of learning and memory [17]. The PI3K/Akt pathway activated by BDNF suppresses apoptosis and promotes cell survival [15]. Notably, BDNF signaling exhibits remarkable context dependency, with mature BDNF (mBDNF) promoting neuronal survival and plasticity through TrkB activation, while its precursor (proBDNF) often induces opposing effects through p75NTR binding, including apoptosis and synaptic pruning [18].

IGF-1 Signaling Network

IGF-1 signaling predominantly activates the PI3K/Akt pathway and, to a lesser extent, the MAPK/ERK pathway in neuronal contexts [17] [15]. The PI3K/Akt pathway is particularly important for IGF-1's neuroprotective effects and its regulation of cellular metabolism. Unlike BDNF, IGF-1 typically induces only transient or minimal activation of the MAPK/ERK pathway in neurons, which may explain its more limited direct effects on neuronal plasticity compared to BDNF [17]. However, IGF-1 significantly enhances BDNF responsiveness by potentiating its biological activity, creating a synergistic relationship that amplifies neurotrophic signaling [17].

Signaling Pathway Integration and Cross-Talk

The signaling pathways of BDNF and IGF-1 exhibit significant convergence, particularly at the level of the PI3K/Akt and MAPK/ERK cascades [15]. This cross-talk creates a coordinated signaling network that regulates critical neuronal functions. Both factors activate transcription factors such as CREB (cAMP response element-binding protein) and CBP (CREB-binding protein), which regulate expression of genes encoding proteins involved in neuronal survival, synaptic plasticity, and stress resistance [15]. Recent evidence indicates that combined BDNF and IGF-1 signaling results in enhanced and sustained activation of these pathways compared to either factor alone, particularly in the context of neuronal protection against excitotoxicity [17].

Figure 1: Integrated signaling pathways of BDNF and IGF-1. BDNF binding to TrkB receptors and IGF-1 binding to IGF-1R activates overlapping intracellular pathways (Ras/MAPK/ERK, PI3K/Akt, PLCγ) that converge on transcription factors like CREB to promote neuronal survival, plasticity, and neurogenesis. proBDNF binding to p75NTR triggers opposing effects including apoptosis and synaptic pruning. IGF-1 potentiates BDNF signaling (dashed line), creating a synergistic relationship [17] [15] [18].

Experimental Approaches: Methodologies for Neurotrophic Factor Research

Assessment of Synergistic Interactions

Research investigating the interplay between BDNF and IGF-1 employs sophisticated experimental paradigms to elucidate their combined effects on neuronal function. A foundational study examining their synergistic relationship utilized cerebrocortical neuron cultures from embryonic mice to demonstrate that co-application of IGF-1 and BDNF enhances intracellular calcium oscillations compared to either factor alone [17]. This experimental protocol involved pre-treatment with IGF-1 (50 ng/mL) for 48 hours followed by BDNF (50 ng/mL) application, with calcium imaging performed using Fura-2 AM fluorescence measurement. Results demonstrated that IGF-1 pre-treatment enhanced BDNF-mediated calcium responses by approximately 40% compared to BDNF alone, indicating potentiation of BDNF signaling efficacy [17]. Additional methodologies in this study included Western blot analysis of receptor expression, revealing that IGF-1 pre-treatment increased TrkB receptor expression, providing a potential mechanism for the enhanced BDNF responsiveness [17].

Exercise Intervention Protocols

Physical exercise represents a powerful non-pharmacological intervention for modulating neurotrophic factor levels, with different exercise parameters producing distinct effects on BDNF and IGF-1 signaling. A systematic review of randomized controlled trials in children aged 5-12 years identified that successful interventions for increasing BDNF levels featured neuromotor activities or martial arts programs conducted with frequencies ≥3 sessions/week for durations ≥12 weeks [19]. In adolescent populations, an 8-week aerobic exercise intervention utilizing treadmill training (3 days/week, 200 kcal/session) demonstrated significant increases in both serum BDNF and IGF-1 compared to sedentary controls [21]. These exercise studies typically employ enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays (ELISA) to quantify neurotrophic factor levels in serum or plasma, with blood collection standardized to morning hours following overnight fasting to control for diurnal variation [21]. Methodological rigor includes measurement of maximal oxygen consumption (VO₂max) to precisely calibrate exercise intensity and ensure consistent metabolic demand across participants [21].

Molecular Signaling Experiments

Elucidation of downstream signaling mechanisms involves techniques such as phosphoprotein analysis to track activation states of pathway components. Experimental approaches include treatment of neuronal cultures with BDNF and/or IGF-1 followed by Western blot analysis with phospho-specific antibodies against key signaling molecules (e.g., phospho-ERK, phospho-Akt) [17]. These investigations have revealed that while both BDNF and IGF-1 activate the PI3K/Akt pathway, BDNF produces more robust and sustained activation of the MAPK/ERK pathway, which is critical for its pronounced effects on synaptic plasticity [17]. Furthermore, combinatorial treatment studies demonstrate that IGF-1 enhances BDNF-mediated ERK phosphorylation, providing mechanistic insight into their synergistic relationship at the molecular level [17].

Figure 2: Experimental workflows for neurotrophic factor research. Clinical studies (top) typically involve exercise interventions with standardized blood collection and ELISA analysis. Preclinical cellular studies (bottom) employ neuronal cultures with controlled growth factor treatments, calcium imaging, and Western blot analysis to elucidate molecular mechanisms [17] [19] [21].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Methodologies

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Assays for Neurotrophic Factor Research

| Reagent/Assay | Specific Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Commercial ELISA Kits | Quantification of BDNF, proBDNF, IGF-1 protein levels in serum/plasma [22] | R&D Systems kits show high specificity for total BDNF (#DBNT00) and proBDNF (#DY3175); specificity for mBDNF kits requires validation [22] |

| Neuronal Cell Cultures | In vitro model for mechanistic studies of neurotrophic signaling [17] | Cerebrocortical neurons from embryonic mice; maintenance in Neurobasal-A medium with B27 supplement [17] |

| Calcium Imaging Reagents | Measurement of intracellular Ca²⺠dynamics as indicator of neuronal activity [17] | Fura-2 AM fluorescent dye; reveals enhanced Ca²⺠oscillations with IGF-1 + BDNF co-treatment [17] |

| Phospho-Specific Antibodies | Detection of activated signaling pathway components [17] | Western blot analysis of phospho-ERK, phospho-Akt to map signaling pathway activation [17] |

| Recombinant Neurotrophins | Application of purified BDNF, IGF-1 for experimental treatments [17] | Typical concentrations: 50 ng/mL; IGF-1 pre-treatment (48h) enhances subsequent BDNF responses [17] |

| Exercise Intervention Protocols | Non-pharmacological modulation of endogenous neurotrophic factors [19] [21] | Treadmill training (3 days/week, 8 weeks) effectively increases serum BDNF and IGF-1 in adolescents [21] |

| Oclacitinib | Oclacitinib|JAK Inhibitor|Research Use Only | Oclacitinib is a potent JAK inhibitor for veterinary immunology research. This product is for Research Use Only and is not intended for diagnostic or therapeutic applications. |

| CCT241161 | CCT241161, MF:C28H27N7O3S, MW:541.6 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Clinical and Translational Implications

The interplay between BDNF and IGF-1 has significant implications for understanding neurodevelopmental disorders and neurodegenerative diseases. In autism spectrum disorder (ASD), altered levels of both factors have been observed, with studies reporting increased IGF-1 and decreased proBDNF in serum of children with ASD compared to controls [18]. These alterations in the balance between neurotrophic and pro-apoptotic signaling may contribute to the aberrant neural connectivity observed in ASD [18]. In epilepsy, reduced serum levels of both BDNF and IGF-1 correlate with disease duration, seizure frequency, and autonomic dysfunction, suggesting their potential utility as biomarkers of disease progression [23]. Notably, the synergistic relationship between these factors extends to therapeutic applications, as evidenced by research showing that IGF-1 administration reduces seizure severity and protects against cognitive deficits in experimental models of temporal lobe epilepsy [23].

The relevance of BDNF and IGF-1 signaling extends to pharmacological treatments for neuropsychiatric disorders. Antidepressant medications have been shown to activate TrkB signaling and gradually increase BDNF expression, with behavioral effects that are dependent on BDNF signaling through TrkB receptors, at least in rodent models [16]. This suggests that a key mechanism of antidepressant action involves the facilitation of neurotrophic signaling and the reactivation of developmental-like plasticity in adult circuits, a process termed iPlasticity [16]. The interplay between IGF-1 and BDNF may therefore represent a promising target for novel therapeutic approaches that aim to enhance neural plasticity in a range of neurological and psychiatric conditions.

The comparative analysis of BDNF and IGF-1 reveals a sophisticated signaling network in which these molecular mediators play complementary yet distinct roles in regulating neural plasticity. While BDNF serves as a primary regulator of activity-dependent synaptic plasticity, IGF-1 enhances BDNF responsiveness and promotes neuronal survival through overlapping but distinct signaling pathways. Their synergistic relationship creates a coordinated system that translates environmental experiences, including physical exercise and cognitive enrichment, into structural and functional adaptations within neural circuits. Future research directions should include the development of more specific reagents for discriminating between neurotrophic factor isoforms, particularly mature BDNF versus its precursor forms, as their opposing biological functions necessitate precise quantification [22]. Additionally, longitudinal studies examining the temporal dynamics of BDNF and IGF-1 signaling across different developmental stages will enhance our understanding of their roles in both health and disease. The integrated investigation of these key molecular mediators continues to provide critical insights into the fundamental mechanisms of neural plasticity while offering promising avenues for therapeutic intervention in neurological and psychiatric disorders.

Neuroplasticity, the nervous system's capacity to adapt its structure and function in response to experience, operates through two fundamentally distinct yet complementary mechanisms: experience-expectant and experience-dependent plasticity. Experience-expectant plasticity involves pre-programmed brain development during critical periods in early life, where the brain anticipates specific environmental inputs to refine neural circuits. In contrast, experience-dependent plasticity facilitates learning throughout life by incorporating unique individual experiences into neural architecture without strict temporal constraints. This comparative analysis examines the mechanisms, temporal windows, and functional roles of these plasticity forms, drawing on experimental data from molecular, systems, and behavioral neuroscience. Understanding their interplay provides crucial insights for developing targeted interventions in neurodevelopmental disorders, cognitive enhancement, and neural repair.

Defining the Core Concepts

Experience-Expectant Plasticity

Experience-expectant plasticity refers to the developing brain's reliance on universal experiences that occur predictably in normal environments to fine-tune neural circuits during limited developmental windows [24]. This process underpins the maturation of fundamental sensory and cognitive systems, where the brain produces an initial surplus of synapses and selectively stabilizes those reinforced by expected environmental input while pruning others [25]. The visual system provides a canonical example: for ocular dominance columns to form properly, the brain expects balanced visual input from both eyes during a specific critical period in early development [26]. When deprivation occurs during this period (such as from cataracts or strabismus), visual processing can be permanently impaired, demonstrating the time-limited nature of this plasticity mechanism [24] [26].

Experience-Dependent Plasticity

Experience-dependent plasticity involves changes in existing neural circuits that occur in response to specific learning experiences that vary across individuals [27]. Unlike experience-expectant plasticity, this mechanism is not constrained to specific developmental periods and facilitates learning throughout the lifespan, though plasticity remains most pronounced in childhood [27]. This form of plasticity enables the brain to incorporate unique information from personal experiences through the selective strengthening of particular synaptic connections in response to experience alongside the elimination of others that are under-utilized [27]. Examples include the neuroplastic changes associated with learning a musical instrument, acquiring a new language, or developing specialized skills through training [27]. The specific neural circuits that undergo change are determined by the type of experience, with the intensity and duration of environmental experiences influencing the degree of neuroplasticity that occurs [27].

Comparative Mechanisms: From Synapses to Systems

Table 1: Fundamental Characteristics at a Glance

| Characteristic | Experience-Expectant Plasticity | Experience-Dependent Plasticity |

|---|---|---|

| Purpose | Fine-tuning pre-established neural circuits using expected experiences [24] | Incorporating unique individual experiences into neural architecture [27] |

| Developmental Timing | Limited critical periods, primarily in early childhood [24] [28] | Lifelong, though most pronounced in childhood [27] |

| Environmental Reliance | Depends on universal experiences common to all species members [24] | Depends on idiosyncratic experiences that vary between individuals [27] |

| Neural Mechanisms | Selective synaptic stabilization & pruning; inhibition-gated critical periods [28] [26] | Synaptic strengthening/weakening; dendritic spine growth; neurogenesis in specific circuits [27] |

| Sensitivity to Deprivation | Highly sensitive; can lead to permanent functional deficits [24] | Less sensitive to specific deprivation; varies with experience quality [27] |

| Role of Attention | Passive exposure sufficient to drive plasticity [26] | Often requires active attention and engagement [26] |

Molecular and Cellular Mechanisms

The molecular machinery underlying these plasticity forms exhibits significant specialization. Experience-expectant plasticity critically depends on the maturation of inhibitory circuits, particularly those involving parvalbumin-positive (PV+) interneurons and GABAergic signaling [26]. The developmental increase in GABAergic inhibition appears to gate the opening and closure of critical periods, with genetic manipulations that suppress PV+ interneuron activity extending plasticity windows into adulthood [26]. During critical periods, NMDA receptor-mediated signaling plays a crucial role in initiating plasticity, while specific molecular brakes such as myelin-related factors increasingly restrict plasticity as the critical period closes [28].

Experience-dependent plasticity employs more diverse molecular mechanisms that vary by brain region and experience type. This includes AMPA receptor trafficking to strengthen individual synapses, with some forms involving calcium-permeable AMPARs at layer 4-2/3 synapses but not necessarily at layer 2/3-2/3 synapses, demonstrating remarkable input specificity [29]. Brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) signaling features prominently in both forms but serves different roles—orchestrating expected maturation in experience-expectant plasticity versus mediating activity-dependent changes in experience-dependent plasticity [30]. Structural changes in experience-dependent plasticity include the formation of new dendritic spines and synaptic connections, with persistent changes in spine morphology observed following skill learning or exposure to enriched environments [31].

Circuit-Level Organization

At the circuit level, these plasticity forms operate through distinct organizational principles. Experience-expectant plasticity typically follows a systems-level progression, with critical periods opening and closing in a hierarchical sequence across brain regions [26]. Sensory areas mature before association cortices, reflecting the sequential development from basic perceptual capabilities to higher cognitive functions. This sequential organization ensures that foundational circuits are properly established before becoming building blocks for more complex networks.

Experience-dependent plasticity exhibits more localized and distributed organization, with changes occurring specifically in circuits engaged by particular experiences [27]. For example, complex motor skill training induces structural expansion primarily in motor and cerebellar regions, whereas language learning predominantly engages perisylvian networks. The enriched environment paradigm demonstrates this distributed specificity, where increased physical activity, sensory stimulation, cognitive challenge, and social interaction collectively induce plastic changes across multiple brain systems in an experience-specific manner [31].

Figure 1: Distinct mechanistic pathways for experience-expectant (yellow) and experience-dependent (green) plasticity.

Experimental Approaches and Protocols

Paradigms for Studying Experience-Expectant Plasticity

Research investigating experience-expectant plasticity typically employs sensory deprivation or selective exposure protocols during developmentally precise windows:

Monocular Deprivation (Ocular Dominance Plasticity): This classic paradigm involves suturing one eyelid closed for defined periods during postnatal development [26]. The standard protocol involves lid suture in postnatal day 21-28 mice (or equivalent developmental stage in other species) for 2-7 days, followed by electrophysiological assessment of visual cortex responses to each eye [26]. Measurements include quantification of ocular dominance scores, where neurons are categorized based on their relative responsiveness to stimulation of each eye (categories 1-7, with 1 representing exclusive contralateral eye dominance and 7 representing exclusive ipsilateral eye dominance) [26].

Auditory Frequency Exposure: Developing animals are reared in environments dominated by specific acoustic frequencies (e.g., 7 kHz pulsed tones) during critical periods for auditory map formation [26]. The typical protocol exposes postnatal day 11-13 rat pups to tone pulses (200 ms duration, 1 Hz) for 24 hours, followed by mapping of frequency representation in primary auditory cortex using microelectrode recordings [26]. This results in significant expansion of cortical territory representing the exposed frequency.

Paradigms for Studying Experience-Dependent Plasticity

Experience-dependent plasticity research employs paradigms emphasizing skill acquisition, environmental complexity, and specific learning experiences:

Enriched Environment Housing: This paradigm compares animals housed in standard laboratory cages versus complex environments containing various toys, tunnels, running wheels, and social companions [31]. Standard protocols house rodents for 4-8 weeks in large cages (typically 60×60×60 cm or larger) containing 10-15 different objects that are rearranged daily and completely replaced with novel objects weekly [31]. Control groups are housed in standard laboratory cages (typically 30×20×15 cm) with only bedding, food, and water. Outcome measures include dendritic branching quantification (e.g., Golgi staining), synaptic density measurements, neurogenesis assays, and behavioral performance on learning and memory tasks.

Single Whisker Experience (SWE): This somatosensory paradigm involves removing all but a single large whisker (e.g., the D1 whisker) for 24 hours in young mice to study input-specific cortical plasticity [29]. The standard protocol uses postnatal day 11-17 mice with all but one whisker plucked, after which animals return to their home cage for 24 hours before electrophysiological recording [29]. Whole-cell recordings from layer 2/3 pyramidal neurons in the spared whisker barrel column measure synaptic strength changes, including AMPA/NMDA receptor ratios and rectification indices.

Table 2: Experimental Models and Quantitative Outcomes

| Experimental Paradigm | Species | Key Intervention | Primary Outcomes | Plasticity Type |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Monocular Deprivation [26] | Mouse, Cat | Unilateral eyelid suture during P21-P28 | Ocular dominance shift: ~70% reduction in response to deprived eye | Experience-Expectant |

| Single Whisker Experience [29] | Mouse | All-but-one whisker removal for 24h | Synaptic strengthening: ~40% increase in AMPA receptor-mediated currents | Experience-Dependent |

| Enriched Environment [31] | Rat, Mouse | Complex housing for 4-8 weeks | Dendritic branching: ~20% increase; Synaptic density: ~15% increase | Experience-Dependent |

| Auditory Critical Period [26] | Rat | Specific tone exposure during P11-P13 | Cortical representation: 2-3 fold expansion for exposed frequency | Experience-Expectant |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Research Reagents for Investigating Neural Plasticity

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Research Application | Function in Plasticity Studies |

|---|---|---|---|

| GABAergic Modulators | Muscimol (GABAA agonist), Bicuculline (GABAA antagonist) [26] | Critical period manipulation | Artificially open or close plasticity windows by modulating inhibition |

| Glutamate Receptor Agents | Ifenprodil (NR2B antagonist), CNQX (AMPAR antagonist), d-APV (NMDAR antagonist) [29] | Synaptic plasticity mechanisms | Isolate receptor-specific contributions to plasticity at different synapses |

| Activity Reporters | fosGFP transgenic mice, c-Fos immunohistochemistry [29] | Neural activity mapping | Identify circuits activated by specific experiences or during critical periods |

| Structural Plasticity Tools | DiOlistics, Golgi staining, Thy1-GFP transgenic mice [31] | Dendritic spine imaging | Quantify structural changes following experience or during development |

| In Vivo Recording Methods | Chronic electrode arrays, two-photon calcium imaging [32] | Longitudinal monitoring | Track neural changes throughout learning or developmental periods |

| Molecular Plasticity Markers | BDNF antibodies, pCREB antibodies, delta Fos B assays [30] | Signaling pathway analysis | Detect molecular correlates of plastic changes in specific circuits |

| Entospletinib | Entospletinib|Selective SYK Inhibitor|For Research | Bench Chemicals | |

| Foretinib | Foretinib, CAS:849217-64-7, MF:C34H34F2N4O6, MW:632.7 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

Signaling Pathways in Plasticity

The distinct molecular pathways governing each plasticity form represent promising targets for therapeutic intervention:

Experience-Expectant Signaling Cascades: The opening of critical periods requires GABAergic circuit maturation triggered by sensory experience [26]. Visual experience after eye opening drives increased activity in cortical circuits, leading to BDNF release that promotes the development of inhibitory synapses, particularly onto parvalbumin-positive interneurons [26]. Mature GABAergic signaling then triggers extracellular matrix remodeling and perineuronal net formation, which progressively restricts plasticity as the critical period closes [28]. Molecular brakes including myelin-related proteins (Nogo-A, MAG, OMgp) and their common receptor (NgR) contribute to this closure by limiting structural plasticity [26].

Experience-Dependent Signaling Pathways: Experience-dependent plasticity engages more diverse signaling mechanisms, including NMDA receptor activation followed by calcium influx that triggers downstream kinases (CaMKII, PKC, PKA) and transcription factors (CREB) [27] [30]. This leads to AMPA receptor trafficking and insertion at potentiated synapses, with some forms involving delivery of calcium-permeable AMPARs at layer 4-2/3 synapses but not layer 2/3-2/3 synapses [29]. Growth factors including BDNF and neurotransmitters such as acetylcholine and norepinephrine modulate these processes, particularly when plasticity requires attention [26]. Structural adaptations involve cytoskeletal reorganization mediated by Rho GTPases and subsequent dendritic spine growth or modification [31].

Figure 2: Signaling pathways governing experience-expectant (yellow) and experience-dependent (green) plasticity. Note the sequential nature of critical period regulation versus the more parallel signaling in experience-dependent mechanisms.

Implications for Research and Therapeutics

The distinction between these plasticity mechanisms carries significant implications for research and drug development:

Neurodevelopmental Disorders: Understanding experience-expectant plasticity provides crucial insights into disorders such as autism spectrum disorder and schizophrenia, which may involve improper timing of critical periods or disrupted inhibitory circuit maturation [28]. Therapeutic strategies aiming to reopen plasticity windows in these conditions are exploring GABAergic modulation and chondroitin sulfate proteoglycan degradation to remove perineuronal nets [28].

Learning and Memory Enhancement: Experience-dependent plasticity mechanisms offer targets for cognitive enhancement and skill acquisition. Research indicates that compounds promoting glutamatergic signaling, neurotrophic factor support, or mitochondrial function may accelerate learning, while non-pharmacological approaches using enriched environments demonstrate synergistic benefits [31].

Neurological Rehabilitation: Following CNS injury, the adult brain exhibits heightened plasticity that shares mechanisms with developmental experience-dependent plasticity [31]. Stroke rehabilitation research shows that enriched environments combining physical activity, sensory stimulation, and social interaction promote functional recovery through mechanisms including enhanced neurogenesis, synaptogenesis, and dendritic branching [31]. Novel approaches exploring the plasticity-promoting effects of certain psychedelics (e.g., psilocybin, ketamine) aim to reopen periods of heightened meta-plasticity for therapeutic benefit [33].

Addiction Medicine: Substance use disorders represent maladaptive experience-dependent plasticity, where drugs of abuse co-opt natural reward learning mechanisms [30]. Chronic drug exposure produces stable changes in glutamate homeostasis and dendritic spine morphology in reward-related circuits, creating enduring addiction memories [30]. Emerging treatments target these mechanisms, with N-acetylcysteine showing promise in restoring glutamate homeostasis and reducing drug-seeking behavior in both animal models and human trials [30].

Experience-expectant and experience-dependent plasticity represent complementary yet distinct neurobiological strategies for adapting brain function to environmental demands. While experience-expectant plasticity creates a foundation of neural circuitry through precisely timed developmental windows, experience-dependent plasticity enables lifelong learning and adaptation to unique experiences. The continuing elucidation of their molecular mechanisms, circuit implementations, and temporal constraints provides not only fundamental insights into brain development and function but also promising avenues for therapeutic intervention across a spectrum of neurological and psychiatric conditions. Future research will likely focus on understanding how these plasticity forms interact throughout the lifespan and developing precisely timed interventions that optimize brain function across development, adulthood, and aging.

The understanding of the brain as a dynamic, changeable organ represents one of the most significant paradigm shifts in modern neuroscience. This transformation originated with the pioneering work of Dr. Marian Diamond in the 1960s, whose anatomical evidence first demonstrated the brain's capacity for change—a property now known as neuroplasticity [34] [35]. Before Diamond's groundbreaking experiments, neuroscientific dogma maintained that the brain was a static, immutable entity that could not change after early development [34] [36]. Diamond's research team at UC Berkeley challenged this entrenched view by providing tangible evidence that the brain's structure could be altered by experience throughout the lifespan [37]. When she first presented her findings demonstrating brain plasticity, she was met with substantial skepticism, even reportedly being confronted by an audience member who shouted, "Young lady, that brain cannot change!" [34] [35]. Undeterred, Diamond continued her investigations, ultimately establishing the foundational principle that enrichment induces measurable anatomical changes in the cerebral cortex [34].

Her work has since launched an entire field of investigation into environmental enrichment (EE), defined as a model incorporating "complex physical, social, cognitive, motor, and somatosensory stimuli" [38]. This review provides a comparative analysis of enrichment environments in neural plasticity research, tracing the historic foundations established by Marian Diamond through contemporary experimental approaches and their translational applications. We examine the quantitative anatomical and behavioral outcomes across model organisms, detail standardized experimental methodologies, and explore the emerging signaling pathways that mediate these effects, providing researchers and drug development professionals with a comprehensive framework for evaluating enrichment paradigms.

Marian Diamond's Foundational Experiments

Methodological Framework and Anatomical Findings

Marian Diamond's experimental protocol established the gold standard for early environmental enrichment research. Her seminal 1964 study employed a controlled comparative design using laboratory rats divided into two housing conditions [37] [36]. The impoverished environment consisted of a solitary rat housed in a small, desolate cage with no stimulation, while the enriched environment contained a group of 10-12 rats in a large cage furnished with various objects (e.g., toys, ladders, and mazes) that were changed and rearranged regularly to maintain novelty and complexity [36]. This experimental period typically lasted 80 days, after which Diamond conducted systematic anatomical analysis of the cerebral cortex [36].

Her quantitative histological measurements revealed that rats exposed to the enriched environment developed a cerebral cortex that was 6% thicker compared to impoverished rats [37] [36]. This increased cortical thickness represented one of the first anatomical demonstrations of neuroplasticity in a mammalian brain. Diamond later extended these findings to aging populations, demonstrating that cortical changes could occur at any age, including in older animals living up to 904 days [35] [36]. Importantly, she also observed that gentle handling and petting the rats daily could further enhance both brain development and lifespan, introducing the critical dimension of tactile stimulation to enrichment paradigms [36].

Table 1: Key Quantitative Findings from Marian Diamond's Enrichment Experiments

| Measurement Parameter | Experimental Group | Control Group | Percentage Change | Significance |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cortical Thickness | Increased | Baseline | +6% | p < 0.05 |

| Glial Cell Numbers | Higher | Lower | Significant increase | p < 0.05 |

| Learning Capacity | Enhanced | Diminished | Notable improvement | Observable |

| Lifespan (with handling) | Extended | Standard | Increased | Measurable |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Materials

The following table details key reagents and materials used in Diamond's foundational experiments and their contemporary equivalents:

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions for Enrichment Studies

| Item/Category | Function in Experimental Protocol | Specific Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Animal Models | Subject for neuroanatomical and behavioral analysis | Laboratory rats (Rattus norvegicus), Drosophila melanogaster [39] |

| Environmental Housing | Controlled manipulation of sensory, motor, and social stimulation | Impoverished: small solitary cages; Enriched: large social cages with novel objects [36] |

| Histological Tools | Tissue preparation and anatomical measurement | Celloidin embedding, microscopic analysis, cortical thickness measurement [37] |

| Molecular Assays | Analysis of cellular and molecular changes | Glial cell counts, dendritic spine analysis, protein expression [37] |

| Behavioral Assessment | Quantitative measurement of cognitive and behavioral outcomes | Learning tasks, problem-solving tests, social behavior observation [38] [40] |

| VX-166 | VX-166, MF:C22H21F4N3O8, MW:531.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Birinapant | Birinapant, CAS:1260251-31-7, MF:C42H56F2N8O6, MW:806.9 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Modern Experimental Protocols in Environmental Enrichment Research

Standardized Methodologies for Preclinical Research

Contemporary environmental enrichment protocols have evolved from Diamond's original paradigm while maintaining the core principle of enhanced sensory, cognitive, and social stimulation. Standardized methodologies now include carefully calibrated enrichment components that can be systematically manipulated to isolate their individual contributions to neural plasticity [34]. The complex physical environment typically consists of large cages (approximately 1m² for rodents) containing various non-toxic objects of different sizes, textures, and shapes, such as running wheels, tunnels, nesting materials, climbing structures, and manipulable toys [34] [40]. These objects are rearranged and replaced with novel items according to a predetermined schedule (typically 2-3 times weekly) to maintain cognitive engagement and prevent habituation [40].

The social enrichment component involves housing animals in stable groups of appropriate conspecifics (typically 3-5 for mice, 10-12 for rats) to facilitate natural species-typical social behaviors, including hierarchical establishment, grooming, and play behavior [34]. For cognitive and motor stimulation, food is often hidden within the bedding or placed in puzzle feeders to encourage natural foraging behaviors and cognitive processing, while elevated platforms and complex terrains promote balance and coordinated movement [40]. The minimum exposure duration to demonstrate significant neural effects is generally 4-6 weeks, though many studies employ longer durations or life-long enrichment [34]. Control groups remain important and include both standard-housed (typically smaller cages with minimal enrichment) and impoverished groups (solitary confinement in bare cages) to establish a continuum of environmental complexity [36].

Quantitative Assessment of Enrichment Efficacy

Modern research has developed sophisticated quantitative metrics to evaluate the efficacy of enrichment protocols across multiple dimensions. Behavioral assessments typically include behavioral diversity indexes (counting the number of different species-typical behaviors observed), cognitive performance measures (such as water maze learning, novel object recognition, and problem-solving tasks), and reductions in abnormal behaviors (including stereotypies, excessive grooming, or anxiety-like behaviors) [40]. Neuroanatomical measurements have expanded beyond cortical thickness to include dendritic branching complexity (through Golgi staining), synaptic density counts (electron microscopy), neurogenesis rates (BrdU labeling in hippocampal dentate gyrus), and glial cell proliferation [34] [37].

Molecular analyses now routinely measure changes in neurotrophic factors (BDNF, GDNF, NGF via ELISA or Western blot), synaptic plasticity proteins (PSD-95, synapsin-I), neurotransmitter systems, and immediate early gene expression (c-fos, Arc) as indicators of neuronal activation [34] [38]. These multidimensional assessment protocols allow researchers to establish robust correlations between specific enrichment components and their neural consequences, providing more targeted insights for therapeutic development.

Comparative Analysis of Enrichment Effects Across Experimental Models

Anatomical and Behavioral Outcomes Across Species

Environmental enrichment research has expanded beyond rodent models to include diverse species, providing comparative insights into neural plasticity mechanisms. The following table synthesizes quantitative findings across experimental models:

Table 3: Comparative Analysis of Enrichment Effects Across Species and Conditions

| Experimental Model | Enrichment Type | Anatomical/Neural Changes | Behavioral/Functional Outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Laboratory Rats (Diamond, 1964) | Complex environment with toys, social groups | 6% thicker cerebral cortex; Increased glial numbers [36] | Enhanced learning capacity; Improved problem-solving [37] |

| Giant Pandas (Swaisgood et al., 2001) | Structural habitat modifications, sensory stimuli | Not measured | Reduced stereotypic behaviors; Increased behavioral diversity [40] |

| Drosophila melanogaster (2019) | Structural complexity, exploratory opportunities | Neural changes inferred | Behavior variability dependent on genotype and enrichment type [39] |

| Human MDD Patients (2022) | Cognitive, social, physical activities | BDNF level changes inferred | Lower depression scores; Improved cognitive function [38] |

| Aging Rats (Rapley et al.) | Environmental complexity | Transient increase in CNP in young rats only [34] | Age-related declines in environmental sensitivity [34] |

Sex-Specific and Age-Dependent Responses

Contemporary research has revealed that enrichment effects are not uniform across all populations. Sexual dimorphism represents a significant factor in enrichment efficacy, with studies demonstrating sexually dimorphic effects of EE on behavior, neurotrophic factor expression (BDNF), and receptor subunit composition [34]. For instance, Grech et al. found that combining BDNF haploinsufficiency with chronic corticosterone administration created a "two-hit model" with distinct sex-specific responses to enrichment, correlating with differential expression of TrkB receptors and specific NMDA receptor subunits [34].

Age-dependent effects also significantly influence enrichment outcomes. Research by Rapley et al. demonstrated that enrichment housing transiently increased C-type Natriuretic Peptide (CNP) availability in young but not older rats, suggesting age-related declines in environmental sensitivity [34]. Similarly, Mason et al. showed that nesting enrichment (closed nest boxes) produced beneficial effects in a neonatal hypoxia-ischemia model, with molecular correlates including BDNF and GDNF expression, but these effects displayed significant sexual dimorphism [34]. These findings highlight the critical importance of considering demographic variables in both preclinical research and clinical translation of enrichment paradigms.

Molecular Mechanisms: Signaling Pathways in Neuroplasticity

Key Signaling Pathways Activated by Enrichment

Environmental enrichment engages multiple interconnected signaling pathways that collectively mediate its effects on neural plasticity. The neurotrophic signaling pathway represents a central mechanism, with enrichment robustly increasing brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) expression in the hippocampus and cerebral cortex [38]. BDNF activation of its high-affinity receptor TrkB (tropomyosin receptor kinase B) triggers intracellular cascades including MAPK/ERK, PI3K/Akt, and PLCγ pathways that promote neuronal survival, dendritic arborization, and synaptic strengthening [34]. Additionally, enrichment modulates glutamatergic signaling, specifically altering the expression and phosphorylation of NMDA receptor subunits, which are critical for long-term potentiation (LTP) and learning processes [34].

The serotonergic system also undergoes significant modulation following enrichment, with transcriptional changes in components of serotonin signaling observed after just two weeks of environmental enrichment [34]. These neurochemical changes are accompanied by endocrine modulation, particularly of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis, with enrichment buffering corticosterone responses to stress and mitigating HPA axis dysregulation following enrichment removal [34]. Recently, non-neuronal components have been recognized as important mediators, with enrichment increasing glial cell proliferation and enhancing expression of glial-derived neurotrophic factor (GDNF), highlighting the involvement of previously underappreciated cell types in experience-dependent plasticity [34] [37].

Translational Applications and Clinical Implications

From Laboratory Findings to Clinical Interventions

The translational potential of environmental enrichment research extends across numerous neurological and psychiatric conditions. In neurodevelopmental disorders, EE paradigms have shown promise in models of autism, with clinical adaptations applied as treatment components that emphasize structured sensory integration and social interaction [38]. For neurodegenerative diseases, enrichment principles have been investigated in Huntington's disease models, where even relatively short-term enrichment (2 weeks) produced transcriptional modulation of serotonergic system components [34]. Similarly, in stroke rehabilitation, environmental enrichment concepts have informed therapeutic approaches, though significant challenges remain in aligning animal models with clinical applications [34].

The combination of enrichment with other therapeutic modalities represents an emerging frontier with substantial clinical potential. Bhaskar et al. demonstrated that combining EE with deep-brain stimulation (DBS) produced enhanced anxiolytic effects compared to DBS alone in standard-housed animals [34]. Similarly, research exploring enrichment alongside pharmacological interventions (so-called "enviromimetics") has revealed additive and potentially synergistic effects that could significantly enhance therapeutic efficacy across a spectrum of neurological and psychiatric disorders [34]. These combination approaches acknowledge the multifactorial nature of brain disorders while leveraging the multi-target mechanisms of action provided by enrichment paradigms.

Quantitative Assessment in Human Populations