Comparative Efficacy of Cognitive Rehabilitation Techniques in Post-Stroke Cognitive Impairment: A Systematic Analysis for Research and Development

This article provides a comprehensive comparative analysis of contemporary cognitive rehabilitation techniques for post-stroke cognitive impairment (PSCI), tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals.

Comparative Efficacy of Cognitive Rehabilitation Techniques in Post-Stroke Cognitive Impairment: A Systematic Analysis for Research and Development

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive comparative analysis of contemporary cognitive rehabilitation techniques for post-stroke cognitive impairment (PSCI), tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals. It synthesizes recent evidence from randomized controlled trials and meta-analyses to evaluate the efficacy of diverse interventions, including non-invasive brain stimulation (tDCS, rTMS), technology-assisted rehabilitation (Virtual Reality, computer-based training), pharmacological approaches, and conventional cognitive training. The analysis explores neurobiological mechanisms, methodological considerations for clinical application, optimization strategies to address heterogeneity in treatment response, and comparative effect sizes across modalities. By integrating foundational science with applied clinical research, this review aims to inform the development of targeted, multimodal therapeutic strategies and guide future research directions in stroke cognitive rehabilitation.

The Neurobiological Landscape of Post-Stroke Cognitive Impairment and Foundational Rehabilitation Principles

Post-stroke cognitive impairment (PSCI) represents a significant challenge in stroke recovery, profoundly affecting patients' functional independence and quality of life. As stroke remains a leading cause of adult disability globally, understanding the epidemiology, specific cognitive domain deficits, and subsequent impact on functional outcomes is crucial for developing targeted rehabilitation strategies. This review synthesizes current evidence on PSCI prevalence, identifies the most commonly affected cognitive domains, and elucidates the relationship between cognitive deficits and functional recovery trajectories. The objective assessment of this burden provides a foundation for optimizing cognitive rehabilitation within stroke research and clinical practice, ultimately aiming to improve long-term outcomes for stroke survivors through evidence-based interventions.

Epidemiological Profile of Post-Stroke Cognitive Impairment

Prevalence and Scope of the Problem

Post-stroke cognitive impairment is remarkably prevalent among stroke survivors. A recent cross-sectional study conducted at the National Hospital of Sri Lanka involving 117 stroke survivors aged 40 years and above found a PSCI prevalence of 70.1% when assessed using the Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA) in the 3-12 months post-stroke period [1]. This study further categorized the severity of cognitive impairment, with 39% of patients demonstrating mild, 30% moderate, and 1.1% severe cognitive impairment [1]. These figures highlight that PSCI is not an uncommon complication but rather affects the majority of stroke survivors, necessitating systematic assessment and intervention.

The high prevalence of PSCI establishes it as a central concern in stroke rehabilitation. With stroke being the fourth leading cause of disability-adjusted life years globally [2], the additional burden of cognitive impairment significantly compounds the disability experienced by survivors. The epidemiological data underscores the need for routine cognitive screening in post-stroke care protocols and allocation of healthcare resources toward cognitive rehabilitation services.

Stroke Subtypes and Cognitive Outcomes

The trajectory of cognitive recovery varies across different stroke subtypes, which has implications for prognosis and rehabilitation planning. A comprehensive retrospective analysis of 646 patients with different stroke subtypes revealed that patients with subarachnoid hemorrhage (SAH) generally experience poorer long-term outcomes compared to those with ischemic stroke (IS) or intracerebral hemorrhage (ICH) [2].

The most substantial difference was observed in productivity frequency scores (a subdomain of participation measurement), with the SAH group exhibiting significantly lower scores (0.04 [0-0.09]) compared to IS (0.39 [0.33-0.45]) and ICH (0.44 [0.37-0.51]) groups (P < 0.001) [2]. This suggests that the stroke subtype not only influences acute recovery but also long-term functional participation, particularly in productive activities such as work and household responsibilities. Understanding these subtype-specific profiles enables clinicians to set realistic expectations and tailor rehabilitation approaches to address the unique challenges associated with different stroke mechanisms.

Table 1: Prevalence and Severity Distribution of Post-Stroke Cognitive Impairment

| Characteristic | Overall PSCI Prevalence | Mild Impairment | Moderate Impairment | Severe Impairment |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Percentage | 70.1% | 39% | 30% | 1.1% |

| Assessment Tool | Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA) | MoCA | MoCA | MoCA |

Table 2: Long-Term Participation Outcomes by Stroke Subtype

| Stroke Subtype | Productivity Frequency Score | Social Participation | Community Participation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ischemic Stroke | 0.39 [0.33-0.45] | Similar recovery pattern | Similar recovery pattern |

| Intracerebral Hemorrhage | 0.44 [0.37-0.51] | Similar recovery pattern | Similar recovery pattern |

| Subarachnoid Hemorrhage | 0.04 [0-0.09] | Poorer outcomes | Poorer outcomes |

Domain-Specific Cognitive Deficits in PSCI

Profile of Affected Cognitive Domains

Post-stroke cognitive impairment manifests across multiple cognitive domains, with particular patterns emerging in recent research. Domain-specific analysis reveals that attention and executive functions are significantly associated with functional outcomes [1]. The attention component has been identified as a key indicator for basic activities of daily living (ADL) independence (β = 0.303, p = 0.005), while executive functions are strongly associated with balance abilities (β = 0.439, p = 0.001) [1].

The differential impact of specific cognitive domains on various functional outcomes highlights the need for targeted assessment and intervention. Executive dysfunction, which encompasses problems with planning, organization, cognitive flexibility, and self-monitoring, appears particularly disruptive to complex motor tasks like balance maintenance. Similarly, attentional deficits impair the capacity to perform basic self-care activities, suggesting that different cognitive domains contribute uniquely to the spectrum of post-stroke disability.

Assessment Methodologies for Cognitive Domains

Comprehensive cognitive assessment following stroke requires a multifaceted approach. The Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA) is widely used to evaluate global cognitive function, with specific subdomains assessing visuospatial and executive skills, naming, attention, language, abstraction, delayed memory, and orientation [2]. The MoCA provides a broad screening of cognitive status, but often requires supplementation with domain-specific measures for detailed rehabilitation planning.

For research purposes, more extensive test batteries are employed to capture the complexity of cognitive deficits. Studies investigating cognitive rehabilitation efficacy commonly utilize standardized instruments such as the Western Aphasia Battery (WAB), which assesses spontaneous speech, auditory comprehension, repetition, and naming abilities [3]. These detailed assessments enable researchers to identify specific cognitive deficits and measure changes in response to targeted interventions, providing valuable data for evidence-based practice in cognitive rehabilitation.

Impact of Cognitive Impairment on Functional Outcomes

Activities of Daily Living and Functional Independence

Cognitive function following stroke is significantly associated with balance, mobility, and functional independence in activities of daily living (ADLs) [1]. Research demonstrates that improved global cognitive function correlates significantly with all functional outcomes, with basic ADL independence showing the highest effect size (η²p = 0.257), followed by instrumental ADL independence (η²p = 0.193), improved mobility (η²p = 0.077), and balance performance (η²p = 0.056) [1].

These findings underscore the profound impact of cognitive impairment on the fundamental activities necessary for independent living. Basic ADLs include self-care tasks such as feeding, dressing, and personal hygiene, while instrumental ADLs encompass more complex activities like managing finances, medication administration, and household management. The strong association between cognitive function and ADL performance suggests that cognitive deficits may be a primary driver of dependency following stroke, highlighting the importance of integrating cognitive rehabilitation with physical rehabilitation to optimize functional recovery.

Participation and Quality of Life

Beyond basic functional tasks, cognitive impairment significantly affects participation in social, community, and vocational activities, ultimately impacting overall quality of life. The Participation Measure-3 Domains, 4 Dimensions (PM-3D4D) captures these aspects, evaluating social participation, community participation, and productivity across both frequency and perceived difficulty dimensions [2]. Research indicates that better activity function at discharge is an independent predictor of higher PM-3D4D scores 12 months post-dischcharge [2].

The restricted participation observed in PSCI patients has profound implications for quality of life and mental health. Difficulties with resuming work, engaging in leisure activities, and maintaining social relationships contribute to post-stroke depression and reduced life satisfaction. This highlights the importance of measuring participation outcomes alongside traditional impairment-based measures to fully capture the impact of cognitive deficits on patients' lives and inform comprehensive rehabilitation approaches.

Table 3: Association Between Cognitive Functions and Functional Outcomes

| Functional Outcome | Effect Size (η²p) | Most Relevant Cognitive Domain | Domain Association (β) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Basic ADL Independence | 0.257 | Attention | β = 0.303, p = 0.005 |

| Instrumental ADL Independence | 0.193 | Executive Functions | Not specified |

| Mobility | 0.077 | Global Cognition | Not specified |

| Balance Performance | 0.056 | Executive Functions | β = 0.439, p = 0.001 |

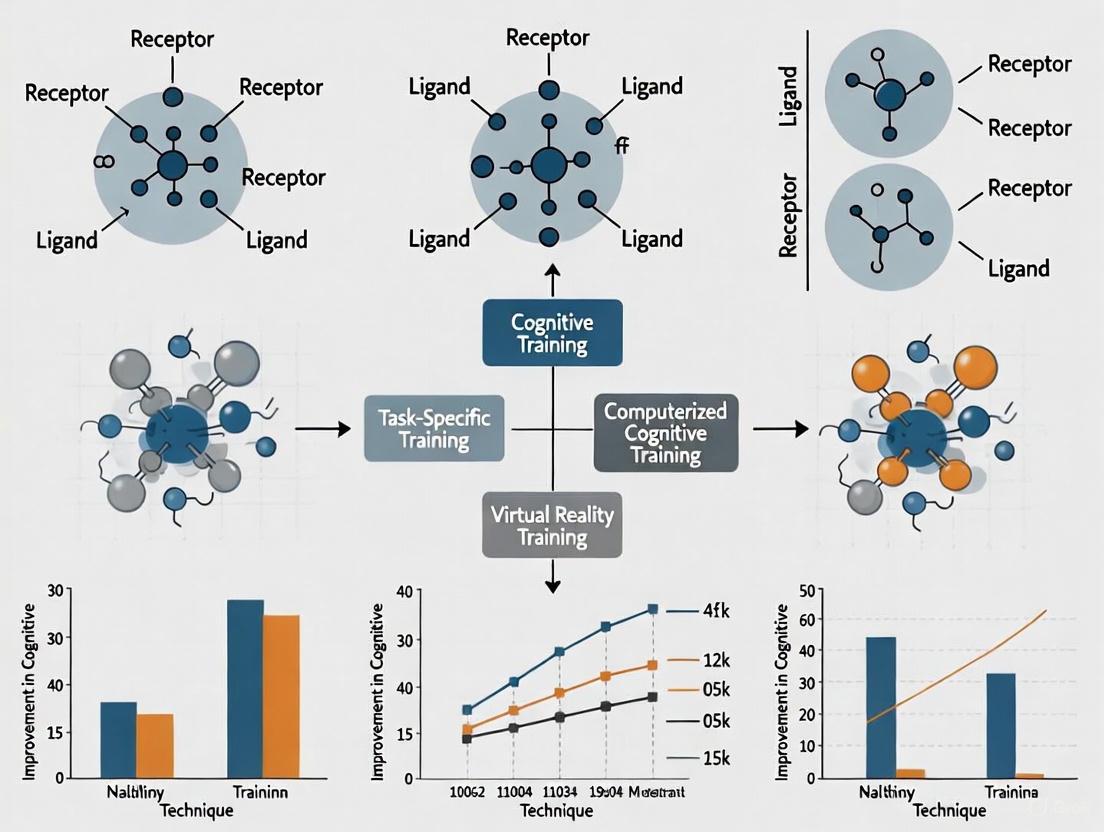

Comparative Efficacy of Cognitive Rehabilitation Approaches

Integrated Rehabilitation Methodologies

Several cognitive rehabilitation approaches have demonstrated efficacy in addressing PSCI, with combination therapies often showing superior results. Network meta-analyses reveal that working memory (WM) training combined with speech and language therapy (SLT) leads to significantly enhanced outcomes on the Western Aphasia Battery (WAB) Aphasia Quotient compared to SLT alone [3]. This combination was more effective than both computer-assisted cognitive training (CCT) with SLT and telerehabilitation computer-assisted cognitive training (tCCT) with SLT in improving WAB scores [3].

Additionally, virtual reality-based cognitive training (vrCT) combined with SLT significantly improved auditory comprehension compared with SLT alone [3]. Attention training (AT) combined with SLT also proved more effective than vrCT with SLT in enhancing spontaneous speech [3]. These findings suggest that while SLT remains a cornerstone of post-stroke cognitive rehabilitation, its efficacy is significantly enhanced when combined with specific cognitive training approaches, particularly working memory training and virtual reality-based interventions.

Advanced Interventions and Emerging Protocols

Innovative approaches combining cognitive rehabilitation with neuromodulation techniques represent the cutting edge of PSCI treatment. Research on cognitive remediation (CR) combined with repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation (rTMS) has shown promising results in improving cognitive functioning in stroke patients [4]. Similarly, speech therapy combined with multi-modality aphasia therapy and rTMS has demonstrated efficacy for chronic post-stroke non-fluent aphasia [4].

The mechanisms underlying these combined approaches involve neuroplasticity enhancement through synchronized neural activation. rTMS is thought to facilitate cortical excitability and strengthen functional connections in brain networks disrupted by stroke, potentially creating a more receptive state for cognitive training [4]. This synergistic effect between neuromodulation and cognitive training highlights the potential of mechanism-based interventions targeting the neurophysiological processes underlying recovery.

Cognitive Rehabilitation Pathway for PSCI

Experimental Protocols and Research Methodologies

Standardized Assessment Protocols

Research on PSCI employs rigorous assessment protocols to evaluate cognitive function and its impact on recovery. Standardized methodology includes the Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA) for global cognitive screening, which assesses multiple domains including visuospatial and executive skills, naming, attention, language, abstraction, delayed memory, and orientation [2]. For more detailed evaluation of specific cognitive domains, instruments such as the Western Aphasia Battery (WAB) are employed to measure spontaneous speech, auditory comprehension, repetition, and naming abilities [3].

Functional outcomes are typically assessed using performance-based measures and participant-reported instruments. The Activity Measure for Post-Acute Care (AM-PAC) evaluates basic mobility, daily activities, and applied cognition [2], while the Participation Measure-3 Domains, 4 Dimensions (PM-3D4D) captures social participation, community participation, and productivity across both frequency and perceived difficulty dimensions [2]. These standardized assessment protocols enable consistent measurement across studies and facilitate comparison of rehabilitation outcomes.

Intervention Protocols and Trial Methodologies

Randomized controlled trials (RCTs) investigating cognitive rehabilitation interventions follow rigorous methodological standards. The ESTREL trial methodology provides an exemplary model for pharmacological interventions in stroke recovery, utilizing a double-blind, placebo-controlled design with standardized rehabilitation therapy based on active task-oriented training [5]. This trial randomized 610 patients with acute ischemic or hemorrhagic stroke to receive either levodopa/carbidopa or placebo three times daily for 39 days alongside rehabilitation, with the primary outcome being the Fugl-Meyer Assessment score at 3 months [5].

For non-pharmacological interventions, network meta-analyses systematically compare multiple rehabilitation approaches. These studies follow PRISMA guidelines and Cochrane Handbook methodologies, searching multiple databases including PubMed, Embase, Cochrane Library, and regional databases [3] [4]. Quality assessment tools like the Methodological Evaluation of Observational REsearch (MORE) checklist evaluate observational studies on disease incidence or risk factors, analyzing external and internal validity through multiple items scored based on methodological flaws [6]. These rigorous methodologies ensure the validity and reliability of findings in cognitive rehabilitation research.

Table 4: Key Assessment Tools in PSCI Research

| Assessment Tool | Domains Measured | Application in PSCI |

|---|---|---|

| Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA) | Visuospatial and executive skills, naming, attention, language, abstraction, delayed memory, orientation | Global cognitive screening |

| Western Aphasia Battery (WAB) | Spontaneous speech, auditory comprehension, repetition, naming | Language-specific assessment |

| Activity Measure for Post-Acute Care (AM-PAC) | Basic mobility, daily activities, applied cognition | Functional ability measurement |

| Participation Measure-3 Domains, 4 Dimensions (PM-3D4D) | Social participation, community participation, productivity | Participation restriction assessment |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 5: Essential Research Materials and Assessment Tools

| Research Tool | Function/Application | Specific Utility in PSCI Research |

|---|---|---|

| Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA) | Brief cognitive screening tool | Assesses global cognitive function and specific cognitive domains |

| Western Aphasia Battery (WAB) | Comprehensive language assessment | Evaluates aphasia quotient and specific language domains |

| Fugl-Meyer Assessment (FMA) | Stroke-specific motor function measure | Primary outcome in motor recovery trials [5] |

| Activity Measure for Post-Acute Care (AM-PAC) | Functional activity measurement | Captures basic mobility, daily activities, and applied cognition |

| Participation Measure-3 Domains, 4 Dimensions (PM-3D4D) | Participation restriction assessment | Measures social, community, and productivity participation |

| Repetitive Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation (rTMS) | Non-invasive brain stimulation | Modulates cortical excitability to enhance neuroplasticity [4] |

| Virtual Reality (VR) Cognitive Training Systems | Immersive cognitive rehabilitation | Provides ecologically valid training environments [3] |

| Levodopa/Carbidopa | Dopaminergic medication | Investigated for enhancing neuroplasticity in stroke recovery [5] |

Standard Research Workflow in PSCI Trials

The epidemiology and clinical burden of post-stroke cognitive impairment present significant challenges in stroke rehabilitation, with approximately 70% of stroke survivors experiencing cognitive deficits that substantially impact their functional independence and quality of life. Domain-specific deficits in attention, executive functions, memory, and language demonstrate distinct associations with various functional outcomes, necessitating comprehensive assessment and targeted intervention strategies. Evidence supports the efficacy of integrated rehabilitation approaches, particularly working memory training combined with speech and language therapy, and virtual reality-based cognitive training, with emerging promise in neuromodulation techniques such as rTMS. Future research should focus on personalized cognitive rehabilitation protocols based on individual deficit profiles and stroke characteristics, while ongoing investigation into pharmacological adjuncts continues to seek effective interventions to enhance neuroplasticity and optimize recovery in PSCI.

Stroke remains a leading cause of long-term disability worldwide, with approximately 60% of survivors experiencing persistent cognitive impairments and only 12% achieving complete functional recovery after conventional physical therapy [7] [8]. The landscape of stroke rehabilitation is undergoing a paradigm shift, moving from traditional compensatory approaches toward therapies that actively promote brain repair by harnessing the brain's inherent neuroplastic capacity [7]. Neuroplasticity—the brain's ability to reorganize its structure, function, and connections in response to experience and injury—serves as the fundamental mechanism underlying functional recovery after stroke [9] [10]. This review adopts a comparative framework to evaluate emerging neuroplasticity-based interventions, with particular emphasis on Hebbian principles and endogenous repair processes, to provide researchers and drug development professionals with a critical analysis of their mechanisms, efficacy, and potential integration.

At the core of this discussion lies Hebb's seminal principle, often summarized as "cells that fire together, wire together," which proposes that synaptic connections are strengthened when pre- and postsynaptic neurons are repeatedly co-activated [11]. This concept provides the theoretical foundation for understanding how targeted interventions can remodel neural circuits after stroke [9] [12]. Meanwhile, the brain's endogenous repair mechanisms, including neurogenesis and structural reorganization, offer complementary pathways for recovery [7] [10]. The interplay between these targeted plasticity approaches and the brain's innate reparative capacity forms a rich therapeutic landscape for investigation, with timing, individual patient characteristics, and intervention specificity emerging as critical determinants of successful outcomes [9] [7].

Comparative Analysis of Neuroplasticity-Based Interventions

Hebbian Plasticity Approaches

Brain-Computer Interface with Functional Electrical Stimulation (BCI-FES) represents a technologically advanced application of Hebbian principles. This approach synchronizes motor cortical activity associated with movement attempts with precisely timed peripheral sensory feedback through FES, creating ideal conditions for Hebbian plasticity to strengthen corticomuscular connections [13]. In a 2024 clinical study comparing BCI-FES with randomly timed FES in subcortical stroke patients, the BCI-FES group demonstrated significantly greater improvements in Fugl-Meyer Assessment for Upper Extremity (FMA-UE) scores, increased motor evoked potential amplitudes, enhanced beta oscillatory power over contralateral motor cortex, and strengthened corticomuscular coherence [13]. These findings provide compelling evidence that temporally coincident pairing of cortical activation with peripheral feedback can effectively drive motor recovery by re-establishing functional connectivity between the brain and paralyzed limbs.

Paired Associative Stimulation (PAS), another Hebbian-based intervention, involves repeated pairing of peripheral nerve stimulation with transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS) of the corresponding motor cortex [9] [12]. The protocol capitalizes on spike-timing-dependent plasticity, where the precise temporal relationship between pre- and postsynaptic activation determines whether long-term potentiation (LTP)-like or long-term depression (LTD)-like plasticity is induced [9]. Research indicates that LTP-like plasticity is optimally induced when peripheral stimulation precedes TMS by approximately 25 milliseconds, while reversing this timing can induce LTD-like effects [9] [11]. A current clinical trial protocol (ChiCTR2000039949) aims to extend this principle by targeting the supplementary motor area (SMA) with TMS followed by peripheral magnetic stimulation of upper limb nerves to reconstruct the SMA→internal capsule→periphery neural circuit for arm motor recovery [12]. This innovative approach recognizes that stroke impairs entire brain networks rather than isolated regions, and aims to rebuild disrupted motor circuits instead of simply upregulating excitation in focal areas [12].

Transcranial Direct Current Stimulation (tDCS) has also demonstrated efficacy in modulating cortical excitability to enhance cognitive recovery. A recent systematic review of 22 randomized controlled trials involving 5,100 participants found that tDCS produced significant cognitive benefits as measured by Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA) scores, with a mean difference of 4.56 points compared to control groups [14]. The mechanism involves creating a favorable neurophysiological environment for plasticity by applying weak direct currents to modulate neuronal membrane potentials, thereby lowering the threshold for LTP induction when combined with cognitive training [14].

Table 1: Comparative Outcomes of Hebbian-Based Interventions for Stroke Recovery

| Intervention | Mechanism of Action | Primary Outcome Measures | Efficacy Evidence | Optimal Timing |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| BCI-FES | Synchronizes EEG-detected movement attempts with FES-generated proprioceptive feedback | FMA-UE, Corticomuscular coherence, MEP amplitude | Significantly greater FMA-UE improvement vs. random FES (p=0.030) [13] | Acute/Subacute phase [13] |

| PAS | Pairs peripheral nerve stimulation with TMS of motor cortex | WMFT, FMA-UE, FIM, fNIRS parameters | Clinical trials ongoing; preclinical data shows enhanced corticospinal excitability [9] [12] | Chronic phase [12] |

| tDCS | Modulates cortical excitability via weak direct currents | MoCA, Cognitive domain scores | MD 4.56 on MoCA (95% CI: 3.19-5.93) [14] | Early intervention (<3 months) [14] |

Endogenous Repair Approaches

The brain possesses remarkable intrinsic capacity for self-repair through processes collectively termed endogenous repair mechanisms. Stroke-induced neurogenesis represents a key component of this innate recovery system, involving the proliferation of neural stem cells primarily from the subventricular zone (SVZ) and their migration to infarct and peri-infarct regions, where they differentiate into functional neurons [10]. This complex process is regulated by numerous molecular factors including Fibroblast Growth Factor-2 (FGF-2), Insulin-like Growth Factor-1 (IGF-1), Brain-Derived Neurotrophic Factor (BDNF), and Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor (VEGF), which promote neural stem cell proliferation [10]. Additionally, Stromal-derived factor (SDF-1), Monocyte Chemoattractant Protein (MCP-1), and Matrix Metalloproteinases (MMPs) facilitate neuroblast migration to damaged areas [10].

The neuroinflammatory response plays a dual role in modulating endogenous repair processes. While chronic neuroinflammation is generally detrimental to recovery, acute inflammatory responses can promote neurogenesis through specific cytokine signaling [10]. For instance, short-term interleukin-6 (IL-6) exposure induces neurogenesis in vitro, whereas chronic IL-6 expression reduces neurogenesis in the dentate gyrus [10]. Similarly, interleukin-1α (IL-1α) demonstrates neurogenic properties, while IL-1β primarily contributes to neural clearance [10]. Microglia and astrocytes further modulate this process through the release of trophic factors that support neural stem cell migration and differentiation, though their activated states can also impede neuronal survival [10].

Pharmacological approaches targeting endogenous repair mechanisms are emerging as promising therapeutic strategies. A recent systematic review found that pharmacological interventions produced robust cognitive improvements post-stroke, with a mean difference of 4.00 points on MoCA scores (95% CI: 3.48-4.52) [14]. Of particular interest are psychoplastogens—compounds that promote neuronal structural plasticity. Tabernanthalog (TBG), a nonhallucinogenic psychoplastogen, has been shown to promote cortical neuroplasticity through 5-HT2A, TrkB, mTOR, and AMPA receptor activation, similar to classic psychedelics, but without inducing immediate early gene activation or hallucinogenic effects [15]. This mechanism represents a novel approach to enhancing the brain's inherent plastic capacity through pharmacological modulation.

Table 2: Endogenous Repair Mechanisms and Their Modulators

| Endogenous Process | Key Molecular Mediators | Therapeutic Modulation | Functional Impact |

|---|---|---|---|

| Neural Stem Cell Proliferation | FGF-2, IGF-1, BDNF, VEGF [10] | Pharmacological enhancement of trophic factors | Increased neural stem cell population in neurogenic niches |

| Neuroblast Migration | SDF-1, MCP-1, MMPs 2/3/9 [10] | Modulation of chemokine signaling | Directed migration to ischemic regions |

| Neuronal Differentiation & Maturation | Perlecan domain V, PTX-3 [10] | Extracellular matrix remodeling | Enhanced maturation and functional integration of new neurons |

| Structural Plasticity | 5-HT2A, TrkB, mTOR, AMPA receptors [15] | Nonhallucinogenic psychoplastogens (e.g., TBG) | Increased cortical spinogenesis and neurite extension |

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

BCI-FES Protocol for Upper Limb Rehabilitation

The BCI-FES intervention described in the 2024 study employs a sophisticated protocol for retraining corticomuscular connections [13]. The methodology begins with high-density electroencephalography (EEG) recording during cued movement attempts and rest periods to identify optimal features for classification. Electrode locations and spectral power frequencies that demonstrate the greatest differences between movement and rest states are selected as features for training a classifier to detect movement attempts in real-time [13]. The sensorimotor rhythm, particularly event-related desynchronization in alpha (8-12 Hz) and beta (13-30 Hz) frequency bands, provides the primary input signal for the BCI [13].

During treatment sessions, patients perform attempted movements of the affected limb, while the BCI system continuously monitors EEG signals. When the classifier detects features associated with movement attempts, it immediately triggers functional electrical stimulation (FES) to the corresponding paralyzed muscles, generating coordinated movement and associated proprioceptive feedback [13]. This creates precisely timed coincidence between top-down motor commands and bottom-up sensory inputs, ideal for inducing Hebbian plasticity [13]. The treatment typically involves multiple sessions per week over several weeks, with regular re-calibration of the classifier to adapt to changing neural patterns as recovery progresses [13]. Notably, feature selection evolves during the treatment course, typically shifting from bilateral to increasingly ipsilesional dominance, reflecting functional reorganization of motor networks [13].

Paired Associative Stimulation Protocol

The cortico-peripheral Hebbian-type stimulation protocol targets reconstruction of damaged motor circuits through carefully timed paired stimulation [12]. The procedure involves transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS) of the supplementary motor area (SMA) followed by peripheral magnetic stimulation (PMS) of the peripheral nerves innervating the affected upper limb [12]. The temporal interval between cortical and peripheral stimulation is critical, typically set to tens of milliseconds, to capitalize on spike-timing-dependent plasticity rules [12].

This randomized controlled trial protocol administers one session of real or sham Hebbian-type stimulation daily, five days per week, for a total of 25 sessions, always followed by conventional rehabilitation therapy [12]. Outcome measures assessed at baseline, post-treatment, and 3-month follow-up include the Wolf Motor Function Test (WMFT) as the primary outcome, with Fugl-Meyer Assessment for Upper Extremity (FMA-UE), Functional Independence Measure (FIM), and functional near-infrared spectroscopy (fNIRS) parameters as secondary outcomes [12]. The fNIRS component enables investigation of neural correlates of recovery, particularly changes in cortical activation patterns during motor tasks [12].

Diagram Title: BCI-FES Hebbian Plasticity Protocol

Assessing Endogenous Neurogenesis

Experimental investigation of stroke-induced neurogenesis employs specialized methodologies to track and quantify the birth, migration, and integration of new neurons [10]. The gold standard approach involves brdU labeling, where bromodeoxyuridine (BrdU), a thymidine analog, is incorporated into the DNA of dividing cells during the S-phase, allowing histological identification of newly generated cells [10]. Following BrdU administration, immunohistochemical techniques using antibodies against BrdU combined with neuronal markers such as NeuN, doublecortin, or βIII-tubulin enable specific identification of newly generated neurons [10].

Additional methodologies include retroviral labeling of neural stem cells to track their fate and transgenic reporter models that express fluorescent proteins under the control of neural stem cell-specific promoters [10]. To assess functional integration, optogenetic and chemogenetic approaches allow selective activation or inhibition of newborn neurons, while serial in vivo imaging through cranial windows enables direct visualization of neuronal migration and structural maturation over time [10]. Behavioral tests sensitive to hippocampal-dependent learning (e.g., Morris water maze, contextual fear conditioning) and motor function (e.g., ladder rung walking, pellet retrieval) provide functional correlates of successful neurogenesis and integration [10].

Molecular Mechanisms of Hebbian and Homeostatic Plasticity

At the molecular level, Hebbian plasticity involves sophisticated signaling cascades that translate coordinated neuronal activity into lasting synaptic changes. The NMDA receptor serves as a critical coincidence detector, requiring simultaneous presynaptic glutamate release and postsynaptic depolarization to relieve magnesium blockade and permit calcium influx [11]. This calcium influx triggers activation of calcium/calmodulin-dependent kinase II (CaMKII), which phosphorylates AMPA receptors to increase their conductivity and promotes their insertion into the postsynaptic density, thereby strengthening synaptic transmission [11].

For longer-lasting plasticity, calcium signaling activates cAMP-dependent kinase (PKA) and downstream transcription factors such as CREB, which induce expression of plasticity-related genes including BDNF, Arc, and Homer1a [11]. The synaptic tagging and capture hypothesis provides a framework for understanding how transient synaptic activity can be stabilized into persistent changes, wherein stimulated synapses generate a "tag" that captures plasticity-related proteins synthesized in response to strong stimulation [11].

Structural correlates of Hebbian plasticity include dendritic spine enlargement and the formation of new synaptic connections, processes mediated by reorganization of the actin cytoskeleton and membrane insertion of adhesion molecules [11]. Conversely, long-term depression (LTD) involves different signaling pathways, including activation of protein phosphatases and internalization of AMPA receptors, resulting in synaptic weakening [11].

Diagram Title: Molecular Mechanisms of Hebbian Plasticity

Homeostatic plasticity mechanisms provide crucial negative feedback to prevent runaway excitation and maintain neural circuit stability [9]. These include synaptic scaling, wherein neurons globally adjust synaptic strengths in response to chronic changes in activity levels, and metaplasticity, which refers to activity-dependent changes in the ability to induce subsequent plasticity [9]. The Bienenstock-Cooper-Munro (BCM) theory provides a conceptual framework for understanding how the threshold for LTP/LTD induction shifts according to prior synaptic activity [9]. From a therapeutic perspective, homeostatic mechanisms necessitate careful consideration of intervention timing and sequence, as facilitatory priming can sometimes diminish the effects of subsequent therapies [9].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Methodologies

Table 3: Essential Research Tools for Investigating Post-Stroke Neuroplasticity

| Tool/Reagent | Application | Function in Research | Example Use Cases |

|---|---|---|---|

| High-density EEG Systems | Recording cortical oscillatory activity | Detects movement attempt-related ERD/ERS patterns for BCI control [13] | Real-time classification of movement intention for triggered FES |

| Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation (TMS) | Non-invasive brain stimulation | Assesses corticospinal excitability via MEPs; induces plasticity in therapeutic protocols [9] [12] | Paired associative stimulation; mapping cortical reorganization |

| Functional NIRS (fNIRS) | Monitoring cortical activation | Measures hemodynamic responses during motor tasks; assesses intervention effects [12] | Evaluating SMA activation changes after Hebbian-type stimulation |

| BrdU and Neural Markers | Tracking neurogenesis | Labels newly generated cells; identifies neuronal differentiation [10] | Quantifying stroke-induced neurogenesis in neurogenic niches |

| Psychoplastogens (e.g., TBG) | Promoting structural plasticity | Induces neurite growth and spinogenesis without hallucinogenic effects [15] | Enhancing structural basis for functional recovery |

| Cytokine Modulators | Regulating neuroinflammation | Manipulates neuroinflammatory environment to favor neurogenesis [10] | Shifting microglial phenotype from detrimental to supportive |

Comparative Efficacy and Clinical Translation

When comparing neuroplasticity-based interventions, several key patterns emerge regarding their efficacy and optimal application. Timing represents a critical factor, with most interventions showing enhanced effectiveness when initiated early after stroke [7] [14]. The traditional view that recovery plateaus by 6 months is being challenged by evidence showing that the restorative window may be much longer than previously thought, with the optimal time for brain repair potentially occurring at later stages rather than earlier [7]. Nevertheless, early intervention (within 3 months post-stroke) generally produces the most robust outcomes, possibly due to heightened plasticity during this period [14].

The intervention specificity also significantly influences outcomes. BCI-FES demonstrates particular efficacy for motor recovery by directly targeting the disrupted corticomuscular pathways [13]. In contrast, tDCS shows broader effects on cognitive function, likely through creating a generally permissive environment for plasticity across multiple cognitive domains [14]. Pharmacological approaches such as psychoplastogens operate at a more fundamental level by enhancing the structural basis for plasticity throughout affected networks [15].

For successful clinical translation, combination approaches that simultaneously target multiple recovery mechanisms hold particular promise [9] [7]. However, combining interventions requires careful consideration of homeostatic metaplasticity, as improper timing can diminish rather than enhance efficacy [9]. The future of stroke rehabilitation likely lies in personalized protocols that account for individual lesion characteristics, residual network connectivity, and specific functional deficits, ultimately leveraging both targeted Hebbian plasticity and enhanced endogenous repair processes to maximize recovery [9] [7] [10].

The comparative analysis of neuroplasticity-based interventions reveals a dynamic and rapidly evolving therapeutic landscape for stroke recovery. Hebbian principles provide a powerful framework for designing targeted therapies that selectively strengthen behaviorally relevant neural connections, while endogenous repair processes offer complementary pathways for structural restoration of damaged neural networks [9] [10]. The most promising future directions involve strategic integration of these approaches, leveraging their synergistic potential while carefully managing timing considerations to avoid homeostatic interference [9].

For researchers and drug development professionals, this analysis highlights several priority areas. First, advancing personalization through improved biomarker identification could enable better matching of interventions to individual patient characteristics and lesion profiles [13] [14]. Second, refining temporal parameters for combination therapies may maximize efficacy while minimizing homeostatic limitations [9]. Third, developing novel pharmacologic approaches that enhance both targeted plasticity and endogenous repair processes represents a promising frontier, with nonhallucinogenic psychoplastogens such as TBG offering particularly intriguing possibilities [15]. As our understanding of the complex interplay between different plasticity mechanisms deepens, so too will our ability to design increasingly effective, multidimensional interventions that harness the brain's remarkable capacity for change and restoration after stroke.

The comparative analysis of cognitive rehabilitation techniques in stroke research increasingly focuses on understanding molecular mechanisms that drive neuroplasticity and functional recovery. Among these, Brain-Derived Neurotrophic Factor (BDNF) and cholinergic pathways emerge as critical systems with distinct yet complementary roles. BDNF, the most abundant neurotrophin in the adult brain, facilitates synaptic plasticity, neuronal survival, and cognitive processes, while cholinergic systems, originating from basal forebrain nuclei, regulate attention, learning, and memory formation. Evidence indicates that both systems undergo significant alterations following stroke, making them promising therapeutic targets for cognitive rehabilitation. This review systematically compares these key neurotransmitter systems and growth factors, evaluating their mechanistic contributions, response to interventions, and potential as biomarkers for post-stroke cognitive recovery.

BDNF: Mechanisms and Experimental Evidence in Cognitive Recovery

Molecular Signaling and Pathophysiological Role

BDNF functions as a primary mediator of activity-dependent plasticity in the central nervous system. It is initially synthesized as a precursor protein (proBDNF) before proteolytic cleavage yields mature BDNF (mBDNF). These forms elicit opposing biological effects: mBDNF preferentially binds tropomyosin-related kinase B (TrkB) receptors, promoting neuronal survival, synaptic strengthening, and long-term potentiation (LTP), whereas proBDNF binding to p75 neurotrophin receptor (p75NTR) facilitates apoptosis and long-term depression [16] [17]. The BDNF gene contains a functional polymorphism (Val66Met) that affects activity-dependent secretion and is associated with structural and functional differences in brain regions critical for memory, including the hippocampus and prefrontal cortex [16].

In the context of stroke, BDNF signaling confers neuroprotection through multiple downstream pathways. Upon binding TrkB, BDNF activates phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K)/Akt and mitogen-activated protein kinase/extracellular signal-regulated kinase (MAPK/ERK) cascades, which inhibit apoptotic machinery and support cell survival [18]. Additionally, BDNF enhances synaptic transmission by regulating NMDA receptor trafficking and phosphorylation, and promotes dendritic spine complexity, thereby facilitating synaptic consolidation and memory formation [16] [19]. Notably, serum and cerebrospinal fluid BDNF levels are significantly reduced in stroke patients compared to healthy controls, with this reduction correlating with poorer functional and cognitive outcomes [20].

Supporting Experimental Data and Protocols

Table 1: Key Experimental Findings on BDNF in Stroke Recovery

| Study Model | Intervention | Key Findings | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Human Subjects (Meta-analysis) | Analysis of 62 studies (1,856 patients) | Significantly lower BDNF levels in stroke patients vs. healthy controls (SMD: -1.04); Depression further decreased BDNF (SMD: -0.60) | [20] |

| Mouse MCAO Model | Shuxuening injection (SXNI) | Reversed stroke-induced BDNF/TrkB expression decreases in hippocampal CA3; Activated neurotrophin/TrkB signaling (15 DEGs) | [21] |

| Rat Forebrain Ischemia | Exogenous BDNF administration | Improved long-term potentiation and cognitive functions in water maze tests | [22] |

| Human RCT (STROKEWALK) | SMS-guided physical exercise | Plasma BDNF levels analyzed as primary outcome; Correlation with improved walking performance | [23] |

Representative Experimental Protocol: Measuring Circulating BDNF Levels

- Specimen Collection: Non-fasting blood samples collected in heparinized vials at hospital admission and during follow-up (e.g., 3 months post-stroke). Plasma separated via centrifugation and stored at -80°C until analysis [23].

- BDNF Quantification: Total BDNF levels measured using DuoSet ELISA kit (DY248, R&D Systems). Plasma samples diluted 10x in reagent diluent (1% BSA in PBS). Detection system utilizes alkaline phosphatase (1:10,000; Roche Diagnostics) incubated for 2 hours at room temperature [23].

- Data Acquisition: Absorbance read kinetically at 405nm every 5 minutes for 1 hour using a spectrophotometer (e.g., Infinite M1000, Tecan). Samples measured in triplicate, with mean values calculated for analysis [23].

Cholinergic Pathways: Mechanisms and Experimental Evidence in Cognitive Recovery

Neuroanatomy and Pathophysiological Role

The basal forebrain cholinergic system constitutes a key network for cognitive function, comprising several nuclei: the medial septal nucleus (Ch1), the vertical and horizontal limbs of the diagonal band of Broca (Ch2, Ch3), and the nucleus basalis of Meynert (Ch4) [24]. These nuclei provide widespread cholinergic innervation to the hippocampus, cortex, and amygdala, regulating arousal, attention, learning, and memory. The cholinergic signaling molecule, acetylcholine (ACh), is synthesized by choline acetyltransferase (ChAT) and degraded by acetylcholinesterase (AChE) and butyrylcholinesterase (BChE) [23] [25].

Following neurological insults like stroke or traumatic brain injury, the cholinergic system demonstrates a biphasic response: an initial surge in ACh release is followed by persistent cholinergic hypofunction. Acute excess ACh contributes to excitotoxicity, while chronic deficiency underlies cognitive impairments [25]. Postmortem studies in dementia patients reveal substantial neuronal loss (up to 90-95%) in the basal forebrain accompanied by markedly reduced cortical acetylcholine activity [24]. Cholinergic degeneration is associated with deficits in multiple cognitive domains, with specific subregions having distinct roles—Ch1/2 atrophy correlates with episodic memory deficits, while Ch4 degeneration predicts attention and visuospatial decline [24].

Supporting Experimental Data and Protocols

Table 2: Key Experimental Findings on Cholinergic Pathways in Brain Disorders

| Study Model | Intervention/Assessment | Key Findings | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Human AD Continuum (n=100) | Free-water imaging (DTI-MRI) | FWf in Ch1-3 & Ch4 increased in aMCI/AD; Correlated with visuospatial/executive deficits (R=-0.47) | [24] |

| Human Stroke RCT (STROKEWALK) | SMS-guided physical exercise | Plasma ChAT activity and BChE activity measured as secondary outcomes; Cholinergic index calculated | [23] |

| TBI Animal Models | Scopolamine administration | Acute administration: neuroprotective; Chronic administration: enhanced ACh release in hippocampus | [25] |

| Vascular Dementia | Cholinergic agents | Cholinergic system vulnerability to vascular damage; Deficiency contributes to memory loss | [19] |

Representative Experimental Protocol: Analyzing Cholinergic Markers

- ChAT Activity Assay: Plasma samples diluted 300x in dilution buffer (10 mM TBS, 0.05% Triton X-100, 1 mM EDTA, pH 7.4). Native and heat-denatured samples plated in 384-well plates. Reaction initiated with cocktail A containing coenzyme-A, phosphotransacetylase, lithium potassium acetyl-phosphate, choline chloride, and eserine hemisulfate. After 1h incubation at 38°C, cocktail B added (choline oxidase, Streptavidin-HRP, 4-aminoantipyrine, phenol). Absorbance read at 500nm for 1h. ChAT activity calculated from choline standard curve [23].

- BChE Activity Assay: Plasma samples diluted 400x in dilution buffer. Samples mixed with master mix containing butyrylthiocholine iodide, DTNB, and specific AChE inhibitor BW280C51. Absorbance read immediately to measure enzymatic activity [23].

- Free-Water Imaging: Advanced DTI-MRI technique estimating extracellular water content to detect microstructural damage in cholinergic pathways. FWf increases reflect neuroinflammation or neurodegeneration in basal forebrain cholinergic structures [24].

Comparative Analysis: BDNF vs. Cholinergic Systems

Mechanistic Comparison

Table 3: Comparative Mechanisms of BDNF and Cholinergic Systems in Cognitive Recovery

| Parameter | BDNF System | Cholinergic System |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Functions | Synaptic plasticity, neuronal survival, LTP, neurogenesis | Attention, learning, memory, arousal, sensory processing |

| Cellular Receptors | TrkB, p75NTR | Muscarinic (M1-M5), Nicotinic receptors |

| Response to Injury | Acute upregulation (neuroprotective), then chronic depletion | Acute excitotoxic surge, then chronic hypofunction |

| Recovery Mechanisms | Promotes synaptic reorganization, dendritic spine growth | Enhances cortical plasticity, attentional modulation |

| Therapeutic Targeting | Exercise, antidepressants, BDNF mimetics, stem cells | Acetylcholinesterase inhibitors, muscarinic/nicotinic agonists |

| Biomarker Potential | Circulating BDNF levels predict recovery and treatment response | Cholinergic basal forebrain integrity via free-water imaging |

Therapeutic Implications and Research Gaps

Both BDNF and cholinergic systems present promising but distinct therapeutic avenues for cognitive rehabilitation. Physical exercise robustly enhances BDNF signaling and represents a potent non-pharmacological intervention, with meta-analyses confirming its immediate positive effect on BDNF levels (SMD: 0.49) [20]. Similarly, cholinergic stimulation via acetylcholinesterase inhibitors (e.g., donepezil, rivastigmine) demonstrates benefits in vascular dementia and post-stroke cognitive impairment [25] [19]. However, several research gaps remain, including optimal timing for interventions (acute vs. chronic phases), differential effects across stroke subtypes, and potential synergistic effects of combining BDNF-enhancing and cholinergic therapies.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Methodologies

Table 4: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Investigating BDNF and Cholinergic Systems

| Reagent/Method | Application | Experimental Function | Example Specifications |

|---|---|---|---|

| BDNF ELISA Kits | BDNF quantification | Measures total BDNF levels in plasma, serum, CSF | DuoSet ELISA (DY248, R&D Systems) [23] |

| ChAT Activity Assay | Cholinergic function | Measures enzymatic activity of choline acetyltransferase | Custom assay with choline oxidase-based detection [23] |

| BChE Activity Assay | Cholinergic function | Measures butyrylcholinesterase activity | DTNB-based colorimetric assay with AChE inhibition [23] |

| Free-Water Imaging (DTI-MRI) | Cholinergic pathway integrity | Assesses microstructural damage in basal forebrain | 3.0T Siemens scanner with DTI sequences [24] |

| Six-Minute Walk Test (6MWT) | Functional assessment | Evaluates walking performance as functional outcome | 30-meter course, maximum speed [23] |

| MoCA Assessment | Cognitive evaluation | Comprehensive cognitive domain testing | Beijing version for Chinese populations [24] |

Signaling Pathway Visualizations

Diagram 1: BDNF Signaling Pathway. This visualization illustrates the dual pathways of proBDNF and mature BDNF, highlighting their opposing effects on neuronal survival and synaptic plasticity through distinct receptor interactions.

Diagram 2: Cholinergic Signaling Pathway. This diagram outlines acetylcholine synthesis, receptor interactions, and degradation pathways central to cognitive function.

This comparative analysis elucidates the distinct yet interconnected roles of BDNF and cholinergic systems in post-stroke cognitive recovery. While BDNF primarily modulates synaptic plasticity and neuronal survival through tropomyosin-related kinase signaling, cholinergic pathways predominantly regulate attentional processes and cortical plasticity via muscarinic and nicotinic receptors. Both systems demonstrate characteristic perturbations following neurological injury and represent validated targets for therapeutic intervention. Future research should prioritize combinatorial approaches that simultaneously engage both systems, optimize timing for interventions across recovery phases, and validate multimodal biomarkers for patient stratification and treatment monitoring. The continued refinement of experimental methodologies, including advanced imaging techniques and molecular assays, will further delineate the therapeutic potential of these critical neurotransmitter systems and growth factors in cognitive rehabilitation.

In the field of stroke rehabilitation, two principal philosophical approaches guide therapeutic interventions: restorative and compensatory strategies. These approaches represent fundamentally different conceptions of recovery after neurological injury. Restorative strategies aim to retrain, strengthen, and restore impaired cognitive functions through direct, repetitive practice, operating on the principle of experience-dependent neuroplasticity whereby targeted stimulation can promote reorganization of neural circuits [26] [27]. In contrast, compensatory strategies focus on developing alternative methods to accomplish functional goals despite persistent cognitive deficits, often through environmental modifications, assistive devices, or strategy training [28] [27]. The choice between these approaches—or their strategic integration—forms the cornerstone of personalized neurorehabilitation plans in stroke recovery, requiring clinicians and researchers to understand their distinct theoretical foundations, mechanisms, and evidence bases.

This comparative analysis examines the theoretical underpinnings, methodological applications, and empirical support for both restorative and compensatory rehabilitation paradigms within stroke research. We present structured comparisons of quantitative outcomes, detailed experimental protocols, and analytical frameworks to guide evidence-based practice and future research directions in cognitive rehabilitation.

Theoretical Foundations and Conceptual Frameworks

The restorative and compensatory approaches originate from different theoretical models of how the brain responds to injury and achieves functional improvement. Understanding these foundational principles is essential for appropriate application and research design.

Restorative Rehabilitation: Theoretical Basis

Restorative approaches are predominantly grounded in the principles of neuroplasticity—the brain's inherent capacity to reorganize its structure and function in response to experience. The core hypothesis posits that targeted, repetitive cognitive activity can stimulate cortical reorganization, potentially restoring damaged neural pathways or engaging peri-lesional areas to support recovered function [26] [27]. Key theoretical elements include:

- Experience-Dependent Plasticity: Neural circuits can be modified through intense, specific training experiences, leading to strengthened synaptic connections [26].

- Task-Specific Training: Recovery is optimized when training closely mirrors the targeted cognitive domain, promoting specific neural adaptations [26].

- Massed Practice: High-intensity, repetitive practice is necessary to drive neural reorganization and consolidation of learning [29].

Modern restorative interventions often incorporate advanced technologies including computerized cognitive training, virtual reality, and brain-computer interfaces to deliver precisely controlled, engaging training environments that can be systematically progressed in difficulty [26].

Compensatory Rehabilitation: Theoretical Basis

Compensatory approaches stem from a different conceptual model that emphasizes functional adaptation rather than neurological restoration. The fundamental premise is that individuals can achieve functional goals through alternative means when impaired functions cannot be fully restored. Theoretical foundations include:

- Ecological Models: Focus on improving performance in real-world contexts through adaptation of tasks or environments [28].

- Behavioral Compensation: Development of new behavioral strategies to circumvent cognitive impairments [28] [27].

- Environmental Adaptation: Modifying the physical or social environment to reduce cognitive demands [28].

Compensatory approaches include external aids (e.g., calendars, smartphones), internal strategies (e.g., mnemonics, self-talk), and environmental modifications (e.g., reducing distractions, labeling cabinets) [28] [27]. These strategies acknowledge persistent deficits while focusing on maximizing functional independence and participation.

The following conceptual diagram illustrates the theoretical pathways and mechanisms differentiating these approaches:

Figure 1: Theoretical Pathways of Restorative and Compensatory Rehabilitation. This diagram illustrates the distinct mechanisms through which restorative (blue) and compensatory (green) approaches operate following stroke injury, with the potential for integrated application (yellow).

Comparative Efficacy: Quantitative Analysis of Outcomes

Empirical evidence for both restorative and compensatory approaches varies across cognitive domains and severity levels of stroke-related impairment. The tables below synthesize quantitative findings from systematic reviews and clinical studies, providing a comparative analysis of outcomes.

Table 1: Efficacy of Restorative Cognitive Rehabilitation After Stroke

| Cognitive Domain | Intervention Type | Outcome Measures | Effect Size (SMD/OR) | Evidence Quality | Key References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Basic ADLs | Domain-specific retraining | Barthel Index, FIM | SMD 0.48 (95% CI: -0.04 to 1.01) | Very low | [30] |

| Instrumental ADLs | Executive function training | IADL scales | SMD -0.19 (95% CI: -0.65 to 0.27) | Moderate | [30] |

| Global Cognition | Computerized training | MMSE, MoCA | Variable effects | Low to moderate | [26] |

| Attention | Attention process training | Reaction time, accuracy | 15-20% improvement in processing speed | Moderate | [26] |

| Executive Function | Strategy-based training | Wisconsin Card Sort, Trail Making | Hedges' g = 0.48 (p < 0.01) | Moderate | [26] |

Table 2: Efficacy of Compensatory Cognitive Rehabilitation After Stroke

| Strategy Category | Specific Techniques | Targeted Limitations | Functional Improvement | Evidence Support | Key References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Assistive Devices | Memory aids, smart technology | Memory, executive function | Enhanced independence perceptions | Strong | [28] |

| Method Modification | Task sequencing, time management | Executive function, attention | Maintained engagement in activities | Moderate | [28] |

| Frequency Adjustment | Activity reduction, pacing | Fatigue, processing speed | Associated with depressed mood | Mixed | [28] |

| Human Assistance | Caregiver support, supervision | Multiple domains | Context-dependent acceptability | Variable | [28] |

| Environmental Adaptation | Workspace modification, signage | Attention, executive function | Reduced environmental demands | Moderate | [27] |

Table 3: Comparative Predictors of Treatment Response

| Factor | Restorative Approach | Compensatory Approach | Clinical Implications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Time Post-Stroke | More effective in early phase (<6 months) | Effective across all phases | Timing influences approach selection |

| Severity of Impairment | Mild to moderate deficits | All severity levels, including severe | Severe deficits may favor compensation |

| Cognitive Domain | Attention, executive function | Memory, executive function | Domain-specific efficacy patterns |

| Neuroimaging Findings | Greater cortical reserve | Integrity of alternative networks | Biomarker-guided prescription |

| Patient Preferences | High self-efficacy, internal locus | Practical, immediate solutions | Engagement and adherence considerations |

Experimental Protocols and Methodological Considerations

Robust experimental design is essential for evaluating the efficacy of rehabilitation approaches. Below we detail standardized protocols for investigating restorative and compensatory interventions in stroke research.

Restorative Training Experimental Protocol

Objective: To determine the effect of process-specific cognitive retraining on neuropsychological function and daily living outcomes.

Population: Adults with first-ever stroke (3-12 months post-injury) with documented cognitive impairment in targeted domains.

Intervention Protocol:

- Frequency/Duration: 60-minute sessions, 3-5 times/week for 12 weeks

- Progression: Hierarchical difficulty adjustment maintaining 80% accuracy

- Core Components:

- Massed Practice: High-intensity, repetitive drills targeting specific cognitive domains

- Feedback: Continuous performance feedback with reinforcement

- Generalization: Progressive transfer of skills to ecologically relevant tasks

Control Conditions: Active control (non-specific cognitive activities) or standard care

Outcome Measures:

- Primary: Standardized cognitive tests targeting trained domains

- Secondary: Functional capacity measures (e.g., ADL scales), neuroimaging (fMRI, EEG)

- Follow-up: 3, 6, and 12 months post-intervention

Table 4: Research Reagent Solutions for Cognitive Rehabilitation Studies

| Reagent/Resource | Primary Function | Application Context | Example Products/Protocols |

|---|---|---|---|

| Computerized Cognitive Training Platforms | Delivery of standardized, adaptive restorative exercises | Restorative trials, home-based training | Cogmed, BrainHQ, RehaCom |

| Virtual Reality Systems | Immersive environment for ecologically valid assessment and training | Transfer evaluation, motivational enhancement | BTS NIRVANA, VRADL System |

| Standardized Neuropsychological Batteries | Objective measurement of cognitive change across domains | Outcome assessment, baseline characterization | RBANS, CNS-VS, NEPSY-II |

| Functional Assessment Tools | Measurement of real-world functional impact | Primary outcomes, ecological validity | FIM, Barthel Index, ADL Profile |

| Neuroimaging Acquisition & Analysis | Quantification of neural changes associated with recovery | Mechanism investigation, biomarker identification | fMRI, DTI, ERP protocols |

| Ecological Momentary Assessment | Real-world monitoring of cognitive function | Compensation utilization, treatment generalization | Smartphone-based EMA apps |

Compensatory Strategy Training Protocol

Objective: To evaluate the efficacy of systematic compensatory strategy training on functional independence.

Population: Stroke survivors with persistent cognitive deficits affecting daily functioning.

Intervention Protocol:

- Structured Training: Progressive introduction of compensatory strategies

- Strategy Categories:

- External Aids: Calendars, smartphones, alarms, organizers

- Internal Strategies: Mnemonics, self-instruction, visualization

- Environmental Modifications: Organized workspaces, reduction of distractions

- Generalization Training: Gradual application to real-world contexts with fading support

Active Ingredients: Strategy instruction, guided practice, problem-solving training, environmental support

Outcome Measures:

- Primary: Performance-based functional measures (e.g., Executive Function Performance Test)

- Secondary: Strategy use frequency, perceived effectiveness, caregiver burden

- Ecological Validity: Real-world task performance in home environment

The following workflow diagram illustrates the implementation sequence for a comprehensive rehabilitation trial:

Figure 2: Experimental Workflow for Comparative Rehabilitation Trials. This diagram outlines a methodological framework for investigating restorative versus compensatory approaches, highlighting key components including randomization, active controls, and blinded outcome assessment.

Research Gaps and Future Directions

Despite growing evidence in cognitive rehabilitation, significant methodological challenges and knowledge gaps remain. Recent systematic reviews highlight that descriptions of intervention protocols are frequently insufficient, restricting understanding, replication, and implementation of evidence-based cognitive rehabilitation [29]. Specifically, reporting of intervention "active ingredients" occurs in approximately only 50% of studies, with inadequate description of who provided interventions, specific procedures, and tailoring methods [29].

Future research priorities include:

- Longitudinal Studies: Investigation of long-term treatment effects and optimal timing for different approaches

- Personalized Medicine: Identification of biomarkers and clinical predictors to match patients with optimal interventions

- Combined Interventions: Systematic evaluation of integrated restorative-compensatory approaches

- Technology-Enhanced Methods: Development of accessible, engaging rehabilitation technologies including virtual reality and tele-rehabilitation [26]

- Implementation Science: Strategies to overcome barriers to clinical adoption of evidence-based protocols

The field would benefit from consistent application of reporting guidelines such as the TIDieR checklist to enhance methodological transparency and clinical implementation [29].

Both restorative and compensatory approaches offer valuable, complementary pathways for cognitive rehabilitation following stroke. Restorative strategies target neuroplasticity mechanisms with the aim of restoring impaired cognitive functions, while compensatory approaches focus on functional adaptation through alternative strategies and environmental modifications. Current evidence suggests that the efficacy of each approach varies based on multiple factors including time post-stroke, severity of impairment, specific cognitive domains affected, and individual patient characteristics.

The most effective clinical applications may involve strategic integration of both approaches, leveraging their complementary strengths. Restorative methods may be prioritized in early recovery phases with milder impairments, while compensatory strategies may be particularly valuable for chronic deficits and more severe impairments. Future research should address existing methodological limitations, identify predictors of treatment response, and develop personalized rehabilitation algorithms to optimize functional outcomes for stroke survivors.

Stroke remains a leading cause of long-term disability worldwide, with cognitive impairment representing a common and devastating consequence that profoundly affects patients' quality of life and functional independence [31]. Understanding the specific stroke characteristics that influence cognitive outcomes is crucial for developing targeted rehabilitation strategies and improving prognostic accuracy. This review systematically examines the impact of three fundamental stroke characteristics—lesion location, brain network disruption, and vascular pathophysiology—on cognitive outcomes, framed within the context of comparative cognitive rehabilitation research.

The connection between stroke and cognitive impairment is well-established, affecting approximately 30-70% of stroke survivors [31]. The heterogeneity of cognitive deficits observed following stroke reflects the complex interplay between focal injury, distributed network disruption, and underlying vascular pathology. Recent advances in neuroimaging and network neuroscience have begun to unravel the mechanisms by which these factors collectively contribute to cognitive outcomes, providing a more nuanced understanding that moves beyond simple lesion-volume approaches.

This analysis synthesizes current evidence regarding how specific stroke features predict cognitive performance, with particular emphasis on implications for comparative rehabilitation science. By examining the structural and functional network consequences of stroke through a comparative lens, we aim to inform the development of more precisely targeted cognitive rehabilitation interventions based on individual stroke characteristics.

Stroke Lesion Location and Cognitive Outcome

The Independent Predictive Value of Lesion Location

Stroke location has emerged as a powerful independent predictor of cognitive outcome, providing prognostic value beyond traditional measures such as stroke volume and initial clinical severity [32]. A prospective study of 428 patients with ischemic stroke demonstrated that lesion location remained the strongest independent predictor of performance on the Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA) at 3 months post-stroke, significantly improving prediction models that included only age, initial National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale score, and stroke volume [32]. The area under the curve for predicting cognitive outcome increased from 0.697 to 0.771 when lesion location was added to the model, highlighting its substantial contribution to prognostic accuracy [32].

The brain demonstrates a remarkable degree of functional specialization, with specific cognitive domains predominantly mediated by distinct neuroanatomical regions. Consequently, the location of a stroke lesion directly determines the pattern of cognitive deficits observed [31]. For instance, strokes affecting the frontal lobes are frequently associated with executive dysfunction, including impairments in planning, problem-solving, and cognitive flexibility [31]. In contrast, lesions involving the temporal lobes often lead to memory impairment, particularly when hippocampal structures or their connections are compromised [31]. This regional specificity explains why two strokes of similar volume can produce dramatically different cognitive profiles depending on their anatomical coordinates.

Eloquent Cognitive Regions Identified Through Advanced Neuroimaging

Advanced neuroimaging techniques have enabled researchers to identify particularly "eloquent" regions for cognitive function that, when damaged, disproportionately impact cognitive outcomes. Using voxel-based lesion-symptom mapping in a development sample of 215 patients, researchers created statistical maps that identified critical regions where lesions consistently predicted poor cognitive performance [32]. When validated in an independent replication sample, these maps confirmed that lesions in hub regions—particularly those involved in large-scale brain networks such as the default mode network and frontoparietal control network—were most detrimental to cognitive recovery [32].

Table 1: Impact of Specific Lesion Locations on Cognitive Domains

| Lesion Location | Primary Cognitive Domains Affected | Characteristic Deficits |

|---|---|---|

| Frontal Lobes | Executive Function, Attention | Impaired planning, reduced mental flexibility, poor problem-solving, diminished attentional control |

| Temporal Lobes | Memory, Language | Verbal and visual memory deficits, anomia, impaired comprehension |

| Parietal Lobes | Visuospatial Processing, Attention | Neglect, constructional apraxia, impaired mental rotation |

| Subcortical Structures | Executive Function, Processing Speed | Mental slowing, impaired set-shifting, reduced working memory capacity |

| White Matter Tracts | Processing Speed, Executive Function | Disconnection syndromes, slowed information processing, impaired interhemispheric integration |

Experimental Protocol for Lesion Location Analysis

The methodology for establishing lesion location as an independent predictor of cognitive outcome typically involves:

- Patient Recruitment: Consecutive patients with confirmed ischemic stroke are recruited prospectively, with imaging performed within 24-72 hours of symptom onset [32].

- Image Acquisition: High-resolution structural MRI (including T1, T2, FLAIR, and DWI sequences) is obtained using standardized protocols [32].

- Lesion Mapping: Individual stroke lesions are manually delineated on diffusion-weighted imaging or T2-weighted sequences and normalized to a standard brain template [32].

- Cognitive Assessment: Standardized cognitive assessment using instruments such as the Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA) is performed at predetermined time points (e.g., 3 months post-stroke) [32].

- Statistical Analysis: Voxel-based lesion-symptom mapping correlates lesion location with cognitive scores, while multivariate regression models assess the independent contribution of lesion location after controlling for covariates such as age, stroke volume, and initial severity [32].

Brain Network Disruption and Cognitive Impairment

Structural and Functional Network Disruption in Vascular Cognitive Impairment

The traditional focal lesion model of stroke has been substantially augmented by understanding strokes as disconnection syndromes that disrupt distributed brain networks [33] [34]. Research on vascular cognitive impairment (VCI) reveals that cerebral small vessel disease causes significant disruptions in structural brain networks, characterized by reduced white matter integrity and altered network topology [33]. Diffusion tensor imaging (DTI) studies consistently show that individuals with VCI exhibit reduced fractional anisotropy (indicating white matter damage) and increased mean and radial diffusivity compared to healthy controls [33].

At the network level, structural analyses demonstrate lower global and local efficiency, reduced small-world properties, and increased characteristic path length in VCI patients [33]. These topological changes reflect a less optimized network architecture that impairs efficient information transfer between brain regions. Notably, these disruptions are particularly evident in key regions of the default mode network and visual networks, suggesting selective vulnerability of these systems to vascular pathology [33].

Structure-Function Coupling as a Compensatory Mechanism

A paradoxical finding in VCI research is that despite significant structural network disruption, functional network topology often remains relatively preserved [33]. This apparent discrepancy may be explained by enhanced structure-function coupling observed in critical nodes of the default mode and visual networks in VCI participants [33]. This enhanced coupling correlates with better performance in memory function and information processing speed, particularly in regions such as the temporal calcarine, insula, occipital, and lingual areas [33].

This phenomenon may represent a compensatory mechanism in which the brain maximizes the functional utility of remaining structural connections to maintain cognitive performance despite accumulating pathology. The enhancement of structure-function coupling in early disease stages contrasts with the breakdown of such coupling in more advanced neurodegenerative conditions, suggesting a potential window for therapeutic intervention when compensatory plasticity remains robust.

Rich-Club Organization and Cognitive Vulnerability

The brain's rich-club organization—a hierarchy in which highly connected hub regions are densely interconnected with each other—appears particularly vulnerable to vascular pathology [34]. Research comparing preclinical cognitive impairment (PCI) and mild cognitive impairment (MCI) in cerebral small vessel disease demonstrates that while rich-club organization remains relatively intact in PCI, it becomes significantly disrupted in MCI patients [34].

Nodal strength loss predominantly affects hub nodes rather than peripheral nodes in MCI patients, with significant disruption observed in rich-club connections that link these central hubs [34]. This pattern of disruption has profound implications for cognitive function, as rich-club connections facilitate efficient integration of information across distributed brain networks. The association between white matter hyperintensities and executive function is mediated specifically by microstructural changes in these central network connections, highlighting their critical role in maintaining cognitive performance [34].

Table 2: Brain Network Metrics and Their Cognitive Correlates in Cerebrovascular Disease

| Network Metric | Description | Alteration in VCI | Cognitive Correlation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Global Efficiency | Measure of overall network integration | Decreased | Associated with processing speed and executive function |

| Local Efficiency | Measure of local information transfer | Decreased | Correlates with memory and attention |

| Characteristic Path Length | Average shortest path between nodes | Increased | Inversely related to processing speed |

| Small-Worldness | Balance between segregation and integration | Reduced | Associated with multiple cognitive domains |

| Rich-Club Organization | Interconnectivity of hub regions | Disrupted in MCI | Predicts executive function and global cognition |

| Structure-Function Coupling | Alignment between structural and functional connectivity | Enhanced in early VCI | Correlates with memory and processing speed |

Experimental Protocol for Network Analysis

The standard methodology for investigating brain network disruption in cerebrovascular disease includes:

- Participant Selection: Recruitment of carefully characterized patients with cerebral small vessel disease across the cognitive spectrum (preclinical, mild cognitive impairment) alongside matched healthy controls [33] [34].

- Multimodal Imaging: Acquisition of high-resolution structural MRI, diffusion tensor imaging, and resting-state functional MRI using standardized protocols on 3.0 Tesla scanners [33].

- Network Construction: Structural networks are reconstructed from DTI data using deterministic or probabilistic tractography, while functional networks are derived from resting-state fMRI correlation matrices [33] [34].

- Graph Theory Analysis: Calculation of global and nodal graph metrics including efficiency, path length, small-worldness, and rich-club coefficients [34].

- Structure-Function Coupling Assessment: Quantification of the relationship between structural connectivity strength and functional connectivity magnitude for each region pair [33].