Bregma and Lambda: Mastering Skull Landmarks for Precision Rodent Stereotaxic Surgery

This article provides a comprehensive guide to the critical skull landmarks, bregma and lambda, in rodent stereotaxic surgery.

Bregma and Lambda: Mastering Skull Landmarks for Precision Rodent Stereotaxic Surgery

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide to the critical skull landmarks, bregma and lambda, in rodent stereotaxic surgery. Tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it covers the foundational neuroanatomy of these landmarks, detailed methodological protocols for their use in surgical targeting, strategies for troubleshooting common errors and optimizing accuracy, and a validation of techniques through comparison with modern digital atlases. The content synthesizes current research and best practices to empower scientists in achieving highly reproducible and precise intracranial interventions, thereby enhancing experimental validity and supporting the principles of the 3Rs (Replacement, Reduction, and Refinement) in animal research.

The Neuroanatomical Basis: Defining Bregma, Lambda, and the Stereotaxic Coordinate System

The advent of the stereotaxic apparatus by Victor Horsley and Robert Clarke in 1906 revolutionized neuroscience research by enabling precise three-dimensional navigation within the brain [1]. This foundational technology, based on a Cartesian coordinate system, allows researchers to target specific brain structures with remarkable accuracy. In rodent models, this technique relies critically on external skull landmarks, particularly the bregma and lambda points, to define the coordinate system origin and alignment [1] [2]. Despite its widespread adoption, challenges persist in consistently identifying these landmarks, with recent studies revealing significant discrepancies that can impact surgical outcomes [1] [2]. This technical guide explores the principles, applications, and refinements of stereotaxic technology, with emphasis on proper bregma and lambda identification to enhance precision in rodent neurosurgery.

Historical Development and Fundamental Principles

Origins of Stereotaxic Technology

The conceptual foundation for stereotaxic surgery emerged in 1889 when Professor Dmitry Nikolaevich Zernov introduced the "encephalometer," which used a geographical map concept around the head with an equator and meridian for spatial navigation [1]. However, the first stereotaxic apparatus in its modern form was developed by Victor Horsley (a neurosurgeon) and Robert Clarke (a physiologist) in 1906 [1] [3]. Their collaborative work produced an apparatus that allowed precise navigation along three axes in the monkey skull based on the Cartesian coordinate system [1]. This groundbreaking invention ignited the field of stereotactic neurosurgery, which Spiegel and Wycis later adapted for human procedures in 1947 [3].

The Cartesian Coordinate System in Stereotaxic Navigation

The Horsley-Clarke apparatus implements a 3D Cartesian system with three fundamental axes [1]:

- Mediolateral (ML) axis: x-axis representing left-right movement

- Anteroposterior (AP) axis: y-axis representing front-back movement

- Dorsoventral (DV) axis: z-axis representing up-down movement

This coordinate system enables researchers to define any point within the brain using three numerical coordinates relative to a defined origin point [3]. The mathematical foundation relies on affine conversions between coordinate systems using matrices that specify rotation, scaling, and translation parameters [3]. The relationship between different coordinate spaces (anatomical, frame-based, and head-stage) follows the transformation formula: T = R × S × P + t, where R is rotation, S is scaling, P is the original coordinate, and t is translation [3].

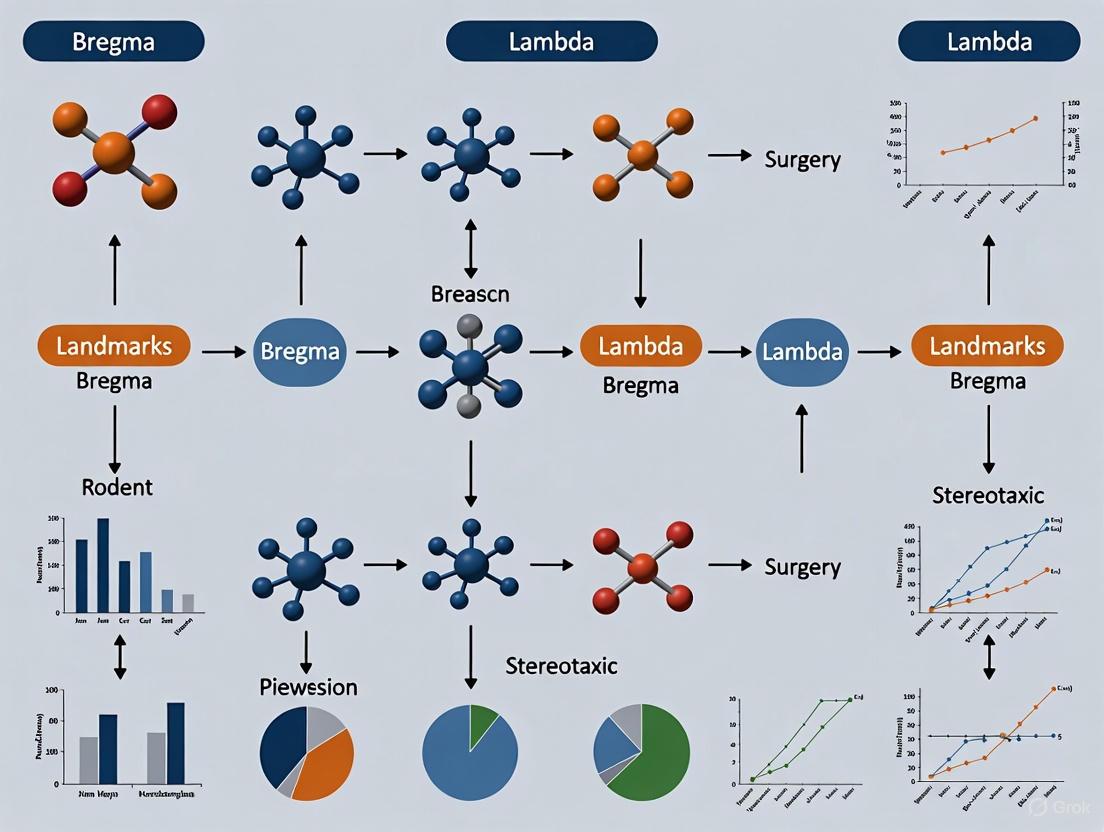

Figure 1: Stereotaxic Navigation Workflow. The process begins with identification of skull landmarks (bregma and lambda) to establish a 3D coordinate system, which is then translated through mathematical transformations into frame-based navigation parameters to reach target brain structures, often with reference to stereotaxic atlases.

Rodent Skull Landmarks: Bregma and Lambda

Anatomical Definitions and Significance

In rodent stereotaxic surgery, the skull provides the critical reference points for establishing coordinate systems. The adult mouse skull comprises 26 bones and joints connected by sutures [1]. Three key sutures are visible from a dorsal view:

- Coronal suture: A parabolic curve between the frontal and parietal bones

- Sagittal suture: Divides the skull into two halves along the medial line

- Lambdoidal suture: Resembles the Greek letter lambda at the posterior skull

The bregma point is defined as the intersection of the coronal and sagittal sutures, while the lambda occurs at the intersection of the sagittal and lambdoidal sutures [1]. The bregma serves as the most common origin point (0,0,0) for the stereotaxic coordinate system in rodents, while lambda is essential for aligning the dorsoventral coordinates and ensuring proper head leveling [1] [4].

Technical Challenges in Landmark Identification

A significant challenge in stereotaxic surgery is the accurate and consistent identification of the bregma point. The renowned Paxinos and Franklin brain atlases, while widely used, lack explicit instructions for bregma determination [1]. Compounding this problem, many researchers incorrectly assume the bregma is simply the crossing point of the coronal and sagittal sutures. However, Paxinos and Watson specifically define bregma as the "midpoint of the curve of best fit along the coronal suture" – a mathematically ambiguous definition that contributes to variability in identification [2].

Recent studies have revealed concerning discrepancies in skull and brain landmark measurements. Research comparing different identification methods found that in 44% of animals (11 out of 25), the traditional approach to locating bregma differed from a more precise mathematical method by ≥0.2 mm [2]. This variation exceeds the size of many rodent brain nuclei and subregions, potentially compromising experimental outcomes.

Enhanced Bregma Localization Methodology

To address these challenges, a novel computer-assisted method for bregma identification has been developed [2]:

- Digital Imaging: Capture a high-resolution digital picture of the exposed skull cap

- Mathematical Fitting: Mathematically fit a curve to the outline of the coronal suture

- Midline Determination: Delineate the brain midline based on the temporal ridges of the skull

- Point Calculation: Define the bregma as the intersection point of these two lines

This refined approach significantly decreases stereotaxic error compared to traditional visual estimation methods [2]. Implementation of this technique requires:

- Digital camera or microscope with imaging capabilities

- Image processing software capable of curve fitting

- Understanding of basic skull anatomy for landmark verification

Table 1: Comparison of Bregma Identification Methods

| Method | Technique | Precision | Error Rate | Advantages |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional Visual | Visual estimation of suture intersection | >0.2 mm in 44% of cases | High | Fast, requires no special equipment |

| Mathematical Fitting | Computer-assisted curve fitting to coronal suture | Significantly improved | Reduced by >50% | Objective, reproducible, higher accuracy |

| Paxinos Definition | Midpoint of curve of best fit along coronal suture | Variable interpretation | Moderate | Standardized reference |

Stereotaxic Apparatus and Instrumentation

Evolution of Stereotaxic Equipment

Modern stereotaxic instruments for rodents have evolved significantly from the original Horsley-Clarke design while maintaining the same fundamental principles. Contemporary systems typically include:

- A horizontal base plate

- One or two micromanipulators affixed to the frame

- Specialized holders for electrodes, syringes, or cannulas

- Species-specific ear bars and head holders for stabilization [1]

Several companies manufacture stereotaxic equipment, including Kopf Instruments, RWD Life Science, Harvard Apparatus, World Precision Instruments, and Stoelting Company [1]. Recent technological advances have introduced digital displays, motorized controls, and even integrated warming systems to maintain rodent body temperature during surgical procedures [5] [6].

Technical Specifications of Modern Systems

Contemporary stereotaxic instruments offer varying levels of precision to accommodate different research needs:

Table 2: Comparison of Modern Stereotaxic Instrument Specifications

| Manufacturer | Model Type | Precision Range | Key Features | Animal Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| World Precision Instruments | Ultra Precise Digital | 1 micron (0.001 mm) | Digital LED display, integrated warming base, dual manipulator capability | Mice and small rodents (10-75g) |

| Stoelting Co. | Just for Mouse Series | 1-100 microns | Warmer-ready base, gas anesthesia compatible, small footprint (25×25cm) | Transgenic and knock-out mice |

| RWD Life Science | Automated Stereotaxic Instrument | 1 μm | Integrated brain atlas software, anti-collision function, automatic procedures | Mice, rats, and large animals |

| RWD Life Science | Digital Stereotaxic | 10 μm | Digital display module, displacement sensor, arbitrary origin setting | Rats and mice |

Modern innovations include 3D-printed headers that integrate multiple functions, significantly reducing surgical time. One study demonstrated that such modifications decreased total operation time by 21.7%, primarily by streamlining the bregma-lambda measurement process [7].

Experimental Protocols and Methodological Considerations

Standard Stereotaxic Surgical Procedure

A refined stereotaxic surgery protocol for rodents incorporates technical improvements that enhance survival and precision [4]:

Pre-surgical Preparation

- Pre-warm the heating pad to maintain body temperature (37.5-38.5°C)

- Administer anesthesia (e.g., ketamine/dexmedetomidine mixture)

- Shave the head area from ears to between the eyes

- Apply eye cream to prevent corneal dehydration

- Ensure adequate blood oxygenation (>90%) throughout procedure

Head Positioning and Landmark Identification

- Place the animal in the stereotaxic apparatus with equal ear bar readings on both sides

- Clean the skull surface and expose bregma and lambda

- Level the head by ensuring identical dorsoventral coordinates at bregma and lambda (difference <0.3 mm) [4]

- Record the anteroposterior and lateral coordinates at bregma

Coordinate Calculation and Targeting

- Calculate target coordinates relative to bregma using a stereotaxic atlas

- Mark the cannula locations on the skull

- Drill burr holes at calculated coordinates

- Gently puncture the meninges to allow unobstructed cannula insertion

Surgical Implementation and Recovery

- Lower the cannula or electrode carefully to the final ventral coordinate

- Apply dental cement to fix the implant in place

- Administer warm sterile saline (~10 ml/kg, subcutaneously) for rehydration

- Monitor the animal closely during recovery, maintaining thermal support

Impact of Technical Refinements on Surgical Outcomes

Implementation of refined techniques significantly improves surgical outcomes. Studies demonstrate that modified protocols incorporating active warming systems and improved landmark identification reduce non-survival rates and minimize postoperative weight loss [4] [7]. Specifically, the use of active warming pads to prevent hypothermia (a common complication of isoflurane anesthesia) increased survival rates from 0% to 75% in one severe TBI model study [7].

Furthermore, the implementation of continuous monitoring of blood oxygenation, heart rate, and body temperature throughout the procedure has been shown to significantly enhance postoperative recovery and reduce complications [4].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Equipment and Reagents

Table 3: Essential Materials for Rodent Stereotaxic Surgery

| Item | Function | Technical Specifications | Example Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Stereotaxic Frame | Precise 3D navigation | Precision: 1-100 μm, Weight capacity: 10-75g (mice) | All stereotaxic procedures |

| Digital Coordinate Display | Accurate coordinate reading | Resolution: 1 μm, LED display for low-light conditions | High-precision targeting |

| Active Warming System | Maintain body temperature | PID controlled, target temperature: 37.5-38.5°C | Prolonged surgeries, prevention of hypothermia |

| Gas Anesthesia System | Maintain surgical anesthesia | Isoflurane with oxygen mixture (30-35% O₂) | All survival surgeries |

| Rodent Stereotaxic Atlas | Target coordinate reference | Paxinos & Franklin, Allen Brain Atlas | Coordinate determination |

| Microdrill | Create burr holes in skull | 0.5-1.0 mm drill bits, precise depth control | Access to brain structures |

| Dental Cement | Secure implants to skull | Fast-setting, biocompatible | Chronic implant fixation |

| Skull Screws | Anchor dental cement | 0.5-1.0 mm diameter, stainless steel | Chronic implant stability |

| Analgesics | Post-operative pain management | Carprofen (4.0-5.0 mg/kg) | Animal welfare compliance |

The Horsley-Clarke stereotaxic apparatus represents a foundational technology in neuroscience research, enabling unprecedented precision in accessing specific brain regions. The proper identification of bregma and lambda landmarks remains crucial for accurate targeting, with recent methodological refinements significantly improving precision through mathematical approaches to landmark identification. Contemporary technological advances, including digital displays, active warming systems, and computer-assisted planning, have further enhanced the capabilities of stereotaxic systems while improving animal welfare outcomes. As stereotaxic techniques continue to evolve, maintaining focus on accurate landmark identification and implementation of refined surgical protocols will ensure the continued utility of this powerful methodology in advancing our understanding of brain function and pathology.

The bregma is a fundamental cranial landmark defined as the point on the superior aspect of the skull where the coronal suture intersects perpendicularly with the sagittal suture [8] [9]. This anatomical junction marks the convergence of three skull bones: the frontal bone anteriorly and the two parietal bones posteriorly and laterally [8]. The term itself is derived from the Ancient Greek word brégma, meaning "the bone directly above the brain" [8]. In neonatal and infant anatomy, this location corresponds to the site of the anterior fontanelle, a membranous, unossified area that allows for skull flexibility during birth and rapid brain growth postnatally [8] [9]. This fontanelle typically closes between 18 and 36 months of life as the surrounding bones fuse, forming the definitive bregma point seen in adulthood [8]. Its consistent and identifiable nature makes it an indispensable reference point across multiple disciplines, including clinical neurology, neurosurgery, anthropology, and particularly in preclinical neuroscience research using rodent models.

Bregma in Rodent Stereotaxic Surgery

In experimental neuroscience, the bregma is the cornerstone of the stereotaxic coordinate system for targeting specific brain regions in rodent models. The stereotaxic apparatus operates on a three-dimensional Cartesian coordinate system, where the bregma most commonly serves as the origin point (0,0,0) for the anteroposterior (AP), mediolateral (ML), and dorsoventral (DV) axes [1] [10]. To establish a level skull position—a critical prerequisite for accurate coordinate translation—the lambda (the junction of the sagittal and lambdoid sutures) is aligned to the same dorsoventral height as the bregma [11]. This "flat-skull position" ensures that the horizontal plane is consistent with the reference planes used in stereotaxic brain atlases [11].

Despite its widespread adoption, used in 96% of stereotaxic surgery publications, targeting accuracy can be variable [10]. A critical review of practice reveals that while bregma is the optimal origin for rostral brain targets, for 27% of targets the skull entry point was closer to lambda, and for 38% the target itself was closer to the interaural line midpoint [10]. This indicates that the choice of the closest surgical landmark to the target can, in theory, improve precision. The accuracy of bregma-referenced targeting is influenced by several factors, including inter-animal anatomical variability, the skill of the operator in identifying the suture intersection, and the strain, sex, and age of the animal, which can cause significant deviations from the standard atlas brain [1] [10].

Table 1: Prevalence of Bregma as a Stereotaxic Origin in Rat Surgery (Analysis of 235 studies)

| Stereotaxic Origin | Prevalence in Studies | Closest to Target | Remarks |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bregma | 96% | 58% of targets | Optimal for rostral brain structures [10]. |

| Interaural Line Midpoint (IALM) | ~2% | 38% of targets | Yields shorter Euclidean distance for caudal targets [10]. |

| Lambda | ~1% | 5% of targets | Closer entry point for 27% of targets [10]. |

Quantitative Data on Targeting Accuracy and Challenges

Quantitative assessments of stereotaxic surgery outcomes highlight significant challenges in achieving consistent targeting. A systematic review of rat stereotaxic procedures found that in 39% of studies, no verification of implantation accuracy was performed at all, and only 8% of studies explicitly reported the number of on-target implants [10]. This reporting gap makes it difficult to assess the true efficacy and reproducibility of the technique across laboratories.

More objective, image-based analyses confirm these variability concerns. One study utilizing post-operative CT and MRI to reconstruct surgical trajectories found that only about 30% of electrodes were located within the targeted subnucleus structure, despite identical entry and target coordinates being used for all animals [12]. This inaccuracy can be attributed to multiple sources of error, including inter-individual anatomical differences, errors in establishing the flat-skull position, and crucially, inconsistencies in the precise identification of the bregma point itself [1] [12]. These discrepancies are not merely statistical; they have a direct impact on experimental outcomes, potentially leading to false negative results or misinterpretation of data due to off-target interventions. Furthermore, the conventional method of verification using 2D histology is susceptible to manual alignment errors, tissue distortion, and provides an incomplete picture of the full 3D trajectory [12].

Table 2: Sources of Error in Bregma-Referenced Stereotaxic Surgery

| Category of Error | Specific Examples | Impact on Accuracy |

|---|---|---|

| Anatomical & Biological | Inter-strain and inter-individual brain variability [10]; Age and sex differences [10]; Divergence from atlas reference brain [1] | Mismatch between atlas coordinates and actual brain structure location. |

| Surgical Procedure | Inaccurate identification of bregma and lambda [1]; Failure to achieve a true flat-skull position [11]; Incorrect calibration of stereotaxic apparatus | Systematic offset in all three coordinate axes (AP, ML, DV). |

| Verification & Reporting | Lack of post-operative verification [10]; Use of low-resolution 2D histology [12]; Failure to report off-target rates [10] | Inability to identify and exclude inaccurate data, perpetuating poor practice. |

Advanced Protocols and Methodological Refinements

Standard Protocol for Bregma Localization and Skull Alignment

A detailed protocol for establishing a reliable stereotaxic coordinate system is as follows:

- Anesthesia and Fixation: The rodent (rat or mouse) is anesthetized and securely placed in the stereotaxic frame using ear bars. The head is stabilized, and an incision is made to expose the skull surface.

- Skull Preparation and Suture Visualization: The periosteum and any connective tissue are gently cleared from the surface of the skull. To enhance the visibility of the cranial sutures, a cotton-tipped applicator with a small amount of hydrogen peroxide (H₂O₂) can be applied briefly to the skull, making the coronal and sagittal sutures more distinct [11].

- Identifying Bregma and Lambda: Using a stereotaxic microscope, the surgeon identifies the coronal suture, which runs transversely between the frontal and parietal bones, and the sagittal suture, which runs longitudinally along the midline between the parietal bones. Their intersection is the bregma [8] [1]. The lambda is identified posteriorly as the intersection of the sagittal suture with the lambdoid suture [1].

- Achieving Flat-Skull Position: The stereotaxic arm is used to position the tip of a fine needle or probe precisely on the bregma point, and the dorsoventral (DV) coordinate is recorded. The needle is then moved to the lambda point, and the DV coordinate is checked. The head position is adjusted (typically by tilting the nose clamp) until the DV readings for bregma and lambda are identical, confirming the skull is level in the anteroposterior plane [11]. This establishes the horizontal plane.

Image-Guided and Multi-Modal Verification

To address the limitations of traditional methods, advanced protocols using multi-modal imaging have been developed for retrospective assessment of targeting accuracy [12]. The workflow for this approach is as follows:

- Post-operative Imaging: After surgery, the animal is scanned using both in vivo Micro-CT (to visualize the physical implant or a radio-opaque marker) and in vivo MRI (to visualize the trace left by the electrode or needle in the brain tissue and to assess potential hemorrhage or damage).

- Image Co-registration and 3D Reconstruction: The post-operative CT and MRI images are fused together and then co-registered to a standard 3D reference brain atlas, such as the Allen Mouse Brain Common Coordinate Framework (CCFv3) [13] or other high-resolution atlases [14].

- Trajectory Reconstruction and Accuracy Quantification: The surgical trajectory is reconstructed in 3D from the imaging data. The Euclidean distance between the actual tip location and the intended target coordinate is calculated, providing an objective, quantitative measure of Target Localization Error [12].

- Benefit: This method allows for the early exclusion of off-target subjects in longitudinal studies, saving time and resources, and provides a more comprehensive and objective assessment of surgical outcome than 2D histology [12].

Diagram 1: Bregma-based stereotaxic surgery and verification workflow.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions for Rodent Stereotaxic Surgery

| Item | Function / Application | Key Details |

|---|---|---|

| Stereotaxic Apparatus | Precise 3D navigation and head fixation. | Includes base plate, micromanipulators, ear bars, and a nose/incisor clamp [1]. |

| Stereotaxic Brain Atlas | Provides coordinate maps of brain structures. | e.g., Paxinos & Franklin's "The Mouse Brain in Stereotaxic Coordinates"; Paxinos & Watson's "The Rat Brain..." [1]. |

| Digital Stereotaxic Ruler | Enhances precision of coordinate measurement. | Reduces parallax error compared to manual vernier scales [10]. |

| Hydrogen Peroxide (H₂O₂) | Chemical aid for visualizing skull sutures. | Blunt scraping and application of H₂O₂ makes suture intersections (bregma/lambda) clearer [8] [11]. |

| High-Resolution 3D Reference Atlases | For advanced planning and verification. | e.g., Allen CCFv3 [13], STAM (1-μm resolution) [14]; used for co-registration with post-op images. |

| Multi-Modal Imaging (MRI/CT) | In vivo assessment of targeting accuracy. | Post-operative MRI shows electrode trace/lesion; CT visualizes physical implant; combined for 3D trajectory reconstruction [12]. |

The definition of bregma as the intersection of the sagittal and coronal sutures remains a bedrock principle in rodent stereotaxic surgery. However, the field is moving toward a more nuanced and sophisticated application of this landmark. Future directions focus on mitigating the documented variability in targeting accuracy. This includes the development of more comprehensive and high-resolution 3D digital atlases, such as the STAM atlas with its isotropic 1-μm resolution, which allows for arbitrary-angle slice generation and vastly improved structure delineation [14]. There is also a growing emphasis on the adoption of objective, image-based verification protocols to replace or supplement traditional histology [12]. Furthermore, the creation of standardized, population-averaged atlas templates across different developmental stages, as seen in the Developmental Mouse Brain Common Coordinate Framework (DevCCF), provides a more robust anatomical context for integrating data from diverse studies [13].

In conclusion, while bregma's anatomical definition is constant, its effective use in research requires a critical understanding of its limitations and the integration of modern techniques. By adhering to refined surgical protocols, employing the closest appropriate cranial landmark to the target, and utilizing advanced tools for planning and verification, researchers can significantly enhance the precision, reproducibility, and reliability of stereotaxic interventions in rodent models. This rigorous approach ensures that the foundational role of bregma in neuroscience research continues to be supported by evolving best practices.

In rodent stereotaxic surgery, a cornerstone of neuroscience and drug development research, precise navigation within the brain is paramount. This whitepaper defines the lambda, the cranial landmark formed by the intersection of the sagittal and lambdoid sutures, and details its critical role as a reference point in experimental protocols [15] [1]. While essential for aligning the skull in the stereotaxic apparatus, empirical data reveals significant variability in the spatial position of lambda relative to underlying brain anatomy, challenging its reliability as a sole fiducial marker [16] [17]. This guide provides an in-depth technical overview of lambda's anatomy, quantifies its limitations, outlines modern methodologies for its identification, and presents essential tools for researchers to enhance the accuracy and reproducibility of intracranial interventions.

Anatomical Definition and Landmark Context

The lambda is a defined craniometric point on the dorsal surface of the skull. It is located at the junction where the sagittal suture and the lambdoid suture meet [15] [18].

- Sagittal Suture: This is the fibrous joint that runs along the midline of the skull, connecting the left and right parietal bones [18] [19].

- Lambdoid Suture: This is the fibrous joint that separates the parietal bones from the occipital bone posteriorly. Its name is derived from its resemblance to the Greek letter lambda (λ) [15] [20].

The point where these two sutures converge is named after the same Greek letter [15]. In a developmental context, the lambda corresponds to the site of the posterior fontanelle in the fetal skull, a membranous area that later ossifies [15].

The lambda's anatomical counterpart in the stereotaxic system is the bregma, located anteriorly at the intersection of the sagittal suture and the coronal suture [1] [21]. Together, bregma and lambda serve as the two most critical external landmarks for establishing the stereotaxic coordinate system in rodents. The line connecting them defines the anteroposterior axis, and ensuring this line is level (i.e., both points are at the same dorsoventral coordinate) is a fundamental step before any surgical intervention [1] [21].

Table: Key Cranial Sutures and Landmarks in Rodent Stereotaxic Surgery

| Anatomical Feature | Description | Role in Stereotaxic Surgery |

|---|---|---|

| Lambda | Junction of the sagittal and lambdoid sutures [15] | Posterior reference point for aligning the skull in the stereotaxic apparatus [1] |

| Bregma | Junction of the sagittal and coronal sutures [1] | Anterior reference point; most common origin (zero point) for stereotaxic coordinates [1] |

| Sagittal Suture | Midline suture between the two parietal bones [18] | Defines the medial-lateral midline of the skull |

| Lambdoid Suture | Inverted V-shaped suture between parietals and occipital bone [15] [20] | Forms the posterior boundary for defining the skull-flat position |

| Coronal Suture | Suture between the frontal and parietal bones [1] | Forms the anterior boundary for defining the skull-flat position |

Lambda in Rodent Stereotaxic Research: Applications and Limitations

The stereotaxic apparatus, based on a 3D Cartesian coordinate system, allows for precise navigation along the mediolateral (x), anteroposterior (y), and dorsoventral (z) axes [1]. In this system, the lambda is indispensable for the initial skull-leveling procedure [21]. The established protocol involves measuring the dorsoventral coordinate at both bregma and lambda; the skull is considered level ("skull-flat position") when the difference between these two measurements is less than 0.1 mm [21] [22]. This ensures the skull is positioned in a standardized plane, a critical prerequisite for accurately targeting coordinates from a stereotaxic atlas.

However, a growing body of evidence highlights a significant limitation of lambda (and bregma) as fiducial markers. A key study coregistering 3D µCT skull datasets with brain MRI from five mice found that the positions of these skull landmarks vary considerably with respect to the underlying brain anatomy [16]. The study reported a maximum distance of 1.68 mm between the z-positions (dorsoventral) of lambda across different subjects, concluding that these two landmarks cannot be accepted as reliable fiducials for direct registration to a standard brain space like Waxholm Space (WHS) [16]. This inter-animal variability can be attributed to factors such as strain, sex, age, and body weight [1] [17].

Consequently, while lambda remains essential for mechanical alignment of the skull, the most accurate stereotaxic surgery for caudal brain structures is achieved when bregma is used as the reference for rostral structures and the interaural line is used for caudal structures, especially when animals of different weights are employed [17].

Table: Quantitative Variability of Skull Landmarks (Based on Coregistered µCT/MRI Data)

| Landmark | Nature of Variability | Reported Extent of Variation | Functional Impact |

|---|---|---|---|

| Lambda | Dorsoventral (z-position) variation between subjects [16] | Up to 1.68 mm [16] | Challenging for direct and accurate registration to standard brain atlases [16] |

| Bregma | Dorsoventral (z-position) variation between subjects [16] | Up to 1.2 mm [16] | Reduces reliability as a sole fiducial point for precise coordinate calculation [16] |

Advanced Detection and Validation Methodologies

Automated Detection via Deep Learning

To mitigate human error and improve repeatability, an automated framework using deep learning has been developed to locate bregma and lambda in rodent skull images [23]. This method addresses the challenge that, despite being theoretically easy to find, individual anatomical variations and obscured views make these points difficult to locate consistently in practice [23].

The framework employs a two-stage process:

- Skull Region Detection: A Region-Based Convolutional Neural Network (Faster R-CNN) is used to first detect the skull region of interest (ROI) in a raw input image, saving computing resources and focusing the subsequent analysis [23].

- Landmark Segmentation: A Fully Convolutional Network (FCN), modified with residual networks and batch normalization, then segments the precise locations of bregma and lambda within the skull ROI. The network is trained not with simple binary labels but with 2D Gaussian distributions centered on the true bregma and lambda points, which transforms the task into a regression problem for higher accuracy [23].

This automated system has demonstrated a mean error of less than 300 μm when compared to expert-placed landmarks and is robust to different lighting conditions and animal orientations in the images [23].

Validation of Internal Brain Landmarks

Given the variability of skull-based landmarks, research has validated a set of 16 internal brain landmarks as more reliable fiducials for registration to standard reference spaces like the Waxholm Space (WHS) [16]. These landmarks were identified to be reliably located by different individuals (both specialists and novices) across different MRI modalities and in various specimens, with a probability of being correctly found exceeding 95% [16]. The average deviations for these validated fiducials were 1.0, 0.6, and 1.5 voxels in the x, y, and z directions, respectively, demonstrating superior consistency compared to skull landmarks [16].

The Researcher's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

Table: Essential Materials for Stereotaxic Surgery based on Bregma and Lambda

| Item / Reagent | Function / Application | Experimental Context |

|---|---|---|

| Stereotaxic Apparatus (e.g., from Kopf Instruments, RWD Life Science) | Precise 3D navigation and fixation of the animal's head during surgery [1] | Fundamental hardware for all stereotaxic procedures. |

| Stereotaxic Atlas (e.g., Paxinos & Franklin's MBSC/RBSC, Allen Institute CCF 3D) | Provides 3D coordinates of brain structures relative to Bregma [1] | Used to determine target coordinates for injections, implants, or lesions. |

| Viral Vectors (e.g., AAV, Lentivirus) | Delivery of genetic material for gene expression manipulation (overexpression or knockdown via siRNA) in specific brain regions [21] | Used for optogenetics, chemogenetics, or functional gene studies. |

| Tracer Dyes | Visualization of neuronal projections and circuit connectivity [21] | Injected stereotaxically to map neural pathways. |

| Electrophysiology Probes/Electrodes | Recording of neural electrical signals in awake, behaving animals [21] | Implanted to monitor neuronal firing during behavior. |

| Microdialysis Probe | Continuous monitoring of neurotransmitters, drugs, or metabolites in the brain extracellular fluid [21] | Implanted for in vivo neurochemical sampling. |

| Deep Learning Framework (e.g., Faster R-CNN & FCN) | Automated, high-precision detection of Bregma and Lambda from skull images [23] | Used to reduce human error and improve surgical consistency. |

The Critical Role of Skull Landmarks as the Origin for Stereotaxic Coordinates

Stereotaxic surgery, a cornerstone technique in modern neuroscience and drug development, enables researchers to precisely navigate the intricate landscape of the rodent brain. This sophisticated approach relies on a three-dimensional Cartesian coordinate system—comprising mediolateral (ML), anteroposterior (AP), and dorsoventral (DV) axes—to target specific brain structures with remarkable accuracy [1]. The origin and reliability of this entire system are anchored to cranial sutures, the visible landmarks on the skull surface, with the intersection points known as bregma and lambda serving as the fundamental reference points [1] [24]. The precise identification of these landmarks is not a mere preparatory step but a critical determinant of surgical success, as even minor errors in establishing this origin point can propagate through the coordinate system, leading to significant deviations at the target site. This technical guide explores the paramount importance of skull landmarks within the context of rodent surgery research, detailing the protocols for their identification, the challenges in their consistent application, and the emerging technologies poised to enhance reproducibility in stereotaxic procedures for therapeutic development.

Fundamental Skull Landmarks in Rodent Stereotaxy

The rodent skull is composed of multiple bones that fuse at junctions called sutures. For stereotaxic surgery, two suture intersections are of paramount importance, Bregma and Lambda, serving as the anchor points for the entire coordinate system [1] [24].

Bregma is defined as the point where the sagittal suture (running mid-line along the skull, separating the two parietal bones) intersects with the coronal suture (which lies between the frontal and parietal bones) [1] [24]. In a top-down view, this forms a T-shaped junction. Bregma is the most commonly used origin point (zero point) for the anteroposterior and mediolateral coordinates in stereotaxic surgery [1].

Lambda is located posterior to bregma and is defined as the point where the sagittal suture meets the lambdoidal suture (which separates the parietal bones from the occipital bone) [1]. This junction often resembles the shape of the Greek letter lambda (λ). Lambda is primarily used to level the skull along the anteroposterior axis, ensuring the head is positioned flat in the stereotaxic apparatus [24].

Table 1: Key Skull Landmarks in Rodent Stereotaxic Surgery

| Landmark | Anatomical Definition | Primary Role in Stereotaxy |

|---|---|---|

| Bregma | Intersection of the sagittal and coronal sutures [1] [24] | Serves as the origin point (0,0) for the anteroposterior and mediolateral axes [1]. |

| Lambda | Intersection of the sagittal and lambdoidal sutures [1] [24] | Used to level the skull in the anteroposterior plane, ensuring proper alignment [24]. |

The following diagram illustrates the spatial relationship between these critical landmarks and the stereotaxic coordinate system they define.

Experimental Protocols for Landmark Identification and Skull Leveling

A rigorous and standardized protocol is essential for reliably identifying bregma and lambda and ensuring the skull is correctly positioned before any surgical intervention. The following detailed methodology, adapted from standard stereotaxic procedures, is critical for achieving this [24].

Materials and Setup

- Anesthetized Rodent: The animal is properly anesthetized and secured in a stereotaxic frame.

- Stereotaxic Apparatus: A standard stereotaxic instrument (e.g., from Kopf Instruments, RWD Life Science) equipped with ear bars and an incisor bar [1].

- Surgical Tools: Sterile scalpel, forceps, and scissors for exposing the skull.

- Probe or Needle: A fine-tipped probe attached to the stereotaxic manipulator.

- Sterile Saline: To keep the exposed skull moist during the procedure.

Step-by-Step Procedure

Scalp Incision and Skull Exposure: The scalp hair is shaved, and the skin is disinfected. A midline incision is made with a scalpel to expose the skull. The underlying connective tissue is gently separated to clearly visualize the sagittal, coronal, and lambdoidal sutures [24].

Initial Bregma Identification: Lower the probe tip to the suspected bregma point—the intersection of the sagittal and coronal sutures. Carefully note the dorsoventral (DV) coordinate at this position. This is the initial DV reading for bregma [24].

Skull Leveling - Lambda Check: Raise the probe and move it posteriorly to the lambda point (intersection of the sagittal and lambdoidal sutures). Lower the probe tip to touch lambda and record its DV coordinate [24].

Alignment Adjustment: Compare the DV readings from bregma and lambda. The skull is considered level in the anteroposterior plane if the difference between these two measurements is less than 0.1 mm. If the difference exceeds this tolerance, the incisor bar must be adjusted (raised or lowered) and the measurements repeated until the skull is level [24].

Setting the Origin: Once the skull is level, return the probe to bregma. The anteroposterior and mediolateral coordinates at this point are now set to zero, establishing the origin for all subsequent coordinate calculations for targeting brain structures [24].

Table 2: Common Commercially Available Stereotaxic Systems and Related Reagents

| Item Category | Specific Examples | Primary Function |

|---|---|---|

| Stereotaxic Apparatus | Kopf Instruments, RWD Life Science, Harvard Apparatus, Stoelting Co. [1] | Provides a rigid frame and micromanipulators for precise 3D navigation of the brain. |

| Surgical Consumables | Sterile scalpels, sutures, bone drill bits, absorbent gel foam. | Essential for performing the surgery, controlling bleeding, and closing the wound. |

| Anesthesia & Analgesia | Isoflurane (inhalant), Ketamine/Xylazine (injectable), Buprenorphine (post-op pain relief). | Ensures the animal is unconscious and pain-free during and after the procedure. |

| Viral Vectors & Tracers | AAV (for gene delivery), Lectins, Fluorescent Retrograde Tracers (e.g., Fluorogold) [24]. | Used to manipulate genes or map neural circuits by delivering agents to specific brain targets. |

Challenges and Limitations in Landmark Accuracy

Despite their foundational role, the use of skull landmarks is not without significant challenges, which can introduce variability and compromise experimental outcomes.

A primary concern is the inconsistency in how bregma is identified and measured across different laboratories. Renowned atlases like Paxinos and Franklin's "The Mouse Brain in Stereotaxic Coordinates," while indispensable, lack explicit, standardized instructions for determining the bregma point [1]. This omission can lead to subjective interpretations among researchers. Furthermore, inter-strain and intra-strain variations in craniometric parameters and brain volume due to factors like body size, weight, age, and sex can affect the relationship between the external skull landmarks and the underlying brain structures, making standardized coordinates less universally precise [1].

Compounding this issue, recent studies have revealed discrepancies when comparing measurements taken directly from the skull with those derived from brain atlases or even between different atlases themselves [1]. These inconsistencies pose a major challenge for scientists attempting to compare stereotaxic coordinates across different studies or replicate published findings. The problem is exacerbated by the nature of traditional 2D reference atlases, which are often constructed from brain sections spaced hundreds of micrometers apart. This prevents the observation of continuous structural changes and can hinder accurate three-dimensional reconstruction and boundary determination [25].

Advanced Approaches and Future Directions

To overcome the limitations of traditional landmarking, the field is evolving towards more precise and reliable methodologies.

High-Resolution and 3D Digital Atlases

A significant advancement is the creation of high-resolution, three-dimensional digital reference atlases. For example, the Stereotaxic Topographic Atlas of the Mouse Brain (STAM) was constructed using a Nissl-stained image dataset with an isotropic 1-μm resolution, allowing for visualization at a single-cell level [25]. This atlas provides the 3D topography of 916 brain structures and enables the generation of slice images at arbitrary angles, offering a far more precise tool for anatomical localization than traditional atlases with large intervals between sections [25]. Such atlases are interoperable with widely used stereotaxic atlases like Paxinos and Franklin's, supporting cross-atlas navigation and improving the accuracy of targeting small nuclei and complex fiber bundles [25].

Computational and AI-Driven Landmarking

Another promising direction is the application of artificial intelligence (AI) and deep learning to automate landmark identification. Recent research has developed models using optimized 3D U-Net networks to automatically detect craniometric landmarks on medical imaging such as spiral CT (SCT) and cone-beam CT (CBCT) scans [26]. These models have demonstrated high precision, with mean radial errors consistently below 1.3-1.4 mm, even in complex conditions involving malocclusion or metal artifacts [26]. While this technology is currently more advanced in human clinical applications, its principles showcase the potential for automating and standardizing the landmarking process in preclinical research, thereby reducing human error and subjective interpretation.

The logical workflow for integrating these advanced tools into a modern stereotaxic surgery pipeline is summarized in the following diagram.

The external skull landmarks, bregma and lambda, remain the indispensable foundation upon which the precise internal navigation of the rodent brain is built. Their correct identification and use in skull leveling are paramount for the accuracy and reproducibility of stereotaxic surgery, a technique critical to neuroscience research and pharmaceutical development. While challenges related to standardization and anatomical variability persist, the field is actively addressing these through the development of ultra-high-resolution 3D digital atlases and the exploratory application of AI-driven landmark detection. By adhering to meticulous protocols for landmark-based alignment and embracing these new technologies, researchers can significantly minimize stereotaxic errors, thereby enhancing the reliability of their data and the validity of their scientific conclusions.

In rodent stereotaxic surgery, the accurate targeting of specific brain structures is foundational to neuroscience research and drug development. This precision fundamentally relies on establishing a stable and reproducible coordinate system within the skull of the animal. The flat-skull position (FSP), achieved by leveling the bregma and lambda skull landmarks to the same vertical height, serves as this critical baseline. By defining a consistent horizontal plane, the FSP ensures that the three-dimensional coordinates derived from a brain atlas can be reliably translated to the live animal. This technical guide delves into the anatomical basis, detailed protocol, and significant impact of the flat-skull position, framing it within the broader context of using cranial landmarks for neuroscientific discovery. The renowned neuroanatomist George Paxinos, whose atlases are standard in the field, emphasized that the definition and implementation of the skull-flat position for their atlases significantly improved the reproducibility of stereotaxic procedures [22].

Anatomical Foundations: Bregma and Lambda as Cartesian Origins

The stereotaxic technique operates on a simple yet powerful principle: the spatial relationships between external skull landmarks and internal brain structures are consistent within a species and strain. This allows researchers to navigate the brain using a three-dimensional Cartesian coordinate system.

- Bregma: This is defined as the point where the coronal suture (running between the frontal and parietal bones) intersects perpendicularly with the sagittal suture (running along the midline of the skull) [8]. In practical terms for rodent stereotaxy, it is often identified as the midpoint of the curve of best fit along the coronal suture, rather than merely the visual intersection, to improve accuracy [2].

- Lambda: This is the analogous point posterior to bregma, defined as the intersection of the sagittal suture and the lambdoid suture [1] [21].

- The Coordinate System: In this system, the anteroposterior (AP) axis and mediolateral (ML) axis lie within the horizontal plane established by leveling bregma and lambda. The dorsoventral (DV) axis is then perpendicular to this plane [21]. Bregma is most frequently used as the origin (zero point) for the AP and ML coordinates, from which all target measurements are made [11].

Table 1: Key Skull Landmarks in Rodent Stereotaxic Surgery

| Landmark | Anatomical Definition | Role in Stereotaxic Coordinate System |

|---|---|---|

| Bregma | Intersection of the coronal and sagittal sutures [8]. | The most common origin point (0,0) for the anteroposterior and mediolateral axes [1] [11]. |

| Lambda | Intersection of the sagittal and lambdoid sutures [1] [21]. | Used in conjunction with bregma to define and level the horizontal plane; a secondary reference point [11]. |

| Sagittal Suture | Midline suture between the two parietal bones [1]. | Defines the mediolateral midline (ML = 0) of the skull. |

| Coronal Suture | Suture between the frontal and parietal bones [1]. | Defines the anterior landmark for the bregma point. |

The Flat-Skull Position Protocol: A Step-by-Step Methodology

The following section provides a detailed experimental protocol for achieving the flat-skull position, a critical prerequisite for any stereotaxic procedure involving intracranial injections, lesions, or device implantation.

Surgical Preparation and Landmark Identification

- Anesthesia and Positioning: After inducing anesthesia (e.g., with isoflurane), secure the rodent in the stereotaxic frame using the ear bars and incisor bar. Shave the scalp, disinfect the skin, and make a midline incision to expose the skull [21].

- Cleaning and Visualizing Sutures: Gently clean the surface of the skull with a sterile saline solution or hydrogen peroxide to remove connective tissue and clarify the suture lines. This step is crucial for accurately identifying bregma and lambda [8] [11].

- Initial Bregma Measurement: Using a stereotaxic probe or needle attached to the micromanipulator, lower the tip directly onto the bregma point. Record the dorsoventral (DV) coordinate from the Vernier scale on the manipulator. This reading represents the height of bregma [21].

The Leveling Procedure

- Lambda Measurement: Raise the probe, move it to the lambda point, and lower the tip onto lambda. Record the DV coordinate at this location [21].

- Assessing Levelness: Compare the DV readings from bregma and lambda. A skull is considered level, or in the flat-skull position, when the difference between these two measurements is less than 0.1 mm [21].

- Adjusting the Incisor Bar: If the difference exceeds 0.1 mm, adjust the height of the incisor bar—lower it if lambda is higher than bregma, or raise it if lambda is lower—and repeat the measurements at both bregma and lambda until the height difference is within the acceptable tolerance [21].

- Setting the Origin: Once the skull is level, return the probe to bregma and record the final AP and ML coordinates. These values now establish the origin (0,0) for your target coordinates as listed in the stereotaxic atlas [21].

The following workflow diagram summarizes the logical sequence and decision points in this leveling procedure.

Impact and Innovations in Precision Leveling

The rigorous implementation of the flat-skull position is not a mere formality; it is a primary determinant of surgical success. Inaccuracies at this stage propagate through the entire procedure, leading to target miss and compromised experimental integrity.

Quantifying the Cost of Error

Inconsistent or inaccurate identification of bregma is a significant source of stereotaxic error. A study dedicated to improving bregma detection found that a traditional "rough" method of visual identification differed from a more precise, computer-assisted method by ≥ 0.2 mm in 44% of animals [2]. When this error was corrected using the new method, the average total stereotaxic error in implanting a microprobe was significantly reduced [2]. This highlights that minor deviations in establishing the origin point can lead to major inaccuracies in reaching the intended target, especially given that many rodent brain nuclei and subregions are smaller than 0.5 mm [1].

Table 2: Impact of Bregma Identification Method on Stereotaxic Error

| Measurement Factor | Traditional 'Rough' Method | Precise Computer-Assisted Method |

|---|---|---|

| Bregma Identification | Visual estimation of suture intersection. | Mathematical curve-fitting to coronal suture and midline [2]. |

| Rate of Substantial Error | Differed from precise method by ≥ 0.2 mm in 44% of cases [2]. | N/A (Defined as the accurate standard). |

| Resulting Implantation Error | Higher average total stereotaxic error [2]. | Significantly decreased average total stereotaxic error [2]. |

Advanced Techniques and Tools

The field is evolving with new technologies aimed at standardizing and automating landmark identification to further enhance precision and reproducibility.

- Digital and 3D Atlases: Modern reference atlases, such as the Allen Mouse Brain Common Coordinate Framework (CCF) and the new Stereotaxic Topographic Atlas of the Mouse Brain (STAM) with isotropic 1-μm resolution, provide unprecedented detail and allow for arbitrary-angle sectioning, improving the interpretation of anatomical locations [25].

- Automated Landmark Detection: Machine learning approaches are being developed to automatically detect bregma and lambda in images of the rodent skull. One framework using a region-based convolutional network and a fully convolutional network achieved localizations with mean errors of less than 300 micrometers, demonstrating robustness to varying lighting and orientation [23].

- Surgical Workflow Innovations: Modified stereotaxic devices that integrate multiple tools (e.g., a measurement probe and an impactor) into a single header can reduce the number of instrument changes. This innovation has been shown to decrease the total operation time by 21.7%, specifically improving efficiency during the Bregma-Lambda measurement phase and reducing anesthesia time [27].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Essential Materials for Rodent Stereotaxic Surgery

| Item | Function / Explanation |

|---|---|

| Stereotaxic Frame | A rigid apparatus with ear and incisor bars to immobilize the rodent's head in a fixed position [21]. |

| Micromanipulator | Device attached to the stereotaxic frame that allows precise, micrometer-scale movement of probes or injectors in 3D space [21]. |

| Stereotaxic Atlas | A reference (e.g., Paxinos and Franklin's Mouse Brain atlas) providing 3D coordinates of brain structures relative to skull landmarks [1] [22]. |

| Hamilton Syringe / Microinjector | For delivering precise, small-volume injections of viruses, tracers, or pharmaceutical agents into the brain [21]. |

| High-Speed Drill | For performing clean craniotomies in the skull to access the brain surface without causing undue trauma [21]. |

| Active Warming System | A heated pad or controlled circuit board to maintain the rodent's body temperature during anesthesia, preventing hypothermia and improving survival rates [27]. |

| Isoflurane Anesthesia System | A vaporizer and nose cone for delivering inhaled isoflurane, providing stable and controllable surgical anesthesia [27]. |

The meticulous leveling of bregma and lambda to achieve the flat-skull position remains a non-negotiable standard in rigorous stereotaxic surgery. It is the cornerstone upon which the entire Cartesian coordinate system for intracranial navigation is built. While the fundamental principles established by pioneers like Paxinos continue to guide the field, modern innovations in digital atlas technology, automated landmark detection, and refined surgical hardware are pushing the boundaries of precision and reproducibility. For researchers in neuroscience and drug development, a deep understanding and flawless execution of this technique are paramount for generating valid, reliable, and impactful data on brain function and therapeutic intervention.

From Theory to Practice: A Step-by-Step Surgical Protocol for Landmark-Based Targeting

Stereotaxic surgery in rodents is a cornerstone technique in modern neuroscience and drug development research, enabling investigators to target specific brain regions with a high degree of precision. The procedure's success fundamentally relies on a rigorous pre-surgical setup, which encompasses appropriate anesthesia, strict aseptic technique, and the meticulous exposure and preparation of the skull. Within this context, the accurate identification of the bregma and lambda skull landmarks is paramount, as these points form the anatomical basis of the three-dimensional Cartesian coordinate system used for surgical navigation [1] [21]. The bregma, defined as the point of intersection between the sagittal and coronal sutures, serves as the most common origin point (zero point) for stereotaxic coordinates [1] [28]. Despite its critical role, studies highlight that discrepancies in how bregma is measured exist among different laboratories, and renowned atlases like Paxinos and Franklin lack explicit instructions for its determination [1] [28]. This technical guide details the essential pre-surgical procedures, framing them within the critical need for consistent and accurate landmark identification to ensure experimental reproducibility and animal well-being.

Anesthetic Protocols and Physiological Management

Selecting and managing an appropriate anesthetic regimen is the first critical step in rodent stereotaxic surgery. The chosen protocol must provide a sufficient plane of anesthesia for the procedure's duration while minimizing physiological stress on the animal.

Table 1: Common Injectable Anesthetic Protocols for Rodent Stereotaxic Surgery

| Anesthetic Agent(s) | Dosage and Route | Surgical Duration | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ketamine + Xylazine [29] | 40-90 mg/kg (Ketamine) + 5-10 mg/kg (Xylazine), IP | 45-90 minutes | Thermal support is crucial. To prolong anesthesia, supplement with ¼ - ½ dose of ketamine only. Xylazine can be reversed with atipamezole or yohimbine [29]. |

| Ketamine + Dexmedetomidine [29] | 75 mg/kg (Ketamine) + 0.25-0.5 mg/kg (Dexmedetomidine), IP | ~120 minutes | Reversible with atipamezole, facilitating faster recovery. Dosage may be lower if pre-medicated with an opioid [29]. |

| Pentobarbital [29] | 40-50 mg/kg IP for sedation; higher doses for surgery | Variable; poor analgesia | Not recommended as a sole agent due to poor analgesic properties. Can cause significant cardiovascular depression [29]. |

Table 2: Inhaled Anesthetic Protocol for Rodent Stereotaxic Surgery

| Anesthetic Agent | Induction | Maintenance | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Isoflurane [29] [30] | 3-5% in oxygen | 1-3% in oxygen [29] | Requires a calibrated vaporizer and proper gas scavenging. Rapid induction and recovery allow for better control of anesthetic depth [29]. |

Supportive Care and Physiological Monitoring

Preventing hypothermia is a critical aspect of supportive care. Rodents, due to their high surface-area-to-body-mass ratio, are highly susceptible to heat loss under anesthesia. Isoflurane, in particular, promotes hypothermia by inducing peripheral vasodilation [7]. Proactive thermal support is mandatory:

- Allowed Heating Methods: Use a warm circulating water blanket, thermal pad with temperature control, or isothermal heat source. The animal must be separated from the heat source by a towel or drape to prevent burns [29] [30].

- Prohibited Heating Methods: Avoid "over-the-counter" electric heating pads without precise temperature control, as they are prone to overheating [30].

Other essential supportive measures include [29] [30]:

- Eye Lubrication: Apply ophthalmic ointment (e.g., Paralube) to prevent corneal drying for any procedure longer than 5 minutes.

- Hydration: Administer warmed subcutaneous or intraperitoneal fluids (e.g., saline, lactated Ringer's solution at 5-10 ml/kg/hr) during prolonged surgeries to maintain hydration.

Physiological parameters must be monitored regularly (at least every 15 minutes) throughout the procedure [30]:

- Anesthetic Depth: Assessed by loss of response to a firm toe pinch (pedal reflex) and loss of blink reflex.

- Respiratory Function: Monitor rate and effort. A normal undisturbed respiratory rate for a rat is 70-110 breaths per minute; a fall of 50% is acceptable under anesthesia [29].

- Mucous Membranes: Should be pink, not blue (cyanotic), indicating adequate oxygenation.

- Pulse: Can be assessed by palpation of the chest wall.

Figure 1: Anesthetic Management and Monitoring Workflow. This diagram outlines the decision-making process for establishing and maintaining a proper surgical plane of anesthesia while providing essential physiological support.

Aseptic Technique and Surgical Field Preparation

Maintaining asepsis throughout the survival surgical procedure is non-negotiable. It prevents postoperative infections, reduces animal suffering, and ensures that research outcomes are not confounded by pathological variables.

Preoperative Preparation:

- Instrument Sterilization: All surgical instruments must be sterilized prior to the procedure using an approved method (e.g., autoclaving, cold sterilization) [31].

- Surgeon Preparation: The surgeon should don appropriate personal protective equipment (PPE), including a clean lab coat, sterile gloves, mask, and head cover [31].

- Surgical Site Preparation: The rodent's scalp must be shaved and then disinfected with a alternating scrubs of chlorhexidine or povidone-iodine and 70% alcohol, working from the center of the surgical site outward [31].

Sterile Field and Operative Technique:

- The stereotaxic apparatus and surrounding area should be disinfected with 70% alcohol or an appropriate disinfectant wipe [31].

- Use sterile drapes to isolate the surgical site and create a sterile field. Some stereotaxic frames are compatible with dedicated draping kits.

- Handle tissues gently and use sterile instruments to minimize tissue trauma and the risk of contamination.

Skull Exposure and Landmark Identification

With the animal securely positioned in the stereotaxic frame and a stable plane of anesthesia confirmed, the surgical procedure for exposing the skull and identifying critical landmarks begins.

Experimental Protocol: Skull Exposure and Landmark Identification

- Scalp Incision: Using a scalpel, make a midline incision through the skin along the skull, from just behind the eyes to the posterior end of the skull [21].

- Tissue Reflection: Gently separate the underlying connective tissue and muscle from the skull surface using a periosteal elevator or the blunt end of a scalpel handle [21].

- Skull Cleaning: Thoroughly clean the surface of the skull with sterile saline and a cotton-tipped applicator. Any residual tissue or blood can obscure the cranial sutures. Ensure the skull is dry for optimal visualization of the landmarks [32] [21].

- Landmark Identification: Identify the three key sutures under the stereotaxic microscope:

- Sagittal Suture: The prominent suture running along the midline of the skull.

- Coronal Sutures: The sutures that run perpendicular to the sagittal suture, roughly at the level of the eyes.

- Lambdoidal Suture: The suture at the posterior part of the skull that resembles the Greek letter "lambda" (λ) [1].

- Locate Bregma and Lambda:

Table 3: The Scientist's Toolkit - Essential Materials for Pre-surgical Setup

| Item/Category | Specific Examples | Function and Application |

|---|---|---|

| Anesthesia System | Precision vaporizer (for isoflurane), induction chamber, anesthetic machine with oxygen source [29] [30]. | Delivery and control of inhaled anesthetic agents. |

| Stereotaxic Apparatus | Kopf Instruments, RWD Life Science, Harvard Apparatus [1]. | Rigid head fixation and precise 3D navigation. |

| Thermal Support | Circulating warm water blanket, isothermal heating pad (e.g., Gaymar Stryker T/Pump) [7] [29] [30]. | Prevention of hypothermia during surgery and recovery. |

| Surgical Instruments | Scalpel handle and blades, fine forceps, tissue scissors, periosteal elevator, hemostats. | Performing the scalp incision, tissue reflection, and hemostasis. |

| Drilling System | Dental drill with assorted burrs (e.g., 0.5 mm - 1.0 mm). | Creating a clean craniotomy for access to the brain. |

| Skull Fixation | Jeweler's screws, dental acrylic (e.g., Jet Denture Repair Acrylic), dental adhesive (e.g., Super-Bond C&B) [32]. | Securing head-posts and implants to the skull. |

| Disinfectants & Lubricants | Povidone-iodine or chlorhexidine scrub, 70% alcohol, ophthalmic ointment (e.g., Paralube) [29] [30]. | Surgical site preparation and corneal protection. |

The pre-surgical phases of anesthesia, aseptic preparation, and skull exposure constitute the foundational pillars of a successful stereotaxic surgery. The rigorous application of the protocols outlined herein—from the selection of an appropriate anesthetic and diligent physiological monitoring to the maintenance of a sterile field—is essential for ensuring animal welfare and data integrity. Crucially, the entire process culminates in the accurate identification of the bregma and lambda landmarks. As the origin of the stereotaxic coordinate system, the correct setting of the bregma is a non-negotiable step that directly dictates the accuracy of all subsequent surgical interventions [1] [28]. Mastery of these pre-surgical elements not only enhances the wellbeing of the animal subject but also directly contributes to the reproducibility, reliability, and scientific validity of neuroscience and drug development research.

In rodent stereotaxic neurosurgery, the bregma and lambda points on the skull serve as the fundamental anatomical landmarks for establishing a three-dimensional Cartesian coordinate system. This system enables precise navigation to specific brain targets for interventions such as injecting fluids, implanting probes, cannulae, or optic fibers [28]. The advent of the stereotaxic apparatus revolutionized neuroscience research by allowing for this precise 3D navigation along the skull's mediolateral (ML), anteroposterior (AP), and dorsoventral (DV) axes [28]. The accuracy of defining these points is paramount, as even minor errors in setting the bregma as the coordinate origin can propagate into significant targeting inaccuracies, potentially compromising experimental results and their reproducibility [28].

Despite its importance, the specific procedure for measuring bregma is not consistently described across laboratories, and renowned brain atlases often lack explicit instructions for its determination [28]. Furthermore, discrepancies exist between different atlas coordinate systems, and individual anatomical variations between subjects make these points challenging to locate consistently in practice [28] [23]. This guide details both established manual techniques and emerging automated technologies designed to enhance the precision, efficiency, and reliability of bregma and lambda identification.

Established Manual Techniques and Inherent Challenges

The conventional method for identifying bregma and lambda relies on visual inspection and palpation of the rodent skull. Bregma is defined as the point of intersection between the sagittal suture (running along the midline of the skull) and the coronal sutures (which run transversely). Similarly, lambda is the intersection point of the sagittal suture with the lambdoid sutures on the posterior part of the skull [23].

While theoretically straightforward, this manual process involves estimation based on the investigator's experience, which introduces subjectivity and positioning errors [23]. Key challenges include:

- Anatomical Variability: The exact morphology of the skull and suture patterns can vary between individual animals, even within the same strain [23].

- Suture Ambiguity: In some subjects, the suture lines can be faint or partially obscured, making the exact point of intersection difficult to determine with high confidence [23].

- Operator Dependence: The skill and experience of the researcher play a significant role in the accuracy and repeatability of the landmark identification [23].

These challenges underscore the need for rigorous training and standardized protocols to minimize variability when relying on manual techniques.

Automated Detection: A Deep Learning Framework

To overcome the limitations of manual identification, a novel automated framework utilizing deep learning has been developed. This method aims to reduce localization error, improve repeatability, and simplify the procedure [23].

Experimental Protocol for Automated Detection

Dataset Preparation:

- Source: 93 images of sacrificed mice (male and female, age 8-28 weeks, various strains) [23].

- Acquisition: Images were captured using a handheld smartphone (iPhone 6) with dimensions of 2448 × 3264 × 3 pixels, under uncontrolled lighting conditions and mouse orientations to ensure model robustness [23].

- Labeling: An expert neurosurgeon provided the ground-truth coordinates for bregma and lambda on each full-resolution image. For training, these points were represented as 2D Gaussian distributions (standard deviation of 20 pixels) centered on the landmark, transforming the problem into a regression task [23].

Localization Framework Architecture: The framework employs a two-stage deep learning approach [23]:

- Stage One - Skull Detection: A Region-Based Convolutional Neural Network (Faster R-CNN) is used to detect the skull region within the full image. This crops and isolates the Region of Interest (ROI), improving computational efficiency for the next stage [23].

- Stage Two - Landmark Segmentation: A Fully Convolutional Network (FCN) modified with residual networks, bottleneck design, and batch normalization performs pixel-wise segmentation on the cropped skull image. The network outputs two channels representing the probability of each pixel being bregma or lambda. The final coordinates are determined as the pixel with the maximum probability value in each channel [23].

Implementation and Training:

- The 93 images were split into training (n=80) and testing (n=13) sets for the FCN.

- Extensive data augmentation (random flipping, rotating, shifting) was applied to the training set, generating 8000 augmented images from 80 originals to improve model robustness.

- The model was trained to minimize the error between its predicted Gaussian maps and the ground-truth maps provided by the expert [23].

Key Quantitative Performance Data

The automated deep learning framework demonstrated high accuracy in identifying bregma and lambda, as summarized in the table below.

Table 1: Performance Metrics of the Automated Landmark Detection Framework

| Metric | Performance Value | Experimental Context |

|---|---|---|

| Mean Localization Error | < 300 μm [23] | Tested on rodent skull images |

| Model Robustness | Effective under varying lighting conditions and animal orientations [23] | Images captured with handheld smartphone, conditions uncontrolled [23] |

| Skull Detection Rate | 100% in testing (n=33 images) [23] | Stage one Faster R-CNN performance |

This performance is achieved with a model designed to be robust to different lighting conditions and mouse orientations, making it a potentially valuable tool for standardizing stereotaxic procedures [23].

Technical Specifications and Visualization

Experimental Workflow Diagram

The following diagram illustrates the two-stage automated detection process.

Research Reagent Solutions and Essential Materials

A successful experiment, whether manual or automated, relies on specific tools and reagents. The following table details key materials used in the automated detection research.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Automated Landmark Detection

| Item Name | Function / Role in the Experiment | Specifics / Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Rodent Subjects | Source of anatomical skull images for model training and validation. | Mice; various strains, sexes, 8-28 weeks old [23]. |

| Imaging Equipment | Captures high-resolution digital images of the exposed skull. | Handheld smartphone camera (e.g., iPhone 6) [23]. |

| Deep Learning Framework | Provides the software environment for building, training, and deploying the neural networks. | Frameworks supporting Faster R-CNN and FCN implementations (e.g., TensorFlow, PyTorch) [23]. |

| Region-Based CNN (Faster R-CNN) | First-stage neural network model that localizes and crops the skull region from the full image [23]. | -- |

| Fully Convolutional Network (FCN) | Second-stage neural network model that performs pixel-wise segmentation to identify bregma and lambda points [23]. | Modified with residual connections and batch normalization [23]. |

| Data Augmentation Pipeline | Artificially expands the training dataset by applying random transformations, improving model robustness [23]. | Includes random flipping, rotation, and shifting of images [23]. |

| Expert-Annotated Ground Truth | The definitive, accurate coordinates of bregma and lambda used to train and evaluate the model. | Provided by a trained neurosurgeon [23]. |

The precise identification of bregma and lambda is a cornerstone of reproducible rodent stereotaxic surgery. While manual techniques based on skull sutures remain prevalent, they are inherently subjective and susceptible to error. The emergence of automated, deep-learning-based frameworks offers a promising avenue for enhancing the accuracy, reliability, and throughput of this critical step. By achieving sub-300-micron precision and robustness to experimental variability, these technologies have the potential to standardize landmark identification across laboratories, thereby strengthening the validity of neuroscientific and drug development research.

In rodent stereotaxic surgery, the precise targeting of specific brain regions hinges on a Cartesian coordinate system that uses visible landmarks on the skull as its reference points [1]. The Bregma, defined as the point where the sagittal suture intersects the coronal suture, and the Lambda, identified as the intersection of the sagittal and lambdoidal sutures, are the two most critical landmarks for establishing this coordinate system [1] [21]. The primary origin for stereotaxic coordinates is most commonly the Bregma [1]. However, the accuracy of these coordinates is entirely dependent on the skull being positioned in a level plane. If the skull is tilted, the same set of coordinates will target a different, and incorrect, location in the brain. Therefore, the procedure of using a micromanipulator to ensure that Bregma and Lambda are at the same height along the dorsoventral axis is not merely a preliminary step; it is a fundamental prerequisite for ensuring the reproducibility and validity of any stereotaxic intervention, from viral vector injections to electrode implantations [21].

Recent studies continue to highlight that discrepancies in the measurement of these skull landmarks are a significant source of error in neuroscience research [1]. This technical guide will detail the leveling procedure, framing it within the broader context of a thesis on rodent cranial landmarks, and provide the detailed methodologies and tools required to execute it with precision.

Essential Concepts: Bregma, Lambda, and the Stereotaxic Frame

Anatomical Definitions and Their Significance

The adult rodent skull is composed of several bones that meet at joints known as sutures. For stereotaxic surgery, three key sutures are visible from a dorsal view [1]:

- Sagittal Suture: Runs medially along the midline of the skull, separating the two parietal bones.

- Coronal Suture: Has a parabolic curve between the frontal and parietal bones.

- Lambdoidal Suture: Resembles the Greek letter Lambda (λ) at the posterior part of the skull, between the parietal bones and the occipital bone.

The intersections of these sutures define our critical landmarks [1] [21]:

- Bregma: The point where the sagittal suture crosses the coronal suture. This is the most common origin point for the stereotaxic coordinate system.

- Lambda: The point where the sagittal suture crosses the lambdoidal suture.

The line connecting Bregma and Lambda defines the anteroposterior (AP) axis. Ensuring both points are at the same height in the dorsoventral (DV) axis confirms the skull is level in the AP plane.

Table 1: Key Skull Landmarks in Rodent Stereotaxic Surgery

| Landmark | Anatomical Definition | Role in Stereotaxic Surgery |

|---|---|---|

| Bregma | Intersection of the sagittal and coronal sutures | Most common origin point (zero point) for stereotaxic coordinates. |

| Lambda | Intersection of the sagittal and lambdoidal sutures | Used in conjunction with Bregma to level the skull and define the anteroposterior axis. |

| Sagittal Suture | Midline suture between the parietal bones | Provides a visual reference for medial-lateral alignment. |

The Stereotaxic Apparatus and Micromanipulator

The stereotaxic frame is the instrument that holds the animal's head in a fixed position. Its key components include [21]:

- Base Plate: The horizontal platform on which the animal is positioned.

- Ear Bars: Secure the animal's head by being gently placed in the external auditory meatus.

- Incisor Bar: Holds the animal's front teeth to stabilize the head.

- Micromanipulator: A precise moving assembly attached to the frame. It holds surgical probes, electrodes, or syringes and allows for controlled movement along the three Cartesian axes: mediolateral (ML), anteroposterior (AP), and dorsoventral (DV) [1] [21]. The manipulator is equipped with Vernier scales or digital readouts for exact distance measurements.

The Leveling Procedure: A Step-by-Step Technical Guide