Biochemical Assays for Intracellular Signaling Analysis: From Foundational Principles to Advanced Applications in Drug Discovery

This article provides a comprehensive resource for researchers and drug development professionals on the application of biochemical assays for intracellular signaling analysis.

Biochemical Assays for Intracellular Signaling Analysis: From Foundational Principles to Advanced Applications in Drug Discovery

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive resource for researchers and drug development professionals on the application of biochemical assays for intracellular signaling analysis. It covers the foundational principles of key signaling pathways, including GPCR, MAPK, and JAK/STAT cascades, and details a wide array of methodological approaches from traditional second messenger assays to modern high-throughput and high-content screening platforms. The content further addresses critical troubleshooting and optimization strategies to ensure assay robustness and reproducibility, and concludes with rigorous validation and comparative analysis frameworks. By integrating current methodologies with emerging trends in quantitative proteomics, transcriptomics, and 3D culture systems, this guide aims to enhance the efficiency and success of target validation and therapeutic development in precision medicine.

Understanding Intracellular Signaling Pathways: Core Principles and Therapeutic Targets

Intracellular second messengers are small molecules and ions that relay signals from cell surface receptors to target molecules within the cell, amplifying signals and regulating diverse physiological responses. This application note focuses on four key second messengers—cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP), calcium ions (Ca²⁺), inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate (IP3), and diacylglycerol (DAG)—that play central roles in cellular signal transduction. These messengers translate extracellular stimuli into precise cellular actions through complex networks, making them critical targets for research and drug development [1] [2].

Understanding the dynamics of these signaling systems requires specialized biochemical assays capable of capturing their rapid, compartmentalized changes within cells. This note provides detailed methodologies for monitoring these messengers, framed within the context of biochemical assay development for intracellular signaling analysis. We present quantitative data comparisons, structured experimental protocols, and visual workflow representations to support researchers in implementing these techniques effectively.

Key Second Messengers: Mechanisms and Biological Roles

Cyclic AMP (cAMP)

cAMP is a ubiquitous second messenger synthesized from ATP by adenylyl cyclase (AC) upon activation of G-protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs). Its production is regulated by stimulatory (Gαs) and inhibitory (Gαi) G-protein subunits, while its degradation is primarily mediated by phosphodiesterases (PDEs) that hydrolyze it to 5'-AMP [3]. cAMP functions principally by activating protein kinase A (PKA), which phosphorylates serine/threonine residues on target proteins including the transcription factor CREB (cAMP response element-binding protein) that regulates gene expression [3]. Additionally, cAMP activates exchange proteins directly activated by cAMP (EPAC), influencing cell adhesion, exocytosis, differentiation, and proliferation [4] [3].

Spatiotemporal control of cAMP signaling is maintained through compartmentalization into multiprotein complexes organized by A-kinase anchoring proteins (AKAPs), which tether PKA with specific effectors, phosphodiesterases, and phosphatases to create localized signaling microdomains [3]. This compartmentalization ensures signaling specificity despite cAMP's involvement in numerous pathways.

Biological Implications: cAMP signaling exhibits paradoxical roles in cancer—promoting tumor growth, invasion, and therapy resistance in some contexts while suppressing migration in others [3]. In the nervous system, cAMP regulates neuronal growth, synaptic plasticity, and memory formation, with disruptions linked to neurodevelopmental and neurodegenerative disorders [3]. In immunity, cAMP generally exerts anti-inflammatory effects, dampening pro-inflammatory cytokine release and promoting resolution of inflammation [3].

Calcium Ions (Ca²⁺)

Calcium ions serve as versatile signaling messengers regulating processes from fertilization and development to metabolism, secretion, muscle contraction, and neural functions including learning and memory [2]. Intracellular Ca²⁺ levels are tightly regulated, with cytosolic concentrations maintained at approximately 0.1 μM against extracellular concentrations orders of magnitude higher. Calcium is stored in intracellular compartments like the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) and sarcoplasmic reticulum (SR) [5].

Ca²⁺ signaling occurs through transient increases in cytosolic concentration, often through release from ER stores via channels including IP3 receptors (IP3Rs) and ryanodine receptors (RyRs) [6] [5]. These increases regulate numerous target proteins, including protein kinases, phosphatases, and calcium-binding proteins, which transduce the signal into cellular responses.

Research Applications: Advanced detection methods like total internal reflection fluorescence (TIRF) microscopy enable visualization of localized Ca²⁺ release events ("Ca²⁺ puffs") with high spatial and temporal resolution, providing insights into fundamental signaling mechanisms [7].

Inositol 1,4,5-Trisphosphate (IP3) and Diacylglycerol (DAG)

IP3 and DAG are second messengers generated concurrently through hydrolysis of the membrane phospholipid phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate (PIP₂) by phospholipase C (PLC) [5]. This reaction is activated downstream of both GPCRs and receptor tyrosine kinases (RTKs) [5].

IP3 is water-soluble and diffuses through the cytosol to bind ligand-gated calcium channels (IP3 receptors) on the ER membrane, triggering Ca²⁺ release into the cytosol [6] [5]. This IP3-induced calcium release regulates various calcium-dependent processes and can further amplify signaling through calcium-induced calcium release mechanisms [5].

DAG remains membrane-associated due to its hydrophobic properties and functions primarily by activating protein kinase C (PKC) isoforms [5]. DAG also serves as a source for prostaglandin synthesis, a precursor for the endocannabinoid 2-arachidonoylglycerol, and an activator of TRPC cation channels [5].

The IP3/DAG pathway exemplifies signal divergence, where a single initial stimulus (PIP₂ hydrolysis) generates two distinct messengers that regulate parallel signaling branches—calcium mobilization and PKC activation—which often converge to regulate downstream cellular responses synergistically.

Table 1: Key Characteristics of Major Second Messengers

| Second Messenger | Precursor | Primary Activator | Key Effectors | Primary Functions |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| cAMP | ATP | Adenylyl cyclase | PKA, EPAC, CNG/HCN channels | Metabolic regulation, gene expression, cardiac contractility, neurotransmission |

| Ca²⁺ | ER stores, extracellular space | IP3R, RyR channel opening | Calmodulin, CaMK, PKC | Muscle contraction, secretion, synaptic plasticity, proliferation |

| IP3 | PIP₂ | Phospholipase C | IP3 receptor (calcium channel) | Calcium release from ER, regulation of calcium-dependent processes |

| DAG | PIP₂ | Phospholipase C | PKC, TRPC channels | Cell growth, differentiation, proliferation, exocytosis |

Quantitative Analysis of Second Messenger Dynamics

Understanding the quantitative behavior of second messengers is essential for deciphering their biological functions. The table below summarizes key quantitative parameters for the featured second messengers, based on current research findings.

Table 2: Quantitative Parameters of Second Messenger Systems

| Second Messenger | Detection Method | Dynamic Range | Key Kinetic Parameters | Reference System |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| cAMP | FRET-based biosensors (EPAC*) | 150 nM - 15 μM | FRET efficiency: 35% (low cAMP) to 20% (high cAMP) ΔE = 15% | N1E-115 neuroblastoma cells [4] |

| Ca²⁺ | TIRF microscopy with Cal-520 | N/A | High temporal resolution (ms); subcellular spatial resolution | HEK-293 cells [7] |

| IP3 | Caged compounds with photo-uncaging | N/A | Controlled temporal release; resistant to degradation (ci-IP3-PM) | DT40 cells expressing IP3R subtypes [6] |

Experimental Protocols for Second Messenger Analysis

FRET-Based Measurement of cAMP Concentrations

This protocol describes a robust method for quantitative measurement of intracellular cAMP concentration using Förster resonance energy transfer (FRET)-based biosensors, adapted from published methodology [4].

Principle

The method employs an Epac1-based biosensor (EPAC*) where cAMP binding induces conformational changes altering FRET efficiency between cyan (eCFP) and yellow (eYFP) fluorescent proteins. Using two-excitation wavelength spectral FRET analysis accounts for environmental factors affecting fluorophore folding, enabling quantitative cAMP measurement without additional calibration [4].

Materials

- Plasmids: cDNA encoding eCFP-Epac(δDEP-CD)-eYFP (EPAC*) in pcDNA3 vector [4]

- Cell Line: N1E-115 neuroblastoma cells (or other adherent cell types)

- Transfection Reagent: Lipofectamine2000

- Imaging Equipment: Fluorescence spectrometer or microscope capable of dual-excitation measurements (e.g., Fluorolog-322)

- Buffers: Intracellular solution (140 mM KCl, 5 mM NaCl, 1 mM MgCl₂, 10 mM HEPES, pH 7.2)

Procedure

Cell Culture and Transfection:

- Culture N1E-115 cells in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium with 10% fetal calf serum at 37°C under 5% CO₂.

- Seed cells at low density (1×10⁶ cells) in 60 mm dishes or on glass coverslips 24 hours before transfection.

- Transfect with EPAC* plasmid using Lipofectamine2000 according to manufacturer's instructions.

- Serum-starve cells overnight before analysis to enhance response.

Sample Preparation:

- Wash transfected cells three times with intracellular solution.

- Homogenize cells in 2.3 mL intracellular solution using a homogenizer at 2500 rpm for 2 minutes.

- Centrifuge homogenate at 21,000 × g for 1 minute at 4°C.

- Transfer supernatant to quartz cuvettes equipped with magnetic stirrer.

Spectral FRET Measurements:

- Perform measurements in 1 nm wavelength steps with 2 nm spectral resolution.

- Use front-face arrangement to minimize scattering and reabsorption.

- Record emission spectra with excitation at both 420 nm and optimal donor/acceptor wavelengths.

- Collect reference spectra from empty vector-transfected cells for background subtraction.

Data Analysis:

- Fit measured spectra as linear combinations of eCFP and eYFP reference spectra.

- Calculate apparent FRET efficiency from donor/acceptor emission ratios.

- Determine cAMP concentration from calibration curve relating FRET efficiency to [cAMP].

Applications

This method enables spatially resolved quantitative measurement of dynamic cAMP changes, applicable to studying GPCR signaling, such as Gs-coupled serotonin receptor (5-HT7) activation in neuroblastoma cells [4].

Detection of Elemental Calcium Signals (Ca²⁺ Puffs)

This protocol outlines steps to visualize and detect localized Ca²⁺ release events (puffs) following photo-liberation of caged IP3 using total internal reflection fluorescence (TIRF) microscopy [7].

Principle

TIRF microscopy provides high axial resolution and signal-to-background ratio for imaging near the plasma membrane. Photo-uncaging of membrane-permeant caged IP3 (ci-IP3-PM) induces Ca²⁺ release through IP3 receptors, visualized using the high-performance calcium indicator Cal-520.

Materials

- Cell Line: HEK-293 cells expressing native IP3R type 1 ("endo hR1 cells")

- Calcium Indicator: Cal-520-AM (1 mM stock in DMSO)

- Caged IP3: ci-IP3-PM (1 mM stock in DMSO)

- Calcium Buffer: EGTA-AM (10 mM stock in DMSO)

- Imaging System: TIRF microscope with 488 nm laser excitation and UV uncaging system

- Imaging Buffer: Hanks' Balanced Salt Solution (HBSS: 137 mM NaCl, 0.56 mM MgCl₂, 4.7 mM KCl, 1 mM Na₂HPO₄, 10 mM HEPES, 5.5 mM glucose, 1.26 mM CaCl₂, pH 7.4)

Procedure

Cell Preparation:

- Culture endo hR1 cells in DMEM with 10% FBS at 37°C under 5% CO₂.

- Passage cells at least twice after thawing before experiments.

- Seed cells on glass-bottom dishes at 30-50% confluence 24-48 hours before imaging.

Dye Loading and Reagent Incubation:

- Prepare loading solution: 2-5 μM Cal-520-AM, 1-2 μM ci-IP3-PM, and 10-20 μM EGTA-AM in HBSS.

- Incubate cells with loading solution for 30-45 minutes at room temperature protected from light.

- Wash cells twice with fresh HBSS to remove extracellular dye.

TIRF Microscopy and Photo-uncaging:

- Mount dish on TIRF microscope stage maintained at 35-37°C.

- Focus on cell basal membrane using 488 nm laser at low intensity.

- Acquire baseline images at high speed (≥10 fps) for 10-30 seconds.

- Apply brief UV flash (1-100 ms) to uncage IP3 while continuing acquisition.

- Record for additional 1-5 minutes to capture Ca²⁺ puff dynamics.

Data Analysis:

- Identify Ca²⁺ puffs as localized, transient fluorescence increases (ΔF/F₀) using automated detection algorithms.

- Determine puff kinetics: amplitude, rise time, full width at half maximum, and spatial spread.

- Analyze puff frequency and distribution under different experimental conditions.

Technical Notes

- Cal-520 offers superior quantum efficiency and signal-to-noise ratio compared to other green calcium indicators.

- EGTA-AM limits recruitment of neighboring IP3R clusters, improving spatial resolution.

- Avoid photo-damage by minimizing laser exposure and using lowest effective UV intensity.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Research Reagents for Second Messenger Studies

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Function/Application | Experimental Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| FRET Biosensors | eCFP-Epac(δDEP-CD)-eYFP (EPAC*) | Quantitative cAMP measurement | Excitation at 420 nm; ΔE = 15% between high/low cAMP [4] |

| cAMP Pathway Modulators | Gαs-coupled receptor agonists, PDE inhibitors (BPN14770) | Manipulate cAMP levels; study pathway function | PDE4D inhibition shows clinical benefit in Fragile X syndrome [3] |

| Calcium Indicators | Cal-520-AM | High-performance green calcium indicator | Superior quantum efficiency, signal-to-noise ratio, intracellular retention [7] |

| Caged Compounds | ci-IP3-PM (cell-permeant caged IP3) | Precise temporal control of IP3 delivery | Poorly metabolizable; UV uncaging releases active IP3 [7] |

| IP3R Agonists | Adenophostin A, d-chiro-inositol analogs | Potent IP3R activation; study receptor pharmacology | 10-fold more potent than endogenous IP3; activates all IP3R subtypes [6] |

| Cell Lines | HEK-293 endo hR1, N1E-115 neuroblastoma | Model systems for signaling studies | Genetically engineered to express specific IP3R subtypes [7] |

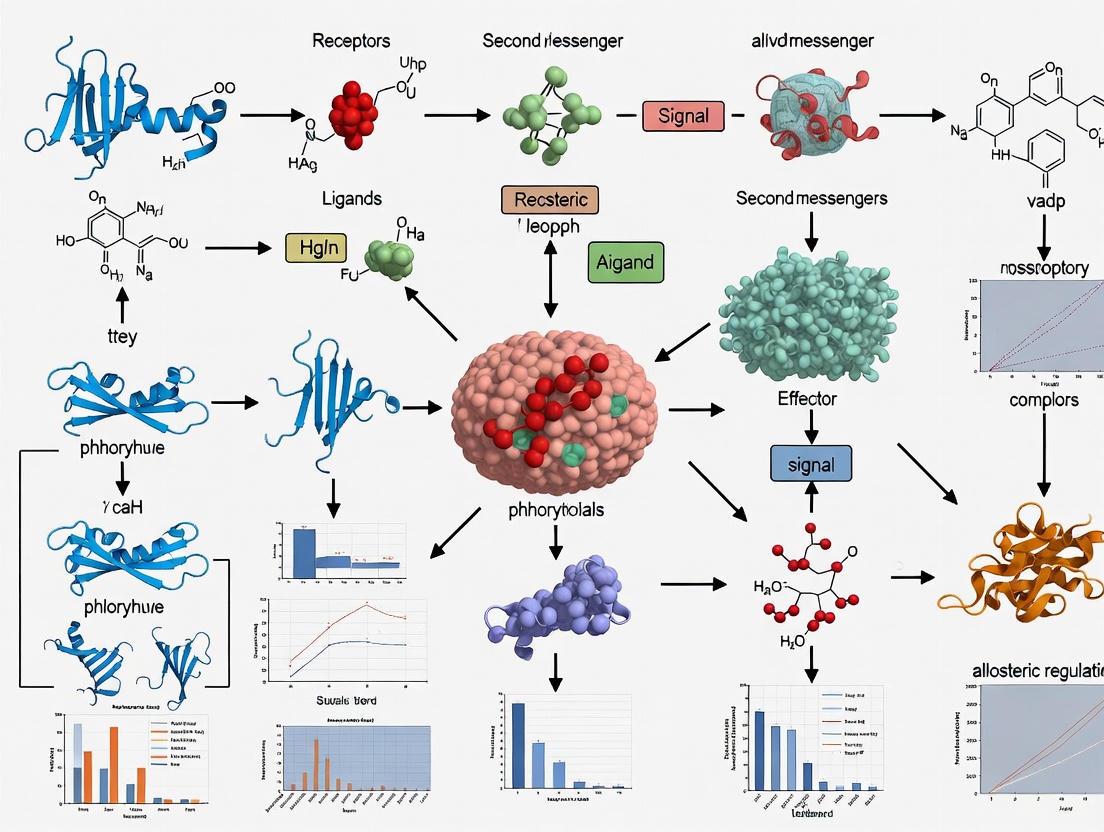

Signaling Pathway Visualizations

Second Messenger Signaling Pathways

Experimental Workflow for Second Messenger Detection

Concluding Remarks

The intricate networks of intracellular second messengers represent fundamental communication systems that coordinate cellular behavior in health and disease. The experimental approaches detailed in this application note—FRET-based cAMP biosensing and TIRF microscopy for calcium puff detection—provide powerful methodologies for quantifying the spatiotemporal dynamics of these signaling molecules with high precision.

These techniques enable researchers to move beyond static snapshots of signaling states toward dynamic understanding of how information flows through cellular networks. This is particularly relevant for drug development, where understanding the temporal and compartmentalized nature of second messenger signaling can inform more targeted therapeutic strategies with reduced off-target effects.

Future directions in second messenger research will likely involve increased integration of multiple detection modalities to simultaneously monitor several messengers, further development of genetically encoded biosensors with improved sensitivity and dynamic range, and application of these tools in more physiologically relevant model systems including 3D organoids and in vivo preparations.

Intracellular signaling pathways form the cornerstone of cellular communication, governing critical processes such as proliferation, differentiation, inflammation, and apoptosis. In the realm of drug discovery, understanding these pathways is paramount for developing targeted therapies for a wide spectrum of diseases, including cancer, autoimmune disorders, and neurodegenerative conditions. This article provides a detailed overview of four major signaling pathways—GPCRs, MAPK, JAK/STAT, and NF-κB—within the context of biochemical assays for intracellular signaling analysis. We present comprehensive application notes and experimental protocols tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, facilitating the investigation and therapeutic targeting of these pivotal pathways.

Pathway Fundamentals and Disease Relevance

G Protein-Coupled Receptors (GPCRs)

GPCRs represent the largest superfamily of cell surface membrane receptors, encoded by approximately 1000 genes in humans and characterized by a conserved seven-transmembrane (7TM) helix structure [8]. These receptors transduce diverse extracellular signals—including photons, ions, lipids, neurotransmitters, hormones, and peptides—into intracellular responses [8]. Upon agonist binding, GPCRs undergo conformational changes that trigger the exchange of GDP for GTP on the associated Gα subunit, leading to dissociation of the Gα from the Gβγ dimer [8] [9]. The activated G protein subunits then initiate downstream signaling cascades through various effector proteins. Notably, approximately 34% of FDA-approved drugs target GPCRs, underscoring their tremendous therapeutic importance [8].

Mitogen-Activated Protein Kinase (MAPK) Pathway

The MAPK pathway comprises serine/threonine protein kinases that convert extracellular stimuli into diverse cellular responses [10]. This pathway is activated by various factors, including reactive oxygen species (ROS), growth factors, and stress stimuli, regulating fundamental processes such as cell proliferation, differentiation, and apoptosis [11] [10]. In skin aging and cancer, overactivation of the p38/MAPK signaling pathway leads to collagen degradation, extracellular matrix disruption, and excessive inflammatory factor release [11] [10]. The pathway demonstrates significant interplay with autophagy processes, creating complex regulatory networks that influence disease progression and therapeutic outcomes [10].

Janus Kinase/Signal Transducer and Activator of Transcription (JAK/STAT) Pathway

Discovered more than a quarter-century ago, the JAK/STAT pathway functions as a rapid membrane-to-nucleus signaling module [12]. This pathway is activated by more than 50 cytokines and growth factors, including interferons, interleukins, and colony-stimulating factors [12]. The pathway consists of three main components: cellular receptors, JAK proteins (JAK1, JAK2, JAK3, TYK2), and STAT proteins (STAT1, STAT2, STAT3, STAT4, STAT5a, STAT5b, STAT6) [12] [13]. Dysregulation of JAK/STAT signaling is associated with various cancers and autoimmune diseases, making it a promising target for therapeutic intervention [12] [14]. Natural products have demonstrated significant potential in modulating this pathway through mechanisms such as inhibiting JAK/STAT phosphorylation, blocking STAT dimerization, and interfering with STAT-DNA binding [13].

Nuclear Factor Kappa B (NF-κB) Pathway

First identified in 1986, NF-κB is a transcription factor that binds to the kappa enhancer of the gene encoding the κ light-chain of immunoglobulin in B cells [15]. The mammalian NF-κB transcription factor family comprises five members: NF-κB1 (p105/p50), NF-κB2 (p100/p52), p65 (RELA), RELB, and c-REL [15]. NF-κB activation occurs through canonical, alternative, or atypical pathways in response to diverse stimuli such as pro-inflammatory cytokines, bacterial toxins, viral products, and cell death stimuli [16] [15]. This pathway controls gene expression of numerous pro-inflammatory mediators and regulates genes involved in tumorigenesis, metastasis, proliferation, and apoptosis [16]. NF-κB's involvement in inflammation, immune regulation, and the tumor microenvironment underscores its significance as a therapeutic target [15].

Table 1: Core Components of Major Signaling Pathways in Drug Discovery

| Pathway | Key Components | Primary Activators | Cellular Processes Regulated | Therapeutic Areas |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| GPCRs | ~800 GPCRs, Gα (Gs, Gi/o, Gq/11, G12/13), Gβγ, GRKs, β-arrestins | Photons, ions, lipids, neurotransmitters, hormones, peptides [8] | Sensory perception, neurotransmission, endocrine processes [8] | Cardiovascular disease, neurological disorders, metabolic diseases [8] |

| MAPK | p38, JNK, ERK | ROS, growth factors, stress stimuli, UV radiation [11] [10] | Proliferation, differentiation, apoptosis, collagen degradation [11] [10] | Cancer, inflammatory diseases, skin aging [11] [10] |

| JAK/STAT | JAK1-3, TYK2, STAT1-6, cytokine receptors | Interferons, interleukins, colony-stimulating factors [12] | Hematopoiesis, immune responses, proliferation, apoptosis [12] [13] | Autoimmune diseases, leukemias, lymphomas, breast cancers [12] [14] |

| NF-κB | p50, p52, p65, RELB, c-REL, IκB, IKK complex | TNF-α, IL-1, LPS, viral products, UV radiation [16] [15] | Inflammation, immune regulation, apoptosis, tumorigenesis [16] [15] | Inflammatory diseases, cancer, autoimmune disorders [15] |

Quantitative Analysis and Detection Methods

Advanced detection methodologies are essential for quantifying signaling pathway activity and evaluating therapeutic interventions. The following section outlines key experimental approaches for analyzing these pathways.

GPCR Signaling Assays

GPCR signaling can be quantified using multiple approaches that measure different activation stages. Ligand-binding assays utilize radiolabeled or fluorescent-tagged ligands to assess receptor binding affinity and kinetics [9]. Conformational change sensors detect agonist-induced receptor activation through fluorescence changes [9]. G protein activation is commonly measured using GTP binding assays, cAMP assays for Gs/Gi-coupled receptors, inositol-phosphate (IP) accumulation assays for Gq-coupled receptors, and calcium mobilization assays [17] [9]. β-arrestin recruitment is typically assessed using BRET (Bioluminescence Resonance Energy Transfer) or FRET (Förster Resonance Energy Transfer) techniques, which rely on energy transfer between donor and acceptor molecules when in close proximity (<10 nm) [17] [9]. Additionally, transcriptional reporter assays monitor pathway activation through downstream gene expression changes [9].

MAPK Pathway Detection

MAPK pathway activity is frequently analyzed using phospho-specific antibodies targeting phosphorylated forms of p38, JNK, or ERK via Western blotting or immunofluorescence [11]. High-content imaging systems can quantify the subcellular localization and activation status of MAPK components [11]. For apoptosis detection within the MAPK pathway, TUNEL assays measure DNA fragmentation, while Western blotting analysis of pro-apoptotic (p53, Bax, caspase-3) and anti-apoptotic (Bcl-2) proteins provides additional mechanistic insights [11]. Functional assays such as cell viability (CCK-8), clonogenic survival, and migration assays (scratch wound healing, Transwell) evaluate the phenotypic consequences of MAPK pathway modulation [11].

JAK/STAT Pathway Analysis

JAK/STAT activation is commonly detected through phosphorylation status of JAKs and STATs using phospho-specific flow cytometry or Western blotting [12] [13]. STAT dimerization and nuclear translocation can be visualized via immunofluorescence microscopy [13]. DNA binding activity is measured using Electrophoretic Mobility Shift Assays (EMSAs) or reporter gene assays [13]. Gene expression profiling of downstream targets (e.g., SOCS proteins) provides functional readouts of pathway activity [12]. The RNAscope assay offers an ultra-sensitive method for detecting low-abundance transcripts of pathway components, serving as an alternative to antibody-based detection [14].

NF-κB Translocation Assay

NF-κB activation is predominantly assessed through its translocation from the cytoplasm to the nucleus. The High Content Screening (HCS) assay utilizes automated fluorescent microscopy to quantify this translocation [16]. Cells are stained with a nuclear dye (Hoechst, DAPI, or DRAQ5) and antibodies against NF-κB p65 subunit [16]. Image analysis algorithms create nuclear and cytoplasmic masks, calculating translocation values as either the difference (Cyto-Nuc Difference) or ratio (Nuc/Cyt Ratio) of NF-κB intensity between these compartments [16]. This approach can be multiplexed with other biofluorescent probes to simultaneously measure additional signaling nodes or viability markers [16].

Table 2: Quantitative Assays for Signaling Pathway Analysis

| Assay Category | Specific Assays | Measured Parameters | Applications | Key Reagents |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Binding & Activation | Radioligand binding, FRET/BRET conformational sensors | Receptor-ligand affinity, conformational changes [9] | Compound screening, mechanism of action studies [9] | Radiolabeled ligands, fluorescent-tagged ligands [9] |

| Second Messenger | cAMP assay, IP accumulation, calcium flux | G protein activation, downstream signaling [17] [9] | Pathway mapping, receptor coupling efficiency [9] | cAMP analogs, ionomycin, thapsigargin [9] |

| Translocation | High-content imaging, immunofluorescence | Protein subcellular localization (e.g., NF-κB, STATs) [16] [13] | Nuclear translocation studies, activation kinetics [16] | NF-κB p65 antibodies, STAT antibodies, nuclear dyes [16] |

| Transcriptional Activity | Reporter gene assays, RNAscope | Downstream gene expression, pathway activity [13] [14] | Functional pathway readout, target engagement [9] [14] | Luciferase constructs, fluorescent reporters, target-specific probes [9] [14] |

| Phenotypic Assays | Cell viability, migration, apoptosis | Functional cellular responses [11] | Efficacy assessment, toxicity profiling [11] | CCK-8 reagents, TUNEL assay kits, matrix proteins [11] |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: NF-κB Translocation Assay Using High Content Screening

Principle: This assay quantifies cytokine-induced translocation of NF-κB (p65 subunit) from the cytoplasm to the nucleus in fixed cells using automated fluorescent microscopy and image analysis [16].

Reagents:

- Cell line (e.g., HeLa cells)

- Proinflammatory cytokines (IL-1α or TNF-α)

- Fixative (e.g., 4% paraformaldehyde)

- Permeabilization buffer (e.g., 0.1% Triton X-100)

- Blocking buffer (e.g., 1-5% BSA in PBS)

- Primary antibody: anti-NF-κB p65

- Secondary antibody: fluorophore-conjugated (e.g., Alexa Fluor 488)

- Nuclear stain: Hoechst 33342, DAPI, or DRAQ5

- Reference control inhibitor: IKK inhibitor (e.g., BMS-345541)

Procedure:

- Cell Seeding and Treatment: Seed cells in 96-well microplates at optimal density (e.g., 10,000-20,000 cells/well) and culture overnight. Stimulate cells with IL-1α (0.1-10 ng/mL) or TNF-α (1-50 ng/mL) for 5-30 minutes to activate NF-κB pathway. Include DMSO vehicle control and IKK inhibitor control (pre-treated for 1 hour) [16].

- Cell Fixation and Staining: Fix cells with 4% paraformaldehyde for 15 minutes at room temperature. Permeabilize with 0.1% Triton X-100 for 10 minutes. Block with 1-5% BSA for 30-60 minutes. Incubate with anti-NF-κB p65 primary antibody (diluted in blocking buffer) for 2 hours at room temperature or overnight at 4°C. Wash 3× with PBS. Incubate with fluorophore-conjugated secondary antibody and nuclear stain for 1 hour at room temperature protected from light. Perform final PBS washes [16].

- Image Acquisition and Analysis: Acquire images using high-content imaging system with 20× or 40× objective. Acquire 4-9 fields per well to ensure adequate cell counting (≥1000 cells/well). Use appropriate filter sets for nuclear stain and NF-κB signal. Perform image analysis using translocation algorithm: identify nuclei based on nuclear stain; create cytoplasmic mask; measure mean NF-κB intensity in nucleus and cytoplasm; calculate translocation index as Nuc/Cyt Ratio or Cyto-Nuc Difference [16].

- Data Analysis: Export well-level summary data for statistical analysis. Calculate Z-factor to assess assay quality: Z-factor = 1 - (3×SDmax + 3×SDmin) / |Meanmax - Meanmin|, where max = cytokine-stimulated control and min = inhibitor or unstimulated control. Z-factor > 0.5 indicates excellent assay quality [16].

Protocol 2: GPCR G Protein Activation Using BRET-Based Sensor

Principle: This assay measures real-time G protein activation by monitoring agonist-induced dissociation of Gα and Gβγ subunits using Bioluminescence Resonance Energy Transfer (BRET) [9].

Reagents:

- Cells expressing GPCR of interest

- Gα-Rluc8 and Gβγ-GFP2 constructs

- GPCR agonists and antagonists

- Coelenterazine h substrate (5 μM)

- Assay buffer (e.g., HBSS with 0.1% BSA)

Procedure:

- Cell Preparation and Transfection: Culture cells in appropriate medium. Transfect with Gα-Rluc8 and Gβγ-GFP2 constructs using preferred transfection method. For optimal results, maintain 1:3 ratio of Gα-Rluc8:Gβγ-GFP2 DNA. Include untransfected cells for background correction. Allow 24-48 hours for protein expression [9].

- BRET Measurements: Harvest cells and resuspend in assay buffer at 0.5-1×10^6 cells/mL. Distribute cell suspension in white 96-well plates (80-100 μL/well). Add compounds (agonists/antagonists) to test wells. Initiate BRET measurement by adding coelenterazine h (final concentration 5 μM). Immediately measure luminescence and fluorescence using compatible microplate reader with filters for Rluc8 (485 ± 20 nm) and GFP2 (530 ± 20 nm). Take readings every 1-2 seconds for 2-5 minutes to capture rapid kinetics [9].

- Data Analysis: Calculate BRET ratio as (emission at 530 nm) / (emission at 485 nm). Subtract BRET ratio from cells expressing Rluc8 donor alone. Plot corrected BRET ratio versus time. Determine area under the curve (AUC) or maximum response for concentration-response curves. Fit data to appropriate model (e.g., four-parameter logistic equation) to calculate EC50/IC50 values [9].

Protocol 3: JAK/STAT Phosphorylation Analysis by Phospho-Flow Cytometry

Principle: This protocol enables quantitative analysis of STAT phosphorylation at single-cell resolution using antibody-based detection and flow cytometry, allowing for multiplexed analysis of multiple phospho-proteins simultaneously [12] [13].

Reagents:

- Single-cell suspension from culture or primary tissue

- Serum-free medium for starvation

- Cytokine stimulants (e.g., IFN-γ, IL-6)

- JAK inhibitors (e.g., ruxolitinib) for controls

- Fixation buffer (e.g., 4% paraformaldehyde)

- Permeabilization buffer (e.g., 100% methanol or commercial perm buffers)

- Phospho-specific antibodies (e.g., anti-pSTAT1, pSTAT3, pSTAT5)

- Fluorescently-labeled secondary antibodies (if using indirect detection)

- Flow cytometry staining buffer (PBS with 1-5% FBS)

Procedure:

- Cell Stimulation and Fixation: Starve cells in serum-free medium for 2-4 hours to reduce basal phosphorylation. Stimulate with cytokines (e.g., IFN-γ at 10-100 ng/mL) for 15-30 minutes at 37°C. Include unstimulated controls and inhibitor-treated controls (pre-incubate with JAK inhibitor for 1-2 hours). Immediately fix cells with 4% paraformaldehyde for 10-15 minutes at room temperature. Wash cells with flow cytometry staining buffer [12] [13].

- Cell Permeabilization and Staining: Permeabilize cells with ice-cold 100% methanol for 30 minutes on ice or overnight at -20°C. Alternatively, use commercial permeabilization buffers according to manufacturer's instructions. Wash cells twice with staining buffer. Incubate with phospho-specific primary antibodies (optimally titrated) for 30-60 minutes at room temperature. For indirect detection, wash cells and incubate with fluorescently-labeled secondary antibodies for 30 minutes protected from light [13].

- Flow Cytometry Acquisition and Analysis: Resuspend cells in staining buffer and acquire data on flow cytometer with appropriate laser and filter configurations. Include single-stained controls for compensation. Collect ≥10,000 events per sample. Analyze data using flow cytometry software. Gate on live, single cells. Measure median fluorescence intensity (MFI) of phospho-STAT staining. Calculate fold change in MFI relative to unstimulated controls [13].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Signaling Pathway Analysis

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function | Application Examples |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cell Line Models | HeLa (NF-κB translocation), HEK293 (GPCR signaling), HepG2 (MAPK apoptosis), Primary immune cells (JAK/STAT) [16] [11] [13] | Provide biologically relevant systems for pathway manipulation and compound screening | NF-κB translocation assay [16], Liver cancer apoptosis studies [11] |

| Detection Antibodies | Phospho-specific STAT antibodies, NF-κB p65 antibodies, Phospho-p38 antibodies [16] [11] [13] | Detect protein expression, localization, and post-translational modifications | Phospho-flow cytometry, Western blotting, Immunofluorescence [16] [11] [13] |

| FRET/BRET Components | Rluc8, GFP2, Coelenterazine h substrate [9] | Enable real-time monitoring of protein-protein interactions and conformational changes | GPCR G protein dissociation assays [9] |

| Pathway Modulators | IKK inhibitors (BMS-345541), JAK inhibitors (ruxolitinib), p38 inhibitors (SB203580) [16] [13] | Activate or inhibit specific pathway nodes for mechanistic studies and control experiments | NF-κB assay validation [16], JAK/STAT pathway inhibition [13] |

| High-Content Imaging Reagents | Hoechst 33342, DAPI, DRAQ5, CellMask stains [16] | Enable cellular and subcellular segmentation and morphology assessment | NF-κB translocation quantification [16] |

| Gene Expression Analysis | RNAscope probes for JAK/STAT pathway genes, Luciferase reporter constructs [9] [14] | Measure transcriptional activity and gene expression changes | Detection of low-abundance transcripts [14], Reporter gene assays [9] |

Pathway Diagrams and Visualization

GPCR Signaling and Detection Methods

JAK/STAT Signaling Pathway

NF-κB Translocation Assay Workflow

MAPK Signaling in Liver Cancer Apoptosis

The comprehensive analysis of GPCR, MAPK, JAK/STAT, and NF-κB signaling pathways provides critical insights for targeted drug discovery. The experimental protocols and application notes presented here offer robust methodologies for investigating these pathways, enabling researchers to quantify pathway activity, screen therapeutic compounds, and elucidate mechanisms of action. As our understanding of signaling network complexity grows, continued refinement of these biochemical assays will accelerate the development of novel therapeutics for cancer, inflammatory diseases, and other conditions driven by signaling pathway dysregulation. The integration of advanced detection technologies with pathway-specific assays represents a powerful approach for advancing drug discovery in the precision medicine era.

Intracellular signaling pathways represent the fundamental communication networks that govern cellular life, translating extracellular stimuli into precise physiological responses. The deliberate targeting of these pathways by pharmacological agents stands as a cornerstone of modern therapeutics, enabling treatment of cancer, metabolic disorders, neurological conditions, and inflammatory diseases. The historical recognition that small, hydrophobic molecules like steroid hormones could traverse the plasma membrane and directly influence nuclear transcription factors marked the conceptual birth of intracellular signaling as a druggable space [18]. This paradigm has evolved dramatically, expanding from nuclear receptors to encompass G-protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs), kinase networks, and stem cell signaling pathways, with modern drug discovery increasingly focused on achieving unprecedented selectivity through structural biology and mechanistic understanding.

The clinical and commercial impact of targeting intracellular signaling is profound; approximately 30% of all FDA-approved medications target GPCRs alone [19], while drugs targeting nuclear receptors and protein kinases constitute another substantial segment of the pharmacopeia. Contemporary research has moved beyond simple receptor antagonism or agonism toward sophisticated manipulation of biased signaling, pathway selectivity, and allosteric modulation, allowing for finer control over therapeutic outcomes while minimizing adverse effects. This application note details the key historical milestones, current methodological approaches, and practical protocols that enable researchers to investigate and manipulate intracellular signaling pathways for therapeutic development, framed within the context of biochemical assays for intracellular signaling analysis research.

Historical Context and Key Discoveries

The conceptual foundation for targeting intracellular signaling was laid in the early 20th century with the discovery of hormones and their receptors. In 1905, Ernest Starling coined the term "hormone," establishing the principle of chemical messengers [18], while the subsequent isolation of estrogen by Adolf Butenandt and Edward Adelbert Doisy in 1929 provided the first tangible evidence that specific molecules could exert profound physiological effects [18]. The critical breakthrough came in the late 1950s through Elwood Jensen's experiments elucidating how estrogen regulates reproductive organ maturation, demonstrating that these hormones acted through specific intracellular receptors [18].

The molecular biology revolution of the 1980s accelerated this understanding dramatically. In 1985, Ronald Evans successfully cloned the human glucocorticoid receptor (GR) [18], while Pierre Chambon's laboratory identified the first estrogen receptor, ERα, from the ESR1 gene [18]. These discoveries revealed that steroid and thyroid hormone receptors shared evolutionary conservation with v-erbA, a viral oncogene recognized as a thyroid hormone receptor, leading to the formal establishment of the nuclear receptor superfamily [18]. This period marked the transition from physiological observation to molecular mechanism, revealing that many intracellular receptors functioned as ligand-activated transcription factors that directly bind DNA to modulate gene expression.

The therapeutic potential of targeting intracellular signaling was recognized in the 1970s when tamoxifen was shown to inhibit ER-dependent breast cancer cells [18]. This established the proof-of-concept that intracellular signaling pathways could be pharmacologically modulated for disease treatment, paving the way for countless subsequent therapies. The discovery and characterization of GPCRs as the largest family of membrane receptors further expanded the intracellular targeting landscape, with ongoing research continuing to reveal new dimensions of complexity, including receptor heterodimerization, intracellular allosteric sites, and biased signaling pathways that enable precise pharmacological control [19].

Table 1: Historical Milestones in Intracellular Signaling Research

| Year | Discovery | Key Researchers | Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1905 | Concept of "hormones" established | Ernest Starling | Foundation of endocrine signaling |

| 1929 | Isolation of estrogen | Butenandt & Doisy | First evidence of specific signaling molecules |

| Late 1950s | Estrogen receptor mechanism | Elwood Jensen | Demonstrated intracellular signaling pathways |

| 1985 | Cloning of glucocorticoid receptor | Ronald Evans | Molecular understanding of nuclear receptors |

| 1980s | Identification of ERα | Pierre Chambon | Established nuclear receptor superfamily |

| 1970s | Tamoxifen therapeutic mechanism | Multiple groups | Proof-of-concept for targeted intracellular therapy |

| 2010s-Present | Intracellular biased allosteric modulators | Multiple groups | Pathway-selective pharmacological manipulation |

Modern Targeting Strategies and Signaling Pathways

Nuclear Receptors as Pharmacological Targets

Nuclear receptors (NRs) represent one of the most therapeutically successful classes of intracellular targets. The human genome encodes 48 nuclear receptors that sense hydrophobic signaling molecules—including steroids, thyroid hormones, vitamin D, retinoic acid, and fatty acid derivatives—to directly modulate gene expression [18]. These receptors share a conserved modular structure containing a DNA-binding domain (DBD), ligand-binding domain (LBD), and transcription activation domains [18]. Upon ligand binding, NRs undergo conformational changes, form dimers, and bind to specific hormone response elements (HREs) in regulatory regions of target genes [18].

The clinical importance of NRs is exemplified by drugs like tamoxifen and raloxifene (estrogen receptor modulators for breast cancer and osteoporosis), enzalutamide (androgen receptor antagonist for prostate cancer), and thiazolidinediones (PPARγ agonists for type 2 diabetes) [18]. Current research focuses on developing agents with improved specificity to overcome the side effects associated with first-generation NR drugs, including severe heart failure observed with some PPARγ agonists [18]. The structural characterization of NR-ligand interactions has enabled rational drug design approaches to optimize binding affinity and functional selectivity.

G-Protein-Coupled Receptors (GPCRs) and Intracellular Modulation

GPCRs represent the largest family of cell surface receptors and the most successful target class for FDA-approved drugs [19]. Traditional drug discovery focused on orthosteric binding sites, but recent advances have revealed the therapeutic potential of intracellular allosteric modulators that offer superior subtype selectivity and pathway bias [19]. GPCR signaling complexity arises from their ability to couple to multiple intracellular transducer families—including Gαs, Gαi/o, Gαq/11, and Gα12/13 subunits—as well as β-arrestins, which can mediate both receptor desensitization and G protein-independent signaling [19].

The concept of biased signaling (or functional selectivity) has emerged as a pivotal strategy for intracellular pharmacological targeting [19]. Biased ligands stabilize distinct receptor conformations that preferentially activate beneficial signaling pathways while minimizing engagement of pathways responsible for adverse effects. For example, at the mu opioid receptor (MOR), G protein-biased agonists may provide analgesia without the β-arrestin-mediated effects associated with respiratory depression and constipation [20]. Recent structural biology breakthroughs, including cryo-electron microscopy studies, have identified novel intermediate receptor states (latent, engaged, unlatched, and primed) that provide unprecedented opportunities for designing precision therapeutics [20].

Stem Cell Signaling Pathways

The signaling networks that regulate stem cell fate—including Hedgehog, TGF-β, Wnt, Hippo, FGF, BMP, and Notch pathways—represent increasingly important pharmacological targets for regenerative medicine and cancer treatment [21]. These pathways collectively control stem cell self-renewal, differentiation, and migration, offering multiple intervention points for therapeutic manipulation [21]. Pharmacological modulation of these pathways enables enhancement of stem cell survival, directed differentiation, and suppression of tumorigenic potential in stem cell-based therapies [21].

The TGF-β pathway exemplifies both the promise and challenge of targeting developmental signaling pathways. This pathway plays crucial roles in tissue homeostasis, immune regulation, and stem cell maintenance [21]. TGF-β signaling occurs through SMAD-dependent (SMAD1/5/8 or SMAD2/3) and SMAD-independent (TAB/TAK) pathways, with context-dependent effects that can either suppress or promote disease progression [21]. This dual nature makes careful pharmacological modulation essential, particularly in applications involving stem cell fate control.

Protein Kinase Networks

Protein kinases represent one of the largest and most pharmacologically targeted enzyme families, regulating virtually all intracellular signaling processes through phosphorylation. As of 2025, numerous small molecule kinase inhibitors have received FDA approval for conditions ranging from cancer to inflammatory diseases [22]. These agents typically target the conserved ATP-binding pocket but achieve selectivity through unique interactions with adjacent regions. Modern kinase drug discovery emphasizes covalent inhibitors, allosteric modulators, and bivalent compounds that can overcome resistance mutations and improve therapeutic windows.

Experimental Approaches and Methodological Considerations

Biochemical vs. Cellular Assays: Bridging the Activity Gap

A fundamental challenge in targeting intracellular signaling is the frequent discrepancy between compound activity measured in biochemical assays (BcAs) and cellular assays (CBAs). These discrepancies often arise from differences in membrane permeability, intracellular compound stability, target specificity, and the distinct physicochemical environments between simplified in vitro conditions and the intracellular milieu [23].

The intracellular environment differs dramatically from standard biochemical assay conditions like phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). Intracellular conditions feature high macromolecular crowding (occupying 5–40% of total volume), viscosity approximately 4 times that of water, and reversed potassium-to-sodium ratio (K+ ~140–150 mM vs. Na+ ~14 mM) compared to extracellular-like buffers [23]. These differences can alter measured Kd values by up to 20-fold or more between biochemical and cellular contexts [23]. To address this, researchers are developing cytoplasm-mimicking assay buffers that incorporate crowding agents (e.g., Ficoll, dextrans), adjusted ionic composition, and viscosity modifiers to better predict cellular activity [23].

Table 2: Key Differences Between Standard Biochemical and Intracellular Conditions

| Parameter | Standard Biochemical Assay (e.g., PBS) | Intracellular Environment | Impact on Binding/Activity |

|---|---|---|---|

| K+ vs. Na+ Ratio | Low K+ (4.5 mM), High Na+ (157 mM) | High K+ (140-150 mM), Low Na+ (~14 mM) | Alters electrostatic interactions & binding |

| Macromolecular Crowding | Minimal | 5-40% of volume occupied | Enhances binding affinity through excluded volume effect |

| Viscosity | ~1 cP (similar to water) | ~4 cP | Slows diffusion & affects binding kinetics |

| pH | Generally 7.4 | Variable by compartment | Affects ionization & hydrogen bonding |

| Redox Potential | Oxidizing | Reducing (high glutathione) | Affects disulfide-dependent proteins |

Quantifying Intracellular Drug Exposure and Activity

Understanding the relationship between extracellular concentration and intracellular target engagement is crucial for developing drugs against intracellular targets. The growth rate inhibition (GR) method provides a robust framework for quantifying cellular drug sensitivity by normalizing response to cell division rate, generating metrics such as GR50 (concentration producing half-maximal growth inhibition) and GRmax (maximal response) [24]. This approach minimizes confounding effects from variable cell division rates that plague traditional IC50 measurements [24].

Complementing GR analysis, liquid chromatography tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) enables direct quantification of intracellular drug concentrations, bridging the gap between nominal dosing and actual target exposure [24]. This is particularly important for compounds like the auristatins (MMAE and MMAD), which exhibit differential cellular accumulation due to variations in passive permeability, efflux transporter activity, and intracellular binding [24]. For example, MMAD shows higher lipophilicity (eLogD 4.43 vs. 3.99 for MMAE) and greater susceptibility to MDR1 and BCRP efflux pumps, significantly impacting its intracellular concentration despite similar passive permeability [24].

Application Notes and Protocols

Protocol: Growth Rate Inhibition (GR) Assay for Cellular Sensitivity

Purpose: To robustly quantify cellular sensitivity to pharmacological compounds by normalizing response to cell division rate.

Materials:

- Cell lines of interest (e.g., MDA-MB-468, HCC1806 for triple-negative breast cancer)

- Compound(s) of interest (e.g., MMAE, MMAD as tool microtubule inhibitors)

- Cell culture medium and supplements

- CellTiter-Glo (CTG) viability assay kit

- White opaque tissue culture-treated assay plates

- Plate reader capable of measuring luminescence

Procedure:

- Cell Seeding: Seed cells in exponential growth phase at optimal density (typically 500-5000 cells/well depending on doubling time) in 100 μL medium per well. Include background control wells (medium only) and vehicle control wells (DMSO equivalent to highest compound concentration).

- Compound Treatment: After 24-hour incubation, add compound in serial dilutions (typically 3- or 10-fold), maintaining constant DMSO concentration across all wells (≤0.1%).

- Endpoint Viability Measurement: Following 72-hour compound exposure, equilibrate plates to room temperature for 30 minutes. Add CellTiter-Glo reagent (1:1 volume to medium), mix for 2 minutes, incubate for 10 minutes to stabilize signal, and measure luminescence.

- GR Calculation:

- Calculate normalized growth rate inhibition using the GR calculator (available at GRcalculator.org)

- Apply the formula: GR(c) = 2^(log2(x(c)/x0)/log2(x1/x0)) - 1, where x(c) = measured viability at concentration c, x0 = viability at time of compound addition, x1 = viability of untreated cells at endpoint

- Derive GR50 (concentration where GR = 0.5) and GRmax (maximal effect) values from the GR curve

Troubleshooting:

- If GR curves show poor fit, verify cell doubling time during assay and adjust seeding density

- If high variability between replicates, ensure consistent cell counting and mixing before seeding

- If signal-to-background ratio is low, optimize cell seeding density or extend treatment duration

Protocol: In-Cell Biochemical Binding Assessment

Purpose: To measure protein-ligand binding affinity under conditions mimicking the intracellular environment.

Materials:

- Purified target protein

- Test compounds

- Cytoplasm-mimicking buffer (20 mM HEPES, pH 7.4, 140 mM KCl, 14 mM NaCl, 5 mM MgCl2, 1 mM DTT, 20% Ficoll PM-70)

- Standard assay buffer (e.g., PBS for comparison)

- Binding assay reagents (e.g., fluorescence polarization tracers, SPR chips)

Procedure:

- Buffer Preparation: Prepare cytoplasm-mimicking buffer with crowding agent (Ficoll PM-70 at 20% w/v) and adjusted ionic composition to match intracellular conditions.

- Binding Reaction Setup: Dilute purified target protein in both cytoplasm-mimicking and standard buffers. Incubate with compound serial dilutions using assay-appropriate format (96- or 384-well plate).

- Equilibrium Measurement: For fluorescence polarization, incubate with tracer ligand and measure polarization after equilibrium (typically 30-60 minutes at 25°C). For SPR, immobilize target and measure compound binding in both buffer systems.

- Kd Calculation: Fit binding data to appropriate model (e.g., one-site binding) to determine Kd values in both buffer systems.

- Data Interpretation: Compare Kd values between standard and cytoplasm-mimicking conditions. A significant difference (>3-fold) suggests intracellular environment impacts binding affinity.

Notes:

- Include controls for non-specific binding in both buffer systems

- For membrane protein targets, incorporate lipid vesicles at physiologically relevant composition

- Consider temperature dependence (25°C vs. 37°C) for physiologically relevant measurements

Protocol: Intracellular Drug Concentration Measurement by LC-MS/MS

Purpose: To quantitatively determine intracellular drug concentrations correlating with pharmacological activity.

Materials:

- Treated cell cultures

- LC-MS/MS system with appropriate analytical column

- Internal standard (stable isotope-labeled analog of analyte)

- Solvents: methanol, acetonitrile, water (LC-MS grade)

- Formic acid (LC-MS grade)

Procedure:

- Sample Preparation: After compound treatment, wash cells twice with cold PBS. Lyse cells with 80:20 methanol:water containing internal standard. Vortex vigorously and centrifuge at 15,000 × g for 10 minutes.

- Sample Analysis: Inject supernatant onto LC-MS/MS system. Use appropriate mobile phase gradient (typically water and methanol/acetonitrile with 0.1% formic acid) and MRM transitions for compound quantification.

- Normalization: Determine protein concentration in pellet using BCA assay or count cells in parallel wells for normalization.

- Data Analysis: Calculate intracellular concentration using standard curve with internal standard normalization. Express as pmol/mg protein or pmol/million cells.

Validation:

- Determine extraction efficiency by comparing spiked samples before and after extraction

- Establish linear range and lower limit of quantification using matrix-matched standards

- Assess matrix effects by post-extraction spiking experiments

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Research Reagents for Intracellular Signaling Analysis

| Reagent/Category | Example Products | Research Application | Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cytoplasm-Mimicking Buffers | Custom formulations with Ficoll, dextrans | Biochemical assays under intracellular-like conditions | Significantly impacts measured Kd values; improves translatability |

| GR Metrics Software | GR Calculator (online) | Robust quantification of cellular drug sensitivity | Normalizes for cell division rate; more reliable than traditional IC50 |

| LC-MS/MS Systems | Various commercial platforms | Direct measurement of intracellular drug concentrations | Bridges extracellular dosing and intracellular target engagement |

| Spectral Flow Cytometry | 39-color panels | High-dimensional immune profiling in minimal samples | Enables identification of 60+ immune subsets from small biopsies |

| Intracellular Biased Modulators | Carvedilol (β-arrestin-biased β-blocker) | Pathway-selective GPCR modulation | Demonstrates therapeutic potential of biased signaling |

| Crowding Agents | Ficoll PM-70, dextran | Mimicking intracellular macromolecular crowding | Excluded volume effect enhances binding affinity |

| Cryo-EM Platforms | Various commercial systems | Structural biology of receptor-ligand complexes | Enabled discovery of novel GPCR states (latent, engaged, unlatched, primed) |

Signaling Pathway Visualizations

Diagram 1: GPCR Intracellular Signaling Pathways. Ligand binding to GPCRs initiates multiple intracellular signaling cascades, including G-protein-dependent pathways (green) and β-arrestin-mediated pathways (red), demonstrating the complexity enabling biased agonism.

Diagram 2: Nuclear Receptor Signaling Mechanism. Small hydrophobic ligands traverse the plasma membrane to bind intracellular nuclear receptors, which translocate to the nucleus, dimerize, bind hormone response elements (HREs), and recruit co-regulators to modulate gene expression.

Diagram 3: Integrated Workflow for Intracellular Target Validation. Comprehensive approach combining functional cellular response (GR metrics), intracellular exposure quantification, and target engagement assessment under physiologically relevant conditions.

The targeted modulation of intracellular signaling pathways continues to evolve from broad receptor antagonism toward exquisitely precise manipulation of specific signaling nodes and conformational states. The integration of advanced structural biology techniques like cryo-EM, which recently revealed four previously unknown conformational states of the mu opioid receptor [20], with sophisticated cellular pharmacology approaches such as GR analysis and intracellular exposure measurement, provides an unprecedented toolkit for rational drug design. The deliberate recreation of intracellular physicochemical conditions in biochemical assays further bridges the gap between simplified in vitro systems and complex cellular environments, enhancing the predictive power of early discovery assays [23].

Future directions in intracellular signaling pharmacology will likely emphasize tissue-specific pathway modulation, combination therapies targeting complementary nodes within signaling networks, and patient-specific approaches informed by genomic and proteomic profiling. The continued development of research tools that more accurately recapitulate the intracellular environment—coupled with advanced analytics for quantifying target engagement in physiologically relevant contexts—will accelerate the development of safer, more effective therapeutics that precisely manipulate intracellular signaling for diverse therapeutic applications.

Application Note: Unraveling Wnt/β-catenin Pathway Crosstalk in Colorectal Cancer

In colorectal cancer (CRC), intricate cross-talk between dysregulated microRNAs (miRNAs) and the Wnt signaling pathway plays a pivotal role in cancer initiation and progression [25]. Systems biology approaches reveal that this miRNA-Wnt crosstalk represents a critical regulatory layer, offering promising avenues for innovative therapeutic strategies. Network analysis of these interactions has identified key hub proteins that serve as central regulators within the signaling network, making them potential high-value targets for intervention [25].

Key Findings from Network Analysis

A comprehensive systems biology study compiling genes influenced by dysregulated miRNAs targeting the Wnt pathway identified 15 central hub proteins through protein-protein interaction (PPI) network analysis [25]. These hubs represent critical nodes where multiple signaling pathways converge and cross-talk occurs.

Table 1: Central Hub Proteins in Wnt-miRNA Crosstalk Network

| Hub Protein | Functional Category | Role in Signaling Network |

|---|---|---|

| EP300 | Transcriptional coactivator | Chromatin modification, signal integration |

| NRAS | GTPase | Proliferative signaling |

| NF1 | GTPase activating protein | Ras pathway regulation |

| CCND1 | Cyclin | Cell cycle progression |

| SMAD4 | Transcription factor | TGF-β signaling pathway |

| SOCS7 | Suppressor of cytokine signaling | Cytokine signaling regulation |

| SOCS6 | Suppressor of cytokine signaling | Cytokine signaling regulation |

| NECAP1 | Adaptor protein | Clathrin-mediated endocytosis |

| MBTD1 | Chromatin reader | Transcriptional regulation |

| ACVR1C | Receptor serine/threonine kinase | TGF-β superfamily signaling |

| ESR1 | Nuclear hormone receptor | Estrogen signaling |

| CREBBP | Transcriptional coactivator | Histone acetyltransferase |

| PIK3CA | Lipid kinase | PI3K-AKT signaling |

Gene ontology and KEGG enrichment analysis revealed these hub proteins participate in critical biological processes, cellular components, and molecular functions, with significant enrichment in cancer-related pathways [25]. CytoCluster analysis further identified dysregulated miRNA-targeted gene clusters linked to these pathways, while promoter motif analysis provided insights into regulatory elements governing hub protein expression.

Protocol: Multiplex Analysis of Intracellular Signaling Pathways

This protocol describes a multiplex microbead suspension array approach for simultaneous phosphoproteomic profiling of multiple signaling proteins in lymphoid cells, enabling comprehensive analysis of signaling pathway cross-talk and kinetics from membrane-proximal events to nuclear transcription factors [26].

Materials and Reagents

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions for Multiplex Signaling Analysis

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Function/Application |

|---|---|---|

| Phospho-specific Antibodies | Anti-pCD3, Anti-pLck, Anti-pZap-70, Anti-pErk, Anti-pAkt, Anti-pSTAT3 | Target-specific detection of phosphorylation events |

| Microbead Suspension Array | Luminex-based beadsets | Multiplex analyte detection platform |

| Cell Lysis Buffer | Modified RIPA with phosphatase/protease inhibitors | Protein extraction while preserving phosphorylation |

| Detection Reagents | Phycoerythrin-conjugated secondary antibodies | Signal amplification and detection |

| Validation Tools | Western blot, Immunoprecipitation reagents | Method validation and confirmation |

Experimental Workflow

Detailed Methodology

Cell Stimulation and Protein Extraction

- Culture Jurkat T-cells or B-cell chronic lymphocytic leukemia lines in appropriate medium

- Stimulate cells with relevant activators for varying durations (0-60 minutes) to capture signaling kinetics

- Lyse cells in ice-cold lysis buffer containing phosphatase and protease inhibitors

- Clarify lysates by centrifugation at 14,000 × g for 15 minutes at 4°C

- Quantify protein concentration using standardized assay (e.g., BCA assay)

Multiplex Bead Assay

- Incubate 50 μg of total protein with antibody-coupled microbead mixture for 2 hours at room temperature with gentle shaking

- Wash beads twice with wash buffer to remove unbound protein

- Incubate with phospho-specific detection antibodies for 1 hour

- Add phycoerythrin-conjugated secondary antibody for 30 minutes

- Analyze using suspension array reader with manufacturer-recommended settings

Data Analysis and Validation

- Normalize fluorescence intensities to internal controls

- Generate kinetic profiles for each phosphoprotein across time points

- Validate key findings using traditional immunoprecipitation and Western blot methods [26]

- Perform statistical analysis to determine significant phosphorylation changes

Protocol: Systems Biology Workflow for Network Analysis of Signaling Pathways

This protocol outlines a multi-layered systems biology framework for identifying key regulatory genes and proteins in complex signaling networks, adapted from successful applications in cancer and plant stress biology research [25] [27].

Computational Materials and Tools

Table 3: Computational Tools for Systems Biology Analysis

| Tool Category | Specific Tools | Application Purpose |

|---|---|---|

| Network Analysis | Cytoscape with StringApp 2.0 | PPI network construction and visualization |

| Enrichment Analysis | ClusterProfiler, Enrichr | Gene ontology and pathway enrichment |

| Topology Analysis | CytoHubba, NetworkAnalyzer | Hub protein identification |

| Data Integration | Custom R/Python scripts | Multi-omics data integration |

Systems Biology Workflow

Detailed Computational Methods

Data Integration and Candidate Gene Selection

- Compile initial gene/protein list from relevant omics datasets (transcriptomics, proteomics)

- For CRC Wnt signaling example: compile genes influenced by dysregulated miRNAs targeting Wnt pathway [25]

- Utilize miRDB database for high-scoring miRNA-target interactions

- Apply statistical corrections (e.g., FOSCO method) to address gene size bias when working with SNP data [27]

Network Construction and Analysis

- Import candidate genes into Cytoscape and construct PPI networks using StringApp 2.0

- Apply multiple algorithms (MCC, MNC, DMNC, and Degree) for robust hub protein identification

- Calculate network topology parameters (betweenness centrality, closeness centrality)

- Identify network clusters and modules using CytoCluster algorithms

Functional Enrichment and Validation

- Perform gene ontology analysis for biological process, cellular component, and molecular function

- Conduct KEGG pathway enrichment to identify significantly represented pathways

- Execute promoter motif analysis to identify regulatory elements

- Validate computational predictions through experimental approaches (qPCR, functional assays)

Protocol: Advanced Network Visualization in Cytoscape

Visualization Setup for Signaling Networks

Effective visualization is crucial for interpreting complex signaling networks and their cross-talk. This protocol details advanced Cytoscape techniques for highlighting hub proteins and pathway interactions [28].

Visualization Workflow

Detailed Visualization Steps

Style Configuration for Hub Proteins

- Create a new style in Cytoscape Style interface

- Map node size to network degree or betweenness centrality to highlight hubs:

- Go to Properties → Size → Size and select Column mapping

- Choose degree column and set size range (20-100 for clear visualization)

- Map node color to functional category or pathway association:

- Select Properties → Fill Color and choose Discrete mapping

- Assign distinct colors to different functional categories

- Map node shape to protein type (receptor, kinase, transcription factor)

Edge and Pathway Visualization

- Map edge line type to interaction type (protein-protein, protein-DNA)

- Set edge width proportional to interaction confidence score

- Use curved edges for improved visualization of dense networks

- Apply edge opacity settings to reduce visual clutter in dense networks

Advanced Layout and Color Schemes

- Apply force-directed layout algorithms to emphasize network structure

- Use hierarchical layout for signaling cascades

- Implement sequential color palettes for gradient data (expression levels)

- Use divergent color palettes for positive/negative regulation data

- Apply qualitative color palettes for discrete categorical data [29]

Data Integration and Interpretation

Quantitative Data Analysis Framework

Systems biology approaches generate multiple quantitative datasets that require standardized summarization and interpretation frameworks [30] [31].

Statistical Analysis and Data Representation

- Generate frequency distributions for node degrees, interaction counts, and expression values

- Create histogram visualizations to understand distribution patterns of network parameters

- Calculate relative frequencies for pathway representation analyses

- Perform comparative analysis between different signaling conditions or time points

Table 4: Quantitative Data Analysis Methods for Signaling Networks

| Data Type | Analysis Method | Visualization Approach |

|---|---|---|

| Node Degree Distribution | Frequency table, histogram | Power-law distribution plot |

| Pathway Enrichment | Hypergeometric test, FDR correction | Bar chart, bubble plot |

| Expression Profiles | Relative frequency, z-score normalization | Heat map, line graph |

| Kinetic Phosphorylation | Time-series analysis | Frequency polygon, multi-line chart |

The integration of multiplex experimental approaches with computational systems biology creates a powerful framework for unraveling the complexity of signaling networks, identifying critical hub proteins, and understanding pathway cross-talk in disease and therapeutic contexts. These protocols provide researchers with comprehensive methodologies to advance signaling network research from isolated pathway analysis to integrated network perspectives.

A Practical Guide to Biochemical Assay Technologies for Signaling Analysis

G protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs) represent a paramount family of cell surface receptors and are critical targets in modern drug discovery. Their activation triggers intracellular signaling cascades mediated by key second messengers, including cyclic AMP (cAMP), calcium ions (Ca²⁺), and inositol trisphosphate (IP3), which is indirectly measured via its downstream metabolite, inositol monophosphate (IP1). Accurate quantification of these second messengers is therefore fundamental to understanding receptor function, screening for novel therapeutics, and deciphering complex cellular communication networks [32] [33].

This application note provides a consolidated resource for researchers and drug development professionals, detailing the principles, protocols, and quantitative data for three essential assays. The content is framed within a broader research context focused on biochemical assays for intracellular signaling analysis, emphasizing the practical aspects of assay selection, optimization, and data interpretation to ensure reliable and physiologically relevant results.

Second Messenger Pathways and Assay Principles

Signaling Pathways and Detection Logic

The following diagrams illustrate the core signaling pathways and the fundamental principles behind the assays used to quantify each second messenger.

Diagram 1: Second Messenger Signaling and Detection. This figure outlines the primary GPCR signaling pathways. Activation of Gαs or Gαi proteins regulates cAMP production by adenylyl cyclase (AC), while Gαq activation triggers phospholipase C (PLC), which cleaves PIP₂ into DAG and IP₃. IP₃ releases Ca²⁺ from intracellular stores, and is rapidly metabolized to IP1. Dashed lines indicate the specific molecular species measured by each assay [32] [33] [34].

Core Assay Methodologies

The following diagram provides a high-level overview of the experimental workflow common to these second messenger assays, highlighting key steps from cell preparation to data analysis.

Diagram 2: Generic Experimental Workflow. This flowchart summarizes the core steps for performing cAMP, IP1, and Ca²⁺ mobilization assays. Key optimization points include cell density, stimulation time, and compatibility with antagonist/inverse agonist studies [33] [35] [34].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Selecting the appropriate reagents and tools is critical for successful assay execution. The following table catalogs key solutions used in the featured experiments.

Table 1: Essential Research Reagents and Kits for Second Messenger Assays

| Item Name | Function/Description | Example Assay Context |

|---|---|---|

| cAMP-Glo Assay [36] | Bioluminescent assay measuring cAMP via protein kinase A (PKA)-coupled luciferase reaction. | Homogeneous, high-throughput screening for Gαs- and Gαi-coupled GPCR activity. |

| HTRF cAMP Kit [33] | Competitive immunoassay using Eu³⁺-cryptate labeled antibody and d2-labeled cAMP; TR-FRET readout. | Gold-standard for cAMP quantification in Gαs/Gαi studies; used with suspension or adherent cells. |

| FLIPR Calcium 4/5 Assay Kit [37] [35] | No-wash fluorescent dye kit for detecting intracellular calcium flux. | Real-time kinetic measurements of Ca²⁺ mobilization in Gq-coupled receptor activation on FLIPR/FlexStation. |

| Fluo-4 AM / Fura-2 AM [32] | Cell-permeant, calcium-sensitive fluorescent dyes for live-cell imaging and fluorometry. | Flexible calcium mobilization assays adaptable to various plate readers and imaging systems. |

| IP-One HTRF Kit [38] [34] | Competitive immunoassay quantifying accumulated IP1, a stable downstream metabolite of IP3. | Robust and homogeneous assay for Gαq-coupled receptor activity; measures IP1 accumulation in cell lysates. |

| HTplex Assay [34] | Multiplexed HTRF assay allowing simultaneous measurement of cAMP and IP1 from a single well. | Investigating biased agonism or receptor cross-talk between Gαi/s and Gαq pathways. |

Comparative Analysis of Key Assay Parameters

A critical step in experimental design is selecting the assay most appropriate for the biological question and logistical constraints. The following table provides a direct comparison of the core quantitative and operational parameters for the three second messenger assays.

Table 2: Quantitative and Operational Comparison of Second Messenger Assays

| Parameter | cAMP Assay (e.g., HTRF) [33] [34] | Ca²⁺ Mobilization Assay [32] [37] [35] | IP1 Assay (e.g., HTRF) [38] [34] |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary GPCR Coupling | Gαs (increase), Gαi (decrease) | Gαq, Gαi (via βγ subunits) | Gαq |

| Key Measured Analyte | Intracellular cAMP | Free cytosolic Ca²⁺ | Intracellular IP1 |

| Detection Technology | Competitive TR-FRET immunoassay | Fluorescent intensity (Fluo-4, Fura-2) | Competitive TR-FRET immunoassay |

| Assay Readout | Ratiometric (Em665/Em620) | Fluorescence units (RFU) | Ratiometric (Em665/Em620) |

| Assay Format | Endpoint (cell lysis) | Real-time kinetic | Endpoint (cell lysis) |

| Detection Range | ~0.1 - 10,000 nM (cAMP) | N/A (kinetic trace) | ~1 - 10,000 nM (IP1) |

| Temporal Resolution | Single time point (e.g., 30 min - 1 hr) | High (seconds) | Single time point (e.g., 1 hr) |

| Constitutive Activity Detection | Yes [32] | No [32] | Yes [32] |

| Advantages | Highly sensitive, robust HTS, direct quantification, multiplexable | Fast, highly dynamic, provides kinetic profile | Highly robust HTS, insensitive to receptor internalization, direct quantification |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol: cAMP Assay for Gαs-Coupled Receptors using HTRF

This protocol utilizes the Cisbio HTRF cAMP kit to measure agonist-induced cAMP production in cells expressing a Gαs-coupled GPCR [33].

Materials:

- Cells expressing the target GPCR (e.g., HEK293 or CHO cells)

- HTRF cAMP assay kit (Cisbio)

- Assay Buffer: 1X HBSS with 20 mM HEPES, 0.1% BSA (fatty acid-free)

- Forskolin (for Gαi-coupled receptor assays)

- Reference agonist and test compounds

- 384-well low-volume, white microplate

Procedure:

- Cell Preparation: Harvest cells in log growth phase. Centrifuge at 1000 rpm for 5 minutes, aspirate medium, and resuspend in assay buffer. Count and dilute cells to an optimized density (e.g., 0.5-1 million cells/mL). Dispense 20 µL of cell suspension into each well of a 384-well assay plate.

- Compound Addition: Prepare a 5X concentration of the agonist or test compound in assay buffer. Add 5 µL of the 5X compound solution to the cell suspension, resulting in a final 1X concentration and a total assay volume of 25 µL. Incubate the plate for 30 minutes at room temperature.

- Detection Reagent Addition: During the incubation, prepare the HTRF detection solution by reconstituting the lyophilized cAMP-d2 (acceptor) and Anti-cAMP-Eu³⁺ Cryptate (donor) according to the kit instructions. Add 5 µL of the detection solution to each well.

- Incubation and Reading: Incubate the plate for 1 hour at room temperature protected from light. Read the plate on a compatible microplate reader (e.g., BMG LABTECH PHERAstar) equipped with HTRF optics. Settings include: excitation at 337 nm, dual-emission detection at 620 nm (donor) and 665 nm (acceptor) after a 50-150 µs delay.

- Data Analysis: Calculate the fluorescence ratio for each well: (Emission at 665 nm / Emission at 620 nm) × 10⁴. Convert the ratio to cAMP concentration by interpolating from a cAMP standard curve run on the same plate. Plot agonist concentration-response curves to determine EC₅₀ values.

Notes: For Gαi-coupled receptors, cells must be co-stimulated with a concentration of forskolin (e.g., EC₅₀-EC₈₀) to elevate cAMP levels to a detectable range, upon which receptor activation will cause a decrease in the HTRF signal [33]. It is critical to use the standard curve for data conversion, as using raw signal ratios can lead to significant errors in potency estimation [33].

Protocol: Calcium Mobilization Assay using FLIPR Calcium 5 Dye

This protocol describes a robust method for measuring real-time intracellular calcium flux in response to Gq-coupled GPCR activation, optimized for a FlexStation microplate reader [35].

Materials:

- Cells expressing the target GPCR (e.g., HEK293-AT1R)

- FLIPR Calcium 5 Assay Kit (Molecular Devices)

- Poly-L-lysine (for cell adhesion)

- Probenecid (optional, to inhibit dye extrusion)

- Assay Buffer: 1X PBS or HBSS

- 96-well black-walled, clear-bottom assay plate

Procedure:

- Plate Preparation: Coat a 96-well assay plate with 0.01% poly-L-lysine (50 µL/well) for 30 minutes at 37°C. Remove the solution and wash wells once with PBS.

- Cell Seeding: Seed cells at an optimized density (e.g., 50,000 cells/well in 50 µL growth medium) to achieve 90-100% confluency at assay. Incubate overnight at 37°C, 5% CO₂.

- Serum Starvation: Aspirate the growth medium and add 100 µL of serum-free medium. Incubate for 2 hours at 37°C.

- Dye Loading: Prepare the FLIPR Calcium 5 dye loading solution according to the manufacturer's instructions. Add an equal volume (100 µL) of the dye solution directly to the serum-free medium in each well (do not aspirate). Incubate for 1 hour at 37°C, 5% CO₂, followed by 30 minutes at room temperature.

- Instrument Setup: Place the assay plate in the FlexStation. Prepare a ligand plate with agonists at 5X final concentration in a clear U-bottom plate. Configure the SoftMax Pro software with the following parameters: