Beyond the Symptom Checklist: Neurobiological Validation of Next-Generation Addiction Assessment Instruments

This article synthesizes current advancements in the neurobiological validation of addiction assessment tools, charting a paradigm shift from purely behavioral checklists to mechanistically informed instruments.

Beyond the Symptom Checklist: Neurobiological Validation of Next-Generation Addiction Assessment Instruments

Abstract

This article synthesizes current advancements in the neurobiological validation of addiction assessment tools, charting a paradigm shift from purely behavioral checklists to mechanistically informed instruments. We explore the foundational neuroscience of addiction, highlighting frameworks like the Addictions Neuroclinical Assessment (ANA) that link core neurofunctional domains—executive function, incentive salience, and negative emotionality—to specific stages of the addiction cycle. The review details innovative methodological approaches, including gamified digital neurocognitive batteries, AI-driven predictive analytics, and integrated genetic-behavioral tools. We address key challenges in implementation and optimization, such as clinical heterogeneity and tool feasibility. Finally, we present a comparative analysis of validation evidence, underscoring how these neurobiologically-grounded instruments enhance predictive validity, enable personalized risk detection, and inform the development of targeted therapeutics for researchers and drug development professionals.

The Brain on Addiction: Foundational Neurocircuitry and the Case for a New Assessment Paradigm

Addiction is now understood as a chronic brain disorder, characterized by clinically significant impairments in health, social function, and voluntary control over substance use [1]. This represents a fundamental shift from historical views of addiction as a moral failing or character flaw. Research accumulated over several decades has revealed that addictive substances produce profound changes in brain structure and function that promote and sustain the condition [1]. The neurobiological understanding of addiction has opened new avenues for prevention and treatment, with a particular focus on three key brain regions: the basal ganglia, extended amygdala, and prefrontal cortex [1] [2].

This review adopts a comparative approach to examine the neurocircuitry of addiction through the lens of the Addictions Neuroclinical Assessment (ANA), a neuroscience-based framework designed to address the substantial heterogeneity observed among individuals diagnosed with the same substance use disorder [3] [4]. By deconstructing the addiction cycle into its constituent neurofunctional domains and their underlying neural substrates, we provide researchers and drug development professionals with a structured analysis of assessment methodologies, their experimental validation, and the standardized research tools available for investigating this complex disorder.

The Three-Stage Addiction Cycle: Core Neurocircuitry and Functions

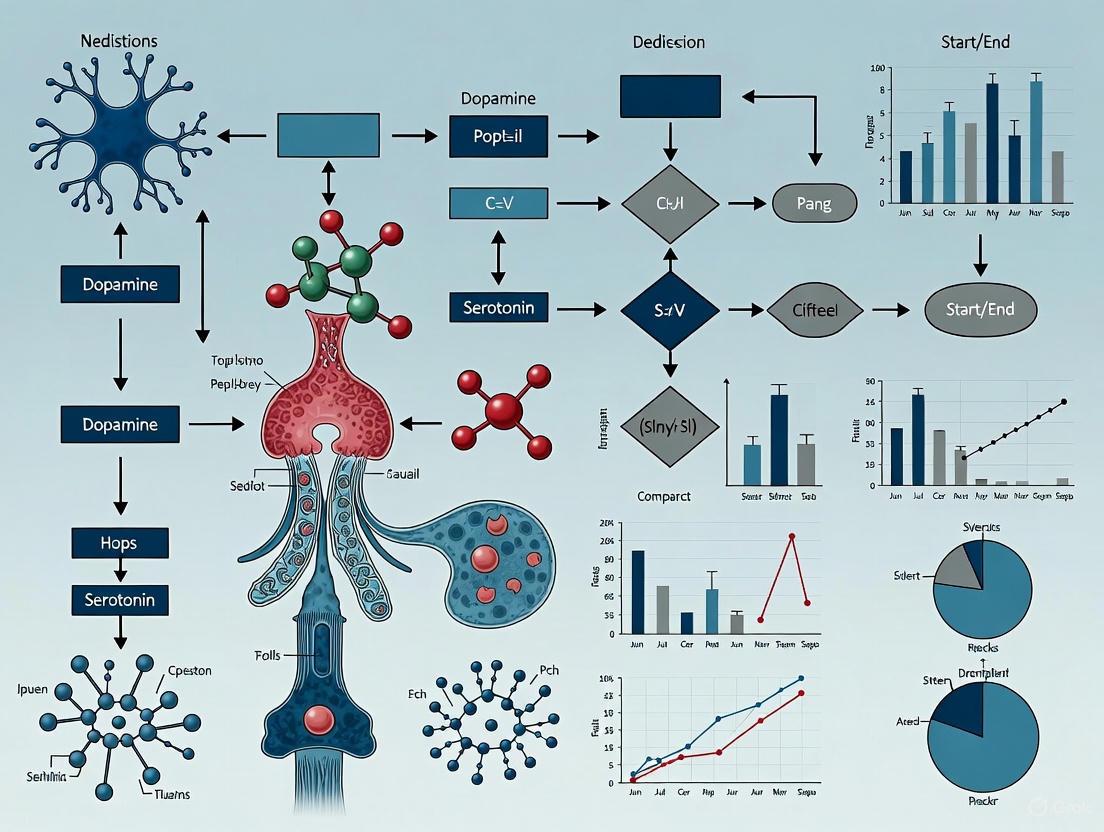

The addiction process is characterized by a three-stage cycle: binge/intoxication, withdrawal/negative affect, and preoccupation/anticipation. This cycle becomes more severe with continued substance use, producing dramatic changes in brain function that reduce an individual's ability to control their substance use [1]. Each stage is mediated by specific brain regions and circuits, which are detailed below and visualized in Figure 1.

Binge/Intoxication Stage: Basal Ganglia

The binge/intoxication stage is primarily centered on the basal ganglia and its role in reward processing [1] [5]. Key structures within the basal ganglia, particularly the nucleus accumbens, are responsible for the acute rewarding or pleasurable effects of substance use [1] [2]. When drugs are taken, they can produce surges of neurotransmitters such as dopamine and the brain's natural opioids (endorphins) in the reward circuit, which are significantly greater than those produced by natural, healthy rewards [2]. These neurochemical surges powerfully reinforce the connection between drug consumption, pleasure, and associated environmental cues, teaching the brain to seek drugs at the expense of other goals [2].

Withdrawal/Negative Affect Stage: Extended Amygdala

The withdrawal/negative affect stage is dominated by the extended amygdala [1] [5]. This region plays a key role in stress responses and is responsible for the feelings of unease, anxiety, irritability, and physical discomfort that characterize withdrawal after the drug high subsides [5] [2]. With repeated drug use, this circuit becomes increasingly sensitive. Over time, the individual may use substances primarily to gain temporary relief from this aversive state rather than to achieve pleasure [2]. This represents a critical shift in the motivation for drug use.

Preoccupation/Anticipation Stage: Prefrontal Cortex

The preoccupation/anticipation stage, which drives relapse, is heavily influenced by the prefrontal cortex (PFC) [1] [5]. The PFC is essential for executive function, including the ability to organize thoughts and activities, prioritize tasks, manage time, make decisions, and exert self-control over impulses [1] [2]. In addiction, the function of the PFC is disrupted. This leads to reduced impulse control and a diminished ability to make rational decisions about drug-seeking, even after periods of abstinence [2]. The shifting balance between the PFC (executive control) and the circuits of the basal ganglia and extended amygdala (reward and stress) underlies the compulsive drug seeking that marks addiction [5].

Figure 1. The Three-Stage Cycle of Addiction and Associated Brain Regions. This diagram illustrates the recurrent cycle of addiction, highlighting the primary brain regions and key neurobiological processes involved in each stage. The cycle is driven by progressive neuroadaptations in the basal ganglia, extended amygdala, and prefrontal cortex [1] [5].

Comparative Analysis of Assessment Frameworks and Instruments

A significant challenge in addiction research is the clinical heterogeneity among patients, which has prompted the development of neuroscience-based assessment frameworks that move beyond traditional symptom-based diagnoses [3] [4]. This section compares the dominant framework, the Addictions Neuroclinical Assessment (ANA), with the broader Research Domain Criteria (RDoC) initiative.

The Addictions Neuroclinical Assessment (ANA) Framework

The ANA is a heuristic framework that incorporates three key neurofunctional domains derived from the neurocircuitry of addiction [3]. It was proposed specifically to address the limitations of existing diagnostic systems and to differentiate patients based on etiology, prognosis, and treatment response [3]. The three core domains are:

- Incentive Salience (IS): This domain encompasses processes involved in reward, motivational salience, and habit formation, tied to the binge/intoxication stage of the addiction cycle [3] [4]. It is primarily associated with the basal ganglia.

- Negative Emotionality (NE): This domain captures negative affective states resulting from withdrawal and long-term drug use, corresponding to the withdrawal/negative affect stage [3] [4]. It is linked to the extended amygdala.

- Executive Function (EF): This domain comprises cognitive functions such as inhibitory control, decision-making, and planning, which are relevant to the preoccupation/anticipation stage and relapse [3] [4]. It is primarily governed by the prefrontal cortex.

A recent validation study (N=300) using a standardized ANA battery identified subfactors within these domains, revealing a more complex structure [4]. The findings, including the psychometric properties of the assessments, are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1: ANA Domain Factors and Assessment Metrics from a Standardized Battery Study (N=300) [4]

| ANA Domain | Identified Subfactors | Key Assessment Instruments/Tasks | Critical Findings |

|---|---|---|---|

| Incentive Salience | 1. Alcohol Motivation2. Alcohol Insensitivity | Alcohol Cue-Reactivity Task, Monetary Choice Questionnaire, Self-Report | Alcohol Motivation and Insensitivity showed the strongest ability to classify individuals with problematic drinking and AUD. |

| Negative Emotionality | 1. Internalizing2. Externalizing3. Psychological Strength | State-Trait Anxiety Inventory, Positive and Negative Affect Schedule, Self-Report | Internalizing (e.g., anxiety) was strongly correlated with factors from other domains, like Alcohol Motivation. |

| Executive Function | 1. Inhibitory Control2. Working Memory3. Rumination4. Interoception5. Impulsivity | Stop-Signal Task, Digit Span Task, Delay Discounting Task, Self-Report | Impulsivity was a key factor in classifying AUD status and was strongly correlated with Alcohol Motivation. |

Comparative Framework: Research Domain Criteria (RDoC)

The RDoC is a broader framework initiated by the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) to create a research structure for studying all psychiatric diseases based on dimensions of observable behavior and neurobiological measures [3]. While not specific to addiction, the ANA domains align closely with the following RDoC constructs:

- Positive Valence Systems (similar to Incentive Salience)

- Negative Valence Systems (similar to Negative Emotionality)

- Cognitive Systems (similar to Executive Function) [3] [4]

The primary distinction is that ANA is a more focused framework specifically tailored to the neurobiology of addictive disorders and designed for clinical assessment, whereas RDoC provides a larger, transdiagnostic research matrix [3].

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies in Preclinical Research

To support the translation of neurobiological findings into treatments, standardized preclinical testing protocols are essential. The National Institute on Drug Abuse's (NIDA) Addiction Treatment Discovery Program (ATDP) provides a comprehensive suite of validated experimental protocols for evaluating potential pharmacotherapies [6]. These protocols are critical for generating reproducible and comparable data across different research programs. The methodologies are tailored to specific substance classes and target different aspects of the addiction cycle, as outlined in Table 2.

Table 2: NIDA ATDP Preclinical Testing Protocols for Substance Use Disorders [6]

| Target Substance | Key Behavioral Assays | Primary Measured Construct | Linked ANA Domain |

|---|---|---|---|

| Opioids | Oxycodone withdrawal (spontaneous/precipitated); Oxycodone cue-induced reinstatement of seeking | Physical dependence & negative affect; Relapse vulnerability | Negative Emotionality; Incentive Salience |

| Cocaine / Methamphetamine | Drug discrimination; Cue/Prime/Stress-induced reinstatement of cocaine seeking; Intracranial self-stimulation | Interoceptive drug effects; Relapse vulnerability; Reward function | Incentive Salience; Negative Emotionality |

| Nicotine | Withdrawal (spontaneous/precipitated); Cue-induced reinstatement of nicotine seeking | Physical dependence & negative affect; Relapse vulnerability | Negative Emotionality; Incentive Salience |

| Predictive Safety | Cytochrome P450 interactions; Ames test for mutagenicity; Comprehensive in vitro proarrhythmia assay (CiPA) | Drug metabolism & interactions; Genotoxicity; Cardiovascular risk | (General Safety Pharmacology) |

The experimental workflow for validating a novel compound typically follows a staged approach:

- In Vitro Screening: Initial assessment of compound binding and function at target receptors (e.g., opioid or dopamine receptors) [6].

- Lead Characterization: Selected compounds undergo behavioral testing in established models relevant to SUDs, such as:

- Self-Administration: Measures drug-taking behavior.

- Reinstatement: Models relapse by using cues, stress, or a small prime dose of the drug to re-initiate drug-seeking behavior after a period of extinction.

- Intracranial Self-Stimulation (ICSS): Assesses brain reward function; drugs of abuse typically lower the threshold for ICSS, while withdrawal raises it [6].

- Safety Pharmacology: Promising candidates are evaluated for potential toxicity, including mutagenicity and cardiac risk, using standardized in vitro and in silico assays [6].

Figure 2. Preclinical Compound Evaluation Workflow. This diagram outlines the multi-stage experimental protocol used by programs like NIDA's Addiction Treatment Discovery Program (ATDP) to evaluate the efficacy and safety of novel compounds for substance use disorders [6].

For researchers investigating the addiction cycle, a standardized set of tools and resources is critical for ensuring reproducibility and facilitating direct comparison of findings across studies. Table 3 details essential research solutions and platforms relevant to both preclinical and clinical research in this field.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Resources for Addiction Neurobiology

| Resource Category | Specific Tool / Platform | Primary Function / Application |

|---|---|---|

| Preclinical Behavioral Assays | NIDA's Addiction Treatment Discovery Program (ATDP) [6] | Provides standardized, blinded preclinical testing of compounds for effects on drug taking, reinstatement, and withdrawal across multiple substance classes. |

| Human Brain Imaging | Ultra-High-Field MRI (e.g., 11.7T Iseult system) [7] | Enables unprecedented resolution for in vivo examination of human brain structure and function, allowing finer analysis of circuits like the basal ganglia and prefrontal cortex. |

| Digital Brain Models | Virtual Epileptic Patient; Digital Twins [7] | Personalized brain models and continuously updated digital twins can be adapted to simulate the effects of drugs or treatments on specific neural circuits involved in addiction. |

| Standardized Assessment Battery | ANA Battery (Computerized Tasks & Self-Report) [4] | A curated set of validated behavioral tasks and questionnaires designed to operationalize and measure the three core ANA domains (IS, NE, EF) in human subjects. |

| Data & Analysis Repositories | NIH BRAIN Initiative Data Archives [8] | Public, integrated repositories for large-scale neuroimaging and neurophysiological datasets, promoting data sharing and collaborative analysis. |

The deconstruction of the addiction cycle into its constituent neural circuits—from the reward-driven basal ganglia to the stress-responsive extended amygdala and the control-deficient prefrontal cortex—provides a robust neurobiological framework for understanding this disorder. The Addictions Neuroclinical Assessment (ANA) successfully translates this framework into a measurable, clinically relevant tool that addresses the critical problem of heterogeneity among affected individuals [3] [4]. The validation of its three core domains through standardized batteries confirms the utility of this approach and reveals additional dimensionality within each domain, such as the separation of "alcohol motivation" from "alcohol insensitivity" within the Incentive Salience domain [4].

Future research and drug development will be shaped by several key trends. The integration of genomic data and artificial intelligence, such as the use of polygenic risk scores, is poised to enhance the personalization of addiction medicine [9]. Furthermore, initiatives like the BRAIN Initiative 2025 are driving the development of innovative technologies to map and modulate neural circuits with ever-greater precision, which will undoubtedly refine our models of the addicted brain [8]. Finally, the emergence of digital therapeutics and device-based treatments (e.g., transcranial magnetic stimulation) offers new avenues for directly targeting the dysregulated circuits identified in the addiction cycle, providing hope for more effective and personalized interventions [6]. For researchers and drug development professionals, leveraging standardized frameworks like the ANA and validated preclinical protocols like those in the ATDP will be essential for translating these advancing technologies into tangible improvements in patient care.

Introducing the Addictions Neuroclinical Assessment (ANA) Framework

Theoretical Foundation and Neurobiological Basis

The Addictions Neuroclinical Assessment (ANA) is a neuroscience-informed framework designed to address the profound clinical and etiological heterogeneity observed among individuals diagnosed with addictive disorders (AD) [3]. Developed to translate advancements in neurobiology into clinical practice, the ANA proposes that addiction is driven by dysregulation in three core neurofunctional domains, each tied to a specific phase in the cycle of addiction [10] [4]. This model moves beyond traditional, purely symptom-based diagnostic systems like the DSM-5 by focusing on the underlying psychological processes and neurocircuitry that manifest as addictive behavior [3].

The framework is conceptually aligned with the Research Domain Criteria (RDoC) initiative and is directly built upon a well-validated three-stage neurobiological model of addiction: binge/intoxication, withdrawal/negative affect, and preoccupation/anticipation [3] [10]. The ANA maps specific neuroclinical domains onto these stages to characterize an individual's addiction phenotype more precisely [4].

Table: Core Neurofunctional Domains of the ANA Framework

| ANA Domain | Associated Addiction Stage | Primary Brain Circuitry | Core Neuropsychological Process |

|---|---|---|---|

| Incentive Salience | Binge/Intoxication | Basal Ganglia; Mesolimbic Pathway | Attribution of motivational value to substance-related cues; habit formation [10] [4] |

| Negative Emotionality | Withdrawal/Negative Affect | Extended Amygdala ("Anti-reward" System) | Stress, irritability, anxiety, and dysphoria during withdrawal; driven by negative reinforcement [10] [4] |

| Executive Function | Preoccupation/Anticipation | Prefrontal Cortex | Deficits in inhibitory control, decision-making, emotional regulation, and planning [10] [4] |

Experimental Validation and Domain Factorization

A pivotal 2024 cross-sectional study (N=300) systematically evaluated the ANA battery's construct validity, moving beyond prior validation efforts that relied on secondary data analysis [4]. This study employed a standardized collection of behavioral tasks and self-report measures to assess the three domains, followed by factor analyses to elucidate their underlying dimensionality.

The findings revealed that each broad ANA domain is composed of distinct, measurable subfactors, providing a more nuanced understanding of the addiction phenotype [4]. The study identified ten subfactors across the three domains, with specific subfactors showing superior utility in classifying individuals with problematic drinking and AUD.

Table: Factor Structure and Classification Utility of ANA Domains

| ANA Domain | Identified Subfactors | Key Assessment Examples | Strongest Classifiers for AUD |

|---|---|---|---|

| Incentive Salience | Alcohol Motivation; Alcohol Insensitivity | Alcohol Cue Reactivity Tasks | Alcohol Motivation; Alcohol Insensitivity [4] |

| Negative Emotionality | Internalizing; Externalizing; Psychological Strength | Negative Emotion Scales; Distress Tolerance Tasks | Internalizing [4] |

| Executive Function | Inhibitory Control; Working Memory; Rumination; Interoception; Impulsivity | Go/No-Go Task; N-Back Task; Self-Control Scales | Impulsivity [4] |

The experimental protocol was rigorous [4]. Participants across the drinking spectrum completed the ANA battery administered via computer in four randomized testing blocks. The battery integrated performance-based neurocognitive tasks with self-report questionnaires. All participants provided informed consent and had a negative breath alcohol concentration at testing; inpatient participants were tested post-detoxification. Statistical analyses included exploratory and confirmatory factor analysis on split-half samples to identify latent factors, and receiver operating characteristics (ROC) analyses to determine the classification power of each factor for AUD.

ANA Framework: From Addiction Cycle to Measurable Factors

Comparative Analysis with Alternative Assessment Approaches

The ANA framework differs fundamentally from other common assessment strategies in its theoretical grounding, structure, and objectives.

Table: Comparison of the ANA Framework with Other Assessment Approaches

| Assessment Approach | Theoretical Basis | Primary Measurement Focus | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ANA Framework | Neurocircuitry-derived functional domains | Neuropsychological processes and behaviors linked to addiction stages | Captures etiological heterogeneity; potential for personalized treatment targeting; strong neurobiological validity [3] [4] | Longer assessment time; requires further validation for clinical deployment [4] |

| Diagnostic Criteria (e.g., DSM-5) | Clinical symptomatology and life impact | Presence or absence of pre-defined behavioral symptoms | High inter-rater reliability; diagnostic standardization; widely adopted [3] | Outcome-based rather than process-based; masks underlying heterogeneity [3] |

| Traditional Severity Scales (e.g., ASI) | Multidimensional psychosocial problems | Severity of consequences across life domains (e.g., employment, legal, family) | Comprehensive view of psychosocial functioning; tracks broad treatment outcomes [11] | Limited insight into specific neurocognitive mechanisms driving addiction [3] |

| Emerging Digital Tools (e.g., Cumulus Battery) | Classic neurobehavioral paradigms | High-frequency, repeatable cognitive performance metrics (e.g., reaction time, working memory) | Sensitive to subtle change; suitable for remote/decentralized trials; reduces participant burden [12] | May not fully cover motivational/affective ANA domains; often validated for specific impairments (e.g., alcohol challenge) [12] |

| Integrated ML Screening (e.g., CRAFFT 2.1 + Genetics) | Polygenic risk and behavioral screening | Aggregate risk score derived from genetic markers and self-reported behavior | Aims for early detection and prediction; potential for high-throughput screening [13] | Does not provide deep neuroclinical phenotyping for mechanistic intervention [13] |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Implementing the ANA framework in a research context requires a multi-modal toolkit designed to capture data across its core domains.

Table: Essential Research Materials for ANA Implementation

| Tool Category | Specific Instrument / Technology | Primary Function in ANA Research |

|---|---|---|

| Behavioral Task Software | Inquisit 5 (Millisecond Software LLC) | Administration and precise timing of standardized neurocognitive tasks (e.g., Go/No-Go, N-Back) [4] |

| Self-Report Metrics | Standardized Questionnaires (e.g., OCDS, ADS items) | Assess subjective experiences of craving, withdrawal, and emotional states that complement performance data [4] |

| Clinical Interview Schedule | Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-5 (SCID-5) | Determines formal AUD/SUD diagnosis and comorbid conditions for participant characterization [4] |

| Alcohol Use Assessment | Timeline Followback (TLFB); Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT) | Quantifies past alcohol consumption patterns and screens for problematic use [4] |

| Digital Cognitive Platform | Cumulus Neuroscience Cognitive Assessment Platform | Enables high-frequency, remote assessment of cognitive domains relevant to Executive Function (e.g., DSST, N-Back) [12] |

| Biochemical Verification | Breathalyzer (e.g., Alco-Sensor) | Verifies a negative breath alcohol concentration (BAC) at the time of testing to ensure data integrity [4] |

ANA Validation Study Workflow

The ANA framework represents a significant paradigm shift in addiction assessment, moving from a syndromal classification to a neurofunctionally-grounded phenotyping approach. Its core strength lies in its ability to deconstruct the heterogeneity of addictive disorders into measurable, mechanistically relevant domains with established neural substrates [3] [4].

For researchers and drug development professionals, this framework offers a powerful tool for stratifying patient populations in clinical trials, potentially leading to more targeted and effective interventions. The identification of specific subfactors, such as alcohol motivation and impulsivity, provides a roadmap for developing therapies that target precise neurocognitive processes rather than the broad diagnosis of AUD [4]. As the field advances, integrating the ANA with emerging digital assessment platforms and genetic risk data holds the promise of creating a comprehensive, multi-level understanding of addiction, ultimately paving the way for truly personalized medicine in the treatment of substance use disorders.

Addiction is increasingly understood through a neurobiological framework that identifies three core neurofunctional domains which underlie the disorder's development and persistence. These domains—executive dysfunction, incentive salience, and negative emotionality—map onto specific neural circuits and represent distinct yet interacting mechanisms that drive the addiction cycle [10] [14]. Historically, addiction was misconceived as a moral failing, but contemporary neuroscience has revealed it to be a chronic brain disorder characterized by specific neuroadaptations that transcend mere substance use [10]. The identification and validation of these three domains have emerged from decades of animal and human research, providing a more nuanced understanding of why individuals persist in substance use despite negative consequences and why relapse rates remain persistently high [14] [15].

The neurobiological model of addiction describes a repeating cycle with three distinct stages: binge/intoxication, withdrawal/negative affect, and preoccupation/anticipation [10]. Each stage engages specific brain regions and corresponds to the core neurofunctional domains. The binge/intoxication stage primarily involves incentive salience processes centered in the basal ganglia, the withdrawal/negative affect stage engages negative emotionality systems in the extended amygdala, and the preoccupation/anticipation stage is governed by executive function circuits in the prefrontal cortex [10]. Understanding these domains and their interactions provides a framework for developing targeted assessment instruments and personalized treatment approaches for substance use disorders (SUDs) [14].

Domain Comparison: Neurocircuitry, Behavioral Manifestations, and Assessment

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Core Neurofunctional Domains in Addiction

| Domain | Primary Neural Substrates | Key Neurotransmitters/Systems | Behavioral Manifestations | Associated Addiction Stage |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Executive Dysfunction | Prefrontal cortex (PFC), dorsolateral PFC, anterior cingulate cortex [10] | Dopamine, glutamate imbalance [10] | Reduced impulse control, poor decision-making, inability to regulate drug-seeking behavior, diminished cognitive flexibility [10] [16] | Preoccupation/Anticipation [10] |

| Incentive Salience | Basal ganglia, nucleus accumbens (NAc), ventral striatum [10] [17] | Dopamine (mesolimbic pathway), opioid peptides [10] [17] | Cue-triggered "wanting," compulsive drug-seeking, motivation for drug rewards over natural rewards, habits [10] [17] | Binge/Intoxication [10] |

| Negative Emotionality | Extended amygdala (BNST, CeA), bed nucleus of stria terminalis, central nucleus of amygdala [10] [18] | CRF, dynorphin, norepinephrine, decreased dopamine in NAc [10] [18] [15] | Hyperkatifeia (heightened negative emotional state), irritability, anxiety, dysphoria, emotional pain [10] [18] [15] | Withdrawal/Negative Affect [10] |

Table 2: Quantitative Assessment of Domain Impairment in Substance Use Disorders

| Assessment Measure | Domain Measured | Key Findings in SUD Populations | Effect Size (Hedges' g or Comparable) | Reliability/Validity Metrics |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Difficulties in Emotion Regulation Scale (DERS) | Negative Emotionality [19] | SUDs showed significantly greater emotion regulation difficulties vs. controls | g = 1.05 (95% CI: 0.86-1.24) [19] | Excellent internal consistency (α = 0.77-0.96) [19] |

| DERS Subscales Analysis | Negative Emotionality | Largest deficits in Strategies and Impulse subscales [19] | Mean difference: 21.44 (95% CI: 16.49-26.40) [19] | Good test-retest reliability (ρI = 0.88) [19] |

| Emotion Regulation Questionnaire (ERQ) | Negative Emotionality/Executive Function [19] | Greater use of expressive suppression in SUDs vs. controls | g = 0.76 (95% CI: 0.25-1.28) [19] | Established construct validity [19] |

| Latent Profile Analysis (NKI-RS Sample) | All Three Domains [14] | Identified three subtypes: Reward (27%), Cognitive (40%), Relief (20%) in past SUDs | Cohen's D range: 0.4-2.8 across domains [14] | Comprehensive phenotypic assessment (74 subscales) [14] |

Neurobiological Validation of Assessment Instruments

The Addictions Neuroclinical Assessment (ANA) Framework

The Addictions Neuroclinical Assessment (ANA) represents a significant advancement in translating the three-stage neurobiological model of addiction into clinical practice. Developed by the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA), this clinical instrument translates the three neurobiological stages of addiction into three measurable neurofunctional domains: incentive salience, negative emotionality, and executive dysfunction [10]. The ANA provides a structured approach to assess these domains at the bedside, allowing clinicians to move beyond generic diagnostic criteria and instead employ targeted treatments for specific clinical presentations [10]. This neurobiologically-informed framework represents a paradigm shift in addiction assessment, directly addressing the heterogeneous nature of SUDs by recognizing that different individuals may exhibit distinct patterns of impairment across these domains.

Validation of the ANA framework comes from empirical studies demonstrating that these domains represent meaningful subgroups within SUD populations. Research utilizing latent profile analysis in community samples has identified three distinct neurobehavioral subtypes corresponding to these domains: a "Reward type" with heightened incentive salience, a "Cognitive type" with executive dysfunction, and a "Relief type" with prominent negative emotionality [14]. These subtypes were equally distributed across different primary substance use disorders and genders, supporting the transdiagnostic nature of these domains and their relevance across the spectrum of addictive disorders [14].

Standardized Assessment Instruments and Methodologies

Several well-validated assessment instruments provide the methodological foundation for evaluating the core neurofunctional domains in research and clinical settings. These instruments vary in their structure, focus, and application, allowing researchers to select the most appropriate tools based on their specific objectives.

Table 3: Key Assessment Instruments for Addiction Research

| Instrument | Format | Primary Application | Domains Assessed | Administration Time | Training Requirements |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Addiction Severity Index (ASI) | Semi-structured [20] | Treatment planning, service needs assessment [20] | Functioning in 7 domains (alcohol, drugs, psychiatric, etc.) [20] | 45-60 min + scoring [20] | 2-day classroom session [20] |

| Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV (SCID) | Semi-structured [20] | Diagnostic consistency for research [20] | Alcohol/drug dependence and abuse, psychiatric comorbidities [20] | 90 minutes [20] | User's guide, 1-2 days on-site training [20] |

| Composite International Diagnostic Interview (CIDI) | Fully structured [20] | Large-scale studies, epidemiological research [20] | DSM-IV and ICD-10 substance use and mental disorders [20] | 75 minutes [20] | 2.5-3 days classroom training [20] |

| Difficulties in Emotion Regulation Scale (DERS) | Self-report [19] | Emotion regulation capacity assessment [19] | Negative Emotionality (Strategies, Impulse subscales most sensitive) [19] | Not specified | Minimal (self-report) [19] |

The selection of appropriate assessment instruments is critical for both research and clinical applications. In research, proper instrumentation can determine the success or failure of clinical trials, as demonstrated by studies of tricyclic antidepressants for substance abusers with comorbid depression. Early trials that used limited assessment tools showed minimal benefit, while later studies employing more rigorous diagnostic instruments consistently demonstrated efficacy [20]. This highlights how assessment methodology directly impacts the validity and interpretation of research findings.

Experimental Protocols and Neural Circuit Mapping

Neuroimaging Protocols for Domain Assessment

Functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) has become a cornerstone technology for investigating the neural substrates of the three core neurofunctional domains in addiction. Task-based fMRI protocols typically involve presenting emotionally salient stimuli while measuring blood-oxygen-level-dependent (BOLD) responses in specific brain regions [15]. These tasks can be passive (e.g., viewing emotional faces or aversive images) or active (e.g., requiring conscious emotion regulation strategies like reappraisal) [15]. The experimental workflow generally involves: (1) participant screening and diagnosis using structured clinical interviews; (2) abstinence verification (when relevant); (3) fMRI task administration; (4) preprocessing of neuroimaging data; and (5) statistical analysis of brain activation patterns.

For the negative emotionality domain, common paradigms include facial emotion processing tasks (e.g., identifying emotions in faces) and aversive stimulus viewing (e.g., unpleasant images) [15]. These tasks consistently engage the extended amygdala, anterior insula, anterior cingulate cortex (ACC), and medial prefrontal cortex (mPFC) [15]. Research has revealed substance-specific patterns of dysregulation, with alcohol dependence typically showing blunted activation in these regions, while cocaine dependence often demonstrates heightened reactivity [15]. These differential patterns highlight the importance of considering substance type when interpreting neuroimaging findings.

Behavioral Paradigms for Domain-Specific Assessment

Behavioral tasks provide crucial complementary data to neuroimaging for assessing the core neurofunctional domains. For executive dysfunction, common paradigms include the Go/No-Go task (measuring response inhibition), Stroop task (assessing cognitive interference), and Iowa Gambling Task (evaluating decision-making) [16]. These tasks probe the "Stop system" within the prefrontal cortex that is responsible for overriding strong urges to use substances [10].

For incentive salience, behavioral protocols often involve Pavlovian conditioning procedures where previously neutral stimuli are paired with drug rewards [16]. These paradigms measure the attribution of incentive salience to drug-paired cues, a process dependent on dopaminergic transmission in the mesolimbic pathway [17] [16]. Sign-tracking behavior (approaching and interacting with reward-predictive cues) provides a validated behavioral measure of excessive incentive salience in animal models, with parallels in human studies [17].

The negative emotionality domain is frequently assessed using stress reactivity paradigms, affective picture viewing tasks, and measures of distress tolerance [15] [19]. These protocols capture the hyperkatifeia (heightened negative emotional state) that emerges during withdrawal and drives negative reinforcement [18] [15]. The experimental workflow typically involves baseline assessment, stressor induction (e.g., social stress, individualized stress scripts), and measurement of subjective, physiological, and neural responses.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 4: Research Reagent Solutions for Addiction Neuroscience

| Reagent/Material | Primary Application | Specific Function in Research | Domain Relevance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV (SCID) | Diagnostic assessment [20] | Ensures diagnostic consistency and participant characterization | All domains (patient stratification) |

| fMRI with BOLD contrast | Neurocircuitry mapping [15] | Measures neural activity during domain-specific tasks | All domains (neural substrates) |

| Difficulties in Emotion Regulation Scale (DERS) | Emotion regulation assessment [19] | Quantifies multiple aspects of emotional dysregulation | Negative Emotionality |

| Emotion Regulation Questionnaire (ERQ) | Emotion regulation strategies [19] | Measures cognitive reappraisal and expressive suppression | Negative Emotionality/Executive Function |

| Pavlovian Conditioning Apparatus | Incentive salience measurement [17] [16] | Assesses cue-reward learning and sign-tracking behavior | Incentive Salience |

| Corticotropin-Releasing Factor (CRF) Receptor Antagonists | Stress system manipulation [18] | Probes extended amygdala stress circuitry | Negative Emotionality |

| Dopamine Receptor Ligands | Dopamine system assessment [17] | Measures dopamine transmission and receptor availability | Incentive Salience |

| Go/No-Go and Stroop Tasks | Executive function assessment [16] | Measures response inhibition and cognitive control | Executive Dysfunction |

Implications for Targeted Treatment Development

The validation of three distinct neurofunctional domains in addiction has profound implications for developing targeted treatment strategies. Rather than applying one-size-fits-all approaches, this framework supports personalized interventions based on an individual's specific domain profile [14]. For those with prominent incentive salience dysregulation ("Reward type"), treatments might focus on managing cue reactivity and altering maladaptive reward learning processes [17] [14]. For individuals with executive dysfunction as their primary deficit ("Cognitive type"), cognitive remediation, working memory training, and interventions that strengthen prefrontal control systems may be most beneficial [14]. For those whose addiction is maintained primarily by negative emotionality ("Relief type"), treatments targeting the extended amygdala stress systems (e.g., CRF antagonists, neuropeptide Y enhancers) and emotion regulation skills training would be indicated [18] [14] [15].

This domain-based approach also informs medication development. Rather than seeking a single medication for all forms of addiction, pharmaceutical research can target specific neurochemical systems underlying each domain. For negative emotionality, compounds that modulate the brain's stress systems—including CRF receptor antagonists, neuropeptide Y enhancers, nociceptin agonists, and endocannabinoid system modulators—show particular promise [18]. For incentive salience, medications that normalize dopaminergic transmission without producing anhedonia represent a viable strategy [17]. For executive dysfunction, procognitive agents that enhance prefrontal function could improve self-regulation and treatment adherence [10] [14].

The recognition of these neurofunctional domains also supports the development of biomarker-driven clinical trials. By stratifying participants based on their domain profiles, researchers can achieve more homogeneous study populations and better detect treatment effects that might be obscured in heterogeneous samples [14]. This approach aligns with precision medicine initiatives and represents a promising path forward for addressing the high relapse rates that have persistently challenged addiction treatment [14] [15].

Limitations of Symptom-Based Nosology in DSM-5 and ICD-10

The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition (DSM-5) and the International Classification of Diseases, 10th Revision (ICD-10) represent the two predominant systems for classifying mental disorders worldwide. These symptom-based classifications have largely become an integral part of the body of knowledge of psychiatrists throughout the world and instruments they constantly refer to [21]. Both systems are descriptive classifications that categorize mental disorders based upon a constellation or syndrome of symptoms and signs, with symptoms representing the patient's reports of personal experiences and signs being observable behaviors [22]. The fundamental premise underlying these systems is that mental disorders can be identified through specific patterns of symptoms that cluster together, and that these patterns represent distinct diagnostic entities.

However, particularly in the case of psychiatry, equating nosological classification with diagnosis and validity is far from always being the case [21]. From a scientific point of view, these two most up-to-date classification systems in use today may be considered as the theoretical basis of current psychiatric nosology, yet they face significant challenges, especially in the context of addiction disorders and their neurobiological validation. The essential limitation lies in the fact that in the absence of biological markers for most psychopathological disorders, diagnostic features were based primarily on clinical descriptions, resulting in "official" nosological groupings that may not accurately reflect underlying neurobiological realities [21]. This paper examines the specific limitations of these symptom-based approaches, presents experimental data highlighting their deficiencies, and explores the neurobiological frameworks that may inform future diagnostic paradigms.

Comparative Analysis of DSM-5 and ICD-10 Diagnostic Approaches

Structural and Conceptual Differences in Classification

The DSM-5 and ICD-10 systems demonstrate significant structural and conceptual differences in their approach to diagnosing substance use and addictive disorders. The ICD-10 utilizes a categorical approach with two primary diagnoses: harmful use (F1x.1) and dependence (F1x.2). Harmful use is broadly defined as a pattern of psychoactive substance use that causes damage to mental or physical health, while dependence requires the presence of three or more of six specific criteria occurring within a 12-month period: strong desire or compulsion to take the substance; difficulties in controlling substance use; withdrawal; tolerance; neglect of alternative pleasurable activities or interests; and continued use despite clear evidence of harmful consequences [23].

In contrast, DSM-5 conceptualizes substance use disorder (SUD) classification through a dimensional approach with a single unified SUD category of graded clinical severity. The DSM-5 includes 11 total SUD criteria and features three severity specifiers based on the total number of positive criteria: mild (2-3 positive criteria), moderate (4-5 positive criteria), and severe (6 or more positive criteria) [23]. This represents a significant shift from the traditional categorical approach toward a more graduated conceptualization of substance-related problems.

Table 1: Diagnostic Criteria Comparison Between DSM-5 and ICD-10 for Substance Use Disorders

| Feature | DSM-5 | ICD-10 (Clinical Version) | ICD-10 (Research Version) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Conceptual Approach | Dimensional | Categorical | Categorical |

| Primary Diagnoses | Substance use disorder with severity specifiers | Harmful use, Dependence | Harmful use, Dependence |

| Number of Criteria | 11 | 6 for dependence | 6 for dependence |

| Severity Classification | Mild (2-3 symptoms), Moderate (4-5 symptoms), Severe (6+ symptoms) | Binary (presence/absence of dependence) | Binary (presence/absence of dependence) |

| Harmful Use Definition | Incorporated into mild SUD | Pattern causing mental/physical damage | Expanded to include impaired judgment/dysfunctional behavior |

| Diagnostic Focus | Continuum of severity | Distinct categories | Distinct categories with broader harmful use criteria |

Diagnostic Concordance and Empirical Validation

Empirical studies examining the concordance between DSM-5 and ICD-10 diagnoses reveal significant limitations in their alignment, particularly for moderate severity cases. Research conducted with a large state prison sample (n = 7,672) demonstrated that while prevalence rates of cannabis use disorders were comparable across classification systems, diagnostic concordance varied substantially by severity level [23].

The vast majority of inmates with no DSM-5 diagnosis continued to have no diagnosis per the ICD-10, and a similar proportion with a DSM-5 severe diagnosis received an ICD-10 dependence diagnosis. However, most of the variation in diagnostic classifications was accounted for by those with a DSM-5 moderate diagnosis, in that approximately half of these cases received an ICD-10 dependence diagnosis while the remaining cases received a harmful use diagnosis [23]. This discordance highlights fundamental differences in how the two systems conceptualize the threshold for dependence.

Table 2: Diagnostic Concordance for Cannabis Use Disorders Between DSM-5 and ICD-10 (N=7,672)

| DSM-5 Diagnosis | ICD-10 Dependence Diagnosis | ICD-10 Harmful Use Diagnosis | No ICD-10 Diagnosis | Concordance Level |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Severe (6+ symptoms) | 92.3% | 6.1% | 1.6% | Excellent |

| Moderate (4-5 symptoms) | 48.7% | 47.2% | 4.1% | Poor |

| Mild (2-3 symptoms) | 12.4% | 72.6% | 15.0% | Fair to Good |

| No Diagnosis | 2.3% | 8.9% | 88.8% | Excellent |

The kappa coefficient analysis between algorithmic diagnoses and expert clinician diagnoses further reveals validity concerns. A study comparing DSM-IV and ICD-10 diagnoses of schizophrenia found only marginal correlation between expert clinician and algorithmic diagnoses (kappa = 0.34 for DSM-IV; kappa = 0.37 for ICD-10), where kappa values below 0.4 indicate marginal correlation [21]. This suggests that instrumentally generated diagnoses may have relatively low validity when compared with clinician expert diagnoses derived from holistic assessment.

Methodological Limitations in Diagnostic Validation

Experimental Protocols for Diagnostic Reliability Assessment

Research examining the validity of symptom-based nosology employs rigorous methodological approaches to compare diagnostic outcomes. One representative study protocol conducted at the Mental Health Clinical Research Center of the University of Iowa College of Medicine evaluated the reproducibility and validity of ICD-10 and DSM-IV clinical and operational diagnoses of schizophrenia [21]. The experimental workflow involved multiple structured components:

Subject Recruitment and Assessment: The study analyzed medical records of 43 subjects from the DSM-IV Field Trial Iowa Site. Each participant underwent comprehensive assessment through both unstructured clinical interviews conducted by experienced clinicians and structured diagnostic interviews using the Comprehensive Assessment of Symptoms and History (CASH) instrument.

Diagnostic Formulation: Two diagnostic methods were applied for each subject: (1) Clinical expert diagnoses derived from unstructured interviews employing a "holistic approach"; and (2) Algorithmic diagnoses generated through computer scoring of structured CASH interviews with diagnostic algorithms applied directly to the recorded symptoms.

Algorithm Development: Researchers prepared specific diagnostic algorithms for DSM-IV and ICD-10 diagnoses of schizophrenia, programming them for computerized scoring to ensure consistency and eliminate rater bias in application of diagnostic criteria.

Statistical Analysis: The correlation between algorithmic diagnoses and expert clinician diagnoses was quantified by calculating kappa coefficients, with established interpretive guidelines: kappa > 0.75 (excellent correlation), 0.4 < kappa < 0.74 (good correlation), and kappa < 0.4 (marginal correlation) [21].

This methodological approach allowed researchers to test the hypothesis that, assuming the expert clinician diagnosis represents a valid "gold standard," observation of a low correlation between clinician and algorithmic diagnoses would reflect low validity of the algorithmic diagnosis.

Key Research Reagents and Assessment Tools

The experimental assessment of diagnostic validity relies on specialized instruments and methodological tools. The following research reagents represent essential components for conducting diagnostic validation studies in psychiatry:

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Diagnostic Validation Studies

| Research Tool | Function | Application in Validation Studies |

|---|---|---|

| Comprehensive Assessment of Symptoms and History (CASH) | Structured interview for recording signs, symptoms, and history | Provides standardized data for algorithmic diagnosis [21] |

| Schedule for Clinical Assessment in Neuropsychiatry (SCAN) | Structured diagnostic interview for psychopathology | Enables systematic assessment of mental status [21] |

| Substance Use Disorder Diagnostic Schedule-IV (SUDDS-IV) | Automated diagnostic instrument for substance use disorders | Generates DSM and ICD compatible diagnoses [23] |

| Kappa Coefficient Statistics | Measures inter-rater reliability beyond chance agreement | Quantifies diagnostic concordance between systems [21] |

| Diagnostic Algorithms | Computerized criteria application for DSM/ICD diagnoses | Eliminates clinical judgment in operational diagnoses [21] |

| Addictions Neuroclinical Assessment (ANA) | Translates neurobiological stages to clinical domains | Bridges neurobiology and diagnostic assessment [10] |

Neurobiological Frameworks Challenging Symptom-Based Nosology

The Addiction Cycle and Neurobiological Stages

Contemporary models of addiction utilize a neurobiological framework that fundamentally challenges symptom-based diagnostic approaches. This framework defines addiction as a chronic and relapsing disorder marked by specific neuroadaptations that predispose an individual to pursue substances irrespective of potential consequences [10]. These neuroadaptations occur in three distinct neurobiological stages that cut across traditional diagnostic categories:

Binge/Intoxication Stage: During this initial stage, dopaminergic firing in the basal ganglia increases for substance-associated cues while diminishing for the substance itself, a phenomenon known as incentive salience [10]. The reward system activates two significant pathways: the mesolimbic pathway (responsible for reward and positive reinforcement via dopamine and opioid peptides) and the nigrostriatal pathway (controlling habitual motor function and behavior) [10].

Withdrawal/Negative Affect Stage: This stage involves two primary neuroadaptations. First, chronic reward exposure decreases dopaminergic tone in the nucleus accumbens while shifting the glutaminergic-GABAergic balance toward increased glutaminergic tone. Second, there is increased recruitment of stress circuits in the extended amygdala (the "anti-reward" system), leading to increased release of stress mediators including dynorphin, corticotropin-releasing factor, norepinephrine, and orexin [10].

Preoccupation/Anticipation Stage: The signature of this phase is preoccupation with using the substance ("cravings"), primarily involving the prefrontal cortex. Researchers have identified two systems within the PFC: a "Go system" (involving decisions requiring considerable attention and planning) and a "Stop system" (responsible for inhibitory control) [10]. In addiction, the balance between these systems becomes disrupted, leading to diminished executive control.

Neurobiological Theories of Addiction

Several neurobiological theories provide comprehensive explanations for addictive processes that transcend symptom-based classifications:

Opponent-Process Theory: Developed by Solomon and Corbit, this theory posits that when a positive affective response (primary process) is activated by drug consumption, mechanisms simultaneously initiate an opposite response (opponent process) to restore homeostasis [24]. Repeated drug consumption strengthens the opponent process, leading to tolerance (as the pleasurable primary process is counteracted) and withdrawal syndrome (as the strengthened opponent process creates prolonged discomfort after drug effects diminish) [24].

Dopaminergic Hypothesis of Addiction: This theory establishes that the reward level induced by a drug is directly related to the phasic increase in dopamine levels in the nucleus accumbens [24]. The mesolimbic cortical dopaminergic pathway, with projections from the ventral tegmental area to the nucleus accumbens and connections to hippocampus, prefrontal cortex, amygdala, and other structures, represents the common neural substrate for natural rewards and drugs [24].

Allostasis Theory: An extension of opponent-process theory, this model emphasizes the chronic dysregulation of brain reward and stress systems beyond homeostasis, creating a new set point that perpetuates addictive behavior through continued substance use [24].

These neurobiological models demonstrate that addiction involves specific, measurable alterations in brain structure and function that are not adequately captured by current symptom-based diagnostic criteria.

Emerging Alternatives to Traditional Nosology

The Hierarchical Taxonomy of Psychopathology (HiTOP)

The HiTOP framework was developed by a consortium of psychopathology researchers as an alternative to traditional diagnostic categories. This system provides an empirically based, fully dimensional organization of psychopathology by subjecting current diagnoses, syndromes, and symptoms to multivariate factor-analytic procedures [25]. HiTOP posits that psychopathology is hierarchically structured with symptoms/signs (level 1) nested within syndromes/traits (level 2), which are nested within factors (level 3), with broad spectra at the highest level (level 4) [25].

The model identifies several broad spectra, including internalizing pathology (encompassing fear, distress, eating pathology, and sexual problems), externalizing pathology (comprising disinhibited and antagonistic behaviors, substance abuse, and antisocial behavior), thought disorder (psychosis spectrum disorders), and detachment (pathological introversion) [25]. This dimensional approach addresses the substantial heterogeneity within traditional diagnostic categories and the problem of excessive comorbidity between putatively independent disorders.

Research Domain Criteria (RDoC)

The RDoC program was initiated by the National Institute of Mental Health as a dimensional and translational alternative to current psychiatric classification. Unlike the DSM/ICD top-down approach that defines disorders based on signs and symptoms, RDoC encourages a bottom-up approach that examines the normal distribution of traits or characteristics, the brain systems implementing these functions, and factors causing dysregulation that results in psychopathology [25].

The RDoC framework organizes research around five neurobiological domains: negative valence systems (acute threat, potential threat, sustained threat, loss, frustrative nonreward), positive valence systems (reward responsiveness, reward learning, habit), cognitive systems (attention, perception, memory, cognitive control), systems for social processes (attachment, social communication, perception of self/others), and arousal/modulatory systems (circadian rhythms, sleep/wake) [25]. This approach aims to address the lack of pathophysiological specificity within and between traditional psychiatric diagnoses.

Implications for Research and Drug Development

The limitations of symptom-based nosology have significant implications for research and pharmaceutical development. The inherent limitations of heterogeneous and fuzzy DSM/ICD diagnoses have been disclosed by functional neuroimaging studies demonstrating that no single pattern of aberrant brain activation consistently replicates across experiments [25]. Distinct pathophysiological mechanisms subsumed under the same diagnostic category are seen by the pharmaceutical industry as a major cause of the low-response rate of psychiatric drugs [25].

The neurobiological stages of addiction (binge/intoxication, withdrawal/negative affect, preoccupation/anticipation) offer an alternative framework for developing targeted treatments. The Addictions Neuroclinical Assessment (ANA) translates these three neurobiological stages into three neurofunctional domains: incentive salience, negative emotionality, and executive dysfunction [10]. This approach allows clinicians and researchers to employ targeted treatments for specific clinical presentations based on underlying neurobiology rather than symptom clusters.

Emerging evidence suggests that dimensional approaches like HiTOP and RDoC can advance etiological research, promote development of new treatments, and facilitate detection of genetic and neurobiological markers for application in diagnostic clinical tests [25]. These frameworks acknowledge that psychopathology is not organized according to the DSM/ICD scheme, and that adopting fully dimensional representations of mental disorders substantially improves reliability and validity beyond categorical measures [25].

The symptom-based nosology embodied in DSM-5 and ICD-10 demonstrates significant limitations when evaluated through the lens of contemporary neurobiological research. Empirical evidence reveals only marginal correlation between operational diagnoses and clinician expert diagnoses, poor diagnostic concordance for moderate severity cases, and inadequate representation of the underlying neurobiological processes in addiction. The emerging understanding of addiction as a cyclic process involving specific neuroadaptations in the basal ganglia, extended amygdala, and prefrontal cortex challenges the categorical, symptom-based approach of traditional diagnostic systems.

Alternative frameworks such as the Hierarchical Taxonomy of Psychopathology and Research Domain Criteria offer promising dimensional approaches that better align with the neurobiological evidence. For researchers and drug development professionals, these approaches provide opportunities to develop more targeted interventions based on specific neurofunctional domains rather than heterogeneous symptom clusters. Future diagnostic systems must integrate neurobiological dimensions with clinical observation to create more valid and clinically useful classifications that ultimately advance both treatment and research in addictive disorders.

Substance use disorders (SUDs) represent a significant global public health challenge, historically understood through categorical diagnostic systems that have limited biological validity and treatment personalization. The Research Domain Criteria (RDoC) framework, initiated by the National Institute of Mental Health, marks a paradigm shift by proposing a dimensional approach that links clinical presentations with their underlying biological foundations [26]. This framework organizes core dimensions of behavior across multiple levels of analysis, from genes to circuits to behavior, viewing these aspects as varying along a continuum rather than in distinct categories [27]. For addiction science, this translational approach offers unprecedented opportunities to identify functional mechanisms that transcend traditional diagnostic boundaries and align more precisely with the neurobiological evidence [28].

The contemporary understanding of addiction utilizes a neurobiological framework that defines it as a chronic and relapsing disorder marked by specific neuroadaptations which predispose an individual to pursue substances irrespective of potential consequences [10]. These neuroadaptations occur in three distinct neurobiological stages—intoxication/binge, withdrawal/negative affect, and preoccupation/anticipation—each involving specific brain regions and circuit dysfunctions [10]. The RDoC framework provides an ideal structure for investigating these stages as dimensional constructs rather than binary diagnoses, potentially revolutionizing both assessment and intervention strategies for addictive disorders.

Theoretical Foundation: RDoC Principles and Addiction Neurobiology

Core RDoC Concepts and Domain Structure

The RDoC framework is built upon several fundamental principles that distinguish it from traditional diagnostic systems. It employs a dimensional approach to psychopathology, viewing mental functioning as occurring along continuous valid dimensions ranging from functional to pathological [26]. This approach stands in contrast to the categorical systems of ICD and DSM, which define symptoms and symptom clusters but face significant limitations due to high comorbidity, clinical heterogeneity, and exclusion of biomarkers [26]. The framework spans multiple levels of analysis, from genes to behavior, promoting multi-level analysis and integrating disciplines from psychology to neuroscience to biology [27].

RDoC organizes psychological functioning into six major domains: Negative Valence Systems (e.g., fear, anxiety), Positive Valence Systems (e.g., reward processing), Cognitive Systems (e.g., attention, memory), Social Processes (e.g., social cognition), Arousal and Regulatory Systems (e.g., sleep-wake cycles), and Sensorimotor Systems [29]. Within each domain, specific constructs and sub-constructs represent biopsychological processes and mechanisms regarded as continua between functional and pathological states [26]. Importantly, these dimensions are not considered final or static but as dynamic constructs constantly adapted to and extended by current research findings [26].

Neurocircuitry of Addiction: The Three-Stage Cycle

Addiction neurobiology is characterized by a repeating cycle of three distinct stages, each with specific neural substrates and behavioral manifestations. The intoxication/binge stage begins when an individual consumes a rewarding substance, primarily involving the basal ganglia [10]. During this stage, dopaminergic firing increases for substance-associated cues while diminishing for the substance itself—a process known as incentive salience [10]. The mesolimbic pathway, facilitating communication between the ventromedial striatum and nucleus accumbens, is responsible for the reward and positive reinforcement via direct release of dopamine and opioid peptides [10].

The withdrawal/negative affect stage comprises acute and post-acute withdrawal phenomenology, characterized by two primary neuroadaptations [10]. First, chronic reward exposure decreases dopaminergic tone in the nucleus accumbens while shifting the glutaminergic-GABAergic balance toward increased glutaminergic tone. Second, stress circuits in the extended amygdala (the "anti-reward" system) become increasingly recruited, leading to elevated release of stress mediators including dynorphin, corticotropin-releasing factor, and norepinephrine [10]. The clinical consequences present as irritability, anxiety, and dysphoria, driving further substance use through negative reinforcement.

The preoccupation/anticipation stage occurs during abstinence periods and is characterized by cravings and preoccupation with substance use [10]. This stage primarily involves the prefrontal cortex (PFC), which is responsible for executive functions including planning, task management, and regulation of thoughts, emotions, and impulses [10]. Researchers have conceptualized two systems within the PFC: a "Go system" for goal-directed behaviors requiring attention and planning, and a "Stop system" for inhibitory control—both of which become dysregulated in addiction.

Table 1: RDoC Domains Relevant to Addiction Pathology

| RDoC Domain | Relevant Addiction Constructs | Associated Neural Circuitry | Behavioral Manifestations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Positive Valence Systems | Reward learning, incentive salience, habit formation | Mesolimbic dopamine pathway, ventral striatum, basal ganglia | Compulsive drug-seeking, cue reactivity |

| Negative Valence Systems | Acute threat (fear), sustained threat (anxiety), loss | Extended amygdala, BNST, HPA axis | Withdrawal symptoms, negative affect, stress-induced relapse |

| Cognitive Systems | Executive function, cognitive control, working memory | Prefrontal cortex, anterior cingulate, dorsolateral PFC | Poor decision-making, impaired inhibitory control, cravings |

| Arousal/Regulatory Systems | Arousal, sleep-wake regulation | Brainstem, hypothalamus, thalamocortical circuits | Sleep disturbances, emotional dysregulation |

Assessment Frameworks: From Traditional Tools to RDoC-Aligned Approaches

Conventional Addiction Assessment Instruments

Traditional addiction assessment has relied on structured interviews, self-report questionnaires, and clinical observations focusing primarily on behavioral symptoms and consumption patterns. These include broad-spectrum screening tools like the Tobacco, Alcohol, Prescription Medication and Other Substance Use (TAPS) tool, which offers validated, broad-spectrum screening specifically designed for adult populations [11]. For adolescent populations, specialized instruments such as the CRAFFT 2.1 questionnaire (with six questions exploring behaviors captured by the acronym CRAFFT: Car, Relax, Alone, Forget, Family/Friends, Trouble) and BSTAD effectively address developmental considerations while enabling systematic risk stratification [11]. These tools have demonstrated high diagnostic accuracy with area under the curve values between 0.89 and 1 in validation studies [11].

Advanced severity measurement instruments used in clinical settings include the Addiction Severity Index (ASI), which employs 0-9 scoring across seven domains to enable precise measurement of treatment urgency and progress [11]. Similarly, the ASAM's six-dimensional criteria drive treatment planning by replacing outdated single-symptom approaches with multidimensional risk assessment protocols [11]. While these instruments provide valuable clinical information, they primarily operate at the level of observed behavior and self-report without systematically incorporating neurobiological data across multiple units of analysis as encouraged by the RDoC framework.

Emerging Neuroscience-Informed Assessment Paradigms

The integration of neuroscientific principles with addiction assessment has led to the development of novel frameworks that align more closely with RDoC principles. The Addictions Neuroclinical Assessment (ANA) represents a significant advancement by translating the three neurobiological stages of addiction into three neurofunctional domains: incentive salience, negative emotionality, and executive dysfunction [10]. This clinical instrument, developed by the National Institute of Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism, allows clinicians to employ targeted treatments for specific clinical presentations based on underlying neurofunctional impairments rather than symptom counts alone [10].

Complementing the ANA, alternative models like the ASPIRE framework propose a patient-centered, neuroscience-based approach for treating SUDs through shared decision-making [30]. This model tailors personalized medical care and precision medicine research to six neuroscience-based risk categories that patients report as most distressing: (A) Anhedonia/reward-deficit state; (S) Stressful/anti-reward state; (P) Pathological lack of self-control; (I) Insomnia associated with substance use; (R) Restlessness; and (E) Excessive preoccupation with seeking drug reinforcers [30]. Such approaches demonstrate how RDoC principles can be operationalized in clinical settings through concise assessment batteries that map onto biologically-based risk categories.

Table 2: Comparison of Traditional and RDoC-Aligned Assessment Approaches

| Assessment Characteristic | Traditional Assessment Tools | RDoC-Aligned Frameworks |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Focus | Behavioral symptoms, consumption patterns, psychosocial consequences | Neurofunctional domains, circuit-level dysfunctions, dimensional constructs |

| Theoretical Basis | Categorical diagnoses (DSM-5, ICD-11) | Dimensional psychopathology, neurocircuitry models |

| Typical Instruments | CRAFFT, ASI, TAPS, DSM-5 criteria | ANA, ASPIRE, neuroimaging, behavioral paradigms |

| Strengths | Standardized administration, established validity, clinical familiarity | Neurobiological validity, personalized treatment targets, transdiagnostic applicability |

| Limitations | Limited neurobiological integration, symptom focus rather than mechanisms | Assessment burden, translational challenges, limited clinical implementation |

Methodological Approaches: Experimental Protocols and Validation Studies

Latent Variable Approaches to RDoC Validation

Recent research has employed sophisticated statistical methods to empirically validate and refine the RDoC framework. A 2025 study published in Nature Communications utilized a latent variable approach with bifactor analysis to examine circuit-function relations in the RDoC framework [27]. The researchers examined 84 whole-brain task-based fMRI activation maps from 19 studies with 6192 participants, using a curated subset of 37 maps with balanced RDoC domain representation as a training set and remaining maps for internal validation [27]. External validation was conducted using 36 peak coordinate activation maps from Neurosynth, using terms of RDoC constructs as seeds for topic meta-analysis [27].

The study compared four distinct latent variable models, combining two methods of factor derivation (theory-driven RDoC factors or data-driven empirical factors) with two types of factor models (specific factor models or bifactor models) [27]. Results demonstrated that a bifactor model incorporating a task-general domain and splitting the cognitive systems domain provided better fit to task-based fMRI data than the current RDoC framework [27]. Additionally, the domain of arousal and regulatory systems was identified as underrepresented in the current framework [27]. These findings highlight how data-driven approaches can inform refinements to the RDoC structure to better reflect underlying brain circuitry.

Integrative Biopsychosocial Assessment Protocols

Comprehensive addiction assessment within an RDoC framework requires integration of data across multiple units of analysis. The TOPOWA Study (The Onward Project On Well-being and Adversity) exemplifies this approach by combining the RDoC framework with a social determinants lens to explore pathways linking social adversity to mental health challenges [29]. This study integrates diverse data sources, including biomarkers, wearable sensors, and self-report surveys, to capture multilevel influences on mental health in low-resource settings [29]. The approach demonstrates how RDoC can be adapted for community-based, context-sensitive research to support development of targeted mental health interventions.

The startle reflex potentiation method offers a low-cost, low-burden translational tool to study threat-related brain circuits in community settings where neuroimaging is not feasible [29]. This defensive response, common to all mammals, provides a practical method for examining neurobiological responses to environmental threat in individuals experiencing extreme poverty or other adverse conditions. Such methodological innovations are crucial for democratizing access to biologically informed mental health science and expanding RDoC-aligned research beyond well-resourced laboratory settings.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Essential Research Materials for RDoC-Aligned Addiction Studies

| Research Tool Category | Specific Examples | Primary Research Function | RDoC Alignment |

|---|---|---|---|

| Neuroimaging Platforms | task-based fMRI, resting-state fMRI, structural MRI | Circuit-level analysis, functional connectivity, structural correlates | Multiple units of analysis from circuits to behavior |

| Physiological Monitoring | Wearable sensors, startle reflex potentiation, heart rate variability | Arousal regulation, stress reactivity, real-world monitoring | Arousal/regulatory systems, negative valence systems |

| Genetic Analysis Tools | Polygenic risk scores, genome-wide association studies, epigenetic markers | Genetic vulnerability, gene-environment interactions, molecular mechanisms | Genetic levels of analysis, individual differences |

| Behavioral Paradigms | Monetary incentive delay task, emotional Stroop, fear conditioning | Reward processing, cognitive control, threat sensitivity | Positive/negative valence systems, cognitive systems |

| Self-Report Measures | PROMIS measures, PhenX Toolkit, ecological momentary assessment | Subjective experience, real-world functioning, symptom tracking | Self-report units of analysis, cross-level integration |

Data Integration and Analysis: Quantitative Findings and Comparative Validation

Empirical Validation of RDoC Framework

The 2025 latent variable analysis of RDoC domains provided compelling quantitative evidence regarding the framework's neural validity [27]. When conducting confirmatory factor analyses with RDoC factors, researchers found that most maps within each domain loaded significantly onto factors representing their domains (cognitive systems: 11/15; negative valence systems: 5/5; positive valence systems: 6/7; social processes: 6/6; sensorimotor systems: 4/4) [27]. Comparison of the RDoC-specific factor model with the bifactor model revealed that the bifactor model had a better fit according to all fit indices (Tukey's test, p < .001), suggesting that adding a general factor reflecting domain-general activation patterns improved model fit [27].

In data-driven analyses, parallel analysis indicated that models with eight factors or less had eigenvalues greater than expected by chance [27]. When extracting eight specific factors in data-driven confirmatory factor analyses, all but two maps across RDoC domains loaded on the general factor, indicating that maps across distinct studies and tasks showed overlap in activation patterns [27]. ANOVA results indicated significant differences in fit among all the RDoC and data-driven model types (robust RMSEA: F(3, 19588) = 108,961, p < .001; robust CFI: F(3, 19588) = 212,411, p < .001; robust TLI: F(3, 19588) = 209,379, p < .001) [27]. The data-driven bifactor model demonstrated greater overall fit to the data compared with both RDoC models and the data-driven specific factor model (Tukey's test, p < .001) [27].

Comparative Performance of Assessment Approaches

Modern addiction assessment tools show varying degrees of effectiveness across different populations and settings. Digital assessment platforms have demonstrated significant advantages in clinical implementation, with AI-driven tools analyzing electronic health records in real-time and reducing hospital readmissions by 47% [11]. These systems mimic brain-based pattern recognition to identify substance use indicators within clinical documentation, triggering immediate provider alerts when specialist consultations are needed [11].

For adolescent populations, specialized assessment tools have shown particularly strong performance characteristics. The CRAFFT screening tool offers rapid assessment through six targeted questions, while technology-focused instruments like the Internet Addiction Test provide granular analysis of online usage patterns with standardized scoring thresholds (40-69 for addiction, ≥69 for severe cases) ensuring reliable clinical intervention points [11]. The Comprehensive Inventory of Urges and Symptoms (CIUS) employs 5-point Likert scales to capture longitudinal severity patterns from "never" to "very often," while the Internet Severity and Addiction Questionnaire (ISAAQ) uses a 6-point system for more granular assessment of behavioral progression [11].

Table 4: Performance Metrics of Modern Addiction Assessment Tools

| Assessment Tool | Target Population | Administration Time | Key Performance Metrics | Clinical Utility |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| TAPS Tool | Adults | 5-10 minutes | Validated for broad-spectrum screening | Primary care integration, multiple substance assessment |

| CRAFFT 2.1 | Adolescents (12-21) | 2-5 minutes | High sensitivity/specificity for SUD risk | Pediatric settings, early intervention |

| Addiction Severity Index (ASI) | Adults with SUD | 10-20 minutes | 0-9 scoring across 7 domains | Treatment planning, progress monitoring |

| Digital Media Overuse Scale (dMOS) | Technology users | 5-7 minutes | Evaluates 5 online behavior categories | Emerging behavioral addictions |

| Addictions Neuroclinical Assessment | Research populations | Extensive (hours) | Three neurofunctional domains | Precision medicine, mechanism-targeted interventions |

Future Directions: Staging Models and Personalized Intervention

Implementing a Staging Paradigm for Substance Use Disorders

A promising direction for RDoC-aligned addiction research involves the development of comprehensive staging models that incorporate multidimensional factors including social determinants of health [31]. Such models would address the current limitation in which classification systems like DSM-5 diagnose mild, moderate, and severe SUDs based solely on the number of criteria without adequately addressing severity or treatment relevance [31]. A dynamic structured staging model for SUDs could transform clinical care by incorporating the reality of complex psychosocial contributions to patient outcomes [31].