Beyond the Cage: A Modern Framework for Validating Animal Behavior Assays in Human Disorder Modeling

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on the validation of animal behavior assays for modeling human neuropsychiatric disorders.

Beyond the Cage: A Modern Framework for Validating Animal Behavior Assays in Human Disorder Modeling

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on the validation of animal behavior assays for modeling human neuropsychiatric disorders. It explores the foundational concepts of model validity, details methodological applications of common behavioral tests, addresses key challenges in reproducibility and translation, and presents modern frameworks for comparative model assessment. By synthesizing historical perspectives with current technological innovations and standardized validation tools, this resource aims to enhance the reliability and translational value of preclinical behavioral research, ultimately accelerating the development of effective therapeutics.

The Pillars of Validity: Understanding the Historical and Conceptual Foundations

In the pursuit of translating findings from basic animal research to clinical practice, the validity of animal models stands as a cornerstone of psychiatric and neurological drug development. The "triad of validity"—encompassing face, predictive, and construct validity—provides a critical framework for evaluating whether animal behavioral assays accurately model human psychiatric disorders [1] [2]. These criteria determine the extent to which preclinical findings can be meaningfully extrapolated to human conditions, thereby guiding resource allocation in drug development and reducing attrition rates in clinical trials. Within the specific context of animal behavior assays for human disorder modeling, each validity type interrogates a different aspect of the model's relevance: surface-level symptom resemblance (face), response to therapeutic interventions (predictive), and alignment with theoretical underpinnings (construct) [2]. This article deconstructs this triad, providing researchers with a comparative analysis of how these validity types function, their relative strengths and limitations, and their practical application in validating behavioral assays for drug discovery.

Deconstructing the Validity Triad: Definitions and Theoretical Foundations

The triad of validity was formally elaborated by Willner in 1984 and has since become the standard for evaluating animal models of psychiatric disorders [2]. Each component addresses a distinct dimension of the model's utility and biological relevance.

Face Validity is the most straightforward criterion, assessing whether the model appears to measure what it intends to measure based on superficial characteristics. In animal models, this translates to observable behavioral or biological outcomes that resemble the human condition [1]. For instance, anhedonic behavior (a core symptom of depression) in rodents, measured by a decreased preference for sucrose solution, is considered to have high face validity [1] [2]. However, face validity is often considered the weakest form of evidence because it is a subjective assessment based on appearance rather than underlying mechanisms [3] [4].

Predictive Validity evaluates how well performance on a test predicts performance on a criterion measured at a different time [3]. For animal models of psychiatric disorders, this primarily refers to the model's ability to correctly identify treatments that will be therapeutically effective in humans [1] [2]. Willner's original definition specified that a model with high predictive validity should identify pharmacologically diverse antidepressant treatments without making errors of omission or commission, and that potency in the model should correlate with clinical potency [2]. This validity is crucial for drug screening, as it directly impacts the pipeline of candidate compounds moving from preclinical to clinical stages.

Construct Validity is the most complex and theoretically grounded criterion. It assesses how well a test or measurement represents and captures an abstract theoretical concept, known as a construct [4]. A construct refers to an underlying trait (e.g., intelligence, anxiety) that cannot be directly observed but is measured through observable indicators [3] [5]. For an animal model, construct validity requires that the cognitive or biological mechanisms underlying the disorder are identical in both humans and animals [1] [2]. Establishing construct validity is an ongoing process that involves demonstrating the test's relationship with other variables and measures theoretically connected to the construct [4].

Table 1: Core Concepts of the Validity Triad

| Validity Type | Core Question | Key Strength | Primary Limitation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Face Validity | Does the model superficially resemble the human disorder? [2] | Intuitive and easy to assess initially [3] | Subjective; does not guarantee accuracy [4] |

| Predictive Validity | Does the model correctly predict treatment outcomes? [2] | Directly useful for drug screening and development [1] | Can be mechanistic; may not reflect etiology [2] |

| Construct Validity | Does the model accurately represent the theoretical construct? [4] | The most meaningful indicator of a model's true relevance [2] | Difficult and complex to establish fully [4] |

Comparative Analysis: Strengths, Limitations, and Interrelationships

While each validity type offers unique insights, a comprehensive animal model should strive to satisfy all three to maximize its translational value. The table below provides a detailed comparison of the three validity types, highlighting their role in animal behavior assays.

Table 2: Comparative Analysis of the Validity Triad in Animal Behavior Assays

| Aspect | Face Validity | Predictive Validity | Construct Validity |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary Role in Research | Initial, superficial assessment of a model's plausibility [4] | Screening and prioritization of potential therapeutic compounds [2] | Understanding underlying disease mechanisms and etiology [2] |

| Evidence Required | Observable similarity in symptoms (e.g., anhedonia, reduced locomotion) or biomarkers (e.g., elevated corticosterone) [1] | Correlation between treatment effects in the model and known clinical effects in humans [1] [2] | Alignment with theoretical framework; shared biological and cognitive mechanisms [1] [4] |

| Dependence on Other Validity Types | Can exist independently but is weak alone; does not assure predictive or construct validity [4] | Often established independently for drug screening; may not require strong face or construct validity [2] | Considered the overarching form of validity; subsumes aspects of face and predictive validity [6] |

| Risk if Over-Relied Upon | Pursuing superficial symptom mimicry without relevance to the human condition's core pathology [2] | Developing "models" that are merely drug screening tools with no relevance to the human disease state [2] | Becoming mired in theoretical debates, hindering the practical development of useful models [2] |

The relationship between these validities is not always synergistic. A model can have high predictive validity without strong face or construct validity; for example, the Porsolt Forced Swim Test, a common assay for antidepressant activity, has good predictive validity but is often criticized for its poor construct and face validity regarding the human experience of depression [2] [7]. Conversely, a model might have high face validity but fail to predict treatment response. Construct validity is increasingly seen as the most fundamental, as it ensures that the model is truly engaging the neurobiological systems relevant to the human disorder, thereby increasing confidence that findings will translate [2].

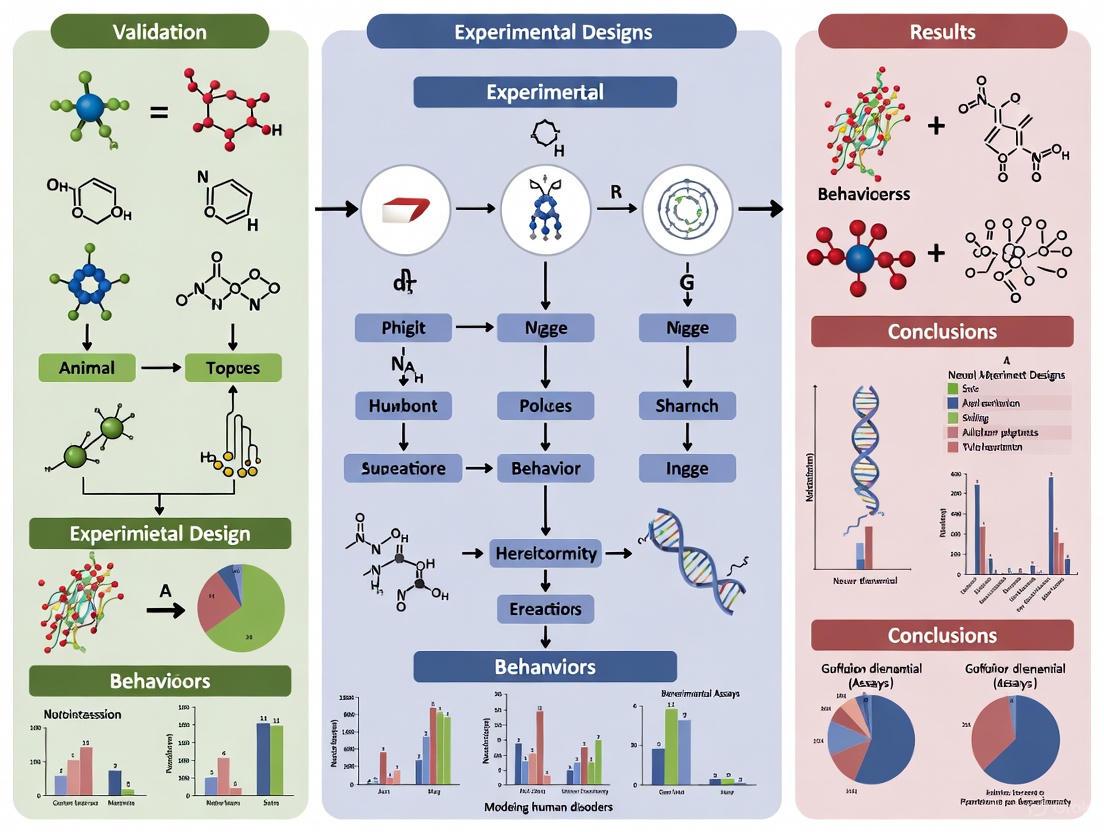

Figure 1: The Interrelationship of Validities in Animal Model Development. Construct validity is foundational, informing and supporting the establishment of face and predictive validity, with the collective goal of improving the model's translational relevance.

Experimental Protocols for Assessing Validity

Establishing the different types of validity requires distinct experimental approaches and protocols. Below are detailed methodologies for key behavioral assays that are central to validation in rodent models.

Assessing Face Validity: The Sucrose Preference Test for Anhedonia

Objective: To measure anhedonia, a core symptom of depression, by quantifying a rodent's inherent preference for a sweet-tasting sucrose solution over plain water [1] [2].

Protocol:

- Habituation: Animals are first habituated to the presence of two drinking bottles in their home cage, both containing plain water, for 48 hours.

- Water Deprivation: Following habituation, animals are mildly water-deprived for a short period (e.g., 4-18 hours) to ensure sufficient drinking motivation.

- Test Session: The two bottles are replaced—one with a 1-2% sucrose solution and the other with plain water. The positions of the bottles are counterbalanced between subjects to control for side preferences.

- Measurement: The animals are given free access to both bottles for a defined period (typically 1-24 hours). The consumption of sucrose solution and water is measured by weighing the bottles before and after the test.

- Calculation: Sucrose preference is calculated as: (Sucrose intake / Total fluid intake) × 100%. A significant reduction in this percentage in a test group compared to a control group is interpreted as anhedonic behavior, providing face validity for depression-like states.

Assessing Predictive Validity: The Elevated Plus Maze for Anxiety

Objective: To evaluate the anxiolytic (anxiety-reducing) effects of compounds by exploiting the natural conflict between a rodent's tendency to explore novel environments and its innate fear of open, elevated spaces [7].

Protocol:

- Apparatus: The maze consists of a plus-shaped platform elevated above the floor. It has two open arms (without walls) and two closed arms (with high walls), all connected by a central square.

- Pre-Test Handling: Animals are handled regularly for several days prior to testing to minimize stress.

- Test Session: The subject is placed in the central square, facing an open arm. Its behavior is recorded for a standard duration (e.g., 5 minutes).

- Key Behavioral Measures:

- Time spent in the open arms vs. closed arms.

- Number of entries into the open arms vs. closed arms.

- Risk-assessment behaviors (e.g., stretch-attend postures) at the entrance to the open arms.

- Validation: Anxiolytic drugs (e.g., benzodiazepines) are known to increase the proportion of time spent and number of entries into the open arms. A test compound that produces a similar behavioral profile demonstrates the assay's predictive validity for anxiolytic action [7].

Assessing Construct Validity: Fear Conditioning for Anxiety and Memory

Objective: To model the formation and expression of associative emotional memory, relevant to anxiety disorders (e.g., PTSD), by pairing a neutral stimulus with an aversive one [7].

Protocol:

- Apparatus: A specialized chamber with a grid floor for delivering mild foot shocks and features for presenting a conditioned stimulus (CS), such as a light or tone.

- Acquisition (Day 1): The animal is placed in the chamber. After a habituation period, a neutral CS (e.g., a 30-second tone) is presented, which coterminates with a mild, aversive unconditioned stimulus (US), such as a 1-second foot shock. This pairing is repeated several times.

- Contextual Memory Test (Day 2): The animal is placed back into the same chamber without any tone or shock. The amount of time spent freezing (a species-typical fear response) is measured. Freezing in this context indicates learning of the association between the environment (context) and the shock.

- Cued Memory Test (Day 2, later): The animal is placed in a novel, distinctly different chamber. After a habituation period, the CS (tone) is presented in the absence of the shock. Freezing during the tone presentation indicates learning of the association between the discrete cue and the shock.

- Construct Validation: This assay has strong construct validity because the neurocircuitry underlying this form of learning (heavily dependent on the amygdala and hippocampus) is highly conserved between rodents and humans, and the cognitive process of associative learning is directly relevant to the etiology of certain anxiety disorders [7].

Figure 2: Fear Conditioning Workflow for Construct Validity. This two-day protocol assesses the formation and expression of associative fear memory, tapping into specific, conserved neural circuits to provide strong construct validity for anxiety and memory disorders.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

The following table details key reagents, equipment, and software solutions essential for conducting and analyzing the behavioral assays discussed in this article.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions for Behavioral Assays

| Item Name | Specific Function | Application in Validity Assessment |

|---|---|---|

| Sucrose Solution (1-2%) | Serves as a hedonic stimulus to quantify anhedonia via consumption preference. | Core reagent for the Sucrose Preference Test, used to establish face validity for depression models [1]. |

| EthoVision XT Tracking Software | Automated video tracking system that quantifies locomotor activity, time in zones, and complex behaviors. | Used across multiple assays (Open Field, EPM, MWM) to provide objective, high-throughput behavioral data for face, predictive, and construct validity [7]. |

| Elevated Plus Maze Apparatus | Creates an approach-avoidance conflict; used to measure anxiety-like behavior based on time in open vs. closed arms. | Standard equipment for screening anxiolytic drugs, central to establishing predictive validity [7]. |

| Fear Conditioning Chamber | Controlled environment for administering precise conditioned (tone/light) and unconditioned (mild foot shock) stimuli. | Foundational apparatus for studying associative learning and memory, providing robust construct validity for anxiety and PTSD models [7]. |

| Morris Water Maze Pool | Apparatus for testing spatial learning and memory by requiring animals to find a submerged hidden platform using distal cues. | Key test for hippocampal-dependent learning, used to assess cognitive deficits and construct validity in models of neurodegenerative disorders [7]. |

| Known Psychoactive Compounds (e.g., Benzodiazepines, SSRIs) | Gold-standard therapeutics used as positive controls to verify that an assay responds to clinically effective treatments. | Critical for establishing predictive validity in any behavioral model intended for drug discovery [2]. |

| Rotarod Apparatus | Measures motor coordination and balance by testing the animal's ability to stay on a rotating rod. | Control assay to rule out motor deficits that could confound interpretation of primary behavioral tests, supporting internal validity [7]. |

The triad of face, predictive, and construct validity provides an indispensable, multi-faceted framework for deconstructing and evaluating animal behavior assays in psychiatric research. While face validity offers an intuitive check for symptom mimicry and predictive validity is paramount for efficient drug screening, construct validity remains the most rigorous standard for ensuring a model's true relevance to human disease mechanisms. A model strong in all three areas offers the greatest promise for translational success. As the field advances, with emerging technologies like artificial intelligence beginning to augment behavioral analysis [8], these core validity principles will continue to guide the development of more refined, reliable, and human-relevant animal models, ultimately accelerating the discovery of novel therapeutics for psychiatric and neurological disorders.

The development of effective treatments for human psychiatric disorders relies heavily on the availability of preclinical animal models that accurately recapitulate aspects of human disease. The value of these models is determined by specific validation criteria that have evolved significantly over the past half-century. This progression reflects the scientific community's deepening understanding of disease complexity and a growing emphasis on translational relevance. The validation framework began with relatively simple, pragmatic checklists and matured into a sophisticated, multi-dimensional system for evaluating how well animal models predict human therapeutic outcomes. Understanding this evolutionary pathway—from the initial criteria proposed by McKinney and Bunney to the widely adopted Willner framework and subsequent refinements—is essential for researchers designing robust experiments and accurately interpreting preclinical data in the context of human psychiatric conditions such as depression and anxiety [9] [10].

This guide objectively compares these foundational validation frameworks, providing researchers with a clear reference for evaluating animal models in their own work. The subsequent sections will detail the historical development, compare the core criteria, present experimental case studies, and outline contemporary methodological best practices.

Historical Development of Validation Criteria

The conceptual framework for validating animal models has shifted from a primary focus on internal consistency and pragmatic drug screening toward a greater emphasis on external and translational validity.

The Initial Framework: McKinney & Bunney (1969)

McKinney and Bunney were the first to formally propose criteria focused on the external validity of animal models, specifically for affective disorders. Their original paper outlined five key requirements for an animal model, which later literature often condenses and summarizes as focusing on four main areas [9] [10]:

- Similarity of Symptoms (Analogous Symptoms): The animal model should display behavioral changes analogous to human symptoms.

- Observable and Measurable Behavioral Changes: The behaviors must be quantifiable and consistent.

- Similar Response to Treatments: Effective treatments in humans should also be effective in the model.

- Biological Similarity: This includes similarities in etiology and underlying biochemistry, though these were not as explicitly detailed in their original list as commonly believed [9].

The Consolidation: Willner's Triadic Criteria (1984)

In 1984, Paul Willner simplified and restructured the existing ideas into a triad of validity criteria that have become the standard in the field. This framework drew inspiration from psychological validation concepts proposed earlier by Cronbach and Meehl. Willner's three criteria are [9] [10]:

- Predictive Validity: The model's ability to correctly identify therapeutic treatments.

- Face Validity: The phenomenological similarity of the model's manifestations to the human condition (symptoms).

- Construct Validity: The theoretical rationale behind the model—how well the model reflects the underlying theoretical constructs of the human disorder.

Modern Refinements: Belzung & Lemoine (2011)

Responding to the limitations of Willner's framework, Belzung and Lemoine proposed a more granular set of five criteria to better align with modern, multifactorial disease concepts like the diathesis model of depression [9]:

- Homological Validity: Appropriateness of the species and strain used.

- Pathogenic Validity: Similarity in the factors that trigger the disorder.

- Mechanistic Validity: Identity of the underlying biological and cognitive mechanisms.

- Face Validity: Similarity in observable behavioral and biological outcomes.

- Predictive Validity: Identity in the relationship between triggers/treatments and outcomes.

Table 1: Chronological Evolution of Animal Model Validation Criteria

| Timeline | Proponent(s) | Core Criteria | Primary Focus and Advancement |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1969 | McKinney & Bunney | • Similarity of Symptoms• Observable/Measurable Behavior• Similar Response to Treatments• Biological Similarity | Established the first structured set of external validity criteria, moving beyond simple pragmatic screens [9]. |

| 1984 | Willner | • Predictive Validity• Face Validity• Construct Validity | Consolidated prior concepts into a seminal, simplified tripartite framework that became the field standard [9] [10]. |

| 2011 | Belzung & Lemoine | • Homological Validity• Pathogenic Validity• Mechanistic Validity• Face Validity• Predictive Validity | Refined and expanded the criteria into a more nuanced, multi-factorial set to better capture complex disorder etiology [9]. |

Comparative Analysis of Core Validation Criteria

The following table provides a detailed comparison of the three main validation frameworks, highlighting their definitions, key components, and associated challenges.

Table 2: Detailed Comparison of Core Validation Criteria Across Frameworks

| Criterion | Definition & Key Aspects | McKinney & Bunney (1969) | Willner (1984) | Belzung & Lemoine (2011) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Predictive Validity | Definition: The model's ability to predict unknown aspects of the human condition, particularly therapeutic response. | Similar Response to Treatments: Focused on the model's correct identification of known effective therapies [9]. | Core Criterion: Explicitly defined as the ability to identify antidepressant treatments accurately [9]. | Subdivided into: • Induction Validity: Link between trigger and outcome.• Remission Validity: Effects of treatments [9]. |

| Challenges: A model with high predictive validity may lack mechanistic insight [10]. | ||||

| Face Validity | Definition: The superficial, phenomenological similarity between the model and the human disorder. | Analogous Symptoms: Explicitly included the need for symptom similarity in the model [9]. | Core Criterion: Similarity in symptoms between the animal model and the human condition [10]. | Subdivided into: • Ethological Validity: Observable behaviors (e.g., anhedonia).• Biomarker Validity: Biological measures (e.g., elevated corticosterone) [9]. |

| Challenges: Relies on surface-level comparisons; human psychiatric symptoms can be difficult to assess in animals [9]. | ||||

| Construct Validity | Definition: How well the model reflects the theoretical construct and known etiology of the human disorder. | Implied in "Cause": Similarity of cause was mentioned, but not as a fully developed criterion [9]. | Core Criterion: The theoretical rationale for the model—whether the mechanisms inducing the state in animals are analogous to those in humans [9] [10]. | Expanded into three criteria: • Homological Validity (Species/Strain)• Pathogenic Validity (Ontopathogenic/Triggering)• Mechanistic Validity (Biological/Cognitive mechanisms) [9]. |

| Challenges: Requires a well-understood and agreed-upon disease etiology, which is often lacking in psychiatry [9]. |

Diagram 1: The evolution of validation criteria from broad foundations to a consolidated triad and finally a detailed multifactorial system.

Experimental Validation: A Case Study in Depression Models

To illustrate the application of these validity criteria, we examine a direct comparative study of two rodent models of depression: the well-established Chronic Mild Stress (CMS) model and a newer Ultrasound-Induced (US) model [11].

Experimental Protocol and Methodologies

This study employed a standardized comparison of the CMS and US models in male Wistar rats (n=60). The detailed protocols were as follows [11]:

- Chronic Mild Stress (CMS) Protocol: Rats were exposed to a 3-week schedule of unpredictable, mild stressors. The protocol included periods of food deprivation, water deprivation, intermittent lighting, cage tilting, stroboscopic illumination, and housing in soiled cages or with unfamiliar partners. This variability prevents habituation and is a key feature of the CMS paradigm [11].

- Ultrasound-Induced (US) Protocol: Rats were continuously exposed for 3 weeks to variable-frequency ultrasound (20–45 kHz) at 50 ± 5 dB. The frequencies changed unpredictably every 10 minutes, simulating a state of "informational uncertainty" or a negative information flow, which is posited to mimic a core aspect of human psychological stress [11].

- Behavioral and Biological Endpoints: One day post-stress, animals underwent a battery of tests in this sequence: sucrose preference test (for anhedonia), social interest test, open field test, forced swim test (for behavioral despair), and the Morris water maze (for cognitive function). Plasma levels of corticosterone, epinephrine, norepinephrine, and dopamine were also measured [11].

Quantitative Results and Validity Assessment

The data from this comparative study were used to assess each model against the three primary validity criteria.

Table 3: Experimental Data Comparison: CMS vs. Ultrasound-Induced Model

| Test / Measure | Chronic Mild Stress (CMS) Model Outcomes | Ultrasound-Induced (US) Model Outcomes | Implication for Validity |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sucrose Preference | Decreased preference, indicating anhedonia [11]. | More pronounced decrease in preference, indicating stronger anhedonia [11]. | Face Validity: Anhedonia is a core symptom of depression. Both models show face validity, with the US model showing a stronger effect [11]. |

| Social Interaction Test | Reduced social interaction [11]. | More pronounced social isolation [11]. | Face Validity: Social withdrawal is a key symptom. The US model produced a more pronounced effect [11]. |

| Forced Swim Test | Increased immobility time [11]. | Increased immobility time [11]. | Face/Predictive Validity: Behavioral despair is a common endpoint; reversal by antidepressants confers predictive validity [11]. |

| Hormone & Neurotransmitter Levels | Dysregulation of the HPA axis and monoamines is known from literature. | Increased corticosterone, epinephrine, norepinephrine; reduced dopamine [11]. | Construct Validity: These biological changes mirror those seen in human depression, supporting the construct validity of both, and specifically demonstrated for the US model [11]. |

| Antidepressant Response | Reversal of behavioral deficits by known antidepressants (from established literature) [11]. | Reversal of behavioral deficits by various antidepressant classes [11]. | Predictive Validity: The ability to detect efficacy of standard treatments is a cornerstone of predictive validity. Both models demonstrate this [11]. |

The study concluded that while the established CMS model is valid, the novel US model is also suitable and meets all three required validity criteria, in some behavioral domains (anhedonia, social isolation) producing even more pronounced effects [11].

Essential Methodologies for Contemporary Behavioral Assays

Modern validation of animal models extends beyond theoretical criteria to incorporate rigorous methodological standards that ensure reliability and reproducibility.

The Pillars of Reproducible Experimental Design

To minimize bias and environmental variables, well-conceived behavioral experiments must adhere to several key principles [12]:

- Blinding: The technician conducting behavioral evaluations and analysis should be unaware of the treatment groups. If blinding is impossible due to visual cues, an independent technician should perform the final data interpretation [12].

- Randomization and Counterbalancing: Test subjects must be randomly assigned to treatment groups. When baseline testing is involved, groups should be counterbalanced for performance levels and body weight to avoid bias. The order of testing across days and apparatuses must also be randomized [12].

- Appropriate Controls: Vehicle control groups are essential and must be treated identically to the test compound group, including matching formulation excipients and injection procedures, to control for handling-induced stress [12].

- Sample Size Justification: Group sizes of 10-20 per sex per treatment are typically required to achieve statistical power. Small, underpowered pilot studies can be used for power calculations but should be confirmed in a second, independently powered cohort. Sexes should not be combined without statistical justification [12].

Technological Advances in Behavioral Data Capture

The move from manual observation to automated, computer-based systems has significantly improved the objectivity, throughput, and depth of behavioral analysis.

- Automated Video Tracking Systems: Software like EthoVision XT, AnyMaze, and TopScan uses pattern analysis of video images to extract quantitative measurements of animal behavior, such as location, distance traveled, and speed [13]. These systems are superior for measuring brief behaviors, long-duration activities, and precise spatial measurements that are difficult for human observers to estimate accurately [13].

- Custom and Open-Source Solutions: While commercial software is common, there is a growing demand for cost-effective and user-friendly alternatives. The development of in-house software, such as the Advanced Move Tracker (AMT), demonstrates the ability to produce data that correlates highly with both manual observation and commercial systems, providing a valid and accessible tool for researchers [13].

- Bio-logger Validation: For studies using wearable activity loggers on animals, validation is critical. A simulation-based methodology using synchronized video and raw sensor data allows researchers to validate data collection strategies (like intermittent sampling or data summarization) before deploying loggers in the field, ensuring the reliability of the inferred behavioral data [14].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 4: Key Reagents and Materials for Behavioral Validation Experiments

| Item Category | Specific Examples | Function in Validation |

|---|---|---|

| Animal Models | Wistar rats, C57BL/6 mice, Transgenic lines (e.g., Smn1/hSmn2 for SMA). | Subject for behavioral phenotyping. Strain/species choice is part of homological validity [10] [11] [13]. |

| Pharmacologic Agents | Diazepam (anxiolytic), Known Antidepressants (e.g., Imipramine, Fluoxetine), Test Compounds. | Positive controls for predictive validity (e.g., demonstrating an anxiolytic effect) and for testing novel treatments [12] [11]. |

| Hormone/Neurotransmitter Assay Kits | Corticosterone ELISA, Catecholamine (Epinephrine, Norepinephrine, Dopamine) ELISA/HPLC kits. | To measure biomarker-level changes for construct and face validity (biomarker validity) [9] [11]. |

| Automated Tracking Software | EthoVision XT (Noldus), AnyMaze, TopScan, Custom solutions (e.g., Advanced Move Tracker). | To provide objective, high-throughput, and reliable quantification of animal behavior, minimizing observer bias and fatigue [13]. |

| Specialized Behavioral Equipment | Sucrose Dispensers, Open Field Arenas, Elevated Plus Mazes, Forced Swim Tanks, Morris Water Maze. | To conduct standardized tests that operationalize and measure specific behavioral domains relevant to the human disorder (face validity) [11] [13]. |

Diagram 2: A modern workflow for validating animal behavior assays, integrating rigorous experimental design, technical proficiency, and advanced technology.

The field of psychiatric research is undergoing a fundamental transformation in how mental disorders are conceptualized and studied. For decades, the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM) and International Classification of Diseases (ICD) framework has dominated psychiatric classification and research, operating on a neo-Kraepelinian assumption that mental disorders represent largely discrete entities characterized by distinctive signs, symptoms, and natural histories [15]. This DSM-ICD approach adopts an Aristotelian model of categorization, presuming that psychiatric disorders differ qualitatively from both normality and from each other [15]. While this system has provided a common language for clinicians and researchers and has demonstrated some treatment validity through the development of empirically supported therapies for specific disorders, growing anomalies within the DSM-ICD system have prompted a scientific reevaluation [15].

In response to these limitations, the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) launched the Research Domain Criteria (RDoC) initiative, which embraces a Galilean view of psychopathology as the product of dysfunctions in neural circuitry [15]. Central to this new approach is the concept of the endophenotype – heritable, quantifiable intermediate behavioral phenotypes that serve as a causal link between genes and observable symptoms in neuropsychiatric and neurological disorders [16]. This paradigm shift represents more than just a change in terminology; it constitutes a fundamental restructuring of how researchers conceptualize, measure, and investigate mental disorders, with profound implications for animal model development and validation in preclinical research.

Defining the Paradigms: Core Concepts and Criteria

The DSM-ICD Syndrome Approach

The DSM-ICD framework has served as the overarching model of psychiatric classification since at least the middle of the past century. This system is fundamentally syndromic, focusing on clinical symptom clusters that co-occur in ways that suggest underlying disorders. The approach emphasizes the differentiation of conditions based on their signs, symptoms, and natural history, providing standardized diagnostic criteria and algorithms for each diagnosis [15]. This model facilitated improved inter-rater reliability and created a common diagnostic language, but it suffers from significant limitations for research purposes, including heterogeneity within diagnostic categories, symptom overlap between disorders, and a lack of clear connection to underlying biological mechanisms [17] [15].

The Endophenotype Approach

Endophenotypes are defined as measurable components along the pathway between genotype and disease, requiring special processes or instruments for detection [16]. They can include neurophysiological, biochemical, endocrinological, neuroanatomical, cognitive, or neuropsychological measures and are believed to have a closer relationship to the underlying disease genotype than broader syndromic classifications [16]. The concept was originally introduced in psychiatry by Gottesman and Shields in the early 1970s to address the challenge of linking genes to complex psychiatric conditions by dividing behavioral symptoms into more stable phenotypes [16].

Table 1: Validation Criteria for Endophenotypes

| Criterion | Description | Research Application |

|---|---|---|

| Association with Illness | The endophenotype must be associated with the illness in the population | Serves as a measurable indicator linked to the disorder of interest |

| Heritability | The endophenotype must be heritable | Indicates a genetic component that can be systematically studied |

| State Independence | Manifest whether illness is active or in remission | Not merely an episode-dependent symptom but a stable trait |

| Familial Co-segregation | Co-segregates with illness within families | Higher prevalence in unaffected relatives of probands than in general population |

| Reliable Measurement | Amenable to reliable quantification and specific to illness | Provides objective, reproducible metrics for research |

Rigorous criteria define true endophenotypes, including association with illness, heritability, state independence (manifesting whether illness is active or in remission), co-segregation within families, and reliable measurement [18] [16]. These traits can be present in both affected individuals and their unaffected relatives, reflecting dimensional behavioral variation and genetic risk independent of actual disease manifestation [16]. This characteristic makes them particularly valuable for genetic studies and for investigating vulnerability mechanisms.

Comparative Analysis: Paradigm Strengths and Limitations

Table 2: DSM-Syndromic vs. Endophenotype Model Comparison

| Feature | DSM-Syndromic Model | Endophenotype Model |

|---|---|---|

| Classification Basis | Clinical symptom clusters | Neurobiological, cognitive, and neurophysiological measures |

| Genetic Connection | Indirect and heterogeneous | Direct, closer to genetic underpinnings |

| Measurement Approach | Clinical observation and patient report | Laboratory-based quantitative measures |

| Disorder Boundaries | Categorical divisions | Dimensional, often transdiagnostic |

| Research Utility | High clinical face validity, but heterogeneous groupings | Reduced heterogeneity, increased statistical power for genetic studies |

| Primary Limitations | Comorbidity, diagnostic overlap, biological heterogeneity | May not capture full clinical syndrome, requires specialized assessment |

The shift from DSM syndromes to endophenotypes addresses several fundamental challenges in psychiatric research. The endophenotype approach reduces heterogeneity by dissecting complex neurobiological traits and disorders into more elementary, quantifiable components [16]. This decomposition provides more direct links to biological pathways and increases statistical power in genetic studies by working with phenotypes closer to the gene effects [16]. Furthermore, endophenotypes facilitate translational research through cross-species compatibility, as many neurophysiological and cognitive measures can be assessed in both humans and animal models [16] [17].

However, the endophenotype approach is not without limitations. The lack of diagnostic specificity makes endophenotypes easier to detect but non-diagnostic [16]. Many endophenotypes are shared across various neuropsychiatric disorders, and boundaries between disorders dissolve when using an endophenotype approach [16]. This transdiagnostic characteristic enhances biological validity but complicates clinical application. Additionally, establishing endophenotypes requires rigorous validation, including longitudinal and family-based studies to establish trait stability and familial co-segregation [16].

Experimental Validation: Behavioral Assays and Their Neural Correlates

The validation of animal models in neuroscience requires a multidisciplinary approach with careful consideration of scientific criteria including replicability/reliability, predictive validity, construct validity, and external validity/generalizability [17]. Animal models are defined as living organisms used to study brain-behavior relations under controlled conditions, with the final goal of enabling predictions about these relations in humans [17]. The endophenotype approach facilitates this process by focusing on elemental phenotypes that are observable, measurable, and testable in both humans and animals [17].

Table 3: Representative Behavioral Assays for Key Endophenotypes

| Behavioral Assay | Measured Endophenotype | Neural Substrates | Translational Relevance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Prepulse Inhibition (PPI) | Sensorimotor gating | Complex brainstem-mediated reflex pathways | Schizophrenia, major depression |

| Morris Water Maze | Spatial navigation, reference memory | Hippocampus, entorhinal cortex | Alzheimer's disease, cognitive aging |

| Novel Object Recognition | Recognition memory | Dorsal hippocampus | Cognitive deficits across disorders |

| Conditioned Freezing | Fear conditioning, emotional memory | Amygdala (cued), hippocampus (contextual) | Anxiety disorders, PTSD |

| Social Preference Test | Sociability, social novelty | Multiple systems including prefrontal circuits | Autism spectrum disorder models |

| 5-Choice Serial Reaction Time | Attention, impulsivity, executive function | Prefrontal-striatal circuits | ADHD, cognitive control deficits |

Methodological Protocols for Key Behavioral Assays

Prepulse Inhibition (PPI) Protocol: PPI is an established method for testing sensorimotor gating that is abnormal in conditions such as schizophrenia [19]. The assay measures the reduction in startle response when a startling stimulus is preceded by a weaker, non-startling stimulus (prepulse). The acoustic startle response (ASR) and tactile startle reflex (TSR) evaluate complex brainstem-mediated reflex pathways [19]. Responses are similar in humans and rodents, offering homologous cross-species comparability [19]. Experimental sessions typically consist of multiple trial types including pulse-alone trials, prepulse-pulse trials, and no-stimulus trials, with startle magnitude measured using specialized equipment.

Morris Water Maze Protocol: This is the most widely used test for measuring spatial navigation and reference memory [19]. The animal is placed in an open, circular pool of room temperature water with a submerged platform. Over a series of trials, the animal learns to use distal cues located outside the maze to spatially navigate to the platform despite being placed in the maze at different starting positions [19]. Mice typically require a one-day training session to swim to a visible platform, followed by 5 days of learning to navigate to a hidden platform [19]. Rats typically do not require the initial training day. A probe trial with the platform removed assesses reference memory. The test relies on an intact hippocampus and entorhinal cortex [19].

Novel Object Recognition Protocol: This test uses the animal's reaction to a novel object within the context of familiar objects as a test of recognition memory [19]. First, the animal is familiarized with two or four identical objects. After a predetermined interval (which can be varied to test different memory retention periods), it is placed back in the test chamber with identical copies of the original objects and one new object [19]. Time spent exploring the novel object in preference to the familiar objects reflects memory of what has changed. This test is mediated by the dorsal hippocampus [19] and provides a measure of recognition memory that is translatable across species.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions

Table 4: Essential Research Materials for Endophenotype Investigation

| Research Tool Category | Specific Examples | Primary Research Application |

|---|---|---|

| Behavioral Apparatus | Acoustic startle chambers, Morris water maze, elevated zero maze, operant conditioning chambers | Quantitative assessment of specific behavioral endophenotypes |

| Pharmacological Agents | Indirect dopaminergic agonists, selective dopamine D1/D2 agonists/antagonists, cholinergic-muscarinic antagonists, glutamatergic-NMDA receptor antagonists | Manipulation of specific neurotransmitter systems to probe neural mechanisms |

| Video Tracking Systems | AnyMaze, EthoVision, custom SAS analysis programs [19] | Automated, objective behavioral quantification with minimal observer bias |

| Genetic Modification Tools | CRISPR-Cas9, transgenic animal models, selective breeding protocols | Investigation of genetic contributions to endophenotype expression |

| Neurophysiological Recording | EEG/ERP systems, in vivo electrophysiology, photometry systems | Direct measurement of neural activity correlates of behavioral endophenotypes |

The investigation of endophenotypes requires specialized research tools and approaches. Behavioral apparatus forms the foundation for endophenotype assessment, with specific tasks designed to measure particular neurobehavioral domains [19]. Pharmacological challenges are frequently employed to probe neurotransmitter systems involved in endophenotype expression, using targeted agonists and antagonists to temporarily alter neural function [19]. Advanced video tracking systems with associated analysis software enable precise, automated behavioral quantification that minimizes observer bias and enhances reproducibility [19]. Genetic manipulation tools allow researchers to investigate specific genetic contributions to endophenotypes, creating models with particular genetic variations associated with human disorders. Finally, neurophysiological recording techniques provide direct measures of neural activity that correlate with behavioral endophenotypes, bridging the gap between brain function and behavior.

Visualizing the Paradigm Shift: Conceptual Framework

Conceptual Framework of the Modeling Paradigm Shift

The diagram illustrates the fundamental differences between the traditional DSM-ICD syndrome model and the emerging endophenotype approach. The DSM model (red) begins with clinical symptom clusters as its foundation, which leads to challenges with heterogeneity and symptom overlap between disorders. In contrast, the endophenotype model (blue) is grounded in biological mechanisms, quantitative measures, and cross-species compatibility. Genetic risk factors (green) directly influence multiple categories of endophenotypes, including neurophysiological, cognitive, and neuroanatomical measures, which collectively contribute to the comprehensive endophenotype model. The dashed yellow arrow represents the paradigm shift from syndrome-focused to mechanism-focused approaches in psychiatric research.

The shift from DSM syndromes to endophenotypes represents more than a theoretical debate – it has practical implications for how researchers design studies, select animal models, and develop new therapeutics. This paradigm transition supports a more mechanistic approach to psychiatric research that emphasizes understanding the neurobiological pathways between genetic vulnerability and behavioral expression. The endophenotype approach facilitates the development of animal models with stronger translational validity by focusing on conserved biological and behavioral mechanisms that can be reliably measured across species [17].

For drug development professionals, this shift offers the potential for target engagement biomarkers that can guide early-stage clinical trials and help identify patient subgroups most likely to respond to specific mechanisms of action. The RDoC framework, which incorporates endophenotypes, aims to classify disorders based on biological and psychosocial features rather than clinical diagnosis alone, promoting integration from genes to neural systems to behavior [16]. As this paradigm continues to evolve, it promises to enhance the precision and efficacy of both basic research and therapeutic development in psychiatry and neurology.

Behavioral assays represent a cornerstone of preclinical neuroscience research, providing critical tools for investigating neuropsychiatric disorders, cognitive functions, and therapeutic interventions. These systematic procedures enable researchers to quantify behavioral responses in model organisms, bridging the gap between biological mechanisms and complex behavioral phenotypes. As the field moves toward dimensional approaches that focus on specific symptom clusters rather than attempting to model entire complex syndromes, the optimization and validation of these assays become increasingly important for translational success. This review examines the fundamental principles, applications, and methodological considerations of behavioral assays in neuroscience research, with particular emphasis on their validation for modeling human disorders and evaluating novel therapeutic agents. We compare established behavioral paradigms, detail experimental protocols, and provide a framework for assay implementation that ensures reliability and reproducibility across laboratories.

Behavioral assays are systematic procedures used in neuroscience to qualitatively assess and quantitatively measure specific behavioral responses in model organisms. Unlike chemical assays that detect substances or bioassays that measure biological activity, behavioral bioassays utilize whole-animal behavior as the primary readout, enabling researchers to investigate complex neurobiological processes, cognitive functions, and emotional states [20]. These tools are indispensable for preclinical investigation of neuropsychiatric disorders, where knowledge of underlying neurobiology often remains incomplete, making validation of animal models particularly challenging [21].

The fundamental purpose of behavioral assays in neuroscience extends beyond mere observation to answering specific questions about animal and human behavior. As outlined by Tinbergen's four categories, these questions span ontogeny (development), mechanism (causation), adaptive significance (function), and evolution [20]. In practice, this means behavioral assays allow researchers to address diverse questions such as how neural circuits generate specific behaviors, how genes and environment interact to shape behavioral outputs, and how pathological states alter normal behavioral patterns. The growing importance of testing novel CNS concepts and neuroactive drugs has spurred continued refinement of existing behavioral tests and the development of new assay paradigms [22].

In contemporary neuroscience research, there is an emerging trend toward dimensional approaches that define limited behavioral dimensions accounting for clusters of symptoms that co-vary within and across psychiatric illnesses. Rather than attempting to develop animal models that emulate all aspects of complex human neuropsychiatric syndromes such as depression, this approach focuses on modeling specific components or dimensions of an illness, representing specific symptom clusters that may share common underlying neurobiological mechanisms [21]. This methodological shift has increased the precision of behavioral assays while enhancing their translational relevance for understanding human disorders.

Fundamental Principles and Classification of Behavioral Assays

Defining Characteristics and Assay Types

Behavioral assays in neuroscience share common characteristics with other scientific assays, requiring standardized procedures, specific apparatuses, methods for detecting and quantifying variables of interest, and controls for confounding variables [20]. Three primary types of assays are utilized in neuroscience research: chemical assays that detect specific substances, bioassays that measure biological activity in response to specific stimuli, and behavioral bioassays that use whole-animal behavior as the measurement output. Behavioral bioassays may be further categorized based on their application for detecting external stimuli (such as environmental toxins or pheromones) or internal stimuli (such as hormones, drugs, neurochemicals, or disease processes) [20].

The design and implementation of behavioral bioassays require careful consideration of multiple factors: which specific behaviors to study, how to define behavioral units that serve as the assay's foundation, when to sample behavior, and how to record and analyze the resulting data [20]. Well-conceived behavioral assays must be reproducible and account for environmental variables while eliminating potential bias through key principles including blinding, randomization, counterbalancing, appropriate sample sizes, and inclusion of proper controls [12].

Pillars of Reproducibility

Reproducibility stands as a critical concern in behavioral neuroscience, with several methodological pillars essential for reliable data generation:

Blinding: At minimum, technicians responsible for behavioral evaluation and data analysis should be unaware of treatment groups. When visual clues make blinding challenging, independent technicians should perform analysis and interpretation before treatment codes are revealed [12].

Randomization and Counterbalancing: Test subjects must be randomly assigned to treatment groups, with considerations for counterbalancing performance levels and body weights evenly across groups. This principle extends to testing sessions, time of day, multiple testing equipment, and treatments within group-housed cages [12].

Controls: Vehicle controls should always be included in experimental designs, receiving identical treatment except for the test compound. This practice ensures that injection-related stress or handling effects don't confound interpretation of results [12].

Sample Size: Group sizes of 10-20 per sex per genotype/treatment typically represent minimal sample sizes required to achieve statistical significance in behavioral assays based on previous power analyses. Combining small sample sizes from separate experiments is methodologically inappropriate, though pilot data from small cohorts can inform power calculations for follow-up experiments [12].

Table 1: Key Methodological Principles for Behavioral Assay Validation

| Principle | Implementation Guidelines | Impact on Data Quality |

|---|---|---|

| Blinding | Technician unaware of treatment groups; independent analysis if visual cues present | Reduces observer bias in behavioral scoring and data interpretation |

| Randomization | Random assignment to groups; counterbalancing of performance levels across treatments | Minimizes systematic bias and ensures group comparability |

| Environmental Control | Minimize noise/vibration; consistent lighting, temperature, and humidity | Reduces external variables affecting behavioral responses |

| Technical Proficiency | Demonstrate ability to reproduce published data sets with positive controls | Ensures reliable assay execution and data collection |

| Appropriate Controls | Vehicle controls; wild-type controls in phenotyping experiments | Ispecific treatment effects from procedural artifacts |

Methodological Optimization of Behavioral Assays

Environmental and Technical Considerations

The behavioral testing environment requires careful optimization beyond simply placing equipment in available laboratory space. The testing environment must be sufficiently sensitive to detect expected behavioral outcomes, necessitating avoidance of high-traffic areas, elevator shafts, restroom facilities, or cage wash facilities to minimize disruptions from noise and vibration [12]. documented that high vibration levels can impact breeding and pup survival, suggesting similar potential effects on behavioral responses [12]. A consistent and rigorously controlled procedure space represents a major factor in achieving reliable, reproducible behavioral data.

Technical proficiency stands as another critical component in behavioral assay optimization. Researchers should demonstrate mastery of sensitive behavioral tests by reproducing published data sets with test compounds or established mouse models serving as positive controls [12]. This proficiency testing should be conducted with technicians blind to treatment groups or genotypes to eliminate potential bias and provide confidence in their technical capabilities. Failure to reproduce positive control data when all variables are known should caution investigators that their assay system requires further optimization before testing experimental unknowns [12].

Assay Validation and Positive Controls

The "great equalizer" across often uncontroll laboratory variables is demonstrating that a behavioral test possesses sufficient sensitivity to detect expected behavioral changes through proper validation [12]. Before testing experimental unknowns, initial experiments should establish the assay's ability to produce expected baseline results when positive or known standards are evaluated. For example, when establishing an assay sensitive to anxiolytic effects, technicians should demonstrate that a standard anxiolytic agent (e.g., diazepam) produces the expected anxiolytic-like effect [12]. This validation approach provides confidence that the test conducts under optimal conditions, distinguishing true negative results from methodological failures.

This validation principle should not be confused with expecting novel mechanisms of action to produce identical behavioral effects as known standards. Rather, it provides confidence that the test was conducted under conditions established to detect specific behavioral changes, allowing for proper interpretation of results for novel compounds or genetic manipulations [12]. The convergence of data from multiple behavioral tests, coupled with correlating biochemical data, strengthens the reliability of mouse models or compounds being tested and enhances translational utility [12].

Comparative Analysis of Established Behavioral Assays

Cognitive Function Assays

The Attentional Set-Shifting Test (AST) represents a sophisticated behavioral assay developed to assess prefrontal cortical function in rats, specifically targeting cognitive flexibility [21]. This test models the ability to "unlearn" an established contingency to learn a new one by shifting attention from a previously salient stimulus dimension to a previously irrelevant one. The rodent AST adapts the clinical Wisconsin Card Sorting Test (WCST) used to assess strategy-switching deficits in patients with frontal lobe dysfunction [21]. In this paradigm, rats progress through a series of discrimination stages where they must dig in small flower pots to locate food rewards, with the relevant dimension (odor or digging medium) changing across stages. The primary dependent measure is the number of trials required to reach criterion at each stage, with specific impairment in extradimensional shifting indicating medial prefrontal cortex dysfunction, while reversal learning deficits specifically implicate orbitofrontal cortex function [21].

Experimental Protocol for AST:

- Rats are food-restricted to approximately 85% of free-feeding weight to ensure motivation for food rewards.

- Animals are habituated to the testing arena and trained to dig in flower pots for food rewards.

- Testing proceeds through seven stages: simple discrimination (SD), compound discrimination (CD), first reversal (R1), intradimensional shift (ID), second reversal (R2), extradimensional shift (ED), and final reversal (R3).

- At each stage, rats must reach a criterion of six consecutive correct responses before advancing.

- All stimuli (odors and digging media) are changed for the ID and ED stages to prevent stimulus-specific learning.

- The number of trials to criterion at each stage is recorded, with specific attention to ED stage performance as a measure of cognitive flexibility [21].

Social Behavior Assays

The Three-Chamber Social Interaction Test (SIT) represents the most widely utilized behavioral assay for assessing sociability in rodents [23]. This test evaluates an animal's preference for social versus non-social stimuli in a three-chambered apparatus with a wired cup containing a social partner in one chamber and an identical empty cup or object in the opposite chamber. Following habituation, the experimental animal freely explores the apparatus while interaction time with both cups is quantified. Despite its widespread use, SIT has yielded inconsistent results across different rodent models of ASD, potentially pointing to methodological limitations [23].

The Reciprocal Interaction Test (RCI) provides an alternative approach to assessing social behavior by placing two freely interacting animals in an open field arena and quantifying specific social behaviors including nose-to-nose, nose-to-anogenital, and side sniffing, while also recording non-social behaviors such as evading, escaping, or freezing in contact [23]. Recent head-to-head comparisons between SIT and RCI in a SHANK3 mouse model of autism spectrum disorder revealed significant discrepancies, with Shank3B(-/-) mice displaying normative sociability in SIT but exhibiting less than half the social interaction and almost three times more social disinterest compared to wild-type controls in RCI [23]. This disparity suggests that RCI may offer greater sensitivity for detecting social deficits in certain genetic models, highlighting the importance of assay selection for specific research questions.

Table 2: Comparison of Social Behavior Assays in Rodent Models

| Assay Characteristic | Three-Chamber Social Interaction Test (SIT) | Reciprocal Interaction Test (RCI) |

|---|---|---|

| Apparatus | Three-chambered box with wired cups | Open field arena |

| Social Stimulus | Contained social partner in cup | Freely interacting social partner |

| Primary Measures | Time in chambers; interaction time with cup | Direct social behaviors (sniffing); non-social behaviors |

| Advantages | Controlled social exposure; minimal aggression | Naturalistic interaction; broader behavioral repertoire |

| Limitations | Limited behavioral complexity; constrained interaction | Dominance effects; more complex scoring |

| Sensitivity in ASD Models | Variable across models; potentially less sensitive | Potentially higher sensitivity for specific deficits |

Anxiety and Depression-Related Assays

Innovative approaches to behavioral assessment include the development of hybrid assays that combine elements of multiple tests. The Light-Dark Forced Swim Test represents one such novel hybrid assay combining features of the light-dark test and forced swim test to simultaneously assess anxiety-like and depression-like behaviors [22]. This paradigm evaluates light-dark preference during swimming as a measure of anxiety-like behavior while recording immobility as an indicator of behavioral "despair." Validation studies demonstrate that the anxiety-like dark preference in female white outbred mice is sensitive to physiological anxiogenic stressors, while clinically active antidepressants reduce despair-like immobility, supporting its utility for simultaneous evaluation of anxiety- and depression-like behaviors [22].

The Elevated Plus Maze, Social Interaction Test, and Shock-Probe Defensive Burying Test represent additional well-validated assays for anxiety-like components of depression and anxiety disorders [21]. Each test operationalizes anxiety through different behavioral manifestations: open arm avoidance in the elevated plus maze, decreased social investigation in the social interaction test, and burying behavior in response to a shock-producing probe in the defensive burying test. The convergent use of multiple anxiety assays provides a more comprehensive assessment of anxiety-like behavior than any single test alone.

Emerging Applications and Innovative Approaches

Cross-Species Behavioral Paradigms

Behavioral assays have expanded beyond traditional rodent models to include innovative approaches in diverse species such as Drosophila melanogaster. The fruit fly offers powerful genetic tools and well-characterized neurocircuitry for investigating molecular mechanisms underlying complex behaviors [24]. Drosophila behavioral paradigms for autism research include social space analysis, aggression assays, courtship behavior analysis, grooming behavior, and habituation assays [24]. These approaches leverage the conservation of fundamental neurobiological processes across species while enabling high-throughput screening of genetic manipulations and pharmacological treatments.

The utility of Drosophila models is particularly evident in research on neurodevelopmental disorders, where hundreds of genes have been associated with autism spectrum disorders. Rather than a single Drosophila ASD model, researchers employ targeted genetic manipulations of individual ASD-related genes, followed by comprehensive behavioral characterization [24]. This approach has identified conserved molecular pathways underlying social behavior, repetitive behaviors, and habituation learning, providing insights into the neurobiological basis of ASD-related behavioral dimensions.

Advanced Translational Neuroscience Assays

Recent advances in translational neuroscience have incorporated human iPSC-derived neurons from both peripheral and central nervous systems, employing electrophysiological readouts including manual patch clamping and multi-electrode array (MEA) platforms [25]. These approaches enable recording of changes in single cell and neuronal network activity, determining effects of test compounds on targets and signaling pathways relevant to CNS diseases such as epilepsy, depression, anxiety, and neurodegeneration [25].

MEA recordings specifically allow interrogation of effects at both single neuron and network levels, monitoring physiological activity from native tissue or human stem cell-derived neurons bearing patient-derived disease mutations. This creates translational "disease-in-a-dish" phenotypic assays that bridge molecular mechanisms and cellular function [25]. Similarly, peripheral neuron phenotypic assays utilizing DRG (dorsal root ganglion) neurons enable target validation and engagement studies for pain and inflammation research, expanding the toolkit for translational neuroscience.

The Researcher's Toolkit: Essential Materials and Reagents

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Behavioral Neuroscience

| Reagent/Equipment | Primary Function | Application Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Automated Tracking Systems | Objective quantification of animal movement and behavior | EthoVision XT for social interaction tests, open field analysis |

| Multi-Electrode Array Platforms | Recording neuronal network activity | iPSC-derived neuron models for epilepsy, neurotransmitter effects |

| Biomarker Detection Assays | Quantification of neurological biomarkers in biological fluids | Ella platform for NF-L, NF-H in serum, plasma, CSF |

| Standard Anxiolytics/Antidepressants | Positive controls for assay validation | Diazepam for anxiety assays, fluoxetine for depression tests |

| Genetic Model Organisms | Investigation of gene function in behavior | SHANK3 models for ASD, Fmr1 models for Fragile X syndrome |

Behavioral assays remain indispensable tools in neuroscience research, providing critical bridges between biological mechanisms, neural circuits, and complex behavioral phenotypes. Their continued optimization and validation according to established methodological principles ensures the reliability and reproducibility necessary for translational success. As the field advances toward dimensional approaches that focus on specific symptom clusters and their underlying neurobiological mechanisms, behavioral assays will continue to evolve in sophistication and specificity. The integration of traditional behavioral paradigms with innovative approaches including cross-species models, human iPSC-based systems, and multi-electrode array technologies promises to enhance our understanding of neuropsychiatric disorders and accelerate the development of novel therapeutic strategies.

From Theory to Bench: A Guide to Key Assays and Model Organisms

Behavioral assays are indispensable tools in neuroscience and psychopharmacology research, providing critical windows into the cognitive and emotional states of animal models. The Open Field Test (OFT), Elevated Plus Maze (EPM), and Morris Water Maze (MWM) represent three foundational paradigms used extensively to evaluate anxiety-like behaviors, exploratory tendencies, and cognitive function in rodents. These tests leverage natural rodent behaviors—including thigmotaxis (wall-hugging), aversion to open spaces, and spatial navigation—to quantify complex behavioral outputs. Their validation against human disorders relies on careful experimental design, pharmacological sensitivity, and correlation with specific neural substrates. As the field moves toward increasingly sophisticated analysis techniques, understanding the comparative strengths, limitations, and optimal applications of these assays becomes paramount for researchers modeling human psychiatric and neurological conditions.

Comparative Analysis of Behavioral Assays

The table below provides a systematic comparison of the three behavioral assays, highlighting their primary applications, key behavioral measures, and neural correlates.

| Assay Name | Primary Behavioral Domain | Key Measured Parameters | Typical Testing Duration | Neural Substrates | Validity for Human Disorders |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Open Field Test (OFT) [26] | Anxiety, locomotor activity, exploratory behavior | - Distance traveled [27]- Time in center vs. periphery [26]- Rearing frequency [26]- Defecation/urination events [26] | 5-60 minutes [28] | Striatum [27] | Contested; best used in conjunction with other tests [26] |

| Elevated Plus Maze (EPM) [29] | Anxiety-like behavior | - % time in open arms- % entries into open arms- Total arm entries (activity measure) [29] | 5 minutes [30] | Not specified in search results | Good for GABAergic drugs (e.g., benzodiazepines); mixed results for novel anxiolytics [29] |

| Morris Water Maze (MWM) [31] | Spatial learning & memory, reference memory | - Escape latency- Path efficiency- Time in target quadrant (Probe trial)- Platform crossings (Probe trial) [31] | Multiple days (e.g., 5-6 days of training + probe trial) [31] | Hippocampus, Entorhinal cortex [19] | Strongly correlated with hippocampal function and NMDA receptor-dependent synaptic plasticity [31] |

Analysis of Key Metrics and Sensitivity

A critical consideration in selecting a behavioral assay is the sensitivity and reliability of its output measures. For the Morris Water Maze, a comparative analysis of different probe trial measures has revealed significant differences in their ability to detect group differences. Proximity (P), or the average distance from the target platform location, has been consistently shown to be a more sensitive measure than percent time in the target quadrant (Q), time in a target zone (Z), or the number of platform crossings (X), regardless of sample or effect size [32]. This superior performance is attributed to proximity capturing the spatial precision of the animal's search pattern throughout the entire trial, rather than relying on arbitrary boundaries or single-location crosses.

Recent technological advancements are further enhancing the sensitivity of these assays. The traditional analysis of the Open Field Test, which often relies on individual parameters like line crossings or center time, can fail to capture the complexity of animal movement [26]. Advanced computational approaches, such as modeling movement with fractional Brownian motion (fBm), characterize complex movement patterns through distinct asymptotic scaling regimes, uncovering significant insights obscured by simpler metrics [26]. Similarly, in the Morris Water Maze, novel vector-field analyses that measure Spatial Accuracy, Uncertainty, and Intensity of Search have proven more sensitive than classical measures, successfully detecting previously hidden differences in mouse models of genetic disorders [33]. The integration of machine learning, particularly deep neural networks, is also proving superior to classical methods for classifying animal behavior from sensor data, promising more nuanced and powerful analysis pipelines [34].

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Open Field Test (OFT) Protocol

The OFT is designed to assess general locomotor activity and anxiety-like behavior in rodents by leveraging their natural aversion to open, brightly lit areas and their tendency to stay close to walls (thigmotaxis) [26].

- Apparatus: A square or circular arena with walls to prevent escape. The size varies by species; for pigs, a high variability in dimensions has been noted across studies [28]. The field is conceptually divided into a peripheral zone near the walls and a more anxiogenic center zone [26].

- Procedure: The test subject is placed in the periphery of the arena (often near a wall) and allowed to explore freely for a set period, typically 5-60 minutes depending on the species and experimental design [28]. The test is conducted under indirect lighting to avoid creating bright hotspots [30]. Behavior is recorded for subsequent analysis.

- Data Collection & Analysis: Key parameters are tracked, ideally using automated video tracking software (e.g., EthoVision XT) to minimize bias [27]. Primary measures include:

- Locomotor Activity: Total distance traveled and line crossings [26] [27].

- Anxiety-like Behavior: Time spent in the center zone versus the periphery, and the number of entries into the center [26]. A decrease in center activity indicates higher anxiety.

- Exploratory Behavior: Rearing frequency (standing on hind legs), which can be unsupported or against the walls [26].

- Emotionality: The frequency of defecation and urination, though the interpretation of these as direct measures of anxiety is controversial [26].

Elevated Plus Maze (EPM) Protocol

The EPM exploits the conflict between a rodent's innate curiosity to explore a novel environment and its unconditioned fear of heights and open, brightly lit spaces [30] [29].

- Apparatus: A plus-shaped apparatus elevated from the floor with two open arms (without walls) and two enclosed arms (with high walls) that are arranged opposite each other. A central square connects all four arms [29].

- Procedure: The animal is placed in the central square of the maze, facing an open arm. The session typically lasts for 5 minutes [30]. Behavior is recorded both manually by a blinded observer and via video tracking software. If an animal falls, it is immediately placed back on the maze at the point where it fell, though its data may be excluded from analysis [30].

- Data Collection & Analysis: The primary measures focus on the animal's exploration of the more "dangerous" open arms, which is interpreted as reduced anxiety.

- Primary Anxiety Indices: Percentage of time spent in the open arms and the percentage of entries made into the open arms [29].

- General Activity: The total number of arm entries is used as a control measure for overall locomotor activity [29].

- Automated Tracking: Video software (e.g., AnyMaze) is used to track the distance traveled in each arm type and the number of entries [30].

Morris Water Maze (MWM) Protocol

The MWM is a gold standard for assessing spatial learning and reference memory in rodents by requiring them to learn the location of a hidden platform using distal spatial cues [31].

- Apparatus: A large circular pool (e.g., 120 cm in diameter) filled with opaque water maintained at a specific temperature (e.g., 28 ± 1°C). A hidden escape platform is submerged just below the water surface in a fixed location [31] [32].

- Procedure: The test involves multiple phases over several days.

- Spatial Acquisition (Training): Over several days (e.g., 5 days), animals undergo multiple trials per day (e.g., 4-6 trials). On each trial, they are started from different, semi-randomly varied points around the pool's perimeter and must learn to find the hidden platform using distal cues. If an animal fails to find the platform within the allotted time (e.g., 60 s), it is guided to the platform [31] [32].

- Probe Trial (Memory Test): Typically conducted 24 hours after the last acquisition day, the platform is removed from the pool, and the animal is allowed to swim for a fixed time (e.g., 60 s). This tests the strength and precision of the spatial memory for the former platform location [31] [32].

- Reversal Learning (Cognitive Flexibility): Often, the platform is moved to the opposite quadrant, and training continues for additional days. This assesses the animal's ability to extinguish the old memory and learn a new location [31].

- Data Collection & Analysis: Performance is tracked using automated video systems.

- Acquisition Learning: Escape latency and path efficiency to find the hidden platform are measured across trials [31].

- Probe Trial Memory: Spatial bias is quantified using measures like:

- Proximity (P): The most sensitive measure, it is the average distance from the target location during the probe trial [32].

- Percent Time in Target Quadrant (Q): Time spent in the quadrant that previously contained the platform.

- Platform Crossings (X): Number of times the animal crosses the exact former platform location [31] [32].

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

The table below outlines key materials and tools required for the proper execution and analysis of these behavioral assays.

| Item Name | Function/Description | Specific Application Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Automated Video Tracking System (e.g., EthoVision XT, AnyMaze) | Automates the recording and analysis of animal movement, minimizing human bias and improving reproducibility [27]. | Tracks center of gravity, nose/tail points, and calculates parameters like distance traveled, time in zones, and arm entries in OFT, EPM, and MWM [30] [27]. |

| Open Field Arena | Provides a standardized, featureless environment to assess exploration and anxiety. | A square or circular arena with walls; size is scaled to the species (mice, rats, or pigs) [26] [28]. |

| Elevated Plus Maze | A plus-shaped apparatus with open and closed arms to create an approach-avoidance conflict. | Used to test anxiety-like behavior; typically elevated 50 cm from the floor [29]. |

| Morris Water Maze Pool | A large circular tank filled with opaque water for testing spatial navigation. | The pool is typically 120 cm in diameter for mice/rats, with a hidden platform [31] [32]. |

| Animal-borne Sensors (Bio-loggers) | Miniature sensors (accelerometers, gyroscopes) record kinematic and environmental data. | Used for computational analysis of behavior (e.g., using benchmarks like BEBE) in more naturalistic or long-term settings [34]. |

| Analysis Software (e.g., Pathfinder, custom software) | Specialized software for analyzing spatial navigation paths and strategies. | Used to analyze search strategies in the MWM and calculate novel metrics like vector fields [33]. |