Advanced Strategies for Long-Term Mature Neuronal Culture: A Comprehensive Guide for Biomedical Research

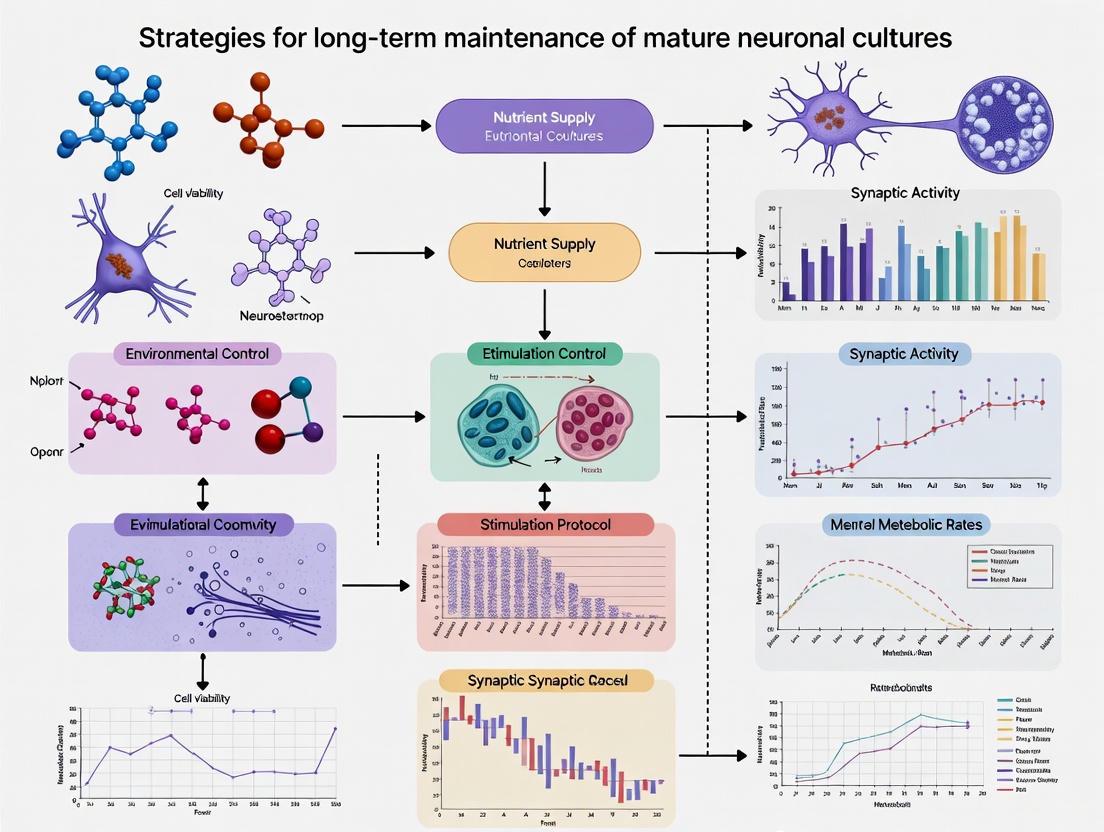

Maintaining the long-term health and functionality of mature neuronal cultures is a critical yet challenging endeavor in neuroscience research and drug development.

Advanced Strategies for Long-Term Mature Neuronal Culture: A Comprehensive Guide for Biomedical Research

Abstract

Maintaining the long-term health and functionality of mature neuronal cultures is a critical yet challenging endeavor in neuroscience research and drug development. This article provides a comprehensive guide based on the latest scientific advancements, addressing the unique vulnerabilities of post-mitotic neurons. We explore the foundational biology of neuronal genomic integrity and stability, detail optimized methodological protocols for culture setup and maintenance, present advanced troubleshooting and optimization techniques to mitigate common pitfalls like phototoxicity, and outline rigorous validation and comparative analysis frameworks. Designed for researchers and scientists, this resource synthesizes cutting-edge strategies to enhance the reliability and translational value of long-term neuronal culture models.

Understanding Neuronal Longevity: The Cellular and Molecular Basis for Stable Cultures

The Challenge of Genomic Instability in Post-Mitotic Neurons

Troubleshooting Guides

Troubleshooting Common Culture Health Issues

| Problem Symptom | Potential Cause | Recommended Solution | Preventive Measures |

|---|---|---|---|

| Neurons not adhering or clumping [1] [2] | Degraded or uneven coating substrate; plates plated at too high a density [1] [2]. | Switch from Poly-L-lysine (PLL) to the more protease-resistant Poly-D-lysine (PDL); ensure entire well surface is coated [2] [3]. | Thoroughly wash all excess substrate before plating to remove residual toxic fragments [3]. |

| Excessive glial cell contamination [2] | Proliferation of non-neuronal cells from primary tissue; use of serum-containing media [2] [3]. | Use serum-free media (e.g., Neurobasal); for full suppression, add CultureOne Supplement at day 0 [1] [2]. | Use embryonic tissue (E17-19 for rat) which has a lower density of glial precursors [2] [3]. |

| Poor cell health post-dissection [2] | Damage during dissection or dissociation; use of trypsin causing RNA degradation [2]. | Use papain as a gentler alternative to trypsin; allow neurons to rest after dissociation [2]. | Use embryonic neurons to minimize process shearing; perform gentle mechanical trituration and avoid bubbles [2]. |

| High levels of neuronal death [3] | Environmental stress after plating; improper media or supplements. | Minimize disturbances to culture (temp changes, agitation); let cultures adapt for several days post-plating [3]. | Use complete media systems designed for neurons; perform half-medium changes every 2-3 days [1] [2]. |

| Accumulation of DNA double-strand breaks (DSBs) [4] [5] | High metabolic activity and neuronal stimulation; defective DNA repair. | Research application: Investigate the NPAS4-NuA4 DNA repair pathway [5]. | Ensure optimal health to support endogenous repair mechanisms; avoid known DNA-damaging agents [6]. |

Troubleshooting Genomic Instability

| Problem Symptom | Potential Cause | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Increased γH2AX foci (DSB marker) [4] | Persistent DSBs due to inefficient NHEJ repair; oxidative stress from high metabolic rate [4] [6]. | Validate key NHEJ components (e.g., DNA Ligase IV, Ku70/80); assess mitochondrial function and ROS levels [4] [7]. |

| Accumulation of single-strand breaks (SSBs) [4] | Defective base excision repair (BER)/single-strand break repair; persistent PARP1 activation [4]. | Investigate key BER proteins (XRCC1, PARP1); monitor NAD+ levels as a readout of PARP1 overactivation [4] [7]. |

| Age-dependent mutation accumulation [6] | Gradual decline of DNA repair efficacy; lifetime of endogenous and exogenous insults [4] [6]. | Use younger passage cultures; model aging via prolonged culture or pro-oxidant challenges. |

| Activity-induced genomic instability [6] [5] | DSBs formed during activity-dependent gene expression (e.g., IEG activation) are not efficiently repaired [6]. | Modulate neuronal activity levels; investigate the NPAS4-NuA4 complex, a neuron-specific repair pathway for activity-induced breaks [5]. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Culture Maintenance

Q: What is the recommended media system for long-term culture of primary hippocampal neurons? A: For long-term culture, we recommend using Neurobasal Plus Medium supplemented with B-27 Plus Supplement. This system is optimized for better lot-to-lot consistency and supports long-term health. For short-term cultures of pure hippocampal neurons, Neurobasal-A Medium with B-27 Supplement can be used [1].

Q: How should I feed my neuronal cultures and how long can they be maintained? A: Perform half-medium exchanges with fresh, pre-warmed complete media every 2-3 days post-plating, taking care not to expose neurons completely to air [1]. With optimized systems, primary rat cortical neurons can be maintained for up to 8 weeks, and rat hippocampal neurons for up to 4 weeks [1].

Q: How can I control glial cell proliferation in my neuronal cultures? A: Using serum-free media like Neurobasal is essential. For complete suppression of both astrocytes and oligodendrocytes without neurotoxic effects, add CultureOne Supplement at day 0 of plating. Delaying its addition results in increased astrocyte levels [1].

Genomic Integrity

Q: Why are neurons particularly vulnerable to genomic instability? A: Neurons face unique challenges: they are post-mitotic, relying on error-prone repair pathways like NHEJ instead of high-fidelity homologous recombination [4] [7]; they have a high metabolic rate, generating reactive oxygen species (ROS) that damage DNA [6]; and their normal function, such as activity-dependent gene transcription, can intentionally induce DNA breaks [6] [5].

Q: What are the key DNA repair pathways active in mature neurons? A: The primary pathways are:

- Non-Homologous End Joining (NHEJ): The main pathway for repairing DNA double-strand breaks, involving proteins like Ku70/80, DNA-PKcs, and DNA Ligase IV [4] [7].

- Base Excision Repair (BER)/Single-Strand Break Repair (SSBR): Critical for repairing common oxidative lesions and single-strand breaks, involving XRCC1 and PARP1 [4] [7].

- Novel Neuron-Specific Mechanisms: The NPAS4-NuA4 complex is a recently identified pathway recruited to sites of activity-induced DNA damage to facilitate repair [5].

Q: How does neuronal activity lead to DNA damage, and how is it repaired? A: Neuronal stimulation, such as during novel environment exploration, can cause double-strand breaks, particularly near activity-induced promoters [6]. This is part of normal gene regulation. A neuron-specific complex, involving the transcription factor NPAS4 and the chromatin remodeler NuA4 (which includes TIP60), is recruited to these sites to orchestrate repair, linking neuronal activity directly to the DNA damage response machinery [5].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents & Materials

Research Reagent Solutions

| Item | Function/Application in Neuronal Research |

|---|---|

| Neurobasal Plus Medium | A serum-free basal medium optimized for neuronal culture, supporting long-term health and reduced glial growth [1]. |

| B-27 Plus Supplement | A defined, serum-free supplement designed to work synergistically with Neurobasal Plus Medium to promote neuronal survival and maturation [1]. |

| Poly-D-Lysine (PDL) | A positively charged polymer used to coat culture surfaces, facilitating neuronal adhesion. More resistant to proteolytic degradation than Poly-L-Lysine [1] [2]. |

| CultureOne Supplement | Used to fully suppress the proliferation of astrocytes and oligodendrocytes in mixed cultures without detrimental effects on neurons [1]. |

| Cytosine Arabinoside (AraC) | An antimitotic agent used to inhibit glial cell proliferation. Use with caution due to potential off-target neurotoxic effects at high concentrations [2]. |

| Papain | A gentle proteolytic enzyme used as an alternative to trypsin for tissue dissociation, minimizing damage to sensitive neurons [2]. |

Key Experimental Protocols & Visualizations

DNA Damage Response in Post-Mitotic Neurons

This diagram outlines the core signaling pathways neurons use to detect and respond to DNA damage, highlighting their reliance on the error-prone NHEJ pathway.

Activity-Dependent DNA Repair Workflow

This flowchart illustrates the experimental process for investigating the novel NPAS4-NuA4 repair pathway that responds to neuronal activity-induced DNA damage.

Quantitative Data for Neuronal Culture

| Experiment Type | Recommended Plating Density | Culture Duration | Key Health Indicators |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cortical Neurons (Biochemistry) [2] | 120,000 cells/cm² | Up to 8 weeks [1] | Adherence within 1 hour; axon outgrowth within 2 days [2]. |

| Cortical Neurons (Histology) [2] | 25,000 - 60,000 cells/cm² | Up to 8 weeks [1] | Dendritic outgrowth by day 4; mature network by 1 week [2]. |

| Hippocampal Neurons (Biochemistry) [2] | 60,000 cells/cm² | Up to 4 weeks [1] | Adherence and minor process extension within first two days [2]. |

| Hippocampal Neurons (Histology) [2] | 25,000 - 60,000 cells/cm² | Up to 4 weeks [1] | Formation of a mature neuronal network after one week [2]. |

Maintaining the long-term health and functionality of mature neuronal cultures is a complex challenge, central to advancing neuroscience research and drug development. A primary threat to culture viability is the accumulation of cellular damage from Reactive Oxygen Species (ROS), which act as a critical link between metabolic activity and detrimental effects on cellular components [8] [9]. ROS are generated from both endogenous sources, such as mitochondrial metabolism, and exogenous stressors, including environmental toxins [10]. At low concentrations, ROS play important physiological roles in cellular signaling; however, when their levels exceed the cellular antioxidant capacity, they induce oxidative stress, leading to macromolecular damage [9] [10]. This oxidative stress is particularly detrimental to post-mitotic neurons, resulting in lipid peroxidation, protein oxidation, and most critically, DNA damage [8] [9]. This guide provides troubleshooting protocols and FAQs to help researchers identify, mitigate, and resolve issues related to these stressors, thereby supporting the long-term maintenance of mature neuronal cultures.

FAQs & Troubleshooting Guides

Frequently Asked Questions

Q1: What are the primary internal (endogenous) sources of ROS in my mature neuronal cultures? The main endogenous source of ROS is the mitochondrial electron transport chain (ETC). During aerobic metabolism, a small percentage (0.1-2%) of electrons leak from complexes I and III, primarily reducing oxygen to the superoxide anion (•O2−), the precursor to most ROS [8] [9] [11]. Other enzymatic sources include NADPH oxidases (NOXs) and cytochrome P450 enzymes [8] [10].

Q2: How does oxidative stress lead to DNA damage in neurons? Oxidative stress causes DNA damage through the reaction of ROS, particularly the hydroxyl radical (•OH), with DNA components. This can result in strand breaks and oxidative damage to the pyrimidine and purine bases [8] [12]. A common and highly mutagenic lesion is 8-oxo-7,8-dihydroguanine (8-oxoG), which can mispair with adenine during replication, leading to permanent mutations [12]. This type of damage is a proposed mechanism behind neuronal genomic instability associated with aging and neurodegenerative disorders [12] [9].

Q3: My neuronal cultures show increased cell death over time. How can I determine if oxidative stress is a contributing factor? You can assess the level of oxidative stress using fluorescent probes. Follow the protocol in Section 3.1 to measure intracellular ROS with dyes like H2DCFDA or MitoSOX Red (for mitochondrial superoxide). A significant increase in fluorescence in your dying cultures compared to healthy controls strongly suggests oxidative stress involvement. Subsequent assays for oxidative DNA damage (Section 3.2) or lipid peroxidation can provide corroborating evidence.

Q4: What is the relationship between cellular metabolism and the DNA Damage Response (DDR)? The relationship is bidirectional. Metabolic pathways supply crucial substrates for DNA repair. For example, the pentose phosphate pathway (PPP) generates NADPH, which is essential for maintaining antioxidant systems and providing ribose for nucleotide synthesis [11] [13]. Conversely, DNA damage can reprogram cellular metabolism. The DDR kinase ATM can activate the PPP to fuel NADPH and nucleotide production for repair, while p53 can inhibit glycolysis to redirect glucose into the PPP [13].

Troubleshooting Common Problems

Problem: High Basal ROS Levels in Control Cultures

- Potential Causes:

- High metabolic activity: Neurons with overactive mitochondrial respiration.

- Sub-optimal culture conditions: Inadequate antioxidant supplementation in media, high oxygen tension (>21% O2).

- Microbial contamination: Low-grade, undetected contamination provoking an inflammatory response.

- Solutions:

- Optimize media: Supplement culture media with antioxidants such as N-acetylcysteine (NAC), glutathione, or catalase [9] [10].

- Modify atmosphere: Consider culturing under physiological oxygen tension (e.g., 3-5% O2) if equipment permits.

- Check for contamination: Perform thorough tests for mycoplasma and bacterial contamination.

Problem: High Background in DNA Damage Assays (e.g., Comet Assay)

- Potential Causes:

- Sample processing stress: Excessive light, heat, or mechanical shear during cell harvesting and processing can artificially induce DNA strand breaks.

- Inadequate lysis: Incomplete lysis of cells or presence of RNA can confound analysis.

- Apoptotic cells: A sub-population of dying, apoptotic cells with fragmented DNA.

- Solutions:

- Gentle handling: Process cells gently at 4°C, use minimal pipetting, and work under dim light.

- Optimize protocol: Ensure lysis buffer is fresh and contains recommended proteinase/RNase steps.

- Filter results: Use software gates to exclude obvious apoptotic cells (comets with very small heads and large tails) from the analysis of primary DNA damage.

Essential Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Measuring Intracellular ROS in Neuronal Cultures

This protocol uses the cell-permeant dye H2DCFDA, which is oxidized by broad-spectrum ROS to a fluorescent product, and MitoSOX Red, a mitochondrial superoxide indicator [14].

Workflow: Measurement of Intracellular ROS

Materials:

- H2DCFDA (e.g., Thermo Fisher Scientific D399) or MitoSOX Red (e.g., Thermo Fisher Scientific M36008)

- Pre-warmed Dulbecco's Phosphate Buffered Saline (DPBS), without Ca2+ and Mg2+

- Fluorescence-compatible culture medium (e.g., Phenol Red-free Neurobasal medium)

- Fluorescence plate reader or fluorescence microscope

Step-by-Step Method:

- Culture and Treat: Plate primary neurons or mature neuronal cell lines and allow them to reach the desired maturity. Apply your experimental treatments (e.g., pro-oxidant compounds, metabolic inhibitors).

- Dye Loading: Prepare a working solution of H2DCFDA (typically 1-10 µM) or MitoSOX Red (2.5-5 µM) in pre-warmed DPBS or serum-free medium.

- Incubation: Remove the culture medium from the cells and replace it with the dye-containing solution. Incubate for 30-45 minutes at 37°C in the dark.

- Washing: Carefully remove the dye solution and gently wash the cells 2-3 times with pre-warmed DPBS to remove excess probe.

- Analysis: Replace the DPBS with fluorescence-compatible medium. Immediately measure fluorescence using a plate reader (H2DCFDA: Ex/Em ~492-495/517-527 nm; MitoSOX Red: Ex/Em ~510/580 nm) or image using a fluorescence microscope.

- Normalization: Normalize fluorescence readings to total protein content or cell number for quantitative comparisons.

Protocol: Assessing Oxidative DNA Damage via Alkaline Comet Assay

The alkaline Comet Assay (Single Cell Gel Electrophoresis) is a sensitive technique for detecting single- and double-strand DNA breaks, which are hallmarks of oxidative DNA damage [12].

Workflow: Alkaline Comet Assay

Materials:

- Comet Assay Kit (e.g., Trevigen #4250-050-K) or individual components.

- Low-melting-point agarose

- Lysis buffer (e.g., 2.5 M NaCl, 100 mM EDTA, 10 mM Tris, 1% Triton X-100, pH 10)

- Alkaline electrophoresis buffer (300 mM NaOH, 1 mM EDTA, pH >13)

- Neutralization buffer (0.4 M Tris, pH 7.5)

- Fluorescent DNA stain (e.g., SYBR Gold, DAPI)

- Fluorescence microscope with analysis software (e.g., OpenComet)

Step-by-Step Method:

- Harvest and Embed: Gently harvest neuronal cells to avoid mechanical DNA damage. Mix approximately 10,000 cells with molten low-melting-point agarose (e.g., at 37°C) and immediately pipette onto a comet slide. Place a coverslip on top and allow it to solidify at 4°C in the dark for at least 10 minutes.

- Lysis: Carefully remove the coverslip and immerse the slide in freshly prepared, cold lysis buffer for a minimum of 1 hour (or overnight) at 4°C in the dark. This step removes cellular proteins and membranes, leaving the DNA as "nucleoids."

- Alkaline Unwinding: Remove the slide from the lysis buffer and place it in a horizontal electrophoresis tank filled with fresh, cold alkaline electrophoresis buffer for 20-60 minutes to allow DNA to unwind and express alkali-labile sites.

- Electrophoresis: Perform electrophoresis under alkaline conditions (e.g., 1 V/cm, 30 minutes). The exact time and voltage must be optimized for your system.

- Neutralization and Staining: Gently neutralize the slides by washing 2-3 times with neutralization buffer for 5 minutes each. Stain with a fluorescent DNA-binding dye according to the manufacturer's instructions.

- Analysis: Visualize comets using a fluorescence microscope. Analyze at least 50-100 randomly selected comets per sample using software. The key metric is % tail DNA, which correlates with the level of DNA damage.

Data Presentation: Quantitative ROS and DNA Damage Metrics

| ROS Species | Primary Source in Neurons | Half-Life | Key Detection Assays |

|---|---|---|---|

| Superoxide (•O₂⁻) | Mitochondrial ETC (Complex I/III), NOX enzymes [8] [11] | ~1 µs | MitoSOX Red, Cytochrome c reduction, DHE |

| Hydrogen Peroxide (H₂O₂) | Spontaneous or SOD-catalyzed dismutation of •O₂⁻ [8] [9] | ~1 ms | H2DCFDA, Amplex Red, HyPer probes |

| Hydroxyl Radical (•OH) | Fenton reaction (H₂O₂ + Fe²⁺/Cu⁺) [8] | ~1 ns | Aromatic hydroxylation (e.g., Salicylate trap), ESR |

| Singlet Oxygen (¹O₂) | Photosensitization reactions [8] | ~1 µs | SOSG, near-infrared chemiluminescence |

| DNA Lesion | Description | Resulting Mutation | Primary Repair Pathway |

|---|---|---|---|

| 8-oxoG | Oxidized guanine base that mispairs with adenine [12] | G:C to T:A transversion [12] | Base Excision Repair (BER) |

| Strand Breaks | Single- or double-strand breaks in the sugar-phosphate backbone [8] | Genomic instability, deletions | BER (SSB), HR/NHEJ (DSB) [13] |

| Base Deamination | Hydrolytic loss of an amine group from a base (e.g., Cytosine to Uracil) | C:G to T:A transition | Base Excision Repair (BER) |

| Abasic (AP) Site | Loss of a nitrogenous base, leaving a sugar moiety | Non-instructive, can block replication | Base Excision Repair (BER) [12] |

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Studying ROS and DNA Damage

| Reagent / Kit Name | Function / Target | Example Supplier(s) |

|---|---|---|

| H2DCFDA (DCFH-DA) | General oxidative stress sensor; measures broad-spectrum ROS. | Thermo Fisher, Abcam, Sigma-Aldrich |

| MitoSOX Red | Selective fluorescent probe for mitochondrial superoxide. | Thermo Fisher |

| CellROX Reagents | Fluorogenic probes for measuring oxidative stress in live cells. | Thermo Fisher |

| Comet Assay Kit | Complete kit for detecting DNA strand breaks at the single-cell level. | Trevigen, R&D Systems |

| Antibody: 8-oxo-dG | Antibody for detecting oxidized guanine in DNA via ELISA or ICC. | Abcam, Sigma-Aldrich, JaICA |

| N-Acetylcysteine (NAC) | Antioxidant precursor to glutathione; used to reduce oxidative stress. | Sigma-Aldrich, Tocris |

| MitoTEMPO | Mitochondria-targeted superoxide scavenger. | Sigma-Aldrich |

| PARP Inhibitor (e.g., Olaparib) | Tool compound to inhibit BER pathway and study its role. | Selleck Chem, Tocris |

Core Signaling Pathways

The interplay between metabolic activity, ROS generation, and the DNA damage response forms a critical signaling network that determines neuronal survival. The following diagram integrates key components from the provided research into a unified pathway relevant to mature neuronal cultures.

Pathway: Metabolic-ROS-DNA Damage Axis in Neurons

For researchers maintaining mature neuronal cultures, the long-term health of these non-dividing cells is paramount. Two crucial intracellular systems—DNA repair pathways and autophagy—work in concert to safeguard neuronal integrity and function. In postmitotic neurons, accumulated DNA damage and defective proteostasis are primary drivers of age-related decline and are implicated in numerous neurodegenerative diseases. Understanding the crosstalk between these systems provides a strategic framework for troubleshooting health and viability issues in long-term neuronal cultures. This technical support center outlines common challenges and provides targeted methodologies to diagnose and support these essential cellular defense mechanisms in your research models.

? Frequently Asked Questions for Mature Neuronal Cultures

Q1: Our mature neuronal cultures show increased markers of oxidative stress and decreased viability after 4 weeks. Could a breakdown in DNA repair be involved?

Yes. Neurons are particularly susceptible to oxidative DNA damage due to high metabolic activity. The Base Excision Repair (BER) pathway is the primary mechanism for repairing such lesions, like 8-oxoguanine [15]. Its failure can lead to accumulated DNA damage, triggering cell death. Implement the COMET assay protocol below to quantify DNA strand breaks and check for reduced expression of key BER proteins (e.g., OGG1).

Q2: We observe an accumulation of protein aggregates in our long-term cultures. How can we determine if autophagy is impaired?

The accumulation of protein aggregates, such as those containing p62/SQSTM1, is a classic indicator of impaired autophagic flux [16] [17]. Autophagy is the primary system for degrading aggregated proteins and damaged organelles. You can troubleshoot by:

- Western Blotting: Monitor levels of LC3-II and p62. A buildup of p62 alongside low LC3-II suggests blocked autophagic degradation.

- Immunostaining: Visualize aggregate formation using p62 antibodies.

- Use the flux assay detailed in the protocols section with Bafilomycin A1 to determine if the block is in initiation or degradation.

Q3: Does stabilizing G-quadruplex (G4) DNA structures affect neuronal health?

Yes. Recent studies show that stabilizing G4-DNA in neurons with ligands like Pyridostatin (PDS) can strongly downregulate the expression of Atg7, a critical gene for autophagy initiation [18]. This inhibition of autophagy can lead to neuronal dysfunction, accumulation of lipofuscin (a hallmark of aged brains), and memory deficits in model systems. This pathway represents a novel mechanism of autophagy regulation specific to neurons.

Q4: How are DNA damage response and selective autophagy of organelles linked?

DNA damage, especially from agents like ionizing radiation or chemotherapeutic drugs, can also damage subcellular organelles. In response, selective autophagy pathways are activated to remove these compromised components [19]:

- Mitophagy: Removes damaged mitochondria via the PINK1/Parkin pathway, preventing ROS accumulation.

- ER-phagy: Removes stressed fragments of the endoplasmic reticulum.

- Ribophagy: Targets damaged ribosomes. The clearance of these organelles via autophagy is crucial for resolving DNA damage and determining cell fate.

! Troubleshooting Common Experimental Challenges

Table 1: Common Problems and Solutions in DNA Repair and Autophagy Studies

| Observed Problem | Potential Cause | Recommended Solution | Key Assays for Verification |

|---|---|---|---|

| High basal apoptosis in control cultures | Accumulation of unrepaired DNA double-strand breaks (DSBs) | Optimize culture conditions to minimize oxidative stress; validate siRNA/shRNA specificity to avoid off-target DNA damage. | γH2AX immunofluorescence; COMET Assay [20] |

| Failed autophagic flux measurement | Inappropriate lysosome inhibitor concentration or timing | Titrate Bafilomycin A1 (e.g., 50-100 nM) or Chloroquine (e.g., 20-50 μM) and treat for a shorter duration (4-6 hours). | Western Blot for LC3-II and p62 [17] |

| Loss of neuronal viability after G4-DNA ligand treatment | Downregulation of ATG7 and inhibition of autophagy | Reduce ligand concentration (e.g., test low nM range of Pyridostatin); co-express G4-DNA unwinding helicases like Pif1 [18]. | qRT-PCR for Atg7 mRNA; Western Blot for ATG7 protein |

| Increased protein aggregation despite normal autophagy initiation | Impaired autophagosome-lysosome fusion | Check lysosomal health and acidity (LysoTracker); monitor key fusion proteins (e.g., LAMP-2, STX17) [17]. | Immunofluorescence (LC3 & LAMP-2 colocalization); Western Blot for LAMP-2 |

| Insufficient DNA damage response in neurons | Defects in the ATM/ATR signaling cascade | Verify activation of upstream damage sensors (e.g., MRN complex for ATM); use positive control (e.g., low-dose Etoposide). | Western Blot for p-ATM, p-CHK2, p-p53 [15] |

Table 2: Quantitative Markers of DNA Damage and Autophagic Activity

| Parameter | Baseline / Healthy Indicator | Stressed / Dysfunctional Indicator | Measurement Technique |

|---|---|---|---|

| DNA Double-Strand Breaks | <5 γH2AX foci/nucleus | >20 γH2AX foci/nucleus [20] | Immunofluorescence |

| Autophagic Flux (LC3-II turnover) | >2-fold increase in LC3-II with inhibitor | <1.5-fold increase in LC3-II with inhibitor [17] | Western Blot with Bafilomycin A1 |

| Oxidative DNA Damage (8-oxoG levels) | Low immunostaining intensity | High immunostaining intensity [15] | Immunofluorescence / ELISA |

| ATG7 Protein Level | Normal band intensity at ~78 kDa | >50% reduction in band intensity [18] | Western Blot |

| p62/SQSTM1 Level | Low, consistent band intensity | Strongly accumulated protein levels [16] | Western Blot / Immunostaining |

▽ Core Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: COMET Assay (Single-Cell Gel Electrophoresis) for Quantifying DNA Strand Breaks in Neurons

This protocol measures DNA single-strand and double-strand breaks at the single-cell level.

Materials:

- Low-Melting Point Agarose

- Normal Melting Point Agarose

- Lysing Solution (2.5 M NaCl, 100 mM EDTA, 10 mM Tris, 1% Triton X-100, pH 10)

- Neutral Electrophoresis Buffer (for DSBs, if needed)

- Fluorescent DNA Stain (e.g., SYBR Gold, Propidium Iodide)

Method:

- Embed Cells: Mix ~20,000 neurons with 1% low-melting point agarose and solidify on a comet slide.

- Lysis: Immerse slides in cold, freshly prepared lysing solution for at least 1 hour at 4°C.

- Electrophoresis: After lysis, place slides in an electrophoresis tank containing alkaline buffer (for SSBs and DSBs) or neutral buffer (primarily for DSBs). Run at ~1 V/cm for 20-30 minutes.

- Neutralization & Staining: Neutralize slides with Tris buffer (pH 7.5) and stain with a fluorescent DNA dye.

- Analysis: Score 50-100 randomly selected cells per sample using a fluorescence microscope and comet analysis software. The Tail Moment (percentage of DNA in the tail × tail length) is a key metric.

Protocol 2: Assessing Autophagic Flux Using LC3-II Turnover

This is a gold-standard biochemical method to determine if autophagy is being induced or blocked.

Materials:

- Lysosomal Inhibitors: Bafilomycin A1 (stock in DMSO) or Chloroquine (stock in water)

- Antibodies: Anti-LC3B antibody, Anti-p62/SQSTM1 antibody, Appropriate HRP-conjugated secondary antibody

- Lysis Buffer: RIPA buffer supplemented with protease and phosphatase inhibitors

Method:

- Treat Cells: Split your neuronal cultures into at least two groups. Treat one group with a lysosomal inhibitor (e.g., 100 nM Bafilomycin A1) for 4-6 hours. The other group serves as a vehicle control.

- Lyse and Quantify: Harvest cells in RIPA buffer and determine protein concentration.

- Western Blot: Load equal protein amounts (e.g., 20-30 μg) onto an SDS-PAGE gel. Transfer to a membrane and probe with anti-LC3B and anti-p62 antibodies.

- Interpretation:

- Induced Autophagy: LC3-II levels increase in the inhibitor-treated group compared to the control.

- Blocked Autophagy: LC3-II levels are already high in the control and do not increase (or increase less) with the inhibitor. p62 will typically accumulate.

Protocol 3: Modulating and Monitoring the G4-DNA - Autophagy Pathway

This protocol is for investigating the novel link between genomic G4-structures and autophagy [18].

Materials:

- G4-DNA Stabilizing Ligand: Pyridostatin (PDS) or BRACO-19

- Expression Vector for Pif1 Helicase (positive control)

- qRT-PCR reagents for Atg7 mRNA

Method:

- Treat Neurons: Apply PDS (e.g., 1-10 μM) to mature neuronal cultures for 24-48 hours. Include a DMSO vehicle control.

- (Optional) Rescue: Co-transfect neurons with a Pif1 expression vector prior to PDS treatment.

- Assess Downstream Effects:

- Atg7 Transcription: Extract mRNA and perform qRT-PCR for Atg7 levels. TBP can be used as a loading control. Expect a significant downregulation with PDS.

- ATG7 Protein & Autophagy: Perform Western Blotting for ATG7 and LC3-II/p62 to confirm functional inhibition of autophagy.

- Phenotypic Rescue: Overexpression of Pif1 should restore Atg7 expression and autophagic function in PDS-treated neurons.

Signaling Pathways and Crosstalk

The p53-DRAM Pathway in Autophagy Regulation

The tumor suppressor p53 is a key node linking DNA damage and autophagy, but its role is complex and location-dependent [16].

G4-DNA Mediated Regulation of Autophagy in Neurons

G-quadruplex (G4) DNA structures in the Atg7 gene provide a neuron-specific regulatory mechanism for autophagy [18].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents for Investigating DNA Repair and Autophagy

| Reagent / Tool | Primary Function | Example Application | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bafilomycin A1 | V-ATPase inhibitor; blocks lysosomal acidification and autophagosome degradation. | Measuring autophagic flux in Western Blot (LC3-II turnover) or fluorescence microscopy. | Titrate concentration (50-100 nM) and treatment time (4-6h) to avoid excessive toxicity. [17] |

| Chloroquine | Lysosomotropic agent; raises lysosomal pH to inhibit autophagic degradation. | In vivo or long-term in vitro inhibition of autophagy. | Generally less potent than Bafilomycin A1 but more cost-effective for large-scale studies. [16] |

| Pyridostatin (PDS) | Small-molecule G-quadruplex (G4) DNA stabilizer. | Investigating the novel pathway of G4-DNA-mediated regulation of autophagy gene (Atg7) expression. | Can induce DNA damage at higher doses; use appropriate controls. Neuron-specific effects are prominent. [18] |

| Etoposide | Topoisomerase II inhibitor; induces DNA double-strand breaks. | Positive control for activating the ATM/CHK2 DNA damage response pathway. | Use low doses (e.g., 1-10 μM) for a defined period to induce damage without triggering immediate apoptosis. [20] |

| LC3B Antibody | Detects both cytosolic (LC3-I) and lipidated, autophagosome-associated (LC3-II) forms of LC3. | Key readout for autophagy induction (increased LC3-II) and flux (with inhibitors). | The ratio of LC3-II to LC3-I or the total amount of LC3-II (with inhibitor) should be assessed. [17] |

| p62/SQSTM1 Antibody | Detects the selective autophagy receptor/cargo protein p62. | Indicator of autophagic degradation activity. Accumulation suggests impaired autophagy. | Always monitor p62 alongside LC3 for a complete picture of autophagic flux. [16] [17] |

| γH2AX Antibody | Recognizes histone H2AX phosphorylated at Ser139, a marker of DNA double-strand breaks. | Quantifying DSBs via immunofluorescence (foci counting) or Western Blot. | The number of foci per nucleus is a sensitive measure of DSBs. Distinguish between physiological and pathological levels. [20] [15] |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: Why is it so challenging to model age-related neuronal changes in standard in vitro cultures?

Standard in vitro models, particularly those using neurons derived from induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs), face a fundamental issue of "juvenility." The process of reprogramming somatic cells into iPSCs effectively resets the cellular age, erasing many age-dependent changes. Consequently, the resulting neurons often reflect an embryonic or early postnatal state, lacking the mature phenotypic and functional characteristics of aged adult neurons. This makes it difficult to study late-onset neurodegenerative diseases in these models [21]. Key reset mechanisms during reprogramming include:

- Epigenetic Remodeling: The reprogramming process resets epigenetic marks, including DNA methylation and histone modifications, making the epigenetic clock of iPSCs similar to that of embryonic stem cells [21].

- Telomere Lengthening: Telomeres are elongated, reversing the telomere attrition associated with aging in somatic cells [21].

FAQ 2: What are the primary signs of a healthy, maturing neuronal culture?

A healthy primary neuronal culture should show a predictable progression of development [2]:

- Within 1 hour: Neurons should adhere to the coated surface.

- Within 2 days: Neurons extend minor processes and show initial signs of axon outgrowth.

- By 4 days: Dendritic outgrowth should be observable.

- By 1 week: Neurons start forming a mature, interconnected network.

- Beyond 3 weeks: Cultures should be maintainable, demonstrating long-term viability and the presence of spontaneous electrical activity, which is a key indicator of functional maturation [22].

FAQ 3: How can I prevent glial cells from overgrowing my neuronal cultures?

Glial overgrowth is a common challenge. Strategies to manage this include:

- Use of Mitotic Inhibitors: Adding cytosine β-D-arabinofuranoside (Ara-C) at low concentrations (e.g., 5 μM) can inhibit the proliferation of glial cells. However, caution is advised as Ara-C can have off-target neurotoxic effects and should be used only when necessary [2] [22].

- Optimized Media: Using serum-free media like Neurobasal, supplemented with B27, is designed to support neuronal health while limiting glial proliferation [2].

- Physical Separation: For specific experimental needs, neuronal enrichment can be achieved using magnetic-activated cell sorting (MACS) with negative selection antibodies against non-neuronal cells (astrocytes, oligodendrocytes, microglia, endothelial cells) [23].

FAQ 4: Can I culture neurons from adult, rather than embryonic, brain tissue?

Yes, recent methodological advances have made it possible to culture mature adult central nervous system (CNS) neurons. This requires significant modifications to traditional protocols, focusing on extremely gentle tissue dissociation and the inclusion of survival factors [23].

- Key Modifications: Using gentle enzymatic digestion (e.g., papain) and mechanical dissociation, avoiding harsh steps like red blood cell lysis with ammonium chloride, and adding brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF, e.g., 20 ng/mL) to the culture medium are critical for success [23].

- Outcome: These cultured adult neurons can develop polarity, maintain resting membrane potentials, and exhibit spontaneous and evoked electrical activity, retaining characteristics of their native brain regions [23].

Troubleshooting Common Problems

Problem 1: Failure to Recapitulate Aging Phenotypes in iPSC-Derived Neurons

Potential Cause: The inherent "rejuvenation" of cells during iPSC reprogramming results in a juvenile neuronal phenotype that lacks age-associated molecular hallmarks [21] [24].

Solutions:

- Induced Aging Strategies: Actively induce cellular senescence and maturation in culture. Common approaches include:

- Progerin Overexpression: Ectopic expression of progerin, a protein associated with premature aging [21].

- Chemical Stressors: Application of sub-lethal oxidative or toxic stress to accelerate aging-related pathways [21].

- Extended Culture: Maintaining cultures for prolonged periods (e.g., beyond 14 days in vitro) to allow for spontaneous maturation and network development, which is crucial for functional phenotypes [22].

- Alternative Model: Direct Conversion: Consider using directly converted neurons. This method transforms fibroblasts directly into neurons, bypassing the pluripotent stage, and has been reported to better preserve an aged molecular phenotype [21].

Problem 2: Poor Survival and Adhesion of Dissociated Primary Neurons

Potential Cause: Cell damage during the dissection or dissociation process, or an inadequate growth substrate [2].

Solutions:

- Optimize Dissection:

- Use embryonic tissue (e.g., E17-19 for rats) as it has a lower glial density and less defined arborization, reducing shearing damage [2].

- Consider using papain instead of trypsin for enzymatic dissociation, as trypsin can cause RNA degradation and higher cellular stress [2] [22].

- Perform mechanical trituration gently and avoid creating bubbles to prevent shearing by surface tension [2].

- Verify Coating Substrate:

- Ensure culture surfaces are properly coated with adhesion-promoting substrates like poly-D-lysine (PDL) or poly-L-lysine (PLL). PDL is more resistant to enzymatic degradation than PLL [2].

- If degradation persists, switch to a more robust substrate like dendritic polyglycerol amine (dPGA), which lacks peptide bonds and is highly resistant to protease activity [2].

- A recommended coating protocol is to use PLL (0.1 mg/mL) for 1 hour at room temperature, followed by natural mouse laminin (5 μg/mL) overnight at 4°C [22].

Problem 3: Lack of Functional Maturation and Network Activity

Potential Cause: Suboptimal culture conditions, including insufficient density, inadequate nutrients, or lack of trophic support, preventing the development of a functional network.

Solutions:

- Ensure Proper Seeding Density: Plate neurons at an appropriate density to encourage network formation. General guidelines for rat primary neurons are [2]:

- Cortical neurons: 120,000/cm² for biochemistry; 25,000 - 60,000/cm² for histology.

- Hippocampal neurons: 60,000/cm² for biochemistry; 25,000 - 60,000/cm² for histology.

- Optimize Culture Medium:

- Use serum-free medium like Neurobasal-A, supplemented with B27 and GlutaMAX [2] [22].

- Perform half-medium changes every 3-7 days to provide fresh nutrients and growth factors while maintaining conditioned factors secreted by the neurons [2] [22].

- Add survival factors such as BDNF (20 ng/mL) to support mature neurons [23].

Table 1: Key Molecular Hallmarks of Aging to Model and Assess In Vitro [21] [25]

| Hallmark Category | Specific Target/Process | Potential Experimental Readout |

|---|---|---|

| Genomic Instability | Nuclear DNA damage foci (DNA-SCARS), cytoplasmic DNA (mtDNA, ccDNA) | γH2AX staining, cGAS/STING pathway activation [25] |

| Epigenetic Alterations | DNA methylation patterns, histone modifications (e.g., H3K9me3, H3K27ac) | Epigenetic clock analysis, ChIP-seq [21] |

| Loss of Proteostasis | Protein aggregation, compromised autophagy | Immunostaining for protein aggregates (e.g., p-tau), LC3-I/II conversion assay [25] |

| Mitochondrial Dysfunction | Increased ROS, decreased mtDNA copy number, altered membrane potential | MitoSOX Red, qPCR for mtDNA, TMRE staining [25] |

| Cellular Senescence | Senescence-Associated β-Galactosidase (SA-β-Gal), p16INK4a, p21 | SA-β-Gal staining, Western blot for p16/p21 [24] |

| Altered Intercellular Communication | Senescence-Associated Secretory Phenotype (SASP) | Multiplex cytokine array (e.g., for IL-6, IL-8) [25] |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents & Protocols

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Materials for Advanced Neuronal Culture and Aging Studies

| Reagent / Kit | Function / Application | Example Use-Case |

|---|---|---|

| Adult Brain Dissociation Kit | Gentle enzymatic and mechanical dissociation of mature brain tissue. | Culturing neurons from adult mouse brain (up to PND 90) [23]. |

| MACS Neuro Media & Neuron Isolation Kit | Serum-free medium and kit for the magnetic enrichment of neurons via negative selection. | Isating a highly pure neuronal population from a mixed brain cell dissociate [23]. |

| Poly-D-Lysine (PDL) | A protease-resistant substrate for coating culture vessels to promote neuronal adhesion. | Providing a stable surface for long-term neuronal cultures; preferred over PLL if degradation is an issue [2]. |

| Hibernate-E Medium | A shipment medium designed to stabilize neuronal cell cultures at low temperatures. | Shipping live primary neuronal cultures between collaborating laboratories [22]. |

| Brain-Derived Neurotrophic Factor (BDNF) | A key trophic factor that supports the survival and maturation of cortical and other CNS neurons. | Essential supplement for the successful culture of adult CNS neurons [23]. |

| Cytosine β-D-arabinofuranoside (Ara-C) | A mitotic inhibitor used to suppress glial cell proliferation. | Controlling glial overgrowth in primary neuronal cultures post-seeding [22]. |

| B-27 Supplement | A defined serum-free supplement optimized for the survival and growth of central nervous system neurons. | Standard component of Neurobasal-based media for primary neuron culture [2] [22]. |

| Papain | A proteolytic enzyme used for gentle tissue dissociation, considered less damaging than trypsin. | Dissociating embryonic or postnatal brain tissue for primary culture [2] [22]. |

Detailed Protocol: Culturing Adult CNS Neurons

This protocol is adapted from methods that enable the culture of neurons from mature adult mice (up to 60-90 days post-natal) [23].

Workflow Overview:

Step-by-Step Methodology:

- Dissection: Grossly dissect the desired brain region (e.g., motor cortex, hippocampus) as a single 4-8 mm tissue block. Critical: Avoid further chopping or mincing of the tissue to minimize trauma [23].

- Dissociation:

- Immerse tissue blocks in Dulbecco's PBS (with glucose, calcium, magnesium).

- Transfer tissue to a solution containing papain and DNAse.

- Place the tube into a gentle mechanical dissociator (e.g., GentleMACS Octo Dissociator with heaters) and run the program at 37°C for 30 minutes [23].

- Cell Separation and Enrichment:

- Pass the resulting tissue suspension through a 70-μm cell strainer.

- Centrifuge and resuspend the cell pellet in a Percoll solution for density gradient centrifugation (3,000 x g, 10 min, 4°C). Collect cells from the bottom phase [23].

- Critical Modification: At this stage, omit the standard ammonium chloride-based red blood cell lysis step, as it is too harsh for adult neurons. Instead, add BDNF (20 ng/mL) to the cell solution as a survival factor [23].

- Enrich neurons using a negative selection MACS protocol. Incubate the cell mixture with a cocktail of biotinylated antibodies against non-neuronal cells (astrocytes, oligodendrocytes, microglia, endothelial cells), then pass through an LS magnetic column. Neurons will pass through while labeled non-neuronal cells are retained [23].

- Plating and Maintenance:

- Resuspend the eluted neurons in MACS Neuro Media supplemented with B27, GlutaMAX, and 20 ng/mL BDNF.

- Plate cells on PDL/laminin-coated surfaces at the desired density.

- Maintain cultures with half-medium changes every 3-4 days, ensuring BDNF and other supplements are replenished.

Detailed Protocol: Shipping Live Primary Neurons

This protocol allows for the shipment of viable primary neuronal cultures, enabling collaboration and centralization of culture preparation [22].

Workflow Overview:

Step-by-Step Methodology:

- Preparation: Culture primary neurons (e.g., from postnatal day 0-1 mouse hippocampi or cortices) following standard isolation protocols for 2 days in vitro (DIV) [22].

- Pre-shipment: Just prior to shipping, completely aspirate the culture medium and immediately replace it with ice-cold Hibernate-E medium, filling the wells completely. Hibernate-E is designed to stabilize cells at low temperatures [22].

- Packaging:

- Seal the culture plate with an adhesive seal and wrap the entire plate with Parafilm to prevent leakage.

- Place the plate in a Styrofoam shipping container with pre-cooled 4°C ice packs.

- Fill empty space with bubble wrap to prevent movement and ship via an overnight courier service.

- Recovery:

- Upon arrival, unpack the neurons and immediately place them in a 37°C, 5% CO₂ incubator for 2 days to recover.

- At 4 DIV, perform a half-medium change, replacing Hibernate-E with standard culture medium (e.g., Neurobasal-A/B-27) supplemented with 5 μM Ara-C to inhibit proliferating glial cells [22].

- Continue with standard maintenance, performing half-medium changes every 3 days. Cultures are typically ready for functional experiments like electrophysiology by 14 DIV [22].

Why Primary Cells? Advantages Over Immortalized Cell Lines for Physiological Relevance

Within the context of strategies for the long-term maintenance of mature neuronal cultures, the selection of an appropriate cellular model is a foundational decision. While immortalized cell lines have been integral to scientific advancement, increasing concerns regarding their physiological relevance have led many neuroscientists to adopt primary cells for more predictive in vitro modeling [26]. Primary cells, isolated directly from tissues and possessing a finite lifespan, offer superior genetic and phenotypic stability and retain key in vivo characteristics that are often lost in continuously passaged cell lines [26]. This technical support center outlines the core advantages of primary neuronal cultures and provides practical troubleshooting guidance to overcome common experimental challenges, thereby supporting robust and physiologically relevant research outcomes.

The fundamental distinction lies in the origin and handling of the cells. Primary neuronal cultures are obtained by direct isolation from nervous tissue, such as the cortex or hippocampus, and are not transformed for infinite proliferation [22] [27]. In contrast, immortalized cell lines (e.g., SH-SY5Y, PC12) are typically derived from neuronal tumors and have been genetically altered to divide indefinitely, often resulting in a shift of cellular resources toward proliferation at the expense of native functions [26] [28]. For researchers focusing on long-term cultures of mature neurons, this trade-off is critical; primary cultures maintain post-mitotic states and complex synaptic networking, which are essential for studying neuronal maturation, connectivity, and degenerative processes [22] [27].

Key Advantages of Primary Cells

The adoption of primary cells is driven by their ability to generate more meaningful and predictive data. The core benefits are summarized in the table below.

Table 1: Core Advantages of Primary Cells over Immortalized Cell Lines

| Advantage | Description | Impact on Research |

|---|---|---|

| Enhanced Physiological Relevance | Retain native morphology, gene expression patterns, and electrophysiological activity [22] [28]. | Data more accurately predicts in vivo outcomes, enhancing the translational value of basic research. |

| Genetic & Phenotypic Stability | Finite culture period prevents the genetic drift and proteomic changes common in long-term passaged cell lines [26]. | Ensures consistent experimental results and reliable interpretation across studies. |

| Representation of Donor Variability | Inherently reflect the biological diversity between donors (e.g., in HLA type or CMV status) [26]. | Allows researchers to account for population diversity, minimizing broad assumptions derived from homogeneous cell lines. |

| Reduced Contamination & Misidentification Risks | Lower risk of cross-contamination and identity changes that frequently plague immortalized lines like HeLa [26]. | Reduces the time, cost, and effort required for extensive cell line authentication. |

For neuronal studies specifically, primary cells are a more appropriate model because they are post-mitotic and capable of exhibiting spontaneous, physiological activity, forming functional synapses that are critical for neuropharmacology and toxicology research [22] [28]. Immortalized neuroblastoma cells, while practical, often exhibit immature neuronal features and may lack consistent expression of key ion channels and receptors, limiting their utility for studying complex neurological signaling [28].

Troubleshooting Common Challenges in Primary Neuronal Culture

Working with primary neurons requires careful technique to ensure high viability and functionality. Below are common issues and their evidence-based solutions.

Table 2: Troubleshooting Guide for Primary Neuronal Cultures

| Problem | Possible Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Low Cell Viability After Thawing | Improper thawing technique or osmotic shock. | Thaw cells quickly (<2 mins at 37°C). Use pre-warmed medium and add medium to cells drop-wise initially to minimize osmotic stress. Do not centrifuge extremely fragile neurons post-thaw [29]. |

| Poor Cell Attachment | Coating matrix dried out; insufficient coating; or incorrect seeding density. | Shorten the time between removing the coating solution and adding cells. Ensure plates are properly coated with PLL/Laminin. Verify the correct, lot-specific seeding density [29] [30]. |

| Holes in Monolayer / Dying Cells | Toxicity from test compounds; sub-optimal culture medium; or cells cultured for too long. | Review compound concentration. Use fresh, validated culture medium (e.g., Neurobasal-A with B-27 supplement). Do not culture plateable hepatocytes for more than five days; primary neuron limits vary [29]. |

| Excessive Glial Contamination | Lack of mitotic inhibitor in culture. | After neuronal attachment (e.g., 4 DIV), add a mitotic inhibitor like cytosine β-D-arabinfuranoside (Ara-C) to the culture medium to suppress glial cell proliferation [22]. |

| Low Transfection Efficiency | Primary cells are inherently more sensitive than cell lines. | Use specialized transfection reagents or viral transduction protocols designed for sensitive primary cells. Contact technical support for reagent recommendations [29]. |

Workflow for Establishing Primary Neuronal Cultures

The following diagram illustrates the key stages in the process of isolating and maintaining primary neuronal cultures, highlighting critical steps that influence cell health and experimental success.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: My primary neurons are not forming functional synapses. What could be wrong? A1: Ensure cultures are maintained for a sufficient duration (at least 14 Days In Vitro) to allow for maturation [22]. Also, verify that your culture medium is fresh and contains the correct supplements. The B-27 supplement is critical for neuronal health, but it loses efficacy if expired, improperly stored, or thawed/refrozen multiple times [29].

Q2: Can I passage my primary neurons? A2: No. Mature primary neurons are post-mitotic and cannot be proliferated or passaged like cell lines. Each culture is a finite resource, and experiments must be planned accordingly using the appropriate seeding density at the initial plating [27].

Q3: How can I share my primary neuronal cultures with a collaborator at a distant institution? A3: Yes, shipping live primary neuronal cultures is feasible. One documented method involves replacing the culture medium with ice-cold Hibernate-E medium at 2 DIV, completely filling the wells, sealing the plate multiple times with parafilm, and shipping overnight in a Styrofoam container with pre-cooled ice packs. Upon receipt, cultures are unpacked and returned to a 37°C incubator [22].

Q4: Why are there so many large, flat cells in my neuronal culture after a week? A4: This is likely glial cell (e.g., astrocyte) overgrowth. To mitigate this, treat cultures with a mitotic inhibitor like cytosine β-D-arabinfuranoside (Ara-C) around 4 DIV, which will inhibit the division of non-neuronal cells while leaving post-mitotic neurons unaffected [22].

Q5: Are there alternatives if I cannot source human primary neurons? A5: While human primary cells are the gold standard, researchers often use rodent-derived primary neurons [30]. Newer technologies like human induced pluripotent stem cell (iPSC)-derived neurons (e.g., ioCells) are also emerging as a reproducible, scalable, and human-relevant alternative that combines the physiological relevance of primary cells with the practicality of cell lines [28].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents for Primary Neuronal Culture

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Primary Neuronal Culture

| Reagent | Function | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Neurobasal Medium | A serum-free medium optimized for the long-term survival and maturation of primary neurons [22]. | Often used in combination with B-27 to prevent astrocyte overgrowth. |

| B-27 Supplement | Provides essential hormones, antioxidants, and proteins for neuronal health and function [22] [29]. | Check expiration date. Thawed supplement is stable for only 1-2 weeks at 4°C. Avoid repeated freeze-thaw cycles [29]. |

| Poly-L-Lysine (PLL) & Laminin | Substrate coating proteins that promote neuronal attachment and neurite outgrowth [22] [30]. | Coated plates should not be allowed to dry out before cell seeding, as this compromises attachment [29]. |

| Hibernate-E | A shipping medium designed to stabilize neuronal cultures at lower temperatures (e.g., 4°C) during transport [22]. | Enables sharing of live cultures between laboratories. |

| Cytosine β-D-arabinfuranoside (Ara-C) | A mitotic inhibitor that selectively kills dividing glial cells, thereby enriching the neuronal population [22]. | Typically added a few days after plating, once neurons have attached. |

| Papain & Dispase II | Enzymes used in combination for the gentle dissociation of neural tissue into a single-cell suspension during isolation [22] [30]. | Critical for achieving high cell viability and yield during the initial preparation. |

Decision Framework: Selecting Your Cellular Model

Choosing between primary cells, immortalized lines, and newer models depends on your research question, resources, and goals. The following diagram outlines a strategic decision-making pathway.

For research strategies centered on the long-term maintenance of mature neuronal cultures, primary cells offer an indispensable model that prioritizes physiological relevance and translational potential. While they present technical challenges such as finite lifespan and culture sensitivity, the protocols and troubleshooting guides outlined in this document provide a clear roadmap to success. By adhering to optimized isolation methods, careful handling, and appropriate maintenance protocols, researchers can reliably leverage primary neuronal cultures to generate robust, predictive data that advances our understanding of neural function and disease.

Building for Stability: Step-by-Step Protocols for Robust Long-Term Cultures

The success of long-term research on mature neuronal cultures is fundamentally determined by the initial steps of neuron isolation. Isolating primary neurons from brain tissue is a delicate process that requires precise technique and an understanding of the unique challenges posed by these post-mitotic cells. This guide addresses common pitfalls and provides evidence-based solutions to ensure researchers can consistently obtain high-viability, functionally mature neuronal cultures for their experimental needs.

Troubleshooting Guide: Common Challenges in Primary Neuron Isolation

Table 1: Troubleshooting Common Issues in Primary Neuron Isolation

| Problem | Potential Causes | Recommended Solutions |

|---|---|---|

| Low Cell Viability Post-Dissociation | Over-digestion with proteolytic enzymes like trypsin; excessive mechanical trituration; prolonged dissection time. | Use papain as a gentler enzyme alternative [2]; limit dissection time to 2-3 minutes per embryo [30]; perform gentle trituration while avoiding bubble formation [2]. |

| Poor Neuronal Adhesion | Inadequate or degraded coating substrate; suboptimal plating density; presence of toxic substances. | Use Poly-D-Lysine (PDL), which is more resistant to protease degradation than Poly-L-Lysine (PLL) [2]; ensure coating solution does not dry out [29]; verify correct cell counting and plate at recommended densities [2]. |

| Excessive Glial Contamination | Use of postnatal animals with higher glial content; serum-containing media promoting glial growth; absence of anti-mitotic agents. | Isolate neurons from embryonic stages (e.g., E17-E19 for rats) when possible [2]; use serum-free media like Neurobasal with B-27 supplement [30] [2]; if necessary, use low-concentration cytosine arabinoside (AraC) with caution due to potential neurotoxicity [2]. |

| Unhealthy Neuronal Morphology & Poor Network Formation | Suboptimal culture medium; outdated or improperly stored supplements; incorrect osmolarity/pH. | Prepare culture medium fresh with newly diluted supplements weekly [2]; ensure B-27 supplement is not expired, repeatedly thawed/frozen, or exposed to excessive heat [29]; perform half-medium changes every 3-7 days [2]. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is the optimal developmental stage for isolating primary neurons to maximize yield and minimize glial contamination? The ideal stage is embryonic. For rat cortical neurons, Embryonic Day 17-18 (E17-E18) is most commonly used [30] [2]. Embryonic tissue generally yields a higher density of neurons with less developed arbors that are less susceptible to shearing during dissection, and it contains a lower proportion of glial cells compared to postnatal tissue [2].

Q2: What are the key advantages of using primary neurons over immortalized neuronal cell lines? Primary neurons are post-mitotic and genetically stable, allowing them to closely mimic the in vivo environment and provide more physiologically relevant data [30] [31]. Immortalized cell lines often have disrupted normal physiological functioning due to genetic modification and may accumulate mutations over time, making them less suitable for many applications [31] [32].

Q3: My neurons are clumping and not adhering properly. What should I check in my substrate coating protocol? This is often a sign of substrate degradation or issues with the coating process [2]. First, ensure you are using a robust coating substrate like Poly-D-Lysine (PDL), which is more resistant to enzymatic breakdown than PLL [2]. Second, avoid letting the coated surface dry out completely, as this can destroy its attachment properties. Work with a few wells at a time during plating to minimize the interval between removing the coating solution and adding cells [29].

Q4: How can I effectively reduce glial overgrowth in my neuronal cultures without harming the neurons? The most effective strategy is a combination of approaches:

- Source: Use embryonic tissue, which has a lower initial glial population [2].

- Medium: Culture in serum-free Neurobasal medium supplemented with B-27, which is optimized for neuronal survival and suppresses glial proliferation [2].

- Anti-mitotics: If glial contamination persists, the use of low-concentration cytosine arabinoside (AraC) is an established method, but it should be used cautiously due to reported off-target neurotoxic effects [2].

Q5: What are the critical steps during the dissociation process to ensure high neuron viability? The dissociation phase is highly critical. To protect your neurons:

- Enzyme Choice: Consider using papain instead of trypsin, as trypsin can cause RNA degradation and is harsher on cells [2].

- Mechanical Trituration: Be gentle. Avoid creating bubbles during pipetting, as the surface tension can shear and damage cells [2].

- Post-Dissociation Rest: Allow the dissociated neurons a short rest period after dissociation and before plating. This can significantly improve their ability to adhere and extend processes [2].

Workflow and Method Selection

The following diagram summarizes the core workflow for the isolation and initial culture of primary neurons, integrating key decision points and best practices.

Diagram 1. Workflow for Primary Neuron Isolation and Culture. The path highlights recommended practices (red nodes) for optimal outcomes.

Q6: What methods are available for isolating specific neural cell types (e.g., neurons, astrocytes, microglia) from the same tissue sample? For studies requiring specific cell populations, advanced isolation techniques can be employed:

- Immunocapture using Magnetic Beads: This method uses antibodies against cell-specific surface markers (e.g., CD11b for microglia, ACSA-2 for astrocytes) conjugated to magnetic beads. Cells are separated by applying a magnetic field, allowing for sequential isolation of different cell types from a single suspension [31] [32].

- Percoll Gradient Centrifugation: This is a density-based separation technique that can isolate microglia and astrocytes without the need for expensive antibodies or enzymatic digestion, which can sometimes affect cell viability [31] [32].

Table 2: Comparison of Primary Neuron Isolation Methods from Different Nervous System Regions

| Neuron Source | Recommended Animal Age | Key Dissection Considerations | Typical Plating Density for Histology |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cortex | E17-E18 (Rat) [30] | Limit dissection time to 2-3 min/embryo; completely remove meninges to ensure purity [30]. | 25,000 - 60,000 cells/cm² [2] |

| Hippocampus | P1-P2 (Rat) [30] or P0-P2 (Mouse) [33] | Identify C-shaped structure in posterior 1/3 of hemisphere; careful removal is crucial [30]. | 25,000 - 60,000 cells/cm² [2] |

| Spinal Cord | E15 (Rat) [30] | Requires careful dissection of the embryonic spinal column. | Protocol-specific |

| Dorsal Root Ganglia (DRG) | 6-week-old young adult (Rat) [30] | DRG neurons are peripheral sensory neurons; culture medium requires NGF [30]. | Protocol-specific |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Primary Neuronal Culture

| Reagent/Material | Function/Purpose | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Poly-D-Lysine (PDL) | Coating substrate that provides a positively charged surface for neuron attachment. | More resistant to proteolytic degradation than Poly-L-Lysine (PLL), leading to more stable adhesion [2]. |

| Neurobasal Medium | Serum-free medium optimized for long-term survival of central nervous system neurons. | Suppresses glial cell proliferation; must be supplemented [2]. |

| B-27 Supplement | Serum-free supplement containing hormones, antioxidants, and other necessary nutrients. | Critical for neuron health. Use fresh aliquots; avoid repeated freeze-thaw cycles; check for expiration [2] [29]. |

| Papain | Proteolytic enzyme for tissue dissociation. | Gentler alternative to trypsin; can help improve RNA integrity and cell viability post-dissociation [2]. |

| Cytosine Arabinoside (AraC) | Anti-mitotic agent that inhibits DNA synthesis. | Used to control glial cell overgrowth. Use at low concentrations and only when necessary due to potential neurotoxic side effects [2]. |

The extracellular matrix (ECM) provides the essential structural and biochemical microenvironment for cells in vitro, directly influencing cell adhesion, proliferation, differentiation, and long-term survival. For researchers focusing on mature neuronal cultures, selecting the appropriate ECM coating is a critical determinant of experimental success. This guide provides a comparative analysis of common ECM coatings, with a specific focus on laminin, and offers practical troubleshooting advice to address common challenges in neuronal culture work.

ECM Coating Comparison: From Structural Support to Signaling

The table below summarizes the key characteristics, mechanisms, and optimal applications of four common ECM coatings, providing a basis for selection.

| ECM Coating | Key Characteristics & Composition | Primary Receptors | Impact on Neural Cells | Recommended Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Laminin | Trimeric glycoprotein (α, β, γ chains); major component of native basement membrane [34] [35]. | Integrins (e.g., α6β1), dystroglycan [36] | ↑ Proliferation, ↑ Differentiation, ↓ Apoptosis, enhances neurite outgrowth [37] [36]. | Primary neuronal cultures, neural stem cell expansion & differentiation, long-term mature culture maintenance. |

| Poly-D-Lysine (PDL) | Synthetic polymer; creates a positive, adhesive surface. | Non-specific charge interactions | Strong initial cell attachment; provides limited biological signaling. | Rapid attachment of neurons, often used as a preliminary coating before adding laminin. |

| Collagen I | Abundant fibrillar protein in connective tissue. | Integrins (e.g., α2β1) | Supports general adhesion; may promote a more fibroblastic phenotype [38]. | General cell culture, 3D culture models, co-cultures with fibroblasts. |

| Fibronectin | Glycoprotein involved in wound healing and cell adhesion. | Integrins (e.g., α5β1) | Supports cell adhesion and migration. | Neural crest cell studies, migration assays. |

Experimental Protocols: Implementing Laminin Coatings

Standard Coating Protocol for Neuronal Cultures

This protocol is adapted from established methods for culturing ventral midbrain dopaminergic neurons and neural stem cells [39] [36].

- Surface Preparation: Begin with tissue culture-treated plates, glass coverslips, or other surfaces. For optimal laminin binding, a pre-coating with Poly-L-Lysine (PLL) or Poly-D-Lysine (PDL) is recommended. Incubate with the PLL/PDL solution for 1 hour at room temperature.

- Rinsing: A critical step. Rinse the surface thoroughly with sterile water three times to remove any residual toxic PDL [40].

- Laminin Coating Solution Preparation: Thaw a frozen laminin stock solution (e.g., 100 µg/mL) slowly on ice. Dilute it to a working concentration of 1-10 µg/mL in cold, sterile Dulbecco's Phosphate-Buffered Saline (DPBS). Using DPBS with calcium and magnesium (Ca²⁺/Mg²⁺) is preferable for maintaining protein structure [35].

- Coating Application: Add the diluted laminin solution to the prepared cultureware.

- Incubation: You have two options:

- Preparing for Cell Seeding: After incubation, carefully remove the excess laminin solution using a pipette. Do not rinse the coated surface, as this will remove the laminin layer. The surface is now ready for immediate cell seeding. If not used immediately, coated plates can be stored at +2°C to +8°C for up to 4 weeks, provided the surface does not dry out [35].

Workflow for Coating and Long-Term Culture

The following diagram visualizes the multi-step process for preparing a laminin-coated surface and maintaining a neuronal culture.

Laminin Signaling in Neuronal Survival and Maturation

Laminin promotes neuronal health and barrier function through specific molecular pathways. The diagram below illustrates the key signaling cascade triggered by laminin-integrin interaction, which is crucial for maintaining mature neuronal cultures.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents for Laminin-Based Cultures

| Reagent / Material | Function / Description | Example Usage |

|---|---|---|

| Recombinant Human Laminin | Defined, animal-origin-free, full-length protein; superior functionality and batch-to-batch consistency [35]. | Gold standard for clinical or translational research (e.g., Biolaminin CTG/MX grades) [35]. |

| Poly-D-/Poly-L-Lysine | Synthetic cationic polymer; enhances surface adhesion for subsequent laminin coating. | Pre-coating step to improve laminin binding and initial cell attachment [39]. |

| DPBS with Ca²⁺/Mg²⁺ | Diluent for laminin; divalent cations help maintain protein structure and function [35]. | Diluting laminin stock solution to working concentration for coating. |

| Integrin β1-Stimulatory Antibody | Research tool to activate integrin β1 receptors, mimicking laminin signaling [36]. | Experimental validation of laminin-integrin pathway mechanisms. |

| Epac Agonists | Pharmacological agents that activate the Epac/Rap1 pathway downstream of laminin [38]. | Enhancing barrier function and junction formation in epithelial/endothelial co-cultures. |

Frequently Asked Questions and Troubleshooting

Q1: My cells are not attaching properly to the laminin-coated surface. What could be wrong?

- Incorrect Coating Concentration: The laminin concentration may be too low. Try a variety of dilutions to optimize for your specific cell type. Some researchers use a 1:100 dilution of a stock solution with good results [40].

- Surface Incompatibility: While laminin is compatible with most surfaces (glass, plastic, hydrogels), tissue culture-treated plastic provides the best binding due to its negative charge [35]. Ensure you are using an appropriate surface.

- Protein Activity: Avoid repeated freeze-thaw cycles of the laminin stock solution. Thaw slowly on ice and store diluted aliquots. Biolaminin 521, for example, can undergo three freeze-thaw cycles without losing functionality [35].

Q2: I notice my neuronal cultures start to detach after several weeks. How can I improve long-term stability? For long-term cultures lasting several months, the laminin coating can degrade. A technique called "spiking" can help: add 1-5 µg/mL of additional laminin directly to the culture medium to replenish the coating and improve cell attachment [35].

Q3: Should I rinse the surface after removing the laminin coating solution? No. After removing the excess laminin solution, the coated surface should not be rinsed. Washing at this stage will remove the thin, functional layer of laminin you have just applied [35]. Proceed directly to seeding your cells.

Q4: My cells are dying shortly after plating. Could the coating be toxic?

- Check the Pre-coat: If you are using a PDL pre-coat, toxicity is a common culprit. Ensure you rinsed the PDL-coated surface three times with sterile water to remove any residual toxic monomer [40].

- Check Laminin Source and Storage: Use laminin from a reputable supplier and ensure it has been stored correctly. Avoid using laminin that has been subjected to stressful conditions.

Q5: What is the difference between tissue-derived and recombinant laminin? Tissue-derived laminins are impure mixtures of several ECM proteins and are degraded during isolation. Recombinant full-length laminins (e.g., Biolaminin) are chemically defined, animal-origin-free, and preserve all functional domains necessary for self-polymerization and proper cellular signaling, leading to more authentic and reproducible cell culture conditions [35].

Technical Comparison: Core Formulations and Performance

The choice between Neurobasal and BrainPhys Imaging (BPI) media fundamentally shapes the physiological relevance and experimental outcomes of neuronal cultures. The table below summarizes their core characteristics and performance metrics.

Table 1: Core Formulation and Performance Comparison

| Parameter | Neurobasal Medium | BrainPhys (BP) | BrainPhys Imaging (BPI) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Design Philosophy | Optimized for long-term neuron survival and minimal astrocyte growth [41] [42] | Formulated to support robust electrophysiological function and synaptic activity [43] [44] | Optimized from BP for live-cell imaging while maintaining physiological function [45] [46] |

| Key Components | High glucose (25 mM), high L-cysteine (260 µM) [41] [44] | Physiological glucose (2.5 mM), balanced neuroactive amino acids, and salts [43] [44] | BP base with phenol red removed and vitamins (e.g., riboflavin) adjusted [45] [47] |

| Osmolality | Not specified in results | ~300 mOsmol/L (matches human CSF) [45] | ~300 mOsmol/L (maintained from BP) [45] |

| Neuronal Activity | Supports baseline survival; yields low spontaneous spike rates (~0.5 Hz) in MEA recordings [42] [43] | Superior; leads to a higher proportion of synaptically active neurons and increased mean firing rates [43] | Equivalent to BP; optimally supports electrical and synaptic activity during imaging [45] [46] |

| Autofluorescence | High, especially at short excitation wavelengths (violet-blue) [45] [47] | High (contains light-reactive components) [45] | Dramatically reduced; as low as PBS across the visible light spectrum [45] [46] |

| Phototoxicity | High under prolonged light exposure, primarily due to riboflavin and other components [45] [47] | Present [46] | Minimized; healthy morphology maintained even after 12 hours of blue LED light exposure [46] |

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Challenges

FAQ: My fluorescent live-cell imaging has a high background. How can I improve my signal-to-noise ratio?

Challenge: High autofluorescence from culture medium components, such as phenol red and riboflavin, interferes with detection of fluorescent signals [45] [47].

Solution:

- Switch to a specialized imaging medium: Replace standard media with BrainPhys Imaging Medium. Its formulation eliminates phenol red and adjusts vitamin concentrations, resulting in autofluorescence levels similar to phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). This significantly enhances the signal-to-background ratio [45] [46].

- Validate with your dyes: BPI shows superior performance across the spectrum, with the most significant improvements in the blue (excitation/emission ~355/460 nm) and green (excitation/emission ~485/520 nm) channels [45].

FAQ: My mature neuronal cultures lack robust synaptic activity and network firing. What can I do?

Challenge: Traditional media like Neurobasal contain non-physiological concentrations of salts, neuroactive amino acids, and glucose, which can impair action potential generation and synaptic communication [43] [44].

Solution:

- Use a physiologically balanced medium: Transition cultures to BrainPhys or BrainPhys Imaging Medium. Its composition mirrors the cerebrospinal fluid, providing a more realistic extracellular environment. This promotes the development of a higher density of synapses and synaptic receptors (e.g., AMPA, NMDA, GABA), leading to increased spontaneous spike rates and network activity [42] [43].

- Supplement strategically: The addition of creatine (an energy precursor), cholesterol (for synaptogenesis), and estrogen (for calcium handling) to basal media can synergistically enhance spontaneous electrical activity [42].

FAQ: My neurons show signs of stress or death during long-term or light-intensive imaging sessions.

Challenge: Light-reactive components in culture media (e.g., riboflavin) can generate reactive oxygen species (ROS) upon illumination, leading to phototoxicity and cell death [45] [47].

Solution:

- Employ a low-phototoxicity medium: BrainPhys Imaging Medium is specifically designed to mitigate this issue. Its optimized formulation reduces the generation of cytotoxic products upon light exposure, thereby supporting neuronal viability during extended imaging [45] [46].

- Avoid medium freezing: Do not freeze media to extend shelf life, as this can cause precipitates of inorganic salts and amino acids that will not easily go back into solution and may stress cells [41].

Experimental Protocols for Media Transition and Validation

Protocol: Transitioning Primary Neuronal Cultures to BrainPhys

This protocol is optimized for maintaining the health and function of primary rodent neurons [43].

Workflow Diagram: Media Transition for Primary Neurons

Key Materials:

- Primary Neurons: e.g., Rat E18 cortical neurons.

- Initial Plating Medium: Neurobasal or NeuroCult Neuronal Basal Medium supplemented with appropriate supplements (e.g., B-27 or SM1) [43].

- Target Medium: BrainPhys or BrainPhys Imaging Medium, supplemented with SM1 Neuronal Supplement [43].

- Coating: Poly-D-lysine coated culture vessels [42].

Procedure:

- Plating: Plate dissociated primary neurons in the initial plating medium [43].

- Initial Culture: Maintain cultures for 5 days in vitro (DIV) without disturbance to allow for initial attachment and process outgrowth [43].

- Media Transition: On DIV5, perform a half-medium change, carefully removing half of the initial plating medium and replacing it with the pre-equilibrated BrainPhys (or BPI) medium supplemented with SM1 [43].

- Long-term Maintenance: Continue feeding the cultures by performing half-medium changes with the BrainPhys-based medium every 3 to 4 days [43] [44].