A Scientist's Guide to Preventing Contamination in Long-Term Neuronal Cultures

Maintaining sterile, uncontaminated long-term neuronal cultures is a critical yet challenging prerequisite for reliable neuroscience research and drug discovery.

A Scientist's Guide to Preventing Contamination in Long-Term Neuronal Cultures

Abstract

Maintaining sterile, uncontaminated long-term neuronal cultures is a critical yet challenging prerequisite for reliable neuroscience research and drug discovery. This article provides a comprehensive framework for researchers, from foundational principles of aseptic technique and common contaminants to advanced methodological protocols for primary and stem cell-derived cultures. It further delves into systematic troubleshooting, the integration of real-time quality control measures like live-cell imaging, and comparative validation strategies to ensure data integrity and reproducibility across experiments.

Understanding the Risks: Contaminants and Consequences in Neuronal Cultures

In long-term neuronal culture experiments, even a single contamination event can compromise months of painstaking research. Biological contaminants like bacteria, fungi, yeast, and mycoplasma compete with cells for nutrients, alter the biochemical environment, and can induce spurious cellular responses. For neuronal studies, which often extend over weeks or months to observe development, plasticity, and network formation, the risk and impact of contamination are magnified. Maintaining sterile conditions is paramount, as contaminated cultures can lead to unreliable data, wasted resources, and invalidated conclusions [1] [2]. This guide provides essential troubleshooting and FAQs to help you identify, prevent, and address the most common contaminants threatening your neuronal cultures.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. What are the most common sources of contamination in a cell culture lab? The most frequent sources are laboratory personnel, unfiltered air, contaminated reagents or cell stocks, and inadequately sterilized equipment [3]. In one estimate, up to 15% of U.S. cell cultures were contaminated with mycoplasma between the 1970s and 1990s, a problem that persists today [4].

2. Why should antibiotics not be used routinely in cell culture media? The continuous use of antibiotics encourages the development of antibiotic-resistant strains and can mask low-level, cryptic contaminations like mycoplasma. Once the antibiotic is removed, these hidden contaminations can bloom. Furthermore, some antibiotics may cross-react with cells and interfere with the cellular processes under investigation [5] [6].

3. My culture looks clear, but my neurons are behaving oddly. What could be wrong? You may have a mycoplasma contamination. Mycoplasmas are the smallest free-living organisms and, due to their lack of a cell wall and tiny size (~100 nm), they do not cause turbidity in the medium. However, they can attach to host cells, altering their metabolism, gene expression, and growth rates without obvious visible signs [4].

4. I've confirmed a contamination. What is the first thing I should do? Immediately isolate the contaminated culture from all other cell lines to prevent cross-contamination. Warn your labmates who share incubators or hood space. The contaminated vessel should be filled with a disinfectant like 10% bleach and then autoclaved before disposal [2] [5].

5. How can I best prevent cross-contamination by other cell lines? Always work with one cell line at a time in the biosafety cabinet. Thoroughly clean the hood before and after introducing a new cell line. Use filter tips to prevent aerosol contamination of your pipettors. Good labeling practices are also essential to avoid mix-ups [3] [5].

A Guide to Identifying Common Contaminants

Routine microscopic observation is your first line of defense. The table below summarizes the key visual and phenotypic characteristics of major contaminants.

Table 1: Identification Guide for Common Cell Culture Contaminants

| Contaminant | Visual Appearance (Microscopy) | Culture Medium pH | Other Key Identifiers |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bacteria [5] | Tiny, moving granules between cells. Turbidity (cloudiness). | Sudden drop (becomes acidic). | Visible turbidity, especially in advanced stages. |

| Yeast [3] [5] | Ovoid or spherical particles that may bud off smaller particles. Turbidity. | Stable initially, then increases (becomes basic) in heavy contamination. | Distinct, "yeasty" odor. |

| Fungi/Mold [3] [5] | Thin, wispy filaments (hyphae) or denser clumps of spores. | Stable initially, then increases (becomes basic) in heavy contamination. | Mycelia network visible under microscope. |

| Mycoplasma [5] [4] | No visible change. Cells may show subtle morphological changes or slowed growth. | No consistent change. | Requires specific tests: PCR, Hoechst staining, or ELISA. |

Troubleshooting and Decontamination Protocols

General Prevention: The Aseptic Technique Toolkit

The most effective strategy is prevention through rigorous aseptic technique [2] [6].

- Personal Protective Equipment (PPE): Always wear a lab coat (dedicated to the culture lab) and gloves [2].

- Biosafety Cabinet Management: Work in a serviced, properly functioning hood. Keep the surface uncluttered and clean it before and after use with 70% ethanol or isopropanol. Work well inside the hood and do not block air vents [2] [6].

- Disinfection: Spray EVERYTHING that enters the hood with 70% ethanol, including gloves, reagents, and equipment. Re-spray gloves every time you touch something outside the hood [2].

- Reagent and Labware Handling: Use sterile, certified reagents and labware. Aliquot media and sera to minimize repeated use of stock bottles. Filter media through 0.2 μm filters if sterility is in question [2] [5].

Table 2: Essential Reagents for Prevention and Control

| Research Reagent / Material | Function / Explanation |

|---|---|

| 70% Ethanol or Isopropanol [2] [6] | A disinfectant used to wipe down all surfaces and equipment entering the biosafety cabinet. The water content enhances efficacy. |

| Penicillin/Streptomycin [6] | A common antibiotic cocktail used to prevent bacterial contamination. Not recommended for long-term, continuous use. |

| Antimycotics [3] | Agents used to prevent or treat fungal and yeast contamination. |

| Poly-D-Lysine [7] [8] | A substrate coating used for primary neuronal cultures to promote cell attachment and growth. |

| Neurobasal Medium & B-27 Supplement [7] [9] | A defined, serum-free medium and supplement optimized for the long-term health and function of primary neurons. |

| HEPA Filter [3] | High-Efficiency Particulate Air filter used in biosafety cabinets to create a sterile work environment by removing contaminants from the air. |

| Mycoplasma Detection Kit (e.g., PCR-based) [6] [4] | Specific test to identify the presence of mycoplasma, which is invisible to the naked eye. |

Protocol for Mycoplasma Detection and Decontamination

Mycoplasma requires specialized protocols due to its elusive nature.

Detection Protocol (using commercial kits):

- Routine Testing: Test your cultures every few weeks using a commercially available kit. Common methods include PCR, enzymatic assays, or fluorescent staining with Hoechst stain [5] [4].

- Hoechst Staining Method: Fix the cells and stain with a DNA-binding dye like Hoechst. Under fluorescence microscopy, mycoplasma will appear as tiny, speckled fluorescence on the cell surface or in the background, unlike the clean, organized nuclear DNA of healthy cells [5].

Decontamination Protocol for Precious Cell Lines: If a valuable, irreplaceable neuronal line is contaminated, salvage may be attempted. Note: The safest practice is to discard contaminated cultures.

- Determine Antibiotic Toxicity: Dissociate and plate the contaminated cells in a multi-well plate with a range of anti-mycoplasma antibiotic concentrations (e.g., Plasmocin) [5] [4].

- Observe for Toxicity: Monitor cells daily for signs of toxicity like vacuolation, sloughing, or decreased confluency.

- Treat Cultures: Culture the cells for 2-3 passages using the antibiotic at a concentration one- to two-fold lower than the toxic level.

- Verify Eradication: Culture the cells in antibiotic-free medium for 4-6 passages and re-test for mycoplasma to confirm eradication [5].

Workflow for Suspected Contamination

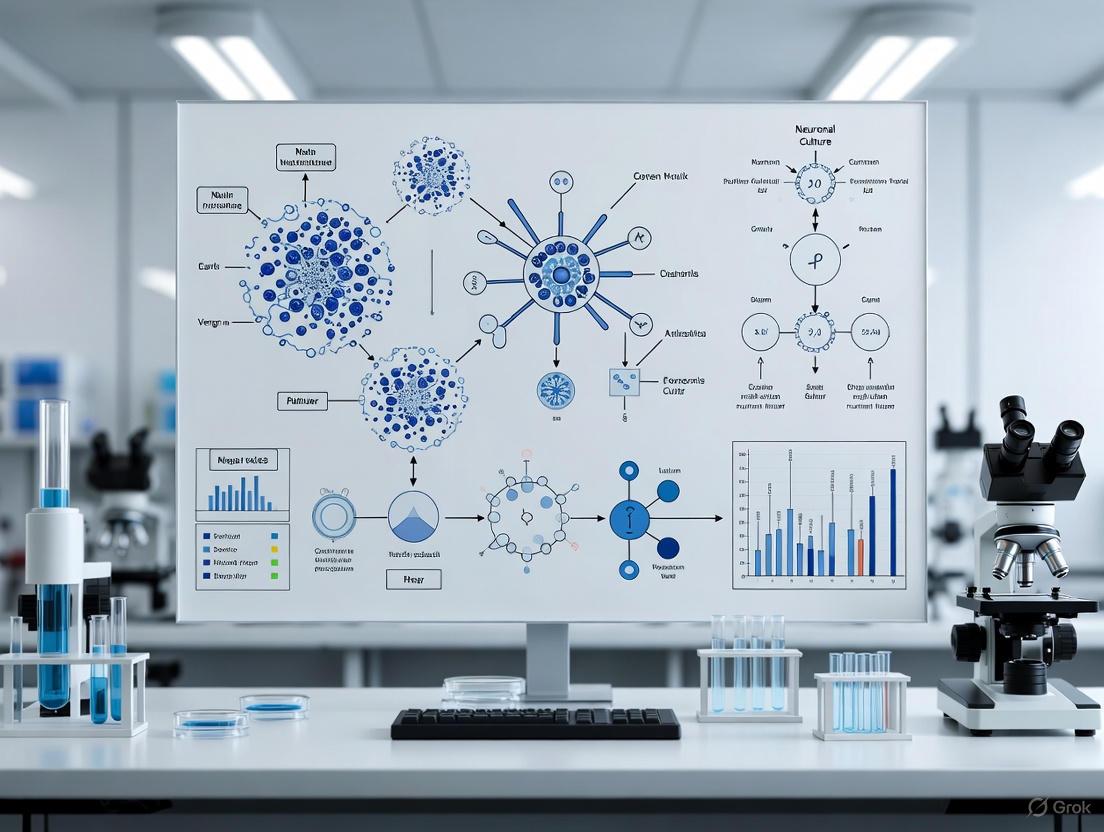

The following diagram outlines a logical workflow to follow when you suspect your culture is contaminated.

Special Considerations for Long-Term Neuronal Cultures

Primary neuronal cultures are particularly vulnerable over long durations. They are often grown in serum-free conditions, which eliminates the potential antimicrobial activity of serum, making them more susceptible [7] [8]. A significant but underappreciated threat to longevity is medium evaporation, which gradually increases osmotic strength and leads to a decline in cellular health [1]. To mitigate this in extended studies:

- Use Sealed Culture Dishes: Consider using culture dish lids that incorporate a gas-permeable, hydrophobic membrane. This selectively permits O₂/CO₂ exchange while drastically reducing water vapor loss, maintaining medium stability for many months [1].

- Maintain a Clean Incubator: Change the water in humidified incubators regularly and add a water bath treatment to prevent fungal growth. Clean the incubator interior frequently with a laboratory disinfectant [2] [6].

- Establish a Quarantine System: All new cell lines entering the lab should be placed in quarantine, tested for mycoplasma and other contaminants, and only introduced into the main facility after receiving a clean bill of health [6].

Mycoplasma contamination is a pervasive and often undetected problem in cell culture laboratories, with an estimated 15% to 35% of continuous cell lines affected worldwide [10] [11]. For researchers working with long-term neuronal cultures, this contamination poses a unique and significant threat. The absence of a cell wall, and their small size (0.1–0.3 µm), allows mycoplasmas to pass through standard sterilizing filters (0.22 µm) and persist invisibly in cultures, often without causing turbidity or immediate cell death [12] [13] [14]. Unlike common bacterial contaminants, mycoplasmas can subtly but profoundly alter host cell physiology, metabolism, and gene expression, jeopardizing the integrity of experimental data [10] [12]. Recent studies have shown that specific species, such as Mycoplasma fermentans, can not only infect and replicate within human neuronal cells but also induce necrotic cell death, accompanied by intracellular amyloid-β (1–42) deposition and hyperphosphorylation of tau, hallmarks of neurodegenerative disease pathways [15]. This technical support center provides a comprehensive guide to preventing, detecting, and eradicating this hidden menace to safeguard your neuronal research.

FAQs: Mycoplasma in Neuronal Cultures

1. Why is mycoplasma contamination particularly problematic for neuronal culture experiments? Mycoplasma contamination significantly impacts every aspect of cell biology. In neuronal research, the effects are especially devastating due to the long-term nature of the cultures and the sensitivity of neuronal function.

- Altered Physiology and Gene Expression: Mycoplasmas compete for essential nutrients with host cells, such as arginine, which can inhibit host cell growth and alter metabolic pathways [10] [12]. They can dysregulate hundreds of host genes, directly confounding gene expression studies in neuronal development and function [12].

- Induction of Necrotic Cell Death: Certain species, like M. fermentans, have been shown to infect and replicate in human neuronal cells (e.g., SH-SY5Y), leading to necrotic cell death rather than apoptosis. This is a critical distinction that can invalidate studies on neuroprotection and cell death pathways [15].

- Interference with Key Neurological Pathways: Contamination can lead to the degradation of critical signaling molecules or the induction of aberrant ones. For example, mycoplasmas can rapidly degrade extracellular amyloid-β (Aβ) peptides [11], while M. fermentans infection can induce intracellular Aβ1-42 deposition and phosphorylated tau, fundamentally disrupting research on Alzheimer's disease mechanisms [15].

2. What are the common sources of mycoplasma contamination in a cell culture lab? The primary sources are typically related to laboratory practices and materials [10] [14]:

- Contaminated Cell Lines: The most frequent source is infected cultures brought into the lab from other laboratories or cell banks.

- Laboratory Personnel: Human oral mycoplasmas (e.g., M. orale) can be introduced via aerosols from talking, coughing, or improper aseptic technique [10].

- Contaminated Reagents: While less common with reputable suppliers, animal-derived products like fetal bovine serum (FBS) can be a source of species like M. arginini and Acholeplasma laidlawii [10].

- Non-sterile Supplies and Equipment: Improperly sterilized media, reagents, or shared equipment in the incubator or water bath can harbor mycoplasmas.

3. My neuronal cells look healthy under a standard microscope. Can I still have a mycoplasma contamination? Yes, absolutely. This is the defining characteristic of the "hidden menace." Mycoplasmas are too small to be seen with a standard light microscope and do not typically cause the turbidity associated with bacterial infections. They can persist for long periods without noticeable cell death, all the while altering cellular functions invisibly [10] [16] [11]. Regular testing using dedicated methods is the only way to be certain your cultures are clean.

4. I have a contaminated, irreplaceable neuronal cell line. Can it be saved? Yes, eradication is often possible. The standard protocol involves treating the cells with a mycoplasma-specific antibiotic (e.g., Plasmocin at 25 µg/mL) for 1-2 weeks. Following treatment, cells must be cultured in antibiotic-free medium for 1-2 weeks and then re-tested to confirm successful eradication [12] [16]. For persistent cases, a second, longer treatment cycle may be necessary. The decision to treat should balance the value of the cells against the risk of the contamination spreading [16].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Inconsistent or Irreproducible Results in Neuronal Assays

Potential Cause: Mycoplasma contamination altering baseline cell metabolism and gene expression.

Solution:

- Test for Mycoplasma: Immediately test the suspect culture and any related stock cultures using a PCR-based method or a commercial detection kit [12] [16].

- Quarantine: Move the contaminated culture to a dedicated, quarantined incubator away from all other cell lines [16] [17].

- Assess Impact: Review recent experimental data from the contaminated line for anomalies. If possible, repeat critical experiments with a clean, backup stock.

- Eradicate or Discard: Decide whether to eradicate the contamination (for valuable lines) or discard the culture to protect other lines [16].

Problem: Unexplained Reduction in Neuronal Cell Viability or Necrotic Death

Potential Cause: Infection with a cytotoxic mycoplasma species such as M. fermentans.

Solution:

- Confirm Contamination: Use a DNA staining method (like Hoechst 33258) or PCR to confirm the presence and species of mycoplasma [18] [12].

- Investigate Mechanisms: If your research is focused on neurodegeneration, consider investigating specific pathways. Research indicates M. fermentans-induced necrosis may be mediated by IFITM3 upregulation and Aβ deposition [15]. Knocking down IFITM3 or amyloid precursor protein (APP) in a model system abolished this necrotic cell death [15].

- Eradicate Contamination: Treat the culture with an appropriate antibiotic regimen as described above.

Experimental Protocols for Detection and Analysis

Protocol 1: Rapid PCR-Based Detection of Mycoplasma Contamination

This method is sensitive, specific, and provides results within a few hours [12].

Research Reagent Solutions:

| Reagent/Material | Function |

|---|---|

| Cell culture supernatant | Source of potential mycoplasma DNA |

| PCR primers (Mycoplasma-F/R) | Amplify a conserved region of mycoplasma DNA |

| Taq Plus Master Mix | Enzymes and reagents for PCR amplification |

| Thermal cycler | Equipment to run PCR temperature cycles |

| Agarose gel equipment | To visualize PCR amplification products |

Procedure:

- Sample Collection: Culture cells for at least 12 hours. Transfer 200 µL of cell culture supernatant into a sterile tube.

- Heat Inactivation: Incubate the sample at 95°C for 5 minutes to inactivate nucleases. The sample can be stored at -20°C at this point [12].

- PCR Setup: Prepare a PCR master mix containing primers specific for mycoplasma (e.g., Forward: 5'-GGGAGCAAACAGGATTAGTATCCCT-3' and Reverse: 5'-TGCACCATCTGTCACTCTGTTAACCTC-3') [12].

- Amplification: Run the PCR using standard cycling conditions.

- Analysis: Separate the PCR products on a 1.5% agarose gel. A positive result is indicated by a band of the expected size (~500-600 bp), compared to positive and negative controls.

Protocol 2: Colocalization Staining for Visualizing Mycoplasma-Host Interaction

This method improves upon simple DNA staining by specifically identifying mycoplasma attached to the host cell membrane, reducing false positives from cytoplasmic DNA [18].

Procedure:

- Culture and Infect: Grow neuronal cells (e.g., SH-SY5Y) on coverslips. Infect with mycoplasma or use a contaminated culture.

- Staining: Simultaneously stain the cells with a fluorescent conjugate of Wheat Germ Agglutinin (WGA), which binds to the host cell membrane, and the DNA dye Hoechst [18].

- Fixation and Mounting: Fix the cells and mount the coverslips on slides.

- Microscopy: Observe under a fluorescence microscope. Mycoplasma contamination is confirmed by the colocalization of Hoechst (DNA) and WGA (membrane) fluorescence on the cell surface. This distinguishes adherent mycoplasma from apoptotic bodies or other DNA debris within the cytoplasm [18].

Data Presentation

Table 1: Impact of Key Mycoplasma Species in Neuronal Research

| Mycoplasma Species | Primary Source | Documented Impact on Neuronal Cells/Culture Systems |

|---|---|---|

| M. fermentans | Human | Infects and replicates in human neuronal cells (SH-SY5Y); induces necrotic cell death via IFITM3-mediated Aβ deposition and tau phosphorylation; invades brain organoids [15]. |

| M. hyorhinis | Swine | Degrades extracellular amyloid-β (Aβ) peptides in cell culture, leading to complete loss of detectable Aβ in medium and confounding Alzheimer's disease research [11]. |

| M. arginini | Bovine Serum | Competes for arginine, altering host cell metabolism and potentially inhibiting the growth and function of neuronal cells [10] [12]. |

| M. orale | Human | A common laboratory contaminant that can deplete arginine, potentially affecting metabolic studies in neuronal cultures [10]. |

Table 2: Comparison of Primary Mycoplasma Detection Methods

| Detection Method | Principle | Time to Result | Key Advantage | Key Limitation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PCR | Amplification of mycoplasma DNA | 3-4 hours [12] | High sensitivity and speed; can test many samples | Does not distinguish viable from non-viable mycoplasma |

| DNA Staining (Hoechst) | Fluorescent dye binding to DNA | 1-2 days | Visually shows infection location | Prone to false positives from host DNA debris [18] |

| Colocalization (Hoechst+WGA) | Co-staining of DNA and cell membrane | 1-2 days | High accuracy; distinguishes membrane-bound mycoplasma from host debris [18] | Requires fluorescence microscopy and analysis |

| Microbial Culture | Growth on specialized agar | Up to 4 weeks | "Gold standard"; confirms viability | Very slow; requires specific expertise [14] |

| ELISA | Detection of mycoplasma antigens | 1 day | Can test many samples | Lower sensitivity than PCR [14] |

Pathway and Workflow Visualizations

Pathway of M. fermentans-Induced Neurotoxicity

Mycoplasma Contamination Response Workflow

Cross-contamination in cell culture is a pervasive and often undetected problem that silently compromises experimental integrity, particularly in sensitive, long-term neuronal culture studies. This issue encompasses not only microbial invaders like bacteria, mycoplasma, and fungi but also the insidious cross-contamination of one cell line by another. When working with neuronal cultures, which often require months of maturation and study, the consequences of cross-contamination are magnified, potentially invalidating months of painstaking research and leading to the publication of irreproducible data. It is estimated that a startling number of published papers—roughly 16.1%—may be based on problematic cell lines, highlighting the critical need for vigilant contamination control practices [19]. This guide provides essential troubleshooting and foundational protocols to help researchers safeguard their work.

Troubleshooting Guide: Identifying and Addressing Contamination

How can I tell if my neuronal cell culture is contaminated?

Different contaminants present unique symptoms. The table below outlines common contaminants and their key identifiers.

| Contaminant Type | Visual/Microscopic Signs | Culture Medium Indicators | Additional Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bacteria [20] | Tiny, moving granules between cells; rods or spheres under high power. | Rapid turbidity (cloudiness); sudden, sharp drop in pH (yellow). | Can often be detected within a few days of infection. |

| Yeast [20] | Ovoid or spherical particles that may bud off smaller particles. | Turbidity in advanced stages; pH usually increases. | A eukaryotic contaminant that can be difficult to eradicate. |

| Mold [20] | Thin, wispy filaments (hyphae) or denser clumps of spores. | Turbidity; pH is stable initially, then increases. | Spores are resilient and can survive harsh conditions. |

| Mycoplasma [21] [20] | No visible change under standard microscopy. | No turbidity; subtle but chronic effects on cell health and metabolism. | Requires specific detection methods (e.g., PCR, Hoechst staining). Alters cell behavior without obvious signs [22]. |

| Cross-Contamination (by other cell lines) [19] [21] | Changes in typical growth pattern or morphology; unexpected behavior. | No direct change. | A misidentified or overgrown cell line can silently invalidate all data. STR profiling is required for definitive diagnosis. |

My culture is contaminated. What should I do now?

- Immediate Isolation: Immediately move the contaminated culture away from your other cell lines and primary cultures to prevent spread [20].

- Identification: Use the table above and further testing (e.g., PCR, staining) to identify the contaminant [20] [22].

- Disposal and Decontamination: Dispose of the contaminated culture according to your institution's biosafety protocols. Thoroughly decontaminate the incubator, biosafety cabinet, and any shared equipment with a laboratory disinfectant [20] [22].

- Root Cause Analysis: Investigate the source. Was there a break in aseptic technique? Are reagents or water contaminated? Is there a problem with the HVAC or HEPA filters? [20] [22].

How can I prevent cross-contamination with other cell lines in a shared lab space?

Preventing cross-contamination requires a multi-layered strategy:

- Good Aseptic Technique: Use dedicated media and reagents for each cell line whenever possible. Work with only one cell line at a time in the biosafety cabinet, and clean the workspace thoroughly between lines [22].

- Cell Line Authentication: Upon acquiring a new cell line, and at regular intervals during long-term studies (e.g., every 10 passages or before freezing a new stock), perform Short Tandem Repeat (STR) profiling to verify its identity [21] [23].

- Use Low-Passage Stocks: Start experiments with fresh, low-passage cells to minimize the risk of genetic drift and the accumulation of undetected contaminants [21].

- Check the Register: Before using a new cell line, consult the ICLAC Register of Misidentified Cell Lines to ensure you are not starting with a known-contaminated line [23].

What are the special considerations for preventing contamination in long-term neuronal cultures?

Long-term neuronal cultures, which can be maintained for over a year, face unique challenges [24]:

- Evaporation: Over months, medium evaporation increases osmotic strength, which is a major but underappreciated contributor to the gradual decline in neuronal health [24].

- Chronic, Low-Level Contamination: Contaminants that would quickly overgrow a short-term culture might persist at low levels, subtly altering neuronal function and plasticity over time.

- Solution: Using culture dishes sealed with a gas-permeable membrane (e.g., fluorinated ethylene-propylene) can drastically reduce evaporation and prevent airborne contamination, allowing for the study of long-term development and plasticity [24].

Troubleshooting workflow for a contaminated cell culture

Foundational Protocols for Contamination Control

Protocol 1: Cell Line Authentication by STR Profiling

Short Tandem Repeat (STR) profiling is the international gold standard for authenticating human cell lines. The following protocol is based on the ANSI/ATCC ASN-0002-2011 guidelines [23].

Key Materials:

- DNA purification kit

- STR PCR multiplex kit (e.g., Promega GenePrint 24 System) [23]

- Capillary Electrophoresis instrument

- Reference database (e.g., ATCC, DSMZ STR databases)

Methodology:

- DNA Extraction: Purify genomic DNA from your cell line of interest.

- Multiplex PCR: Amplify the recommended core STR loci using a commercial kit. The updated standard recommends 13 autosomal STR loci [23].

- Capillary Electrophoresis: Separate the amplified PCR products to determine the number of repeats at each locus, generating a unique DNA profile.

- Data Analysis: Compare the obtained STR profile to a reference profile from a certified cell bank (e.g., ATCC). A match of 80% or higher is generally considered acceptable for authentication, accounting for minor genetic drift in culture [23].

Protocol 2: Mycoplasma Detection by Hoechst Staining

Mycoplasma, which lack a cell wall, cannot be seen with standard microscopy. This fluorescence-based method is a reliable detection technique [21].

Key Materials:

- Cell culture free of antibiotics for at least one week

- Hoechst 33258 stain

- Fixative (e.g., Carnoy's fixative: methanol:glacial acetic acid 3:1)

- Fluorescence microscope with DAPI filter

Methodology:

- Seed Cells: Grow cells on a sterile glass coverslip in a culture dish until subconfluent.

- Fix Cells: Wash coverslip with PBS and fix cells with Carnoy's fixative for 5-10 minutes.

- Stain: Apply Hoechst 33258 stain (e.g., 1 µg/mL in PBS or buffer) for 15-30 minutes in the dark.

- Wash and Mount: Wash with deionized water and mount the coverslip on a microscope slide.

- Visualize: Observe under a fluorescence microscope at 500X magnification.

- Interpret Results: Mycoplasma-negative cells will show clean, stained nuclei only. Mycoplasma-positive cells will show characteristic patterns of extracellular, particulate, or filamentous fluorescence in the spaces between the nuclei [21].

Protocol 3: Long-Term Neuronal Culture Using Membrane-Sealed Chambers

This specialized protocol enables the maintenance of healthy primary neuronal cultures for over a year, crucial for studies of long-term plasticity and development [24].

Key Materials:

- Multi-electrode array (MEA) dish or other culture chamber

- Gas-permeable membrane (e.g., FEP film, 12.7 µm thick)

- PTFE (Teflon) ring and O-rings

- Non-humidified CO₂ incubator

Methodology:

- Chamber Fabrication: Fabricate a sealed chamber by placing a PTFE ring with a gas-permeable membrane over the MEA, secured with O-rings to create a gas-tight seal [24].

- Cell Culture: Plate dissociated neuronal cells (e.g., from rat embryo cortex) onto the substrate within the sealed chamber using standard primary culture techniques.

- Incubation: Place the sealed chambers in a standard, non-humidified incubator at 37°C with 5% CO₂.

- Medium Changes: Perform partial medium changes aseptically and infrequently, as the sealed system greatly reduces evaporation.

- Monitoring: The membrane allows for the free exchange of O₂ and CO₂ while being highly impermeable to water vapor, preventing hyperosmolality and blocking airborne pathogens [24].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents & Materials

| Item | Function/Application | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| STR Profiling Kit [23] | Authenticates human cell line identity by analyzing short tandem repeats. | Choose a kit that amplifies the core loci recommended by the ANSI/ATCC standard (e.g., GenePrint 24). |

| Hoechst 33258 Stain [21] | Fluorescent DNA dye used to detect mycoplasma contamination. | Stains extracellular mycoplasma DNA, revealing a characteristic particulate pattern between cells. |

| Gas-Permeable Membrane [24] | Seals culture dishes for long-term experiments. Permeable to O₂/CO₂, impermeable to water/microbes. | Enables long-term neuronal culture by preventing evaporation and contamination. |

| Mycoplasma Detection PCR Kit | A highly sensitive molecular method for detecting mycoplasma. | More sensitive than staining; can detect multiple mycoplasma species. |

| Non-Enzymatic Detachment Agent [19] | Gently detaches adherent cells without degrading surface proteins. | Crucial for preserving cell surface epitopes for subsequent applications like flow cytometry. |

| Defined Medium & Serum Alternatives | Supports cell growth without introducing unknown variables or contaminants. | Reduces risk of chemical and viral contamination from bovine serum. |

Three-pillar strategy for holistic contamination control

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

How often should I authenticate my cell lines?

You should authenticate cell lines [23]:

- Upon acquiring a new cell line.

- When generating a new master stock or freezing down for long-term storage.

- Before starting a new, important series of experiments.

- At regular intervals during long-term culture (e.g., every 10 passages).

- If you observe unexpected cell behavior or morphological changes.

Should I use antibiotics in my neuronal culture media routinely?

No. The continuous use of antibiotics is strongly discouraged [20]. It can mask low-level, chronic contaminations (especially mycoplasma), promote the development of antibiotic-resistant strains, and may have unintended cytotoxic or off-target effects on your neuronal cells, interfering with the very processes you are trying to study.

What is the most underappreciated cause of decline in long-term neuronal cultures?

Medium evaporation leading to hyperosmolality. While microbial contamination is an obvious culprit, the gradual increase in osmotic strength due to water evaporation is a major factor in the slow decline of neuronal health over weeks and months. This is especially critical in standard humidified incubators [24].

Our lab is setting up a new cell culture space. What is the single most important investment to prevent contamination?

While a biosafety cabinet is essential, a robust training program in aseptic technique for all users is the most critical investment. Human error is a primary source of contamination [22], and consistent, proper technique is the first and best defense. This should be complemented by a written lab policy on cell culture and contamination control [23].

Troubleshooting Guide: Common Environmental Contamination Issues

This guide helps diagnose and resolve contamination issues in long-term neuronal cultures related to environmental control failures.

| Observed Problem | Potential Causes | Corrective & Preventive Actions |

|---|---|---|

| Rapid pH drift in culture medium | Incubator CO² concentration is too high or too low, affecting the bicarbonate buffer system. [25] | Calibrate CO² sensor and controller. Ensure seals on incubator doors are intact. |

| Increased microbial growth (bacterial/fungal) | High humidity promoting condensation and microbial growth; contaminated water reservoir or air filter. [19] | Use sterile, distilled water in reservoirs. Clean and disinfect humidity pan regularly. Check HEPA filters for integrity. |

| Reduced neuronal viability or altered morphology | Sub-optimal temperature stress; incubator temperature set incorrectly or has large fluctuations. [26] | Independently verify incubator temperature with a calibrated thermometer. Ensure incubator is not placed in drafty areas. |

| Unexplained cellular stress or death | Accumulation of volatile organic compounds (VOCs) from cleaning agents or off-gassing materials inside the incubator. [19] | Avoid using volatile disinfectants inside the chamber. Use only incubator-safe materials and trays. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What are the optimal CO², temperature, and humidity setpoints for long-term mammalian neuronal culture?

For mammalian cells, including primary neurons, the standard incubator settings are 5% CO² and 37°C [26]. While often set at 95%, the key function of relative humidity is to prevent evaporation from culture media. The primary role of 5% CO² is to maintain a stable physiological pH (typically around 7.4) in bicarbonate-buffered media [19].

Q2: How can I verify that my incubator's environmental controls are functioning correctly?

Regular monitoring and calibration are essential.

- CO² Levels: Use a portable, calibrated CO² meter to periodically verify the incubator's internal sensor.

- Temperature: Place a traceable, independent thermometer inside the incubator to cross-check the set temperature, especially after door openings [26].

- Humidity: Manually check the water reservoir regularly to ensure it is filled with sterile water and cleaned to prevent microbial biofilm formation [19].

Q3: What is the most likely source of fungal contamination, and how can I prevent it?

The humidity water pan is a common source of fungal and bacterial contamination. To prevent this:

- Use only sterile, distilled water.

- Add a recommended amount of copper-based fungistatic agent to the water reservoir.

- Establish and follow a strict, regular schedule for cleaning and disinfecting the pan [19].

Q4: Beyond contamination, how can slight temperature variations impact my neuronal cultures?

Temperature is critical for optimal cell health and growth. Even small deviations from 37°C can cause thermal stress in mammalian neurons, potentially altering metabolic rates, gene expression, and synapse function. Consistent temperature is paramount for reproducible experimental results in sensitive long-term cultures [26].

The following table summarizes key environmental parameters and their typical roles in cell culture, synthesizing information from general guidelines and specific neuronal protocols.

| Parameter | Typical Setting for Mammalian Cells | Primary Function in Culture | Consequences of Deviation |

|---|---|---|---|

| CO² Concentration | 5% [26] | Maintains physiological pH in bicarbonate-buffered media. [19] | Too High: Medium becomes acidic. Too Low: Medium becomes basic; both impair cell health. |

| Temperature | 37°C [26] | Maintains optimal enzymatic activity and physiological function for mammalian cells. [26] | Too High: Induces thermal stress and cell death. Too Low: Slows metabolism and growth. |

| Relative Humidity | ~95% | Minimizes evaporation from culture media, preventing osmotic stress and concentration of toxic metabolites. [19] | Too Low: Excessive evaporation, leading to altered medium composition. Too High (poorly managed): Promotes condensation and microbial growth. |

Standard Protocol for Establishing Primary Neuronal Cultures

The workflow below outlines the critical steps for the isolation and initial plating of primary cortical or hippocampal neurons from rodent embryos, highlighting steps where environmental control is crucial [27] [9].

Key Considerations:

- Aseptic Technique: All steps must be performed under sterile conditions in a biosafety cabinet to prevent microbial contamination [19].

- Environmental Control during Dissection: Using ice-cold buffers during dissection helps maintain cell viability. The enzymatic digestion at 37°C requires a controlled water bath [27] [9].

- Incubator Stability: After plating, the consistent environment of the CO² incubator is critical for cell attachment, survival, and long-term differentiation over several weeks [26].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents for Primary Neuronal Culture

The following reagents are critical for the successful isolation and maintenance of primary neurons, as derived from established protocols [27] [9].

| Reagent / Material | Function / Purpose |

|---|---|

| Poly-L-Lysine | Coats culture surfaces to promote neuronal attachment and neurite outgrowth. |

| Papain Enzyme | Proteolytic enzyme used for gentle dissociation of neural tissue into single cells. |

| DNase I | Prevents cell clumping during dissociation by digesting DNA released from damaged cells. |

| Neurobasal Medium | A serum-free medium formulation optimized for the long-term survival of postnatal and embryonic neurons. |

| B-27 Supplement | A defined supplement essential for neuronal growth and health, used in Neurobasal medium. |

| Hank's Balanced Salt Solution (HBSS) | An isotonic salt solution used during tissue dissection and washing to maintain osmotic balance. |

Environmental Impact on Cellular Physiology

The laboratory environment can directly influence cellular physiology. The diagram below illustrates the documented causal pathways through which temperature, humidity, and CO² can impact both the cultured cells and introduce experimental variables.

This technical support guide addresses the unique challenges and vulnerabilities encountered when using primary and immortalized neuronal cultures in long-term experiments. A critical, often overlooked, vulnerability in extended studies is the risk of microbial contamination and cellular drift, which can compromise data integrity. Understanding the inherent strengths and weaknesses of each model system is essential for designing robust experiments and accurately troubleshooting issues. This resource provides comparative data, detailed protocols, and frequently asked questions to support researchers in maintaining the health and validity of their neuronal cultures over time.

The table below summarizes the core vulnerabilities of primary and immortalized neurons, with a specific focus on factors critical for long-term experimental design.

Table 1: Key Vulnerabilities in Long-Term Experiments for Primary vs. Immortalized Neurons

| Vulnerability Factor | Primary Neurons | Immortalized Neuronal Cell Lines (e.g., SH-SY5Y, PC12) |

|---|---|---|

| Inherent Biological Relevance | High; retain native morphology, signaling, and electrophysiology [28] [7] [29]. | Low to moderate; often cancer-derived, exhibit immature features, and lack definitive synapses [30] [7] [29]. |

| Proliferation & Longevity | Limited lifespan; post-mitotic, undergo senescence, restricting long-term studies [28] [7]. | Unlimited proliferation; suitable for extended passaging but prone to genetic drift over time [30] [29]. |

| Phenotypic Stability | Batch-to-batch variability; phenotype and function can vary between isolations [28]. Morphology and health decline after purification, requiring rapid experimentation [28]. | Phenotypic drift; poor differentiation and lack of mature neuronal markers are common [7] [29]. |

| Contamination Risk Duration | High risk throughout a finite culture period; valuable due to difficult and expensive isolation [28]. | High risk over indefinite culture duration; frequent handling for passaging increases exposure opportunities. |

| Functional Validation in Culture | Form dense networks, exhibit spontaneous and evoked synaptic activity, and demonstrate mature action potentials [31] [7]. | Often lack consistent expression of key ion channels and receptors, limiting functional neurophysiological studies [30]. |

Experimental Protocols for Isolation and Culture

Protocol 1: Tandem Immunomagnetic Isolation of Microglia, Astrocytes, and Neurons

This protocol allows for the sequential isolation of multiple cell types from a single brain tissue sample, maximizing data yield and comparative potential [28].

- Tissue Dissection and Dissociation: Fresh brain tissue is carefully dissected. The meninges are removed, and the desired region is mechanically disrupted and enzymatically digested with trypsin to create a single-cell suspension. The protease is inactivated, and the homogenate is filtered and centrifuged to remove debris [28].

- Sequential Immunomagnetic Separation:

- Microglia Isolation: Incubate the cell suspension with magnetic beads conjugated to an anti-CD11b antibody. Place the mixture in a magnetic field to retain CD11b+ microglial cells. Collect the negative fraction for the next step [28].

- Astrocyte Isolation: Take the CD11b-negative cell fraction and incubate it with magnetic beads conjugated to an anti-ACSA-2 antibody. Use a magnetic field to isolate ACSA-2+ astrocytes [28].

- Neuron Isolation (by negative selection): The remaining cell suspension (CD11b/ACSA-2 negative) is incubated with a biotin-antibody cocktail that targets non-neuronal cells. These labeled cells are then depleted using magnetic beads, resulting in a purified neuronal population [28].

- Critical Considerations: This protocol is highly sensitive to the age of the animal source. Isolated cells, particularly neurons, can begin to change morphology shortly after purification, so subsequent experiments should be performed as quickly as possible [28].

Protocol 2: Isolation and Culture of Functional Adult Human Neurons

This protocol is designed for neurosurgical specimens and yields functional adult human neurons, a highly relevant but challenging model [31].

- Sample Collection and Transport: Surgically excised brain tissue is transported to the laboratory in an ice-cold protective transport medium, often Hibernate-A, supplemented with B-27 and a ROCK inhibitor (Y-27632) to enhance cell survival [31].

- Mechanical and Enzymatic Dissociation: The grey matter is dissociated into small pieces and then digested with papain (2.5 U/ml) and DNase I (100 U/ml) for 20 minutes at 37°C with gentle rotation. The digestion is halted with an equal volume of transport medium, and the tissue is gently triturated. The cell suspension is passed through a cell strainer and centrifuged [31].

- Plating and Long-Term Maintenance: The cell pellet is resuspended in a neuronal growth medium (e.g., DMEM/F12) supplemented with B-27, GlutaMAX, antibiotics, heparin, a ROCK inhibitor, and a cocktail of neurotrophic factors (NGF, BDNF, NT-3, GDNF, IGF-1). Cells are plated onto poly-D-lysine-coated surfaces. Fifty percent of the culture medium is exchanged every 24 hours for the first 48 hours to remove debris, and then every 3-4 days thereafter [31].

Troubleshooting Guides and FAQs

Contamination Prevention and Management

Q: What are the best practices to prevent bacterial contamination in long-term neuronal cultures? A: Bacterial contamination can ruin precious samples. Key prevention strategies include:

- Aseptic Technique: Strict adherence to sterile technique is the first line of defense.

- Environmental Monitoring: New technologies, such as total volatile organic compound (TVOC) sensors, can be placed inside incubators to provide early detection of bacterial contamination within hours of onset, allowing for quick intervention [32].

- Antibiotic Use: While antibiotics can be used, their efficacy may wane over long-term culture, and they can mask low-level contamination. Their use should be validated for each experiment.

- Equipment Decontamination: Regularly clean incubators and work surfaces with 70% ethanol or a 10-15% bleach solution (made fresh weekly). Dedicate separate equipment (e.g., pipettes) for pre- and post-amplification areas if PCR work is also conducted in the lab [33].

Q: How can I address cellular "contamination" (e.g., overgrowth of glial cells in primary neuronal cultures)? A: The overgrowth of non-neuronal cells is a common issue in long-term primary cultures.

- Chemical Suppression: Use antimitotic agents like 5-Fluoro-2'-deoxyuridine (FdU) or cytosine arabinoside (Ara-C) to inhibit the division of glial cells after the neurons have been plated [7].

- Defined Media: Employ serum-free, defined media (e.g., Neurobasal Medium supplemented with B-27) that are optimized for neuronal survival and suppress glial proliferation [7] [34].

- Immunopanning/Purification: Start with a highly purified neuronal population using immunomagnetic separation (as in Protocol 1) or immunopanning techniques, which can achieve 95-99% purity for specific cell types [28] [7].

Culture Health and Phenotypic Stability

Q: My primary neurons are deteriorating before my long-term experiment is complete. What can I do? A: Primary neurons have a finite lifespan, but their health can be extended.

- Optimized Media Systems: Use advanced culture systems like the B-27 Plus Neuronal Culture System, which has been shown to support the survival of primary rat cortical neurons for up to four weeks in culture [34].

- Supportive Coating: Ensure cells are plated on a consistent, high-quality substrate like poly-D-lysine or poly-L-ornithine, often with laminin, to promote strong attachment and neurite outgrowth [7].

- Trophic Support: Supplement media with a cocktail of neurotrophic factors (BDNF, GDNF, etc.) as used in the adult human neuron protocol to provide ongoing metabolic and survival support [31].

Q: How can I ensure my immortalized neuronal cell lines are expressing a mature, neuronal phenotype for long-term differentiation studies? A: Immortalized lines often require induction to differentiate.

- Differentiation Agents: Treat cells with agents like retinoic acid (for SH-SY5Y and NT2 cells) or nerve growth factor (NGF, for PC12 cells) to promote a more neuronal phenotype [7] [29].

- Functional Validation: Do not rely on morphology alone. Validate the mature phenotype using functional assays (e.g., electrophysiology to check for action potentials) and confirm the expression of mature neuronal markers like MAP2, NeuN, and synaptophysin via immunocytochemistry [7] [29].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 2: Key Reagents for Neuronal Cell Culture

| Reagent/Material | Function | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| B-27 Supplement | Serum-free supplement providing hormones, antioxidants, and proteins to support neuronal survival. | Essential component in Neurobasal Medium for long-term culture of primary neurons, minimizing glial growth [34]. |

| Neurobasal Medium | Optimized, serum-free medium formulated for the long-term survival and health of hippocampal and cortical neurons. | The base medium for culturing cryopreserved primary rodent neurons [34]. |

| Poly-D-Lysine | Synthetic polymer coating for culture surfaces that enhances attachment of neuronal cells. | Coating plates or coverslips to ensure primary neurons adhere properly and extend neurites [7] [34]. |

| Papain | Proteolytic enzyme used for gentle dissociation of neural tissues without significantly damaging cell surface proteins. | Enzymatic digestion of adult human neurosurgical specimens to create single-cell suspensions [31]. |

| ROCK Inhibitor (Y-27632) | A small molecule that inhibits Rho-associated kinase, reducing apoptosis and improving cell survival after dissociation and plating. | Added to transport and plating media for adult human neurons to increase viability post-thaw and post-dissociation [31]. |

| Neurotrophic Factor Cocktail | A mix of growth factors (e.g., BDNF, GDNF, NGF, IGF-1) that support neuronal development, survival, and synaptic function. | Critical for maintaining the health and function of hard-to-culture cells like adult human neurons over weeks in vitro [31]. |

Experimental Workflow and Decision Pathway

The following diagram illustrates the key decision points and workflows for selecting and maintaining neuronal models in long-term experiments, integrating critical steps for contamination prevention.

Decision Workflow for Long-Term Neuronal Culture

Signaling Pathways in Neuronal Health and Contamination Response

While not a classic signaling pathway, the cellular response to contamination involves a critical shift in cellular priorities and stress pathways, which is crucial to understand in the context of long-term culture health.

Cellular Stress Response to Contamination

Proactive Defense: Establishing Rigorous Aseptic Protocols and Culture Practices

For researchers working with long-term neuronal cultures, mastering sterile technique is not just a best practice—it is a critical determinant of experimental success. Neuronal experiments often extend over weeks or months, providing continuous opportunity for microbial contamination that can compromise intricate electrophysiological measurements, calcium imaging, and molecular analyses. This guide provides essential troubleshooting and FAQs to help you maintain the aseptic environment required for the integrity of your valuable neuronal research.

Fundamental Principles of Asepsis

Sterile technique involves creating a barrier between your neuronal cultures and the non-sterile environment. Two key concepts form the foundation of this practice [35]:

- Sterile Technique: Aims to eliminate all microorganisms from a space or item. This is typically achieved before an experiment begins, such as when sterilizing equipment or preparing a biosafety cabinet.

- Aseptic Technique: Focuses on maintaining sterility by not introducing contamination to a previously sterilized environment during experimental procedures.

For neuronal cultures, which are particularly sensitive to subtle environmental changes, both techniques are equally important. Even minor contamination can alter neurite outgrowth, synapse formation, and overall network activity.

Proper Use of the Biosafety Cabinet

The biosafety cabinet (BSC) is your primary defense against contamination. Proper setup and operation are non-negotiable for neuronal culture work.

Cabinet Setup and Maintenance

- Location: Place your BSC in an area free from drafts, doors, windows, and through traffic [35].

- Operation: Leave the BSC running continuously, turning it off only when not in use for extended periods [35].

- Maintenance: Schedule regular professional servicing and certification to ensure proper HEPA filter function and airflow [2].

Work Practices Within the BSC

- Surface Disinfection: Thoroughly wipe all interior surfaces with 70% ethanol before and during work, especially after any spillage [35] [2].

- Work Area Organization: Keep the work surface uncluttered, containing only items required for your immediate procedure [35].

- Airflow Management: Do not block the front and rear grates, as this disrupts the protective air curtain [36] [2].

- UV Light Use: Utilize ultraviolet light to sterilize the interior and exposed surfaces between uses, but never while working [35].

Workflow Diagram for Sterile Technique in Neuronal Culture

The following diagram outlines the critical decision points and sequential steps for maintaining sterility throughout neuronal culture experiments.

Personal Protective Equipment (PPE) Protocols

PPE creates a crucial barrier that protects both your neuronal cultures from personal contamination and you from potential biohazards [35].

Essential PPE for Neuronal Culture

- Gloves: Wear appropriate gloves and disinfect them with 70% ethanol frequently during work, especially after touching any non-sterile surface [35] [2].

- Lab Coats: Use dedicated lab coats worn only in the cell culture laboratory and have them cleaned regularly [2].

- Additional Protection: For certain procedures or hazardous materials, additional protection such as safety glasses, face shields, or sleeves may be necessary [35] [37].

Proper Glove and Gown Technique

- Perform proper hand hygiene before donning gloves [35].

- Change gloves when contaminated and dispose of them properly with other contaminated laboratory waste [35].

- Avoid touching personal items, skin, or hair while wearing gloves.

Troubleshooting Common Contamination Issues

Even with careful technique, contamination can occur. This table helps identify and address common problems in neuronal culture work.

| Problem & Signs | Likely Cause | Immediate Action | Corrective & Preventive Measures |

|---|---|---|---|

| Rapid medium turbidity/yellowing.Microscope: moving bacterial cells [38]. | Introduction of bacteria via non-sterile surfaces, reagents, or poor technique [35]. | Discard contaminated culture. Disinfect incubator and work area [38]. | Review aseptic technique. Check reagent sterility. Use antibiotics with caution and only for precious cultures [36] [38]. |

| Floating clumps or filaments in medium.Microscope: hyphal structures or budding cells [38]. | Fungal or yeast spores from the environment, water baths, or unfiltered air [39]. | Discard culture immediately. Clean incubator with strong disinfectant (e.g., benzalkonium chloride). Add copper sulfate to water pan [38]. | Improve lab cleaning. Change water bath water regularly. Ensure proper BSC airflow. Use sterile, filtered tips [2] [39]. |

| Subtle, slow cell growth.Abnormal morphology.No medium color change [36] [38]. | Mycoplasma contamination, often from human skin, sera, or other contaminated cell lines [36]. | Confirm with a detection kit (e.g., PCR, DNA staining). Treat with removal agent or discard [36] [38]. | Quarantine new cell lines. Test for mycoplasma regularly (every 1-2 months). Use good personal hygiene practices [36] [38]. |

| Unexplained cell death or altered growth patterns without visible microbes [36]. | Chemical contamination from endotoxins, detergent residues, or impure water [36] [39]. | Identify and replace contaminated stock (media, water, etc.). | Use high-purity, lab-grade water. Source reagents from certified suppliers. Rinse reusable glassware thoroughly [36] [39]. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: Can I use antibiotics routinely in my neuronal culture media to prevent contamination? No, routine use of antibiotics is not recommended. While they might seem like a safety net, they can:

- Mask low-level contamination, particularly mycoplasma [36].

- Promote the development of antibiotic-resistant strains [36].

- Have toxic effects on certain sensitive neuronal cells and alter gene expression profiles [36]. Antibiotics should be used strategically, not as a substitute for proper aseptic technique.

Q2: How often should I clean my CO₂ incubator, and what is the best method? Incubators should be cleaned regularly according to the manufacturer's protocol [2].

- Weekly: Replace the humidifying water with sterile distilled water and consider adding a copper sulfate solution to inhibit fungal and bacterial growth [38].

- Monthly (or upon spillage): Thoroughly decontaminate all interior surfaces, shelves, and chambers with a recommended disinfectant (e.g., 70% ethanol, followed by a stronger sporicidal agent if needed) [35] [39]. Using incubators with automatic high-temperature sterilization cycles can significantly reduce this contamination risk [2].

Q3: I suspect my culture is contaminated, but I can't see anything under the microscope. What should I do? Some contaminants are not visible with standard microscopy. You should:

- Test for mycoplasma: Use a commercial detection kit based on PCR, DNA staining (e.g., Hoechst or DAPI), or microbial culture. This is a common culprit for "invisible" contamination [36].

- Check for chemical contaminants: Review your media and reagent sources, including water purity and potential endotoxin contamination [36] [39].

- Inspect culture behavior: Look for secondary signs like altered metabolism, slowed growth, or abnormal neuronal morphology [36].

Q4: What is the single most important step to prevent cross-contamination between my different neuronal cell lines? The most critical practice is to never use the same pipette or tip for different cell lines or reagent bottles [35] [2]. Always use sterile, disposable pipettes and filter tips a single time. Furthermore, obtain cell lines from reputable banks, periodically authenticate them, and maintain clear, accurate labeling on all flasks and vials to prevent misidentification [39].

Essential Reagent and Material Solutions

Using high-quality, sterile materials is fundamental to preventing contamination in neuronal culture.

| Item | Function & Importance in Neuronal Culture | Sterility & Handling Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Sterile Filter Tips | Prevent aerosol contamination of pipettors, protecting reagents and cultures from cross-contamination [2]. | Use always. Ensure filter is present. Change after each single use. |

| 70% Ethanol | Primary disinfectant for gloves, work surfaces, and the outside of all containers entering the BSC [35] [2]. | Solution must be 70% for optimal efficacy. Use liberally in spray bottles with lint-free wipes. |

| Sterile Serological Pipettes | For accurate, sterile transfer of media and other liquids. Cotton plugs prevent contamination of the pipette controller [36]. | Use only once. Avoid contact between the tip and any non-sterile surface. |

| High-Quality Media & Serum | Provides nutrients and growth factors essential for neuronal health and network development. | Purchase sterile, tested for endotoxins and viruses. Aliquot upon receipt to preserve sterility of the main stock [2] [39]. |

| Sterile Plasticware (flasks, plates) | Provides the sterile physical environment for cell growth. | Purchase pre-sterilized. Wipe exterior with ethanol before placing in BSC. Do not leave uncovered [35] [2]. |

Quarantine Procedures for New Cell Lines and the Importance of Mycoplasma Testing

Core Principles for a Contamination-Free Lab

Introducing new cell lines into your laboratory is a common source of biological contamination, particularly from mycoplasma, which can severely impact neuronal physiology and the reproducibility of long-term culture experiments. A robust quarantine procedure is not just a recommendation; it is the foundation of reliable neuroscience research and drug development.

All new cell lines should be treated as potentially contaminated until proven otherwise. Key principles include:

- Physical Separation: A dedicated quarantine room or incubator is essential to prevent cross-contamination with existing cultures [40] [16].

- Rigorous Testing: Mandatory authentication and mycoplasma testing must be completed before a cell line is moved into main culture areas [40] [21].

- Aseptic Technique: Meticulous technique and the use of personal protective equipment (PPE) are critical, as laboratory personnel are a major source of mycoplasma [40] [41].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) and Troubleshooting

What is the basic quarantine workflow for a new cell line?

The following diagram outlines the critical path every new cell line should follow, from arrival to full integration into your research.

Why is mycoplasma such a major concern for neuronal cultures?

Mycoplasma contamination is particularly problematic because it is not visible to the naked eye and does not cause media turbidity [41]. Its effects, however, are profound. Mycoplasma can alter cell metabolism, gene expression, and viability [42] [41]. In the context of long-term neuronal cultures, which are highly sensitive to their environment, these changes can compromise studies on synaptic function, network activity, and neuropharmacology, leading to irreproducible results [1] [43].

How can I prevent mycoplasma contamination in the first place?

Prevention is always better than cure. Key practices include:

- Quarantine All New Lines: Never place a newly acquired cell line directly into your main incubator [16] [41].

- Maintain Aseptic Technique: Use a clean lab coat and gloves, and spray all items with 70% ethanol before introducing them into the biosafety cabinet [40] [16].

- Avoid Routine Antibiotics: Using standard antibiotics like penicillin/streptomycin can mask bacterial contamination and is ineffective against mycoplasma, which lack a cell wall [41].

- Regularly Clean Equipment: Follow a strict schedule for cleaning incubators, water baths, and biosafety cabinets [40] [16].

My cell culture is contaminated with mycoplasma. What should I do?

If a test returns positive, act immediately to prevent a lab-wide outbreak.

- Quarantine: Immediately move the contaminated culture to a designated quarantine area [16].

- Decontaminate: Discard the culture and media by autoclaving. Decontaminate the incubator and hood used for the culture [40].

- Salvage (if essential): If the cell line is irreplaceable, treatment with specific anti-mycoplasma antibiotics (e.g., Plasmocin at 25 µg/mL for 1-2 weeks) can be attempted [16]. After treatment, maintain the cells without antibiotics for 1-2 weeks and re-test to confirm eradication [16].

Essential Testing Methodologies

A comprehensive quarantine protocol relies on proven testing methods to ensure cell line identity and purity.

Mycoplasma Detection Methods

| Method | Principle | Key Advantage | Key Disadvantage |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hoechst Staining [21] | Fluorescent DNA-binding dye stains extracellular mycoplasma. | Relatively easy and low-cost. | Requires fluorescence microscopy; subjective interpretation. |

| PCR-Based Detection [42] | Amplification of mycoplasma-specific DNA sequences. | Highly sensitive and rapid; many commercial kits available. | Cannot distinguish between viable and dead organisms. |

| Microbiological Culture [41] | Growth of mycoplasma in specialized broth and agar. | Considered the "gold standard"; highly sensitive. | Very slow (can take up to 4 weeks). |

| Enzymatic Assay | Detects enzymatic activity specific to mycoplasma. | Can be performed using a spectrophotometer. | Less common; may have lower specificity. |

Cell Line Authentication Methods

| Method | Application | Key Detail |

|---|---|---|

| STR (Short Tandem Repeat) Profiling [21] [42] | Identity verification of human cell lines. | Establishes a unique DNA "fingerprint" for a cell line; gold standard for human cells. |

| Isoenzyme Analysis [21] | Species verification. | Uses electrophoretic mobility of enzymes to confirm the species of origin. |

| Karyotyping [40] [42] | Genetic stability. | Analyzes chromosomal number and structure; can detect gross genetic changes. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

The following reagents and materials are critical for implementing effective quarantine and testing procedures.

| Reagent/Material | Function in Quarantine & Testing |

|---|---|

| Plasmocin [16] | Antibiotic used to treat mycoplasma-contaminated cultures (used at 25 µg/mL). |

| Hoechst 33258 [21] | Fluorescent dye used for DNA-staining method of mycoplasma detection. |

| Bacdown Detergent [40] | A disinfectant used for cleaning biosafety cabinets and wiping down incubators. |

| Mycoplasma Detection Kits (e.g., MycoProbe) [40] | Commercial kits that provide optimized reagents for reliable mycoplasma testing. |

| Quarantine Incubator [40] | A physically separate incubator used to house all new cell lines during the testing period. |

| Neurobasal Medium & B-27 Supplement [9] | Specialized medium and supplement optimized for the long-term health of neuronal cultures. |

| STR Profiling Kits [21] | Commercial kits containing primers and reagents for authenticating human cell lines. |

FAQs: Antibiotic Use in Neuronal Cultures

1. Should I always use antibiotics in my primary neuronal cultures?

No, for long-term neuronal cultures intended for electrophysiological or genomic studies, avoiding antibiotics is generally recommended. Research shows that common supplements like penicillin/streptomycin can alter the intrinsic electrical activity of neurons, including depolarizing the resting membrane potential and reducing firing frequency [44]. Furthermore, genome-wide studies indicate that penicillin-streptomycin treatment can significantly alter gene expression and regulatory pathways in cultured cells, which could confound your research results [45].

2. If I don't use antibiotics, how can I prevent bacterial contamination?

Prevention is the most effective strategy. This involves strict aseptic technique, regular cleaning and disinfection of workbenches and incubators, using sterile reagents and equipment, and ensuring proper training for all laboratory personnel [46] [19]. Creating a dedicated and clean cell culture environment is more effective than relying on antibiotics to control contamination.

3. What are the signs that my neuronal culture is contaminated?

Contamination can be detected through several observable characteristics [46]:

- Bacterial Contamination: The culture medium becomes turbid and may change color (often to yellow) due to a shift in pH. Under a microscope, you may observe tiny black, moving particles.

- Fungal Contamination: Visible filamentous structures (hyphae) or spots appear on the surface of the medium.

- Mycoplasma Contamination: The medium turns yellow prematurely, cell growth slows significantly, and massive cell death can occur at later stages. Mycoplasma often requires specific detection methods like PCR or fluorescence staining.

4. My culture is contaminated. What should I do?

The standard advice is to discard contaminated cultures immediately to prevent cross-contamination of other cells [46]. For extremely valuable cells, treatment with high concentrations of specific antibiotics (e.g., penicillin/streptomycin for bacteria, amphotericin B for fungi) can be attempted, but success is not guaranteed, and the recovered cells may have altered properties [46].

Troubleshooting Guides

Guide 1: Decision Workflow for Antibiotic Use

This diagram outlines the key considerations for deciding whether to include antibiotics in your neuronal culture media.

Guide 2: Identifying and Addressing Common Contamination

Use this table to quickly identify the type of contamination and appropriate response actions.

| Contamination Type | Key Identifying Characteristics | Recommended Action |

|---|---|---|

| Bacterial [46] | Medium turbidity; color change to yellow/brown; microscopic moving black dots. | Disculture culture. Decontaminate equipment. Review aseptic technique. Use antibiotic shock treatment only for critical cells. |

| Fungal [46] | Visible filamentous, wool-like structures; white spots or yellow precipitates in medium. | Disculture culture. Thoroughly clean incubator and workbench. Use antifungals (e.g., Amphotericin B) only if necessary. |

| Mycoplasma [46] | Premature yellowing of medium; slowed cell growth; abnormal cell morphology. | Disculture culture. Use validated detection methods (e.g., PCR). Source new cells from reputable banks. Use specific antibiotics (e.g., tetracyclines) for treatment with caution. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents for Neuronal Culture

This table details key reagents used in the optimized isolation and culture of primary neurons, based on established protocols [9] [47].

| Reagent / Material | Function / Purpose |

|---|---|

| Neurobasal Medium [47] | A serum-free medium optimized for neuronal survival and growth, helping to minimize the overgrowth of glial cells. |

| B-27 Supplement [9] [47] | Provides essential hormones, antioxidants, and proteins to support long-term neuronal health and function. |

| Poly-D-Lysine (PDL) / Poly-L-Lysine (PLL) [47] | Coating substrates that provide a positively charged surface to which neurons readily adhere. PDL is more resistant to protease degradation. |

| Papain [47] | A gentle enzyme used for tissue dissociation; considered an alternative to trypsin to avoid potential RNA degradation or cell damage. |

| L-Glutamine or GlutaMAX [9] [47] | A crucial amino acid that serves as a building block for proteins and a component in cellular energy metabolism. GlutaMAX is a more stable dipeptide. |

| Cytosine Arabinoside (AraC) [47] | An anti-mitotic agent used at low concentrations to inhibit the proliferation of glial cells, thereby maintaining higher neuronal purity. Use with caution due to potential neurotoxic effects. |

| Penicillin/Streptomycin [9] | A common antibiotic mixture used to prevent bacterial contamination. Its use should be justified, as it can alter neuronal electrophysiology and gene expression [44] [45]. |

Experimental Data: Quantifying Antibiotic Effects on Neurons

The following table summarizes quantitative findings from a study investigating the specific effects of penicillin/streptomycin on the electrophysiological properties of rat hippocampal pyramidal neurons [44]. This data underscores why antibiotic-free culture is critical for electrophysiology research.

| Electrophysiological Parameter | Change with Penicillin/Streptomycin | Statistical Significance (p-value) |

|---|---|---|

| Resting Membrane Potential | Depolarized | < 0.05 |

| After-Hyperpolarization (AHP) Amplitude | Significantly enhanced | < 0.01 |

| Action Potential Area | Significantly increased | < 0.001 |

| Action Potential Rise Time & Decay Time | Significantly increased | < 0.001 |

| Action Potential Duration (Half-width) | Significant broadening | < 0.001 |

| Neuronal Firing Frequency | Significant reduction | < 0.001 |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What are the most critical steps to prevent microbial contamination during the dissection of neural tissue?

The dissection phase is high-risk due to the exposure of tissue to non-sterile environments. The most critical steps include [9] [48]:

- Proper Sacrifice and Surface Sterilization: Ensure the sacrifice method (e.g., CO2 asphyxiation) is performed away from the dissection area. The skull should be briefly rinsed with 70% ethanol before opening to minimize the introduction of fur-borne contaminants.

- Meninges Removal: The meninges are a primary source of fibroblast and microbial contamination. They must be removed carefully and completely with fine forceps, taking care not to puncture the underlying brain structure [9] [28].

- Sterile Instrumentation: Use autoclaved instruments and consider using a fresh set of sterile tools for each animal or brain region to prevent cross-contamination [46].

Q2: How can I quickly identify the type of contamination affecting my neuronal cultures?

Early and accurate identification is key to managing contamination. The table below summarizes common contaminants and their characteristics [46] [48]:

Table 1: Identification of Common Cell Culture Contaminants

| Contaminant Type | Visible Culture Characteristics | Microscopic Indicators | Recommended Detection Methods |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bacteria | Rapid turbidity/yellowing of medium; sharp pH drop [46]. | "Black sand-like" particles moving erratically [46]. | Gram staining, culture methods [46]. |

| Fungi/Yeast | Visible filamentous structures or white spots; yellow precipitates [46]. | Fungal hyphae or budding yeast cells [46]. | Microscopy, culture on antifungal plates [46]. |

| Mycoplasma | Premature yellowing of medium; subtle growth slowdown; cell deterioration [46] [48]. | No visible change; may cause altered cell morphology [48]. | Fluorescence staining (Hoechst), PCR, ELISA [46] [48]. |

Q3: Are antibiotics a recommended long-term solution for preventing contamination in primary neuronal cultures?

No, the routine long-term use of antibiotics is not recommended. While they can be useful as a short-term prophylactic during the initial isolation phase, continuous use can mask low-level contaminations, promote the development of antibiotic-resistant strains, and has been shown to alter gene expression in cultured cells, potentially compromising experimental outcomes [48]. Strict aseptic technique is the only reliable long-term strategy [19] [48].

Troubleshooting Guide: Common Isolation and Culture Problems

Problem 1: Low Neuronal Viability After Dissociation

- Potential Cause #1: Over-digestion with proteolytic enzymes.

- Potential Cause #2: Excessive mechanical trituration.

- Potential Cause #3: Delay in processing.

- Solution: Keep all tissues and dissected structures on ice-cold buffers (e.g., HBSS) at all times. Limit the total dissection time to under one hour to maintain neuronal health [9].

Problem 2: High Glial Cell Contamination in Long-Term Cultures

- Potential Cause: Proliferation of astrocytes and microglia in serum-containing media.

- Solution: For CNS neurons (cortex, hippocampus, spinal cord), use a serum-free, defined medium such as Neurobasal medium supplemented with B-27 or CultureOne. This formulation supports neuronal growth while suppressing glial proliferation [9] [49]. For specific applications, the use of antimitotic agents like cytosine arabinoside (Ara-C) can be introduced transiently after neurons have adhered.

Problem 3: Inconsistent Results and High Batch-to-Batch Variability

- Potential Cause #1: Uncontrolled variables in animal source and dissection.

- Solution: Standardize the embryonic day (E) or postnatal day (P) of the animals used. For example, cortical neurons are typically isolated from E17-E18 rats, while hippocampal neurons can be from P1-P2 pups [9]. Train extensively on dissection to minimize technical variability.

- Potential Cause #2: Unverified reagents.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Aseptic Primary Neuron Culture

| Reagent/Material | Function | Example & Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Dissection Buffer | Maintains ionic balance and pH during tissue collection. | Ice-cold Hanks' Balanced Salt Solution (HBSS), with or without Ca2+/Mg2+ [9] [49]. |

| Enzymatic Dissociation Agent | Breaks down extracellular matrix to create single-cell suspension. | Trypsin-EDTA; concentration and time must be meticulously optimized for each tissue type [9] [49]. |

| Culture Medium | Provides nutrients and signaling molecules for cell survival and growth. | Neurobasal-type medium is standard. Use serum-free supplements like B-27 to suppress glial growth [9] [49]. |

| Substrate Coating | Provides a surface for neuronal adhesion and neurite outgrowth. | Poly-D-lysine (PDL) or Poly-L-ornithine, often followed by laminin, to coat culture vessels [9]. |

| Contamination Prevention | To prevent or treat microbial contamination. | Primocin is a broad-spectrum antibiotic designed for primary cells. Plasmocin is used specifically for mycoplasma elimination [51]. |

Experimental Workflow: Aseptic Primary Neuron Isolation

The following diagram visualizes the core procedural workflow for the aseptic isolation of primary neurons, integrating critical steps for contamination prevention.

Substrate Coating and Preparation Under Sterile Conditions

Maintaining sterile conditions during substrate coating and preparation is a critical foundation for successful long-term neuronal culture experiments. Contamination, whether chemical or biological, can compromise cellular health, alter phenotypic expression, and lead to irreproducible results, ultimately invalidating complex and time-consuming research [19] [6]. This guide outlines essential protocols and troubleshooting strategies to ensure the integrity of your neuronal cultures from the very first step: preparing the growth substrate.

The core principle is that sterility must be maintained throughout the entire workflow, from handling the coating reagents to the final preparation of the culture vessel. Adherence to aseptic technique is non-negotiable, as the nutrient-rich environment of cell culture media is an ideal breeding ground for microorganisms [2].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: Why is sterile technique during substrate coating so crucial for neuronal cultures? Neuronal cultures are often long-term experiments, sometimes maintained for weeks. Contamination introduced during the initial coating phase can remain cryptic (undetected) initially but proliferate over time, secreting toxins and altering the cellular microenvironment [52] [6]. This can lead to stunted neurite outgrowth, increased cell death, and unreliable data in drug development screens.

Q2: Can I use antibiotics in my coating solutions to prevent contamination? It is not recommended to routinely add antibiotics directly to coating solutions. The continuous use of antibiotics can mask poor aseptic technique and promote the development of antibiotic-resistant strains [5] [6]. Furthermore, some antibiotics can cross-react with cells and interfere with the cellular processes under investigation. Their use should be a last resort, not a standard practice [5].