A Comprehensive Guide to Preventing, Detecting, and Troubleshooting Cell Culture Contamination in Neuronal Studies

This article provides a systematic framework for researchers and drug development professionals to manage cell culture contamination in neuronal studies.

A Comprehensive Guide to Preventing, Detecting, and Troubleshooting Cell Culture Contamination in Neuronal Studies

Abstract

This article provides a systematic framework for researchers and drug development professionals to manage cell culture contamination in neuronal studies. It covers the foundational knowledge of common contaminants and their specific impacts on neuronal cells, explores advanced detection methodologies, offers step-by-step troubleshooting and decontamination protocols, and establishes best practices for validation and quality control. By addressing the unique vulnerabilities of primary neurons, stem cell-derived cultures, and immortalized lines, this guide aims to safeguard experimental integrity, ensure reproducible results in neuroscience research, and protect valuable neuronal models.

Understanding Contamination: Threats to Neuronal Culture Integrity and Data Validity

Contamination in neuronal cell culture is not merely an inconvenience; it is a catastrophic failure that compromises data integrity, misdirects research resources, and ultimately undermines the validity of scientific discoveries. The unique vulnerability of primary neurons, their limited lifespan, and the profound consequences of subtle physiological changes caused by contaminants like mycoplasma make prevention and detection a critical mandate for every neuroscience laboratory. This technical support center provides targeted troubleshooting guides and FAQs to help researchers safeguard their invaluable neuronal studies.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

What makes neuronal cell cultures particularly vulnerable to contamination? Primary neuronal cultures are exceptionally sensitive because they are non-proliferating, finite cell lines derived directly from nervous tissue. They cannot be passaged indefinitely and are highly susceptible to subtle changes in their environment. Contaminants like mycoplasma can alter cellular metabolism and cause chromosomal aberrations, effects that are particularly devastating in experiments measuring precise neuronal signaling, synaptic function, or inflammatory responses [1].

Beyond cloudiness, what are the subtle signs of contamination I might miss? While bacteria and fungi often cause turbidity, mycoplasma contamination is stealthier. Key indicators include a persistent, unexplained drop in pH (medium turns yellow), subtle changes in cell morphology, poor cell health despite fresh medium, and a failure of cells to thrive. These signs can be easily mistaken for other experimental problems, which is why routine, specific testing is essential [1] [2].

My lab uses antibiotics routinely. Is this sufficient for preventing contamination? No. Reliance on antibiotics is a dangerous practice. Chronic antibiotic use can promote the development of resistant bacterial strains, mask low-level contamination, and has been shown to alter gene expression in cultured cells, which could confound your research results. Antibiotics should not be used as a substitute for rigorous aseptic technique [1].

How can I distinguish between contaminated primary neurons and unhealthy cultures due to isolation stress? This is a critical diagnostic challenge. Contamination often affects the entire culture uniformly and persists across subsequent medium changes. Stress from isolation is typically most severe immediately after plating and improves over time with proper care. Definitive distinction requires targeted tests: PCR for mycoplasma, Gram staining for bacteria, or culturing aliquots of medium on nutrient agar. Always culture a sample of your medium alone as a negative control [3] [1].

What is the most critical step in reviving a frozen vial of neuronal cells to minimize contamination risk? The most critical step is the rapid and complete removal of the cryoprotectant (e.g., DMSO) after thawing. DMSO is toxic to cells at room temperature. Thaw the vial quickly, immediately dilute the cell suspension in pre-warmed culture medium, and centrifuge to pellet the cells. Discard the supernatant containing the DMSO and resuspend the pellet in fresh, complete medium before seeding. This process minimizes cellular stress and prevents the carryover of potential contaminants from the freeze medium [2].

Troubleshooting Guides

Guide 1: Identifying Contamination Type and Source

| Observation | Potential Contaminant | Confirmation Test | Common Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| Rapid medium turbidity, pH change (yellow) | Bacteria | Gram stain, culture medium on nutrient agar | Non-sterile reagents, poor aseptic technique [2] |

| Cloudy medium with floating filaments or spots | Fungi/Yeast | Microscopy (visible structures), culture on agar | Laboratory air, contaminated water bath [1] |

| No turbidity, but unexplained cell death, altered metabolism, or poor growth | Mycoplasma | PCR, DNA staining (Hoechst/DAPI), ELISA | Fetal bovine serum, lab personnel, cross-contamination from other cell lines [1] |

| Rounded, detached cells; viral cytopathic effect (varies) | Virus | PCR, plaque assay, electron microscopy | Original tissue isolate, contaminated reagents [1] |

Guide 2: Proactive Prevention Checklist for Neuronal Cultures

- Personal Protective Equipment (PPE): Always wear a lab coat, gloves, and, in some cases, a face mask to protect samples from human aerosol droplets [4].

- Biosafety Cabinet Management: Work within a certified biosafety cabinet with uninterrupted airflow. Wipe down all items with 70% ethanol before introduction. Keep the cabinet uncluttered and avoid rapid movements that disrupt the air barrier [1].

- Aseptic Technique: Use sterile, single-use pipettes. Avoid touching the tip of pipettes or the necks of bottles. Perform all operations quickly and carefully to minimize exposure to the environment [1].

- Reagent and Equipment Quality: Use laboratory-grade water for all solutions. Source media and sera from reputable suppliers that provide sterility and endotoxin testing certification. Decontaminate equipment regularly with appropriate agents (e.g., 70% ethanol, sodium hypochlorite) [1].

- Routine Monitoring and Authentication: Check cultures daily under a microscope. Regularly test cell lines for mycoplasma (e.g., quarterly) and authenticate cell lines to rule out cross-contamination [1].

Experimental Protocols for Contamination Management

Protocol 1: Routine Mycoplasma Detection via DNA Staining

Principle: This method uses a fluorescent DNA-binding dye (e.g., DAPI or Hoechst) to stain DNA. Mycoplasma, which adheres to the surface of host cells, appears as punctate or filamentous fluorescence in the extranuclear regions.

Materials:

- Cell culture to be tested (test cell line)

- Known mycoplasma-negative cells (negative control)

- Phosphate-Buffered Saline (PBS), sterile

- Fixative (e.g., Methanol or Acetic acid:MeOH 1:3)

- DNA stain (e.g., 1 µg/mL Hoechst 33258 in PBS)

- Mounting medium

- Fluorescence microscope

Method:

- Seed Cells: Seed the test and control cells onto sterile coverslips in a multi-well plate and culture until sub-confluent.

- Wash and Fix: Aspirate the medium and gently wash the monolayer with PBS. Add fixative to cover the cells and incubate for 15-30 minutes at room temperature. Aspirate the fixative and allow to air dry completely.

- Stain: Add enough DNA stain solution to cover the cells and incubate for 15-30 minutes in the dark.

- Rinse and Mount: Aspirate the stain and rinse gently with PBS. Mount the coverslip onto a microscope slide with mounting medium.

- Visualize: Examine under a fluorescence microscope with appropriate filters. The nucleus of mammalian cells will be brightly stained. A positive mycoplasma contamination is indicated by the presence of small, bright extranuclear spots or a fibrous pattern on the cell surface or in between cells [1].

Protocol 2: Establishing Sterile Sampling and Handling for Primary Isolation

Principle: This protocol outlines decontamination steps to prevent contamination during the collection and processing of primary brain tissue, which is a high-risk step.

Materials:

- DNA-free dissection tools (or decontaminated)

- Personal protective equipment (PPE): gloves, mask, clean lab coat

- 80% Ethanol

- DNA decontamination solution (e.g., fresh 1-2% sodium hypochlorite)

- Sterile PBS or dissection medium

Method:

- Decontaminate Tools: Clean all dissection tools thoroughly. Ideally, use single-use, DNA-free tools. For re-usable tools, decontaminate with 80% ethanol (to kill organisms) followed by a nucleic acid degrading solution like sodium hypochlorite (to remove residual DNA). Rinse with sterile water and dry before use [4].

- Wear Appropriate PPE: Cover exposed body parts to limit sample contact with skin and aerosols from breathing [4].

- Dissection: Perform the brain dissection and meninges removal as quickly as possible in a sterile environment to minimize exposure [3].

- Tissue Processing: All subsequent steps—mechanical disruption, enzymatic digestion (e.g., with trypsin), and filtration—should be performed using sterile techniques and reagents in a biosafety cabinet [3].

- Include Controls: Process a sample of the dissection medium alone as a negative control to monitor for introduced contaminants during the procedure [4].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

| Item | Function in Neuronal Research |

|---|---|

| DMSO (Dimethyl Sulfoxide) | A common cryoprotective agent used to preserve cells during freezing by preventing ice crystal formation. Must be removed after thawing [2]. |

| Accutase/Accumax | Milder enzymatic cell detachment agents used for passaging sensitive adherent cells. They are less toxic than trypsin and better preserve cell surface proteins for downstream analysis like flow cytometry [5]. |

| CD11b (ITGAM) Microbeads | Antibody-conjugated magnetic beads for the immunocapture of microglial cells from a mixed primary brain cell suspension [3]. |

| ACSA-2 Microbeads | Antibody-conjugated magnetic beads for the subsequent immunocapture of astrocytes from a cell suspension [3]. |

| Percoll Gradient | A density-based centrifugation medium used to isolate specific cell types (e.g., microglia, astrocytes) from a dissociated brain tissue homogenate without expensive antibodies or enzymes [3]. |

| Phenol Red | A pH indicator in cell culture media. A color change from red to yellow indicates acidification, a sign of high metabolic activity from cell overgrowth or microbial contamination [2]. |

| Hoechst 33258 / DAPI | Fluorescent DNA-binding dyes used to stain cellular DNA, crucial for detecting mycoplasma contamination that appears as extranuclear staining [1]. |

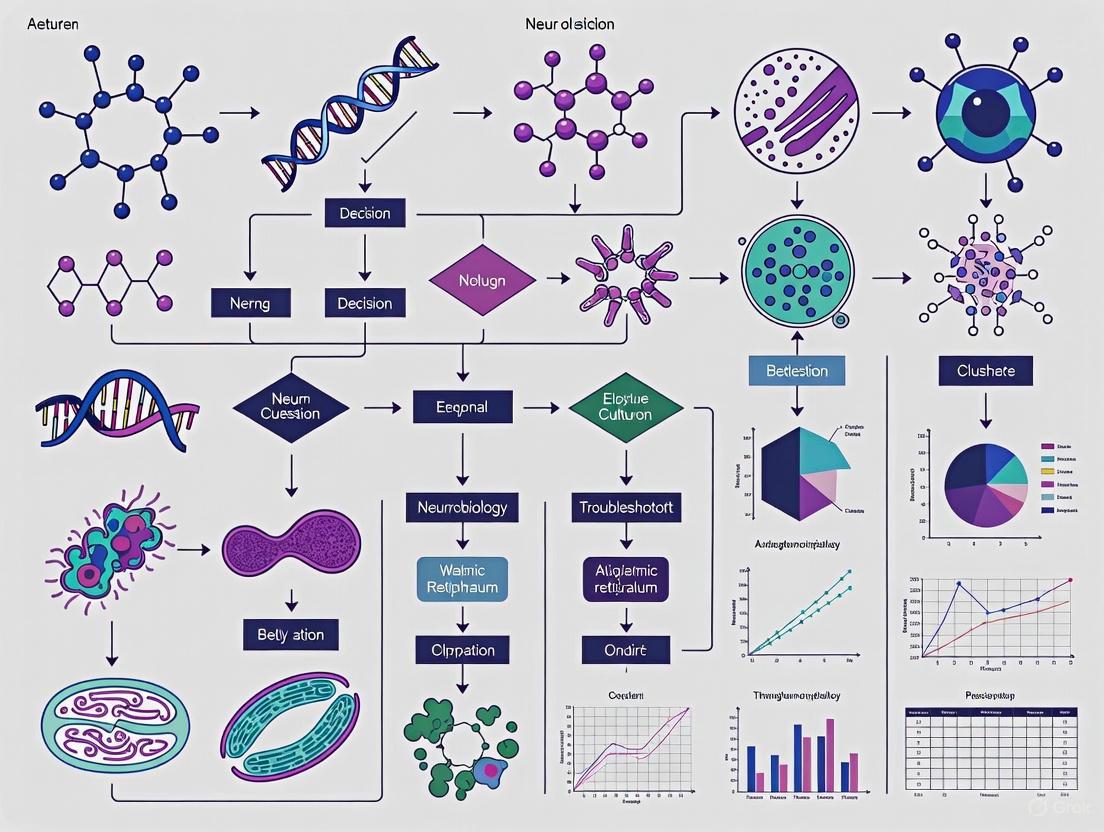

Experimental Workflow and Pathway Diagrams

Contamination Detection Pathway

Primary Neuron Isolation & Contamination Control

FAQ: Biological Contaminants in the Cell Culture Lab

What are the most common types of biological contaminants? Biological contaminants in cell culture are typically classified into broad categories: bacteria, fungi (which includes molds), and yeast [6]. Viruses, mycoplasma, and protozoa are also significant threats but are often harder to detect [5] [6].

How can I tell if my neuronal cell culture is contaminated? Visual inspection under a microscope is the first line of defense. Bacteria often appear as small, shimmering granules between cells and can cause the culture medium to become cloudy [7] [6]. Fungi form thin, filamentous structures called hyphae (mycelium) that can develop into fuzzy, cotton-like masses, sometimes with colored spores [7]. Yeast cells are oval or round and typically bud to form smaller daughter cells, appearing as small, separate colonies [7] [8].

My culture isn't cloudy, but the cells are dying. Could it still be contamination? Yes. Certain contaminants, like mycoplasma, do not cause visible cloudiness but can persist covertly, altering cell metabolism and growth and leading to unreliable experimental results [5] [6]. Mycoplasma is one of the most common and insidious contaminants in cell culture.

What is cross-contamination? Cross-contamination occurs when one cell line is overgrown by another, more robust cell line (e.g., HeLa cells). This is a form of biological contamination that can lead to invalid and irreproducible research data [5] [6]. It is crucial to obtain cell lines from reputable banks and perform periodic authentication [6].

Troubleshooting Guide: Identification and Analysis

Accurate identification is the first step in troubleshooting. The table below summarizes the characteristic signs of common contaminants.

Table 1: Identifying Common Biological Contaminants in Cell Culture

| Contaminant Type | Typical Signs of Presence | Common Examples | Potential Impact on Neuronal Cultures |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bacteria | Cloudy culture medium; fine, shimmering granules under phase-contrast microscopy; rapid pH change (yellow) [7] [6]. | Salmonella, Listeria, E. coli, Pseudomonas [9] [10]. | Nutrient depletion, altered pH, neurotoxic byproducts, rapid culture death. |

| Fungi / Mold | Fuzzy, cotton-like, or thread-like structures that grow over time; may produce pigmented spores (e.g., green, black) [7]. | Penicillium, Aspergillus [7]. | Overgrowth of culture, nutrient competition, possible mycotoxin production. |

| Yeast | Small, round or oval particles that bud off smaller particles; often appear as discrete colonies [7] [8]. | Candida spp., Saccharomyces cerevisiae [11] [8]. | Competition for nutrients, acidification of medium, potential to bud and spread rapidly. |

| Mycoplasma | No visible cloudiness; covert persistence often indicated by poor cell growth, abnormal morphology, or positive test results [5]. | M. pneumoniae, M. orale, M. hyorhinis [5]. | Altered gene expression, metabolism, and membrane integrity; unreliable neuronal signaling data. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Reagents for Contamination Control

Table 2: Essential Reagents for Managing Biological Contaminants

| Reagent / Material | Function | Example Application in Neuronal Culture |

|---|---|---|

| Antibiotics | Inhibit or kill bacterial contaminants. | Used prophylactically in some media (e.g., Penicillin-Streptomycin) but can mask low-level infections [5] [7]. |

| Antimycotics | Inhibit the growth of fungal and yeast contaminants. | Amphotericin B or PPM can be added to media to prevent fungal overgrowth, especially in primary culture setups [7]. |

| PPM (Plant Preservative Mixture) | A broad-spectrum biocide effective against bacteria, fungi, and yeast [7]. | Heat-stable additive for culture media to prevent contamination from explants or during manipulation [7]. |

| Chromogenic Culture Media | Selective media that produce colored colonies for specific pathogens, allowing for rapid identification [10]. | Used diagnostically to identify specific bacterial contaminants (e.g., S. aureus, E. coli) from a contaminated culture [10]. |

| Mycoplasma Detection Kit | Specifically detects mycoplasma contamination via PCR, ELISA, or luciferase-based assays. | Essential for routine monthly screening of precious neuronal stock cultures to ensure data validity [5]. |

| DNA Profiling Kits | Authenticates cell lines via STR (Short Tandem Repeat) profiling. | Critical for confirming the identity of neuronal cell lines and ruling out cross-contamination [5]. |

Experimental Protocol: Systematic Workflow for Contamination Identification

The following diagram provides a logical workflow for diagnosing and responding to suspected contamination in your neuronal cultures.

FAQs: Understanding Contamination in Neural Cell Cultures

1. What are the most common signs that my neural cell culture is contaminated with mycoplasma?

Mycoplasma contamination is often called "silent" because it typically does not cause cloudiness in the culture medium. Common signs under the microscope include unexplained changes in cell growth rate or morphology, reduced transfection efficiency, and the presence of tiny black dots on the cells. For neuronal cultures specifically, you might observe impaired neurite outgrowth or aberrant synaptic activity, which can be mistaken for experimental treatment effects. These contaminants can affect virtually all aspects of cell physiology, including chromatin organization, gene expression, and metabolic pathways, ultimately compromising your experimental data [12] [13] [14].

2. Why are primary neural cultures particularly vulnerable to contamination?

Primary neurons and glial cells isolated from brain tissue are highly sensitive and have limited proliferative capacity. The isolation process itself, which involves multiple steps of dissection, enzymatic digestion, and mechanical trituration, represents a significant contamination risk. Furthermore, these primary cells require specific, nutrient-rich media and specialized substrate coatings, creating an ideal environment for microbial growth if contaminants are introduced. Unlike immortalized cell lines, primary neural cells cannot be easily "recovered" with antibiotics and are often sacrificed once contaminated, leading to significant losses of time and valuable tissue [3] [15].

3. What is the most reliable method to detect mycoplasma in my cultures?

While several methods exist, PCR-based detection is widely considered the most sensitive, specific, and rapid technique. It can identify over 60 species of Mycoplasma, Acholeplasma, Spiroplasma, and Ureaplasma, including the top eight species that account for 95% of cell culture contamination. This method can provide results within hours, allowing for a quick response. Other methods include direct culture (the gold standard but requiring 4-5 weeks) and indirect DNA staining with Hoechst 33258, which reveals characteristic filamentous patterns in the cytoplasm of infected cells [12] [13].

4. Can viral contamination be detected visually, and what are its impacts on neural research?

Viral contamination is notoriously difficult to detect visually, as it often does not cause obvious changes in medium clarity. However, some viruses may induce cytopathic effects (CPE), observable under a microscope as cell rounding, syncytia formation (cell fusion), or lysis. The impact on neural research is profound; viral contaminants can alter host cell immune responses, dysregulate hundreds of host genes, and integrate into the cellular genome. This can lead to misinterpretation of gene expression studies, such as RNA-seq or ATAC-seq data, where viral sequences can align to the host genome and create false positives [13] [16].

5. What are the most critical steps to prevent contamination when working with primary brain cells?

Prevention is the most cost-effective strategy. Key steps include:

- Strict Aseptic Technique: Always work in a certified biosafety cabinet, disinfect all surfaces and items with 70% ethanol, and avoid simultaneous handling of multiple cell lines.

- Reagent Quality Control: Use only certified, mycoplasma-free reagents, sera, and cell lines. Aliquot media and supplements to minimize repeated exposure.

- Quarantine and Testing: Isolate all new cell lines until they are confirmed to be contamination-free through rigorous testing.

- Environmental Control: Maintain clean incubators, change water pans regularly, and avoid creating aerosols that can disperse contaminants [12] [13] [14].

Troubleshooting Guides

Guide 1: Identifying Common Contaminants in Neural Cultures

The table below summarizes the key characteristics of major contamination types to aid in visual identification.

Table 1: Common Contamination Profiles in Cell Culture

| Contaminant Type | Visual Signs in Medium | Microscopic Appearance | Impact on Neural Cells |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mycoplasma | No cloudiness or color change [17] [14] | Tiny black dots; slow cell growth; abnormal cell morphology [17] | Chromosomal aberrations; changes in gene expression; disruption of neurotransmission [12] [13] |

| Bacteria | Turbid/yellowish; possible sour odor [14] | Small, motile particles (1-5 µm); "quicksand" movement [14] | Rapid pH shift; nutrient depletion; cell death [14] |

| Yeast | Clear initially, becomes yellow/turbid over time [17] | Round or oval budding cells [17] | Competes for nutrients; can acidify medium [17] |

| Mold | Cloudy or fuzzy appearance [17] | Thin, thread-like filamentous hyphae [17] | Forms dense, fuzzy colonies that overwhelm the culture [17] |

| Virus | Typically no change [14] [16] | May show cytopathic effects (cell rounding, syncytia) or no change [16] | Alters immune signaling & gene expression; compromises genomic & transcriptomic data [13] [16] |

Guide 2: Mycoplasma Prevention and Detection Workflow

This workflow outlines a standard operating procedure for maintaining mycoplasma-free neural cultures.

Detailed Protocol for PCR-Based Mycoplasma Detection [13]:

Principle: This protocol uses universal PCR primers targeted to the 16S rRNA gene to detect over 60 species of Mycoplasma, Acholeplasma, Spiroplasma, and Ureaplasma.

Reagents:

- PCR primers:

- Mycoplasma-F: GGGAGCAAACAGGATTAGTATCCCT

- Mycoplasma-R: TGCACCATCTGTCACTCTGTTAACCTC

- 2× Taq Plus Master Mix

- TAE buffer (40 mM Tris-Acetate, 1 mM EDTA, pH 8.3)

- Cell culture supernatant

Procedure:

- Sample Preparation: Culture cells for at least 12 hours. Transfer 200 µL of cell culture supernatant into a sterile 1.5 mL tube.

- Heat Inactivation: Incubate the sample at 95°C for 5 minutes to inactivate nucleases. The sample can be stored at -20°C at this point.

- PCR Setup: Prepare a PCR master mix on ice. For each reaction, combine:

- 12.5 µL of 2× Taq Plus Master Mix

- 1 µL of each forward and reverse primer (10 µM)

- 8.5 µL of Nuclease-Free Water

- 2 µL of the prepared template DNA (supernatant)

- PCR Amplification: Run the PCR using the following cycling conditions:

- Initial Denaturation: 95°C for 5 min

- 35 Cycles:

- Denaturation: 95°C for 30 sec

- Annealing: 60°C for 30 sec

- Extension: 72°C for 1 min

- Final Extension: 72°C for 5 min

- Analysis: Analyze the PCR products by running them on a 1.5% agarose-TAE gel containing 1× Gel stain. A positive result will show a band of the expected size (approximately 500 bp).

Guide 3: Decision Matrix for a Contaminated Neural Culture

Discovering contamination requires immediate and decisive action. Follow the logic below to determine the appropriate response.

Eradication Protocol for Mycoplasma (If Attempted) [13] [18]: If a culture is deemed worth saving, commercial mycoplasma removal agents (e.g., P-CMR-001) can be used. Treatment typically lasts 12-21 days. A clear effect is often observed after 3 days, but treatment should continue, and the culture must be retested with a mycoplasma detection kit to confirm complete eradication before returning to general use.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents for Contamination Control

Table 2: Key Research Reagents for Prevention, Detection, and Eradication

| Reagent / Kit | Primary Function | Brief Description & Application |

|---|---|---|

| Mycoplasma Detection PCR Kit [13] [17] | Detection | Contains primers targeting 16S rRNA genes for sensitive and specific identification of mycoplasma species via PCR. |

| Mycoplasma Removal Agent [17] [18] | Eradication | A specialized reagent (e.g., P-CMR-001) added to culture medium to eliminate mycoplasma over a 2-3 week treatment course. |

| Hoechst 33258 Stain [12] | Detection | A fluorescent DNA-binding dye used in indirect staining methods to visualize mycoplasma DNA in the cytoplasm of infected cells. |

| Antibiotic-Antimycotic (P/S) | Prevention | A mixture of Penicillin and Streptomycin used to prevent bacterial and fungal growth in non-critical applications. Note: Ineffective against mycoplasma. [12] |

| Zell Shield [13] | Prevention | A broad-spectrum reagent effective against mycoplasma, bacteria, and fungi, often used as an alternative to standard antibiotics. |

| MycoStrip [13] | Detection | A rapid, dipstick-style test for detecting mycoplasma contamination in cell culture samples. |

This technical support center provides targeted guidance for researchers troubleshooting contamination in neuronal cell culture studies. Endotoxins, or lipopolysaccharides (LPS), are pervasive contaminants derived from the outer membrane of Gram-negative bacteria. In neuronal research, their potent bioactivity can trigger neuroinflammatory and neurotoxic effects, potentially compromising experimental outcomes and leading to misleading conclusions [19] [20]. This resource offers practical, evidence-based protocols to identify, quantify, and mitigate these risks.

FAQ: Endotoxin Contamination in Neuronal Research

What are endotoxins and why are they a particular concern for neuronal studies?

Endotoxins are complex lipopolysaccharides (LPS) found in the outer membrane of Gram-negative bacteria. They are ubiquitous, thermostable contaminants that can persist in the environment and reagents even in the absence of live bacteria [19]. In neuronal studies, they are a critical concern because they can induce potent neuroinflammatory and neurotoxic responses. Endotoxin activates the Toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4) signaling pathway on innate immune cells in the brain, such as microglia, leading to the release of pro-inflammatory cytokines (e.g., IL-1β, IL-6, TNF-α) [19] [20]. This inflammation can lead to secondary neurotoxicity, synaptic loss, and impaired neuronal function, which can confound the results of studies investigating primary neurotoxicants or therapeutic agents [20].

How can I determine if my neuronal cell culture is contaminated with endotoxin?

Direct observation of bacterial contamination (e.g., turbid media) may not be present with endotoxin, as the contaminant can be the LPS molecule itself without viable bacteria [21]. Specialized detection assays are required. The gold-standard method is the Limulus Amebocyte Lysate (LAL) assay, which is derived from horseshoe crab blood and comes in gel-clot, turbidimetric, and chromogenic formats [19]. Modern recombinant alternatives (rFC and rCR assays) are now recognized by regulatory bodies like the USP and offer a sustainable, animal-free method with high specificity and reduced batch-to-batch variability [22] [23]. It is crucial to validate that your nanomaterials or culture reagents do not interfere with the chosen assay's readout [19].

My reagents are sterile. How can they still be contaminated with endotoxin?

Sterility and the absence of endotoxin are not the same. Endotoxin is remarkably heat-stable and can survive standard autoclaving and many sterilization routines [19] [20]. It can be introduced through various sources, including:

- Water and raw materials used in culture media and buffers.

- Serum and other biological additives.

- Chemicals used to synthesize nanoparticles or other test compounds.

- Laboratory glassware and utensils that have not been properly depyrogenated (e.g., via dry-heat incineration at >250°C) [19].

What are the best practices for preventing endotoxin contamination in my experiments?

Prevention is the most effective strategy. Key practices include:

- Source Control: Use high-quality, endotoxin-tested reagents, water (WFI - Water for Injection), and serum.

- Aseptic Technique: Work in a laminar flow biosafety cabinet using strict sterile techniques.

- Depyrogenation: Use certified endotoxin-free plasticware. Depyrogenate glassware and tools by baking at 250°C for 30 minutes or 180°C for 3 hours [19].

- Synthesis in Clean Conditions: When producing nanomaterials, synthesize them under endotoxin-free conditions whenever possible, as depyrogenation post-synthesis can alter their physicochemical properties [19].

Troubleshooting Guides

Guide 1: Detecting and Quantifying Endotoxin in Nanomaterials and Reagents

Nanomaterials can often interfere with standard endotoxin detection assays, making accurate quantification challenging [19]. This protocol outlines a robust approach.

Materials:

- LAL reagent (chromogenic kinetic or gel-clot) or recombinant Factor C (rFC) assay kit [22] [23]

- Endotoxin-free water and consumables

- Control Standard Endotoxin (CSE)

- Heat block or water bath

- Microplate reader (for chromogenic/rFC assays)

Methodology:

- Sample Preparation: Prepare your nanomaterial or reagent suspension in endotoxin-free water. Create a series of dilutions to overcome potential interference.

- Interference Testing (Spike Recovery): This is a critical control.

- Split a sample into two aliquots.

- Spike one aliquot with a known amount of CSE (e.g., 0.1 EU/mL).

- Run the LAL or rFC assay on both the spiked and unspiked samples.

- Calculate % recovery = (Measured Endotoxin in Spiked Sample - Measured Endotoxin in Unspiked Sample) / Known Spike Concentration × 100.

- Acceptance Criterion: Recovery should be between 50% and 200% [23]. If outside this range, the sample is interfering, and further dilution or sample treatment is needed.

- Assay Execution: Perform the LAL or rFC assay according to the manufacturer's instructions. Always include a standard curve with CSE.

- Interpretation: Calculate the endotoxin concentration in your sample based on the standard curve and your dilution factor. Report in Endotoxin Units per milliliter (EU/mL) or per milligram (EU/mg) of nanomaterial.

Guide 2: Assessing Endotoxin-Induced Neurotoxicity in Vitro

This protocol uses high-content imaging to evaluate multiple facets of neuronal health, which is highly sensitive to inflammatory and toxic insults.

Materials:

- Human iPSC-derived neurons or primary neuronal cultures [24] [25]

- Cell culture plates (96- or 384-well, suitable for imaging)

- Purified endotoxin (LPS)

- Fixative (e.g., 4% PFA) and permeabilization buffer

- Antibodies: β-III-tubulin (neuronal marker), MAP2 (dendritic marker), Synapsin (synaptic marker)

- Nuclear stain (Hoechst or DAPI)

- Viability dye (e.g., Calcein AM) [24]

- ImageXpress Micro Confocal or similar high-content imaging system

- Analysis software (e.g., MetaXpress with Neurite Outgrowth Application Module) [24]

Methodology:

- Cell Treatment: Plate neurons and allow them to form mature networks (e.g., 14-21 days in vitro, DIV). Challenge the networks with a range of endotoxin concentrations for 24-72 hours.

- Endpoint Staining:

- Live-Cell Assay: Stain with Calcein AM (viability) and Hoechst (nuclei) to monitor real-time toxicity [24].

- Fixed-Cell Assay: Fix and immunostain for β-III-tubulin to visualize the entire neuronal network and a synaptic marker like synapsin.

- High-Content Imaging: Acquire images using a confocal high-content imager. Capture multiple fields and z-stacks per well for robust quantification.

- Image Analysis:

- Use the Neurite Outgrowth Application Module to quantify key parameters:

- Total Neurite Outgrowth: Sum of the area of all neurites.

- Average Neurite Length: Mean length of neurites per neuron.

- Branching Points: Number of branches per neuron.

- Use the Cell Scoring Application Module to:

- Count the total number of neurons.

- Quantify synaptic puncta density.

- Use the Neurite Outgrowth Application Module to quantify key parameters:

- Interpretation: A significant, dose-dependent reduction in neurite outgrowth, synaptic density, or cell viability indicates endotoxin-induced neurotoxicity. Compare the IC50 values for different endpoints to understand the compound's potency [24].

Data Presentation

Table 1: Endotoxin Limits and Detection Methods

| Product Type | Regulatory Limit (EU/mL) | Recommended Test Method | Key Advantages |

|---|---|---|---|

| Injectable Drugs / Medical Devices | 0.2 (for intrathecal) | LAL (Kinetic Chromogenic) [20] | FDA-approved, extensive historical data |

| 5.0 (general) [20] | Recombinant Factor C (rFC) [22] | Animal-free, superior batch consistency, specific for endotoxin | |

| Cell Culture Media / Reagents | Not regulated, but <0.1 is recommended for sensitive cells | rFC or LAL | Prevents immune activation in vitro |

| Engineered Nanomaterials | Not regulated; aim for <1.0 EU/mg for in vivo studies [19] | rFC with interference testing [19] | Reduced interference from nanomaterials |

Table 2: Key Reagents for Endotoxin and Neurotoxicity Research

| Reagent / Kit | Function / Application | Key Feature |

|---|---|---|

| Recombinant Factor C (rFC) Assay | Detects bacterial endotoxin without LAL [22] [23] | Sustainable, animal-free, high specificity |

| LAL Assay Kit | Traditional endotoxin detection [19] | Compendial method, widely accepted |

| iPSC-derived Human Neurons | Biologically relevant model for neurotoxicity screening [24] [25] | Human phenotype, available in large quantities |

| Neurite Outgrowth SW Module | Automated quantification of neurite parameters from images [24] | High-content, multiplexed data (length, branches, etc.) |

| Mitochondrial Dyes (e.g., JC-10, TMRM) | Assess mitochondrial health and membrane potential [24] [25] | Early indicator of cellular stress and toxicity |

Experimental Visualization

Diagram 1: Endotoxin-Induced Neuroinflammatory Signaling

The following diagram illustrates the TLR4-mediated signaling pathway activated by endotoxin, leading to neuroinflammation and potential neurotoxicity.

Diagram 2: Neurotoxicity Screening Workflow

This flowchart outlines a high-content screening workflow for assessing endotoxin-induced neurotoxicity in cultured neurons.

Cell culture contamination represents a significant threat to the integrity of biomedical research, particularly in the sensitive field of neuronal studies. Undetected contaminants can profoundly alter neuronal physiology, metabolism, and gene expression, leading to irreproducible results and erroneous scientific conclusions [26]. This technical support center provides a comprehensive troubleshooting guide for researchers navigating the challenges of contamination in neuronal cell cultures. The content is framed within a broader thesis on troubleshooting cell culture contamination, offering specific methodologies, detection protocols, and mitigation strategies to safeguard the validity of neuronal research and drug development applications.

FAQs: Addressing Critical Concerns in Neuronal Cell Culture

Q1: Our neuronal cultures show no obvious turbidity, but we observe slowed neurite outgrowth and premature cell death. What could be the cause?

This is a classic sign of mycoplasma contamination, which is often cryptic but exerts profound effects on neuronal health [21] [17]. Mycoplasma parasitizes cell culture media, competing for essential nutrients and altering the cellular environment [21]. This nutrient deprivation can impair neuronal metabolism, leading to the observed phenotypic changes. Diagnosis requires specific methods such as fluorescence staining with DNA-binding dyes like Hoechst 33258, PCR-based mycoplasma detection kits, or electron microscopy [21] [27].

Q2: We've detected bacterial contamination in a precious primary neuronal culture. Is it possible to rescue the cells?

The decision to rescue a contaminated culture is a trade-off between the value of the cells and the risk of unreliable data [27]. For primary neuronal cultures, which are often irreplaceable, a rescue attempt may be justified.

- Procedure: Immediately isolate the contaminated culture. Wash the cells gently with PBS containing high concentrations of antibiotics (e.g., penicillin-streptomycin or gentamicin) [21]. Replace with fresh, antibiotic-supplemented medium. Treatment should continue for at least 3-5 days, with daily monitoring. After the contamination appears cleared, culture the cells for several passages without antibiotics to ensure it is truly eliminated [28].

- Critical Consideration: Be aware that antibiotics can themselves induce changes in cell gene expression and physiology [27]. All experimental data generated from rescued cultures should be interpreted with caution, and validation in a clean culture is strongly recommended.

Q3: What are the most likely sources of contamination if we consistently practice aseptic technique but still encounter issues?

Even with good technique, contamination can arise from:

- Laboratory Equipment: Shared incubators and water baths are common hotspots [27]. Incubators should be cleaned monthly with Lysol and 70% ethanol, and water trays should be cleaned often with autoclaved, distilled water [27].

- Raw Materials: Contaminated media, serum, or reagents [27]. While suppliers perform sterility testing, the probability of a contaminant is never zero. For sensitive neuronal cultures, consider filter-sterilizing media prior to use.

- The Researchers Themselves: Humans are the most frequent source of contamination [28]. Avoid talking, coughing, or sneezing near cultures, bind long hair, and do not touch your face during cell handling [28].

Troubleshooting Guide: Identifying and Resolving Contamination

Common Microbial Contaminants and Their Signatures

Table 1: Characteristics of Common Cell Culture Contaminants

| Contaminant Type | Visual Culture Signs | Microscopic Signs (Neuronal Impact) | Recommended Detection Methods |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bacteria | Media turbidity; rapid yellow color shift (pH drop) [21] [17]. | Black sand-like particles in background; "quicksand" movement [21] [17]. Altered cell morphology, apoptosis [21]. | Direct observation, Gram staining, culture methods [21]. |

| Mycoplasma | No visible turbidity; premature medium yellowing; slowed cell growth [21] [17]. | Small black dots; abnormal neuronal morphology; stunted neurite outgrowth [21] [17]. | PCR, fluorescence staining (Hoechst), immunofluorescence [21] [27]. |

| Yeast | Media initially clear, turns yellow over time; possible white spots [21] [17]. | Round or oval budding particles [17]. Slowed cell growth, death [21]. | Direct observation, culture on antifungal plates, PCR [21]. |

| Mold | Fuzzy, filamentous structures on media surface [21] [17]. | Thin, thread-like hyphae [17]. | Direct observation, culture on antifungal plates [21]. |

Impact of Contaminants on Neuronal Function

Contaminants disrupt neuronal homeostasis through multiple interconnected pathways. The following diagram synthesizes how bacterial, mycoplasma, and fungal contaminants alter key neuronal functions, from physiology to gene expression.

Advanced Detection and Monitoring Protocols

Protocol: Mycoplasma Detection via Fluorescence Staining

Mycoplasma contamination is a pervasive problem that can drastically alter neuronal gene expression and function without causing media turbidity [21] [17]. This protocol uses a DNA-binding dye to visualize mycoplasma DNA adherent to the cell surface.

- Principle: Hoechst 33258 dye binds preferentially to DNA, staining both the host cell nucleus and any mycoplasma DNA attached to the cell's exterior [21] [27].

- Materials: Hoechst 33258 stain, positive control (known infected cells), negative control (mycoplasma-free cells), fixative (e.g., 3:1 methanol:acetic acid), fluorescence microscope [21].

- Procedure:

- Culture cells on a sterile glass coverslip until ~50% confluent.

- Rinse cells gently with PBS to remove serum, which can quench fluorescence.

- Fix cells with fixative for 10-15 minutes at room temperature.

- Rinse again with PBS to remove residual fixative.

- Stain with Hoechst 33258 (e.g., 0.5-1.0 µg/mL in PBS) for 15-30 minutes in the dark.

- Rinse with PBS to remove unbound dye.

- Mount the coverslip on a slide and visualize under a fluorescence microscope with a DAPI filter set.

- Interpretation: Mycoplasma-free cells will show only the bright, condensed nuclear DNA. Mycoplasma-contaminated cells will display a characteristic "halo" or speckled pattern of fluorescence in the cytoplasm, representing mycoplasma particles attached to the cell membrane [21].

Protocol: Routine Sterility Testing for Raw Materials

Ensuring the sterility of all culture components is critical for maintaining healthy neuronal cultures.

- Principle: A small sample of the material (e.g., media, serum, supplements) is inoculated into a nutrient broth and monitored for microbial growth [27].

- Materials: Trypticase soy broth or other general nutrient broth, sterile culture tubes, 37°C incubator.

- Procedure:

- Aseptically add 1-2 mL of the test material into 10 mL of sterile broth.

- Incubate the tube at 37°C for at least 14 days [27].

- Observe daily for signs of turbidity, which indicates microbial growth and contamination of the test material.

- Note: While this method is reliable, the 14-day incubation period can be a bottleneck. Newer methods, such as machine learning-aided UV absorbance spectroscopy, can provide results in under 30 minutes and are being developed for rapid sterility testing in cell therapy products [29].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Reagents for Contamination Management

Table 2: Essential Reagents for Contamination Prevention and Detection

| Reagent / Kit | Primary Function | Application Note |

|---|---|---|

| Penicillin-Streptomycin | Antibiotic mixture to prevent and treat bacterial contamination [21]. | Use as a short-term rescue agent; continuous use can mask contamination and affect gene expression [27] [28]. |

| Amphotericin B | Antifungal agent to treat yeast and mold contamination [21]. | Can be cytotoxic; use with caution for rescue operations only [17]. |

| Hoechst 33258 Stain | Fluorescent DNA dye for mycoplasma detection [21] [27]. | Requires fluorescence microscopy. A positive control is essential for result interpretation. |

| PCR-based Mycoplasma Detection Kit | Molecular method to detect mycoplasma-specific DNA sequences [21] [28]. | Highly sensitive and specific. Ideal for routine screening of master cell banks and valuable cultures. |

| Copper Sulfate | Additive for incubator water pans to inhibit fungal growth [17]. | A preventive measure to reduce contamination risk from the humidified incubator environment. |

| Mycoplasma Removal Agent | Reagent designed to eliminate mycoplasma from contaminated cultures [17]. | A specialized treatment for rescuing high-value cells; follow-up testing is mandatory. |

Best Practices for Preventing Contamination in Neuronal Cultures

Preventing contamination is always more effective than treating it. The following workflow outlines a comprehensive strategy, from initial cell handling to long-term storage, to minimize the risk of contamination in neuronal studies.

Implementing these structured protocols and vigilance plans is essential for producing reliable and reproducible data in neuronal cell culture research. Consistent adherence to detection and prevention strategies will safeguard your cultures from the profound and often cryptic impacts of contamination.

Proactive Defense and Advanced Detection Methods for Healthy Neuronal Cultures

In neuronal studies research, where cell cultures are invaluable and often irreplaceable, contamination can derail critical experiments, resulting in the loss of months of work. Aseptic technique within the biosafety cabinet (BSC) is not merely a best practice; it is the fundamental barrier protecting your research from microbial invasion. This guide provides targeted troubleshooting and FAQs to help you master this first line of defense, ensuring the integrity of your neuronal cultures.

Understanding Your Primary Tool: The Biosafety Cabinet

A Biosafety Cabinet is a ventilated enclosure that provides a sterile work area by directing HEPA-filtered air to protect the user, the cell culture, and the environment from particulate matter and aerosols [30]. Using the correct type of BSC is critical for successful cell culture.

Types of Biosafety Cabinets and Their Uses

The table below summarizes the common classes of BSCs and their appropriate applications [31]:

| Cabinet Class | Personnel Protection | Product Protection | Environmental Protection | Use Case in Neuronal Research |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Class I | Yes | No | Yes | Not suitable for sterile cell culture; may be used for enclosing equipment like tissue homogenizers. |

| Class II | Yes | Yes | Yes | The standard for most neuronal cell culture work. Provides an aseptic environment for handling cultures, transfections, and other sensitive procedures. |

| Class III | Yes | Yes | Yes | Used for high-risk pathogens (BSL-4); typically not required for standard neuronal cultures. |

Critical Note: Horizontal laminar flow "clean benches" are not BSCs. They discharge HEPA-filtered air toward the user, protecting the product but exposing the user to any aerosols created, and must never be used for handling cell culture materials or other potentially hazardous agents [31].

The Workflow for Aseptic Technique in a BSC

The following diagram outlines the logical sequence of actions required to establish and maintain an aseptic field before, during, and after work in a Biosafety Cabinet.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagent Solutions

Maintaining asepsis relies on more than just technique; it requires the correct use of sterilizing reagents and materials.

| Reagent/Material | Function | Key Consideration |

|---|---|---|

| 70% Ethanol | Primary disinfectant for gloves, work surfaces, and all items entering the BSC [32] [33]. | The water content increases efficacy by aiding in protein denaturation [33]. |

| HEPA Filter | High-Efficiency Particulate Air filter; removes 99.97% of particles ≥0.3 µm, ensuring sterile airflow [34]. | Integrity must be certified regularly. |

| Sterile Pipettes (Plastic/Glass) | For manipulating all liquids; prevent cross-contamination [32]. | Use each sterile pipette only once [32]. |

| Personal Protective Equipment (PPE) | Lab coat and gloves form a barrier between the user and the culture [32] [33]. | Gloves should be sprayed with 70% ethanol frequently during work [33]. |

| Pre-sterilized Reagents & Media | Provides a sterile foundation for cell culture work [33]. | Aliquot to prevent contamination of entire stock [33]. |

Troubleshooting Common Contamination Issues

This section addresses specific problems you might encounter, with guided solutions to correct them.

Problem: Cloudy culture media or unexplained pH shifts in neuronal cultures. Possible Cause & Solution:

- Bacterial Contamination: Check under a microscope for motile bacteria. Discard culture and media. Review your aseptic technique, ensure you are not pouring from media bottles, and confirm all reagents were sterile [32] [33].

- Mycoplasma Contamination: This is a common and often invisible contaminant. Test your cultures regularly using a PCR-based or other mycoplasma detection method [33].

Problem: Fungal growth (visible mycelia) in cultures. Possible Cause & Solution:

- Spores in the environment. Decontaminate incubators and water baths thoroughly and regularly. Ensure water baths have a biocide treatment. Wipe the outside of all media bottles with 70% ethanol before placing them in the BSC [32] [33].

Problem: Consistent contamination across multiple users' cultures. Possible Cause & Solution:

- Compromised BSC or shared reagents. Check the BSC for recent HEPA filter certification and integrity. Ensure shared reagents like trypsin or media are not the source by testing a new, unopened aliquot. Review the BSC placement for drafts from doors, windows, or high-traffic areas [34] [31].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: How long should I run the BSC before starting my work? A: You should purge the cabinet by turning it on and allowing it to run for at least 5 minutes before beginning work. This stabilizes the airflow and removes contaminants from the cabinet interior [34].

Q2: Is it necessary to use a Bunsen burner inside a modern Class II BSC? A: No, and it is generally not recommended. Open flames create turbulence that disrupts the protective laminar airflow pattern and can be a fire hazard. The BSC itself maintains a near microbe-free environment [34].

Q3: How often should I disinfect the incubator, and why is it so important? A: Incubators should be cleaned regularly according to the manufacturer's protocol. The warm, humid environment is an ideal breeding ground for microbes. Contamination in an incubator can spread to all cultures inside, leading to widespread loss [33].

Q4: I followed aseptic technique, but my culture is contaminated. What else could be wrong? A: Consider these often-overlooked sources:

- The Cell Line Itself: The original stock could be contaminated. Test a frozen aliquot.

- Aerosols: Moving quickly or splashing liquids can create aerosols that spread contaminants. Always work slowly and deliberately.

- Water Baths: If you warm media in a water bath, ensure the water is treated and changed regularly, and submerge the bottle fully to prevent contamination from being drawn in during cooling [33].

By integrating these protocols, troubleshooting guides, and best practices into your daily routine, you will fortify your first line of defense, ensuring the reliability and reproducibility of your neuronal research.

In cell culture, particularly for sensitive neuronal studies, the primary engineering control (PEC) is your first and most critical line of defense against contamination. These devices create the controlled environments where your cells are actually handled.

Biosafety Cabinets vs. Other Enclosures

It is crucial to distinguish between different types of enclosures, as using the wrong one can inadvertently introduce contaminants.

Table 1: Comparison of Laboratory Enclosures for Contamination Control

| Enclosure Type | Primary Function | Protects the User? | Protects the Cell Culture? | Air Filtration | Suitable for Infectious Agents? |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Biosafety Cabinet (Class II) | Aerosol control for safe cell culture | Yes [35] | Yes [35] | HEPA-filtered supply and exhaust air [35] | Yes [35] |

| Laminar Flow Hood (Clean Bench) | Product protection only | No - air is blown toward the user [35] | Yes | HEPA-filtered supply air [35] | No [35] |

| Chemical Fume Hood | Removal of chemical fumes and vapors | Yes [35] | No | No HEPA filtration [35] | No [35] |

Cleanroom Classifications and Environments

The secondary engineering control (SEC), or the cleanroom in which your BSC is placed, is equally important. Cleanrooms are classified by the cleanliness of the air based on the number and size of particles permitted per volume of air.

Table 2: Cleanroom ISO Classifications and Particle Counts

| ISO Class | Former US FS 209E Name | Max Particles per Cubic Meter (≥ 0.5 µm) | Typical Garments and Applications [36] |

|---|---|---|---|

| ISO 5 | Class 100 | 3,520 [37] | Full sterile coveralls, hood, mask, boot covers, sterile gloves (double). Critical for aseptic compounding. |

| ISO 7 | Class 10,000 | 352,000 [37] | Hood, face mask, coveralls, gloves, boot covers. Used for medical device manufacturing and buffer areas. |

| ISO 8 | Class 100,000 | 3,520,000 [37] | Hair cover, beard cover, lab coat (frock), shoe covers. Used for packaging, assembly, and anterooms. |

Essential Protocols for Contamination Control

Proper Cleanroom Gowning Procedure

Personnel are the largest source of contamination in a cleanroom. A strict and systematic gowning procedure is non-negotiable [36] [38]. The following workflow ensures that you do not introduce particles from your street clothes into the critical environment.

Detailed Steps for ISO Class 5-7 Gowning:

- Preparation: Before entering the gowning area, remove all personal items such as jewelry, watches, and rings. Do not wear any cosmetics or nail polish [37] [36].

- Hand Hygiene: Wash hands thoroughly with soap and water for at least 15 seconds, covering all hand surfaces. Dry hands completely using a HEPA-filtered air dryer or approved wipes; paper towels are typically prohibited [37].

- Initial Donning (Pre-Gowning Side): In the initial section of the gowning room, don a bouffant cap (ensuring all hair is covered) and a face mask [37] [36].

- Transition: Use a step-over bench to move from the "dirty" side to the "clean" side of the gowning process. This bench acts as a physical barrier to prevent floor contaminants from crossing over [36].

- Don Coverall: Pick up the cleanroom coverall. Be careful to let it touch only the clean floor on the "clean" side of the bench. Tuck the bouffant hood inside the coverall [37] [36].

- Don Booties: Put on cleanroom boot covers, ensuring they overlap and cover the ankles of the coverall [37].

- Don Gloves: Finally, put on cleanroom gloves. The gloves must be pulled over the cuffs of the coverall to create a sealed system, preventing skin flakes from escaping [37] [36].

Biosafety Cabinet Filter Replacement Protocol

A BSC with compromised filters offers false security. Filter replacement is a critical maintenance procedure that must be performed by qualified personnel following a strict decontamination protocol [39].

Pre-Replacement Checklist:

- Qualified Personnel: Is a qualified engineer performing the work? [39]

- Decontamination: Has the BSC been thoroughly decontaminated (fumigated) using a method like Vaporised Hydrogen Peroxide (VHP)? [39]

- Disposal Plan: Has a safe method for disposing of the contaminated old filters been decided? [39]

- Power Off: Has the power to the BSC been completely switched off? [39]

Replacement Steps for Class II BSCs:

- Exhaust HEPA Filter Replacement:

- Remove the frame surround at the top of the BSC, taking care not to damage any airflow sensors.

- Unbolt the filter frame and carefully lift out the old HEPA filter.

- Position the new filter and reverse the process to fit it. Ensure all frame bolts are tightened equally to avoid warping the frame and causing leaks [39].

- Downflow HEPA Filter Replacement:

- From inside the work area, remove any UV light fittings and airflow sensors from the back wall.

- Remove the protective stainless steel mesh cover from the roof.

- Unbolt the HEPA filter frame while providing proper support, and lower it into the work area.

- Fit the new filter to the frame and lift it back into place, again tightening all bolts evenly [39].

- Post-Replacement Certification:

- After the new filters are installed, the cabinet must be re-certified before use. This includes:

- Airflow calibration.

- A DOP (or equivalent) test to check filter integrity and seals.

- A containment test (e.g., Ki-Discus test) to ensure the cabinet maintains containment in line with standards like EN12469 [39].

- All work and test results must be documented in the asset register [39].

- After the new filters are installed, the cabinet must be re-certified before use. This includes:

Troubleshooting Common Contamination Control Issues

FAQ 1: Our cell cultures are frequently contaminated with bacteria, even though we work in a BSC. What are we doing wrong?

- Possible Cause 1: Improper Aseptic Technique.

- Solution: Review and retrain all users on core techniques. Ensure no arms or materials pass over open sterile containers. Always work within the "clean" zone of the BSC (typically 6-8 inches from the grill). Avoid quick, turbulent movements that disrupt the laminar airflow.

- Possible Cause 2: Inadequate BSC Decontamination.

- Solution: Implement a strict decontamination routine. The BSC interior must be decontaminated with an appropriate disinfectant (e.g., 70% ethanol, diluted bleach) for a minimum of 10-15 minutes of contact time before and after every use. All surfaces, including the side and back walls, should be wiped down thoroughly.

- Possible Cause 3: Contaminated Reagents.

- Solution: Always sterilize media by filtration (0.2 µm) even if purchased as "sterile." Qualify your reagent sources. Aliquot reagents to avoid repeatedly using from the same stock bottle.

FAQ 2: We are seeing high particle counts in our ISO 7 cleanroom. Where should we focus our investigation?

- Possible Cause 1: Inadequate Gowning.

- Possible Cause 2: Gown Room Cross-Contamination.

- Possible Cause 3: Unsealed Notepaper or Non-Cleanroom Compatible Materials.

- Solution: Only use cleanroom-compatible paper and pens inside the cleanroom. Standard paper and cardboard are significant sources of particle generation and are prohibited.

FAQ 3: When should the HEPA filters in our Biosafety Cabinet be replaced?

- Answer: Filters are replaced based on one of two triggers, whichever comes first:

- Failed Certification: During the annual certification, if the filters fail the integrity (DOP) test or if the airflow cannot be calibrated to the required specifications due to a clogged filter [39].

- Physical Damage: Any visible physical damage to the filter media or its sealing gaskets.

- Important Note: Filter replacement is not a routine, time-based activity. It should only be performed after a failed test or evident damage, and always by a qualified professional following full cabinet decontamination [39].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Key Reagents and Materials for Aseptic Cell Culture

| Item | Function in Contamination Control |

|---|---|

| 70% Isopropyl Alcohol | Primary disinfectant for wiping down all surfaces inside the BSC and all items introduced into it (flasks, media bottles, etc.). |

| Sterile, Filter-Tip Pipettes | Pre-sterilized and equipped with filters to prevent aerosol contaminants from being drawn into the pipette shaft, protecting both your samples and the instrument. |

| Single-Use, Sterile Centrifuge Tubes | Guarantees a sterile environment for sample preparation and storage, eliminating the risk of cross-contamination from improper washing of reusable tubes. |

| Sterile Cell Culture Media | The nutrient-rich solution for cells. Must be sterile and used with additives (e.g., antibiotics/antimycotics) as required by your protocol. |

| Sterile Phosphate Buffered Saline (PBS) | Used for washing cells without causing osmotic shock. Must be sterile to avoid introducing contaminants during wash steps. |

| Trypsin-EDTA Solution | A sterile enzyme solution used to detach adherent cells from culture vessels for subculturing or analysis. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What are the most common early signs of contamination I can see with a microscope? While some bacterial and fungal contamination is visible to the naked eye as turbidity or floating clumps, microscopic inspection reveals subtler signs. For phase-contrast microscopy, look for small, shimmering dots (bacteria) or thin, filamentous structures (fungi) moving in the spaces between cells. A sudden, unexplained change in cell morphology, such as granulation, vacuolization, or the retraction of neurites in neuronal cultures, can also indicate microbial presence, particularly mycoplasma [40] [41].

Q2: My culture medium is turning acidic (yellow) very quickly, but I see no contaminants. What could be the cause? A rapid pH drop in the absence of visible contamination can have several causes:

- Incorrect CO₂ levels: Verify that the CO₂ concentration in your incubator matches the bicarbonate concentration in your medium [41].

- Overly tight flask caps: Loosen the caps one-quarter turn to allow for proper gas exchange [41].

- High cell density: An over-confluent culture produces metabolic waste too quickly, acidifying the medium. Passage the cells at a lower density [41].

- Mycoplasma contamination: These organisms can alter cell metabolism and culture pH without being visible. Test your culture for mycoplasma [41].

Q3: Why are my primary neurons dying or failing to attach after thawing? Low viability post-thaw is often related to the freezing and thawing process itself.

- Incorrect thawing: Thaw cells quickly but dilute the freezing medium slowly using pre-warmed growth medium [41].

- Poor-quality freezer stock: Use low-passage cells to create new stocks and follow established freezing protocols precisely [41].

- Improper substrate: Ensure culture vessels are properly coated with a suitable attachment factor like poly-d-lysine to facilitate neuronal adhesion and growth [42] [15].

Q4: What do phase-contrast "halo" artifacts mean, and how do they affect segmentation? In positive phase-contrast microscopy, bright halos often appear along the boundaries between the specimen and the medium. These are optical artifacts and do not represent physical cell structures. The presence of these halos, along with "shade-off" effects, can cause automated image segmentation algorithms to fail by creating inaccurate cell boundaries. Advanced image analysis techniques now model this imaging mechanism to restore artifact-free images for more reliable analysis [40].

Troubleshooting Guide

Use the following table to diagnose and address common cell culture issues.

Table 1: Troubleshooting Common Cell Culture Problems

| Observed Problem | Potential Causes | Recommended Solutions |

|---|---|---|

| Rapid pH shift (medium yellow) | Incorrect CO₂ tension, overly tight flask caps, high cell density, bacterial contamination [41] | Check and adjust incubator CO₂, loosen caps, passage cells, test for mycoplasma/bacteria [41]. |

| Poor cell growth/viability | Incorrect or exhausted medium, poor-quality serum, mycoplasma contamination, over-confluency [41] | Use fresh, pre-warmed medium; test new serum lots; test for mycoplasma; passage at lower density [41]. |

| Cells detaching from substrate | Over-trypsinization, mycoplasma contamination, lack of attachment factors [41] | Reduce trypsinization time/amount; test for mycoplasma; ensure proper coating (e.g., poly-d-lysine) [42] [41]. |

| Phase-contrast halo artifacts | Optical effect from difference in refractive index between cells and medium [40] | Recognize as normal artifact; for automated analysis, use software with artifact-correction algorithms [40]. |

| Unexplained changes in cell morphology | Microbial contamination (esp. mycoplasma), incorrect osmotic pressure, toxic components [41] | Perform sterility tests; check osmolality of medium; review all reagent lots and conditions [41]. |

Advanced Monitoring and Detection Protocols

Quantitative Analysis of Automated Detection Systems

Automated systems, particularly those using artificial intelligence (AI), can significantly improve detection rates and accuracy. The following table summarizes performance metrics from a study on automated skin cancer detection, illustrating the potential of such approaches in biomedical image analysis [43].

Table 2: Performance Metrics of AI-Based Segmentation and Classification Algorithms [43]

| Algorithm Category | Specific Algorithm | Key Performance Metric | Result |

|---|---|---|---|

| Segmentation | Adaptive Snake (AS) | Accuracy | 96% |

| Segmentation | Region Growing (RG) | Accuracy | 90% |

| Classification | Artificial Neural Network (ANN) | Accuracy / Sensitivity (Recall) / Specificity | 94% / 92.30% / 95.83% |

| Classification | Support Vector Machine (SVM) | Accuracy / Sensitivity / Specificity | Not fully specified / Lower than ANN |

Protocol: Novel UV Spectroscopy for Early Contamination Detection

This protocol outlines a machine learning-aided method for rapid, non-invasive microbial detection [29].

Principle: Measure the ultraviolet (UV) light absorbance of cell culture fluids. Microbial contamination alters the fluid's absorption pattern. A machine learning model is trained to recognize these patterns, providing a definitive yes/no assessment [29].

Procedure:

- Sample Collection: Aseptically collect a small aliquot of culture supernatant at designated intervals.

- UV Absorbance Measurement: Transfer the sample to a spectrophotometer and measure its UV absorbance spectrum.

- Data Analysis: Input the spectral data into the trained machine learning model.

- Interpretation: The model provides a contamination assessment within 30 minutes.

- Action: If contamination is detected, initiate corrective actions (e.g., use confirmatory RMMs, discard culture). This method serves as a preliminary, continuous safety check to optimize resource use [29].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents for Primary Neuronal Culture and Monitoring [44] [42] [15]

| Reagent / Material | Function / Application |

|---|---|

| Poly-D-Lysine | Coating agent for culture surfaces to promote neuronal attachment [42] [15]. |

| Neurobasal Medium | A optimized, serum-free basal medium designed for the long-term survival of primary neurons [15]. |

| B-27 Supplement | A serum-free supplement essential for neuronal survival and growth, used in Neurobasal medium [44] [15]. |

| GlutaMAX Supplement | A more stable dipeptide substitute for L-glutamine, which reduces the accumulation of toxic ammonia in cultures [41]. |

| Papain | Proteolytic enzyme used for the gentle dissociation of neural tissues to isolate primary neurons [44]. |

| ROCK Inhibitor (Y-27632) | Improves the survival of dissociated neurons by inhibiting apoptosis [44]. |

| Neurotrophic Factors (e.g., BDNF, GDNF, NGF) | Proteins that support the growth, survival, and differentiation of neurons [44]. |

| HEPES Buffer | Provides additional buffering capacity to maintain physiological pH outside a CO₂ incubator [41]. |

Experimental Workflow and Signaling Pathways

The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow for the early detection and troubleshooting of cell culture contamination, integrating both routine and advanced methods.

Early Detection Workflow

In neuronal studies, where subtle changes in metabolism, gene expression, and cell signaling are critically examined, undetected contamination can compromise data integrity and lead to misleading conclusions. While bacterial and fungal contaminants are often readily apparent, mycoplasma and viral contaminants pose a significant challenge due to their cryptic nature [45] [46]. Mycoplasmas, which lack a cell wall, are common contaminants that can alter cell metabolism and cause chromosomal aberrations without causing visible turbidity in the culture medium [46] [47]. Viral contaminants are even more elusive, as they may not cause cytopathic effects yet can still interfere with experimental outcomes and pose a safety risk to laboratory personnel [46]. This guide details the primary methods for detecting these stealthy invaders.

Mycoplasma Detection Methods

PCR-Based Detection

PCR is a powerful molecular technique for amplifying specific DNA sequences, allowing for the sensitive detection of mycoplasma contaminants.

- Principle: This method targets conserved regions of the mycoplasma genome, such as the 16S rRNA gene. In real-time quantitative PCR (qPCR), the accumulation of amplified DNA is monitored each cycle using fluorescent markers, allowing for quantification [45] [48].

- Advantages:

- High Sensitivity: Capable of detecting a very low number of genome copies [45].

- Rapid Results: Provides results in hours, unlike traditional culture methods that can take weeks [45].

- Broad Detection Range: Assays can be designed to detect a wide spectrum of mycoplasma species common in cell culture [45].

- Disadvantages:

Experimental Protocol: SYBR Green qPCR for Mycoplasma Detection

This protocol is adapted from a study developing a sensitive assay for cell culture quality control [48].

- Sample Preparation: Collect supernatant from the cell culture under test. Extract genomic DNA using a commercial DNA extraction kit.

- Primer Design: Design primers to target the 16S-23S Internal Transcribed Spacer (ITS) region or the 16S rRNA gene of Mycoplasma, Acholeplasma, and Ureaplasma species. Validate specificity in silico before use.

- qPCR Reaction Setup:

- Prepare a reaction mix containing SYBR Green I fluorochrome, primers, and the extracted DNA template.

- Positive Control: Use genomic DNA from a known mycoplasma species (e.g., M. arginini, M. hyorhinis).

- Negative Control: Use nuclease-free water instead of template DNA.

- Thermal Cycling:

- Initial Denaturation: 94°C for 4 minutes.

- 35 Cycles of:

- Denaturation: 94°C for 30 seconds.

- Annealing: 54°C for 30 seconds.

- Extension: 72°C for 30 seconds.

- Final Extension: 72°C for 5 minutes.

- Analysis: Analyze the amplification curves and determine the cycle threshold (Ct) values. A positive signal indicates mycoplasma contamination.

DNA Fluorescence Staining

This method uses fluorescent dyes that bind to DNA to reveal mycoplasma contamination under a microscope.

- Principle: The bisbenzimidazole dye Hoechst 33258 or Hoechst 33342 binds preferentially to A-T-rich regions in DNA. When applied to a fixed cell culture, it stains both the host cell's nucleus and any mycoplasma DNA present in the cytoplasm and attached to the cell membrane [46] [47].

- Advantages:

- Relatively quick and simple protocol.

- Does not require specialized molecular biology equipment.

- Disadvantages:

Experimental Protocol: Enhanced Staining with Colocalization

A recent study describes an enhanced method that combines DNA and membrane staining to improve accuracy [49].

- Cell Seeding: Grow the test cells (e.g., neuronal cell lines) on confocal dishes.

- Staining:

- First, stain the cell membrane by incubating the live cells with Wheat Germ Agglutinin (WGA) Oregon Green 488 conjugate (5-10 µg/mL) for 15 minutes at 37°C.

- Then, without fixing, stain the DNA by adding Hoechst 33342 (1 µg/mL) and incubating for another 15 minutes at 37°C in the dark.

- Washing: Gently wash the cells twice with 1X PBS to remove excess dye.

- Imaging: Capture images using a confocal microscope with a 60x oil-immersion objective.

- Analysis: Look for the colocalization of the blue Hoechst signal (mycoplasma DNA) with the green WGA signal (cell membrane). True mycoplasma contamination appears as bright blue spots tightly associated with the green membrane outline. This helps distinguish it from free-floating cytoplasmic DNA debris [49].

Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay (ELISA)

ELISA is an immunoassay that detects specific antigens or antibodies. For mycoplasma, it can be used to detect species-specific antigens in a culture [47].

- Principle: A capture antibody specific to a mycoplasma antigen is coated onto a microplate. If the antigen is present in the test sample, it will bind. A series of enzyme-linked antibodies and substrates are then added, producing a color change that can be measured spectrophotometrically [47].

- Advantages:

- Can be used to screen a large number of samples at once.

- Good specificity and sensitivity [47].

- Disadvantages:

- Requires specific antibodies for different mycoplasma species.

- May not be as universally adopted for cell culture testing as PCR or DNA staining [47].

Experimental Protocol: Direct Antigen Detection ELISA

- Coating: Coat a 96-well plate with an anti-mycoplasma antibody. Incubate overnight, then wash and block the plate to prevent non-specific binding.

- Sample Addition: Add cell culture supernatant or lysate to the wells. Include positive (known mycoplasma antigen) and negative (culture medium only) controls. Incubate to allow antigen binding.

- Detection Antibody: Add an enzyme-conjugated detection antibody that also recognizes the mycoplasma antigen. Incubate and wash.

- Substrate Addition: Add a colorimetric substrate for the enzyme. If the antigen is present, the enzyme will catalyze a reaction, producing a color change.

- Signal Measurement: Stop the reaction and measure the absorbance of each well with a plate reader. A signal above the negative control indicates contamination.

Comparison of Mycoplasma Detection Methods

The table below summarizes the key features of the primary mycoplasma detection methods.

Table 1: Comparison of Mycoplasma Detection Techniques

| Method | Principle | Time to Result | Sensitivity | Key Advantage | Key Disadvantage |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PCR/qPCR | Amplification of mycoplasma DNA | 2.5 - 5 hours [45] | Very High (as low as 50-100 copies/mL) [48] | High sensitivity and speed | Cannot distinguish viable from non-viable cells [45] |

| DNA Staining (Hoechst) | Fluorescent dye binding to DNA | 1 - 2 hours | Moderate | Simple and fast protocol | Prone to false positives from cellular debris [49] |

| Enhanced Colocalization | DNA & cell membrane co-staining | 1 - 2 hours [49] | High | Reduces false positives by localizing signal [49] | Requires confocal microscopy |

| ELISA | Antibody-based antigen detection | 4 - 6 hours (estimate) | Good [47] | High throughput for many samples | Requires species-specific antibodies [47] |

| Microbial Culture | Growth on enriched agar | 28+ days [45] | High (for cultivable species) | Considered a historical "gold standard" | Extremely slow; some species are non-cultivable [45] |

Virus Detection Methods

Viral contamination is a major concern, especially when working with primary neuronal tissues or cell lines derived from primates.

- Principle of PCR for Viruses: Reverse Transcription PCR (RT-PCR) or qRT-PCR is the most common method. It involves first converting the viral RNA genome into complementary DNA (cDNA) using reverse transcriptase, followed by amplification with virus-specific primers [51].

- Challenges: Viral contamination is notoriously difficult to detect without specific testing, as it may not cause visible changes in the culture. It can originate from the original tissue sample, serum, or other biological reagents [46].

Troubleshooting Guides & FAQs

PCR Troubleshooting Guide

Table 2: Common PCR/qPCR Issues and Solutions

| Problem | Potential Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| No Amplification | Failed reaction components, incorrect thermal cycling conditions, or enzyme inhibitors [52]. | Check all component concentrations and prepare a fresh pre-mix. Verify the PCR program settings. Add BSA (0.3%) to neutralize potential inhibitors [52] [53]. |

| False Positive Signal | Contamination from amplicons (carryover) or other positive samples [53]. | Use aerosol-resistant pipette tips and physically separate pre- and post-PCR areas. Use a dedicated set of reagents and equipment. Employ uracil-DNA-glycosylase (UNG) to degrade carryover contaminants [53]. |

| High Background/Non-specific Bands | Non-specific primer binding, insufficiently optimized annealing temperature, or excessive template [53]. | Verify primer specificity and design. Optimize the annealing temperature using a gradient PCR. Titrate the template concentration to the recommended amount [53]. |

| Poor Replicate Reproducibility | Pipetting errors, uneven thermal block temperature, or incomplete sample mixing [52]. | Calibrate pipettes and ensure proper pipetting technique. Use a thermal cycler with a validated block. Thaw and mix all reagents thoroughly before use [52]. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: My neuronal cell culture looks healthy and grows at a normal rate, but my experimental results are inconsistent. Should I test for mycoplasma? Yes. Mycoplasma contamination is often chronic and asymptomatic, not necessarily killing the cells but causing subtle yet significant changes in cell metabolism, gene expression, and function. These alterations can directly lead to inconsistent and unreliable data in sensitive neuronal studies [45] [47].

Q2: I got a positive Hoechst stain with many extranuclear spots, but my PCR test was negative. What does this mean? This discrepancy strongly suggests that the Hoechst stain is yielding a false positive. The fluorescent spots are likely due to cytoplasmic DNA from other sources, such as apoptotic nuclear fragmentation or micronuclei. The enhanced colocalization staining protocol (using Hoechst with WGA) is recommended to confirm if the DNA is truly associated with the cell membrane, which is characteristic of mycoplasma [49].

Q3: How often should I screen my cell cultures for mycoplasma? It is strongly recommended to implement a routine testing schedule. For frequently used and valuable cell lines, such as neuronal models, testing every two weeks to once a month is advisable. All new cell lines arriving in the lab and all cell banks should be tested before they are put into use [47].

Q4: Can I use antibiotics to eliminate mycoplasma from my precious neuronal cell line? While possible, treatment with specific anti-mycoplasma antibiotics (e.g., BM-Cyclin, Plasmocin) is not always successful and can be stressful to the cells. The treatment typically takes 1-3 weeks, and you must rigorously confirm eradication post-treatment. Prevention through strict aseptic technique and regular screening is far more reliable [54] [50].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Reagents for Mycoplasma and Virus Detection

| Reagent / Kit | Function | Example Products |