A Comprehensive Guide to In Vivo Microdialysis Probe Implantation: Protocol, Optimization, and Applications

This article provides a detailed guide for researchers and drug development professionals on in vivo microdialysis probe implantation.

A Comprehensive Guide to In Vivo Microdialysis Probe Implantation: Protocol, Optimization, and Applications

Abstract

This article provides a detailed guide for researchers and drug development professionals on in vivo microdialysis probe implantation. It covers foundational principles, from the technique's basis in passive diffusion to its application in measuring unbound drug and endogenous compound concentrations in the brain and peripheral tissues. A step-by-step methodological protocol for stereotaxic surgery and implantation in awake, freely behaving animals is outlined, with a focus on chronic preparations and species-specific considerations. Critical troubleshooting sections address pervasive challenges like non-specific binding of hydrophobic compounds, probe recovery calibration, and blood-brain barrier integrity. Finally, the guide explores advanced validation techniques, including combination with PET imaging and LC-MS analysis, to ensure data accuracy and translational relevance in pharmacokinetic and neurochemical research.

Understanding Microdialysis: Principles, Advantages, and Research Applications

The extracellular fluid (ECF) constitutes the internal environment of all multicellular animals, providing the critical medium for substance exchange between the blood and cells [1]. This fluid compartment, comprising approximately 20% of body weight in a young adult male, consists primarily of interstitial fluid that surrounds cells and blood plasma [1]. Passive diffusion serves as a fundamental physical process governing the movement of molecules within this compartment, driven by random molecular motion from areas of higher concentration to areas of lower concentration without cellular energy expenditure [2] [3].

In vivo microdialysis leverages this core principle to sample molecules from the ECF of living tissues. The technique employs semi-permeable membranes that allow molecules to diffuse along their concentration gradients from the ECF into the perfusion fluid, enabling researchers to monitor changes in analyte concentrations over time in awake, freely-behaving animals [4] [5]. This application note details the theoretical foundations, practical protocols, and technical considerations for employing passive diffusion principles in microdialysis experimentation, providing a framework for reliable in vivo sampling of extracellular biomarkers.

Theoretical Foundation

Principles of Passive Diffusion

Passive diffusion represents the simplest mechanism by which molecules cross semi-permeable membranes. During this process, a molecule dissolves in the phospholipid bilayer, diffuses across it, and then dissolves in the aqueous solution at the membrane's opposite side [2]. The net flow of molecules is always down their concentration gradient—from a compartment with a high concentration to one with a lower concentration of the molecule [2]. This process is nonselective, allowing any molecule capable of dissolving in the membrane matrix to cross and equilibrate between the inside and outside of a cell or sampling device [2].

The rate of passive diffusion depends on several key factors:

- Extent of the concentration gradient: Greater concentration differences yield more rapid diffusion rates [3]

- Molecular characteristics: Smaller, hydrophobic molecules diffuse more readily than larger, hydrophilic ones [2]

- Temperature: Higher temperatures increase molecular energy and diffusion rates [3]

- Solvent density: Increased density of the solvent medium decreases diffusion velocity [3]

- Membrane properties: Pore size, thickness, and material composition significantly impact permeability [5]

Molecular Properties Governing Diffusion

Molecular characteristics profoundly influence diffusion capacity through semi-permeable membranes. The phospholipid bilayer presents a hydrophobic barrier that preferentially allows passage of nonpolar, lipid-soluble substances while restricting hydrophilic, charged molecules [2] [3].

Table 1: Molecular Properties Impacting Diffusion Through Semi-Permeable Membranes

| Molecular Characteristic | High Diffusion Capacity | Low Diffusion Capacity | Primary Constraint |

|---|---|---|---|

| Size | Small molecules (<100 Da) | Large molecules (>1000 Da) | Physical exclusion by membrane pores |

| Lipid Solubility | High hydrophobicity | High hydrophobicity | Ability to dissolve in lipid bilayer |

| Charge | Uncharged molecules | Charged molecules | Repulsion by charged membrane components |

| Polarity | Nonpolar substances | Polar substances | Energetic cost of partitioning into hydrophobic environment |

Gases such as O₂ and CO₂, hydrophobic molecules like benzene, and small polar but uncharged molecules including H₂O and ethanol diffuse readily across phospholipid bilayers [2]. In contrast, larger uncharged polar molecules such as glucose and charged molecules of any size require specific transport proteins for membrane crossing [2]. These principles directly inform microdialysis probe design and membrane selection for target analytes.

Microdialysis Methodology

Fundamental Technique

Microdialysis is a minimally invasive sampling technique that employs the principles of passive diffusion to recover molecules from the extracellular space [5]. The core component is a microdialysis probe featuring a semi-permeable membrane at its tip that is implanted into the target tissue [4]. The system is perfused with a solution that closely matches the ionic composition of the extracellular fluid (such as artificial cerebrospinal fluid or Ringer's solution) at flow rates typically ranging from 0.1-5 µL/min [4] [5].

As the perfusion fluid passes through the probe, extracellular molecules diffuse across the membrane along their concentration gradients, collecting in the dialysate that exits through the outlet tubing for subsequent analysis [5]. The technique enables continuous monitoring of analyte concentrations in specific tissue compartments over extended periods, with subjects able to behave normally during sampling [5].

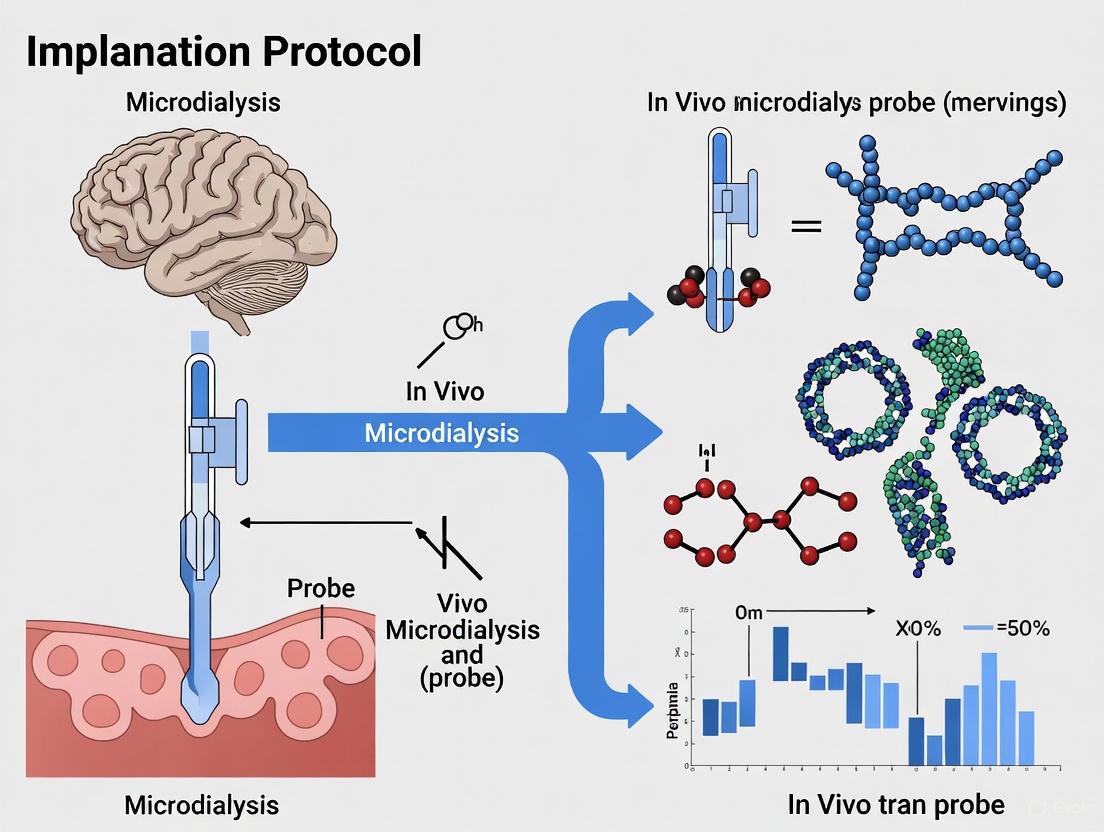

Figure 1: Fundamental principle of microdialysis sampling based on passive diffusion along concentration gradients between extracellular fluid and perfusion medium.

Probe Design and Membrane Characteristics

Microdialysis probes employ a concentric design where perfusion fluid enters through an inlet tubing, flows downward to the probe tip, then travels upward through the space between the dialysis membrane and outer tubing before exiting through the outlet [6]. This design creates a continuous flow path that maintains the concentration gradient essential for efficient sampling.

The molecular weight cut-off (MWCO) of the dialysis membrane is a critical parameter determining which molecules can pass through. Standard probes offer various MWCO options:

- 6-20 kDa: Suitable for small molecules like neurotransmitters, metabolites [6]

- 55-100 kDa: Intermediate size molecules [7]

- 500 kDa-3 MDa: Large molecules such as proteins and peptides [4] [7]

Table 2: Microdialysis Probe Characteristics for Different Molecular Weight Ranges

| Target Analyte Class | Example Molecules | Membrane MWCO | Typical Recovery Range | Optimal Flow Rate |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Small molecules | Glucose, lactate, acetylcholine | 6-20 kDa | 15-25% [6] | 1-2 µL/min |

| Neurotransmitters | Dopamine, glutamate, GABA | 20 kDa | 10-20% | 0.5-2 µL/min |

| Intermediate peptides | Angiotensin II, substance P | 55-100 kDa | 5-15% [7] | 0.5-1.5 µL/min |

| Large proteins | Tau, α-synuclein, cytokines | 500 kDa-3 MDa [4] | 2-6% [6] | 0.1-0.5 µL/min |

Membrane materials vary in their diffusion characteristics and include polysulfone, polyarylethersulphone, polyethersulfone, and regenerated cellulose [5] [6]. Material selection impacts recovery efficiency, with regenerated cellulose membranes typically used for smaller molecules and polyethersulfone membranes preferred for larger molecules due to their higher porosity and reduced adhesion tendencies [5].

Experimental Protocols

Guide Cannula Implantation Surgery

Objective: To surgically implant a guide cannula for subsequent microdialysis probe insertion in target brain regions of laboratory animals.

Materials Required:

- Stereotaxic apparatus with animal adaptor

- Guide cannula (e.g., CMA polyurethane guides) [7]

- Surgical tools (scalpel, forceps, drill)

- Anesthetic agents (e.g., chloral hydrate, 400 mg/kg intraperitoneal) [4] [8]

- Dental cement and bone screw

- Heating pad for thermal support

- Vet ointment for eye protection

Procedure:

- Anesthetize the animal and confirm anesthetic depth by toe pinch reflex test [4].

- Secure the animal in the stereotaxic apparatus using ear bars and nose clamp, ensuring head stability [4].

- Apply vet ointment to eyes to prevent dryness during anesthesia [4].

- Make a sagittal incision on the skin over the skull and retract tissue to expose the skull surface [4].

- Level the skull in both anterior-posterior and left-right planes using a drill attached to the stereotaxic manipulator [4].

- Identify bregma and lambda landmarks and calculate coordinates for the target brain region using a standard brain atlas [4] [8].

- Drill a burr hole at the target coordinates, ensuring the diameter accommodates the guide cannula [4].

- Drill an additional hole in the contralateral parietal bone and insert a bone screw to help secure the dental cement [4].

- Position the guide cannula assembly on the stereotaxic adaptor and lower the cannula slowly into the brain at the calculated coordinates and depth [4].

- Mix and apply dental cement around the cannula and bone screw, completely covering the exposed skull area [4].

- Allow the cement to fully harden (12-20 minutes) before removing the stereotaxic adaptor [4].

- Insert a dummy probe into the guide cannula to prevent occlusion [4].

- House the animal individually and monitor until regaining consciousness, providing analgesic support as needed [4].

- Allow 1-2 days recovery for acute experiments or up to 2 weeks for sleep-wake studies requiring habituation [4].

Critical Considerations:

- Maintain strict aseptic technique throughout the procedure

- Ensure precise skull leveling for accurate coordinate targeting

- Verify cannula placement depth according to species-specific brain anatomy

- Provide appropriate postoperative analgesia and monitoring

Microdialysis Probe Preparation and Setup

Objective: To prepare and calibrate microdialysis probes for in vivo sampling of extracellular analytes.

Materials Required:

- Microdialysis probes (e.g., CMA 7, 11, or 20 depending on application) [7]

- Syringe pumps (CMA 100/400 or equivalent) [9]

- Perfusion fluid (aCSF or Ringer's solution)

- Bovine serum albumin (BSA) for protein sampling [4]

- Ethanol (70-100%) for probe activation

- Distilled water for flushing

- Fraction collector for sample collection [5]

Procedure:

- Probe Quality Check: Fill a 1 mL syringe with distilled water and connect to the probe outlet. Cover vent holes and depress the plunger gently to infuse water through the probe. Verify that water appears from the probe inlet without membrane leakage [4].

- Probe Activation: Submerge the probe membrane in ethanol (70-100%) for two seconds to condition the membrane, then flush again with distilled water [4].

- Perfusion Buffer Preparation: Prepare artificial CSF (1.3 mM CaCl₂, 1.2 mM MgSO₄, 3 mM KCl, 0.4 mM KH₂PO₄, 25 mM NaHCO₃, 122 mM NaCl, pH 7.35) [4]. For large molecule sampling, add BSA to 4% concentration to prevent analyte adhesion and limit fluid loss through large-pore membranes [4]. Filter through a 0.1 µm syringe filter to remove aggregates [4].

- System Priming: Fill the syringe with perfusion buffer and connect to the inlet tubing. Run the syringe pump to fill the entire tubing system with buffer, eliminating air bubbles [4].

- Push-Pull Setup (for high MWCO membranes): For probes with cut-off >1000 kDa, configure a push-pull system using a syringe pump to perfuse (push) and a roller/peristaltic pump to collect (pull) [4]. This prevents pressure accumulation and ultrafiltration fluid loss [4].

- Flow Rate Optimization: Set appropriate flow rates based on target analytes (0.1-0.5 µL/min for proteins, 1-2 µL/min for small molecules) [5].

- In Vitro Recovery Determination: Before in vivo use, calibrate each probe by placing it in a standard solution with known analyte concentrations. Calculate relative recovery as: (Analyte concentration in dialysate) / (Analyte concentration in standard solution) × 100 [6].

Figure 2: Workflow for microdialysis probe preparation and calibration before in vivo implantation.

In Vivo Microdialysis Sampling

Objective: To collect extracellular analytes from conscious, freely-behaving animals over timed intervals.

Materials Required:

- Microdialysis system with push-pull capability [4]

- Liquid swivel with balance arm for freely-moving animals

- Fraction collector or automated sample handler

- Microvials for sample collection

- Cooling system for sample preservation (4°C)

Procedure:

- Gently remove the dummy probe from the guide cannula and insert the calibrated microdialysis probe, securing it in place [4].

- Begin perfusion with the optimized flow rate and allow the system to equilibrate for 1-2 hours to establish stable baseline conditions [5].

- Connect the outlet tubing to a fraction collector maintained at 4°C to preserve sample integrity [5].

- Collect dialysate samples at predetermined intervals (typically 10-30 minutes depending on analyte stability and concentration) [5].

- For pharmacological interventions, administer compounds systemically or via reverse microdialysis (adding compounds to the perfusion buffer) [4].

- Following sample collection, remove the probe, euthanize the animal, and verify probe placement histologically.

- Store samples at -80°C until analysis if not processed immediately.

Analytical Considerations:

- Select appropriate analytical methods based on target analytes (HPLC-ECD for monoamines, ELISA for proteins, mass spectrometry for untargeted analysis) [5]

- Account for sample dilution and recovery rates when calculating extracellular concentrations

- Include appropriate controls for system validation and background subtraction

The Scientist's Toolkit

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Key Reagents and Materials for Microdialysis Experiments

| Item | Specification/Composition | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Artificial CSF | 1.3 mM CaCl₂, 1.2 mM MgSO₄, 3 mM KCl, 0.4 mM KH₂PO₄, 25 mM NaHCO₃, 122 mM NaCl, pH 7.35 [4] | Physiological perfusion fluid matching brain ECF composition | Maintains ionic homeostasis during sampling |

| Ringer's Solution | 148 mM NaCl, 4 mM KCl, 1.2 mM CaCl₂, 0.85 mM MgCl₂ [5] | Alternative perfusion fluid with physiological salt concentrations | Higher calcium than standard aCSF; suitable for neurotransmitter sampling |

| Bovine Serum Albumin | 4% in aCSF [4] | Osmotic agent and blocking protein | Prevents adhesion of hydrophobic molecules; reduces fluid loss through large-pore membranes |

| CMA Microdialysis Probes | Various MWCO (6 kDa - 3 MDa) and membrane lengths (1-30 mm) [7] | Semi-permeable interface for molecular diffusion | Select based on target analyte size and tissue region dimensions |

| Polysulfone Membranes | 30 kDa MWCO custom probes [6] | Semi-permeable barrier for analyte sampling | Suitable for small molecules and peptides; alternative to commercial probes |

| Chloral Hydrate | 400 mg/kg intraperitoneal [4] [8] | Surgical anesthetic for probe implantation | Provides stable anesthesia duration for stereotaxic procedures |

| Dental Cement | Polyurethane-based cranioplastic cement [4] | Secure guide cannula to skull | Creates stable, long-term implantation platform |

Technical Considerations and Limitations

Implantation Trauma and Tissue Response

Probe implantation inevitably causes localized tissue damage, creating a trauma layer adjacent to the probe membrane that alters the normal neurochemical environment [8]. This traumatized tissue demonstrates compromised neurotransmitter release and uptake capacity, potentially distorting measurements of extracellular concentrations [8]. Histological studies reveal that implantation induces both short- and long-term biochemical changes in nearby neural tissue, including alterations in transporter function and neurotransmitter dynamics [8].

The trauma effect is particularly significant for efficiently cleared neurotransmitters like dopamine, where the extraction fraction measured by microdialysis may underestimate actual extracellular concentrations due to impaired uptake mechanisms in the damaged tissue perimeter [8]. To mitigate these effects, researchers should:

- Allow appropriate recovery time between surgery and sampling (1-14 days depending on study design) [4]

- Use the smallest feasible probe diameter to minimize tissue displacement [7]

- Validate measurements with complementary techniques when possible (e.g., voltammetry for monoamines) [8]

Recovery Considerations and Quantitative Interpretation

The concentration of analytes in the dialysate represents only a fraction of their true extracellular concentration, described as the relative recovery [5]. Multiple factors influence recovery efficiency:

- Flow rate: Lower flow rates (0.1-0.5 µL/min) increase relative recovery but extend collection intervals [5]

- Membrane characteristics: Longer membranes and larger pore sizes enhance recovery [5]

- Molecular properties: Larger, more hydrophobic molecules exhibit lower recovery rates [5] [6]

- Tortuosity: Diffusion pathways through the extracellular space are indirect, slowing equilibration [5]

For accurate quantitative assessment, researchers should determine probe recovery individually for each experimental setup using no-net-flux methods or in vitro calibration [8] [6]. The no-net-flux approach involves perfusing the probe with different concentrations of the target analyte and identifying the point where inflow and outflow concentrations equalize, indicating the true extracellular concentration [8].

Advanced Applications: Push-Pull Perfusion for Large Molecules

Traditional microdialysis faces limitations when sampling large molecules such as proteins and peptides due to their slow diffusion characteristics and membrane adhesion tendencies [4]. The push-pull modification addresses these challenges by employing two pumps: one to push perfusion fluid into the probe and another to pull dialysate from the outlet [4]. This configuration prevents pressure accumulation within high MWCO probes that would otherwise cause ultrafiltration and fluid loss into the surrounding tissue [4].

Specialized probes with pressure-canceling vent holes (e.g., AtmosLM probes) further optimize this system by eliminating pressure differentials that could cause membrane leakage [5]. For large molecule sampling, perfusion fluids typically include additives like BSA (0.15-4%) to minimize surface adhesion and maintain stable recovery rates throughout extended sampling periods [4] [5].

In vivo microdialysis is a catheter-based sampling technique that enables continuous monitoring of unbound molecules in the interstitial fluid of specific tissues in awake, freely behaving animals [10] [11]. This methodology is particularly invaluable in preclinical drug development and neuroscience research, as it provides serial data on pharmacologically active drug concentrations and endogenous biomarkers from a well-defined anatomical site over time [12] [10]. A principal strength of this technique is its inherent alignment with the 3Rs principle of animal experimentation—Replace, Reduce, Refine [12]. By allowing for continuous sampling in a single animal and the implantation of multiple probes to sample different tissues or brain regions simultaneously, microdialysis significantly reduces the number of animals needed for statistically powerful experiments while refining methodologies to minimize animal distress [12] [10].

This application note details the core advantages of this approach and provides a detailed protocol for its implementation, enabling researchers to leverage this powerful technique for robust and ethical in vivo research.

Core Advantages and Quantitative Benefits

The integration of continuous sampling in freely moving animals with the 3Rs framework offers tangible and significant benefits for research quality and animal welfare. The table below summarizes these key advantages.

Table 1: Key Advantages of Microdialysis in Freely Behaving Animals

| Advantage | Description | Impact on Research & 3Rs |

|---|---|---|

| Serial Sampling in Awake Animals | Enables collection of data from awake, freely behaving animals, eliminating confounding effects of anesthesia on physiology and behavior [13] [14]. | Refinement: Improves animal welfare and data quality. Provides more physiologically relevant data correlated with behavior [10]. |

| Continuous, Longitudinal Data | Allows for the collection of multiple serial samples from a single animal over hours or days [14] [11]. | Reduction: Each animal serves as its own control, reducing biological variability and the total number of animals required [12]. |

| Multiple-Site Sampling | Permits the implantation of multiple probes in a single animal (e.g., two brain regions or a brain region and a blood vessel) [10]. | Reduction: Maximizes data obtained per animal, drastically reducing the group sizes needed for complex study designs [10]. |

| Sample Cleanliness | The semi-permeable membrane excludes cells and large macromolecules, providing protein-free samples ready for direct analysis [10] [15]. | Refinement: Simplifies analytical procedures and reduces potential sample degradation, leading to more reliable results. |

The quantitative impact of this approach on experimental design is demonstrated in the following table, which outlines feasible configurations in different rodent models.

Table 2: Experimental Configuration and 3Rs Impact

| Parameter | Mouse | Rat | Impact on 3Rs |

|---|---|---|---|

| Maximum Probe/Lines | 2 lines total [10] | 3 lines total [10] | Enables complex, multi-compartment pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic (PK/PD) studies with fewer animals. |

| Typical Configuration | 1-2 brain regions, or 1 brain region + jugular vein cannula [10] | 2 brain regions + jugular vein or cisterna magna cannulation [10] | Reduction: A single rat can provide simultaneous data on brain PK in two regions and systemic plasma PK. |

| Experiment Duration | Feasible to sample over weeks [10] | Feasible to sample over weeks, potentially months [10] | Reduction: Long-term studies can be performed with a stable cohort of animals, avoiding the need for multiple cohorts sacrificed at different time points. |

Experimental Workflow and Protocol

The following diagram and detailed protocol describe the standard procedure for conducting a microdialysis experiment in a freely behaving animal, from surgical preparation to sample analysis.

Protocol: In Vivo Microdialysis in Freely Moving Rodents

Title: Continuous Sampling of Brain Interstitial Fluid in Awake, Freely Behaving Rats for PK/PD Analysis.

Objective: To serially collect unbound analyte from the brain extracellular space of a freely behaving rat before and after systemic administration of a test compound, enabling calculation of pharmacokinetic parameters and the unbound brain-to-plasma partition coefficient (Kp,uu).

Materials:

- Animals: Adult Sprague-Dawley or Wistar rats.

- Microdialysis System: Guide cannula, microdialysis probe (e.g., CMA 7, CMA 12), perfusion tubing, syringe pump, fraction collector [13] [16].

- Perfusate: Artificial Cerebrospinal Fluid (aCSF: 145 mM NaCl, 2.68 mM KCl, 1.40 mM CaCl₂, 1.01 mM MgSO₄, 1.55 mM Na₂HPO₄, 0.45 mM NaH₂PO₄, pH 7.4) or Ringer's solution [13] [16].

- Analytical Instrumentation: UPLC-MS/MS system or other sensitive detection method [12] [16].

Procedure:

- Surgical Implantation: Anesthetize the rat and stereotactically implant a guide cannula above the target brain region (e.g., striatum, prefrontal cortex). Secure the cannula to the skull with dental acrylic and skull screws [17] [16].

- Recovery Period: Allow the animal to recover for a minimum of 24-48 hours. This critical period allows for the recovery of the blood-brain barrier and the reduction of acute tissue trauma and inflammation around the implant site, which is essential for obtaining physiologically relevant data [15].

- Probe Insertion and Perfusion: On the experimental day, carefully insert the microdialysis probe through the guide cannula so the semi-permeable membrane extends into the target brain region. Connect the probe to a syringe pump via perfusion tubing and perfuse with aCSF at a low, constant flow rate (e.g., 0.5 - 1.0 µL/min) [13] [16].

- Baseline Sample Collection: Place the animal in a freely moving cage (e.g., equipped with a Raturn system). Allow the system to equilibrate for 1-2 hours. Subsequently, collect dialysate samples at predefined intervals (e.g., 20-60 minutes, collecting 10-30 µL per fraction) into a refrigerated fraction collector to establish baseline analyte levels [13] [14].

- Intervention and Post-Intervention Sampling: Administer the test compound via a predetermined route (e.g., intraperitoneal, oral gavage). Continue collecting serial dialysate samples for the duration of the experiment to capture the PK profile [14].

- Sample Analysis and Data Calculation:

- Immediately store collected samples at -80°C until analysis [13].

- Analyze analyte concentration in each fraction using an appropriate analytical method (e.g., UPLC-MS/MS for drugs, HPLC-ECD for monoamines, ELISA for peptides) [10] [16].

- Calculate the unbound brain concentration (Cu,brain) by correcting the dialysate concentration for the probe's recovery rate. The unbound plasma-to-brain partition coefficient (Kp,uu) is calculated as Kp,uu = AUCu,brain / AUCu,plasma, where AUC is the area under the concentration-time curve for the unbound fraction in brain and plasma, respectively [12].

Troubleshooting Notes:

- Low Analytic Recovery: For hydrophobic compounds prone to non-specific binding to tubing and membranes, consider adding agents like bovine serum albumin (BSA, 0.5-1.5%) or low concentrations of DMSO (0.01-0.1%) to the perfusate to improve recovery [12].

- Probe Calibration: Determine the relative recovery for each probe before in vivo experiments using retrodialysis or other calibration methods to ensure accurate quantification [12] [18].

The Scientist's Toolkit

Successful implementation of a microdialysis study relies on several key reagents and materials. The following table outlines essential solutions and their critical functions.

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Microdialysis

| Reagent/Solution | Function | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Artificial Cerebrospinal Fluid (aCSF) | The physiological perfusate that mimics the ionic composition of brain extracellular fluid, enabling diffusion of analytes without net fluid exchange [12] [11]. | Must be isotonic and buffered to pH 7.4. Ascorbic acid (0.25 mM) may be added as an antioxidant [16]. |

| Bovine Serum Albumin (BSA) | Added to aCSF (typically 0.5-1.5%) to minimize non-specific binding of hydrophobic drugs to the microdialysis apparatus, thereby improving recovery rates [12]. | Critical for obtaining reliable data for compounds with lipophilic characteristics, such as selinexor and ulixertinib [12]. |

| Dimethyl Sulfoxide (DMSO) | Used at low concentrations (e.g., 0.01-0.1%) in the perfusate to enhance the solubility and recovery of highly lipophilic compounds [12]. | Concentration must be kept low to avoid cytotoxic effects and disruption of the blood-brain barrier. |

| Probe Calibration Standards | Solutions of known analyte concentration used in vitro (retrodialysis) to determine the relative recovery of each probe, which is required to calculate true extracellular concentrations [12] [18]. | The recovery rate is probe- and analyte-specific and is vital for translating dialysate concentration to actual in vivo concentration. |

Microdialysis has established itself as a robust and versatile minimally-invasive sampling technique for the continuous measurement of unbound analyte concentrations in the extracellular fluid of virtually any tissue [19]. This powerful method provides researchers with unprecedented access to dynamic biochemical processes in living tissues, enabling both sampling of endogenous molecules and monitoring exogenous compound distribution. The technique's unique capability to quantify pharmacologically active free drug fractions at their site of action has made it indispensable in both preclinical drug development and clinical research [12] [20]. As microdialysis systems have evolved, applications have expanded from fundamental neuroscience to diverse fields including oncology, metabolic disorders, and infectious diseases, with the global microdialysis probe market projected to reach approximately $750 million by 2033, growing at a CAGR of 8.5% [21].

The fundamental principle underlying microdialysis involves the implantation of a small catheter featuring a semipermeable membrane into the tissue of interest. The probe is continuously perfused with an aqueous solution resembling the ionic composition of surrounding tissue fluid at low flow rates (typically 0.1-5 μL/min). Solutes below the membrane's molecular weight cutoff cross this barrier via passive diffusion along concentration gradients, allowing collection of dialysate for analysis [19]. This continuous sampling capability provides unparalleled temporal resolution for monitoring dynamic processes, while the membrane acts as a physical barrier protecting tissue from turbulent flow and high-molecular-weight substances [22].

Table 1: Key Application Areas of Microdialysis

| Application Domain | Primary Analytes Measured | Research Objectives |

|---|---|---|

| Neuroscience & CNS Drug Development | Neurotransmitters (dopamine, serotonin, glutamate, GABA), metabolites, energy substrates (glucose, lactate, pyruvate) [22] [19] | Elucidate neurotransmitter systems in cognition/behavior [17], assess blood-brain barrier penetration [12] [20], measure target engagement |

| Neuro-oncology & Cancer Therapeutics | Chemotherapeutic agents (e.g., erlotinib, temozolomide), metabolites, neurotransmitters with tumor-modulatory effects (glutamate, GABA) [23] [24] [25] | Determine intratumoral drug disposition [23], monitor tumor metabolism (glucose, lactate) [24], identify resistance mechanisms |

| Toxicology & Drug Metabolism | Xenobiotics and their metabolites | Characterize tissue-specific pharmacokinetics/pharmacodynamics, assess organ exposure and toxicity |

| Peripheral Tissue Monitoring | Glucose, hormones, cytokines, drugs | Monitor subcutaneous glucose in diabetes [19], assess topical drug bioavailability in skin [19], measure tissue-specific inflammation |

CNS Neurotransmitter Research Applications

The application of microdialysis in central nervous system research has revolutionized our understanding of neurochemical processes in living brain tissue. Originally developed for and predominantly applied to neuroscience, this technique enables real-time monitoring of neurotransmitter dynamics in specific brain regions during various behavioral states, pharmacological interventions, and disease processes [22]. The ability to simultaneously measure multiple neurotransmitter systems provides crucial insights into their complex interplay underlying cognitive functions and neurological disorders.

Recent methodological advances have significantly expanded the scope of CNS microdialysis applications. A groundbreaking 2025 study demonstrated a novel implementation in awake, behaving non-human primates, allowing simultaneous quantification of multiple neurotransmitters including GABA, glutamate, norepinephrine, epinephrine, dopamine, serotonin, and choline from small sample volumes (<20 μL) during different cognitive states [17]. This approach revealed subtle concentration variations between behavioral states and complex correlation patterns between neurotransmitter pairs, highlighting the sophisticated neurochemical regulation of cognitive processes.

Experimental Protocol: Neurotransmitter Monitoring in Behaving Primates

Research Objective: To simultaneously measure concentration dynamics of multiple cortical neurotransmitters during different cognitive states in awake, behaving rhesus macaques [17].

Materials and Equipment:

- Microdialysis probes with appropriate molecular weight cutoff (typically 20-30 kD)

- Removable guide insets compatible with standard electrophysiology implant

- Precision micropump capable of low flow rates (0.3-1.0 μL/min)

- Artificial cerebrospinal fluid (aCSF) perfusate: 147 mM NaCl, 2.7 mM KCl, 1.2 mM CaCl₂, 0.85 mM MgCl₂ in purified water [20]

- UPLC-ESI-MS (Ultra-Performance Liquid Chromatography with Electrospray Ionization-Mass Spectrometry) system

- Fraction collector for sample preservation

Procedure:

- Probe Implantation: Semi-chronically implant microdialysis guides into target brain region (e.g., visual middle temporal area MT) using removable insets within a standard recording chamber.

- System Equilibration: On experimental day, implant probes and perfuse with aCSF at 0.5 μL/min for 1-2 hours to establish baseline.

- Sample Collection: Collect dialysate fractions at 30-60 minute intervals during defined behavioral states (e.g., 'active' during cognitive tasks vs. 'inactive' during rest).

- Sample Analysis: Analyze samples using UPLC-ESI-MS with optimized methods for simultaneous neurotransmitter quantification.

- Data Analysis: Normalize neurotransmitter concentrations, calculate changes between behavioral states, and determine correlation patterns between neurotransmitter pairs.

Critical Considerations:

- Maintain consistent sample handling and storage conditions to prevent analyte degradation

- Use appropriate calibration methods (e.g., no-net-flux) to determine in vivo recovery rates

- Employ statistical analyses accounting for multiple comparisons when examining multiple neurotransmitters

Cancer Drug Penetration and Intratumoral Disposition

The application of microdialysis in oncology has emerged as a powerful approach to overcome the critical challenge of determining whether chemotherapeutic agents adequately penetrate tumor tissue to reach therapeutic concentrations at their site of action [23]. This is particularly crucial for brain tumors where the blood-brain barrier (BBB) and blood-tumor barrier significantly restrict drug access, contributing to the disappointing clinical results of many promising neuro-oncology clinical trials [23] [24]. Microdialysis enables direct measurement of unbound, pharmacologically active drug fractions within tumor interstitial fluid, providing critical data that cannot be inferred from plasma pharmacokinetics or even cerebrospinal fluid measurements [23] [20].

In brain cancer research, microdialysis has been applied to study various chemotherapeutic agents including temozolomide, erlotinib, and other targeted therapies [23] [24]. These investigations have revealed that drug concentrations in tumor ECF often represent only a fraction of plasma levels, with considerable inter-individual variability [23]. Furthermore, studies have established relationships between intratumoral drug concentrations and target modulation, as demonstrated in a clinical trial where patients receiving erlotinib 150 mg/day failed to achieve adequate intratumoral levels or inhibit EGFR phosphorylation, resulting in no clinical benefit [23]. Beyond monitoring drug disposition, microdialysis also enables characterization of the tumor metabolic microenvironment, with measurements of glucose, lactate, glutamate, and glycerol providing insights into bioenergetic states and response to therapy [24].

Experimental Protocol: Assessing Anticancer Drug Brain Penetration

Research Objective: To determine the unbound brain-to-plasma partition coefficient (Kp,uu) of hydrophobic anticancer drugs using cerebral microdialysis in rodent models [12].

Materials and Equipment:

- CMA7 or CMA8 microdialysis probes (CMA Microdialysis) or MD-2211 probes (Bioanalytical Systems Inc.)

- Precision syringe pump with low pulsation

- Fluorinated ethylene propylene (FEP) or polyetheretherketone (PEEK) tubing to minimize nonspecific binding

- Ringer's solution with 0.5%-1.5% bovine serum albumin (BSA), potentially with 0.01%-0.1% DMSO for hydrophobic compounds

- UPLC-MS/MS system for drug quantification

- Temperature-controlled fraction collector

Procedure:

- Probe Implantation: Stereotactically implant microdialysis guide cannula into target brain region (e.g., striatum, tumor tissue) under anesthesia.

- In Vivo Recovery Determination: After probe insertion, perform retrodialysis calibration by perfusing with drug solution (e.g., 100 ng/mL) at 0.5 μL/min and calculating recovery as (Cperfusate - Cdialysate)/Cperfusate.

- Experimental Sampling: Following systemic drug administration, perfuse probes with blank aCSF or Ringer's solution containing BSA at 0.5 μL/min.

- Simultaneous Blood Sampling: Collect plasma samples at time points matching dialysate collection intervals.

- Sample Analysis: Quantify drug concentrations in dialysate and plasma using UPLC-MS/MS.

- Data Calculation: Calculate Kp,uu as AUCbrain,ECF/AUCplasma,unbound, where AUC represents area under the concentration-time curve.

Critical Considerations:

- For hydrophobic compounds (e.g., actinomycin D, selinexor, ulixertinib), include surface modification strategies and additive to minimize nonspecific binding

- Verify drug stability under experimental conditions (temperature, light exposure)

- Perform nominal concentration tests to assess drug loss due to adsorption to system components

Table 2: Microdialysis Calibration Methods for Drug Disposition Studies

| Calibration Method | Principle | Advantages | Limitations | Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Retrodialysis [12] [19] | Perfuse with drug solution and measure disappearance from probe | Accounts for in vivo mass transfer resistance; relatively simple | Requires drug-free tissue (not for endogenous compounds); assumes symmetric diffusion | Exogenous compounds in clinical/preclinical settings |

| No-Net-Flux [19] | Perfuse with multiple drug concentrations and determine no-net-flux point | Highly accurate at steady-state; direct measure of extracellular concentration | Time-consuming; requires steady-state conditions | Endogenous compounds; validation studies |

| Low-Flow-Rate Method [19] | Measure recovery at different flow rates and extrapolate to zero flow | Conceptually straightforward | Long collection times for sufficient sample volume; impractical for unstable compounds | Small molecules with adequate stability |

| Dynamic No-Net-Flux [19] | Combine data from multiple subjects perfused with single concentrations | Enables recovery determination under non-steady-state conditions | Requires multiple subjects/animals; complex experimental design | Drug challenge studies with endogenous compounds |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Successful microdialysis experiments require careful selection of specialized materials and reagents optimized for specific research applications. The appropriate choice of probe characteristics, perfusion solutions, and analytical methods significantly impacts data quality and experimental outcomes. Current market analysis indicates a growing demand for multi-channel microdialysis probes that enable simultaneous monitoring of multiple brain regions or analytes, with innovations focusing on enhanced sensitivity, selectivity, and biocompatibility [21] [26].

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Microdialysis Applications

| Category | Specific Products/Solutions | Function & Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Microdialysis Probes | Single-channel, dual-channel, multi-channel probes [21] [26] | Sampling from extracellular fluid; selection based on target region size and desired spatial resolution |

| Membrane Types | CMA 20 (20 kD cutoff), CMA 100 (100 kD cutoff) [24] | Molecular weight cutoff determines analyte range; high cutoff membranes enable protein/peptide sampling |

| Perfusion Solutions | Artificial cerebrospinal fluid (aCSF), Ringer's solution, with/without carrier proteins (0.5-1.5% BSA) [12] [20] | Maintain tissue homeostasis; BSA reduces nonspecific binding of hydrophobic compounds |

| Calibration Standards | Analytical grade neurotransmitters, drug compounds, isotope-labeled internal standards | Quantification of absolute extracellular concentrations; correction for recovery variations |

| Analytical Instruments | UPLC-ESI-MS [17], UPLC-MS/MS [12], HPLC with electrochemical detection | High-sensitivity quantification of multiple analytes in small volume samples |

| System Components | Fluorinated ethylene propylene (FEP) tubing [12], precision syringe pumps, fraction collectors | Minimize analyte adsorption; ensure consistent low flow rates; maintain sample integrity |

Advanced Methodological Considerations

Challenges and Optimization Strategies

The application of microdialysis, particularly for hydrophobic compounds or in clinical settings, presents several methodological challenges that require careful consideration and optimization. Hydrophobic drugs with pronounced nonspecific binding to microdialysis system components represent a particular challenge, leading to low recovery rates and substantial carry-over effects [12]. Comprehensive investigations with compounds such as actinomycin D, selinexor, and ulixertinib have demonstrated that strategies including surface coating and optimized materials can significantly enhance data reliability [12].

For clinical applications in neuro-oncology, microdialysis has been safely used in patients intraoperatively, in intensive care units, and increasingly in ambulatory settings [24]. The development of portable, low-volume micropumps that can be worn by ambulatory patients has expanded monitoring possibilities, with typical perfusion rates now at 0.3 μL/min enabling 100% fractional recovery for many analytes [24]. When applying microdialysis in pathological tissue such as brain tumors, researchers must consider that tortuosity (the geometric complexity of extracellular space) differs from normal brain, potentially affecting analyte recovery and requiring cautious data interpretation [24].

Integration with Complementary Techniques

The research value of microdialysis is significantly enhanced when integrated with complementary analytical and imaging techniques. The combination of microdialysis with ultra-performance liquid chromatography and mass spectrometry enables simultaneous measurement of multiple neurotransmitters and metabolites from small sample volumes, as demonstrated in non-human primate studies quantifying GABA, glutamate, norepinephrine, epinephrine, dopamine, serotonin, and choline from <20 μL samples [17]. This multi-analyte capability provides comprehensive insights into complex neurochemical interactions that would be difficult to discern from single-analyte approaches.

Furthermore, the integration of microdialysis with modern imaging techniques such as positron emission tomography allows correlation of extracellular drug concentrations with intracellular distribution and target engagement [19]. This combined approach is particularly valuable in oncology drug development, where it can elucidate relationships between drug penetration, target modulation, and therapeutic response. As microdialysis continues to evolve, emerging trends include the development of smart probes with integrated sensors, wireless systems for chronic monitoring, and expanded applications in novel therapeutic areas including immunology and metabolic disorders [21] [26].

In vivo microdialysis is a minimally invasive sampling technique critical for continuous monitoring of unbound analyte concentrations in the extracellular fluid of specific tissues [12] [13]. The reliability and validity of data generated from microdialysis experiments are fundamentally governed by the appropriate selection and configuration of the microdialysis probe. This application note details the essential components of microdialysis probes—membrane types, molecular weight cut-off (MWCO), and geometric configurations—within the context of a broader thesis on in vivo implantation protocols. Aimed at researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, this document provides structured quantitative data, detailed experimental protocols, and visual tools to guide probe selection and optimization, ensuring the acquisition of physiologically relevant and reproducible data.

Core Probe Components and Characteristics

The performance of a microdialysis probe is determined by the interplay of its three core physical characteristics: the membrane material, the molecular weight cut-off, and the probe's physical configuration.

Membrane Types and Material Properties

The membrane material is pivotal in determining analyte recovery and susceptibility to fouling. Different materials offer distinct advantages and limitations.

- Cellulose-Based Membranes (Cuprophane/Regenerated Cellulose): These are traditional, hydrophilic membranes commonly used in neuroscientific applications. An example is the CMA/11 probe with a 1 mm cuprophane membrane [27]. Their hydrophilic nature minimizes non-specific binding for many hydrophilic compounds but may be less suitable for hydrophobic molecules [12].

- Polyethersulfone (PES) Membranes: PES membranes, such as those found in the MAB 4.15.2 probe, are another common choice [27]. They offer good mechanical stability.

- Polysulfone (PSU) and Modified Membranes: Membranes fabricated from polysulfone, often with additives like polyvinylpyrrolidone (PVP), are widely used [28]. PVP enhances hydrophilicity and hemocompatibility, reducing undesired protein fouling. These membranes can be further modified with antifouling surface treatments, such as mono(ethylene glycol) (MEG) silane, to create a hydrophilic barrier that prevents protein adsorption and pore occlusion, thereby maintaining permeability in complex biological environments like blood serum [28].

- Polyacrylonitrile Membranes: These membranes have been used in "loop type" probes designed for subcutaneous tissue, offering another material option for specific applications [29].

Table 1: Common Microdialysis Membrane Materials and Their Properties

| Membrane Material | Key Properties | Advantages | Considerations | Common Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cuprophane/Regenerated Cellulose | Hydrophilic | Low non-specific binding for hydrophilic analytes | Potential for higher biofouling; challenged by hydrophobic drugs | Neuroscience; sampling of neurotransmitters [13] [27] |

| Polyethersulfone (PES) | Mechanically robust, moderate hydrophilicity | Good chemical stability | May require optimization for hydrophobic compounds | General in vivo sampling [27] |

| Polysulfone (PSU)/PVP Blend | Can be engineered for asymmetry and porosity | Tunable permeability; amenable to antifouling coatings | Native form can be hydrophobic | Hemodialysis; sampling from complex fluids [28] |

| Surface-Modified Membranes | Hydrophilic antifouling layer (e.g., MEG) | Significantly reduced protein adsorption and fouling | Coating process adds complexity | Long-term implantation; sampling from serum/blood [28] |

Molecular Weight Cut-Off (MWCO)

The MWCO is a critical parameter that defines the size-selectivity of the membrane.

- Definition: MWCO is defined as the lowest molecular weight (in Daltons) at which 90% of a solute is retained by the membrane [30]. It is important to note that this definition is not absolute and can sometimes refer to 80% retention [30].

- Selection Guidance: The MWCO must be selected to retain large macromolecules (like proteins) while allowing the analyte of interest to pass through freely. Commercially available microdialysis probes typically offer MWCOs ranging from 1,000 to 300,000 Da [30]. For neurochemical monitoring, common MWCOs are around 6 kDa and 13 kDa [13] [27]. For sampling drugs or metabolites, the membrane's MWCO should be significantly larger than the molecular weight of the target analyte to ensure efficient recovery.

- Limitations: MWCO is a useful guide but has limitations. The value is often determined using standard molecules like dextrans or polyethylene glycol, which may have different geometries (e.g., linear vs. globular) compared to the target analyte, affecting actual retention [31]. Furthermore, membrane-analyte interactions such as adsorption can alter effective retention, particularly for hydrophobic compounds [12] [31].

Table 2: Typical MWCO Ranges and Applications

| MWCO Range | Typical Analytic Categories | Example Applications |

|---|---|---|

| 1 - 6 kDa | Small molecules, neurotransmitters, drugs, most amino acids | Neurotransmitter monitoring (e.g., dopamine, acetylcholine); pharmacokinetic studies of small molecule drugs [13] [32] |

| 10 - 30 kDa | Peptides, small proteins, larger drug molecules | Cytokine sampling; biomarker discovery in pathological tissues |

| > 50 kDa | Larger proteins and biotherapeutics | Sampling of antibodies or protein-based therapeutics in tumors |

Probe Configurations and Dimensions

The physical design of the probe influences its fluid dynamics, recovery efficiency, and tissue compatibility.

- Concentric Design: This is the most common configuration for cerebral and tissue microdialysis [12] [27]. It features a concentric arrangement where an inner cannula delivers the perfusate to the tip of the probe, which is surrounded by a semi-permeable membrane. The dialysate then flows back through an outer shaft. This design is robust and widely used in commercial systems like those from CMA Microdialysis [33].

- Side-by-Side (Linear) Design: In this configuration, the inlet and outlet tubing run parallel, with a section of the membrane between them forming the "window" for dialysis [33] [27]. This design can be fabricated in-lab and allows for longer membrane lengths, which can increase relative recovery [27] [29].

- Loop-Type Probes: These probes utilize longer membranes (e.g., 20–100 mm) arranged in a loop, significantly increasing the membrane surface area. This design provides higher relative recovery (>50%) at higher flow rates (>5 µL/min) and is particularly useful for sampling from subcutaneous tissue in therapeutic drug monitoring [29].

- Microfabricated Probes: Emerging technologies allow for the fabrication of ultra-small probes in silicon. These probes can be as small as 45 µm thick and 180 µm wide, drastically reducing tissue damage and enabling sampling from microenvironments not accessible with conventional probes [32]. They incorporate a buried U-shaped microfluidic channel and a nanoporous membrane, representing a significant advancement in spatial resolution [32].

Table 3: Microdialysis Probe Configurations and Performance Characteristics

| Probe Configuration | Typical Dimensions | Relative Recovery | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Concentric | Diameter: >220 µm [32]; Membrane: 1-4 mm | Varies with flow rate and MWCO; e.g., ~8.9% for cocaine in brain at 1.2 µL/min [34] | Standard, robust design; suitable for deep tissue implantation | Larger diameter causes more tissue damage; limited design flexibility |

| Side-by-Side (Linear) | Membrane length can be customized (e.g., 2 mm [27]) | Can be optimized via membrane length and flow rate | Simpler construction; suitable for custom lab fabrication | Potentially less robust for certain implantations |

| Loop-Type | Membrane length: 20-100 mm [29] | High; >50% at >5 µL/min [29] | High recovery rates; suitable for subcutaneous space | Larger size may not be suitable for delicate tissues like brain |

| Microfabricated | e.g., 45 µm thick × 180 µm wide [32] | Low (2-7%) at very low flow rates (100 nL/min) [32] | Minimal tissue damage; high spatial resolution; potential for functional integration | Complex fabrication; lower recovery requires highly sensitive analytics |

Experimental Protocols for Probe Characterization

Ensuring the reliability of microdialysis data requires rigorous pre-experimental characterization of the probes. The following protocols are essential for quantifying recovery and identifying potential issues like analyte adsorption.

Protocol for In Vitro Recovery Determination via Retrodialysis

This method is used to estimate the in vivo recovery of a probe for an exogenous compound prior to an animal experiment [12].

1. Principle: The probe is immersed in a solution containing the analyte of interest, which is also included in the perfusate. The disappearance of the analyte through the membrane (retrodialysis) is measured, and the relative recovery is calculated based on the difference between the perfusate concentration and the dialysate concentration.

2. Research Reagent Solutions:

- Perfusate: Ringer's solution or artificial cerebrospinal fluid (aCSF).

- Analyte Stock Solution: A known concentration of the target drug/compound dissolved in perfusate.

- External Medium: The same analyte solution as the perfusate, maintained at a known concentration in a beaker.

- Equipment: Microdialysis pump, fraction collector, analytical instrument (e.g., UPLC-MS/MS).

3. Step-by-Step Procedure:

1. Prepare a solution of the analyte (e.g., 100 ng/mL) in Ringer's solution. For hydrophobic compounds, adding a carrier protein like Bovine Serum Albumin (BSA, 0.5%-1.5%) or a low concentration of organic solvent (e.g., 0.01-0.1% DMSO) may be necessary to minimize non-specific binding [12].

2. Immerse the microdialysis probe in a beaker containing the same analyte solution (the external medium). Maintain the solution at a constant temperature (37°C) with continuous, gentle stirring.

3. Perfuse the probe with the analyte solution at the desired flow rate (e.g., 0.5-1.0 µL/min) using a precision pump.

4. Allow the system to equilibrate for approximately 1 hour.

5. Collect three or more consecutive dialysate fractions over defined intervals (e.g., 1 hour each).

6. Analyze the concentration of the analyte in the dialysate fractions (Cdialysate) and the original perfusate (Cperfusate) using a sensitive analytical method.

7. Calculate the relative recovery (RR) using the formula for retrodialysis:

RR (%) = [(C_perfusate - C_dialysate) / C_perfusate] × 100 [12].

Protocol for Assessing Analyte Adsorption to the System

Hydrophobic compounds are prone to non-specific binding (adsorption) to the various surfaces of the microdialysis system (tubing, probe, collection vials), which can lead to significant analyte loss and underestimation of true concentrations [12].

1. Principle: A solution with a known, precise concentration of the analyte is passed through the entire microdialysis setup (or its components), and the recovered concentration is measured. The recovery rate indicates the degree of adsorption.

2. Research Reagent Solutions:

- Test Solution: A known concentration of the analyte (e.g., 100 ng/mL) in Ringer's solution or aCSF.

- Equipment: Microdialysis syringe, tubing (e.g., FEP, PEEK), collection vials (polypropylene, glass), analytical instrument.

3. Step-by-Step Procedure:

- Nominal Concentration Test: Transfer the prepared test solution into different types of collection vials (e.g., polypropylene, plastic microdialysis tubes, glass). Analyze the concentration in each vial after transfer. Recovery is calculated as: (Measured Concentration / Prepared Concentration) × 100 [12]. This identifies losses due to vial adsorption.

- Tubing and System Adsorption Test:

1. Load the test solution into a microdialysis syringe.

2. Pump the solution through a defined length (e.g., 1 m) of the intended tubing (e.g., FEP or PEEK) at the experimental flow rate.

3. Collect samples at the outlet at multiple time points.

4. Also, collect samples directly from the syringe before and after perfusing the tubing.

5. Analyze all samples and calculate recovery for each step to pinpoint the source of adsorption [12].

Visualization and Decision Support

Probe Selection and Optimization Workflow

The following diagram outlines a logical workflow for selecting and optimizing a microdialysis probe based on experimental goals and analyte properties.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

The following table details key materials and reagents essential for the setup and execution of microdialysis experiments, particularly those involving challenging hydrophobic compounds.

Table 4: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Microdialysis

| Reagent/Material | Function/Description | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Artificial Cerebrospinal Fluid (aCSF) | Perfusate that mimics the ionic composition of brain extracellular fluid. Contains NaCl, KCl, CaCl₂, MgSO₄, and buffers [13] [27]. | Standard perfusate for cerebral microdialysis; ensures physiological ionic environment. |

| Ringer's Solution | A balanced salt solution used as a perfusate. | Can be used as an alternative to aCSF; composition can be modified [12]. |

| Bovine Serum Albumin (BSA) | Carrier protein added to perfusate or solutions. | Used at 0.5%-1.5% to minimize non-specific binding of hydrophobic drugs to the system [12]. |

| Dimethylsulfoxide (DMSO) | Organic solvent for solubilizing compounds. | Used at low concentrations (e.g., 0.01-0.1%) to enhance the solubility of hydrophobic drugs in aqueous perfusates [12]. |

| Fluorinated Ethylene Propylene (FEP) Tubing | Plastic tubing for connecting the syringe pump to the probe. | Compared to Polyetheretherketone (PEEK) for its adsorption properties [12]. FEP may exhibit lower binding for some analytes. |

| Polyetheretherketone (PEEK) Tubing | Alternative plastic tubing known for high strength and biocompatibility. | Commonly used; adsorption tests are recommended to select the best tubing for a specific analyte [12]. |

| Antifouling Surface Modifiers | e.g., mono(ethylene glycol) silane. | Forms a hydrophilic monolayer on membrane surfaces to prevent protein adsorption and fouling, crucial for long-term studies in serum or blood [28]. |

Step-by-Step Implantation Protocol: From Stereotaxic Surgery to Chronic Sampling

The success of an in vivo microdialysis experiment is fundamentally determined during the pre-implantation planning phase, specifically through the appropriate selection of the probe and its semipermeable membrane. This selection must be meticulously aligned with the chemical properties of the target analyte, the biological model, and the experimental timeframe. An unsuitable probe can lead to inadequate recovery, significant analyte loss due to non-specific binding, and ultimately, unreliable data. This document provides a structured framework for researchers to navigate the critical parameters of probe and membrane selection, ensuring the acquisition of pharmacologically relevant data from the outset.

The core principle of microdialysis involves the diffusion of substances across a semipermeable membrane driven by a concentration gradient [12]. The probe assembly, encompassing the membrane, tubing, and cannula, is implanted into the target tissue, where a perfusate is circulated at a low, constant flow rate. The unbound analyte in the extracellular fluid passively diffuses into the dialysate, which is collected for analysis [12]. The efficiency of this exchange—the recovery rate—is vulnerable to numerous factors, with probe configuration and membrane composition being paramount.

Key Selection Parameters for Probes and Membranes

Selecting the optimal probe and membrane requires a systematic evaluation of several interconnected factors. The table below summarizes the primary considerations and their implications for experimental design.

Table 1: Key Parameters for Probe and Membrane Selection

| Parameter | Considerations | Impact on Experiment |

|---|---|---|

| Analyte Properties | Molecular weight/size (Da), hydrophobicity, chemical stability (e.g., photostability, thermostability) [12]. | Determines required Molecular Weight Cut-Off (MWCO) and membrane material; hydrophobic compounds require specialized materials to minimize non-specific binding (NSB) [12]. |

| Molecular Weight Cut-Off (MWCO) | Membrane pore size rating; typically 20 kDa for small molecules like neurotransmitters [35] to 100 kDa [36] or 1,000 kDa for peptides/proteins [37]. | Must be sufficiently high to allow analyte passage but low enough to exclude macromolecules and debris that could foul the membrane. |

| Membrane Material | Cuprophane (cellulose), Polyethersulfone (PES), Polyacrylonitrile (PAN), polysulfone [37] [12]. | Influences biocompatibility, recovery efficiency, and propensity for NSB; material choice is critical for hydrophobic compounds [12]. |

| Animal Model & Sampling Site | Species (mouse, rat, etc.), target brain region or peripheral tissue, freely moving vs. anesthetized [37]. | Dictates probe physical dimensions (length, shaft size, weight) and configuration (cannula-based for chronic, linear for peripheral tissues) [37]. |

| Experimental Duration | Acute (hours, under anesthesia) vs. Chronic (days, in freely moving animals) [37]. | Determines probe type and need for a guide cannula; chronic implants risk fouling and foreign body reaction, potentially affecting calibration over time [38]. |

Probe Type Selection Based on Experimental Model

The choice of probe is critically dependent on the experimental model and design. Manufacturers offer a range of probes tailored to specific applications:

- Chronic Experiments in Freely Moving Rodents: For studies involving dopamine, serotonin, acetylcholine, or other small molecules in freely moving animals, cannula-style probes are essential. The CX-i series is optimized for mice due to its lightweight and narrow body, while the FZ probe is ideal for rats or longer mouse experiments, featuring a locking mechanism to prevent dislodgement [37]. These probes are used with a guide cannula that is surgically implanted and protected with a dummy probe during recovery. On the experimental day, the active probe is inserted in seconds, minimizing animal stress [37].

- Acute Experiments Under Anesthesia: For short-term studies in anesthetized animals, the DZ probe is a compact option designed for direct implantation without a guide cannula, making it ideal for use in stereotaxic frames [37].

- Large Molecule Sampling: To measure peptides, proteins, or antibodies, specialized probes like the AtmosLM PEP probe with a 1 million Dalton MWCO membrane are required. These may also include features like a vent to equalize internal pressure and prevent unwanted convection, thereby improving sampling accuracy [37].

- Peripheral Tissue and Specialized Applications: For dermal or vascular work, linear probes with a built-in needle are available to simplify implantation [37]. Furthermore, metal-free probe series exist for studies that involve concurrent MRI or PET imaging, preventing signal interference [37].

Membrane Selection for Analyte-Specific Challenges

The membrane material is a key determinant of recovery and data validity, especially for challenging analytes.

- Hydrophobic Compounds: Drugs like ulixertinib, selinexor, and actinomycin D exhibit a pronounced tendency for non-specific binding to microdialysis system components (tubing, membrane), leading to low recovery and substantial carry-over effects [12]. Mitigation strategies include the use of surface coatings, optimized membrane materials, and the addition of agents like bovine serum albumin (BSA, 0.5%-1.5%) or DMSO (0.01%-0.1%) to the perfusate to reduce binding [12].

- Neuropeptides and Proteinaceous Analytes: The detection of low-concentration, labile peptides like enkephalins requires high-sensitivity methods. While MWCO is a primary factor, specialized analytical techniques such as methionine oxidation followed by solid-phase extraction and nano-liquid chromatography/mass spectrometry (nLC-MS) are employed to stabilize and accurately quantify these molecules [39].

Quantitative Data and Calibration Methods

Accurate quantification requires calibrating the recovery efficiency of each probe, which is the ratio between the dialysate concentration and the actual extracellular concentration [12]. The choice of calibration method depends on the analyte and experimental constraints.

Table 2: Microdialysis Probe Calibration Methods

| Calibration Method | Principle | Advantages | Disadvantages | Calculation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| In Vitro Dialysis [12] | Probe immersed in a stirred solution of known analyte concentration. | No animals needed; easy to control conditions. | Does not account for in vivo mass transfer resistance in tissue. | RR = C_dialysate / C_external |

| Retrodialysis (In Vivo/In Vitro) [12] [38] | An internal standard (or the drug itself) is added to the perfusate and its disappearance is measured. | Accounts for mass transfer resistance in vivo; relatively straightforward. | Requires a drug-free brain (for in vivo); assumes diffusion is symmetric. | RR = (C_perfusate - C_dialysate) / C_perfusateC_ECF = C_dialysate / RR |

| No-Net-Flux Method [12] | The probe is perfused with varying concentrations of the analyte to find the point where there is no net flux. | Well-investigated; provides a direct measure. | Requires a steady state and a large number of samples/animals. | (Intercept calculation from a concentration curve) |

| Ultra-Slow Flow Rate Method [12] | The flow rate is reduced to a very low level (e.g., 0.1-0.3 µL/min) to increase equilibration. | Increases recovery rate; useful for low-flow applications. | Results in very small sample volumes, demanding highly sensitive analytics. | RR = (1 - exp(-PeAQ)) × 100 |

Experimental Protocols for Probe Setup and Validation

Protocol: In Vitro Probe Recovery Assessment via Retrodialysis

This protocol is used to determine the baseline recovery of a probe for a specific analyte prior to in vivo experimentation [12].

- Preparation: Immerse the microdialysis probe in a beaker containing a stirred blank Ringer's solution, maintained at 37°C. For hydrophobic compounds, add BSA (e.g., 0.5%-1.5%) or DMSO to the solution to mimic in vivo conditions and minimize NSB [12].

- Perfusion: Perfuse the probe with a solution of the target analyte (e.g., 100 ng/mL) at the intended experimental flow rate (e.g., 0.5 μL/min) using a precision syringe pump.

- Equilibration: Allow the system to equilibrate for a sufficient period (e.g., 60-90 minutes) to ensure stable diffusion.

- Sample Collection: Collect three consecutive dialysate fractions at defined intervals (e.g., 1 hour).

- Analysis and Calculation: Quantify the analyte concentration in the dialysate (Cdialysate) and the original perfusate (Cperfusate) using a sensitive analytical method (e.g., UPLC-MS/MS). Calculate the relative recovery (RR) using the formula:

RR = (C_perfusate - C_dialysate) / C_perfusate

Protocol: Surgery and Probe Implantation in Rodent Brain

This protocol details the stereotaxic implantation of a microdialysis probe for sampling in the brain, such as the medial Prefrontal Cortex (mPFC) or Nucleus Accumbens (NAc) [40] [35] [41].

- Anesthesia and Positioning: Deeply anesthetize the rodent (e.g., using isoflurane at 4% for induction, 2-3% for maintenance) and securely mount it in a stereotaxic instrument. Place the animal on a heating pad to maintain body temperature.

- Surgical Exposure: Make a sagittal incision to expose the skull. Clean and dry the skull surface. Identify Bregma and Lambda and level the skull.

- Guide Cannula Implantation (For Chronic Studies): For chronic studies in freely moving animals, drill a hole for the guide cannula above the target region. Implant the guide cannula (e.g., AG guide for FZ probes) and secure it to the skull with anchoring screws and dental cement [37]. Insert a dummy probe to maintain patency.

- Probe Implantation (Acute or Post-Recovery):

- For acute studies: Drill a hole at the calculated stereotaxic coordinates. Gently lower the probe (e.g., a DZ probe) directly into the brain tissue [37].

- For chronic studies: After a recovery period (e.g., 48 hours), gently remove the dummy probe and insert the active microdialysis probe (e.g., CX or FZ) through the guide cannula [37].

- Perfusion and Securing: Throughout the implantation, continuously perfuse the probe with artificial cerebrospinal fluid (aCSF; e.g., 149 mM NaCl, 2.8 mM KCl, 1.2 mM CaCl₂, 1.2 mM MgCl₂, 0.25 mM ascorbic acid, 5.4 mM D-glucose, pH 7.2-7.4) [40] at a minimal flow rate. Once correctly positioned, secure the probe assembly to the skull with additional dental cement.

- Recovery and Experiment: Allow the animal to recover in its home cage for the prescribed time before commencing microdialysis sampling.

Workflow Visualization

The following diagram illustrates the core decision-making process for selecting a microdialysis probe based on experimental parameters.

Diagram 1: Probe Selection Workflow

The following diagram outlines the key stages of a microdialysis experiment, from preparation to data analysis.

Diagram 2: Microdialysis Experimental Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

A successful microdialysis experiment relies on a suite of specialized reagents and materials. The following table details essential components and their functions.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Microdialysis

| Reagent/Material | Function/Application | Example Protocols & Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Artificial Cerebrospinal Fluid (aCSF) [40] | Standard perfusate solution that mimics the ionic composition of brain extracellular fluid, minimizing tissue disturbance during sampling. | 149 mM NaCl, 2.8 mM KCl, 1.2 mM CaCl₂, 1.2 mM MgCl₂, 0.25 mM ascorbic acid, 5.4 mM D-glucose (pH 7.2-7.4) [40]. |

| Ringer's Solution [35] | A physiological salt solution commonly used as a perfusate, sometimes with modifications like Lactated Ringer's [36]. | Consists of (in mmol/l): 140 NaCl, 1.2 CaCl₂, 3.0 KCl, 1.0 MgCl₂ [35]. |

| Bovine Serum Albumin (BSA) [12] | Added to perfusate (0.5%-1.5%) to saturate non-specific binding sites on tubing and membrane, crucial for recovering hydrophobic drugs [12]. | Used in retrodialysis calibration and in vivo sampling for compounds like actinomycin D and ulixertinib [12]. |

| Dimethyl Sulfoxide (DMSO) [12] | Organic solvent used in low concentrations (e.g., 0.01-0.1%) to enhance the solubility of highly hydrophobic compounds in aqueous perfusates [12]. | Requires careful optimization to avoid cellular toxicity and ensure compatibility with the analytical system. |

| Internal Standards (for calibration) [12] [38] | Used in retrodialysis to determine in vivo recovery. The loss of the standard from the perfusate is assumed to equal the recovery of the analyte. | Examples include 2-deoxyglucose (for metabolism assessment), antipyrine, and vitamin B12 [38]. Isotopically labeled standards (e.g., D4-Met-Enk) are used for LC-MS [39]. |

| Perchloric Acid [41] | Added to collection vials to stabilize easily oxidizable neurotransmitters like dopamine, preventing degradation prior to analysis. | Samples are collected directly into a small volume (e.g., 10 µL) of 0.1 M perchloric acid [41]. |

| High MWCO Membranes (e.g., AtmosLM PEP) [37] | Specialized membranes with a high molecular weight cut-off (e.g., 1,000 kDa) for sampling large biomolecules like peptides, proteins, and antibodies. | Feature a vent to equalize internal pressure, preventing convection and improving accuracy for large molecules [37]. |

| Custom-Microdialysis Probes [37] [39] | Probes can be customized with alternative membrane materials (PES, PAN), shaft sizes, and membrane lengths to suit specific experimental needs [37]. | Custom, smaller probes can be fabricated to minimize tissue damage, similar to fiber photometry probes [39]. |

Animal Preparation and Anesthesia Protocols for Rodents and Larger Species

In vivo microdialysis is a cornerstone technique for monitoring the chemistry of the extracellular space in living tissues, enabling the sampling of unbound analytes such as neurotransmitters, hormones, and pharmaceuticals directly from the site of action [42]. The successful implantation of a microdialysis probe and the subsequent acquisition of physiologically relevant data are critically dependent on appropriate animal preparation and the selection of an anesthetic protocol that ensures animal welfare while minimizing interference with the experimental outcomes. The choice of anesthesia is a significant confounder, as it can modulate neurovascular coupling, cerebral blood flow, and baseline neuronal metabolism, thereby threatening the scientific validity of the data [43]. This application note provides a detailed framework for animal preparation and anesthesia protocols tailored for microdialysis probe implantation in both rodents and larger species, framed within the context of a broader thesis on in vivo microdialysis research.

Anesthesia Protocols for Rodents

Selecting an appropriate anesthetic regimen is paramount for rodent models. The ideal protocol provides stable surgical anesthesia, minimizes physiological disturbances, and, where possible, allows for a swift recovery to enable studies in awake, freely moving animals.

Inhalant Anesthesia: Isoflurane

Inhalant anesthesia, particularly with isoflurane, is widely used due to its reliability and the capacity for rapid induction and recovery [44].

- Procedure: Mice are anesthetized with isoflurane delivered in 100% oxygen at a flow rate of 0.6 L/min. A delivered concentration of 1.3%, which is the EC50 for B6 mice, is used as a target for surgical anesthesia. The concentration should be adjusted based on the monitoring of physiological parameters to maintain a consistent plane of anesthesia [13].

- Monitoring and Maintenance: Core body temperature and breathing rate should be recorded at regular intervals (e.g., every 12.5 minutes) and maintained within a physiological range throughout the procedure using a heating pad [13].

- Application: This method is suitable for acute sample collection during anesthesia. For recovery surgeries and experiments in awake animals, the probe is inserted after the animal has recovered from the anesthetic [13].

Injectable Anesthesia Protocols

Injectable combinations are valuable, especially in environments where vaporizer systems are impractical. Recent studies have systematically compared various mixtures for surgical procedures.

Table 1: Comparison of Injectable Anesthetic Protocols for Mouse Surgery

| Anesthetic Combination | Dosage and Route | Surgical Anesthesia Duration (median, min) | Key Characteristics | Reversal Agent |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ketamine-Medetomidine | Ketamine (100 mg/kg) + Medetomidine (0.3 mg/kg) [44] | 120 {100-125} [44] | Longest surgical duration; requires analgesia supplementation. | Atipamezole (0.3 mg/kg, s.c.) [44] |

| Alfaxalone-Medetomidine | Alfaxalone (80 mg/kg, s.c.) + Medetomidine (0.3 mg/kg, s.c.) [44] | 53 {25-100} [44] | Reliable for surgical cardiac models; compatible with reversal. | Atipamezole (0.3 mg/kg, s.c.) [44] |

| Alfaxalone-Mede-Buprenorphine | Alfaxalone (80 mg/kg) + Medetomidine (0.3 mg/kg) + Buprenorphine (0.075 mg/kg), s.c. [44] | Similar to Alfaxalone-Mede [44] | Provides enhanced analgesia; recommended for ischemia-reperfusion surgery. | Atipamezole (0.3 mg/kg, s.c.) [44] |

- General Procedure for Injectables: Drugs are extemporaneously diluted in saline (0.9%). After injection, mice are placed back in their cage until the righting reflex is lost. They are then positioned on a heating pad (target 37.5°C) and provided with 30% O2-enriched air via a mask [44].

- Reversal of Anesthesia: Administration of atipamezole (an α2-adrenergic receptor antagonist) significantly reduces both recovery time and total immobilization time, which is beneficial for animal welfare [44].

Anesthesia and Protocols for Larger Species

While the principles of anesthesia are similar, working with larger species like non-human primates (NHPs) requires specialized approaches for prolonged experiments in awake, behaving animals.

- Chronic Implantation for Awake Behaving Studies: A semi-chronic implantation method is used in rhesus macaques. Guide cannulae are implanted stereotactically, allowing for the insertion of microdialysis probes via removable insets while the animal is awake and engaged in cognitive tasks [17]. This setup permits reliable, simultaneous measurements of multiple neurotransmitters from small sample volumes (<20 µl) in the sensory cortex during different behavioral states [17].