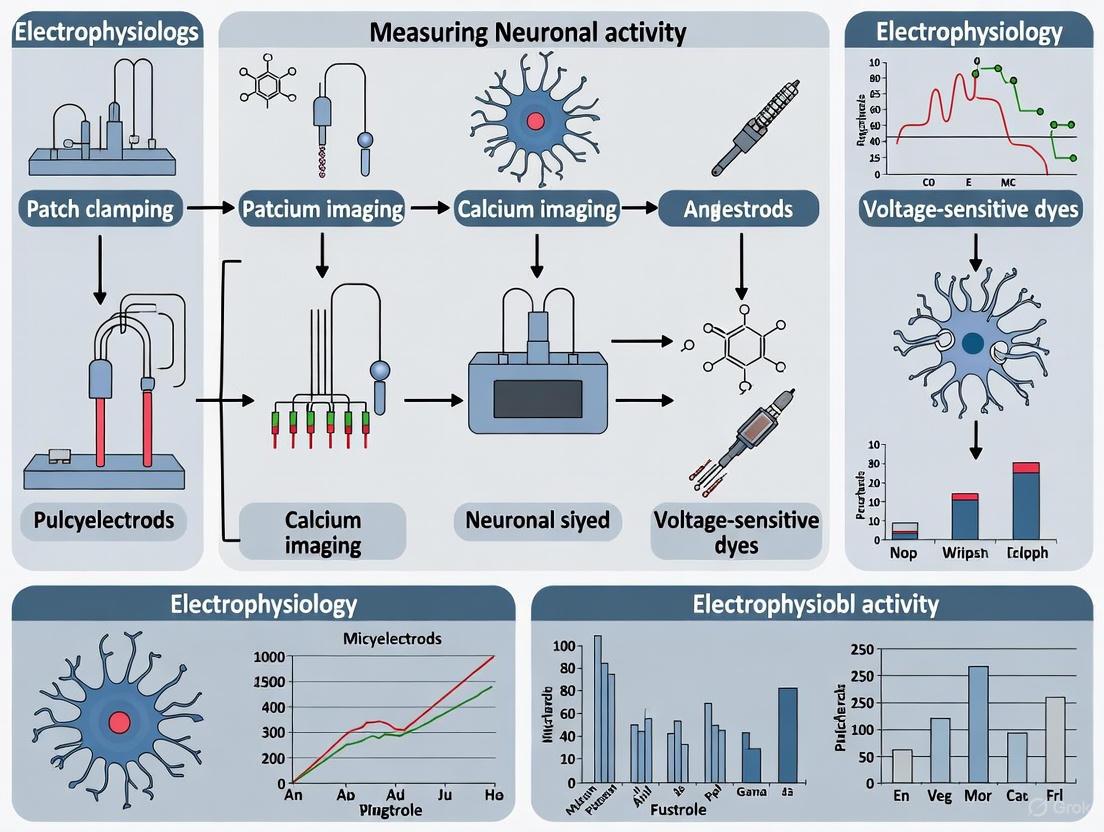

A Comprehensive Guide to Electrophysiology Methods for Measuring Neuronal Activity

This article provides a comprehensive overview of electrophysiology techniques for measuring neuronal activity, tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals.

A Comprehensive Guide to Electrophysiology Methods for Measuring Neuronal Activity

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of electrophysiology techniques for measuring neuronal activity, tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals. It covers foundational principles, from the basic electrical properties of neurons to the role of ion channels. The guide details core methodologies like patch-clamp recording, microelectrode arrays (MEAs), and voltage/current-clamp, alongside their applications in basic research, drug discovery, and disease modeling. It also offers practical troubleshooting advice for improving experimental outcomes and discusses frameworks for validating results and comparing the strengths of various techniques. By synthesizing traditional methods with recent advancements in automation and high-throughput screening, this resource aims to be an essential reference for designing and executing robust electrophysiology studies.

Understanding the Fundamentals: The Electrical Language of Neurons

Fundamental Concepts of Neuronal Excitability

Neuronal excitability is a fundamental property of neurons, defined as their ability to generate action potentials in response to various stimuli [1]. This capability enables neurons to transmit and process information throughout the nervous system. The excitability of a neuron determines how it responds to synaptic inputs, generates action potentials, and communicates with other neurons [1].

Types of Neuronal Excitability

There are two primary types of neuronal excitability [1]:

- Intrinsic excitability: The ability of a neuron to generate action potentials in the absence of synaptic inputs, determined by its intrinsic membrane properties and ion channel composition.

- Synaptic excitability: The ability of a neuron to generate action potentials in response to synaptic inputs from other neurons.

Ion Channels in Neuronal Excitability

Ion channels play a crucial role in regulating neuronal excitability by controlling ion flow across the neuronal membrane, influencing membrane potential and action potential generation [1]. Their opening and closing are regulated by voltage, ligands, and neuromodulators.

Table: Major Ion Channel Types and Their Functions in Neuronal Excitability

| Ion Channel Type | Function in Neuronal Excitability |

|---|---|

| Voltage-gated sodium channels | Generate and propagate action potentials |

| Voltage-gated potassium channels | Repolarize the membrane after action potentials |

| Voltage-gated calcium channels | Regulate neurotransmitter release |

| Ligand-gated ion channels | Mediate synaptic transmission |

Key Research Reagent Solutions

Essential materials and reagents for studying neuronal excitability include:

Table: Essential Research Reagents for Neuronal Excitability Studies

| Reagent/Material | Function/Application |

|---|---|

| Acute brain slice preparation solutions | Maintain neuronal viability during slice preparation and recording [2] |

| Whole-cell patch clamp solutions | Intracellular and extracellular solutions for patch clamp recordings [2] |

| Enzymes for tissue dissociation (e.g., proteases) | Dissociate neuronal tissue for single-cell recordings |

| Ion channel modulators (agonists/antagonists) | Investigate specific ion channel contributions to excitability |

| Fluorescent indicators (e.g., voltage-sensitive dyes) | Visualize neuronal activity and membrane potential changes |

| Mechanosensitive compounds | Study mechanosensitive properties in chordotonal neurons [3] |

Electrophysiology Protocols for Assessing Neuronal Excitability

Acute Brain Slice Preparation for Electrophysiology

This protocol describes preparing live brain slices for extracellular and intracellular electrophysiology recordings [2].

Materials:

- Artificial cerebrospinal fluid (ACSF)

- Sucrose-based cutting solution

- Vibratome or tissue slicer

- Oxygenation system (95% O₂, 5% CO₂)

- Recording chamber with temperature control

Procedure:

- Rapidly extract brain tissue following approved institutional guidelines.

- Dissect region of interest and glue to vibratome stage.

- Prepare 300-400 μm thick slices in ice-cold, oxygenated cutting solution.

- Incubate slices in oxygenated ACSF at 32-34°C for 30 minutes.

- Maintain slices at room temperature for at least 1 hour before recording.

- Transfer individual slices to recording chamber perfused with oxygenated ACSF at 28-32°C.

Whole-Cell Patch Clamp Recording of Pyramidal Neurons

This protocol enables assessment of neuronal excitability and synaptic function in identified cell types [2].

Materials:

- Patch pipettes (3-6 MΩ resistance)

- Intracellular pipette solution

- Oxygenated extracellular solution

- Vibration isolation table

- Faraday cage

- Amplifier with data acquisition system

Procedure:

- Pull borosilicate glass capillaries to appropriate tip diameter.

- Fill pipettes with filtered intracellular solution.

- Position pipette near target neuron using micromanipulators.

- Apply gentle positive pressure while advancing pipette.

- Form gigaseal (>1 GΩ) by applying gentle suction.

- Compensate pipette capacitance and rupture membrane with additional suction or voltage pulses.

- Record in current-clamp or voltage-clamp mode based on experimental needs.

- For excitability assessment, inject current steps (e.g., -100 to +300 pA in 10-20 pA increments).

- Analyze resting membrane potential, input resistance, and action potential properties.

Extracellular Recording of Compound Action Potentials (CAPs)

This protocol measures synchronized electrical activity from multiple neurons [2].

Materials:

- Extracellular recording electrodes

- Stimulating electrodes

- Oxygenated extracellular solution

- Data acquisition system with stimulator

Procedure:

- Position stimulating and recording electrodes in region of interest.

- Deliver electrical stimuli of varying intensities (0.1-10 mA, 0.1-1 ms duration).

- Record evoked responses at 10-50 kHz sampling rate.

- Analyze CAP amplitude, latency, and conduction velocity.

- For long-term potentiation studies, apply high-frequency stimulation (e.g., 100 Hz for 1 second).

Extracellular Recordings of Mechanically Stimulated Neurons

This protocol, adapted from Drosophila studies, records neuronal activity from mechanically stimulated sensory neurons [3].

Materials:

- Dissection tools for fine tissue preparation

- Extracellular recording setup for small specimens

- Mechanical stimulation apparatus

- Vibration damping system

Procedure:

- Dissect larvae in appropriate physiological solution.

- Identify and access pentascolopidial chordotonal organs (lch5).

- Position recording electrode on lch5 neurons.

- Apply controlled mechanical stimulation while recording.

- Quantify action currents and response properties.

Emerging Technologies and Future Directions

Quantum Computing in Neural Excitability Modeling

Emerging approaches are exploring quantum computing to model ion channels and action potentials, leveraging the inherently quantum mechanical properties of ion movement at atomic scales [4]. Quantum algorithms show potential for revolutionizing simulations of ion channel behavior and neuronal signaling, though practical challenges including qubit coherence, error rates, and hardware scalability remain [4].

The BRAIN Initiative and Neural Circuit Analysis

Large-scale initiatives are prioritizing the analysis of neural circuits, requiring identification and characterization of component cells, definition of synaptic connections, observation of dynamic activity patterns during behavior, and perturbation testing [5]. This integrated approach spans spatial and temporal scales to understand how dynamic neural activity patterns transform into cognition, emotion, perception, and action [5].

Experimental Workflows and Signaling Pathways

The Critical Role of Ion Channels in Regulating Neuronal Activity

Ion channels are transmembrane protein pores that facilitate the selective flow of ions such as sodium (Na⁺), potassium (K⁺), calcium (Ca²⁺), and chloride (Cl⁻) across cellular membranes [6]. These channels are fundamental to electrical signaling throughout the nervous system, controlling processes ranging from fundamental neuronal communication to complex cognitive functions. In recent years, advanced techniques including single-cell transcriptomics, biophysical modeling, and high-throughput screening have dramatically enhanced our understanding of how diverse ion channel genes dictate neuronal physiology and enable the rich diversity of neuronal behaviors observed in the brain [7] [8]. This document provides detailed application notes and experimental protocols for studying ion channel function within the context of modern electrophysiology research, with particular emphasis on bridging molecular genetics with physiological outcomes.

Ion Channel Diversity and Neuronal Excitability

The brain contains an extraordinary diversity of neuronal cell types, each exhibiting distinct genetic signatures and functional properties [7]. This physiological diversity stems largely from the specific composition and density of ion channels expressed in the neuronal membrane. Voltage-gated ion channels (VGICs), including those for Na⁺, K⁺, and Ca²⁺, are critical regulators of membrane potential and cellular excitability, making them important drug targets for neurological, cardiovascular, and immunological diseases [9].

Table 1: Major Voltage-Gated Ion Channel Families and Their Neuronal Functions

| Ion Channel Family | Primary Ions | Activation Mechanism | Key Physiological Roles in Neurons | Associated Channelopathies |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Voltage-Gated Sodium (Naᵥ) Channels | Na⁺ | Voltage-dependent | Action potential initiation and propagation | Epilepsy, chronic pain, neuropathies |

| Voltage-Gated Potassium (Kᵥ) Channels | K⁺ | Voltage-dependent | Action potential repolarization, firing frequency modulation | Episodic ataxia, epilepsy |

| Voltage-Gated Calcium (Caᵥ) Channels | Ca²⁺ | Voltage-dependent | Neurotransmitter release, synaptic plasticity, gene expression | Migraine, cerebellar ataxia |

| Transient Receptor Potential (TRP) Channels | Na⁺, K⁺, Ca²⁺ | Multiple (chemical, thermal, mechanical) | Pain sensation, sensory transduction, cellular signaling | Neurodegeneration, pain disorders |

Different neuronal cell types express characteristic combinations of these channels, which shape their distinctive firing patterns. For example, fast-spiking parvalbumin (Pvalb)-positive interneurons exhibit high densities of certain potassium channels (specifically, a high maximal conductance of the delayed rectifier K⁺ current, gKd), which enables their rapid spiking capability and supports high-frequency signaling in neuronal networks [8]. In contrast, pyramidal neurons display different ionic conductances that result in broader action potentials and lower maximum firing rates. Understanding these relationships is crucial for deciphering the functional building blocks of neural circuits.

Experimental Protocols for Ion Channel and Neuronal Characterization

Protocol 1: Patch-seq for Multimodal Neuronal Profiling

The Patch-seq technique allows for the integration of electrophysiological recordings, single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq), and morphological reconstruction from the same individual neuron [8]. This protocol enables the direct investigation of how a neuron's gene expression relates to its functional and structural properties.

Workflow Diagram for Patch-seq Analysis:

Detailed Methodology:

- Tissue Preparation: Prepare acute brain slices (300-350 μm thickness) from the region of interest (e.g., mouse motor cortex) using a vibrating tissue slicer. Maintain slices in oxygenated (95% O₂/5% CO₂) artificial cerebrospinal fluid (aCSF) at approximately 30°C for 1-5 hours before recording [8] [10].

- Electrophysiological Recording: Transfer a slice to the recording chamber and identify neurons using differential interference contrast (DIC) optics. Perform whole-cell patch-clamp recordings using pipettes with a resistance of 2.5-4 MΩ.

- Intracellular Solution (example): potassium gluconate (130 mM), KCl (10 mM), HEPES (10 mM), MgATP (4 mM), NaGTP (0.3 mM), phosphocreatine (10 mM) [10].

- Record neuronal responses to a series of current injections to characterize intrinsic excitability, including action potential properties and firing patterns.

- Cellular Content Harvesting: Upon completion of electrophysiological recording, gently aspirate the cytoplasmic content into the patch pipette by applying negative pressure. Expel the contents into a collection tube for subsequent RNA sequencing [8].

- Library Preparation and Sequencing: Convert the harvested RNA into a sequencing library using a single-cell RNA-seq platform (e.g., SMART-seq2 for higher sensitivity). Sequence the libraries to obtain full-transcriptome data from the recorded cell.

- Data Analysis and Integration:

- Electrophysiology Analysis: Calculate standard electrophysiological features (e.g., resting membrane potential, input resistance, spike amplitude, adaptation index) from the recorded traces.

- Transcriptomics Analysis: Process sequencing data to quantify gene expression levels, focusing on ion channel genes and neuronal markers.

- Multimodal Integration: Use statistical models, such as sparse reduced-rank regression (sRRR), to identify correlations between the expression levels of specific ion channel genes and the electrophysiological properties of the neuron [7] [8].

Protocol 2: Recursive Piecewise Data Assimilation (RPDA) for Ionic Current Estimation

Recursive Piecewise Data Assimilation (RPDA) is a computational method that infers the underlying ionic current waveforms and channel properties from current-clamp recordings [10]. Its strength lies in its ability to simultaneously estimate all major ionic currents in a neuron from a small set of high-quality electrophysiological data.

Workflow Diagram for RPDA Analysis:

Detailed Methodology:

Informative Stimulation Protocol Design:

- A key prerequisite for RPDA is using a current stimulation protocol that is sufficiently informative to constrain all model parameters [10].

- The protocol should probe neuron dynamics across different states: depolarized (eliciting action potentials), sub-threshold (near resting potential), and hyperpolarized.

- Incorporate a mix of positive/negative current pulses and complex oscillations (e.g., chaotic signals from the Lorenz system) to cover a wide range of time constants (e.g., 0.1 ms to 500 ms) relevant to neuronal ion channels [10].

- Example: A protocol combining square pulses with a chaotic signal generated by the Lorenz system (σ=10, β=8/3, ρ=28) [10].

Electrophysiological Recording:

- Perform whole-cell current-clamp recordings as described in Protocol 3.1, using the optimized stimulation protocol.

- Synaptic transmission should be pharmacologically inhibited (e.g., using kynurenate, picrotoxin, and strychnine) to isolate intrinsic neuronal properties [10].

Data Assimilation and Parameter Estimation:

- The voltage time series data (

V(t)) is assimilated into a Hodgkin-Huxley-type model of the neuron. - The RPDA algorithm works by recursively synchronizing the model equations to the observed voltage trace over short, sequential time windows.

- It adjusts model parameters (ionic conductances, activation thresholds, gate time constants) to minimize the difference between the model output and the experimental data.

- This process yields estimates of the unobserved state variables, including the gating parameters and the time-course of individual ionic currents (e.g., sodium, potassium, calcium) [10].

- The voltage time series data (

Validation and Application:

- The method can be experimentally validated by applying known ion channel blockers and confirming that RPDA correctly identifies the change in the targeted current.

- RPDA can quantify compensatory changes in non-targeted ion channels, demonstrating its utility as a drug toxicity counter-screen [10].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Reagents and Tools for Neuronal Ion Channel Research

| Tool / Reagent | Category | Primary Function | Example Application |

|---|---|---|---|

| Patch-seq Platform | Integrated Methodology | Concurrently profiles transcriptome and physiology from single neurons | Linking ion channel gene expression to electrophysiological phenotypes [8] |

| Automated Patch Clamp (APC) | Instrumentation | High-throughput electrophysiology screening | Drug discovery campaigns on recombinant ion channels (e.g., hNaV1.7) [11] |

| Planar Lipid Bilayer System | Instrumentation | Functional characterization of purified ion channels in a defined membrane environment | Studying gating and permeation properties unbiased by cellular components [12] |

| Protein Language Models (e.g., ESM-2) | Computational Tool | Predicts functional effects of missense variants on ion channel function | Classifying variants as gain-of-function (GOF) or loss-of-function (LOF) [13] |

| Fluorescent Indicators (e.g., from ION Biosciences) | Chemical Reagent | Optical measurement of ion dynamics and membrane potential | High-throughput assay development and screening services [14] |

| Cryo-Electron Microscopy (Cryo-EM) | Structural Tool | High-resolution structure determination of ion channels in near-native states | Investigating ion channel regulation by lipids and chaperones [6] |

Data Analysis and Interpretation

Linking Gene Expression to Biophysical Parameters

Advanced computational approaches are required to move beyond correlations and establish mechanistic links between transcriptomic data and electrophysiological properties. One powerful method involves using conductance-based models as an intermediate layer [7] [8].

- Procedure: First, fit a Hodgkin-Huxley (HH)-based model with interpretable parameters (e.g., maximal ionic conductances) to the electrophysiological recording of a neuron. Then, use a statistical model (e.g., sparse linear regression or a neural network) to predict these best-fitting HH-model parameters from the cell's gene expression profile [7] [8].

- Outcome: This creates an interpretable, two-step mapping from genes to function. For example, this approach has revealed mechanistically plausible links, such as the association of the

Kcnc1gene with potassium channel conductance (gKv3.1) and theCacna2d1gene with calcium channel conductance [8].

Functional Prediction of Genetic Variants

Accurately classifying the functional impact of ion channel variants is critical for diagnosing channelopathies. Protein language models (pLMs) like Evolutionary Scale Modeling (ESM) offer a significant advance.

- Procedure: The "MissION" classifier uses pLM embeddings (latent representations of amino acid sequences) to predict whether a missense variant will cause GOF or LOF [13].

- Implementation: The model is trained on thousands of variants with known functional consequences. It processes the sequence embedding of the variant, cropped to a window around the substitution site, through a neural network classifier [13].

- Performance: This approach achieves high predictive performance (ROC-AUC: 0.925), generalizing well even to ion channel genes with little available experimental data [13].

Ion channels are the fundamental regulators of neuronal excitability, and modern research tools now allow us to dissect their roles with unprecedented precision. The integration of advanced electrophysiology, single-cell genomics, and sophisticated computational models is bridging the long-standing gap between neuronal gene expression and physiological function. The protocols and applications detailed here—from the multimodal Patch-seq and powerful RPDA analysis to the predictive power of protein language models—provide a roadmap for researchers to deepen the mechanistic understanding of neuronal diversity, disease-associated channelopathies, and accelerate the development of targeted therapeutics for neurological disorders.

Electrophysiology provides the foundational framework for understanding neuronal excitability and communication. The core principles of resting membrane potential, action potentials, and synaptic transmission form the essential trilogy that enables the nervous system to process and transmit information. For researchers measuring neuronal activity, a precise understanding of these concepts is paramount for designing experiments, interpreting data, and developing novel therapeutic agents. These electrical events are not merely isolated phenomena but are intricately linked processes that convert chemical gradients into electrical signals and back into chemical messengers, allowing for the complex computation that underpins all nervous system function [15] [16] [17].

This article details these core concepts with a specific focus on their relevance to experimental protocols in neuronal research. We synthesize classic physiological understanding with contemporary research findings, such as a recent study revealing the role of extracellular phosphorylation in synaptic plasticity, thereby updating the textbook model of synaptic function [18].

Resting Membrane Potential: The Foundation of Excitability

The resting membrane potential (RMP) is the stable, electrical potential difference across the plasma membrane of a non-excited cell, typically measured at -70 mV in neurons relative to the extracellular environment. This negative interior is the baseline from which all electrical activity arises [16] [19].

Biophysical Basis and Ion Dynamics

The RMP is generated and maintained by the interplay of ionic concentration gradients and selective membrane permeability. The key ions involved are potassium (K+), sodium (Na+), and chloride (Cl-), alongside impermeant intracellular anions (e.g., proteins) [20].

Table 1: Ionic Concentrations and Equilibrium Potentials in a Typical Mammalian Neuron

| Ion | Intracellular Concentration | Extracellular Concentration | Equilibrium Potential (Eion) | Primary Role in RMP |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Potassium (K+) | 120-130 mM | 4-5 mM | -90 mV | Dominant influence; high permeability at rest pulls potential toward EK |

| Sodium (Na+) | 14-15 mM | 140-145 mM | +60 to +65 mV | Minor influence; low permeability at rest slightly depolarizes the cell |

| Chloride (Cl-) | 5-10 mM | 110-120 mM | -65 to -70 mV | Stabilizes potential near rest; permeability varies by cell type |

The Nernst equation is used to calculate the equilibrium potential for a single ion, the point at which its concentration gradient is exactly balanced by the electrical gradient [16] [20]:

E_ion = (RT/zF) * ln([ion]_outside / [ion]_inside)

Where R is the gas constant, T is temperature, z is the ion's valence, and F is Faraday's constant. At body temperature (37°C) for a monovalent cation, this simplifies to E_ion ≈ 61.5 * log([out]/[in]).

Since the membrane is permeable to multiple ions simultaneously, the Goldman-Hodgkin-Katz (GHK) voltage equation provides a more accurate prediction of the RMP by incorporating the relative permeabilities (P) of the major ions [16] [19]:

V_m = (RT/F) * ln( (P_K[K+]_out + P_Na[Na+]_out + P_Cl[Cl-]_in) / (P_K[K+]_in + P_Na[Na+]_in + P_Cl[Cl-]_out) )

Because the membrane at rest is approximately 20-100 times more permeable to K+ than to Na+, the RMP is close to, but slightly more positive than, EK [19].

The Role of the Sodium-Potassium Pump

The Na+/K+ ATPase pump is critical for maintaining the long-term stability of the RMP. This electrogenic pump actively transports 3 Na+ ions out of the cell and 2 K+ ions in for every molecule of ATP hydrolyzed, thereby directly contributing a small hyperpolarizing current and, more importantly, constantly maintaining the concentration gradients that K+ leaks down [16] [20] [19].

Diagram 1: Ion dynamics generating the resting membrane potential.

Action Potential: The Electrical Signal

An action potential (AP) is a rapid, all-or-nothing, self-regenerating wave of depolarization that travels along the axon, serving as the fundamental unit of neuronal communication [15] [21]. Its stereotypical shape is consistent within a given cell type but can vary in duration between cell types, from less than a millisecond in fast-spiking neurons to over 100 milliseconds in cells dominated by voltage-gated calcium channels [15].

Phases and Ion Channels

The initiation and propagation of an AP can be dissected into distinct phases driven by the sequential activation and inactivation of voltage-gated ion channels.

Table 2: Phases of the Neuronal Action Potential and Underlying Mechanisms

| Phase | Membrane Potential | Key Permeability Change | Ionic Flow | Governing Mechanism |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Resting State | -70 mV | PK+ >> PNa+ | K+ leak outward > Na+ leak inward | Membrane at RMP; voltage-gated Na+ and K+ channels closed. |

| 2. Depolarization to Threshold | Rising to ~ -55 mV | Stimulus-gated or synaptic Na+ channels open. | Net inward Na+ current. | Sufficient depolarization opens enough voltage-gated Na+ channels to reach the threshold for positive feedback. |

| 3. Rapid Depolarization (Rising Phase) | Rapid rise to +30 to +40 mV | P_Na+ increases dramatically. | Massive, rapid Na+ influx. | Voltage-gated Na+ channels activate (open) rapidly, driving Vm toward ENa. |

| 4. Repolarization (Falling Phase) | Falls back toward RMP | PNa+ inactivates; PK+ increases. | Na+ influx stops; K+ efflux increases. | Na+ channels inactivate; delayed voltage-gated K+ channels open, driving Vm back toward EK. |

| 5. After-Hyperpolarization | Briefly more negative than RMP (e.g., -80 mV) | P_K+ remains elevated. | Continued K+ efflux. | Delayed K+ channels close slowly; Na+ channels reset from inactivation. |

| 6. Refractory Period | Returns to RMP | P_Na+ is inactivated. | Ionic gradients restored by pumps. | Absolute refractory period: No new AP can be initiated. Relative refractory period: A stronger-than-normal stimulus is required. |

The Hodgkin-Huxley Model and All-or-Nothing Principle

The biophysical properties of the AP are classically described by the Hodgkin-Huxley model, a set of differential equations that quantify the conductance changes of voltage-gated Na+ and K+ channels [15]. A critical feature of the AP is its all-or-nothing nature. Once the membrane potential at the axon initial segment reaches the threshold (typically -55 mV), the positive feedback cycle of Na+ channel activation proceeds explosively and independently of the initial stimulus strength [21]. This ensures the faithful, non-decremental propagation of the signal along the axon.

Propagation and Saltatory Conduction

APs propagate along the axon because the depolarizing current from the active region depolarizes adjacent membrane segments to threshold. In myelinated axons, the process of saltatory conduction significantly increases speed and metabolic efficiency. The myelin sheath, formed by oligodendrocytes or Schwann cells, insulates the axon. APs actively regenerate only at the unmyelinated Nodes of Ranvier, "jumping" from node to node [21].

Diagram 2: Action potential initiation decision tree.

Synaptic Transmission: Bridging the Gap

Synaptic transmission is the process by which an AP in a presynaptic neuron is converted into an electrical or biochemical signal in a postsynaptic cell. This occurs at specialized junctions called synapses, most commonly via the release of chemical neurotransmitters [17].

The Synaptic Vesicle Cycle

The core mechanism of neurotransmitter release is the Ca2+-dependent synaptic vesicle cycle [17] [22]:

- Docking and Priming: Synaptic vesicles loaded with neurotransmitter are docked at the presynaptic active zone and molecularly "primed" for release by proteins including SNARE complexes (syntaxin-1, SNAP-25, synaptobrevin-2) and Munc13 [17] [22].

- Calcium Influx and Fusion: An arriving AP depolarizes the presynaptic terminal, opening voltage-gated calcium channels (VGCCs). The rapid influx of Ca2+ triggers a conformational change in the calcium sensor protein synaptotagmin, leading to the fusion of the vesicle membrane with the presynaptic membrane and exocytosis of neurotransmitter into the synaptic cleft.

- Recycling: The vesicle membrane is retrieved via endocytosis and refilled with neurotransmitter for future rounds of release.

Postsynaptic Receptors and Potentials

Released neurotransmitters bind to ligand-gated ion channels (ionotropic receptors) or G-protein coupled receptors (metabotropic receptors) on the postsynaptic membrane.

- Ionotropic Receptors mediate fast synaptic transmission. For example, glutamate binding to AMPA-type receptors opens cation channels, leading to Na+ influx and excitatory postsynaptic potentials (EPSPs), which depolarize the neuron. Conversely, GABA binding to GABAA receptors opens Cl- channels, leading to inhibitory postsynaptic potentials (IPSPs), which hyperpolarize or shunt excitation [17].

- Metabotropic Receptors act through second messenger systems to produce slower, longer-lasting, and more modulatory effects on neuronal excitability and synaptic strength [17].

Emerging Mechanism: Extracellular Phosphorylation in Synaptic Plasticity

Recent research has unveiled a novel layer of regulation in synaptic transmission: extracellular phosphorylation within the synaptic cleft. A 2025 study identified that the ectokinase Vertebrate Lonesome Kinase (VLK) is secreted by presynaptic neurons following injury [18]. VLK then phosphorylates the extracellular domain of Ephrin type-B receptor 2 (EphB2) on the postsynaptic membrane. This phosphorylation event promotes the clustering of NMDA receptors with EphB2 receptors, a key mechanism for strengthening synaptic connections and mediating injury-induced pain hypersensitivity [18]. This discovery updates the traditional model of the synapse by showing that kinase activity within the cleft itself is a critical regulator of receptor function and synaptic plasticity.

Diagram 3: Synaptic transmission with the novel VLK pathway.

Experimental Protocols for Electrophysiological Investigation

Protocol: Extracellular Recording of Mechanically Stimulated Neurons

This protocol, adapted from recent methodology, is designed for recording action currents (the extracellular correlate of APs) from sensory neurons in Drosophila larvae, useful for studying mechanotransduction [3].

Application: Investigating the molecular mechanisms of mechanosensation, auditory transduction, and the function of specific ion channels in a genetically tractable model system.

Key Steps:

- Dissection: Isolate the intact nervous system of the Drosophila larva in a physiological saline solution to maintain tissue viability.

- Stimulation and Recording: Position an extracellular recording electrode (e.g., sharp glass microelectrode or suction electrode) near the cell body or axon of the target chordotonal neuron (lch5). Apply controlled mechanical stretch to the neuron using a micromanipulator.

- Signal Acquisition: Record the resulting electrical activity (action currents) using a standard extracellular amplifier. Signals are typically band-pass filtered (e.g., 300 Hz to 3 kHz) to isolate spiking activity.

- Data Analysis: Quantify neuronal activity by measuring parameters such as firing rate, latency to first spike, and spike adaptation in response to the mechanical stimulus. Compare these metrics across genetic manipulations or pharmacological treatments.

Protocol: Investigating Synaptic Plasticity via the VLK Pathway

Based on the recent discovery of VLK's role [18], this protocol outlines a methodology to probe this novel signaling pathway in a pain research context.

Application: Elucidating mechanisms of synaptic strengthening in pain pathways, learning, and memory; screening for potential analgesic drugs targeting VLK or EphB2.

Key Steps:

- Preparation: Utilize ex vivo spinal cord slices or primary cultures of sensory neurons co-cultured with spinal cord neurons. Alternatively, use human sensory neuron cultures for translational impact.

- Genetic/Pharmacological Manipulation:

- Knockdown/Knockout: Use transgenic mice or viral vectors to delete or silence the Vlk gene specifically in sensory neurons.

- Inhibition: Apply a selective VLK inhibitor to the synaptic preparation.

- Activation: Apply recombinant VLK protein to normal tissue.

- Stimulation and Measurement:

- Induce synaptic plasticity using electrical stimulation protocols (e.g., high-frequency stimulation) or chemical LTP induction.

- Measure postsynaptic potentials using whole-cell patch-clamp electrophysiology in the postsynaptic neuron.

- Quantify NMDA receptor clustering via immunohistochemistry (e.g., anti-NMDAR and anti-EphB2 antibodies) and super-resolution microscopy.

- Behavioral Correlation (in vivo): In parallel mouse experiments, assess pain hypersensitivity (e.g., using von Frey filaments for mechanical allodynia) following injury in control vs. VLK-deficient animals.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents and Tools for Electrophysiology and Synaptic Research

| Reagent / Tool | Function / Application | Specific Examples / Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Patch-Clamp Amplifiers (Axon Instruments) | High-fidelity recording of transmembrane currents (whole-cell, single-channel) and membrane potential. | Essential for quantifying AP properties, postsynaptic currents, and ion channel kinetics. [23] |

| Tetrodotoxin (TTX) | Selective blocker of voltage-gated sodium channels. | Used to isolate Na+ current contributions or silence neuronal firing. |

| Tetraethylammonium (TEA) | Broad-spectrum blocker of voltage-gated potassium channels. | Used to isolate K+ current contributions and prolong the AP duration. |

| Selective Kinase Inhibitors | Pharmacological disruption of specific signaling pathways. | Emerging tools for novel targets like VLK inhibitors to probe synaptic plasticity and pain mechanisms. [18] |

| Recombinant Proteins (e.g., VLK) | To directly activate or supplement a specific pathway. | Application of recombinant VLK is sufficient to induce pain hypersensitivity and NMDA receptor clustering in studies. [18] |

| SNARE Complex Modifiers (e.g., Botulinum Toxin) | Proteolytic cleavage of SNARE proteins to inhibit vesicle fusion. | Used to dissect the fundamental mechanisms of neurotransmitter release. [17] |

| Agonists/Antagonists for Neurotransmitter Receptors (e.g., CNQX, AP5, Bicuculline) | To selectively activate or block specific ionotropic or metabotropic receptors. | Critical for determining the receptor subtypes mediating synaptic responses. [17] |

| Caged Compounds (e.g., Caged Glutamate, Caged Ca2+) | Precursors of bioactive molecules that are activated by UV light. | Allows for precise spatial and temporal control of neurotransmitter application or intracellular signaling. |

Electrophysiology is the field of research studying current or voltage changes across a cell membrane, and it is a fundamental tool for investigating neuronal activity [24]. Neurons communicate via action potentials—rapid electrical signals that travel along axons and trigger the release of neurotransmitters across synapses [25]. When neurotransmitters bind to receptors, they enable the flow of ions (such as Na+ or K+) across membrane channels, changing the neuron's membrane potential [25]. Measuring these minute electrical signals requires a suite of highly specialized equipment capable of extreme precision, low noise, and stable mechanical operation. The core instruments of any electrophysiology lab include microscopes for visualization, amplifiers for signal detection, micropipette pullers for electrode fabrication, and Faraday cages for noise shielding [24]. This application note details the function, key specifications, and experimental protocols for these essential tools, providing a framework for reliable measurement of neuronal activity in research and drug development.

The Core Electrophysiology Setup

An electrophysiology setup is an integrated system where each component plays a critical role in obtaining high-quality measurements of neuronal function. The four main laboratory requirements are: (1) a controlled Environment to keep the biological preparation healthy; (2) Optics for visualizing the preparation; (3) Mechanics for stably positioning the microelectrode; and (4) Electronics for amplifying and recording the signal [24]. A standard rig consists of a microscope with a micromanipulator, an amplifier, a digitizer, and a computer with acquisition software, all housed on an anti-vibration table within a Faraday cage to shield from external interference [24]. The following sections break down the key components in detail.

Detailed Equipment Analysis

Table 1: Key Equipment for Neuronal Electrophysiology

| Equipment Category | Primary Function | Key Specifications | Considerations for Researchers |

|---|---|---|---|

| Microscope with Micromanipulator | Optical magnification and precise electrode positioning | • 300-400x magnification• Contrast enhancement (DIC, Phase, Hoffman)• Nanometer-precision 3D movement | An inverted microscope is preferable for easier electrode access from above [24]. |

| Amplifier | Measures electrical currents or changes in membrane potential | • Low-noise performance• Variable gain control• Capable of voltage-clamp and current-clamp | Amplifies signals from the headstage; some models allow customization of gain and filter settings [24] [26]. |

| Micropipette Puller | Fabricates glass microelectrodes for recording | • Programmable heat, force, and pull parameters• Multiple pull stages for consistency | The type of glass, ambient temperature, and humidity all affect the final pipette shape [27]. |

| Faraday Cage | Enclosure to block external electromagnetic interference | • Wire mesh or solid conductive material• Grounded to dissipate currents | Essential for low-current measurements (e.g., below 1 µA); must be properly grounded to the instrument [24] [28]. |

| Digitizer | Converts analog signals from the amplifier into digital data | • High sampling rate (e.g., 500 kHz)• Features for noise reduction (e.g., HumSilencer) | Positioned between the amplifier and computer; determines the quality of the signal for analysis [24]. |

| Headstage | Holds the micropipette and transmits electrical signals to the amplifier | • Critical electric circuitry to reduce noise• Specifically tuned for the amplifier | The headstage is mounted onto the micromanipulator, which controls its position [24]. |

Research Reagent Solutions

The following table lists essential materials and reagents required for a typical electrophysiology experiment, such as at the C. elegans neuromuscular junction [29].

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

| Item | Function/Application | Example Specifications |

|---|---|---|

| Borosilicate Glass Capillaries | Used to fabricate recording, stimulus, and cutting pipettes. | Outer diameter: 1.0 - 1.5 mm; Inner diameter: 1.1 mm [29] [30]. |

| Internal Pipette Solution | Fills the recording pipette to establish electrical continuity with the cell interior. | Contains ions (e.g., CsCl, CsF), pH buffered to 7.2 with CsOH [29]. |

| Extracellular Solution | Maintains the biological preparation in a healthy, physiological state during recording. | Bubbled with 5% CO₂ and 95% O₂; contains salts (NaCl, KCl, CaCl₂, MgCl₂, glucose) [29]. |

| Collagenase Solution | Enzyme used to assist in the dissection and preparation of tissue. | 1 mg/mL stock solution in extracellular solution [29]. |

| Sylgard 184 | An elastomer used to coat pipettes, decreasing capacitance and improving noise characteristics. | Cured overnight at 60°C [29] [30]. |

| Histoacryl Blue Tissue Adhesive | Used to immobilize the dissected preparation for stable recording. | A blue-colored surgical glue for easy visualization during dissection [29]. |

Experimental Protocols

Workflow for Electrophysiological Recording and Correlation Microscopy

The following diagram outlines a comprehensive protocol that integrates electrophysiological recording with subsequent electron microscopy analysis, enabling researchers to correlate neuronal function with ultrastructural anatomy [29] [31].

Protocol: Pipette Pulling and Preparation

The creation of high-quality glass microelectrodes is a critical first step for successful electrophysiology. The process is both a science and an art, requiring an understanding of material properties and puller mechanics [27].

Detailed Steps for Pipette Preparation:

Pulling Pipettes:

- Capillary Selection: Use clean, dust-free borosilicate glass capillaries. For standard patch-clamp recording, capillaries with an outer diameter of 1.0 mm to 1.5 mm are typical [30].

- Program Design: Use a programmable puller (e.g., Sutter P-97) with a multi-step program. A common approach is a 4-5 step program with descending heat and velocity at each step, and a small pull on the final step [30].

- Parameter Adjustment: The final pipette geometry is fine-tuned by adjusting key parameters [27]:

- Increase Heat: Results in a longer taper.

- Increase Force: Produces smaller tips and a longer taper.

- Increase Pull Distance: Yields smaller tips.

- Environmental Control: Note that room temperature and humidity can affect pull consistency and must be kept stable [27].

Pipette Finishing (Optional but Recommended):

- Coating: Coat the pipette shank with an insulator like Sylgard 184 or dental wax to decrease electrical capacitance and improve noise characteristics [30]. Apply air pressure to the back of the pipette during dipping to prevent the insulator from entering the tip.

- Fire Polishing: Use a microforge with a heated filament to smooth the pipette tip. A brief heat pulse of 1-2 seconds is sufficient to smooth the glass and remove any insulator from the tip opening [30].

Quality Control and Storage:

Protocol: In Vivo Electrophysiology at the Neuromuscular Junction

This protocol details the steps for performing electrophysiological recordings at the C. elegans neuromuscular junction (NMJ), a common model system [29].

Timing: Approximately 3 hours for preparation and recording.

Steps:

Preparation (Day Before Recording):

- Transfer 20-30 well-fed L4-stage worms to a new NGM plate for use the next day [29].

- Prepare, aliquot, and freeze the internal pipette stock solution. Adjust the pH to 7.2 before freezing [29].

- Prepare and freeze aliquots of collagenase digestion solution (1 mg/mL in extracellular solution) [29].

- Prepare Sylgard 184-coated circular coverslips and cure them overnight at 60°C [29].

Preparation (Day of Recording):

- Make 500 mL of fresh extracellular solution and bubble continuously with a mixture of 5% CO₂ and 95% O₂ for at least 20 minutes [29].

- Prepare an ice bottle to immobilize worms.

- Pull all required pipettes: recording pipettes (which must be polished), stimulus pipettes, and sharp cutting pipettes [29].

- Thaw one aliquot each of collagenase and internal pipette solution [29].

Dissection and Recording:

- Immobilization: Place worms on an agarose pad on a Sylgard-coated coverslip and cool on ice to immobilize them [29].

- Gluing and Dissection: Glue the worms to the coverslip using Histoacryl Blue tissue adhesive. Perform a longitudinal cut along the body wall using a sharp pipette to expose the neuromuscular junctions [29].

- Establishing Recording: Place the dissected preparation into the recording chamber, continuously perfused with oxygenated extracellular solution. Under visual guidance using the microscope, maneuver the recording pipette (filled with internal solution) onto a muscle cell using the micromanipulator. Apply gentle suction to form a tight seal (giga-ohm seal) [29].

- Data Acquisition: Use the amplifier and software to record postsynaptic currents. Signals are acquired through the headstage, amplified, digitized, and stored on a computer for subsequent analysis [29] [24].

Technical Considerations and Troubleshooting

The Science of Pulling Micropipettes

Creating consistent and high-quality micropipettes is foundational. Several factors influence the process [27]:

- Heat Transfer: The primary heat source is radiation from the filament. The distance between the glass and filament is critical for even heating. Convection from ambient air and conduction to filament holders also affect the glass transition and must be managed by allowing cool-down time between pulls [27].

- Filament Aging: The platinum/iridium filament slowly oxidizes with use, changing its heating properties over time and eventually burning out, which necessitates replacement [27].

- Glass Type: Different types of glass capillaries have different softening points. Even different manufacturing lots of the same product can show slight variations, requiring fine-tuning of pulling programs [27].

Principles and Proper Use of a Faraday Cage

A Faraday cage is an enclosure made of conductive material or mesh that blocks external electromagnetic fields [32]. It works by redistributing electrical charges on its exterior, which cancels out the effect of the external field inside the enclosure [28]. For electrophysiologists, its proper use is non-negotiable for high-fidelity recordings.

- When to Use: A Faraday cage should be used whenever possible, but it is absolutely essential for experiments involving low currents (below 1 µA) or high frequencies. The small electrical currents measured during patch-clamp experiments (in the picoamp range) can be easily distorted by external noise sources like radio waves or mains power lines [24] [28].

- Critical Grounding: Simply placing equipment inside a cage is insufficient. The cage must be grounded to the instrument's ground reference. An ungrounded cage can act as an antenna, capacitively coupling noise into the electrodes. Most potentiostats/amplifiers require the cage to be earth grounded, though some floating-ground instruments are exceptions [28].

- Design and Integrity: The cage's effectiveness depends on the conductivity of the material and the size of any holes. openings should be smaller than 1/10th the wavelength of the noise to be blocked. Special attention must be paid to doors and lids to ensure good electrical continuity across the seams [28]. A common and effective DIY solution is a wood-frame cage covered with copper or aluminum mesh [28].

The precise measurement of neuronal activity hinges on the correct selection, operation, and integration of core electrophysiology equipment. Microscopes with micromanipulators enable the visualization and precise placement of electrodes. Amplifiers and digitizers are crucial for faithfully detecting and converting minuscule biological signals. The art and science of pulling micropipettes provide the essential interface with the neuron itself. Finally, the Faraday cage creates the quiet electronic environment necessary for these sensitive measurements. By following the detailed application notes and protocols outlined in this document, researchers and drug development professionals can establish a robust foundation for investigating the mechanisms of neuronal function, synaptic transmission, and the effects of pharmacological compounds with high accuracy and reliability.

Core Techniques and Their Transformative Applications in Research and Drug Discovery

Patch-clamp electrophysiology represents the gold standard technique for high-resolution recording of ionic currents across biological membranes, enabling the functional study of ion channels at the level of single molecules to entire cellular networks [33]. Since its initial development by Neher and Sakmann in 1976 and subsequent refinement to include whole-cell configuration by Hamill et al. in 1981, this technique has revolutionized neurophysiology and drug discovery research [34]. The method's unparalleled sensitivity allows researchers to observe the conformational changes that individual ion channel proteins undergo during gating, providing critical insights into neuronal excitability, synaptic transmission, and the mechanisms of neurological diseases [33] [35]. For drug development professionals, patch-clamp electrophysiology serves as an essential tool for screening compounds that modulate ion channel function, offering direct assessment of drug efficacy and kinetics. This article details the core configurations, experimental protocols, and technical considerations that establish patch-clamp recording as an indispensable methodology in neuroscience research and pharmaceutical development.

Technical Configurations and Their Applications

The patch-clamp technique encompasses several configurations, each tailored to address specific experimental questions by providing access to different levels of electrophysiological information.

Table 1: Comparison of Primary Patch-Clamp Configurations

| Configuration | Key Feature | Primary Applications | Typical Pipette Resistance | Signal Resolution |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cell-Attached | Intact cell; records single-channel currents from a membrane patch | Single-channel kinetics, ligand-gated or mechanosensitive channel activity [33] | 12-24 MΩ [33] | Single-channel currents (pA range) |

| Whole-Cell | Direct electrical access to cell interior; records macroscopic currents | Neuronal excitability, action potentials, synaptic currents [35] [34] | 3-6 MΩ [34] | Macroscopic currents (nA range) |

| Inside-Out | Isolated intracellular membrane face | Modulation of channels by intracellular messengers [34] | 5-10 MΩ | Single-channel currents |

| Outside-Out | Isolated extracellular membrane face | Rapid solution exchange studies of ligand-gated channels [34] | 5-10 MΩ | Single-channel currents |

Each configuration provides unique experimental advantages. The cell-attached mode permits long observation periods of single-channel activity in their native membrane environment without disrupting intracellular content, making it ideal for studying baseline channel kinetics [33]. Conversely, the whole-cell configuration allows comprehensive assessment of a neuron's integrative properties, including synaptic inputs and action potential generation, by providing electrical access to the entire cell [35]. The excised patch configurations (inside-out and outside-out) enable precise control of the solution environment on either side of the membrane, facilitating studies of channel modulation by second messengers or pharmaceuticals.

Experimental Protocols

Cell-Attached Single-Channel Recording

This protocol outlines the procedure for obtaining one-channel cell-attached recordings, optimized for NMDA receptors or mechanosensitive channels like PIEZO1 [33].

Materials and Equipment:

- Patch-clamp amplifier and data acquisition system (e.g., with QuB software)

- Vibration isolation table, Faraday cage

- Inverted microscope with phase-contrast and fluorescence capabilities

- Pipette puller and polisher

- Borosilicate glass capillaries

- HEK293 cells or cortical neurons expressing the channel of interest

Step-by-Step Procedure:

Cell Preparation: Maintain HEK293 cells (passages 22-40) in DMEM with 10% FBS and 1% penicillin/streptomycin. For transfection, plate cells at ~10⁵ cells/35 mm dish and transfect with appropriate channel cDNA (e.g., GluN1, GluN2A for NMDA receptors) using a calcium phosphate method. Use cells for recording 24-48 hours post-transfection [33].

Pipette Preparation: Pull borosilicate glass capillaries to produce tips with 1.4-1.6 μm outer diameter, yielding resistances of 12-24 MΩ when filled with pipette solution. Fire-polish to optimize seal formation [33].

Pipette Solution: For NMDA receptors, use a solution containing (in mM): 1 glutamate, 0.1 glycine, 150 NaCl, 2.5 KCl, 1 EDTA, and 10 HEPES (pH 8.0 with NaOH). This provides saturating agonist concentrations and physiologic permeant ions [33].

Seal Formation: Select a fluorescently identified, healthy cell. Apply slight positive pressure to the pipette while lowering it into the bath solution. Once the pipette contacts the cell membrane, release positive pressure and apply gentle negative pressure to achieve a giga-ohm seal (resistance >1 GΩ) [33].

Data Acquisition: Set the amplifier to voltage-clamp mode with applied voltage typically between +60 to +100 mV. Acquire data at 40 kHz sampling rate with a 10 kHz low-pass filter. Record continuous stretches of activity for kinetic analysis [33].

Whole-Cell Patch-Clamp Recording in Brain Slices

This protocol details the steps for whole-cell recording from neurons in acute brain slices, enabling assessment of neuronal excitability and synaptic function [35].

Materials and Equipment:

- Vibratome for slice preparation

- Carbogen (95% O₂/5% CO₂) delivery system

- aCSF and intracellular solutions

- Micromanipulator, amplifier, and data acquisition software

Step-by-Step Procedure:

Acute Slice Preparation: Prepare cutting solution containing (in mM): 220 glycerol, 2.5 KCl, 1.25 NaH₂PO₄, 25 NaHCO₃, 0.5 CaCl₂, 7 MgCl₂, and 20 D-glucose [35]. Rapidly dissect and section brain tissue (300-400 μm thickness) in ice-cold cutting solution to minimize excitotoxicity.

Slice Recovery: Transfer slices to artificial cerebrospinal fluid (aCSF) containing (in mM): 125 NaCl, 2.5 KCl, 25 NaHCO₃, 1.25 NaH₂PO₄, 2.5 CaCl₂, 1.3 MgCl₂, and 10 D-glucose [35]. Incubate at 32-35°C for 30 minutes, then maintain at room temperature for at least 1 hour before recording.

Intracellular Solution: Prepare potassium gluconate-based internal solution containing (in mM): 135 KCl, 0.5 EGTA, 10 HEPES, 2 Mg-ATP, 0.2 Na-GTP, and 4 Na₂-phosphocreatine (pH 7.25 with KOH, 280-290 mOsm) [35]. For synaptic current recordings, use CsCl-based solutions to block potassium channels.

Whole-Cell Establishment: Approach target neurons under visual guidance using DIC or fluorescence microscopy. Contact the cell membrane with 3-6 MΩ pipettes while applying positive pressure. Upon seal formation (>1 GΩ), compensate pipette capacitance and apply brief negative pressure or voltage pulses to rupture the membrane patch, establishing whole-cell access [34].

Recording Parameters: For current-clamp recordings of action potentials, maintain cells near their resting potential. For voltage-clamp recordings of synaptic currents, hold at -70 mV for AMPA receptor-mediated currents or +40 mV for NMDA receptor-mediated currents. Add tetrodotoxin (TTX, 1 μM) to isolate miniature postsynaptic currents [35].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Successful patch-clamp experimentation requires carefully formulated solutions and quality materials to maintain cellular health and ensure recording stability.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Patch-Clamp Electrophysiology

| Category | Component | Typical Concentration | Function and Importance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Extracellular Solutions | Artificial Cerebrospinal Fluid (aCSF) | 125 mM NaCl, 2.5 KCl, 25 NaHCO₃, 1.25 NaH₂PO₄, 2.5 CaCl₂, 1.3 MgCl₂, 10 D-glucose [35] | Maintains physiological ionic environment and osmolarity during recordings |

| Cutting Solution for Slices | 220 mM glycerol, 2.5 KCl, 0.5 CaCl₂, 7 MgCl₂, 20 D-glucose [35] | Protects cells during slice preparation; low Ca²⁺/high Mg²⁺ reduces excitotoxicity | |

| Intracellular Solutions | Potassium Gluconate-based | 126 mM K-gluconate, 4 KCl, 10 HEPES, 0.3 EGTA, 4 Mg-ATP, 0.3 GTP, 10 phosphocreatine [34] | Maintains physiological K⁺ gradient; suitable for current-clamp recordings |

| CsCl-based | 130 mM CsCl, 5 KCl, 0.5 EGTA, 10 HEPES, 2 Mg-ATP, 0.2 Na-GTP [35] | Blocks K⁺ channels; improves voltage control for synaptic current measurements | |

| Pharmacological Agents | Tetrodotoxin (TTX) | 1 μM [35] | Voltage-gated sodium channel blocker; isolates miniature synaptic events |

| DNQX and AP-5 | 10 μM DNQX, 20 μM AP-5 [35] | Glutamate receptor antagonists; blocks excitatory synaptic transmission | |

| Picrotoxin | 100 μM [35] | GABAA receptor antagonist; blocks inhibitory synaptic currents | |

| Technical Materials | Borosilicate Glass Capillaries | - | Fabrication of recording pipettes with optimal electrical and mechanical properties |

| Biocytin | 0.5% [34] | Cell filler for post-hoc morphological reconstruction of recorded neurons |

Advanced Applications and Integration with Other Techniques

Modern electrophysiology increasingly combines patch-clamp recording with other methodologies to provide multidimensional insights into neuronal function, creating powerful hybrid approaches for comprehensive investigation.

The Patch2MAP technique exemplifies this integration, combining whole-cell patch-clamp electrophysiology with epitope-preserving magnified analysis of the proteome (eMAP) for correlative functional and structural investigation [36]. This method involves filling patched neurons with biocytin during recording, followed by chemical fixation, tissue-gel hybridization, and super-resolution imaging. This enables precise correlation of physiological properties with subcellular protein expression, such as demonstrating that functional AMPA-to-NMDA receptor ratios tightly correspond to respective protein expression levels in human cortical neurons [36].

Similarly, patch-clamp recordings integrated with two-photon glutamate uncaging allow researchers to measure functional receptor properties at individual dendritic spines while subsequently quantifying protein distribution at the same synapses [36]. These advanced applications highlight how patch-clamp electrophysiology serves as a foundation for multimodal investigation of neuronal function, from molecular mechanisms to network-level processes. For drug development, these integrated approaches provide unprecedented insight into how pharmacological compounds affect not only ion channel function but also downstream signaling pathways and structural plasticity.

Automated planar patch-clamp (APC) technology represents a transformative advancement in electrophysiology, enabling direct, high-throughput interrogation of ion channel activity for drug discovery. This method addresses a critical bottleneck in neuroscience and cardiac research, where traditional manual patch-clamp techniques, while considered the gold standard for accuracy, are prohibitively slow and labor-intensive for large-scale compound screening [37] [38]. By replacing the glass micropipette with a planar substrate containing a microscopic aperture, the process of achieving a high-resistance seal (giga-seal) on a cell membrane can be automated, dramatically increasing data output and reproducibility while reducing operator-dependent variability [38]. This Application Note details the implementation of APC for drug screening, providing specific protocols and quantitative data to facilitate its adoption in research and development.

Key Principles and Technological Advantages

The core principle of planar patch-clamp involves integrating a microscopic aperture into a chip or multi-well plate. A cell suspension is added, and negative pressure draws a single cell onto the aperture, forming a high-resistance seal. Subsequent membrane rupture establishes the whole-cell configuration for electrophysiological recording [38] [39]. This fundamental design enables several key advantages over conventional methods:

- High Throughput: APC systems can simultaneously record from 384 or more cells, generating hundreds of data points in the time a manual patch-clamp experiment would yield a single recording [37] [40].

- Enhanced Reproducibility: Automation minimizes experimenter bias and variability. Assay robustness is quantifiable, with Z-factor analyses consistently showing good to excellent values, making the technique ideal for standardized screening [37].

- Direct and Quantitative Measurement: Unlike indirect fluorometric methods, APC provides direct, real-time measurement of ion channel kinetics and pharmacology with high resolution and accuracy [40] [39].

Quantitative Performance Data

The following tables summarize key performance metrics from recent applications of APC in different experimental contexts.

Table 1: Performance of APC on Native Cardiomyocytes Data derived from swine atrial and ventricular cardiomyocytes recorded on a 384-well APC system [37].

| Parameter | Atrial Cardiomyocytes | Ventricular Cardiomyocytes | Overall Performance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Patching Success Rate | ~16.1% (estimated) | ~11.7% (estimated) | 13.9 ± 1.7% |

| Seal Resistance | >100 MΩ | >100 MΩ | Stable during acquisition |

| L-type Ca²⁺ Current (I_Ca,L) Density | -4.29 ± 0.17 pA/pF | -8.65 ± 1.2 pA/pF | Comparable to manual patch-clamp |

| Pharmacology (Nifedipine EC₅₀) | 6.08 ± 1.14 nM | 3.41 ± 0.71 nM | Appropriate concentration-dependent block |

Table 2: Application of APC for Screening ENaC Modulators Data from a high-throughput screen using HEK293 cells stably expressing human αβγ-ENaC [40].

| Experimental Measure | Result / Value | Significance |

|---|---|---|

| Cell Preparation | Enzymatic detachment (TrypLE Express) | High success rate for APC recordings |

| Key Reagents | Amiloride (inhibitor), S3969 (activator), γ-inhibitory peptide | Validation of inhibitory and stimulatory effects |

| Functional Outcome | Robust, amiloride-inhibitable ENaC currents | Confirmation of reliable current measurement |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: High-Throughput Screening of L-type Calcium Channel Modulators in Native Cardiomyocytes

This protocol is adapted from studies on isolated swine cardiomyocytes and is designed for screening compounds affecting I_Ca,L [37].

I. Cell Preparation

- Cardiomyocyte Isolation: Isolate atrial and ventricular cardiomyocytes from mammalian heart tissue using a standard enzymatic digestion procedure (e.g., collagenase/protease). The expected yield is approximately 7,200-8,800 viable cells per heart.

- Cell Suspension: Resuspend the freshly isolated cells in appropriate physiological saline solution (e.g., Tyrode's solution). Keep the suspension at room temperature and use within 6-8 hours.

II. Automated Planar Patch-Clamp Recording

- System Setup: Use a 384-well fixed-well format APC platform. Prime the system with appropriate internal and external solutions.

- Internal Solution: (Example) CsCl, EGTA, HEPES, Mg-ATP to isolate Ca²⁺ currents by blocking K⁺ currents.

- External Solution: (Example) Tyrode's solution with 1.8-2.0 mM CaCl₂ to carry the I_Ca,L.

- Cell Loading: Dispense the cell suspension into the wells of the APC plate. Cells settle via gravity and suction onto the patch-clamp apertures.

- Seal Formation and Whole-Cell Access: The system automatically applies gentle negative pressure to form giga-ohm seals (>100 MΩ) and subsequently ruptures the membrane patch to establish whole-cell configuration. Monitor seal quality via capacitance and series resistance (Rseries).

III. Electrophysiology and Drug Application

- Voltage Protocol for I_Ca,L:

- Holding potential: -50 mV (to inactivate Na⁺ channels).

- Depolarizing step: A series of 200-ms steps from -40 mV to +60 mV in 10-mV increments.

- Inter-pulse interval: 5 seconds to allow for recovery from inactivation.

- Data Acquisition: Record the resulting currents. Peak I_Ca,L is typically observed at +10 mV. Analyze current density (pA/pF) by normalizing to cell capacitance.

- Drug Application:

- Establish a stable baseline recording of I_Ca,L.

- Apply increasing concentrations of the test compound (e.g., nifedipine at 1, 5, 25 nM, and 5 µM) via the automated fluidics system.

- At each concentration, re-run the voltage protocol after a set incubation period (e.g., 2-3 minutes).

- Include a positive control (e.g., 5 µM nifedipine for full block) and a vehicle control.

IV. Data Analysis

- Plot concentration-response curves by normalizing the peak I_Ca,L at each drug concentration to the baseline current.

- Fit the data with a suitable equation (e.g., Hill equation) to determine the half-maximal inhibitory concentration (IC₅₀).

Protocol 2: Identification of Epithelial Sodium Channel (ENaC) Modulators

This protocol outlines the use of APC for screening activators and inhibitors of ENaC, a key therapeutic target [40].

I. Cell Culture and Preparation

- Cell Line: Use a HEK293 cell line stably transfected with human α-, β-, and γ-ENaC subunits. Maintain cells in culture medium supplemented with selection antibiotics and 50 µM amiloride to prevent sodium overload.

- Cell Detachment: To prepare for APC, detach cells using a standard enzymatic reagent like TrypLE Express.

- Critical Recovery Step: After detachment, incubate the cell suspension in culture medium for a prolonged period (e.g., several hours) to allow for recovery from partial proteolytic activation of ENaC induced by the enzymes. This step enhances the sensitivity for detecting channel activators.

- Final Resuspension: Wash and resuspend the cells in the appropriate bath solution for recording.

II. APC Recording of ENaC Currents

- Solutions: Use symmetrical Na⁺ conditions to maximize ENaC currents. The external and internal solutions should contain a comparable high Na⁺ concentration (e.g., 135-150 mM).

- Voltage Protocol:

- A continuous voltage-ramp protocol (e.g., from -100 mV to +100 mV over 500 ms) can be used to observe the current-voltage relationship of ENaC.

- Alternatively, a holding potential of -60 or -70 mV can be maintained, and the steady-state current can be monitored.

- Validation and Screening:

- Validate the recorded current as ENaC-mediated by applying a known inhibitor, 10 µM amiloride, which should block >80% of the current.

- For screening, apply test compounds and monitor changes in the amiloride-sensitive current.

- To identify activators mimicking proteolytic cleavage, test the effect of compounds in the presence and absence of a prototypical serine protease like chymotrypsin.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Reagent Solutions for APC Experiments

| Item | Function / Application | Example & Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Stable Cell Line | Recombinant expression of target ion channel. | HEK293 cells stably expressing human αβγ-ENaC [40]. |

| Native Cells | Physiologically relevant model system. | Freshly isolated swine or rodent cardiomyocytes [37]. |

| Enzymatic Detachment Reagent | Harvesting adherent cells for suspension. | TrypLE Express; less harsh than trypsin-EDTA, improves cell health and recording success [40]. |

| Internal/External Solutions | Ionic environment for current isolation. | Cs⁺-based internal and Ca²⁺-containing external for I_Ca,L; symmetrical Na⁺ for ENaC [37] [40]. |

| Reference Agonist | Positive control for channel activation. | S3969 (small molecule ENaC activator) [40]. |

| Reference Antagonist | Positive control for channel blockade. | Nifedipine (L-type Ca²⁺ channel blocker) [37]; Amiloride (ENaC blocker) [40]. |

| Inhibitory Peptide | Tool for mechanistic studies. | γ-inhibitory peptide (Acetyl-RFSHRIPLLIF-Amide) for blocking ENaC [40]. |

Workflow and Data Analysis Visualization

The following diagram illustrates the standard workflow for a high-throughput drug screening campaign using an automated planar patch-clamp system.

Diagram 1: Automated Patch-Clamp Drug Screening Workflow.

Automated planar patch-clamp technology has firmly established itself as an indispensable tool in modern ion channel research and drug discovery. By providing high-throughput, high-quality, and reproducible electrophysiological data, it bridges the gap between molecular biology and functional phenotyping. The protocols and data outlined herein demonstrate its successful application across target classes, from cardiac ion channels to neuronal and epithelial targets, enabling the rapid identification and characterization of novel therapeutic compounds with enhanced efficiency and predictive power.

High-density microelectrode arrays (HD-MEAs) have emerged as a powerful tool for the functional characterization of electrogenic cells, enabling researchers to infer cellular phenotypes and elucidate fundamental mechanisms underlying cellular function [41]. These platforms allow for the study of cellular function across spatial and temporal scales, from subcellular compartments to entire intact networks, and from microseconds to months [41]. The technology is particularly valuable in interdisciplinary work at the intersection of biomedical engineering, computer science, and artificial intelligence (AI), finding applications in neurodevelopmental research, stem cell biology, and pharmacology [41]. For drug development professionals, HD-MEAs provide a powerful platform for assessing compound effects on neural network function in vitro, bridging the gap between traditional electrophysiology and clinical translation [42] [43].

HD-MEA Technology and Quantitative Specifications

Advances in complementary metal-oxide-semiconductor (CMOS) technology have enabled the miniaturization of electrode arrays and the integration of electronic components directly on-chip, overcoming the "connectivity problem" of traditional low-density MEAs [41]. This integration has significantly enhanced the number of electrodes, array area, spatial density, and number of readout channels while improving the signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) by avoiding long signal paths that introduce parasitic capacitance and thermal noise [41].

Table 1: Key Specifications of Advanced HD-MEA Platforms

| Parameter | Representative Specification | Application Significance |

|---|---|---|

| Array Sensing Area | 5.51 × 5.91 mm² [41] | Suitable for large networks and tissue slices |

| Total Electrodes | 236,880 [41] | High spatial sampling for detailed activity mapping |

| Electrode Density | >3000 electrodes per mm² [41] | Enables subcellular resolution and single-cell tracking |

| Simultaneous Readout Channels | 33,840 channels [41] | Massive parallel recording capability |

| Sampling Rate | Up to 70 kHz [41] | Adequate for capturing precise action potential waveforms |

| Electrode Size | 11.22 × 11.22 μm² [41] | Compatible with individual neurons and processes |

| Electrode Spacing | 0.25 μm [41] | Minimizes spatial aliasing |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Simultaneous Measurement of Field Potential and Glutamate Release

This protocol enables direct investigation of the relationship between synaptic signaling dynamics and neuronal excitation, which is particularly relevant for studying diseases like Alzheimer's, schizophrenia, and epilepsy where glutamate dysregulation occurs [44].

Key Materials:

- Enzyme-modified CNT-MEA: 64-channel indium tin oxide (ITO) microelectrode array with electroplated cup-stacked carbon nanotubes (CNTs) [44]

- Enzyme Solution: Glutamate oxidase (Glu-Ox) and osmium polymer/horseradish peroxidase (Os-HRP) with glutaraldehyde crosslinker [44]

- Preparation of Enzyme-modified CNT-MEA:

Experimental Procedure:

- Tissue Preparation: Prepare acute hippocampal brain slices (300-400 μm thickness) from experimental animals using standard procedures [44]

- System Setup: Place the enzyme-modified CNT-MEA in the recording chamber and continuously perfuse with oxygenated artificial cerebrospinal fluid (aCSF) at 32°C [44]

- Simultaneous Recording:

- Acquire field potential (FP) signals through standard MEA recording channels

- Measure electrochemical (EC) signals for glutamate detection simultaneously [44]

- Pharmacological Validation:

- Data Analysis:

- Correlate FP spike patterns with glutamate concentration changes

- Calculate glutamate release kinetics from EC signals [44]

Protocol: Functional Connectivity Analysis of Neuronal Networks

This protocol describes the use of the MEA-NAP (MEA Network Analysis Pipeline) for extracting functional connectivity and network topology from MEA recordings, applicable to both 2D cultures and 3D cerebral organoids [45] [46].

Key Materials:

- MEA-NAP Software: MATLAB-based pipeline for network analysis (open-source) [45]

- Neuronal Cultures: 2D human iPSC-derived neurons, murine cortical cultures, or 3D human cerebral organoids [45]

- Recording System: Single- or multi-well MEA systems with appropriate data export capabilities [45]

Experimental Procedure:

- Data Acquisition:

- Spike Detection:

- Functional Connectivity Mapping:

- Network Analysis:

- Pharmacological Perturbation (Optional):

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for MEA Experiments

| Item | Function/Application | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Enzyme-modified CNT-MEA | Simultaneous measurement of field potentials and neurotransmitter release [44] | Real-time monitoring of glutamate dynamics in hippocampal slices during depolarization [44] |

| Glutamate Oxidase (Glu-Ox) | Enzyme for electrochemical detection of glutamate; converts glutamate to α-ketoglutarate and H₂O₂ [44] | Key component of biosensor for measuring glutamate release in disease models [44] |

| Os-HRP Polymer | Electron mediator for enhanced electrochemical signal detection [44] | Amplification of H₂O₂ signal generated in glutamate detection assay [44] |

| MEA-NAP Software | MATLAB-based pipeline for analyzing functional connectivity and network topology [45] [46] | Tracking network development in human iPSC-derived cultures and identifying hub nodes [45] |

| Human iPSC-Derived Neurons | Physiologically relevant human cellular models for disease modeling and drug screening [45] | Studying neurodevelopmental disorders and screening therapeutic compounds [45] |

| Cerebral Organoids | 3D human stem cell-derived models that recapitulate aspects of brain development [45] | Investigating network formation in complex 3D environments modeling human brain development [45] |

Data Analysis and Interpretation

Quantitative Analysis of MEA Data

Table 3: Quantitative Analysis Methods for MEA Data

| Analysis Type | Appropriate Quantitative Methods | Biological Interpretation |

|---|---|---|

| Univariate Analysis | Descriptive statistics (mean, median, standard deviation of firing rates, burst parameters) [47] | Basic assessment of network activity levels and excitability [45] |

| Functional Connectivity | Spike Time Tiling Coefficient (STTC), probabilistic thresholding for significant connections [45] | Mapping of information flow pathways and functional interactions between neurons [45] |

| Network Topology | Graph theory metrics (modularity, clustering coefficient, path length, efficiency) [45] | Assessment of network organization, efficiency of information transfer, and resilience [45] |

| Node Cartography | Classification of nodes based on connectivity patterns (hubs, peripherals, connectors) [45] | Identification of critical elements that control network stability and information integration [45] |

| Dimensionality Reduction | PCA, t-SNE, UMAP for visualizing network developmental trajectories [45] | Tracking network maturation and classifying network states across development or treatment [45] |

Integration with Other Modalities

The combination of HD-MEAs with other experimental techniques enables multimodal investigation of cellular function, providing more comprehensive biological insights [41]. Recent innovations have focused on adding other readout modalities to HD-MEAs and introducing innovative electrode designs for intracellular-like measurements at scale [41]. These integrated approaches are particularly valuable for translational applications, including functional phenotyping of human cellular models and drug screening, where they provide insights often inaccessible through single-method characterization techniques [41].